Photography on Poltergeist II: The Other Side

Andrew Laszlo, ASC describes shooting the follow-up to one of the most famous ghost stories in cinematic history.

This article originally appeared in AC July 1986. Some images are additional or alternate.

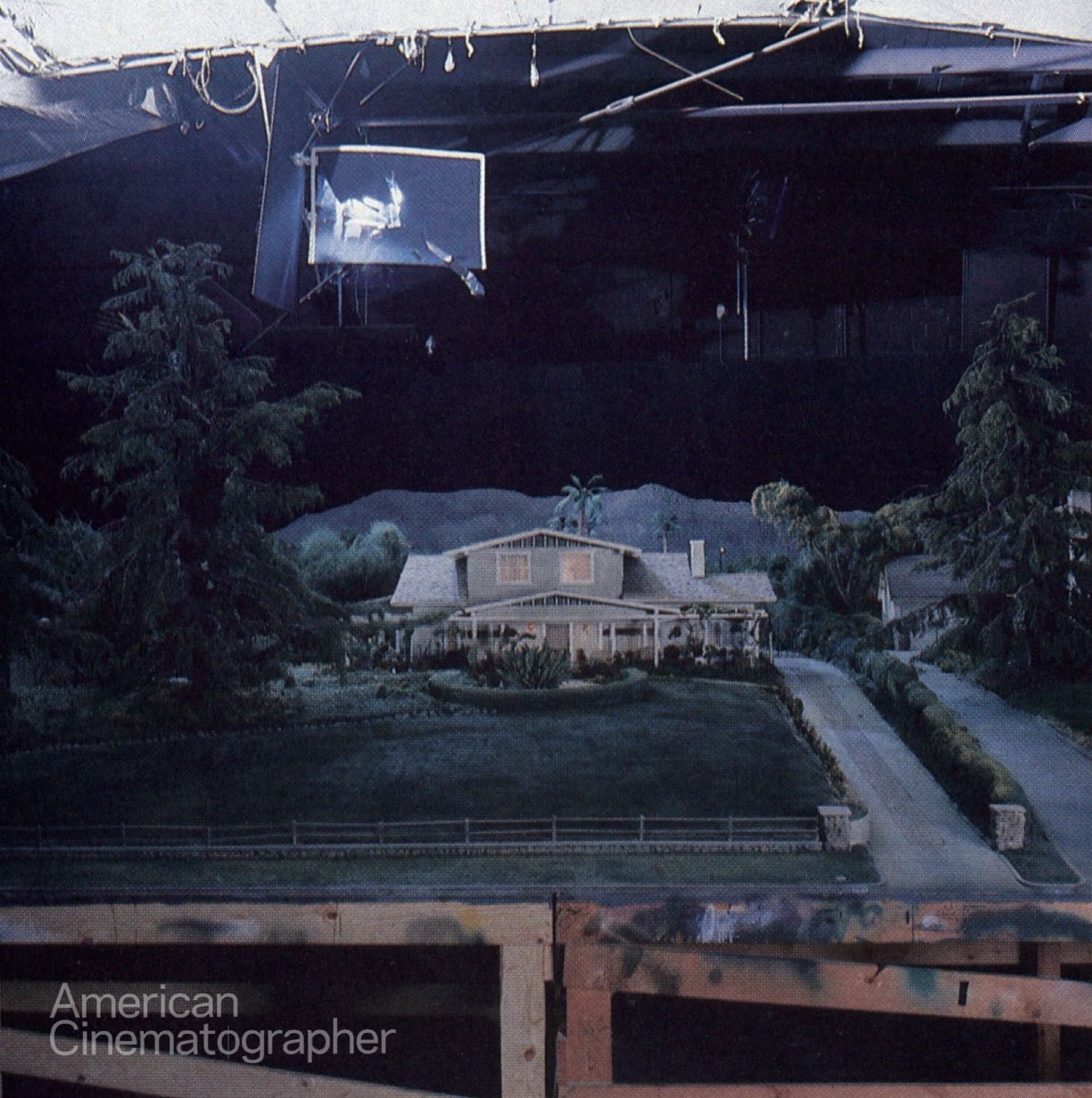

In Poltergeist II: The Other Side, America’s favorite target of psychic activity, the Freeling family, is once again hounded by ghoulies and ghosties and long-legged beasties. Flattening their Cuesta Verde tract home and scaring them all half to death wasn’t enough for those vengeful spirits, who have followed the Freelings to a new residence in Arizona, determined to continue the reign of unholy terror they began in 1982 with Poltergeist.

