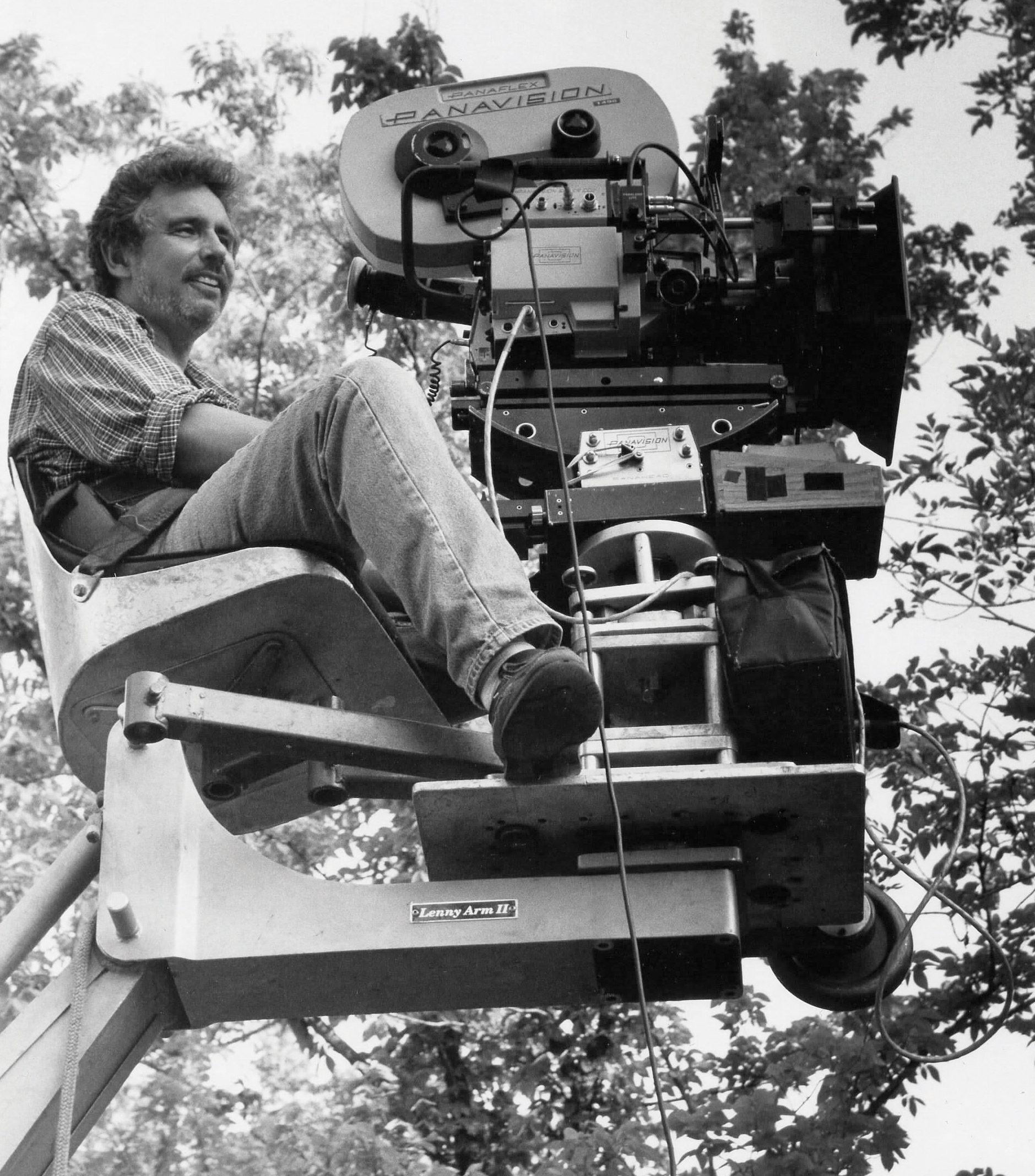

Fred Murphy, ASC: Daring to Be Bold

The ASC Career Achievement in Television Award honoree brought an experienced eye to the medium, delivering a dramatic vision.

The career path of Fred Murphy, ASC has not been clear-cut, emerging naturally from multiple interests: photography, architecture, animation, the ocean, editing, lighting, and, of course, movies. Many of these pursuits remain, but he ultimately defined himself as a cinematographer — one who has created a distinctive body of work spanning nearly every genre in film and television. Upon accepting the 2023 ASC Career Achievement in Television Award, presented during the 37th Annual ASC Awards on March 5, he remarked, “It came as quite a surprise. I’m really touched to be honored like this.”

