Killers of the Flower Moon: Greed, Hubris and Homicide

Rodrigo Prieto, ASC, AMC and Martin Scorsese investigate an infamous murder conspiracy in Osage County.

Photos by Melinda Sue Gordon, SMPSP. All stills and frame captures courtesy of Apple.

Murders committed without conscience are a recurring motif in Martin Scorsese’s films, but the victims in Killers of the Flower Moon are not members of the mob; they are the oil-rich Native Americans of Osage County, Okla., whose enormous wealth — and ethnicity — makes them prime targets for avaricious outsiders. As one character maintains, with callous detachment, “You got a better chance of convicting a guy for kicking a dog than killing an Indian.”

Based on journalist David Grann’s best-selling 2017 nonfiction book Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI, the movie revisits the 1920s, when at least two dozen (and possibly hundreds more) members of the Osage Nation tribe were slain after winning the legal right to profit from oil deposits discovered on their land. “The world’s richest people per capita were becoming the world’s most murdered,” Grann writes.

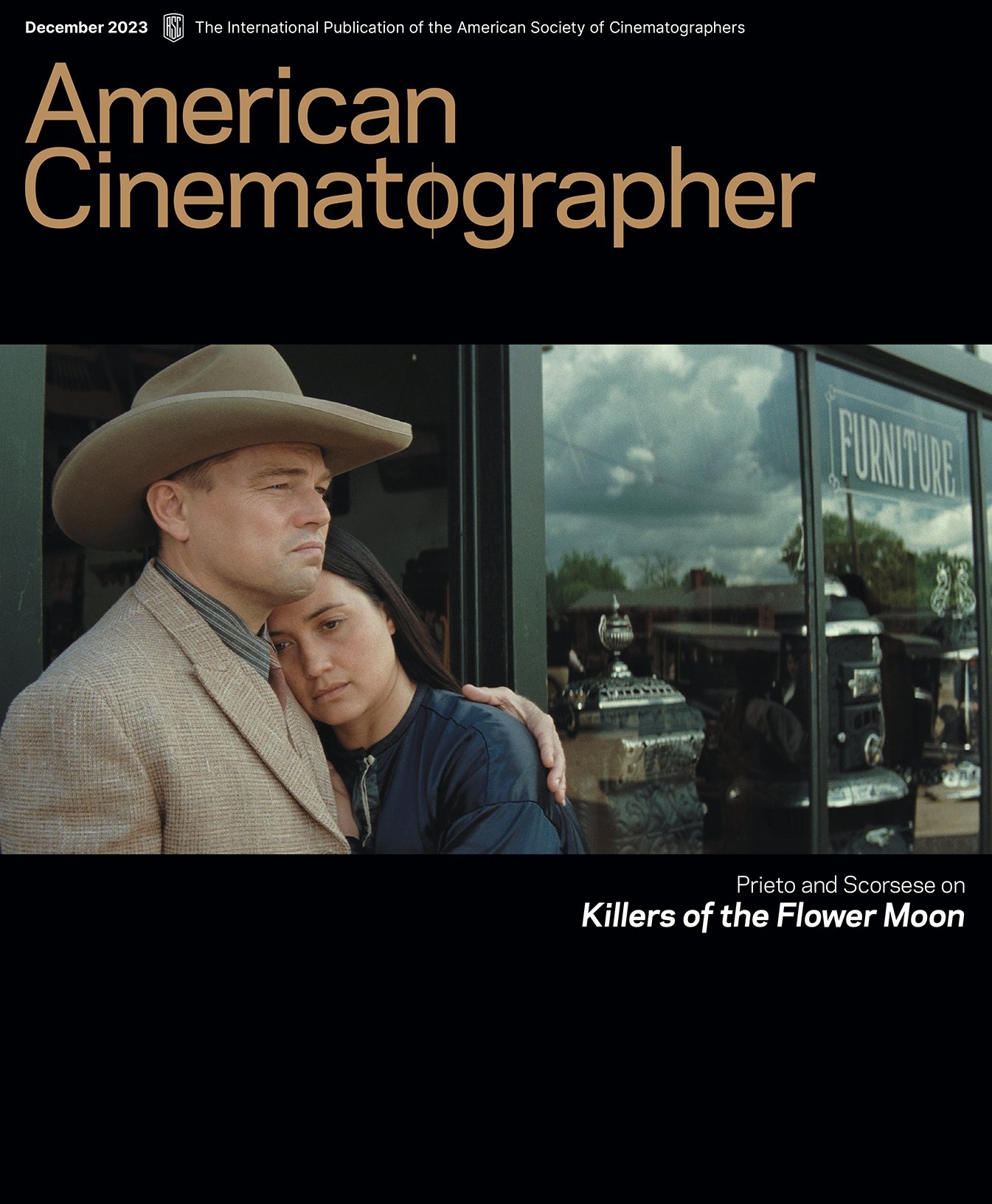

Within this wider scandal, the film’s key figures are cattle baron William Hale (Robert De Niro), known as the King of the Osage Hills, and his nephew, Ernest Burkhart (Leonardo DiCaprio), who marries Osage local Mollie Kyle (Lily Gladstone), with her “headrights” — a share of the immense profits from developers working on tribal land — in his sights. Their schemes are threatened when the U.S. government, responding to desperate outreach from the Osage, dispatches agents of the Bureau of Investigation (which later became the FBI) to smoke out the perpetrators. They’re led by Tom White (Jesse Plemons), an impassive, Stetson-hatted veteran of the Texas Rangers who brings a methodical resolve to the hunt.

A Narrative Pivot, Mid-Prep

Scorsese reteamed with cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto, ASC, AMC to bring viewers into the culture of the Osage Nation and immerse them in the period’s ambience. However, Prieto notes that the filmmakers’ “process of discovery” took place over an unusually extended period that was disrupted both by the Covid-19 pandemic and Scorsese’s reevaluation of the film’s narrative focus. (Production was initially expected to begin in early 2018, but principal photography ultimately took place between the spring and fall of 2021.) The director, who adapted Grann’s book with screenwriter Eric Roth, ultimately settled on a revised story structure that foregrounded the Osage protagonists rather than the FBI’s efforts, which became a subplot introduced later in the tale.

