An Eye for the Cameras: Richard Edlund, ASC

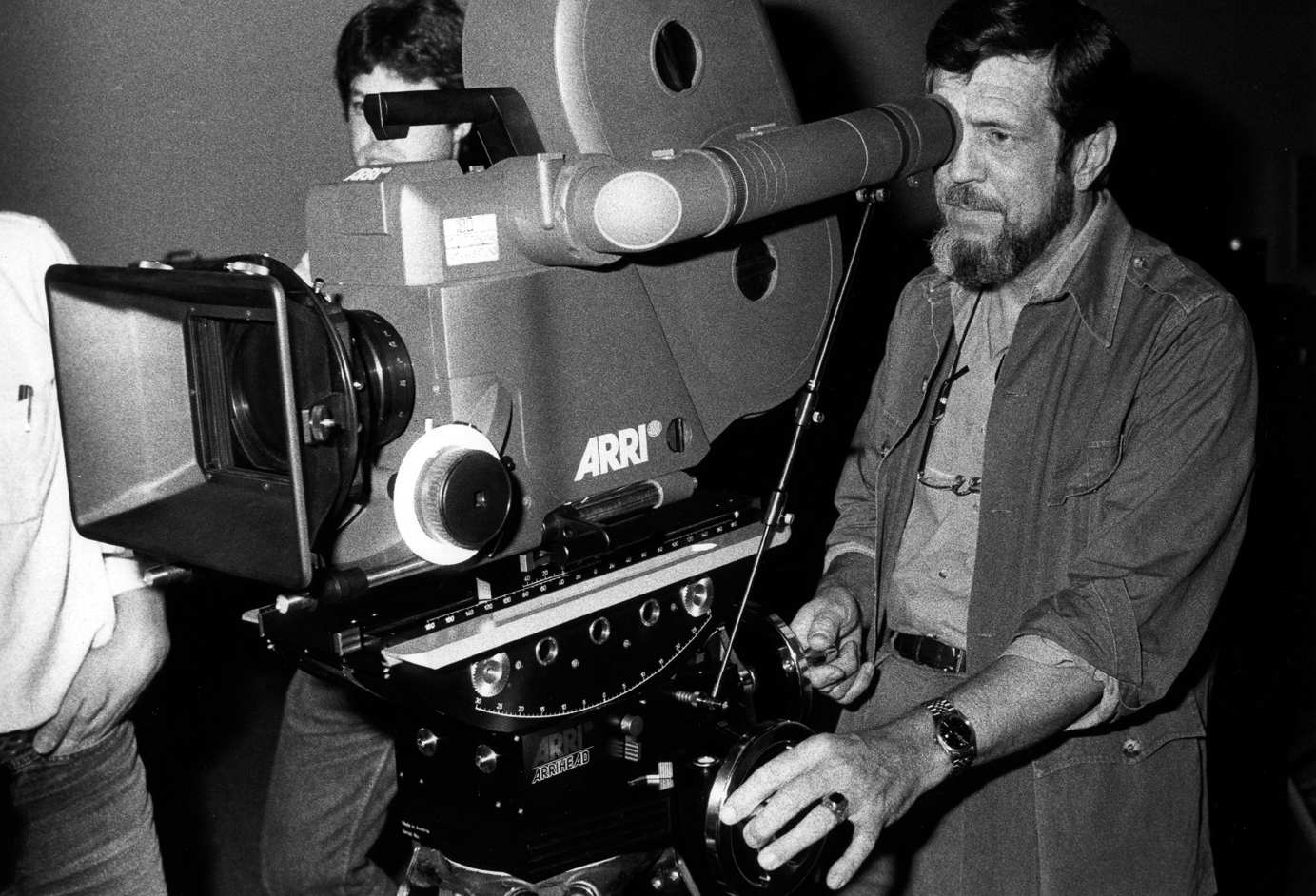

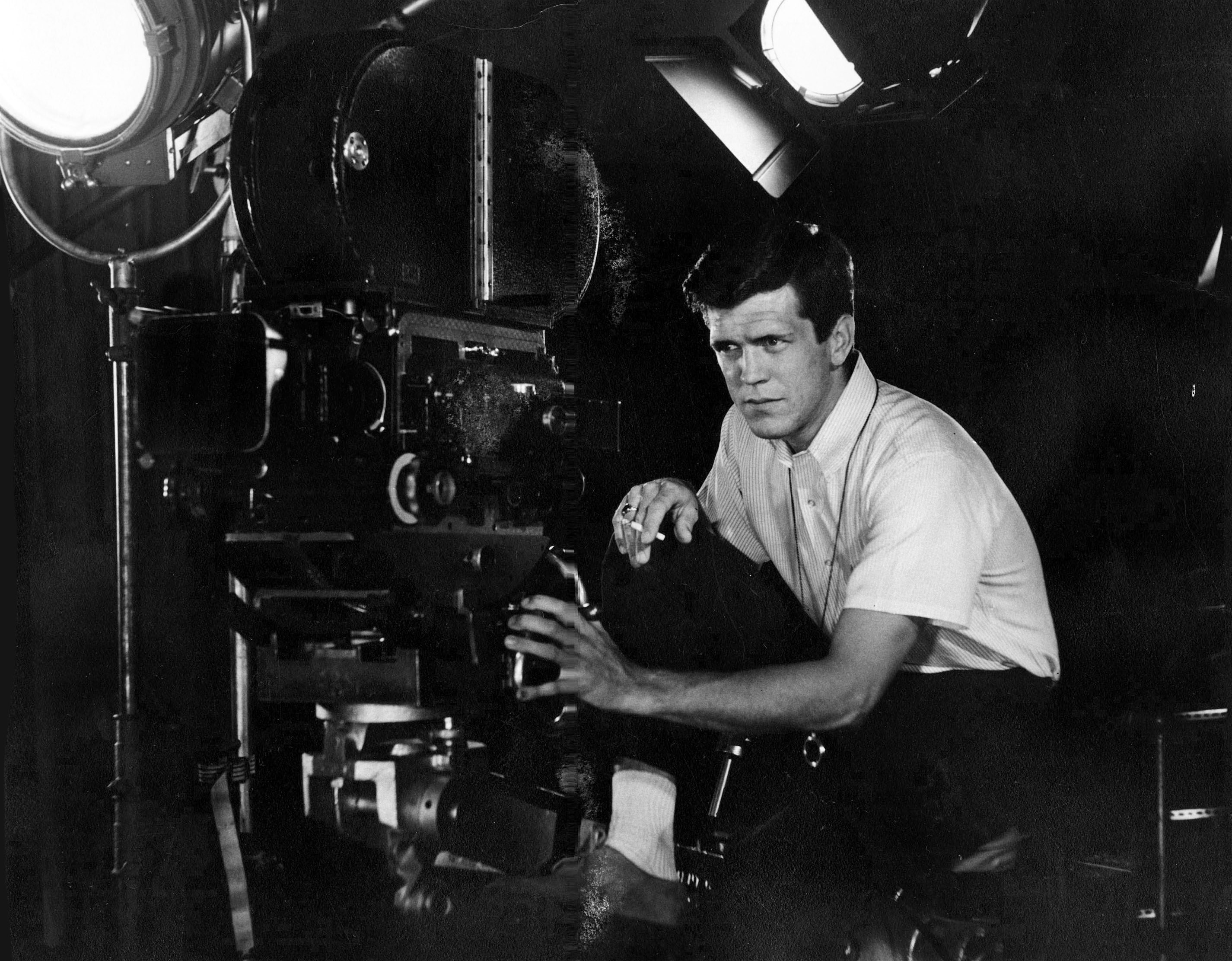

The visual-effects icon looks back at his illustrious career, and shares his passion for cameras with a pictorial of select models from his world-renowned personal collection.

Camera photos courtesy of Richard Edlund, ASC. Other images courtesy of the ASC Archive.

