Photographing Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon

A master filmmaker creates an epic of such spectacular visual beauty that one critic calls it: “The most ravishing set of images ever printed on a single strip of celluloid.”

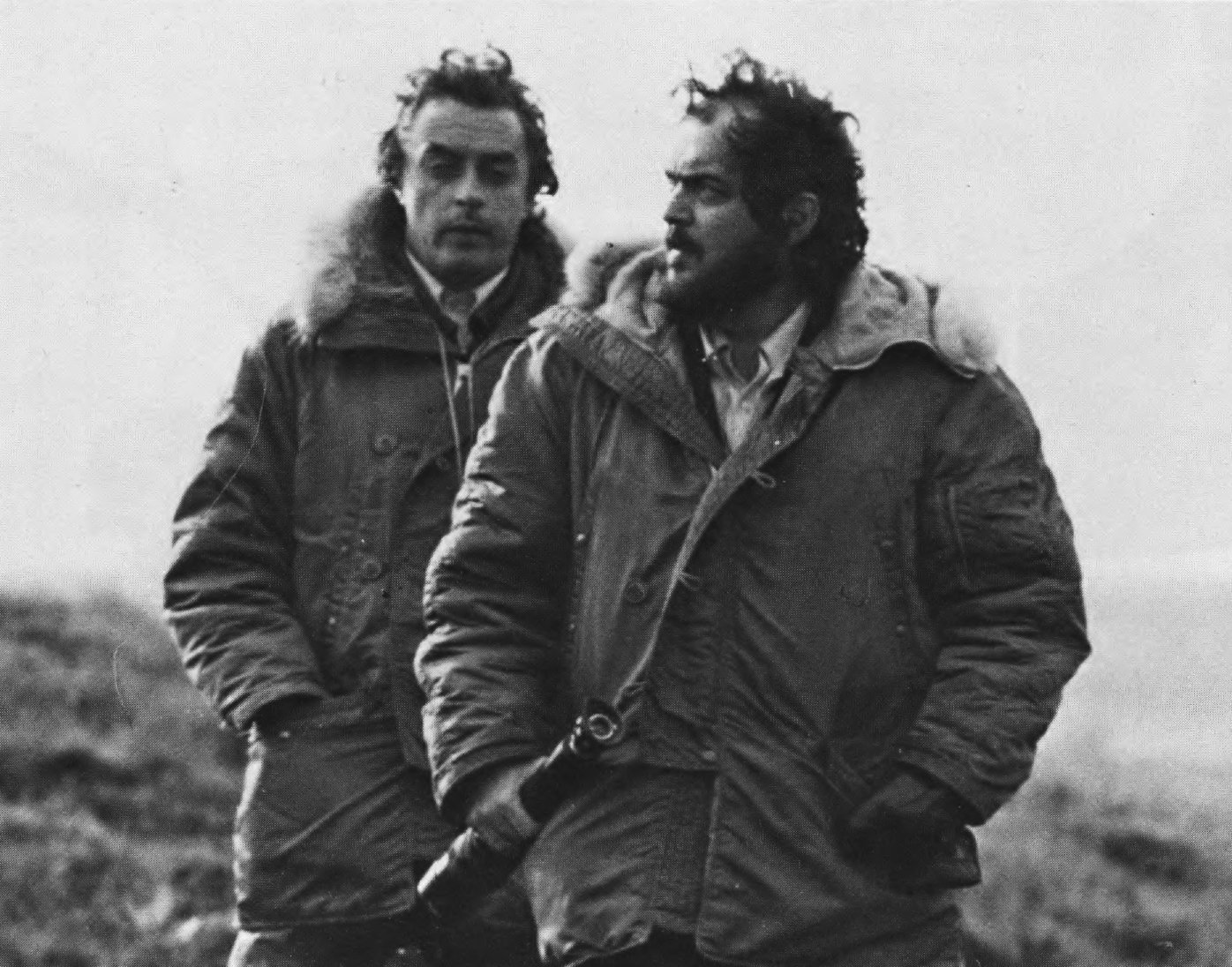

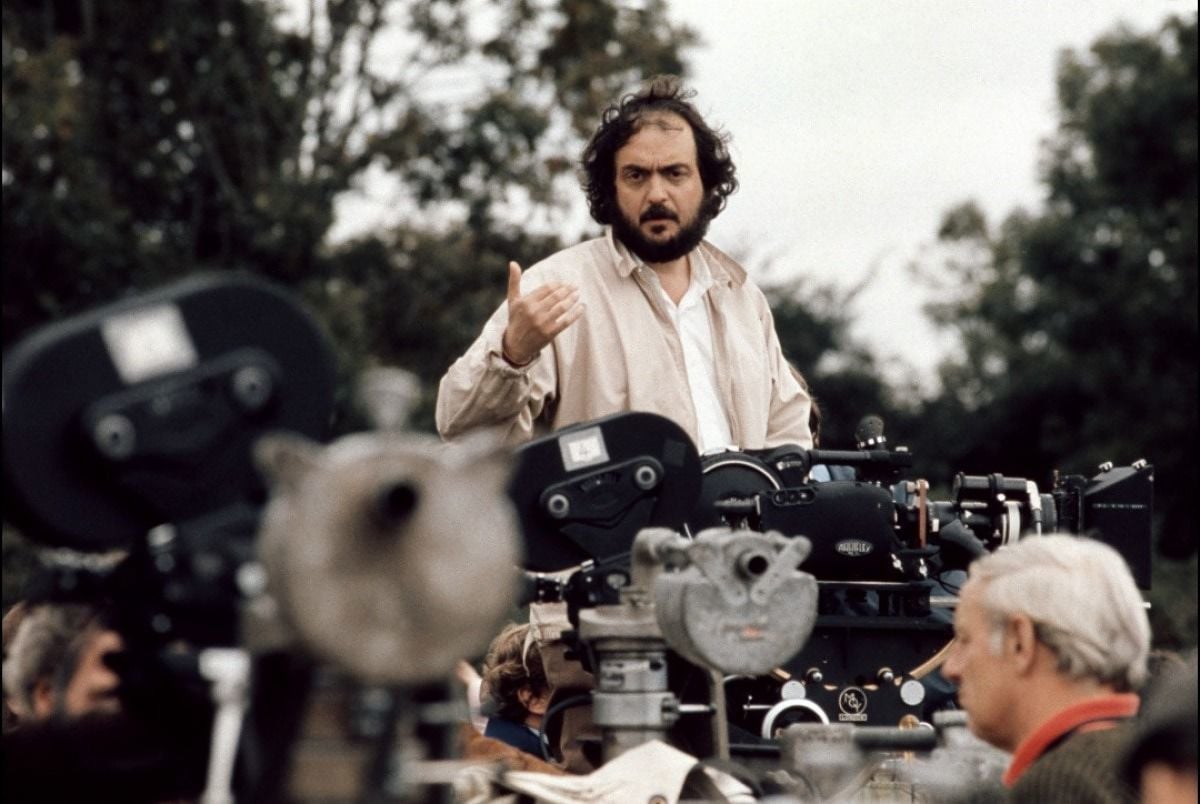

Among all the filmmakers of the world, there is no one quite like Stanley Kubrick. To be more accurate, there is no one even remotely like him.

An early dropout from formal education, largely self-taught, but possessed of a razor-sharp intelligence and voracious curiosity, he has, since the late 1950s steadily risen toward the very pinnacle among the rarefied ranks of world-famed film producer-directors.

Behind him there are 10 feature motion pictures, each one totally different from the others in both content and style. He has never twice made the same type of film.