Prieto says he felt the first stirrings of this change around the winter of 2019, some months after he and Scorsese had met with members of the Gray Horse Osage community at a dinner the tribe arranged in their honor. More than 100 Osage attended, and many spoke about family members who had been murdered during the Reign of Terror, as that historical period came to be known. Prieto recalls, “I was sitting next to some pretty important members of the Osage community, including one of the chiefs, and it was just a huge honor. They gave us gifts, like blankets that had been made for each of us, and I also received a ceremonial feather. It was a beautiful experience, but some of the Osage also mentioned their concerns about how the story would be told in the movie.

“Later in the year, we were still prepping as planned with the original script, but Marty kept saying, ‘Things are going to change.’ And then he talked to the studio to tell them he wanted to shift the movie’s perspective.”

The Osage provided advisors for the production, and everything the filmmakers learned from them was taken into serious consideration. Prieto notes, “One of our producers, Marianne Bower, has been doing research for Marty’s films for years, and she went really deep on this one, exploring Osage cultural traditions, the historical record, everything. For example, some of the dialogue in the courtroom scenes was taken directly from trial transcripts. Even things we learned at the dinner had an impact on the story. One of the people who spoke there talked about how important mothers and grandmothers were within the Osage Nation, which became an important focus in the film.”

Vintage Looks and Shifting Tones

During prep, one of the main discussions Prieto and Scorsese had concerned color. Early on, they pondered whether to use different tints to give the movie a vintage feel, but they ultimately abandoned that plan. Instead, they began assessing early photographic processes like Autochrome and Photochrom, Technicolor, and the more modern process of ENR in order to develop LUTs that would give them the tones they desired. Prieto worked closely with senior colorist Yvan Lucas at Company 3 to refine the film’s looks.

Prieto explains, “We created the LUTs during prep, and their importance during production was to make sure the dailies had a look as close as possible to the final DI. When we shot on film negative, we could not monitor on set with the LUTs, but the dailies would have the LUTs we needed for each scene; we were only able to see the LUTs on set when we used the Sony Venice. I sent general timing notes to our dailies colorist.