The man responsible for capturing the stark terror of the Freeling family on film is veteran cinematographer Andrew Laszlo, ASC, who adamantly maintains that despite its horrific content, Poltergeist II is not a horror film. “Poltergeist II is a very scary film,” he concedes. “It has some very scary elements, but we’ve tried very deliberately and taken great pains not to have those elements that standard horror films have: the elements that make people jump out of their seats without regard to the film’s content, story and continuity. Poltergeist II is the story of a family that is haunted through the generations from the grandmother to the mother to the little daughter, and nobody knows why or who by.”

“It is essentially a very scary movie and it uses all the elements available to make a movie scary through photography.”

— Andrew Laszlo, ASC

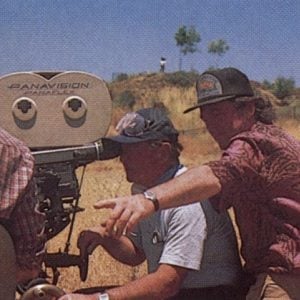

Though certain elements of Poltergeist II were deliberately designed to meet and satisfy the expectations of the audience whose appetite has been whetted by the first film, the current production has a far less brightly lit quality than Poltergeist, since Laszlo and director Brian Gibson opted to go for a more dramatic, more disturbing photographic tone. “However, a lot of the characteristics of the original film were followed simply because, I suppose, everybody felt it would be a good policy to stay in step with what had been a very successful motion picture,” Laszlo says. “The cast is basically the same and we follow the same family through their second ordeal, but that is where the similarities start and end. Brian Gibson obviously wanted to put his mark on the film, and I believe he has accomplished that. The flavor of the film is slightly different from Poltergeist because the story is different and because all of us have a different vision, a different imagination and a different method of execution. It is essentially a very scary movie and it uses all the elements available to make a movie scary through photography.”

While Laszlo’s career in motion pictures is lengthy and his depth of experience unfathomable, Poltergeist II marks director Brian Gibson’s second feature. Laszlo found working with Gibson to be a rewarding experience. “Brian has had a very lengthy career in England with documentary films, and commercials,” the cinematographer explains, “and that was an extremely good background for this film. I think what it really comes down to is talent and the desire to interpret that script and do the film, and Brian had no shortage of that. He is a talented director, and it was, in some ways, very fortunate that his second feature — his first feature in the United States — is really the big picture of the year for one of the biggest studios, MGM. It put tremendous pressure on him, but he has done a good job. The film is, in my opinion, very even, it holds together well, and I don’t think the suspense ever lets up. Even when the action is light, the tension is always there.”

One of the first indications of that tension in the film occurs at a shopping mall where the Freeling’s daughter, Carol Ann, suddenly feels as though she’s being followed. “Indeed,” Laszlo confirms, “there is this man in a strange looking outfit and hat walking through the shopping center, and when the little girl looks back and sees him, she is horrified and she doesn’t know why. From then on, the apprehension builds, and we took great pains to find aspects of the shopping mall, located in Encino, California, that were not too bright. The spirit of Kane, played by Julien Beck, comes out of a dark, enclosed corridor where the far end is open and very bright, so he is silhouetted by the bright background and you really cannot read his face until he walks out into the light. Then, of course, he walks through people and people walk through him, and the little girl realizes he’s a spirit — he’s not alive.”

