Ocean’s Eleven: Smooth Operators

Steven Soderbergh doubles down as both director and cinematographer on Warner Bros.’ high-stakes heist remake.

Unit photography by Bob Marshak

Occasionally awkward in the acting department and implausibly plotted to boot, the 1960 film Oceans 11 could have disappeared into the annals of undistinguished cinematic history. But the heavyweight cast alone lifted this lightweight film above mediocrity and into the upper echelons of coolness. And frankly, it didn’t hurt that the film trumpeted the fact that, for the first time, those charismatic crooners and consummate entertainers known as the Rat Pack were on the big screen together.

Directed by Lewis Milestone and photographed by William H. Daniels, ASC, the film starred Frank Sinatra as the hip Danny Ocean, who enlists Sam (Dean Martin), Josh (Sammy Davis Jr.), Jimmy (Peter Lawford), Mushy (Joey Bishop) and five other war cronies to help him rob five Las Vegas casinos at the same time — only to have the spoils go up in smoke, literally. Today, their seemingly impossible heist looks all too easy to accomplish since The Strip doesn’t operate in such outdated fashion anymore.

Time for a high-tech update. After rounding up enough scratch to set the production’s roulette wheels in motion, Warner Bros, and producer Jerry Weintraub welcomed Steven Soderbergh into the game to direct screenwriter Ted Griffin’s modern take on the subject matter. Though very different in style, the 2001 Oceans Eleven has a few things in common with the 1960 version. The basic premise remains the same, Las Vegas is still the focal point, and a star-powered ensemble cast is on board.

“At this point in my career, I have a really difficult time sitting through the first four films I made. I find them too controlled, too formal, too thought-out. They don’t have any energy to me. I think I was being too precious about the wrong stuff.”