What sort of man stands behind this astounding body of work? Nobody seems to know — for he is such an intensely private person, living and working, since 1961, encapsulated with his family in a manor house outside of London, that he has become — reluctantly, one suspects — a kind of legend, a disembodied enigma, making public his persona solely in terms of what he puts up there on the screen.

He cares nothing for personal publicity and is all but inaccessible to journalists — which is understandable, considering how many so-called “journalists” hanging onto the fringes of the film world are such unprincipled swine.

Yet, to those few whom he respects and trusts, he comes across as completely free of pretensions, totally honest and forthright.

When, in 1968, after 2001: A Space Odyssey had burst like a rocket across the screens of the world, editor Herb Lightman personally asked Kubrick to share the “secrets” of the film’s stunning technical expertise with American Cinematographer readers, he graciously and generously did so, explaining each unique and dazzling effect in precise detail, holding back nothing (see American Cinematographer, June 1968).

To say that Kubrick is “dedicated” is to sell him short, considering that in Hollywood a dedicated producer is all too often one who forgoes his weekly poker game in order to count the preview cards of his latest movie.

The term “complete commitment” comes closer to describing Kubrick’s symbiotic relationship with film — but “total immersion” is even more apt. Taking as long as four years to make a single film, (2001, for example), he eats, sleeps and breathes the project, once into it. An almost fanatical perfectionist, he drives his co-workers seemingly beyond the limits of their endurance toward heights of achievement they never imagined, let alone hoped to attain.

Stanley Kubrick does not simply create films — he creates entire worlds on film. In Doctor Strangelove he creates a world at once hysterically funny and nightmarish, a quite plausible preview of the beginning of the end of life on this planet. In 2001 he creates a world of the not-so-distant future — cold and computerized, with robot-like astronauts reaching almost mindlessly out toward the cosmic unknown. In A Clockwork Orange he creates a 1984-ish world of senseless violence that is only a silly millimeter away from the chronic craziness and terrorism that prevail globally at this very moment.

And now comes Barry Lyndon.

It is a film on a grand scale which abounds in meticulous technical craftsmanship and — even more important — the tender loving care of Stanley Kubrick and his loyal co-craftsmen.

In his cover story for the December 15, 1975 issue of Time magazine, noted film critic-historian Richard Schickel wrote: “In it, he [Kubrick] demonstrates the qualities that eluded Thackeray: singularity of vision, mature mastery of his medium, near-reckless courage in asserting through his work a claim not just to the distinction critics have already granted him but to greatness that time alone can — and probably will — confirm.”

Underlying this statement is the realization that Kubrick has taken a basically talky novel and magically transformed it into an intensely visual film.

Schickel went on to write: “The structure of the work is truly novel. In addition, Kubrick as assembled perhaps the most ravishing sets of images ever printed on a single strip of celluloid. These virtues are related: the structure would not work without Kubrick’s sustaining mastery of the camera, lighting and composition; the images would not be so powerful if the director had not devised a narrative structure spacious enough for them to pile up with overwhelming impressiveness.”

The operative phrase out of that assertion is: “The most ravishing set of images ever printed on a single strip of celluloid.” — which is quite possibly true, because Barry Lyndon is a delicious feast for the eye. Each composition is like a painting by one of the Old Masters, and they link one onto the other like the tiles of a wondrous mosaic.

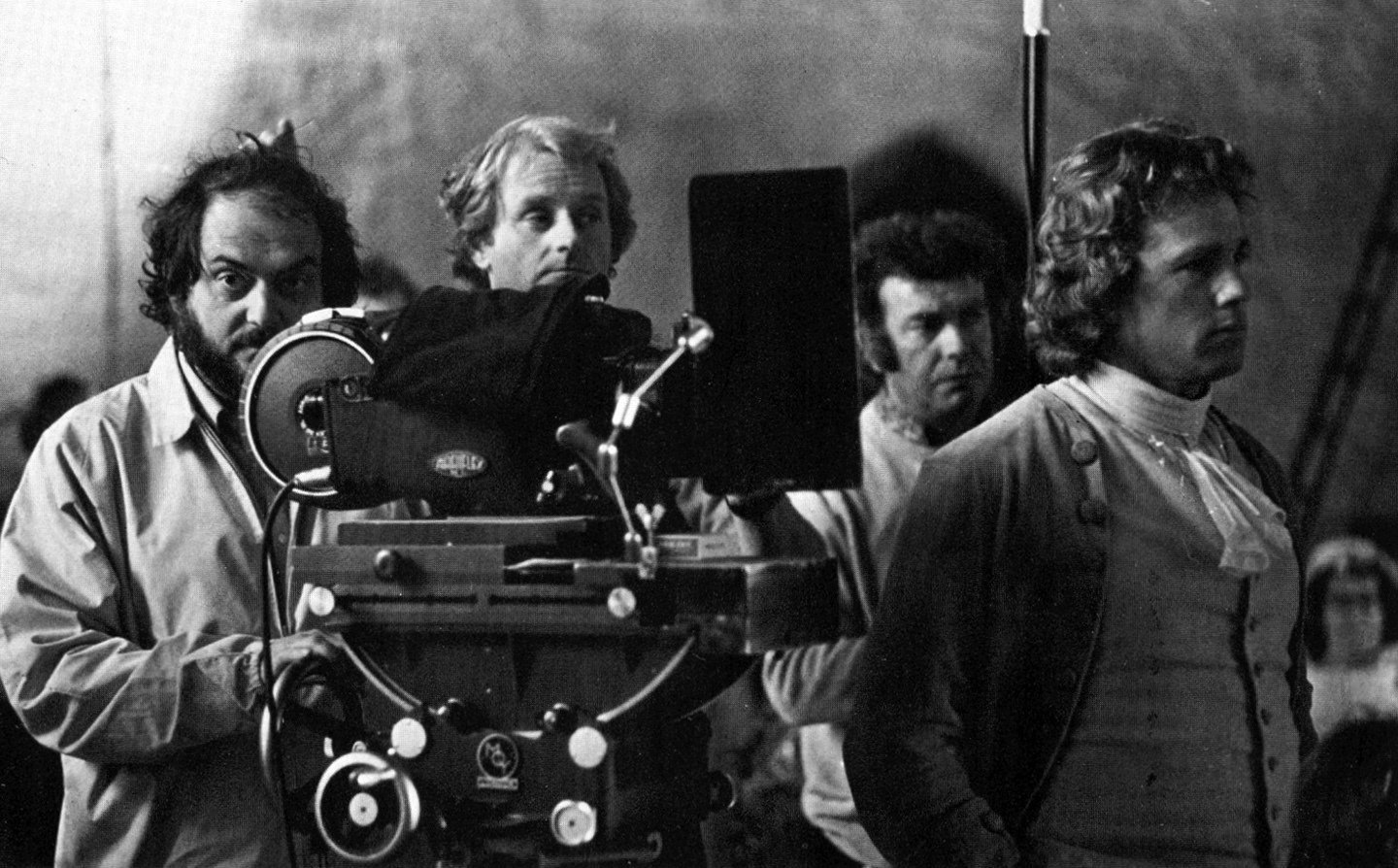

Pictorially, the elegant result emerges from a close collaboration between Kubrick (no mean photographer himself) and director of photography John Alcott, BSC.

Aside from the sheer beauty of the images, the problems of getting some of them onto the screen were considerable and unique. In the following interview, conducted by American Cinematographer editor Herb Lightman, Alcott discusses those problems, as well as the techniques utilized to make Barry Lyndon the pictorially beautiful film that it is.