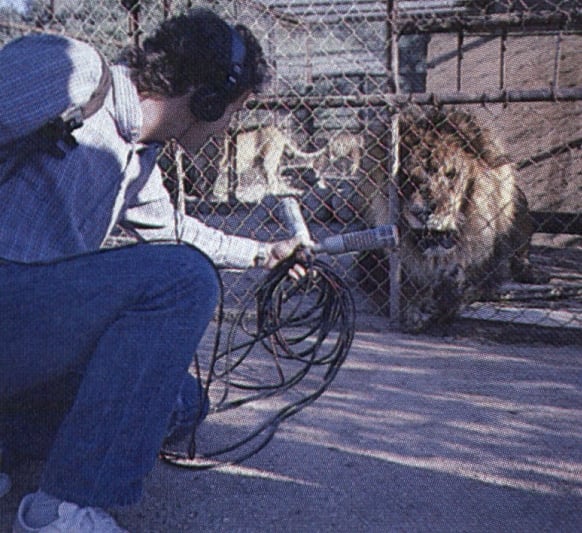

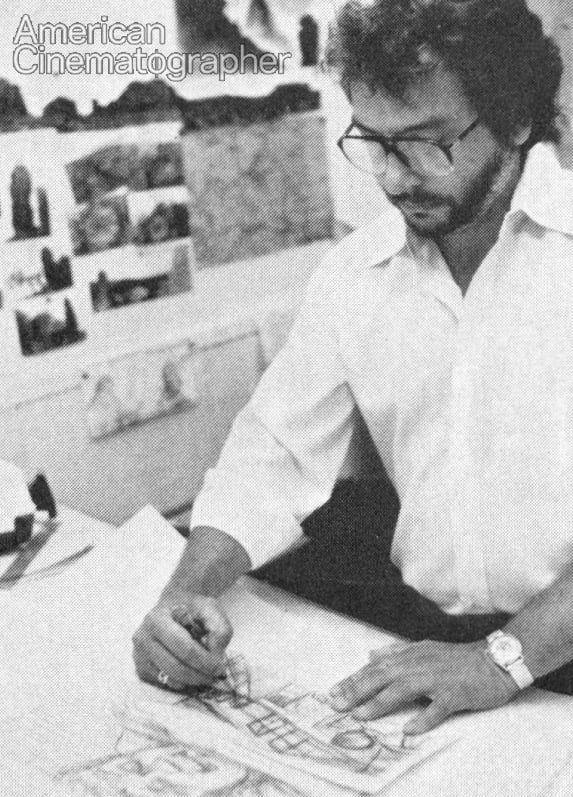

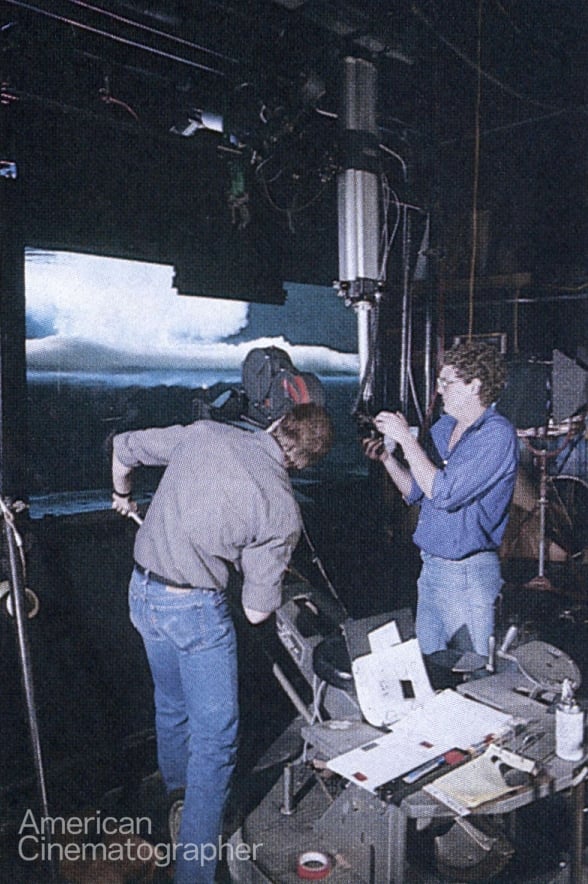

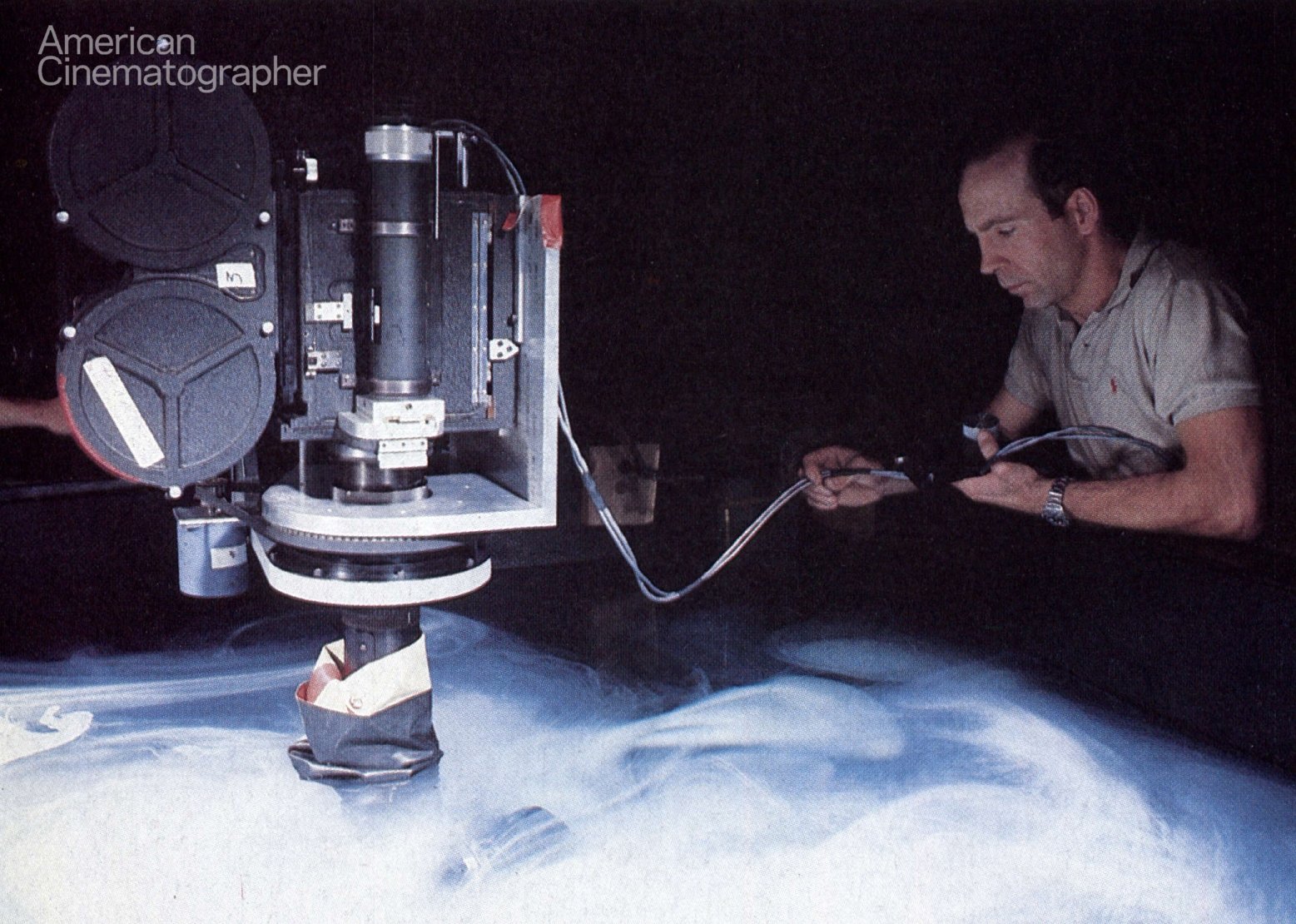

Due to the large number of special visuals required for Poltergeist II, there were several weeks of bluescreen and other effects photography shot on the stage at Boss Film Corporation by their in-house special effects cinematographer, Bill Neil, who has worked with Richard Edlund, ASC for the past six-and-a-half years. “Bill Neil is, in my opinion, one of the outstanding experts in that kind of photography,” Laszlo states. “He knows a lot of things I don’t know — how the particular photography of a person hanging on a thin wire will be included in a shot while all the other objects, such as equipment in that shot can be eliminated later. I was on that stage with Bill every day, and it was important for me to be there from the very beginning, not just because I wanted to see what he did, but because I wanted to consult with him about what to do in certain instances, knowing what I was going to do with the particular scene for which he was shooting the elements, and, of course, I had to be there to consult with Brian.”

Once principal photography began, Laszlo often found his crew working side by side with the Boss crew since any of the shots that were to incorporate matte elements, blue screen elements, or other effects footage had to be photographed in 65mm, as opposed to the 35mm anamorphic format of the rest of the film. This created some difficulties in terms of the lighting, which, for instance, required a much higher T-stop than Laszlo preferred to work with. “There was no difference as far as the style of the lighting was concerned,” Laszlo points out, “but there was a significant difference because of the requirements of the 65mm equipment and because of the special effects photography. Special effects photography uses 65mm equipment to begin with because they get a much more detailed and sharp negative, obviously. The negative image is quadrupled from 35mm, so that everything is four times as sharp and four times as well defined. Because of the equipment, because of the requirement of a great depth of field and the special requirements of that type of photography, I had to be working at a much higher light level than I would normally work at on a dramatic motion picture which requires low key photography for effect. So when they told me they would like to have enough light for a T4 or 5.6 stop, that was so high above the light level I like to work with, that it almost took some reorientation to do it. You have to know when to say, for an artistic reason, “I really don’t want to light this shot for a T-stop of 4 or more, but I know if you shoot it at my light level, stopped down to T4, we can safely rely on the lab to give us that little push in printing we’ll need to get a good, gutsy image on 65mm negatives. Of course these and other limitations complicate one’s life. The cinematographer’s art, unlike painting or sculpting, is more restricted by the equipment and the techniques and the materials available, and the total of all of these factors comes up as the final image. So along the the way, we cinematographers like to eliminate difficulties rather than having to deal with them. Somewhere amongst all the technicalities and mechanics, you have to find that small, or sometimes very large, area we refer to as visual art.”