— Steven Soderbergh

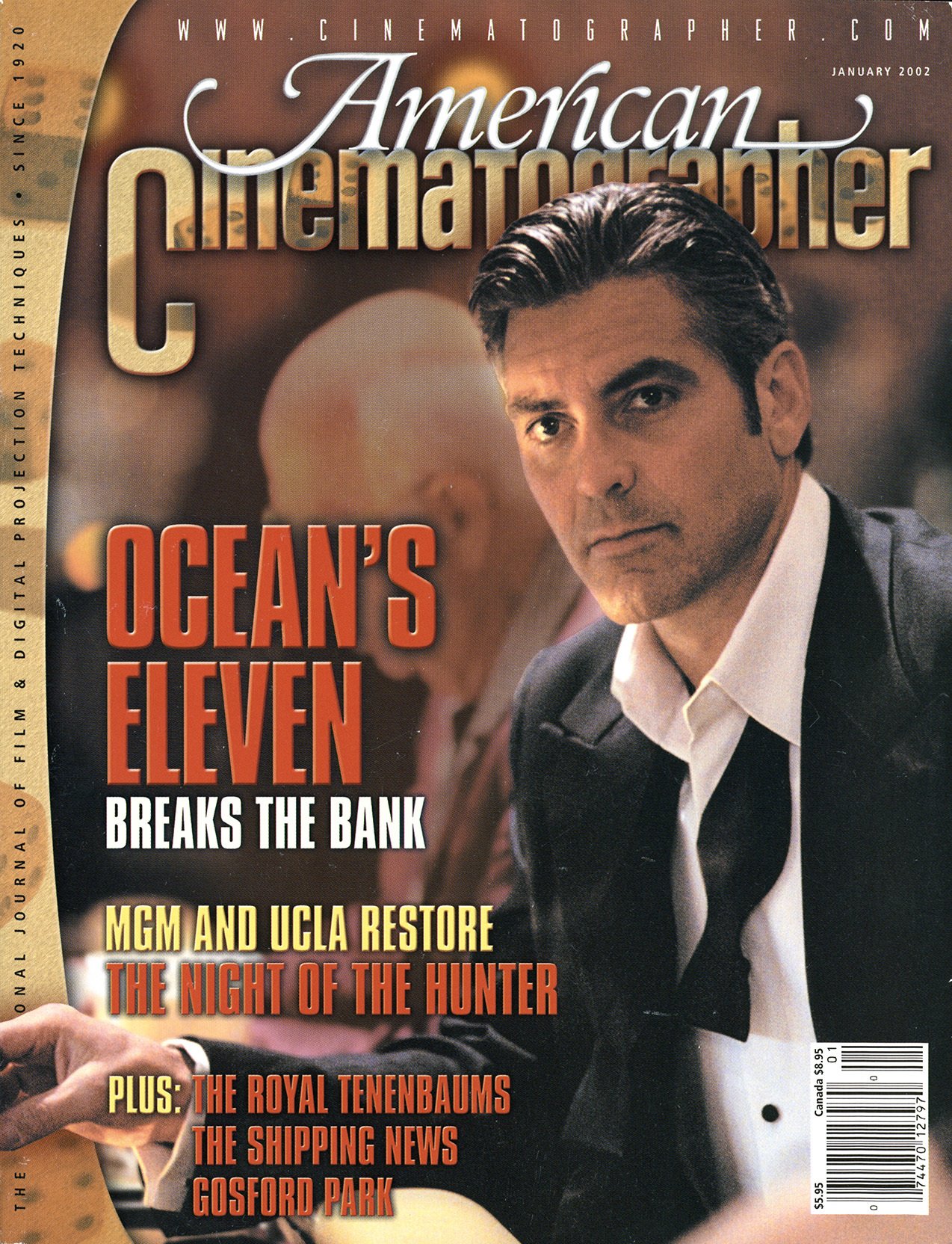

The new Oceans Eleven stars George Clooney as career thief Danny Ocean, who has just been paroled. Terry Benedict (Andy Garcia), owner of the Bellagio, Mirage and MGM Grand hotel/casinos in Las Vegas, possesses two things Danny really wants: $160 million and Danny’s ex-wife Tess (Julia Roberts). Naturally, the first thing Danny does once he’s out of prison is to violate parole by traveling around the country recruiting 10 of his con-artist and grifter friends for an audacious mission to stick it to the hotel-and-casino magnate. The gang includes cool and collected details man Rusty Ryan (Brad Pitt); master pickpocket Linus Caldwell (Matt Damon); bankroller and Benedict-hater Reuben Tishkkoff (Elliott Gould); Cockney munitions expert Basher (Don Cheadle); uptight surveillance expert Livingston Dell (Eddie Jemison); ace card dealer Frank Catton (Bernie Mac); retired flimflam man Saul Bloom (Carl Reiner); the bickering Malloy brothers, Virgil (Casey Affleck) and Turk (Scott Caan); and the acrobatic grease man Yen (Shaobo Qin). With careful planning and misdirection, the con artists conspire to clean out the central vault during the Lennox Lewis-Wladimir Klitschko heavyweight boxing match. And Danny will make every attempt to win back Tess during the ensuing chaos.

For Soderbergh, 2000 was a very good year. He became the only director to have two films, Erin Brockovich and Traffic, nominated for Academy Awards for Best Picture and Best Director in the same year. He won the directing Oscar for Traffic, the first time in 72 years that a director had successfully competed against himself. Another unique aspect of his triumph is that Soderbergh was pulling double duty on Traffic, also serving as director of photography, but under a pseudonym.

“I don’t think this should be a trend. I was trained as a still photographer. I’ve been shooting since I was 13, and I’ve worked with really terrific cinematographers whom I’ve bombarded with questions and watched very closely in order to learn [the craft].

Soderbergh had served as his own cinematographer before, mostly early in his career, on short films and on the quirky 1996 feature Schizopolis, in which he also starred. But Traffic marked a conscious change in his working style; its guerilla technique was an outgrowth of the realistic, rough-edged style displayed in Soderbergh’s 1999 film The Limey, which was shot by Edward Lachman, ASC (see AC Nov. ’99). With Traffic, Soderbergh melded the positions of director, cinematographer and camera operator into one

“I feel I’ve closed the gap between myself and what I want to accomplish to the greatest degree possible,” Soderbergh says. “For me, it’s a good way to work, and I think it helps the work, even though it adds a level of performance anxiety to do all of those jobs.”

This method has allowed Soderbergh to be more intimately involved with the material — an ironic twist for someone who has relaxed what he calls his “death grip” on his films. “At this point in my career, I have a really difficult time sitting through the first four films I made,” he says. “I find them too controlled, too formal, too thought-out. They don’t have any energy to me. I think I was being too precious about the wrong stuff. It took me a while to find my equilibrium. I feel more comfortable now than I did 11 or 12 years ago, and I have a different set of priorities.