“To me, in the language of cinema, a film negative with a film print is natural color — which is why we decided to shoot primarily on motion-picture film, which I feel has deeper color depth,” Prieto adds. “It was important for us to accurately represent the colors of the Osage wardrobe and the colors of nature. And then we wanted to differentiate that look from how we presented Hale, Ernest Burkhart and the other descendants of the original European settlers.”

To that end, Prieto began researching early color photography and showing Scorsese examples. The pair found themselves drawn to the look produced by Autochrome, an early color technique developed for still photography by the Lumière brothers, which they first marketed in 1907 and manufactured until 1933. Autochrome is a positive color transparency on glass that’s made by coating a glass plate with a sticky varnish and dusting it with a layer of randomly distributed, translucent grains of potato starch and a coating of panchromatic photographic emulsion. “These grains of dyed potato starch act as filters that allow certain frequencies to pass,” Prieto explains. “The colors Autochrome produces are not exactly red-green-blue primaries — the green is green, but the blue leans more toward violet and the red is more of an orangey-red hue. There’s also a layer of silver halide. The look it creates can be very random, but by studying many Autochromes, we came up with a lookup table that we felt would mimic [the general palette of] Autochrome.”

Mingled with this look were the qualities of another early photographic process called Photochrom, which produced colorized images from a black-and-white negative via the direct photographic transfer of the negative onto lithographic printing plates and hand coloring by the photographer. “The look of Photochrom is much more difficult to reproduce,” Prieto notes, “so [the resulting LUT] combines the feel I got from the Autochrome images I’d researched with my impressions of the Photochrom images.” In the film, early examples of this look can be seen when Ernest first arrives in Fairfax by train and then meets with Hale.

Later, when the horrors of the murder spree take full hold after a house is blown up with dynamite, Prieto shifted to the harsher look of a LUT that emulated the tones of ENR, a color-positive developing technique that uses an additional black-and-white developing bath to retain the silver that is normally washed off during print processing. Prieto explains the progression thusly: “Up till the explosion, the Autochrome look is more prevalent — it’s a little desaturated, with a bit of violet in the skies and magenta in the blues, desaturated greens and yellows, and reds that look more orange. For scenes featuring only our Osage characters, we used a ‘normal film’ LUT that reproduces natural colors accurately. When the ENR happens, it’s a more general desaturation of all the colors, with a higher contrast. This change of look was meant to enhance the feelings of desperation the characters are experiencing as the story unfolds.”