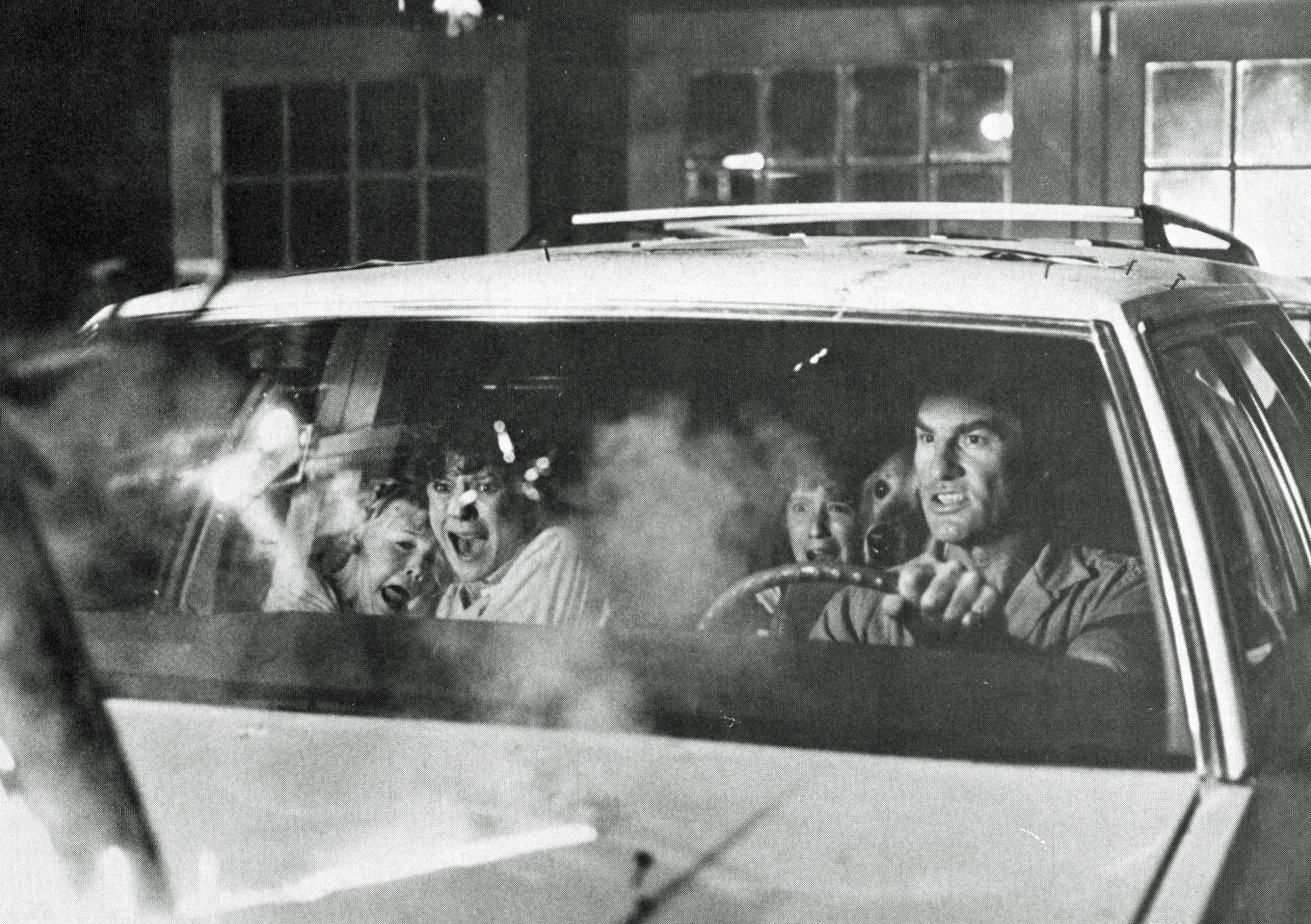

Laszlo did not allow the difficulties of lighting for 65mm interfere with his highly individualistic methods during the making of the film. There are two specific sequences in Poltergeist II where Laszlo used unorthodox techniques to produce strikingly eerie lighting effects. One instance occurs at a time when the family makes a desperate bid for freedom, trying to escape from the house using the station wagon in the garage. “When they run into the garage,” Laszlo recalls, “the spirits continue to attack and an electrical conduit tears itself loose from the electrical boxes and sockets, and sparks as it swoops around like a snake. At that time, the lighting was accomplished in a manner I’ve used successfully before in other pictures. Interestingly, on the largest stage at MGM, with a wealth of electrical and lighting equipment available, we brought in two arc welders and we kept striking steel plates with brute carbon replacing the welding rods so that not only did we see the sparks coming out of the electrical conduit, but we had huge flashes occurring in various spots in the garage.

“Sometimes the actors were silhouetted against a wall that had a huge flash on it, and sometimes they were front lit by a flash that was directly in front of them. We used the arc welder as a supplementary device that would produce not only a shower of sparks, but also a blue flash at those times when we needed it. There are, of course, several conventional ways of creating flashes, but none of them could give me the quality flash that we achieved with those arc welders simply because they were unpredictable. We didn’t know how big or small or frequent the flashes were going to be, there was no consistency, so the result was always interesting. There were other sources of light as well. The actual lighting is provided by the ceiling lights in the garage. There were two of those, one of which got blown up when the electrical conduit pulled loose.”