“It’s become a very organic process for me,” he says of directing and shooting. “It’s really about creating the canvas piece by piece, and I’m willing to reconcile the fact that I’m not a world-class cinematographer for the momentum. Working this way is as close to writing with a camera as I can get, literally. I think now it would be difficult for me to insert another person into that process.”

Having a combo director cinematographer on a project is very common in the commercial and documentary realms, but rare in the world of features. A few cinematogaphers have lit a scene and then taken a seat in a director’s chair. Luciano Tovoli, ASC, AIC, did so in 1982 for II Generale delTarmata morte (The General of the Dead Army). John Alonzo, ASC directed and shot three telefilms, Champions: A Love Story and Portrait of a Stripper in 1979 and Belle Starr in 1980. Even Gregg Toland, ASC pulled double duty once for the feature-length documentary December 7th (1943), which he co-directed with John Ford. However, one would be hard-pressed to find a feature director who has added cinematographic duties to his responsibilities. One is director Peter Hyams, who has been shooting his own movies for many years.

“I don’t think this should be a trend,” Soderbergh concedes. “I was trained as a still photographer. I’ve been shooting since I was 13, and I’ve worked with really terrific cinematographers whom I’ve bombarded with questions and watched very closely in order to learn [the craft]. When I decided that I was going to try it, I thought about it at length. It’s not something I take lightly. I’ve just found a way of working that feels very comfortable for me; it has more to do with getting to what I consider to be the right set of solutions for a given problem as quickly as possible, and increasing the intimacy [I have] with both the actors and the film itself.

“The lighting was very reality-based. First we looked at what the reality was, and then we tried to make it work. We may have needed to enhance a few things for dramatic purposes or just to get an exposure, but we wanted the movie to look as if it wasn’t lit at all.”

— gaffer James Plannette

“Part of what I do in my spare time is study,” he says in regard to the continual learning process that defines the art of cinematography. “I read AC. I watch very closely what other cinematographers do, and I borrow all the time. I’m sure I’m not alone in tracking the people I respect, making sure I see everything they do more than once to get a sense of how they accomplish the various effects they employ.”

Soderbergh, who did some camera operating on both The Limey and Erin Brockovich, joined the Local 600 union as a director of photography to shoot Traffic. The pseudonym came into play because the Writers Guild wouldn’t allow him to take the credit of “Directed and Photographed by” for the film, and he didn’t feel comfortable having his name in the billing block twice. Local 600 granted him permission to use the pseudonym Peter Andrews, a moniker that combined his father’s first and middle names. “It was a great way to pay tribute to my dad, who’s not around anymore and is the person who gave me the film bug,” he says. “Ironically, the Writers Guild was willing to allow me to combine the [director-photographer] credit on Oceans. But I thought it was good karma to leave it the way it was.”

For a while following the release of Traffic, Soderbergh was rather mum about the cinematographic aspects of his work. “I wanted to be very careful not to make it seem like this was something I took lightly, or make it out to seem like anything that unusual. I wasn’t interested in waving a flag about, and I’m still not. But at the same time, I want to share information. That’s what this magazine is about. I’m somebody who believes in giving anyone who cares to listen the benefit of whatever experience I’ve had.”

For Oceans Eleven, Soderbergh re-teamed with his ace gaffer from Traffic, James Plannette, a 29-year lighting veteran who’s gaffed such films such as E.T., Someone to Watch Over Me and Braveheart, among many others. “He’s the perfect combination of experience, enthusiasm and flexibility,” Soderbergh declares. “I need somebody who has ideas when I don’t have any, and who also doesn’t get bent out of shape when I have very specific ideas. He’ll try anything and knows what the effect will be because he’s so grounded in all the photographic technical skills you accrue when you’ve been doing this for decades. Anybody watching us work would see very quickly that we’re linked at the hip

Plannette quips, “Because he’s the cinematographer as well, he does the director’s part, and then he never leaves the set. If we’re headed in the right direction, that’s great. And if we’re not, he’ll say, ‘Maybe this isn’t quite what we want,’ and we’ll change it. It’s a very collaborative effort and a pleasurable experience. He doesn’t have a tremendous amount of experience as a cinematographer, but he has a great eye and great taste. Together we end up in the right place.”