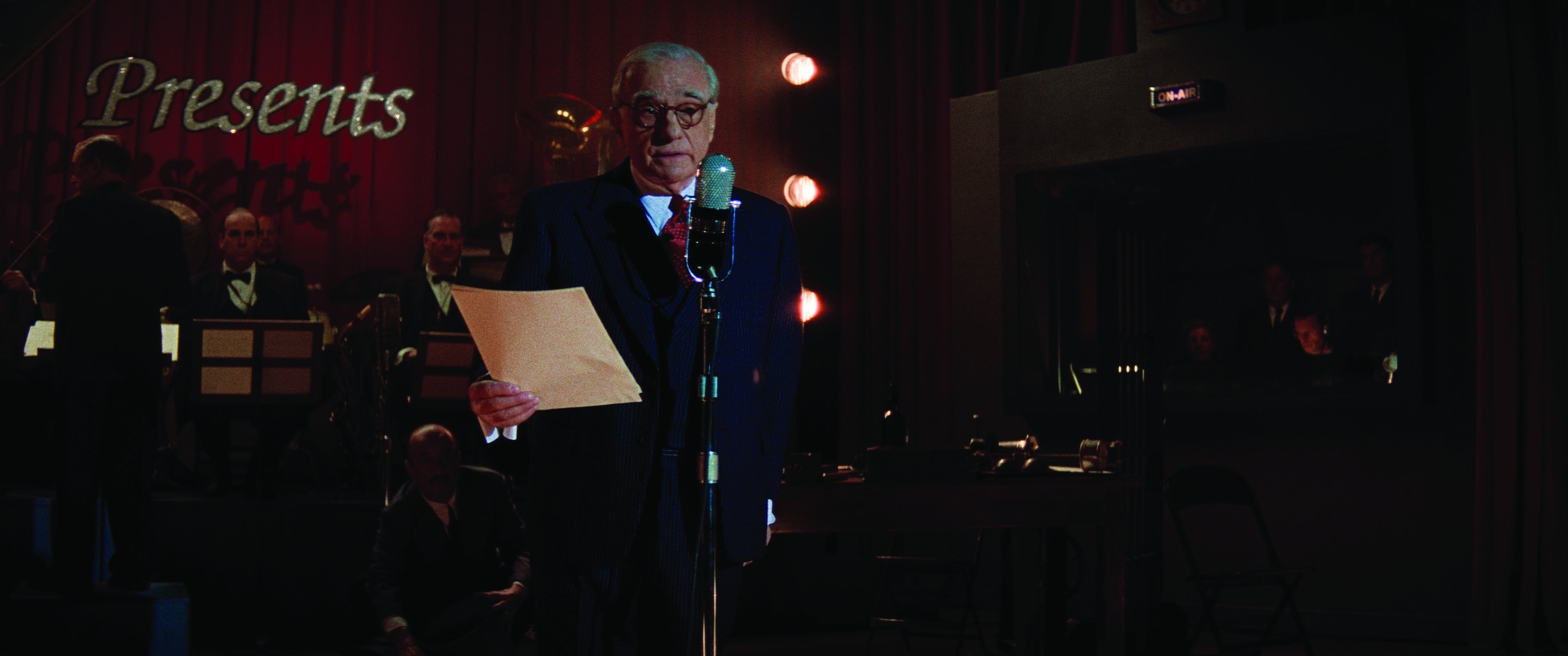

Other LUTs also came into play: a day-for-night LUT was used for the sequences in which Charlie Whitehorn (Anthony J. Harvey) and Mollie’s sister Anna (Cara Jade Myers) are murdered, and a three-strip Technicolor LUT was applied to the moment when Mollie’s mother dies and is led off to the afterlife, as well as the movie’s coda — in which Scorsese makes a cameo as a radio announcer leading a cast of actors during a live broadcast about the killings staged years later, in front of a live audience, who listen as the tragedy of the Osage is presented for their entertainment.

Modern Cameras and a Classic Antique

Prieto’s cameras on the show included Arricam STs and LTs, Sony’s Venice for dusk scenes and night exteriors, and both a Phantom camera and an Arriflex 435 for the high-speed “oil dance“ that opens the film, when a group of Osage are shown rejoicing as a geyser erupts from the ground. “The tight shot of the Osage dancing was done with the Phantom at about 700 frames per second, but the wider shots were done with the Arri 435 at 150 frames per second, because we didn’t want those shots to be quite as slow,” Prieto says. “Of course, the geyser is totally unrealistic, because when oil comes out of the ground on its own, it just bubbles up; it doesn’t shoot out of the ground unless you’re using an oil rig to pump it out! But Marty was aware of that — he just wanted this effect of ‘black rain’ falling on the Osage in a more symbolic way.”

Prieto’s main color film stock on the project was Kodak Vision3 250D 5207 for day scenes, but he also used 50D 5203 (mainly applied to scenes showing Osage rituals, for the clarity of its grain). 500T 5219 was used for tungsten-lit interiors and some night exteriors.

The movie’s simulated newsreel footage was shot with Scorsese’s own 1917 Bell & Howell 2709 camera and Kodak’s black-and-white Eastman Double-X 5222 film stock. “You can try to emulate that kind of look with visual effects, but it’s certainly not the same,” Prieto maintains. “The edges of the frame are the actual aperture of the camera, in the 1.33:1 ratio, and you can see all the defects. Our extraordinary A-camera 1st AC, Trevor Loomis, hand-cranked the camera, and he somehow managed to keep it very close to 24 frames per second. Panavision oiled up the camera for us, and they helped us align the eyepiece to the lenses to compensate for the parallax of the non-reflex camera.”

