Full Metal Jacket: Cynic’s Choice

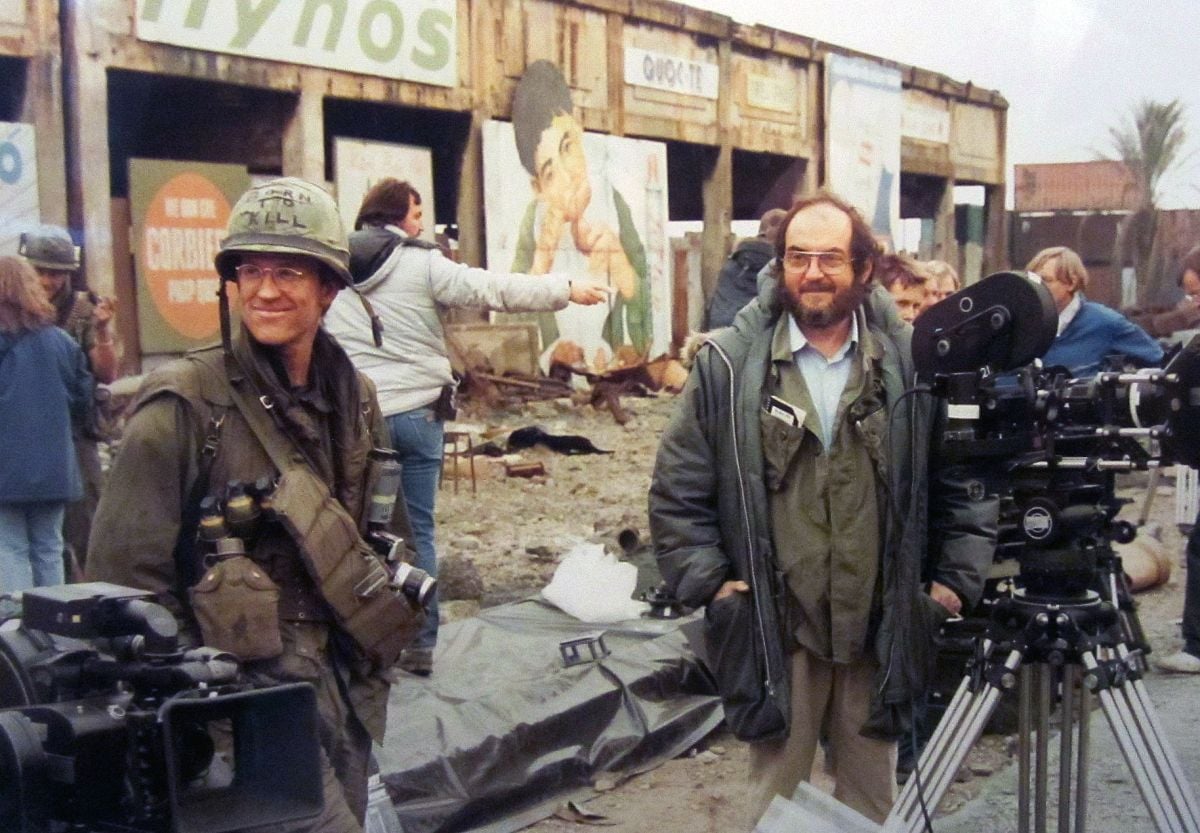

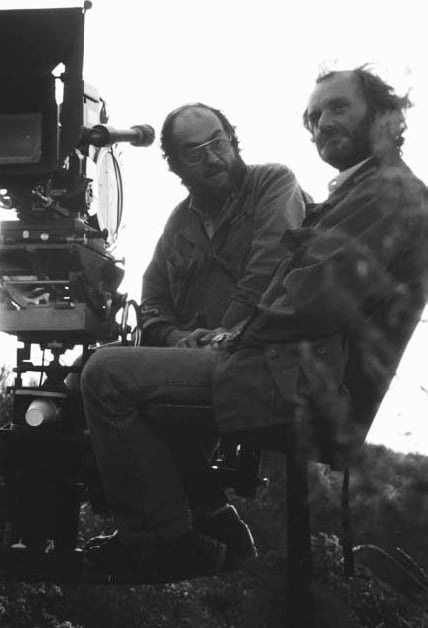

Cinematographer Douglas Milsome, ASC discusses his close collaboration with Stanley Kubrick on this harrowing and bleak Vietnam War-set drama.