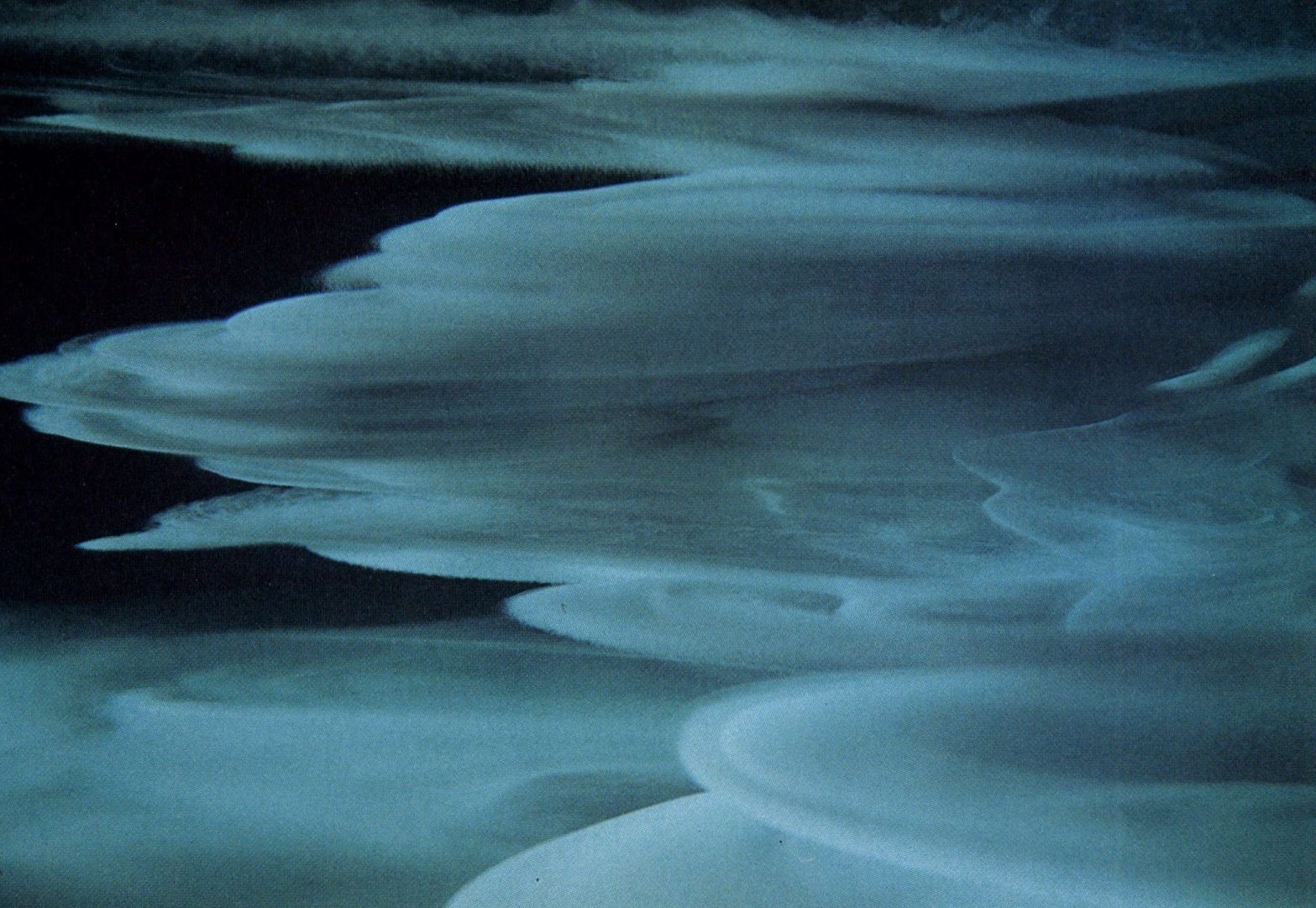

A sequence depicting Steve and Diane Freeling’s descent into an ancient subterranean cave — where over 130 years ago, the members of the religious cult led by Kane all perished at the same time — provided Laszlo with yet another opportunity to use his innovative and unusual lighting to great advantage. “The cave was a challenge,” Laszlo remembers. “It was very difficult to work on that set. We had to create a horrible feeling, and come up with an interesting image which, technically was very hard to do, because of the way the set was designed and constructed. The results, in my opinion, are very satisfying."

“I don’t think there’s a single picture I’ve worked on where I haven’t suddenly come to a scene and looked through the camera and realized that I’ve caught one - you know, the big fish had hit the line — and I think that the sequence in the cave might be just that, and I feel that it was the high point, as far as my photography is concerned, of this film.”