“I spent more time as a cinematographer waiting for the director to figure out what he wanted to do than the other way around,” jokes Soderbergh. “There were days when I was stumped directorially. For the first time on any movie I’ve made, there were elaborate setups that I’d spend an hour and a half or two hours on, only to tear them down before we even shot them. But I was able to figure out the right approach by doing the wrong thing. Once that was done, deciding how to light was usually a quick conversation between Jim and me. Luckily, the crew I work with is so efficient that I had the luxury of starting over and knowing that I’d still make my day.”

Oceans Eleven is composed in a very slick style that

complements the cool characters and their hip hangouts. The filmmakers

received their lighting cues, or vibe, if you will, from the natural

aesthetics of the locations. Soderbergh explains, “When we went on the

tech scouts, which are my least favorite part of filmmaking, we’d show

up, and it was either great and we didn’t want to, as Jim puts it, ‘put

our foot through a Rembrandt,’ meaning we’d shoot it pretty much as was,

or it was not terrific and we’d discuss how to make it feel a little

more organic to our film and what we were trying to do without violating

it. Sometimes it was as simple as adding some color somewhere.”

Plannette elaborates, “The lighting was very reality-based. First we looked at what the reality was, and then we tried to make it work. We may have needed to enhance a few things for dramatic purposes or just to get an exposure, but we wanted the movie to look as if it wasn’t lit at all.”

To get that kind of exposure, Soderbergh placed strong demands on his film stocks, Kodak Vision 500T 5279 and Vision 250D 5246. “We ended up shooting almost all of the film with 5279 pushed two stops but rated at 1200 ASA,” he says. “In a sense, we’re pushing two stops but shooting only a stop and a half over. Even though the movie is designed to be slick and elegant, it doesn’t feel too glossy because it’s got a little bit of grit in it, and I loved the contrast [the stock] gave me. I’m really happy with the way that looks, and it affords you so much flexibility. We tested the 800-speed [5289] as well, and I found that the 79 was sharper. I’m incredibly impressed with how robust the 79 is.”

“In theory, of course,” says Plannette, “if you push 500 two stops you rate it at 2000, but we didn’t feel we were getting a full two stops. The ASA was derived based on getting decent printer lights at the lab. About 95 percent of the 79 is printed at 24- 31-25. We felt that was a good middle-of-the-scale printer light, and we altered our ASA to get that. We had an Eastman Kodak rep at our dailies one day, and when we told him we were pushing two stops he found it hard to believe.”

“At the beginning of each day,” Soderbergh says, “we’d shoot a gray card, and we’d build into the gray card whatever adjustments needed to be made to hit those printer lights. If we were going for a warm look, we’d put lA blue on the gray scale so that it would come back looking a bit warmer. If we wanted the scene to be printed down, we’d shoot the gray scale in a way so that when our printer lights were used, the scene would be down. We tried to take all the guesswork out of it.”

The results are tight grain control, inky blacks, deep shadow detail and bold colors. For the film’s few day sequences, the 5246 was pushed only one stop and had its own set of printer lights. CFI handled all the developing and printing, and Technicolor was responsible for the release prints.

Another key factor in the film’s look is the use of Kodak Vision Premier Color Print Film for all release prints, which for Soderbergh was “possible only because we came in under budget,” he says with a laugh. “After I did some tests involving some other print stocks and other ways of trying to get that look, I went back to Warners and said, ‘It’s just not the same.’ They said, ‘Okay, then we’ll use the leftover production money.’”

Adds Plannette, “It seems to hold the highlights, like the bright street lights and the headlights of cars, and yet dig into the shadows at the same time.”

Because the film was actually picking up a little more detail than was apparent to the eye on set, a trusty Polaroid was used as a reference to gauge the lighting parameters. “We used an old, modified Polaroid 195 that has shutter speeds and f-stops,” explains Plannette. “We used 3000 ASA black-and-white film but rated it at 2400 ASA. Then we just figured the Polaroid was a stop faster than what we were doing [with motion-picture film]. The Polaroids were amazingly accurate. Compared to the Polaroid film, the highlights would hold a little better and it would dig into the shadows a little bit better on the motion picture film, but we took that into consideration.

Color, emboldened by pushing the 5279 two stops, is liberally dappled throughout the film. Says Soderbergh, “Differences between colors in my mind become more apparent when I begin to mix color temperatures, or when I have scenes like those on the casino floor, which are so warm they’re almost monochromatic. Jim and I decided that we weren’t going to back off from the clash of colors.