It has been exactly 30 years since Stanley Kubrick’s first “war movie,” Paths Of Glory, laid the foundation for his undisputed status as a world class filmmaker. The film is at times naively ideological but full of power and passion in its belief that the common man is merely a pawn in the game of war.

Now, on the 30th anniversary of Paths Of Glory, Kubrick has presented us with what is arguably his most cynically despairing, grim and disturbing film ever: Full Metal Jacket. The common man may still be a pawn of the government’s war machine, but this time around the price of obedience isn’t his life — although that may become forfeit — but his humanity. The title refers to a type of bullet commonly used in the Vietnam War, but it might also reflect the icy documentary-like detachment that characterizes the film’s sardonic tone.

Kubrick is definitely a team player, so it comes as no surprise that the man he chose to shoot Full Metal Jacket, Douglas Milsome [ASC], has been a participant on every one of his films beginning with A Clockwork Orange, where he served as the late John Alcott [BSC]’s focus puller. Milsome quickly moved up through the ranks, becoming Alcott’s first assistant on The Shining. lt was on this film that he was allowed to shoot some first-unit footage after Alcott left to work on another project. On his own after 15 years with Alcott, Milsome has proved himself a worthy successor to his great mentor, whose style and meticulous attention to detail he tries to emulate. “I’d like to carry on where John stopped, actually,” he says. “I thought he was a great photographer and I learned a lot from him working with Stanley. I use the Alcott System all the time now. He taught me how to use black-and-white Polaroids to measure a great deal more than just exposure — it gives you the balance and allows you to go much higher or lower than the meter would otherwise indicate against film speed. The Polaroid film delineates very well between light and shade, and also gives a tremendously good idea of how windows are going to look if they’re over- or-underlit. The passing of John was such a blow to me that I’ve determined to try to perpetuate what he was trying to do. He lit like no other cameraman, so effectively with little or no light. Most of his lighting went into one suitcase, and that’s what I like and it’s what Stanley likes, too.”

Although Kubrick’s films take notoriously long to shoot, nothing is left to chance and much of that time is spent in pre-production with the cinematographer. “Although I was actually on the film for a year and a half,” Milsome points out, “the shooting actually took a lot less time than people believe. The actual shooting took just over six months and we had to shut down for some 20-plus weeks due to injuries and accidents. My period of pre-production, however, was considerably longer than most. There’s always an awful lot to discuss with Stanley during pre-production because there’s so much involved with his films. They’re always big subjects, so the cinematographer is often brought in quite a bit earlier than usual, not just to check the equipment but to check every single aspect of every possible situation to the n-th degree. It involves painstaking time for discussion. He’s just as methodical in his prep as he is in his shooting. Sometimes his prep takes as long as his shooting, often longer. He gives a new meaning to the word ‘meticulous’ and the word ‘methodical’. As far as the lighting is concerned, that’s open to discussion. We build models of our sets and discuss how to light them and then we do extensive testing.”

“I’ve actually had a lot harder time working for a lot less talented people than Stanley. He’s a drain because he saps you dry, but he works damn hard himself and expects everybody else to.”

— Douglas Milsome

Nearly all of the equipment used by Milsome on Full Metal Jacket was owned by Kubrick, who maintains stores of the most up-to-date and advanced equipment available. For many of the large tracking shots that comprise much of the film’s action footage, a variety of cranes and Steadicam were employed. Primarily, Milsome used the Arri BL camera and Zeiss high-speed lenses. For some extreme slow-motion effects, Kubrick purchased two of Doug Fries’ high-speed cameras adapted from standard Mitchells, which were used in combination with numerous Nikon lenses.

From its inception, Kubrick and Milsome agreed that Full Metal Jacket should have the desaturated, grainy look of a documentary. “We did that by using the high-speed Kodak 5294, which we rated at 800 ASA all the way through,” Milsome recalls. “It should’ve been 400, so we were pushing it a little beyond where it would’ve given us a really solid black. By pushing the film all the way, we were able to bring the fog level up, and there was a natural lean toward the milkier, less solid blacks and grays, which documentary film tends to have. The film helped us a lot in achieving that look, coupled with the fact that we were working wide open. Even on days where it was fairly hazy but sunny, we used a lot of neutral density filters on the camera purely as a means of reducing the light transmission through the lens, which took some of the contrast out of the image and flattened it a little more. Also, we shot without an 85 correction filter for daylight, which gave us an extra percent of a stop in hand. We pulled the blue out to make it look less cold, but we were able to correct for this color shift on the set. It just enabled us to get that little extra half hour or hour’s shooting at the end of the day.”