"The difficulties involved were that I was working on a set for a cave that was really a cave, with a full ceiling. We saw 360 degrees, so it was very hard to light. We had several shots that were lit by candles, and we had several shots that were lit by Coleman lanterns, a device I used in [the Rambo film] First Blood. Of course, the quality of the light coming out of a Coleman lantern is somewhat different as far as color temperature, as far as direction, as far as intensity, as far as consistency — it’s different from one designed for motion picture lighting. It does one very interesting thing, however, the lanterns move with the actors carrying them and when they move, the lit areas and the shadows move, continuously changing the atmosphere. The area where the actors are is lit up as they progress through the set, so you don’t see things immediately, you see them as they see them. The actors were carrying the lanterns, and in fact, Craig Nelson who plays Steve, the father, had collaborated with me in that I carefully laid out for him what to do with his lantern at certain times during the particular scene we were photographing. He did such a beautiful job that I offered to help him get a card in the electrician’s local! Seriously, I’m very grateful to him. He was not only able to do a great job acting under some very difficult conditions, but he effectively helped me light the scene. It was hard to work in the cave set. Once we got on the set, we were in a stone tunnel with grades and dripping water where cast and crew slipped all over the place There were some fast camera moves, handheld, Panaglide or dolly shots. We went through the water and often had to film through tiny little openings in the walls of the set. The difficulty was great, but then again, nearly every film has its difficulties and that’s what makes my end of the business so tremendously enjoyable. There never was a standard script that I could pick up and say, ‘This shot is a standard #47.’ At times, all the preparation that a cinematographer makes — and there are weeks and weeks of it - we get on the set and have to improvise on the spot at the very last second!”

Although Laszlo like to experiment with highly unorthodox lighting techniques, he is a firm believer in motivated light within a given scene, provided he feels that “it serves the script and the moment of the story as best as I think it should be served.” In other words, certain scenes require a more stylized lighting treatment in order to come across effectively. One such sequence involved a series of shots of Steve Freeling as he is gradually possessed by the spirit of the great beast after swallowing a sinister tequila worm. “When Steve first starts out drinking, he is in a very normal lighting situation, sitting in his den in his comfortable leather armchair. As he continues drinking and gets drunker and drunker, he goes up to the landing halfway between the level of the den and the bathroom. He sits down on the landing and drains the bottle to the last drop. The worm goes into his mouth and we can clearly see that he swallows it. By this time, the lighting is becoming much more pronounced, more shadowy, more mysterious, and yet still within the realm of an acceptable situation, but we’re beginning to take artistic license. After he swallows the worm, he stands up and his face disappears into the shadow. When he turns to the camera again, within the same shot, the light has totally gone kaplooie! It’s just horrible — his face is changing, his eyes are bulging out, the light is coming from below him, and there’s nothing but darkness and shadows on his face. I threw a shadow across his face so only one eye can be seen as he moves in and out of that shadow. The rest of the light falls off as this transformation takes place. As he begins walking up the stairs, his shadow is projected on the wall, and though that’s the way it might look, it does have a very ominous feeling. Then he goes into the bathroom, which is perfectly normally lit, but by this time he looks weird and we know something is wrong because his daughter pulls away from him and he chases his wife into the bedroom and attacks her. The bedroom was lit by one practical light on a night table and another in the closet, supplemented by small units. As he attacks his wife, the night table is knocked over and the light falls on the floor and that becomes the major light source so that once again, there are shadows and the scene is back lit or side lit depending on where the camera is. When Steve finally disgorges the worm, we play that action against the light on the floor. The action is horrible, and it’s going to scare a lot of people!

It’s something extraordinary. The worm, now a rapidly growing beast, falls on the floor and crawls under the bed. The bed starts shaking and gets turned over. The creature crawls out and now it has a head and little legs and little arms, and the lighting, once again, becomes part of the mood, very sketchy and under-lit.