“For instance, we shot at Musso and Frank’s [restaurant in Los Angeles], where Danny and Rusty Ryan meet. We played up the contrast of colors a little more than you might normally. That reflects our taste in acknowledging that in life, there is a clash of color temperatures. All of the cinematographers I love have always embraced color and used it as a way to enhance mood and drama. We’re always looking for ways to use color to put you inside the world a little more.”

Plannette expands: “We installed practical lights in all of the booths at Musso’s. The fixtures were very yellow, and in an effort to achieve reality we actually used only those lights for the faces with no fill. In the background, we placed a very dim fluorescent in the entryway. We put up a couple of Babies in each direction to separate the actors from the dark background.”

The film was shot in the Super 35 format using the newer Panavision Millennium XL cameras. Sharper Primo lenses were used because of the additional optical printing step associated with Super 35. Soderbergh operated the A-camera while Duane Manwiller operated the B-camera and Steadicam. Soderbergh points out that for Oceans Eleven, he called upon the Steadicam more than ever before. “There’s a lot of movement in the film,” he says. “I would use the Steadicam when I felt I couldn’t get what I wanted from the dolly or couldn’t get the effect I wanted. More often than not it was when I wanted to pan in the opposite direction of my track — going one direction and then pivoting with someone who’s going the opposite direction. If you’re not an accomplished operator, which I’m not [laughs], that can be a difficult move to do well. I would just have Duane do it because he can walk toward the actor, pivot and get the sensation that I couldn’t get on the dolly. Quite often we even put the Steadicam on the dolly or on a Western dolly.”

Because the film features more than 11 key characters in pivotal locations, camera movement was a way to clarify the accomplishment of Danny Ocean’s complex plan. “I’m a huge fan of being geographically clear and making people comfortable with where everyone is and where each is going,” Soderbergh confirms. “In a movie like this, the locations play a huge part in the plot, and I was very interested in showing as much of the environment as I could.”

The film opens with an unshaven Ocean seated in front of some windows at his parole hearing with 3/4 backlight over both shoulders one of the scenes with which Soderbergh wasn’t happy. “It’s the first shot in the movie, and it makes me wince,” he admits. “The edge lights wrapped around too much. I didn’t want them to hit his nose. I wanted to draw a line around George, but because of the shape of the room I was having difficulty placing the light where I wanted and keeping the lamps out of frame. I wasn’t very pleased with it, but I thought George was very good in the scene, and I didn’t want to risk redoing it. Like I said, I’m probably willing to compromise more than most. I know we did knock down the windows and the fan vent with either ND3 or ND6. I think that was one of those days where Jim said, ‘Does it really need to be nine stops over?’ — like it was on Traffic.”

Plannette reveals, “The film holds the highlights so amazingly well that when we stopped down, the windows were probably five stops over yet didn’t give the appearance of blowing.”

After recruiting his crackerjack card-dealing friend Frank Catton in Atlantic City, Ocean heads to Los Angeles to meet up with his right-hand man, Rusty Ryan, at the voyeuristic club Deep in Hollywood. In a back room, a set constructed for the film, Ryan is seated at a round table teaching some young TV personalities how to play high-stakes poker when Ocean joins in.

“The poker game is entirely lit with an overhead fixture that had swivel sockets with MR-16 globes in them,” says Plannette. “The only other light is a [fluorescent] daylight blue tube in the background.”

Adds Soderbergh, “It was behind one of the hanging things on the wall. We then duplicated it with a couple rolling edge lights that we would move according to whatever shot we were doing so we could wash people with it.”

“When we got into tighter shots,” Plannette details, “we had a white card or a Kino Micro Flo on the table to provide a little bit of fill.”

“I love the Mini Flos and Micro Flos,” Soderbergh notes. “We’d lay those on the table if we felt somebody’s eyes were going down too much — put some, as we say, ‘schmutz’ in front of them, put them on a rheostat and just dial them to taste. I mount them on top of lenses all the time, too.”

“There are a lot of things about the film that I really like. Toward the end, all of the guys are standing outside the Bellagio fountains, and it’s very touching when it ends on Carl Reiner as he’s thinking about how it doesn’t get any better than this.”