The private workplace of Richard Edlund, ASC is an Aladdin’s cave of cinema history. Housed behind a modest storefront in midtown Los Angeles, artifacts include a three-strip Technicolor camera with provenance dating back to the Golden Age of Hollywood, a behemoth 65mm Mitchell BFC, and the 65mm tri-pack matte camera custom built by George Randle and used by visual-effects legend Douglas Trumbull to composite images for Close Encounters of the Third Kind and Blade Runner. A cabinet of still cameras contains Leicas, Nikons, Rolleiflexes, subminiature Minox spy cameras, and other favorites. Edlund’s adjoining office is home to a library and display of career accolades, including four Academy Awards for Best Visual Effects (for Star Wars: Episode IV — A New Hope, Star Wars: Episode V — The Empire Strikes Back, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and Star Wars: Episode VI — Return of the Jedi) as well as three Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Scientific and Engineering Awards, honoring his work on the “Empireflex” motion-picture camera system, the beam-splitter optical composite motion-picture printer, and the 65mm zoom aerial printer.

“If you look at a movie as an amateur, that means that you don’t have a preconceived notion of how to solve all of the issues. You remain an amateur committed to getting the job done. You have to invent or collaborate yourself out of amateurism.”

The trophies are evidence of a rich cinematic history and a lifetime’s advocacy for the craft. Edlund was the founding chair of the AMPAS visual-effects branch, a sector he helped define, and its governor for 23 years. He was the 2007 recipient of the AMPAS John A. Bonner Medal of Commendation, the 2008 recipient of the American Society of Cinematographers’ Presidents Award, and the winner of the 2013 Visual Effects Society Lifetime Achievement Award. Edlund is also famous for inventing the Pignose guitar amplifier and even performed as the disembodied hand Thing in the title sequence for the 1960s television series The Addams Family. That same hand created the still-in-use, oblique title font for Star Trek. In short, his is a storied career.

Catching the Camera Bug

Edlund attributes his interests in technology to his early years in 1940s Fargo, N.D., where his father worked for a custom truck-body company. “I had a hammer and saw in my hand as a very young kid,” Edlund recalls. “I struggled with math, but my father made me learn multiplication tables by the time I was 5. I started school at 5, which made me the youngest kid in class through high school.”

After a family move to Minneapolis, Minn., Edlund’s interests expanded to print shop, electric shop, wood shop, metal shop, “Boy Bachelors” home economics, and mechanical drawing. “One of my uncles was an architect. I used to watch him draw, and I developed an architectural style of printing.” A session with Fargo portrait photographer Walter Schramm piqued Edlund’s interest in cameras. When a Montebello High School friend loaned him a pocket-sized Minox — with a 15mm f/3.5 lens, and 50-exposure 8x11mm film cartridges — it unleashed a photo bug in Edlund. “I took surreptitious photographs in school, a lot of them came out and I thought, ‘Gee, this is great!’ That’s what set the hook in me, photographically.”

After a move to Montebello, Calif., where his father started work for Aluminum Body Corporation, Edlund’s high-school teacher Wesley Walker introduced him to photographic optics and photochemical processes. Edlund converted a storage unit in his parents’ carport into a nocturnal darkroom and started to experiment using an old camera purchased from a friend. “It was 4x5, with a German Goerz lens, and a 1/200-second shutter speed. My buddy Dale threw in an enlarger, trays, the whole shebang.”

Edlund’s high-school interest in photojournalism led him to join the USN Airman Recruit Program, where he had the photographer’s E-5 rank. After boot camp, Edlund was transferred to Naval Flight Training Center in Norman, Okla., where he attended Operational Clerical Group prep school. He then transferred to Navy Photo School in Pensacola, Fla., to study photography, shooting with many different cameras and cine equipment. Edlund was then assigned to the Fleet Air Photo Lab at Naval Air Facility Atsugi in Kanagawa, Japan, where treasures lay in wait. “There were about 45 of us in the lab, and we had every kind of photographic equipment known to man. We had what we called the Crash Box, with ready cameras for shooting aircraft accidents, and also this big finishing room in the middle ringed with darkrooms. There was a photographic repair group, a processing lab with a big photostat machine, and a process camera with arc lights where you could shoot graphic photography with high-contrast film.”