American Cinematographer: You’ve worked with Stanley Kubrick on three pictures: 2001: A Space Odyssey, A Clockwork Orange and now Barry Lyndon. Can you tell me a bit about that working relationship?

JOHN ALCOTT, BSC: We have a very close working relationship, which began on 2001. I had been assisting Geoffrey Unsworth [BSC] on that picture and then, when Geoff had to leave after the first six months, I was asked to carry on — so it was Stanley Kubrick who gave me my break. Our working relationship is close because we think exactly alike photographically. We really do see eye-to-eye photography.

What about the pre-planning phase of Barry Lyndon?

There was a great deal of testing of possible photographic approaches and effects — the candlelight thing, for example. Actually, we had talked about shooting solely by candlelight as far back as 2001, when Stanley was planning to film Napoleon, but the requisite fast lenses were not available at that time. In preparation for Barry Lyndon we studied the lighting effects achieved in the paintings of the Dutch masters, but they seemed a bit flat — so we decided to light more from the side.

You photographed both A Clockwork Orange and Barry Lyndon for Kubrick and, obviously, the photographic styles of these two pictures were quite different from each other. Comparing the two, purely as a point of interest, how would you describe those stylistic differences?

Well, A Clockwork Orange employed a darker, more obviously dramatic type of photography. It was a modern story, taking place in an advanced period of the 1980s — although the period was never actually pinpointed in the picture. That period called for a really cold, stark style of photography; whereas, Barry Lyndon is more pictorial, with a softer, more subtle rendition of light and shadow overall than A Clockwork Orange. As I saw it, the story of Barry Lyndon took place during a romantic type of period — although it didn’t necessarily have to be a romantic film. I say “a romantic period” because of the quality of the clothes, the dressing of the sets and the architecture of that period. These all had a kind of soft feeling. I think you probably could have lighted Barry Lyndon in the same way as A Clockwork Orange, but it just wouldn’t have looked right. It wouldn’t have had that soft feeling.

How did you translate “that soft feeling” into cinematic terms, and what technical means did you use to achieve it?

In most instances we were trying to create the feeling of natural light within the houses, mostly stately homes, that we used as shooting locations. That was virtually their only source of light during the period of the film, and those houses still exist, with their paintings and tapestries hanging. I would tend to re-create that type of light, all natural light actually coming through the windows. I’ve always been a natural light source type of cameraman — if one can put it that way. I think it’s exciting, actually, to see what illumination is provided by daylight and then try to create the effect. Sometimes it’s impossible when the light outside falls below a certain level. We shot some of those sequences in the wintertime, when there was natural light from perhaps 9 o’clock in the morning until 3 o’clock in the afternoon. The requirement was to bring the light up to a level so that we could shoot from 8 o’clock in the morning until something like 7 o’clock in the evening — while maintaining the consistent effect. At the same time, we tried to duplicate the situations established by research and reference to the drawings and paintings of that day — how rooms were illuminated and so on. The actual compositions of our setups were very authentic to the drawings of the period.

In other words, then, you would take your cue from the way the natural light actually fell and then you would build that up or simulate it with your lighting units in an attempt to get the same effect, but at an exposurable level?

Yes. In some instances, what we created looked much better than the real thing. For example, there’s a sequence that takes place in Barry’s dining room, when his little boy asks if his father has brought him a horse. That particular room had five windows, with a very large window in the center that was much greater in height than the others. I found that it suited the sequence better to have the light coming from one source only, rather than from all around. So we controlled the light in such a way that it fell upon the center of the table at which they were having their meal, with the rest of the room falling off into nice subdued, subtle color.

In creating that particular effect, did you use any of the light actually coming through the windows?

No, it was simulated by means of Mini-Brutes. I used Mini-Brutes all the time, with tracing paper on the windows — plastic material, actually. I find it to be a little bit better than the tracing paper.

Was most of the picture shot in actual locations, or did you have to build some sets?

Oh, no — every shot is an actual location. We didn’t build any sets whatsoever. All of the rooms exist inside actual houses in Ireland and the southwest of England.

What about the physical problems of shooting inside those actual stately homes?

Well, we did have problems, although they didn’t affect me too much. For instance, many of those stately homes are open to the public. We couldn’t restrict the public from going through — so we had to cater to them. We would use certain rooms with visitors virtually walking past in the corridor. They would simply close off that one room and have the public bypass it. However, at times our shooting schedule would be limited to the point where we had to work when they weren’t touring. They would go around in groups and we would virtually shoot when they were changing over from one group to another. In many of the locations, though, we had complete freedom of the house. We didn’t really have too many problems, except for having to build very large rostrums for the lighting in certain rooms. I also had rostrums built around the exterior windows. They could be wheeled out of the way for reverse angles when we were shooting toward the windows and wanted to show the view outside as well. Such was the case in the sequence that takes place in Countess Lyndon’s bedroom.

Did you have to gel the windows, or were you using a daylight balance?

In the actual interiors, most of the time, we did gel the windows, although there were a very few instances when we didn’t do it. We had neutral density filters made, as well — ND3, ND6 and ND9 — so that we had a complete range to accommodate whatever light situation prevailed outside the windows. Also, on all the exterior shooting, I never used an 85 filter.

What was your reason for not using 85?

One reason was to get an overall consistent balance throughout the entire picture. In that sense, I tend to use it as I use forced development — that is, in every scene (including those that don’t actually need it), in order to maintain a consistency of visual character throughout. The second reason was simply that the exterior light was sometimes so low that I needed the extra two-thirds of a stop. Although we mostly used the zoom lens outdoors, there were many instances in which we ended up shooting wide open with the Canon T/1.2 lens.

In other words, the light was sometimes so dull, so overcast that you had to open up that lens all the way. Is that right?

Oh, yes — all the way. That was especially true in the holdup ambush sequence. We started off with a good day and there was plenty of light in the beginning, but the last part of that sequence was shot with the T/1.2 lens wide open. In order to match the brilliance of the normal daylight one had to be very fully exposed. I needed that fast lens.

Can you tell me to what extent you used diffusion in shooting Barry Lyndon?

When I went around looking at locations with Stanley we discussed diffusion, among other things. The period of the story seemed to call for diffusion, but on the other hand, an awful lot of diffusion was being used in cinematography at the time. So we tended not to diffuse. We didn’t use gauzes, for example. Instead I used a No.3 Low Contrast filter all the way through — except for the wedding sequence, where I wanted to control the highlights on the faces a bit more. In that case, the No.3 Low Contrast filter was combined with a brown net, which gave it a slightly different quality. We opted for the Low Contrast filter rather than actual diffusion because the clarity and definition in Ireland create a shooting situation that is very like a photographer’s paradise. The air is so refined, I think, because Ireland is in the Gulf Stream. The atmosphere is actually perfect and we thought it would be a pity to destroy that with diffusion, especially for the landscape photography.

That’s rather refreshing. There seems to be a tendency these days, despite the nice sharp lenses that are available, to just fuzz everything out as a matter of course.

Yes, it’s done a lot. I’ve even done it myself in shooting commercials. We did discuss the possibility for Barry Lyndon, but then we thought: “Well, it’s been done before so many times; let’s try for something different. Let’s go into low contrast.” We tested many filters and of all those we tested the Tiffen Low Contrast filters came out the best quality-wise. With the Tiffen filters we didn’t lose any quality whatsoever, even when shooting wide open, in fact. They were the best.

Did you use any of the 5247 color negative, or was it all 5254?

We used the 5254, because the 5247 wasn’t available even at the time when we finished shooting. It came out something like two months after we had finished the main shooting of the film. Now I find that, because of the fineness of the grain with the 5247, I would have had to use a No.5 Tiffen Low Contrast filter in order to get the same effect I got using the No.3 with the old stock.