Prieto adds, “The very first shot of the oil coming up from the ground was actually done as a special effect, using color negative in the Bell & Howell, because we were initially planning to convert it to black-and-white to make it look like newsreel footage. But Marty decided he wanted to use it as color footage in the 2.39:1 aspect ratio, so you’ll notice that the shot jiggles and flickers a bit. Somehow, it works, though — it has this kind of vibration that’s oddly compelling. Marty sometimes just allows these ‘mistakes’ or anomalies to stay in the movie because they have an interesting look or an emotional purpose.

Format and Lenses

Oklahoma’s abundance of flat, open landscapes led the filmmakers to choose the widescreen anamorphic format. “On Brokeback Mountain, I shot in 1.85:1 because we were going for the height of the mountains. But here, with the wide-open landscapes, we were trying to incorporate as much of the land as possible on the sides of the frame.”

Prieto’s primary lenses were Panavision T Series, specially tuned and customized by the company’s senior vice president of optical engineering and lens strategy, ASC associate Dan Sasaki. The cinematographer offers, “I had really liked the T Series when I’d done previous tests with [A-camera and Steadicam operator] Scott Sakamoto, and Dan provided a special set for us. The flares in our set were a little different; they were warmer than the typical ‘anamorphic blue flare,’ which helped us in creating the feel of the story’s era. I should mention that those lenses were not something I specifically requested from Dan; he knew about our project, and he’d had these lenses made and then offered to show them to us!”

Shots captured with the lenses at dawn — when the Osage typically offer prayers as the sun rises to start the day — show off the flare characteristics exceptionally well. Another fine example is a striking, low-angle image of an Osage spiritual leader at a funeral, waving a ceremonial feather toward camera as the sun behind him creates a rhythmic pattern of lens pings. “We had to do that scene at noon, because that’s when the Osage bury their people,” Prieto notes. “It’s a very specific thing, and Marty would not have settled for any other way. So, the shot had to be timed very precisely with the position of the sun. Normally you’d avoid shooting at that unflattering time of day, but we tried to do the entire scene with the sun overhead. The presence and position of the sun is very important in Osage culture, and we felt it was important to represent that accurately.

The filmmakers also used a customized set of anamorphic Petzval lenses for shots of murdered Osage characters. “Marty wanted to show the results of these killings in a dispassionate manner,” Prieto says. “He didn’t want to make them extra-dramatic. So, most of those shots of the victims are very simple overhead angles on the bodies, but the Petzvals create a kind of soft-focus vignetting around the edges that gives you this certain feeling about all those deaths — the effect is a bit unsettling.”

Aiming for Authenticity and Naturalism

Thanks to Scorsese’s respectful interactions with the Osage, the production was able to obtain permission to shoot on the tribe’s reservation in Oklahoma, at many of the actual sites where the murders had occurred a century earlier. The town of Fairfax is shown during sequences set in the neighborhood Mollie and Ernest move into; other authentic locations include the office occupied by doctors James and David Shoun [Steve Witting and Steve Routman], and a Masonic lodge.

To ensure further accuracy, a number of Osage artisans and craftspeople were hired to work on the show in various capacities, helping with production design, wardrobe, cultural consultations and linguistics, among other areas.

Prieto offers, “Our visual strategy was primarily based on the material, and the Osage themselves — we wanted to just draw from what we learned and try to connect emotionally with that information, and with each of the characters. First and foremost, we wanted to photograph the Osage as naturally as possible in their world and their specific environments.”

Production designer Jack Fisk — whose credits include work for directors Terrence Malick, David Lynch, Paul Thomas Anderson and Alejandro González Iñárritu — constructed the show’s sets, either by repurposing existing structures or building new ones from scratch, the latter including Hale’s ranch house and Mollie’s home. The main street in Pawhuska — a town that doubled as Fairfax for significant portions of the film — was redressed for the period, and Fisk and his crew also built a train station nearby on a square mile of land that the Osage Nation had recently purchased.