Murphy was born into a family of longtime New Yorkers. “We’ve been here since the early 19th century,” he says. “I live about five blocks from where my great-grandfather lived during the Civil War.” He picked up an interest in photography at Holy Cross High School in Flushing, binged second-run movies at a theater in the East Village, and later studied architecture at the Rhode Island School of Design. “That’s where I made my first film,” he recalls. “I was supposed to build a model with a bunch of moving parts, but I was a terrible modelmaker, so I borrowed my brother’s 16mm movie camera, read the manual, and made a one-roll cut-out animated film. It went over pretty well.”

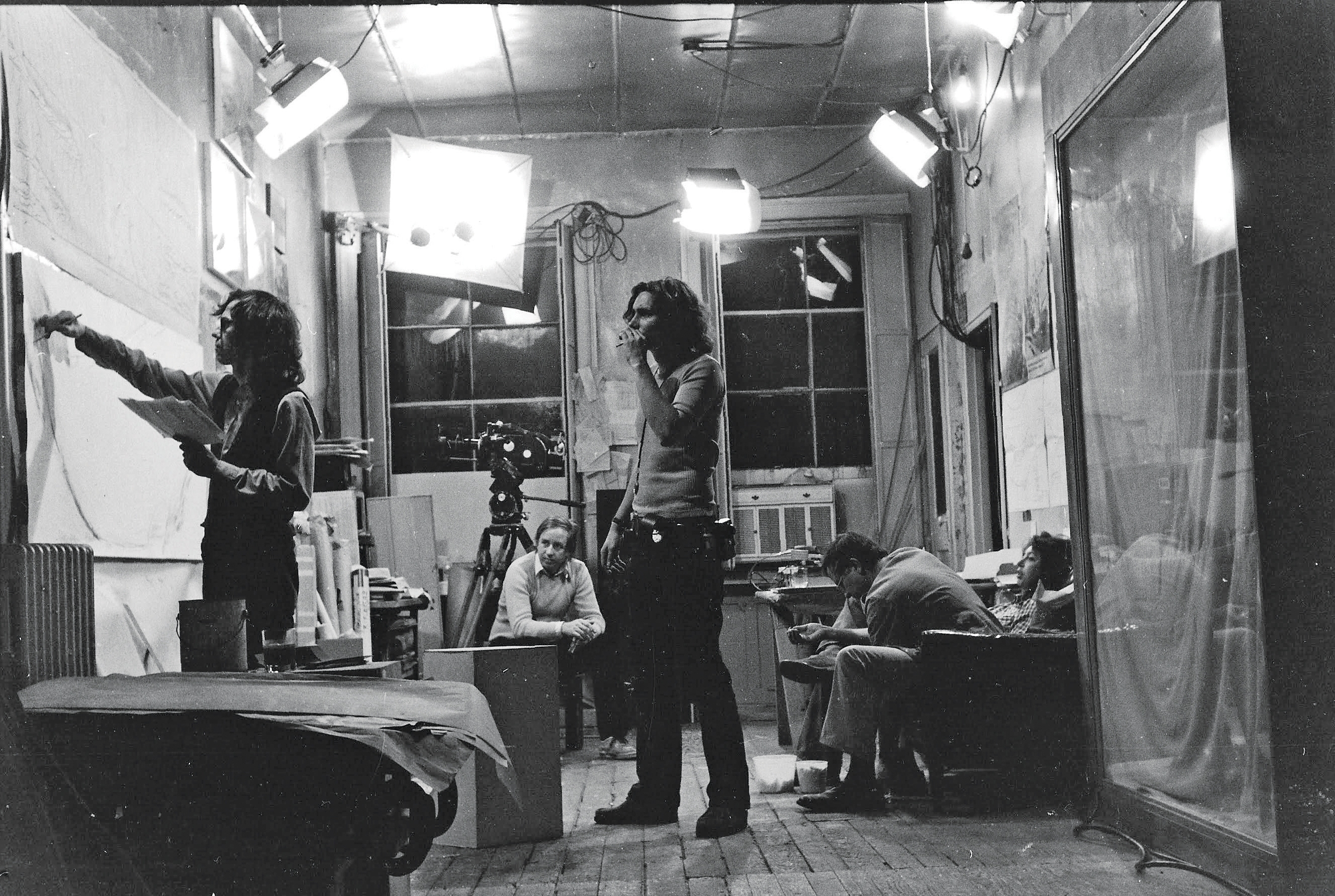

Energized by the experience, Murphy left RISD to find work in the film industry, and soon found himself aboard a research vessel in the Pacific, shooting photos of the ocean floor. Back in New York City, he worked as a runner for a post-production house, and was later fired from an opticals company for not cutting his hair. (“It was that time in history,” he says.) After buying a Bolex 16mm camera, he shot short, personal documentaries about jazz composer Sun Ra and New York tattoo parlors. Upgrading to an Éclair NPR, he shot more documentaries and news footage for local and foreign television stations in New York City. While struggling to support himself, he drove a truck for large commercials and industrial film productions — and then started working as an electrician and lighting them.