Do you find, as many other cinematographers have found, that the 5247 negative has an inherently higher contrast than the 5254?

Well, they say it’s higher contrast, but I really think it’s not so much the contrast as the fact that the grain is so much finer. If the grain is finer, this will increase the apparent contrast. In other words, you’ve got to dress and color your sets to accommodate the film stock. Even the tiniest ornaments which are red will kick out on the new stock, whereas on the old stock they wouldn’t. This is because of the finer grain. It’s the color, in fact, which is building up the contrast. However, I can’t understand why anybody wouldn’t go for the finer grain, because that’s what it’s all about. The thing is to try to make it work by knocking down the contrast in some other way. We must either modify the lighting or design the set in a way to tone it down. For instance, in some of the interiors used for shooting Barry Lyndon there were lots of white areas — fireplaces and such. If you put a light through a window these would stick out like a sore thumb, as they say. So, most of the time, I covered them with a black net — the white marble of the fireplaces, the very large white three-foot-wide panels on the walls, and the door frames that were white. I covered them with a black net having about a half-inch mesh. You could never see it photographically unless you were really close to it — but in the long shots it wasn’t visible at all. It did wonders in toning down the white. I also used graduated neutral density filters on certain light parts of the set when the illumination was coming from a natural light source and there was no way to gobo it off. For example, if the light source were coming from the left and hitting something that it was not possible to put a net over, I would put a neutral density filter on the right side — an ND3 or ND6, depending upon the brightness.

You would actually use graduated neutral density filters for shooting interiors? That’s not done very often, is it?

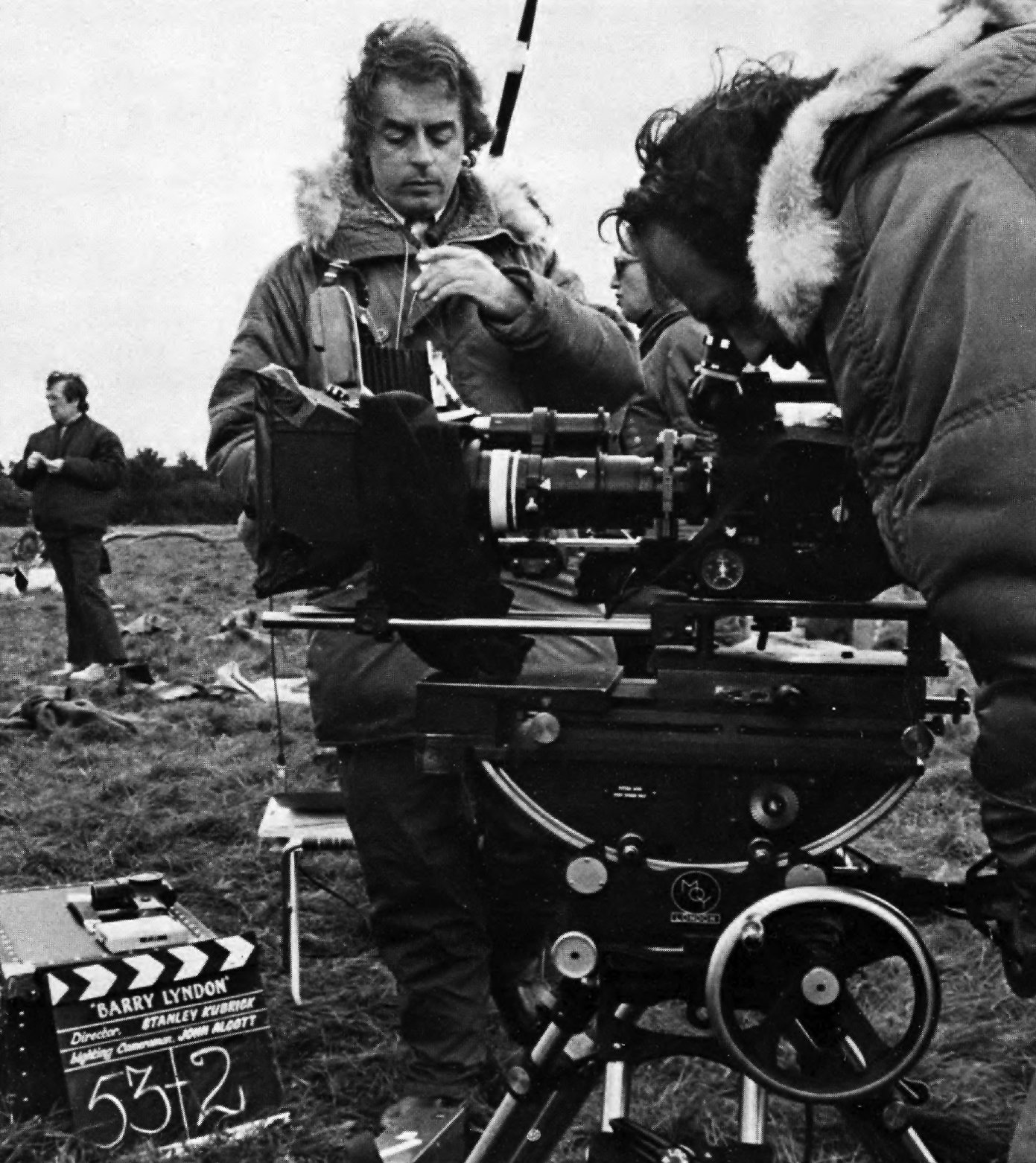

I don’t think so — no. I know that when I use them now in different types of work that I do, some of the people on the set wonder what I’m up to, using graduated filters for interiors. But they work very well indeed. In fact, we had a matte box made to accept the three filters on the Arriflex 35BL. Incidentally, we used the Arriflex 35BL all the way through the picture.

Can you give me some of your impressions of that camera?

I think it’s a fantastic camera. To me, it’s a cameraman’s camera — mainly because the optical system is so good. Some optical systems give you a much more exaggerated tunneling effect than others, and I even came across someone the other day who prefers that long tunneling effect because it makes him feel like he’s in a cinema. Personally, I prefer it when my eye is filled with the actual picture image. You find that this only really occurs with the Arriflex 35BL. Another feature I like about the camera is that you’ve got the aperture control literally at your fingertips. It’s got a much larger scale and, therefore, a finer adjustment than most cameras. This feature is especially important when you’re working with Stanley Kubrick, because he likes to continue shooting whether the sun is going in or out. In Barry Lyndon, during the sequence when Barry is buying the horse for his young son, the sun was going in and out all through the sequence. You’ve got to cater to this. That old bit that says you cut because the sun’s gone in doesn’t go anymore.

Instead, you try to ride it out by varying the aperture opening during the shooting of the scene?

Yes, that’s why the Arriflex 35BL offers such an advantage. It’s got a finer aperture adjustment — more so than most other cameras — which allows you to cater to light variations while you’re actually shooting. On most lenses there’s not a great distance between one aperture stop and the next. There isn’t actually on the Arriflex 35BL lenses either, but it’s the gearing mechanism on the outside that offers the larger scale and, therefore, the possibility of more precise adjustment. It’s like converting a ¼-inch move into a 1-inch move.

What about the use of the zoom lens in this film?

Oh, yes — we used it a great deal. The Angenieux 10-to-1 zoom was used on the Arriflex 35BL, in conjunction with Ed DiGiulio’s Cinema Products “Joy Stick” zoom control, which is an excellent one. It starts and stops without a sudden jar, which is very important, and you can manipulate it so slowly that it almost feels like nothing is happening. This is very difficult to do with some of the motorized zoom controls. I find that this one really works.

