Photogrammetry: Stills to CG Realms

This technique has evolved over the past 150 years or so, and can now generate highly accurate visual representations of real-world objects and surroundings.

When lion and cub walked to the top of Pride Rock and looked out over the savanna in the 2019 reimagining of The Lion King, their view was a digitally rendered environment that would not have existed without visual information gleaned from multitudes of still photographs. These photos, captured in East Africa, were integrated into the production’s CG pipeline in part by photogrammetry — a process that creates 3D models from collections of stills.

The photogrammetry technique has evolved over the past 150 years or so, and can now generate highly accurate visual representations of real-world objects and surroundings. The fine detail and interactive, configurable nature of materials derived with the aid of photogrammetry have made this imagery ideal for display on the LED walls of virtual-production stages, where filmmakers capture live action within interactive visual-effects environments — all in-camera. With this [June 2021] issue’s emphasis on still photography, we thought it apropos to examine the role that a still-based system serves within this new frontier of filmmaking — and the role of the cinematographer in guiding the presentation of these images-within-the-image.

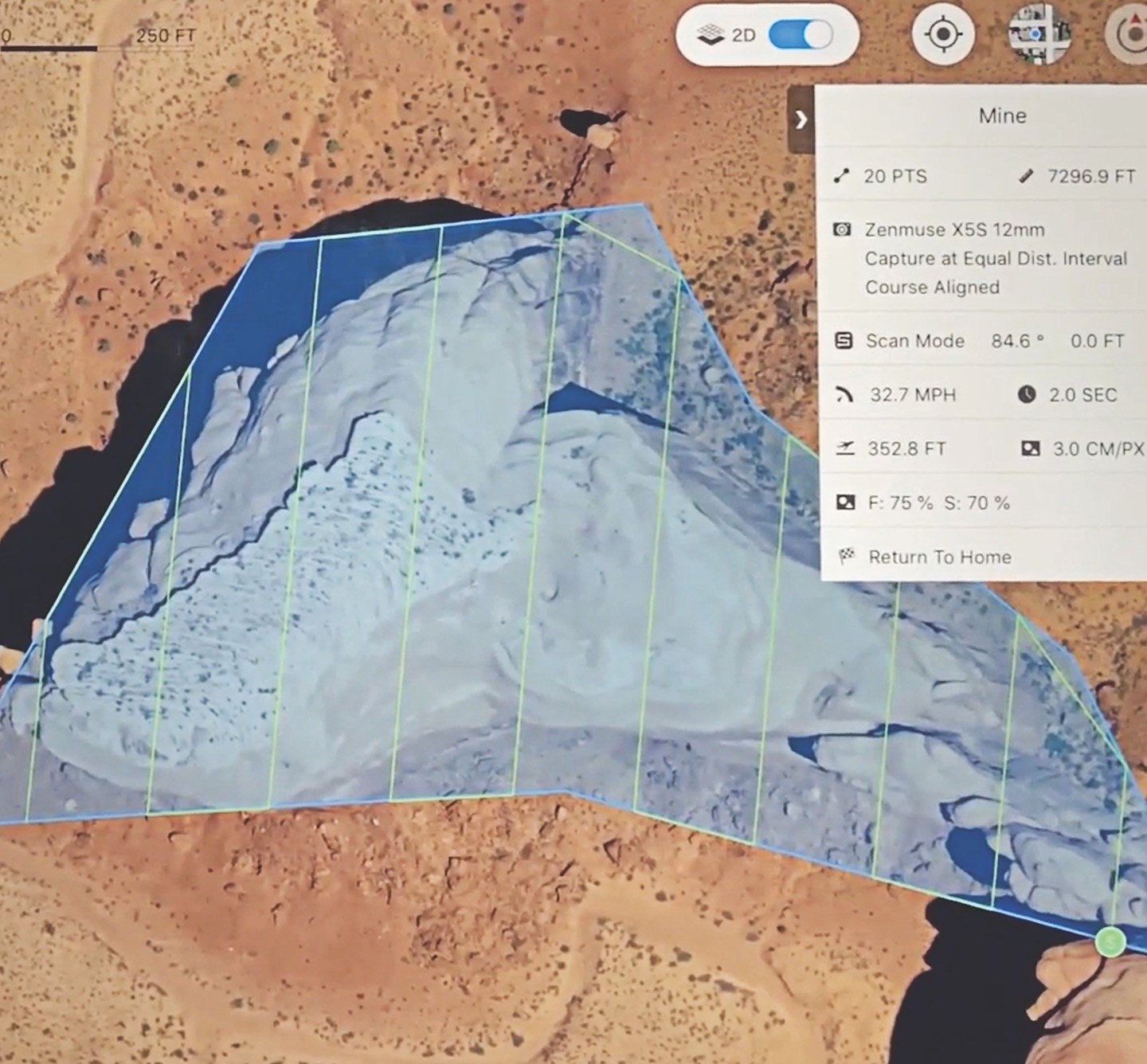

Photogrammetry relies on software-processed algorithms to generate measurements and geometry by comparing differences in multiple stills — either photographs or pulled from footage — that are taken of the same subject from different angles. Outputs can include a 3D texture, environment or even a 3D map, each of which can be an end product in itself or a means to create final imagery in combination with other CG techniques. Google Maps is a well-known example of converting satellite imagery and aerial photography into navigable 3D imagery via photogrammetry. In addition to the benefits photogrammetry offers to in-camera visual-effects capture, it is also used extensively in other virtual-production arenas, such as previs, action design, techvis, and postvis.

“It’s an efficient way to build out photorealistic 3D models,” says Chris Ferriter, CEO of Halon Entertainment, a Santa Monica-based visualization studio and technology company — which has employed photogrammetry in creating previs for projects like War for the Planet of the Apes and in-camera material for Season 1 of The Mandalorian (AC Feb. ’20). For the latter, he says, “We built environments, props and scanned minia-tures using photogrammetry. You look at something like 2001: A Space Odyssey [AC June ’68], and its effects hold up today because there’s a realism that comes along with shooting real miniatures. Photogrammetry gives you a similar creative advantage.”