Around that same time, in the mid-to-late ’70s, his film career started taking off with independent 16mm projects directed by fellow RISD alum Martha Coolidge (Not a Pretty Picture), Mark Rappaport (The Scenic Route) and Claudia Weill (Girlfriends). Weill’s then-partner Richard Pearce later hired Murphy to shoot the PBS TV movie The Gardener’s Son (based on the Cormac McCarthy novel), and then the 35mm feature Heartland, which won the Golden Bear at the Berlin International Film Festival in 1980. “That changed my perception of what I could accomplish,” says Murphy, who signed with agent David Gersh and was soon shooting two to four features a year.

Mentors and Manhattan Mayhem

In 1982, Murphy took a job operating for renowned cinematographer Henri Alekan on Wim Wenders’ The State of Things. Alekan taught Murphy when and how to do an iris pull, how to correctly filter black-and-white film for greater contrast, and how to be bold with color. “Henri was probably the only real mentor I ever had,” Murphy says. The French master also shared cinematography screen credit with Murphy on the feature (along with Martin Schäfer).

That same year, genre king Larry Cohen came calling with Q: The Winged Serpent, in which the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl makes a nest in the spire of the Chrysler Building and terrorizes Manhattan. The production made movie history when an unpermitted stunt — involving the real Chrysler Building and construction workers in SWAT costumes, firing blanks from real automatic weapons over midtown on a weekday afternoon while Murphy and Cohen filmed from a circling helicopter — made the front page of the New York Post.

Finding His Voice

The 1980s brought numerous collaborations with a variety of directors, resulting in films like The Trip to Bountiful (Peter Masterson); Hoosiers (David Anspaugh); The Dead (John Huston); and Enemies, A Love Story (Paul Mazursky), through which Murphy began to find his voice as a cinematographer. “You get better with time,” he says. “I learned a lot of things from John Flynn — the director of Touched and Best Seller — mostly about how to make shots more dramatic, how to up the excitement level, and how to be succinct.”

Throughout the 1990s, Murphy honed an artistic yet natural approach to lighting that was well-suited for such dramas as Jack the Bear (Marshall Herskovitz) and Murder in the First (Marc Rocco) and could be tailored to serve any story, from the Hollywood action comedy Metro (Thomas Carter) to the psychological horror Stir of Echoes (David Koepp). In the 2000s, he entered a stylish and distinctive period with the slasher film Freddy vs. Jason (Ronny Yu), the horror mystery The Mothman Prophecies (Mark Pellington), and the period crime drama Auto Focus (Paul Schrader).

Breaking Out in Television

In 2007, Murphy was delayed while timing a feature print in Los Angeles when he received a call to fill in on the first season of HBO’s In Treatment, starring Gabriel Byrne. “I’d shot several TV movies, but I didn’t really think of myself as a television person until I started shooting a television series,” he reflects.

Though Murphy considers In Treatment’s format as “basic, often just two characters talking,” he only had two days to complete each episode. “But on a TV series, it’s not like you’re starting from scratch every day, and that makes a big difference.” In Treatment was his first experience working with a digital camera — the Sony CineAlta F950 — and he received an Emmy nomination for his very first episode.

Murphy’s next major television offer came through gaffer and regular collaborator Tim Guinness, who was in New York working on Fringe, a Fox series about an FBI agent who teams up with an institutionalized scientist and his troubled son to solve mysteries related to a parallel universe. “Brooke Kennedy was co-executive producing it, and she wanted it to look like a movie,” says Murphy, who shot five episodes of the first season, trading off with Thomas Yatsko, ASC and Michael Slovis, ASC. “The New York part of the first season was on another level. We shot on film with all the means you’d possibly want. It was like a movie.

It wasn’t just a creative approach to photography that made the results more cinematic, Murphy points out. “Television taught me how to do it better, faster — but when I started on Fringe, I made an effort to not worry about ‘getting it done.’ I’ve got a good gaffer, a good key grip. I’ll rely on them to keep me moving, but I’m more interested in what the show is going to look like.”

The Kings’ Man

After Fringe moved production to Canada, Kennedy asked Murphy to shoot the first season of The Good Wife for showrunners Michelle and Robert King, in which Alicia Florrick (Julianna Margulies), the wife of a disgraced Illinois politician, returns to her law career. (M. David Mullen, ASC shot the pilot.)