That extra bit of time can be crucial. Though Kubrick’s films have lengthy schedules, it isn’t because he tends to work at a leisurely pace. Kubrick’s demanding perfectionism is both a strain and an extremely rewarding attitude for those used to working with directors who expect less, Milsome explains: “I’ve actually had a lot harder time working for a lot less talented people than Stanley. He’s a drain because he saps you dry, but he works damn hard himself and expects everybody else to. Sometimes it becomes a plod because it’s so slow and intricate, but he loves to do things quite differently than what has ever been done before. You can’t really do that sort of thing off the top of your head, so you work very hard to get it together and make something different which bears his mark. That can be a little overbearing and it tends to zap you and take up nearly all of your time. Sometimes the relationship can get a little strained because you’ve got to be devoted to him. You eat, drink and sleep the movie, and you’re under contract to Stanley body and soul. But he allows you the time to get everything absolutely right, which is what I find so rewarding.”

“There were occasions on Full Metal Jacket where we went a few more than 25 or 30 takes, but we usually didn’t average more than 10 to 15 takes, although sometimes we’d go back and reshoot certain scenes later.”

It is this insistence on achieving perfection regardless of how many takes are necessary for which Kubrick is most infamous. “Stanley always has done many, many takes” Milsome says, “but in fact, the many takes are not just repetitions of the same thing, they are often building upon a theme or idea that can mature and develop into something quite extraordinary. The whole structure of the scene can actually change during the operation of filming it. Also, Stanley gets a lot more out of his actors after he works with them a lot longer. It’s especially valuable in bringing out something in actors who may not be exactly up to the part, but Stanley works on them jolly hard until they produce the goods. That’s why he’s so good with actors: in the end, he’ll rehearse and rehearse them until they’re word perfect, and when they’ve got the words perfect then the rest has to happen — they then have to act. The large number of takes are used mainly to get something out of the actors that they’re not willing to provide right away. Of course, it’s demanding on the crew as well, but it’s a lot harder for the actors than it is for us. Once you’ve done an eight- or ten-minute scene a number of times, after take 30 or 35, you’re really into it!” Milsome laughs. “Actually, it doesn’t always go that many takes. There were occasions on Full Metal Jacket where we went a few more than 25 or 30 takes, but we usually didn’t average more than 10 to 15 takes, although sometimes we’d go back and reshoot certain scenes later.”

Full Metal Jacket was shot entirely in England on sets ranging from a meticulously reconstructed Marine Corps barracks to a blasted building that served as the background to the Tet Offensive at the end of the film.

The two-part structure of the film necessitated recreating the Marine training camp at Parris Island in great detail for the basic training of the “grunts” that comprises the film’s grueling first half, while the second half of the film had to look like Vietnam location footage. Surprisingly, Kubrick found the ideal location for both sets in three different locations in the Northeast London area, not more than 30 miles apart. Parris Island’s training camp was a real military base in Bassingbourne, the barracks were built at Enfield, and the vast rubble and blasted buildings of the Tet Offensive were to be found in an East London gasworks.