In general, Prieto’s strategy for interior sets was to allow light from outside windows to travel deep into the rooms so Scorsese could block the actors’ movements any way he wanted, without requiring the performers to be close to windows. Prieto’s approach was inspired by the naturalism he admired in the work of cinematographers like Sven Nykvist, ASC, FSF, and particularly Néstor Almendros, ASC. “For daytime scenes, I really tried to use the windows as light sources,” Prieto says. “We used 18K Fresnels on condors to simulate sunlight coming through some windows, but we also used 18K Fresnels and Arrimaxes going through 12 by 12 frames with very dense Magic Cloth diffusion on them for soft ambient daylight also entering through windows. Many times, the ceilings and windows were high, so we added these strips of bright hybrid LEDs — 2,700 to 6,000K — comprising diffused LED fixtures packed with LED tape from LiteGear that would also carry some light into the room from the angle of the windows. The hybrids are tungsten and daylight-balanced LEDs that you can mix to achieve different color temperatures; for daylight scenes we used them at 5,600K.

“Another thing we used for most of our interior settings were soft boxes rigged to the ceilings, with hybrid LEDs coming through Magic Cloth diffusion. Then we would skirt them or put Lighttools Soft Egg Crates on them to create a toplight; I mostly did that for night scenes to emulate the look of overhead lamps and lightbulbs.”

The value of this strategy is most apparent in an impressive Steadicam shot operated by Sakamoto, who guides the viewer from room to room during a family gathering at the ranch house where Mollie and her mother live, with various characters moving through frame. “We had to be very, very careful in placing the lights outside the windows so the camera wouldn’t see them,” Prieto says. “I helped the shot by placing those soft boxes overhead, at a low fill level so they wouldn’t feel like a source — they just created some ambience. We had to be ready to shoot in any direction, so those soft boxes really helped. They were hybrid LEDs, and for that long shot we used daylight color balance. I also used those units on the ceiling of the doctors’ office, and for some of the scenes at Hale’s ranch house as well.

Contrasting Environments

Prieto and Scorsese took pains to show the contrast between the lifestyle and environments of the Osage and non-Osage characters. In an early scene that establishes the movie’s central conflict, the Osage are shown meeting with tribal leaders to discuss the ongoing rash of murders. The sequence is set in a “bark lodge,” an oval structure built from wooden poles stuck in the ground, bent to form a dome and then tied together before being covered with sheets of tree bark, animal hides or canvas. Production designer Fisk told Prieto that there was a gap at the top, used by the Osage to let smoke from cooking escape the structure, that he could light through. “So, the lighting strategy was dictated by the set, but I also wanted to work from the concept of bringing nature into their spiritual gathering in the form of the sun,” Prieto says. “I felt it was appropriate to bring a big shaft of ‘sunlight’ in through the roof and just bounce it off the ground to light everyone’s faces.

“Our amazing gaffer, Ian Kincaid, helped achieve that. There are not many HMI lighting units you can point straight down. Ian thought we needed an 18K Arrimax, but again, you can’t really tilt an Arrimax like that. So, he and the grips created this rig that allowed them to position the Arrimax horizontally on a condor lift while shining it into a mirror that was set at a 45-degree angle.”

Throughout the film, the Osage are shown in natural exterior settings or in homes that have a warmer, more friendly ambience. The environments occupied by Hale and his associates often stand in stark contrast, especially during a scene set in a former Masonic lodge space (refurbished by Fisk), where the uncle and Ernest’s brother Byron (Scott Shepherd) meet with Ernest to discipline him for making an unauthorized side deal. The room has a very severe atmosphere, complete with high ceilings and a section of flooring with a stark, black-and-white checkerboard pattern. After instructing Ernest to bend over and brace himself against a podium, Hale wields a heavy wooden paddle and gives his nephew several agonizing smacks on the backside. Prieto explains, “In his research, Jack Fisk noticed Masonic halls with a checkered floor, and Marty liked the look. The space we were in had these two skylights, which had been covered by a new roof at some point. Between that cement roof and the glass skylight, we fit in a bunch of LED units, adding some diffusion to them. But there was only about 2 feet of space for that.”