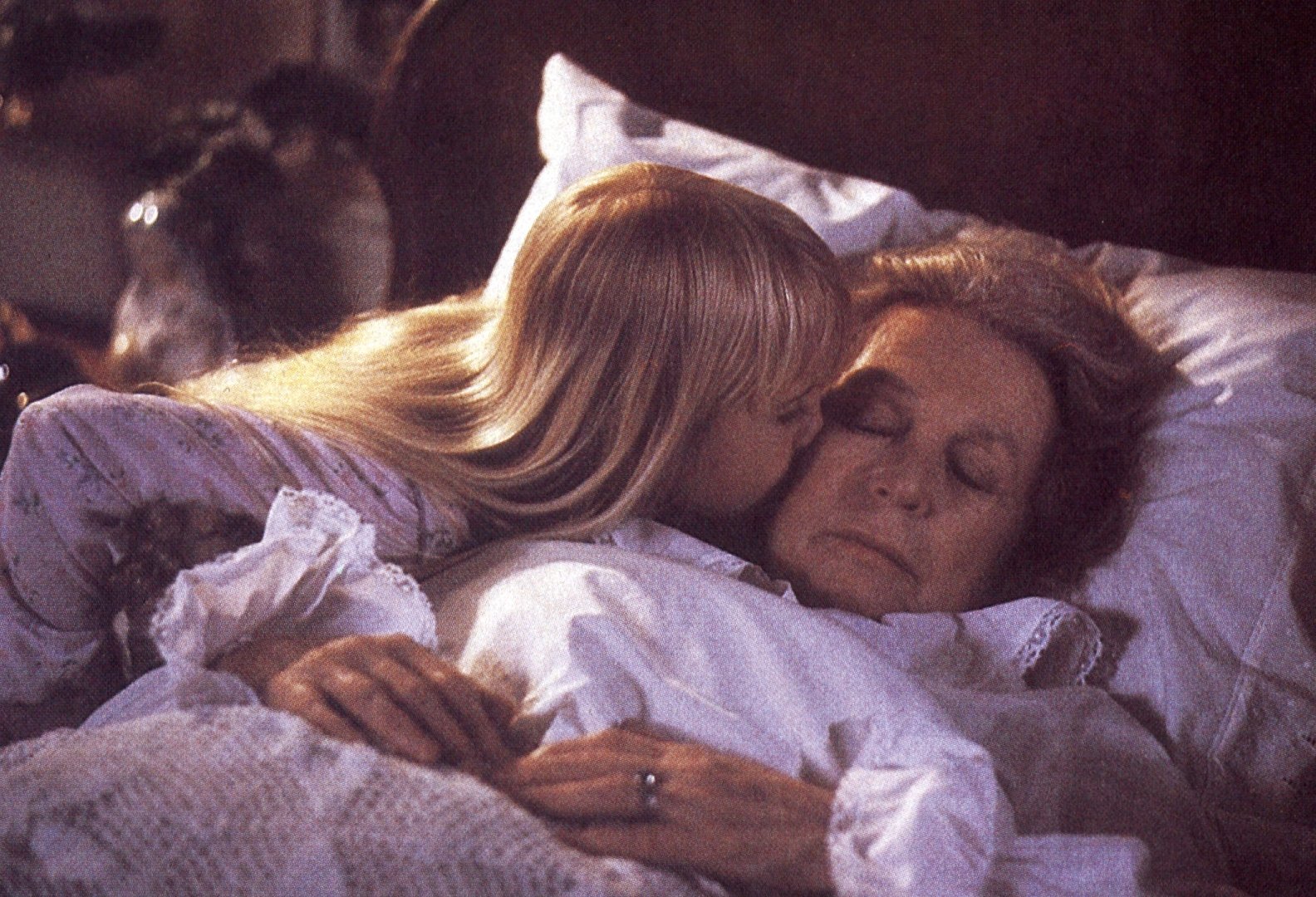

A rather extensive camera move that follows Carol Ann through the various rooms upstairs at night also required a highly stylized lighting approach. “As the shot begins,” Laszlo says, “you see the little girl sleeping between her mother and father in their bedroom. It’s what I would call a fairly standard, darkly lit night scene. Then she sits up and quietly gets off the bed and begins walking down the hallway, against a far wall that is lit so she’s a silhouette. I took the liberty of lighting up the wall, and if you question it, fine, I’ll tell you that it’s a night light downstairs. I doubt that anyone will question it. The little girl then goes into her grandmother’s room, which, by contrast, is very pretty. Even though she’s just died in there, it’s lit up in a higher key than the rest of the house. Why? Because it felt right for the scene and that’s the way we did it. That’s what the mood of that particular shot called for. She kisses the dead grandmother, comes out of that room and goes into her own room, which- is lit very low key, yet we can see everything because of little areas of light here and there. What lights it — who knows? Then she gets into bed, picks up the toy telephone on the floor and talks to her dead grandmother, and that’s the end of the scene. Even though I strongly believe in motivated light, in the case I just described, the idea was that the room was in total darkness, but if I put it into total darkness, you won’t see what’s happening. Not only that, but I think that as cinematographers, we have a wonderful opportunity to create feelings or to take an artistic license and create an illusion of darkness so that, yes, you’ll agree that this little girl walked into a dark room without any lights on and yet you could see everything.”

Because of his penchant for doing the unexpected when it comes to lighting and camera techniques, Laszlo prefers to work with crew people who have worked with him before and who understand his more unorthodox methods. For Poltergeist II, Laszlo was pleased to be able to bring on Dick Meinardus as his first assistant, Larry Hezzelwood as his second assistant, Don Nygren as his gaffer, Len Lookabaugh as his key grip, and Bob Marta as his camera operator — most of them have worked with Laszlo before and he regards them as “family.” He explains: “Most of the people on my crew have worked with me on a number of pictures, and it’s a wonderful feeling to know that you don’t have to give detailed instructions about what is involved with every shot. It’s a wonderful feeling to know that you have the friendship, loyalty, expertise and support of these people.”