What types of lighting equipment did you use?

We used Mini-Brutes and we used a lot of Lowel-Lights — all the time. I used the Lowel-Lights in umbrellas for overall fill. I always use the umbrellas — ever since A Clockwork Orange. I would find that the Lowel-Light has a far greater range of illumination from flood to spot than any other light I know of. In fact, it’s the only light of its type that gives you a fantastic spot, if you need it, and an absolute overall flood. Also, when you put a flag in front of most quartz lights you get a double shadow — but not with the Lowel-Lights. But then, of course, they were designed by a cameraman.

What about the use of the moving camera in Barry Lyndon?

We used it in certain sequences, but not too many. We had one very long tracking shot in the battle sequence, with the cameras on an 800-foot track. There were three cameras on the track, moving with the troops. We used an Elemack dolly, with bogie wheels, on ordinary metal platforms, and a five-foot and sometimes six-foot wheel span, because we found that this worked quite well in trying to get rid of the vibrations when working on the end of the zoom. It seemed to take the vibration out better than going directly onto the Elemack.

Do I understand that you were racked out to the end of the zoom on that tracking shot?

Yes, virtually all close-ups made from the track during that battle sequence were on the 250mm end of the zoom.

That is really living dangerously.

I made a test beforehand with the camera traveling on an ordinary track and one with this base, and the difference was quite amazing. That’s what got us round to building these platforms and using the Elemack with the bogie wheels on the four corners. They are really quite handy for doing all kinds of shots.

What would you say was your most difficult sequence to shoot in this film?

I think the most difficult bit was the scene in the club when Barry comes over to confront the nobleman sitting at the other table, is given the cold shoulder and then goes back to his own table. That involved a 180-degree pan and what made it difficult was the fluctuations in the weather outside. There were many windows and I had lights hidden behind the brickwork and beaming through the windows. The outside light was going up and down so much that we had to keep changing things to make sure the windows wouldn’t blow out excessively. This was the most difficult to do, because any time I changed the gels on the windows, I also had to change the lights outside in order to avoid getting too much light inside and not enough outside. I would say that was the most difficult shot in the whole picture, in terms of lighting. What complicated it further was the fact that this was one of those stately houses that had the public coming through and visiting at the same time we were shooting.

Did you use much colored light during the filming?

Yes, many times. An example that comes to mind is the scene in Barry’s room after he has had his leg amputated. I used a light coming through the window with an extra ½ sepia over it in order to give a warm effect to the backlight and sidelight. In other words, a 50% overcorrection. A similar effect was used on Barry in the sequence when his boy is dying. In some instances, I let the natural blue daylight come through in the background without correcting it. The result looked pleasing and it created a more “daylight” sort of effect.

I can’t recall any night-for-night shots in the picture. Were there any, perhaps, that didn’t appear in the final cut?

There weren’t really any night shots. There’s that one twilight scene of Barry by the fire meditating after he’s joined up, but that was shot at the “magic hour” and wasn’t a true night shot.

Now we come to the scenes which have caused more comment than anything else in this overall beautiful film — namely the candlelight scenes. Can you tell me about these and how they were executed?

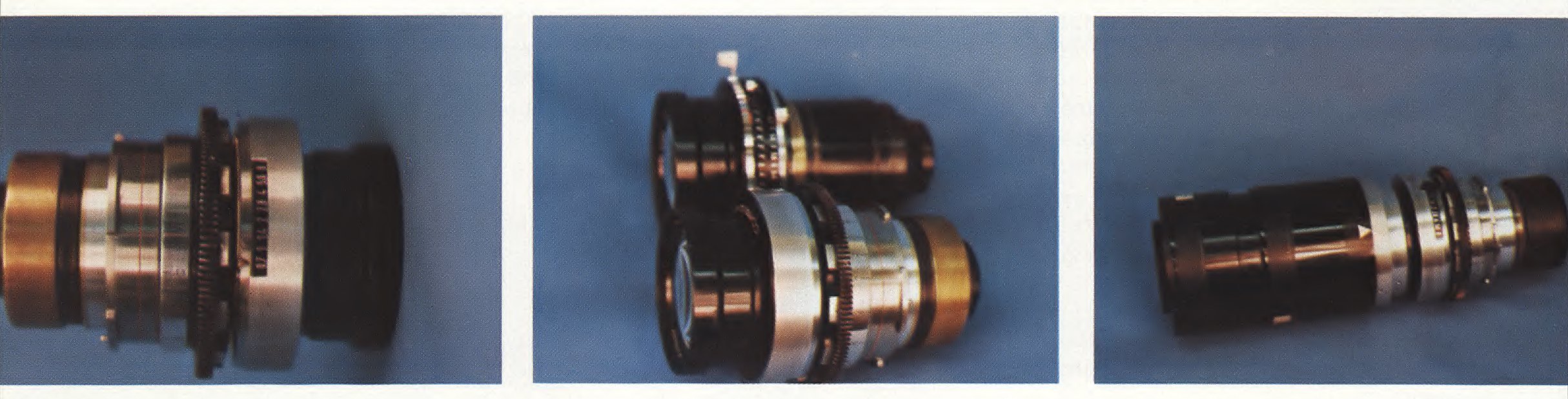

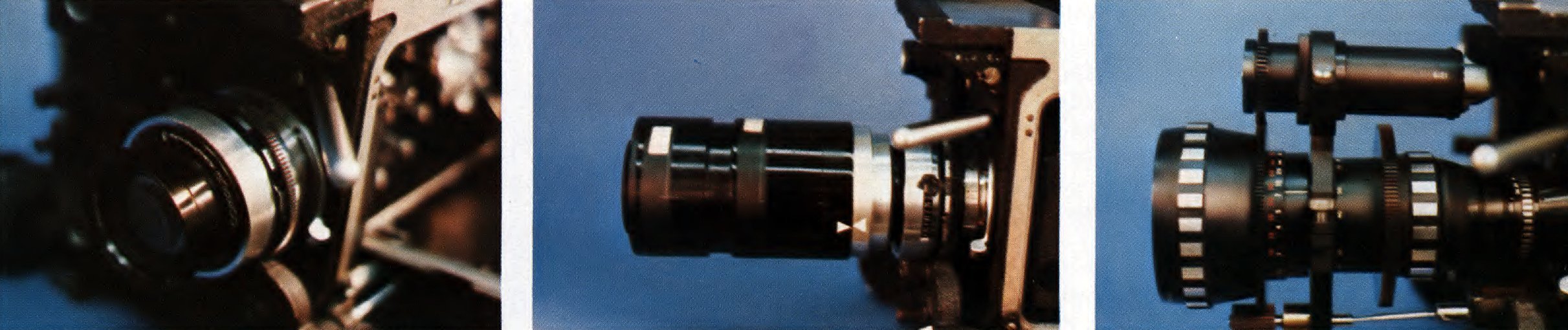

The objective was to shoot these scenes exclusively by candlelight — that is, without a boost from any artificial light whatsoever. As I mentioned earlier, Stanley Kubrick and I had been discussing this possibility for years, but had not been able to find sufficiently fast lenses to do it. Stanley finally discovered three 50mm t/0.7 Zeiss still-camera lenses which were left over from a batch made for use by NASA in their Apollo moon-landing program. We had a non-reflexed Mitchell BNC which was sent over to Ed DiGiulio to be reconstructed to accept this ultra-fast lens. He had to mill out the existing lens mounts, because the rear element of this t/0.7 lens was virtually something like 4mm from the film plane. It took quite a while, and when we got the camera back we made quite extensive tests on it.