In one striking close-up, the checkerboard floor is reflected in Hale’s glasses, giving him the stern look of a taskmaster disciplining his pupil. “Those glasses were hell for me, because everything was reflected in them,” Prieto recalls. “A lot of my lighting design for Robert De Niro in that scene depended on us not allowing the lighting units to be reflected in Hale’s glasses, so I had the grip department build two big frames with Magic Cloth and checkered patterns on them similar to the floor’s. We could then light through them to provide fill light, and if Hale’s eyeglasses reflected the frames, it would look like it was the reflection of the floor!”

A brooding tone also prevails in some of the scenes at Hale’s house, with its walls of dark wood. While researching homes of the era, Fisk learned that dark walls were fairly common; Prieto found this convenient because it allowed him to control the levels of brightness on the walls, and also convey the dark natures of Hale and his accomplices. In one key sequence late in the movie, Ernest comes back from a court appearance and joins a gathering in Hale’s den, where he’s confronted by townsfolk and his uncle’s infuriated lawyer, W.S. Hamilton (Brendan Fraser), who bellows at Ernest about his forthcoming testimony. “I wanted all of these characters to feel almost like marble statues, in complete contrast to how it feels when you’re among the Osage people,” Prieto says. “Even after we progress to the ENR LUT, Mollie’s house and the other Osage homes have a warmth in the lighting, but I wanted the scene in Hale’s den to feel very cold — even though the scene’s lightbulbs are low-wattage, which usually give off a warmer look. But I planned all along to color-time that scene to be cold and very contrasty, with the character’s faces emerging from this very dark background to create a chiaroscuro effect. To achieve that look, the soft boxes we were using above the actors needed to be very controlled; I used them to add a soft but menacing toplight, in the style of The Godfather. Sometimes I used our Soft Egg Crates on the boxes, and sometimes I would use skirting to control the amount of light on the backgrounds.”

Fire Drills

Several key sequences in the film feature fire gags that augment the drama in both subtle and spectacular fashion.

In one of the earliest scenes, Hale meets with Ernest in his home’s study, where the two sit down for a fireside chat that allows the uncle to assess his nephew’s potential as an ally. “Fire became an important element in the film,” Prieto says. “To my mind, the fire in the film has almost a biblical aspect, perhaps representing Hell. Hale’s name even sounds like ‘Hell,’ as in ‘Hell is coming.’ So, we played off that a bit. I intuitively wanted to use fire for the scene where Hale and Ernest have their talk, and also for a later scene when the drunken body of Henry Roan [William Belleau] is laid out in front of the fireplace.

“Since Hale’s house was a set built on location, I asked Jack [Fisk] to keep that fireplace open so we could bring lighting through the back. I used a combination of Astera tubes with a fire effect on them, and some MR16s, which have more directionality and punch. Then we shot a plate of real fire for the visual-effects team, which is what you actually see in the fireplace. So, the flames are a visual effect, but it looks as if the firelight is actually lighting the whole room.

Later in the film, a much larger fire gag was employed to create a visually stunning sequence that occurs when Hale decides to burn the land around his ranch to collect insurance money. Prieto reveals, “The script only called for a shot of Hale at his house, watching the burn, with the FBI agents just seeing this glow in the distance as they have their secret meeting at the oil rigs. But Marty turned it into a much bigger thing. To accomplish what he wanted, the special-effects team had to dig trenches in very specific places around the house and then install big gas pipes. Behind the house, I placed some Dinos with flicker effects that would light up the smoke effect to silhouette the house. I then asked the effects team to place some smaller pipes very close to the camera lens to create a bit of distortion. We used three cameras in all; the main camera was capturing a wide shot of the fire, and the others were on long lenses.”

Onscreen, the result of these efforts is a mesmerizing tableau that shows workers trying to get the fire under control, as oddly moving silhouettes amid waves of distortion that create the feel of a surreal, undulating hellscape. “We didn’t really anticipate how unusual the effect would look when we were planning it,” Prieto says. “Of course, I know very well that you’ll get a bit of distortion if you shoot through the waves of heat coming off a pipe placed directly under the lens. You don’t photograph the fire itself; you just get the effect of the heat waves. But there was a fire effect set up in the middle distance, with a much larger gas pipe, maybe 50 feet from us. And that is what caused that big distortion — it was a combination of the foreground heat waves from the small pipe plus the waves that were generated from the much larger pipe farther away.”