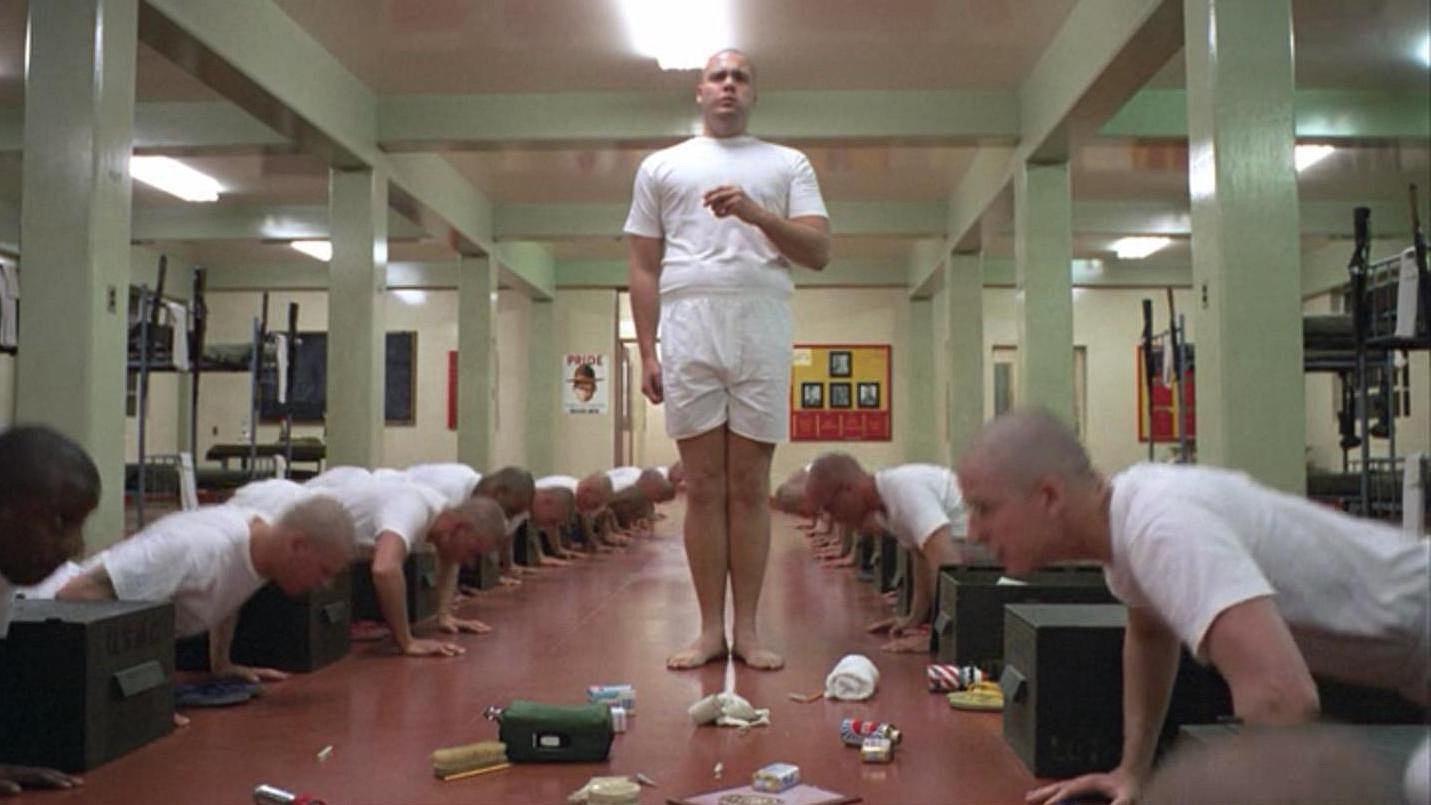

The film opens inside the practical barracks set Kubrick had constructed at Enfield, as Milsome’s camera dollies along with Gunnery Sgt. Hartman, played by R. Lee Ermey, as he indoctrinates the new recruits into the harsh, contradictory realities of Marine life. Ermey, who is not an actor — he was actually the film’s technical advisor and a real-life drill instructor — went through the sequence again and again, as Kubrick coached him on the precise inflections and mannerisms he wanted. All told, there were 25 takes or so the first time around. Ermey suffered injury in a car accident during shooting, after which “he’d improved no end as an actor,” Milsome relates. “I think he polished up his part quite well, so we did that particular scene all again. It was well worth it because he was so much better.”

In order to accommodate Kubrick’s proposed 360-degree shooting approach. Milsome had to place all of his lighting outside the set, where it streamed in like cold sunlight through the large windows on either side of the barracks. Milsome had become accustomed to the director’s need for total freedom on the set, and so emulated Alcott’s daytime interior look for the palaces of Barry Lyndon and the lobby of The Shining’s Overlook Hotel.

“You can’t restrict anything Stanley wants to do by having a light source which shouldn’t be in the shot in the way,” Milsome confirms. “Stanley likes the total freedom of being able to go anywhere at any time, so we reproduced the look of sunlight streaming through the windows. The lighting was all totally outside — there were no lamps inside anywhere except for the warm-white deluxe daylight flourescent tubes in the overhead strips which were featured as a source light anyhow. So we just let the sunlight bleed in through the windows, which gave us a very natural single-source light with a very soft fill, roughly about 3:1 on the shadow side. For this effect, we used the Par 600-watt lamps — each light has six 100-watt bulbs on it. We put four of these lamps outside each of the seven window’s in the set, so we had 24,000 watts burning outside each window. We had them filtered through the Rosco plastic 216 fibre, which gave us a very nice, soft, warm look.