The Zeiss lens was like no other lens in a way, because when you look through any normal type of lens, like the Panavision T/1.1 or the Angenieux f/0.95, you are looking through the optical system and by just altering the focus you can tell whether it’s in or out of focus. But when you looked through this lens it appeared to have fantastic range of focus, quite unbelievable. However, when you did a photographic test you discovered that it had no depth at all — which one expected anyway. So we literally had to scale this lens by doing hand tests from about 200 feet down to about 4 feet, marking every distance that would lead up to the 10-foot range. We had to literally get it down to inches on the actual scaling.

You say that the focal length was 50mm?

It was 50mm, but then we acquired a projection lens of the reduction type, which Ed DiGiulio fitted over another 50mm lens to give us a 36.5mm lens for a wider-angle coverage. The original 50mm lens was used for virtually all the medium shots and close shots.

And those scenes were illuminated entirely by candlelight?

Entirely by the candles. In the sequence were Lord Ludd and Barry are in the gaming room and he loses a large amount of money, the set was lit entirely by the candles, but I had metal reflectors made to mount above the two chandeliers, the main purpose being to keep the heat of the candles from damaging the ceiling. However, it also acted as a light reflector to provide an overall illumination of toplight.

How many foot-candles — no pun intended — would you say you were using in that case?

Roughly, three foot-candles was the key. We were forcing the whole picture one stop in development. Incidentally, I found a great advantage in using the Gossen Panalux electronic meter for those sequences because it goes down to half foot-candle measurements. It’s a very good meter for those extreme low-light situations. We were using 70-candle chandeliers, and most of the time I could also use either five-candle or three-candle table candelabra as well. We actually went for a burnt-out effect, a very high key on the faces themselves.

What were some of the other problems attendant to using this ultra-fast lens to shoot entire by candlelight?

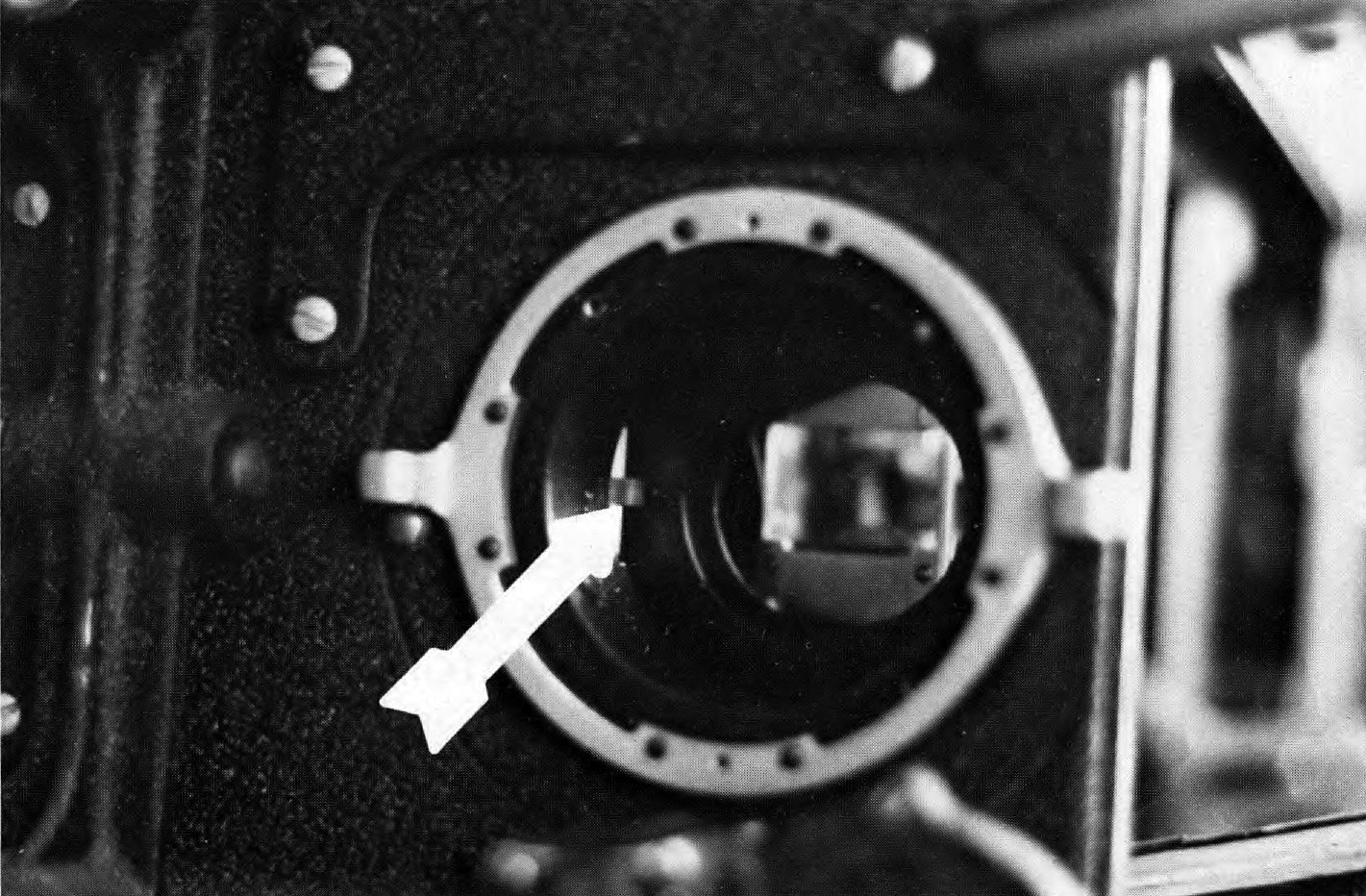

There was, first of all, the problem of finding a side viewfinder that would transmit enough light to show us where we were framed. The conventional viewfinder would not do at all, because it involves prisms which cause such a high degree of light loss that very little image is visible at such low light levels. Instead, we had to adapt to the BNC a viewfinder from one of the old Technicolor three-strip cameras. It works on a principle of mirrors and simply reflects what is “sees,” resulting in a much brighter image. There is very little parallax with that viewfinder, since it mounts so close to the lens.

What about the depth of field problem?

As I suggested before, that was indeed a problem. The point of focus was so critical and there was hardly any depth of field with that f/0.7 lens. My focus operator, Doug Milsome [ASC], used a closed-circuit video camera as the only way to keep track of the distances with any degree of accuracy. The video camera was placed at a 90-degree angle to the film camera position and was monitored by means of a TV screen mounted above the camera lens scale. A grid was placed over the TV screen and by taping the various artists’ positions, the distances could be transferred to the TV grid to allow the artists a certain flexibility of movement, while keeping them in focus. It was a tricky operation, but according to all reports, it worked out quite satisfactorily.

Alcott earned an Academy Award for his expert work in the film:

In a clip from the British Society of Cinematographers linked here, Douglas Milsome, ASC, BSC discusses his work on Barry Lyndon as a “focus puller,” or camera assistant. Also working as an AC for Kubrick and Alcott on A Clockwork Orange (1971) and The Shining (1980), Milsome would later collaborate with the director again as the lighting cameraman on Full Metal Jacket (1987), and as a consultant on Eye Wide Shut (1999).

In 2019, Barry Lyndon was selected as one of the ASC 100 Milestone Films in Cinematography of the 20th Century.

Two Special Lenses for Barry Lyndon

By Ed DiGiulio

President, Cinema Products Corp.

How the stringent demands of a purist-perfectionist filmmaker led to the development of two valuable new cinematographic tools.