Edlund shot his first motion-picture footage using a 16mm Kodak Cine Special to capture forced-landing mishaps on the neighboring airfield. The Atsugi base library had only one book on cinematic literature, A Grammar of the Film by Raymond Spottiswoode, father of filmmaker Roger Spottiswoode, which became Edlund’s introduction to film theory. “It was a treatise on the silent film. It discussed how the Russians used found footage to make propaganda films, by juxtaposing images to tell stories. That was my bible.” The discovery of a mint-condition 16mm Mitchell camera system, and a derelict Houston Fearless 16mm film processing machine, which Edlund restored, led to the formation of Atsugi’s motion-picture-training film department

Cinema Studies

By 1962, Edlund was enrolled as a full-time student in the USC Department of Cinema, on a tuition of $2,500 per year. He favored lectures on cinema classics by Professor Arthur Knight, film critic and author of the 1957 book The Liveliest Art, and on film writing by Professor Margaret Mehring, founder of the USC Filmic Writing Program.

After achieving three years of credits in two years, Edlund balked at the cost of a thesis film. “I couldn’t afford to do my senior year, so I put my resume into the Department of Employment in Hollywood. I knocked on a lot of doors, but because I wasn’t in the union, I got told to take a hike. It was a Catch-22. When I went to the union, they told me I had to have 30 days of work experience. And I didn’t have any relatives in the business.”

Joseph Westheimer, ASC, founder of the Westheimer Company visual-effects facility in Hollywood, gave young Edlund his first break. There, he created rostrum graphics and optical effects, initially for television shows, including Star Trek, The Outer Limits and The Twilight Zone. “I became Joe’s Boy Friday. I did everything. I did shots for Star Trek wherever they needed some special effect in the series. For the ‘beam up,’ I’d rotoscope one frame, shooting elements of mylar bits flying around, and light reflected off mercury on a white background to get strange patterns. They got composited. It was a pretty simple effect, but it worked.”

Edlund’s rotoscope effects assisted bluescreen shots of Star Trek’s 11' miniature Enterprise that Linwood Dunn, ASC photographed at his studio Film Effects of Hollywood on nearby Highland Avenue. “It was a pretty good-sized model. When it went off the bluescreen, we had to make a matte to hold it out in front of the stars. I did a frame-by-frame rotoscope to get rid of the pylons supporting the model and roto’d the ship for the frames that were left.”

During his four years with Westheimer, Edlund grew his hair and embraced the counterculture of L.A., but became a working hippie. His proficiency with one Nikkormat SLR camera led Edlund to shoot many rock bands, album covers, and 16mm “romp films” — progenitors of the music video — which included a wild, wide-angle handheld shoot for the Ventures’ hit record “Hawaii Five-O.” “I had a budget of $500. We shot out on a dry lake. It was just under two minutes, with 30 cuts or more — really fast cutting. It was pretty neat. I also did films for Wayne Cochran, Bobby Vee and the Animals.”

In 1974, Edlund’s work at Robert Abel and Associates, collaborating with visual-effects artists Richard Winn Taylor and Con Pederson, made a splash with the Clio-Award-winning 7-Up “Bubbles” commercial. “Richard Taylor and I developed a new animated graphic look that Bob Abel called ‘Candy Apple Neon.’ It was animated graphics on film footage of a dancer. I used diffusion filters, star filters, made-up filters, prisms, diffraction gratings, and all kinds of things to cause the animation to be lively and interesting. We used a motion-control system that Bill Holland and Ray Feeney came up with. It was digital, using quartz clocks for repeatability and punch tape to program camera moves using a surplus Western Union typewriter. Con made up the programs, and then we would create the artwork and I’d shoot it. Camera One’s track was about 30 feet long. And then, with the help of ace machinist Dick Alexander, I built Camera Two on a 14-foot track. I also built a lightbox, called the ‘Pizza Oven.’ That was a huge aluminum box with quartz lights inside that gave a perfectly flat 12-field for all the 12-field animation [a standard size for animation work]. It was like a horizontal rostrum camera.”