Other large fire pipes were deployed behind the stunt people involved in the scene — who were also dancers, directed on how to move by Scorsese and a choreographer, resulting in an eerie “dance of death” milieu. Prieto adds, “There are some shots of Hale and Ernest looking at the fire, and we did those with a small fire bar placed just below the lens to add a bit of distortion. I lit them with a couple of 5Ks through various shades of orange gels, using a 12-by-12 frame of silver lamé to create some movement on their faces. If you look closely at Leo’s eyes in the tight shots on him, it looks as if there’s fire in them, but it was really just the silver lamé that we were shaking offscreen.”

The Law Intervenes

After the Bureau of Investigation gets involved in the case, agents arrive in Fairfax to question the townsfolk, and begin to close in on the culprits. Ernest and Hale quickly become prime suspects, and both are detained.

Soon, Ernest is cornered and must testify in court — where he faces the stony glare of his uncle, who’s been imprisoned in the town jail. The courtroom and jail sets were built in a church by Fisk, with the former set located on the ground floor and the jail constructed in the basement. “Because it was a real location, we faced some heavy-duty limitations,” Prieto says. “I really wanted to have Ernest in very harsh sunlight. I wanted him to be in the spotlight, with nowhere to hide, and I wanted the audience to feel his discomfort.”

Although the church presented limited opportunities for windows, Fisk was able to assist with Prieto’s plan by installing fake windows on the side of the courtroom that faced the camera for certain shots; an upstairs gallery on the same side allowed him to build additional fake windows for sunlight effects. “Coming through those lower windows, we had Arri SkyPanel S60s aimed through diffusion. For each of the upper windows, we had an Arri S360-C paired with HES Solaframe 3000 Hi-Fi robotic moving lights. That way, I could decide where the ‘sun’ would be for different scenes just by controlling the direction and size of the beam remotely. It might have helped if the walls had been dark, but Jack insisted that in that kind of place, historically, the walls would have been white. So, I went all the way with that to create that feel of blinding light throughout the space.”

The basement jail set built at the same church was lit to have the gloomy look of a dungeon. Fisk built the cages based on his research — and to provide appropriate ambience, Prieto and his crew lit the space with China hats with 300-watt mushroom bulbs in them. “The toplight those bulbs provided was very directional and contrasty,” Prieto says. “We lit everything in the cells with those practicals, and we would just tilt them in the appropriate direction. Ian had these weighted magnets he would put on the fixtures to make them tilt in whatever direction we needed. The lighting that resulted from our strategy was super harsh, and it made the actors’ eyes just go black. For the climactic dialogue between Ernest and Hale, through the bars of a cell, we shot with two cameras, and I had to add a bit of eyelight for each actor with these pencil-thin, diffused, battery-powered LiteGear LED sticks. Those were put in front of each off-camera actor, below the frame, to light the other person. The tricky part was avoiding the shadows of the bars so the audience wouldn’t notice the eyelights!”

Coda

In reflecting upon the filmmakers’ philosophical approach to the movie, Prieto points out that the strategies he and Scorsese employed are designed to reflect various ways in which the tragic Osage saga has been represented. “It’s about how stories are told,” he says, “from the newsreel footage through the other looks we created.”

He notes that the finale featuring the radio broadcast “was not in the original script, but was added to show one of the ways the story might have been presented by white people.”

As the broadcast makes abundantly clear, justice was only spottily served in the aftermath of the Osage killings. An Osage chief quoted in Grann’s book sums up his tribe’s tragic collision with history: “Someday this oil will go and there will be no more fat checks every few months from the Great White Father. There’ll be no fine motorcars and new clothes. Then I know my people will be happier.”

Tech Specs

2.39:1

Cameras | Arricam ST, LT; Arriflex 435; Sony Venice; Phantom Flex4K; Bell & Howell 2709

Lenses | Panavision T Series (custom), V Series, anamorphic zooms, Petzval anamorphic

Film stocks | Kodak Vision3 500T 5219, 250D 5207, 50D 5203, Eastman Double-X 5222