The Good Wife was shot in New York, first with Sony’s CineAlta F35, then with the Arri Alexa. Murphy describes the look of the show as “elegant, like a movie where everybody looks as good as possible. I always encouraged the operators to use more dramatic angles: high angles, low angles, and wide angles. We tried to make better use of the foreground. Don’t center-compose the actors unless it’s called for.” During production, he’d whisper references to The Maltese Falcon and The Night of the Hunter to his operators over a wireless headset. “Night of the Hunter was Robert’s idea — the way those sets look, the darkness, the abstractness,” Murphy elaborates. “Beyond that, he allowed me to do whatever I wanted — however dark I wanted to make it, whatever colors I wanted to use.”

He found strong allies in the Kings, who supported his vision for their show. When Murphy wanted to do away with protecting the 1.33:1 frame within their 1.78:1 aspect ratio, they petitioned CBS’ then-chairman Les Moonves. Murphy’s choice was vindicated when an episode from Season 2, the first season that took advantage of the full 1.78:1 frame, earned an Emmy nomination for Outstanding Cinematography for a Single-Camera Series. After The Good Wife’s second season, Murphy started using a 2.1:1 frame, then, two years later, expanded it to 2.39:1.

Murphy followed this format of breaking old TV habits for seven successful seasons — shooting more than 100 episodes and earning another Emmy nomination — before moving on to a new series for the Kings in 2016: BrainDead, a science-fiction political satire set in Washington, D.C., about a government employee who discovers that the cause of the tensions between America’s two major political parties is a race of extraterrestrial insects eating politicians’ brains.

Murphy calls BrainDead one of his favorite shows because he was given the opportunity to challenge conventional notions of what a television show could look like. “It’s different from The Good Wife, veering into genre. We used wide lenses and low camera angles. We took risks.

Murphy’s work on The Good Fight — a more humorous but no less elegant spin-off of The Good Wife, starring Christine Baranski — started in 2017. He shot five episodes of the first season, including the pilot, before shifting his focus to another of the Kings’ projects, a new series for Paramount Plus entitled Evil, about a skeptical clinical psychologist who joins a priest-in-training and a blue-collar contractor to investigate abnormal events and extraordinary occurrences.

“Evil offered me the chance to do something with a darker, more contrasty look,” says Murphy. “The visual aspect plays a strong role in the show. Our color palette comes from 14th-century Italian painters. And since the show is somewhat about the Catholic Church, it made sense to start pulling out books on Giotto. It’s part of the mix of writing, acting, and art direction that gives the show its heart and makes it good.”

That The Good Fight and Evil are streaming series may account for the artistic freedoms allowed to risk-taking creators, Murphy posits. “Streaming raised the bar for everything in television, especially design. DPs have bigger budgets. Producers pay attention to how a show’s visuals tell the story. And with all the technological improvements in cameras and lighting, plus high-resolution displays at home, we simply have a better canvas.”

Connected to the Past

Murphy was bestowed with the Society’s career honor during the 37th Annual ASC Outstanding Achievement Awards, held on March 5. In one of the most heartfelt moments of the night, presenter Jake Gyllenhaal discussed the meaning of collaboration and friendship while recalling his experience working with Murphy as a young actor on his first feature film, the 1999 period drama October Sky.

In director Joe Johnston’s biographical drama, based on the life of NASA engineer Homer H. Hickam Jr., Gyllenhaal plays a youth obsessed with science and rocketry. “I’m in pretty much every scene,” the actor described. “And even though I’d dreamed of the moment for as long as I can remember, I was scared out of my mind. So, there I am, in Knoxville, Tenn., on set, surrounded by a crew of 100 people. I had this scene with a ton of science jargon, and I had it in my mind that I had to deliver it all in one breath, in one take. That I can’t make a mistake. I look up and see Fred Murphy standing over me, smiling. He can see I’m petrified, and he says with his uniquely beautiful mix of New York swagger and mad scientist: ‘You’re okay to make some mistakes. I got you.’ As if to say, there’s plenty of space in my frame for the imperfect. Nobody is interested in the perfect, anyway.”

Handing Murphy his award, Gyllenhaal’s smile was that of an old friend, and the cinematographer was clearly touched. He noted in his acceptance speech, “One of the beautiful things about being a cinematographer is all the people you collaborate with — directors, designers, actors, gaffers, grips, operators, assistants. Some become lifelong friends, others wonderful collaborators.

“The thing I love about the ASC, besides friendships and events, is it puts me in touch with the history of cinematography and motion pictures. I feel it connects me to the past and to all the movies I watched growing up, and the people who photographed them. Just being in the ASC Clubhouse makes me think of Gregg Toland, Lee Garmes, James Wong Howe, Vilmos Zsigmond, Haskell Wexler and Conrad Hall. It is an honor to be in their company. Thank you, ASC, for this great honor.”

You can watch the entire 37th Annual ASC Awards here, including Murphy's presentation.