“We used a very old Moviola dolly with pneumatic tires which we let down so they had only a minimal amount of air in them. Although the floor of the barracks set wasn’t that smooth, we were able to wheel the dolly about the floor because the fairly flat tires actually made the shot very smooth.

“The Louma crane was a great tool to us,” Milsome says. “We did a lot of low-angle tracking shots that ended with the camera soaring up into the sky as the troops were drilled. We had a remote hot head rig we could operate from below so we didn’t have to actually sit on the crane. We also mounted our camera on a Tulip crane with a Skycam extension, so we could get our lens over 30 feet up. We were able to use both types of crane rigs to create some really interesting camera moves that enhanced the training sequences. With this equipment, when they went over the obstacle course, we could go up with them, so there were quite a lot of shots of them climbing ropes and over barriers and things where we just followed them up.

“Because we were using the Louma crane quite often, we decided to have the crane ready assembled on a track always,” Milsome continues. “Although the crane itself is not that heavy — about 1,000 pounds — it does take some hours to put together. We got a 60-seat coach, left the cab as it was, sawed the coachwork off and made the rear end into a 30-foot-long tracking platform on which we laid our rails. Our crane was always completely assembled on this tracking coach, so we could drive it into any position within minutes, secure it with hydraulic jacks and be ready to do our shot very quickly”

The climax of the film’s boot camp segment is carefully orchestrated in two powerful and disturbing nighttime scenes in the barracks, where the harsh blue moonlight filtering in through the windows is in sharp contrast to Milsome’s warm pink daylight look.

The first sequence consists of the ritual beating of Gomer Pyle — played by Vincent D’Onofrio — by his fellow recruits after they are forced to do push-ups when Hartman discovers a donut in the overweight private’s trunk. The sequence is eerie and frightening, and Pyle’s pain and horror are well served by Milsome’s objective photography and stylized lighting.

“We wanted to introduce a strong moonlight effect, which I think worked and gave a weird feeling to it all. It’s similar to the blue light we used in the maze in The Shining. For this scene, we used an open Fresnel Brute, which gave us very sharp shadows, and four 10K HMIs, white flame, without condensers, so they also cast very long and definite shadows. The Brute was placed at one end, giving a much wider, brighter beam, and the other four windows were each lit by one of the 10K HMIs. We then put half blues over them to give us a kind of Hollywood moonlight glow. Again, all of our light came from outside, and we used polystyrene to bounce the light or we bounced light from a 1000-watt snooted Lowell off the ceiling just to reflect a little bit of white light into the shadow side. We had a key of F.2, so we probably had about .70 on the shadow side, which meant we were working at roughly a 4:1 ratio.”

That same combination of naturalism and stylization pays off handsomely in the gruesome climax of the film’s first half, wherein Pyle goes quietly mad after becoming a full-fledged Marine killing machine. Eyes rolled back into his skull and glowing with a strange inner light, he turns his M14 rifle — with its full-metal-jacket shells — first on an outraged Hartman and then on himself.

“D’Onofrio flashes what people are now referring to as the ‘Kubrick crazy stare.’ Stanley has a stare like that which is very penetrating and frightens the hell out of you sometimes — I gather he’s able to inject that into his actors as well.”

“That scene was very powerful,” Milsome agrees. “D’Onofrio flashes what people are now referring to as the ‘Kubrick crazy stare.’ Stanley has a stare like that which is very penetrating and frightens the hell out of you sometimes — I gather he’s able to inject that into his actors as well. The light in D’Onofrio’s eyes was achieved quite naturally: The bathroom was tiled out quite white, so there was a massive amount of light coming back off | them onto his face, which helped.

“Again, the lighting was fairly straightforward. We had the same configuration as in the barracks, except with 5Ks in this case, placed four flights up shooting down through the bathroom window and throwing patterns on the wall, and we introduced the blue element again. The action part of the sequence didn’t take as much time as getting a performance. The pattern of Pyle’s brain on the wall after he shoots himself didn’t take all that long to get right, and for Hartman’s death, Lee Ermey just shot straight back — I think he’s been hit before, because he bounced back well!’

Fade to black. When the lights come back on, we’re on a city street somewhere in Vietnam, following close on the heels of a Vietnamese prostitute as she propositions a couple of our Marines — Joker and Rafterman, played by Matthew Modine and Kevyn Major Howard. This shot typifies the style of the remainder of the film, as Milsome’s roving camera prowls through one vast urban landscape after another. “We used the Louma crane to a large extent on our exteriors,” Milsome says. “We had no exterior light apart from daylight and we used that right up until the 11th hour. There was no day-for-night at all. We shot night-for-night lit by these Wendy lights, which each hold about 200 bulbs. When hoisted up over 100 feet on a cherry picker, they can light an enormous area from over two hundred yards away. They each took about 1200 amps, and we could actually light an area of 400 square yards quite easily at a light level of T1.4.”