Director of photography Baz Idoine has shot 10 episodes of The Mandalorian — work that has earned him both an ASC Award and an Emmy — and he views the cinematographer’s input as critical in helping to shape photogrammetry-derived assets as they’re prepped for the LED wall. “It’s extraordinarily important, because you’re basically creating the lighting environment,” Idoine says. “This is especially true if you’re shooting in a 360- or near 360-degree LED volume, as opposed to a less encompassing LED wall. If you’re not involved in the pro-cess, then you’re just coming into the volume and being a documentarian.”

Idoine collaborated with ILM’s photogrammetry team — led by environment supervisor Enrico Damm — which was responsible for (among a variety of other elements) creating skies to serve as the background of many of the show’s virtual sets, and as a principal source of lighting for exterior scenes shot in the volume. “The director, production designer and I would review the skies both for the technical and creative requirements of each load,” adds Idoine. “We would look at them as panoramic images on a computer screen, or very occasionally within the actual volume, to confirm we were making the right choices. I’d also be looking for specific lighting components, such as sunset skipping off the clouds, or random clouds I could use to motivate brighter and darker areas when moving from wide shots to close-ups. The goal was always to make the light feel natural, just as if you went out into a real desert with bounces, fills and negatives.”

To achieve more accurate 3D geometry, the process of collecting data for photogrammetry often includes Lidar scans in addition to the still images. Lidar data is represented as a “point cloud” of 3D coordinates taken from different vantage points. Several solutions exist to combine the imagery and point-cloud information into a completed 3D model. Capturing Reality’s RealityCapture is one such app; it was recently acquired by Epic Games, the makers of the Unreal game engine widely used in virtual production. RealityCapture uses machine-learning algorithms to process overlapping images and solve their geometry by analyzing parallax. It can re-create small props, create hu-man digital doubles, or capture entire physical environments for virtual productions.

Another photogrammetry resource is the Quixel Megascans asset library. Quixel is a digital “backlot” comprising thousands of 3D models, each of which began life as a series of still photographs captured and processed with proprietary techniques. Megascan assets include surfaces, vegetation, and small- to medium-sized objects, fully standardized and based on actual physical objects. Recent high-profile projects that have employed the Megascan library include The Lion King (AC Aug. ’19) and its predecessor The Jungle Book (AC May ’16), which were both captured with virtual-production techniques on motion-capture stages.

The photogrammetry process leverages the inherent detail of still photography to deliver photoreal visual-effects imagery efficiently and cost-effectively. When such material is destined for in-camera capture, the cinematographer steps in to help shape it — and, as always, give it context and intention.