The crew gathers in Las Vegas and begins carrying out the caper. Whereas all sequences that take place outside of Vegas were shot cleanly, everything in Vegas, both indoors and out, was photographed using Tiffen Black Pro-Mist filters — ¼ for the interiors and ½ for the exteriors.

“I was trying to figure out how to do the big dialogue scenes, where everybody was either standing or sitting around, in a visually interesting way,” Soderbergh says. “You’ve got a lot of people in a fairly confined space. I wasn’t worried that it couldn’t play, but I didn’t want it to be boring. The scene where Danny tells everybody the plan at Reuben Tishkkoff’s house in Las Vegas was really my first exposure to that. That was the scene where I discovered the glory of the 27mm; the entire scene is shot on that lens. I just tried to frame shots that clearly established where everyone was, where they had enough depth and geometry to them to make them interesting to look at.”

While everyone surveys the targeted establishment, Ocean inevitably meets up with Tess at a Bellagio restaurant. Lighting in the casino principally has a very warm, wrapping quality. “In a normal key situation, I’m always bouncing or using a lightbox that Jim designed, something to make the actors more appealing,” Soderbergh says. “I might not do that on every movie, but I did it on this because it’s that kind of movie, a movie-star movie. For instance, when Ocean and Tess meet in the restaurant, I was trying to adopt a very classical Hollywood approach to their close-ups to make them warm and appealing.”

The filmmakers applied some of those same techniques on the casino floor, but on a broader scale. “We wanted to be able to shoot with pretty much available light in the Bellagio,” says Plannette, “and then use some fill in the foreground or bounce off the ceiling for the background wherever we could.”

Soderbergh interjects, “The big job was replacing all of the 50-watt ceiling bulbs with our own 150-watt bulbs.”

“All of the lights in the casino were on a dimmer,” says Plannette, “so we had them brought up to 100 percent, whereas they normally work at about 40 percent. We built some light boxes in which we put Number 1 and Number 2 Photofloods on a Variac. We used those for front fill for tracking shots; we’d put them on a pole and walk along with people. We varied it a bit to give an indication that they were walking in and out of light. Sometimes we used those light boxes for edge light depending on how tight the shot was. On wider shots, we used traditional Tweenies or Babies, often not very soft. There was justification for that in all of these locations because of the bright lights in the background.”

There are a couple of shots where I feel like it’s not as natural as it should be, or that I went too far with trying to edge people out,” Soderbergh reveals. “Some of the shots I’m happiest with are moving shots where we either mounted a light with us that we were bouncing into the ceiling, or we just let it go [directly]. I should have gone that way more often.”

Most of the time in the casino, Soderbergh was shooting right at T2/2.8 split, and for one particular shot of Clooney at a slot machine [above], the filmmakers happened upon the lighting setup in true Las Vegas style: by chance. “The surface of the slots was so reflective that we placed a Par above him that we pounded into his slot machine,” Soderbergh says. “The light came back up in a way that turned out to be really perfect for us. We got lucky.”

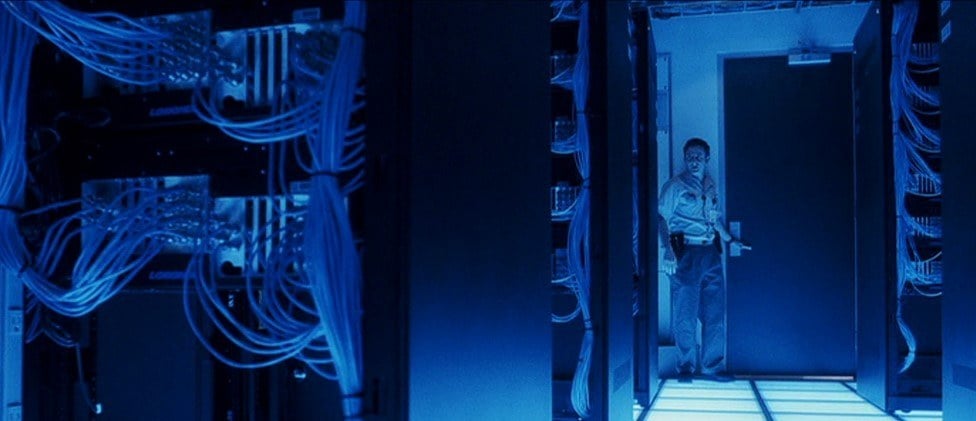

Meanwhile, electronics expert Livingston Dell weasels his way into the casino’s machine room to tap into security camera feeds, a room that seems as if it was constructed inside an electric-blue light fixture. “I wanted to go for that super-saturated monochromatic blue,” Soderbergh explains. “I was tearing pictures out of a magazine for a film that I’m supposed to do this spring, and in putting the pile together I’d accidentally inverted this machine-room picture. It looked so much more interesting upside-down that I talked to production designer Phil Messina and said, ‘Can you make the floor the ceiling so that all the lights are coming out of the floor?’ He replied, ‘I don’t see why not.’ They’re really heavy blue fluorescents that Jim had told me about.”