Milsome also made use of a rather unusual dolly for many of the battle sequences: a camera car with its engine removed. “Stanley bought a Citreon Mahari, which proved to be quite useful,” he recalls. “It’s a very good, soft suspended tracking car, on which we mounted two cameras. We ripped the engine out of this one and pushed it along — it was fairly easy to push — and we did a lot of our tracking shots with that. We used it on Barry Lyndon to do many of our tracking shots across fields. It worked much better than a dolly because, tracking that fast, a dolly would have meant an unsteady picture, and I don’t think a Chapman crane could’ve tracked that fast with stability on a non-metallic surface. The car had an extremely soft ride and we were able to push it quite fast. We often had about six people pushing, one steering and three or four camera operators.”

The Tet Offensive, which compromises the primary focus of Full Metal Jacket’s grim second half, began quite treacherously at dusk on a Vietnamese holiday, during which time both sides had agreed there would be no fighting. Kubrick decided to stage the first wave of the offensive outside an American army base, where soldiers are holed up behind sandbags in flimsy tents. This set, called “the hooches,” was built at Bassingbourne, across from the camp that doubled as Parris Island. Milsome remembers the inherent difficulties in photographing huge scale special effects for this sequence: “Choreographing our camera movement was extremely important, otherwise we’d waste a lot of money on effects we wouldn’t catch on film if we’d missed our mark. It became a question of rehearsing a number of times to insure we got it right.”

The lighting source for the night-for-night sequence were four Wendy lights posted in different corners of the training camp, which greatly facilitated quick changes from one angle to another. “If we wanted to change the direction in which we were shooting,” Milsome explains, “we’d just save one lamp and switch another one on so we always had a moonlit backlight source illuminating the scene. Once the Wendy lights are in position, they’re a hell of a job to maneuver, especially on soft ground, so having four saved us a great deal of time we would have spent moving them about, which enabled us to get our night work done that much faster. The lamps, from over 250 yards away, were able to give us a fast 1.4 backlight on the 94 Kodak film. We’d shoot at F.2, which was about one stop under. It was quite enough, and the rest of our light we would fill using sheets of styrene. We black velveted the actual trucks and the jib arms the lights were on so you couldn’t see them if we panned across them.”