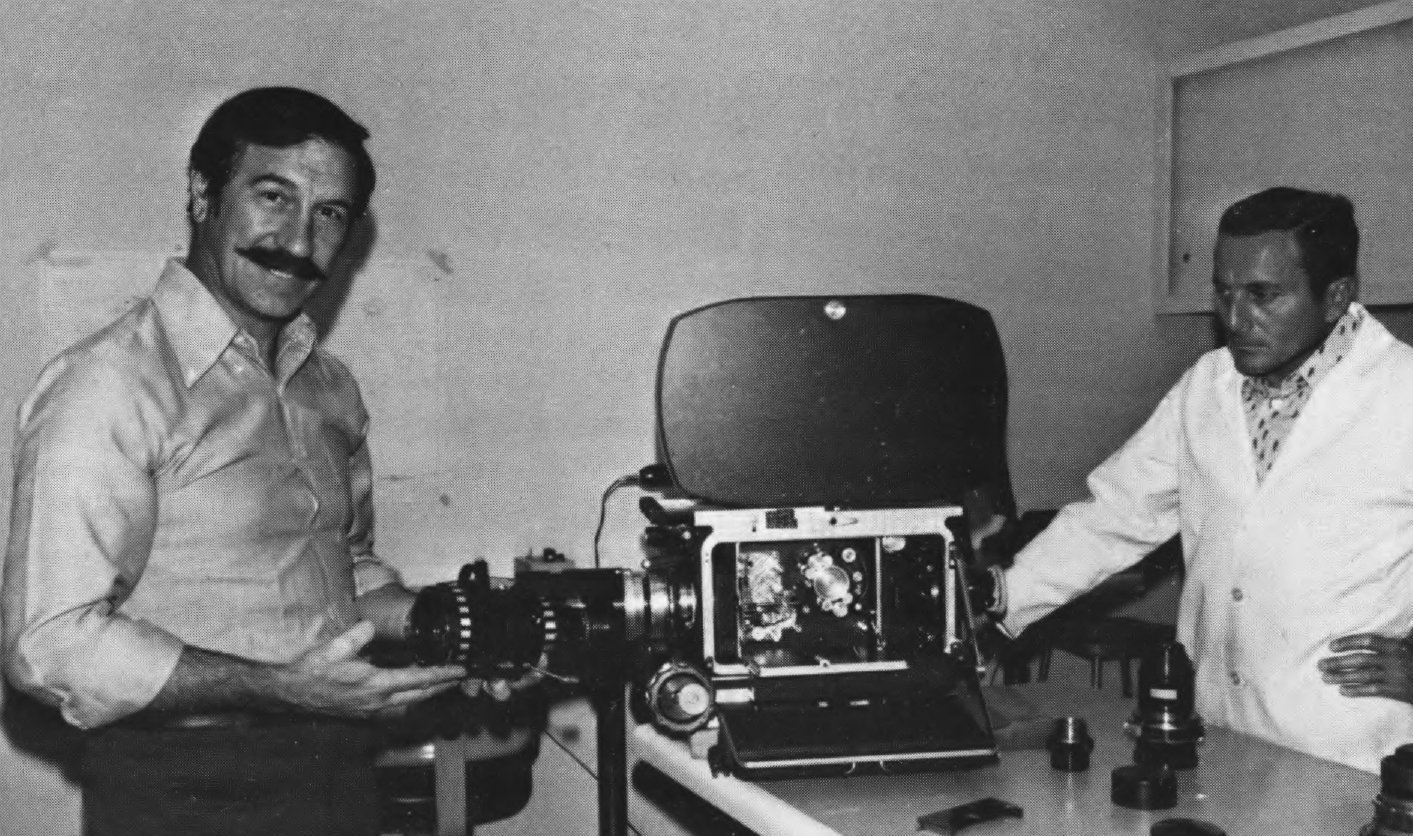

My first contact with Stanley Kubrick was when he was referred to me by our mutual friend Haskell Wexier, ASC, during Kubrick's preparation for A Clockwork Orange. Haskell indicated to him that I and my company were very responsive to the demanding needs of professional filmmakers, especially when it came to coming up with unique solutions to difficult probems.

For Clockwork we purchased a standard Mitchell BNC for Kubrick and overhauled it, but did not reflex it or modify it in any special way. Kubrick's attitude has always been that he would rather work with a non-reflexed BNC and thereby gain tremendous flexibility and latitude in adaptation of special lenses to the camera — as was subsequently the case on Barry Lyndon. For Clockwork we also supplied the major accessory items for which we are well known, such as the “Joy Stick” zoom control, the BNC crystal motor and the Arri crystal motor.

At the very early stages of his preparation for Barry Lyndon, Kubrick scoured the world looking for exotic, ultra-fast lenses, because he knew he would be shooting extremely low light level scenes. It was his objective, incredible as it seemed at the time, to photograph candle-lit scenes in old English castles by only the light of the candles themselves! A former still photographer for Look magazine, Kubrick has become extremely knowledgeable with regard to lenses and, in fact, has taught himself every phase of the technical application of his filming equipment. He called one day to ask me if I thought I could fit a Zeiss lens he had procured, which had a focal length of 50mm and a maximum aperture of f/O.7. He sent me the dimensional specifications, and I reported that it was impossible to fit the lens to his BNC because of its large diameter and also because the rear element came within 4mm of the film plane. Stanley, being the meticulous craftsman that he is, would not take “No” for an answer and persisted until I reluctantly agreed to take a hard look at the problem.

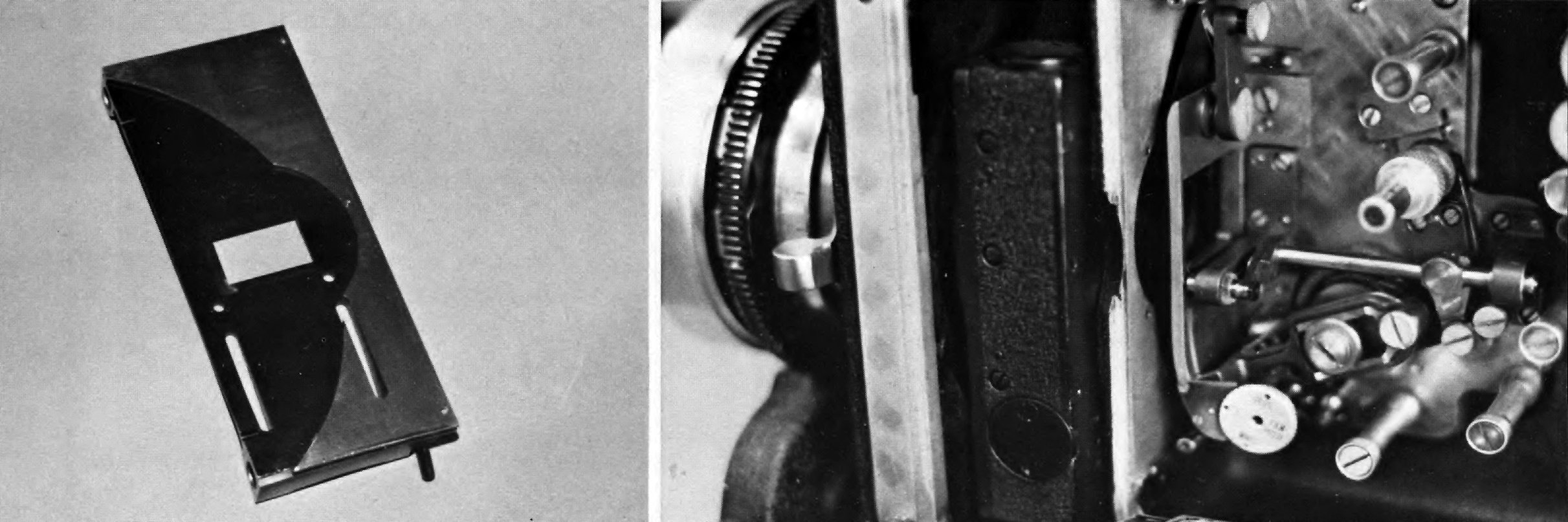

When the lens arrived, we could see it was designed as a still camera lens, with a Compur shutter built into the lens. The diameter of the lens was so large that it would just barely fit into the BNC lens port, leaving no room for an additional focusing shell. As a consequence, we had to design a focusing arrangement so that the entire lens barrel rotates freely in the lens port. To avoid possible binds that might result from this unconventional mode of operation, we added a second locating pin to the standard BNC lens flange, so that the two pins securely held the lens barrel concentric with the lens port during operation.