“They’re fluorescent tubes that I first used about 20 years ago on commercials with a really innovative cinematographer-director named Melvin Sokolsky,” says Plannette. “He was a still photographer in New York, and he used a lot of multi-colored fluorescents in his stills — reds, greens and electric blues. He carried them over to his commercials. Steven and I put those under the Plexiglas floor in the room to give it a really eerie blue feel.”

Soderbergh adds, “Then we had these little MR-16 can lights up top that we let go tungsten just to add a tiny bit of flavor whenever [Dell] was directly under them.”

In stark contrast to the warm, plush comforts of the casino is the cold, underground vault set, which is rendered in shades of white, black and brushed aluminum. Variances in the light create the scene’s contrast. The vault ceiling was tiled with opaque plastic squares that are typical of business fixtures, and above those were space lights. “The space light is a very versatile light because it has six fixtures in each light, and you can control them by the number of globes that are turned on,” says Plannette. “We were able to use those in different amounts depending on the sequence. Once the vault explosion takes place, we used fewer of them. The hallway was lit with fluorescents in the ceiling and Lowel sockets along the floor.”

After the gang pulls off the greatest heist in Las Vegas history by ripping off Terry Benedict, they return to their warehouse base of operations in a SWAT van. (Remember, these are con artists.) To show the van driving in — what might normally be a throwaway transitional scene — Soderbergh stylized the lighting with a moving shaft of sodium vapor-colored light that beams through as the garage door opens, and he also added subtle camera movement. “It’s a weird effect,” he says. “That was one of those days where I was trying to figure out how to shoot what in essence is a very simple scene. I remembered we had already shot Andy Garcia going into the elevator, with the doors closing and going to black. In theory, those elevator doors shouldn’t have been black. They were metallic doors, so they should have been reflective. For some reason — and I didn’t realize why until later — when we were shooting that shot of Andy, I said, ‘Tent me in because I want the doors to go in silhouette.’ Dramatically it just looked better. Later at the warehouse, I remembered that what preceded the scene was the black elevator doors, so I said, ‘Turn out all the lights. Let’s just put one light outside pointing in, but no fill light in the garage.’”

The opening of the automatic garage door allowed the shaft of light to shine more and more into the pitch-black warehouse to backlight the van. Soderbergh tilted the camera up from the blackness to frame the van as it rolled in. “If Warners were actually aware of how much was being determined moment to moment on this movie, they’d probably be horrified, but that’s the way I work,” he says with a chuckle. “By accident, we came up with these shots that look like they go together.”

Says Plannette, “We had a 20K on a Condor with a GAM #382 Brass in front of it. It’s as close to sodium as there is, I think, which is what I like about it. Sometimes we added a little bit of green to it, but in this case we didn’t. But it does cut quite a bit of intensity, so you need a pretty big unit to go through it. We were shooting at about a T2/2.8 split so that we held the background.”

“Dramatically,” Soderbergh reflects, “one of my favorite shots in the movie is a long tracking shot of Tess where she’s left Terry Benedict and realizes Danny is still around somewhere. You see all that play out on her face. It was 200 feet or more of track. What we ended up doing was mounting a light on the camera as an eye-light. We had that on a Variac. We hooked a second dolly to my dolly, and on the back of it we mounted an edge light that was also on a Variac. So both lights were moving with us, but they were dimthing up and down in a random way.” Though it’s shot during the day but plays as night in the film, the dimming variances make it appear as though Tess is walking in and out of pools of brighter light, maintaining the natural quality prevalent throughout the film.

“There are a lot of things about the film that I really like,” muses Plannette. “Toward the end, all of the guys are standing outside the Bellagio fountains, and it’s very touching when it ends on Carl Reiner as he’s thinking about how it doesn’t get any better than this.”

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.