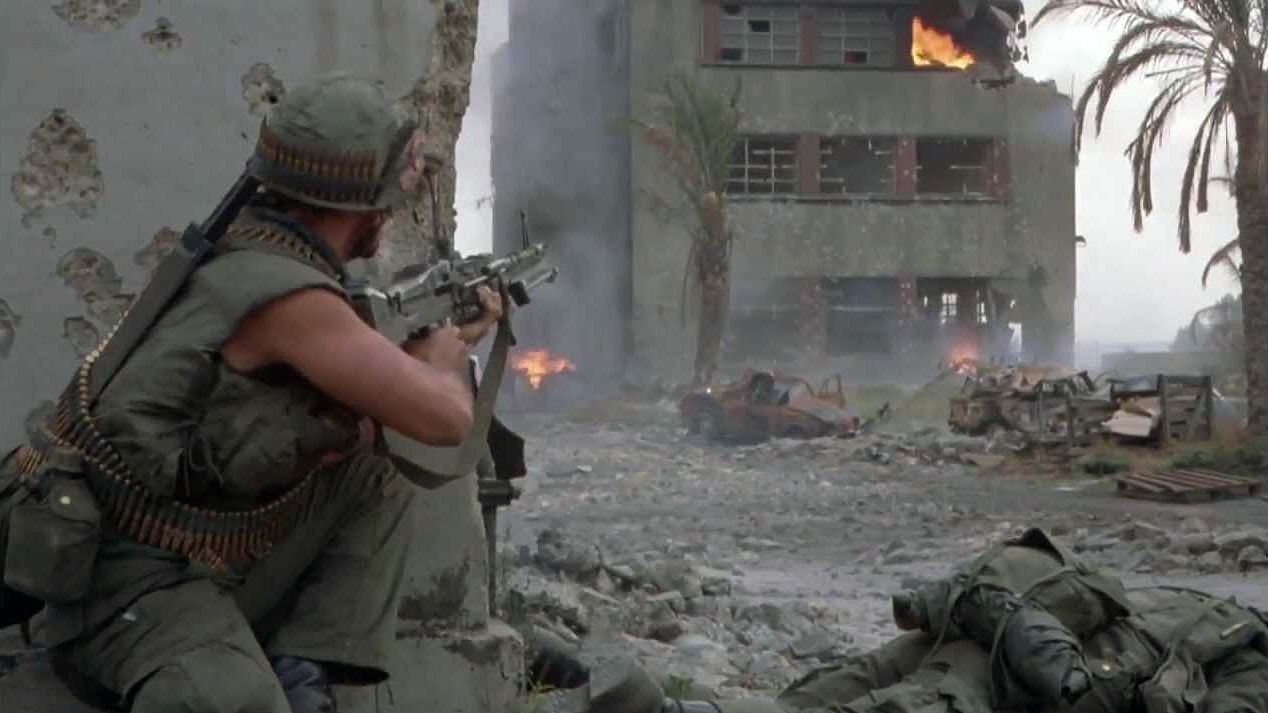

The last 20 minutes of Full Metal Jacket comprise Private Joker’s “dark night of the soul,” as he and Rafterman are caught in an ambush along with the platoon they’ve been assigned to cover as combat journalists. The platoon leader has been killed, so leadership now falls to one of Joker’s fellow Marines from boot camp, Cowboy (Arliss Howard), who is ill-suited to the task of negotiating his way out of the deadly situation. The tension is evident as the recruits huddle in fear behind a blasted wall as buildings blaze hellishly around them.

“The final ambush sequence was shot over several afternoons around the low end of the day, when the exposure wedge was dropping away,” Milsome recalls. “It was a good time to do that because we were wide open so we got the maximum effect from the flames. If you underexpose them, you don’t get the maximum effect. This way, the flame looked so much brighter and had a glowing quality, which was helped by the fact that they were all shot around magic hour-dusk time. We carried on with our shooting from late afternoon as it turned into evening, before it actually became night, for days. We were working with fast film and fast lenses at 1.4 going way down until the exposure level just went.

“Although we had exposure from the sky,” he continues, “we still needed to throw some light on the actors’ faces. We mainly did that using kicker lights that glanced off their heads or gave us a ¾ backlight. We primarily used Lowells or Redheads from quite a distance away, spotted up so they had a very directional beam that wouldn’t spill anywhere else. We introduced flame red into the color of the lights too, to give them a warm glow.”

Interestingly, the scene of the troops awaiting Cowboy’s decision is as formally framed as Kubrick’s handheld-style battle footage that follows, which Milsome finds remarkable: “Stanley’s composition is very stylized. The way he places people is just amazing. You’ll never find a Kubrick setup where the actors’ feet are cut off. Every shot is either from the waist up or full-length. Every one of his movies has that look; very square, very level and symmetrical. Things are placed exactly right every time. I use that style a lot even when I’m not working with him because that’s the sort of thing that I like myself. The use of extreme wide-angle lenses is distinctive, too, and allows us a great area in which to manipulate the action. We used a lot of wide angles to compose interesting shots, as well as a lot of very close angles on the same shots, and then Stanley would cut from one extreme to the other.”

For the intensely visceral battle sequence that ensues, in which members of the platoon are mercilessly, repeatedly wounded by a hidden Vietnamese sniper in a largely successful attempt to draw the other members of the company out into the open, Milsome employed a great deal of Steadicam shots following the Americans across the battlezone. For the bloody closeups of the massacre itself, in which Marines are literally blown to pieces, Kubrick utilized exteme slow motion to emphasize the pain and the horror.

“We had two high-speed Fries cameras going at five times speed [120 fps] as the soldiers were shot,” Milsome remembers. “We just tore them open with lots of squibs and ran our cameras at very high speed. We used Nikon lenses to a very large extent in this sequence, not only for their extremely sharp definition and clarity, but for their many varying focal lengths. The range of the focal lengths go from 5mm every mil up to 100 or 200mm. The long-focus lenses go up to 1200mm, which we could double and make 2400mm. They’re slow, but with the fast stock, we still had the aperture we needed on location without losing any of the quality — they don’t look like regular telephoto lenses. I think they have the supreme edge for optimum definition throughout the whole focal range.”

“I wanted the camera to seem detached — that’s exactly what the idea was. I did that by making the subject come to me, rather than going to them.”