The problem of the close proximity of the rear element to the film plane was a much more difficult matter to resolve. To begin with, we removed the adjustable shutter blade, leaving the camera with only a fixed maximum opening. We then had to machine the body housing and the aperture plate a considerable distance inward so that the fixed shutter blade could be pulled back as far as possible toward the film plane.

Naturally, the Compur shutter had to be dismantled and the iris leaves altered so that they could be manually operated in the normal manner. Calibrating the focus scale on the lens presented quite a problem, too. A lens as fast as this has an extremely shallow depth of field when shooting wide open, so Kubrick understandably wanted to have as broad a band spread on the scale as possible. To do this we used an extremely fine thread for the focusing barrel and this resulted in a scale which required two complete revolutions to go from infinity down to approximately 5’. We had to stop at 5’ or it would have taken several more revolutions to bring it to the near focus point. Kubrick agreed that this was as close a focus as he would require, and that stopping at two revolutions would make the scale less ambiguous.

Remembering that this lens was to be used on a non-reflexed BNC and, further, that the rear element of the lens came within 4mm of the film plane, an additional problem was that the camera could not be racked over to the viewing position if the lens were in its normal filming position. Accordingly, we designed a safety interlock switch so that the lens had to be rotated a full nine revolutions out before the micro switch would trip, permitting the camera to be racked over. In this manner, we protected the rear element of the lens from being inadvertently smashed if the operator attempted to rack over before the lens was moved forward sufficiently.

The lens and camera were sent to Kubrick, who film-tested it and reported that the results were fantastic. He found, however, that he did have to recalibrate our scale, apparently because of some slight shift in camera position during shipment. We subsequently determined that it was necessary for us to tighten up the dovetail gibs upon which the camera racks back and forth to the point where racking over became fairly stiff, since the flange focal depth of the lens was so extremely critical.

At this point, Kubrick complained that the single 50mm focal length was too limiting and that what he required was a wider-angle lens of the same speed. He began thinking in terms of various anamorphosing schemes or other optical tricks to widen the angle of the lens we had. I told him that before doing anything as mind-boggling as this I would check with some of the optical experts I knew to see if there were a simpler way. As luck would have it, Dr. Richard Vetter of Todd-A-O, a man whose optical expertise I’ve always held in high esteem, suggested to me that the result I was trying to achieve could probably be accomplished by using a projection lens adapter, designed by the Kollmorgen Corporation, which was originally intended to modify the focal length of 70mm projection lenses in theatres so that the image format could exactly match the size of the screen.

We purchased one of these adapters, mounted it to the front of the lens, and after some optical and mechanical manipulation we were pleased to see that the effective focal length of our composite lens system was 36.5mm. The aperture of the new 36.5mm lens remained at f/0.7 and its effective aperture was reduced only slightly by the minor light absorption in the two front elements. We sent this lens on to Kubrick and, again, he was ecstatic with the results. However, being the demanding technical genius that he is, Stanley urged us to go further and see if we could come up with a still wider angle lens. Again I turned to Dr. Vetter, and this time he provided me with a Dimension 150 lens adapter which, when mounted to the front of still another Zeiss 50mm prime lens, gave us an effective focal length of 24mm. However, at this point, our improvisational engineering techniques began to catch up with us and Kubrick determined that the lens gave a bit too much distortion, so that he would not wish to intercut photography from this lens with photography from the other two.

As a technician and not a creative artist, I asked Kubrick the obvious question: Why were we going to all this trouble when the scene could be easily photographed with the high-quality super-speed lenses available today (such as those manufactured by Canon and Zeiss) with the addition of some fill light. He replied that he was not doing this just as a gimmick, but because he wanted to preserve the natural patina and feeling of these old castles at night as they actually were. The addition of any fill light would have added an artificiality to the scene that he did not want. To achieve the amount of light he actually needed in the candlelight scenes, and in order to make the whole movie balance out properly, Kubrick went ahead and push-developed the entire film one stop — outdoor and indoor scenes alike. I am sure that everyone who has seen the results on the screen must agree that Kubrick has succeeded in achieving some of the most unique and beautiful imagery in the cinematic art.

On A Clockwork Orange, Kubrick had made effective use of a 20-to-1 zoom lens that he had rented from Samuelson Film Service in London. The closing scene of the movie, with a long slow pull-back from the hero of the story as he walks along the river, is a prime example of its application.

Kubrick likes to own all of his equipment, even to the extent of building his own very modest location vehicle. This may be partly an ego trip, but I think it is mainly due to the fact that he is meticulous about the care and maintenance of his equipment and is, therefore, very uncomfortable with equipment that someone else has used. In any event, for whatever reason, Kubrick insisted that I build him a 20-to-1 zoom lens for Barry Lyndon. What followed was a series of phone calls, telexes, and letters between Kubrick and myself and between me and the Angenieux Corporation, who were, in fact, the suppliers of the basic zoom components for all of these 20-to-1 zoom lenses. Through it all, Kubrick displayed the kind of technical knowledge and skill, rare in modern filmmakers, that enabled him to define the problem precisely and specify what had to be done to achieve the lens he wanted.

We went ahead with his program and were just able to put together a working prototype, still not properly finished or calibrated, so, that Kubrick would have it in time for the filming. Again he was delighted with the results, as seen in a number of exterior sequences in the film. We subsequently completed the design of this lens — the Cine-Pro T9 24-480mm zoom — and have built and sold several of these lenses. (And now that Kubrick has finished shooting the picture, we have finally completed the construction of his prototype lens.)

My relationship with Stanley Kubrick has been one of the most unusual, yet intellectually stimulating, that I have ever known. We have spent countless hours in telephone conversations, and written literally hundreds of letters and telexes back and forth. Yet I have never met the man! I felt sure I would while in London attending the Film ’73 exhibition with my wife, Lou. We were escorted to his combination home and office by his executive producer, Jan Harlan. But when we arrived, Kubrick was out scouting locations for Barry Lyndon and expressed his regrets at not having been there to meet us. We were, however, very graciously entertained by his lovely wife, Christiane, who is an accomplished and recognized artist in her own right.

This minor frustration aside, it has been an exciting and stimulating experience working with a man of Kubrick's consummate skills and talents on his recent film projects. He currently has me investigating another camera/optical scheme he has in mind which I think I should keep confidential until he has had a chance to use it. Undoubtedly, it will be used on his next film project (a project which I look forward to with a mixture of trepidation and excitement).

Our company motto is: "Technology in the Service of Creativity." I cannot think of a more fitting example of our motto at work than the modest role my company and I played in the making of Barry Lyndon.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.