Milsome’s clinical, detached photography of Full Metal Jacket‘s visceral battle footage lends Kubrick’s film a distant, yet poignant quality, which the cinematographer was afraid might be lost when he used the finely honed Nikon lenses. “I was hoping that detached documentary look would come across, but I worried that those Nikon lenses tend to bit into so much that there’s almost nothing you don’t see, whereas, in documentaries, you can’t always see everything,” Milsome says. “I wanted the camera to seem detached — that’s exactly what the idea was. I did that by making the subject come to me, rather than going to them. There’s an intermediate distance where lenses become very detached, although over a certain focal length you can get too close or too wide and become very integrated into the action. We were aiming for the middle distance where we could reach a focal length that would allow us to remain slightly more divorced from the action and still see it all.”

“We used a take where she looks very strange as she turned around, where the fires blazing in the room seem almost to eat into her face as they bleed in from the background.”

The surviving Marines ultimately confront the sniper inside one of the bombed-out buildings, in what appears to be some sort of decimated temple. The sniper is at first unaware that her enemies have entered the stronghold, but as soon as their presence is detected, the killer of half the platoon whirls about madly to do battle with the rest. The film’s supreme shock moment — the revelation that the sniper is merely a teenage girl — is poetically served by Milsome’s unusual, stroboscopic slow-motion cinematography. “We used a take where she looks very strange as she turned around,” he says, “where the fires blazing in the room seem almost to eat into her face as they bleed in from the background. This wasn’t just achieved by slowing the film down. We actually put the shutter of the camera out of phase with the movement of the film, which created a slight vertical strobe. As she was moving up and down and turning around, the flames seem to be standing still, and when she moved into the flames, they didn’t move with her but seemed to bleed onto her face. The film is actually exposing as it’s moving, which is what gives it that strobe effect. Normally, the film stops when the shutter opens, which freezes the picture., but in this case, the film’s still moving while the shutter’s open. Only slightly out of sync — maybe 25% — but it’s enough to give the effect of light lasting that much longer in the shot.”

The resolution of Private Joker’s moral ambiguity — as symbolized by the “Peace” symbol button on his body armor and the “Born To Kill” moniker he paradoxically sports on his helmet — is evidenced when he kills the young girl who so ruthlessly attacked them. Afterwards, he and the remaining soldiers march through the blasted concrete and twisted metal, a truly hellish landscape of angry orange and red flame, and Milsome’s camera captures the film’s final action with eloquent simplicity. “We really seemed to be lighting that sequence with Calor gas [LPG] and napalm,” Milsome wrily points out. “The buildings the soldiers march past were lit with a tank filled with 3,000 gallons of burning gas, and we had oil burning Dantes which created the big fires that glowed in the background. The Calor burns very red-yellow and the Dantes burn with a black smoke combined with a lot of color. Together, they produced a strong red glow. We did the final shot with a Louma crane, but it wasn’t shot from a great height. Instead, we extended the Louma crane some 20 feet away from the track, and we actually used it to get closeups of our actors on the march without making them come to camera. We also used a Python crane and a straight dolly on this same track, which was a 1,000 feet or so in length. We had a Brute lamp aimed at our actors and tracking with the camera from a long way off — 50 or 60 feet from the lens.”

The ending of Full Metal Jacket is the most disturbing, despairing and cynical of any Kubrick film. In the three decades since Paths Of Glory, the brilliant but naive young filmmaker has apparently lost whatever faith he may have held in the humanity of the human race. At the end of Paths Of Glory, Kubrick’s soldiers are able to rediscover their souls, but in Full Metal Jacket, they have lost theirs irretrievably. When Joker says he faced the enemy and “felt no fear,” we know that the bullet that ended the Vietnamese girl’s life also killed the Joker that resisted the Marine Corps training for so long. As the Americans march through the burning Hell they’ve made, singing a perverse rendition of the “Mickey Mouse Club Song,” the image goes dark and the Rolling Stones beg us to “Paint It, Black.”

Films don’t get any blacker than Full Metal Jacket.

Admired by many critics and filmmakers, Full Metal Jacket established Milsome’s independent career as a cinematographer, leading to assignments on such features as Desperate Hours, Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, Legionnaire and Dungeons & Dragons. He returned to aid Kubrick as a photographic consultant to cinematographer Larry Smith, ASC, BSC on Eyes Wide Shut.

Also member of the BSC, Milsome has been a member of the ASC since 2001.