The innovative visual style of the "Bubbles" spot was carried over into the brand's continuing campaign:

Exploring a New Galaxy

In 1975, Edlund, Alexander, and a host of other bright young artists subsequently joined another future ASC member, visual-effects supervisor John Dykstra, for George Lucas’ Star Wars (now known as Star Wars: Episode IV — A New Hope), using computerized motion-control technology combined with an innovative approach to old-school effects techniques, including the resurrection of the 8-perf VistaVision format.

After a brief stint working with Dykstra on the sci-fi series Battlestar Galactica, Edlund rejoined ILM in its new home in Marin County and refined the studio’s photographic process to ensure the fidelity of composites for the 1980 New Hope sequel The Empire Strikes Back. “We always had a problem with optical printers that were aerial image printers. To make an aerial-image printer work, you have to have a field lens in between two lenses — the taking lens for the first projector, the second lens, a second projector, and a lamp house. Between the first and second projector, the required field lens bent light rays to illuminate the field. The problem with that was that a single plano-convex lens threw a monkey wrench into the optical path, causing chromatic and geometric distortions, and thus led to ill-fitting matte lines. In Empire, there could not be any matte lines on the light-gray Snowspeeders flying against blue sky, clouds, and snow.”

Edlund hit on a solution in Rudolf Kingslake’s 1972 book series, Applied Optics, and Optical Engineering. “Kingslake was the lens guru of Kodak, and he published those six volumes on applied optics. I was thumbing through those one night, and I came across a tank periscope that had a telecentric lens. It struck me that that could be the key to building an optical system without using a field lens. In a telecentric lens, light rays enter the lens almost parallel. But in this tank periscope, the telecentric lens had a very wide aperture, so you could see images very clearly. I pitched this to our optical designer, David Grafton: Could we design a telecentric relay lens between two projectors and a taking lens to accept a telecentric light path? That was the key to making our quad-printer. There was virtually no geometric distortion. We could rack it in and out of focus without changing the image size, or we could change the image size very slightly. It gave us the micro-ability to manipulate the image and eliminate matte lines. It was the finest optical printer ever built.”

Meet the New Boss

Following Edlund’s work on Return of the Jedi, a meeting with his peer Douglas Trumbull led him to return to Los Angeles, after the former revealed he was planning to close his Marina Del Rey studio, Entertainment Effects Group, which had contributed visual effects to such projects as Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Star Trek: The Motion Picture and Blade Runner. “I made the decision, right there,” Edlund says. “It was a fantastic opportunity. I wanted to get back to the center of movie production, so I made a contract with Doug and took it over. But it was like a parts drawer. Doug’s approach to visual effects was completely different than mine. He was not into compositing, and bluescreen was not his thing. He did a lot of great stuff without it, using front projection, but I was not a fan of front projection. Grafton had built Doug a 65mm version of the taking lens that I had built for the quad printer, but Doug was not using it as a composite printer — he was using it as a print-down. It was a bench printer, a projector, and a camera going from 65mm to 35mm anamorphic. I used that lens, but I had George Randle build another projector around it — and, phew, what a scene that was.”

Soon enough, a crack troupe of prior collaborators joined Edlund’s newly named Boss Film Studios. The studio flourished for 15 years, producing visual effects for 30 films including Ghostbusters, Die Hard, True Lies, Waterworld, Air Force One and Starship Troopers. The projects spanned a boom time in visual effects and marked a successful transition from photochemical to digital technology. It was an often-pricey evolution. “The digital equipment that was coming out at the time was extremely expensive. Then, $800,000 to IBM for the Power Visualization System, not including my software-development department! Not only that, but very soon that system became obsolete. I remember paying $30,000 apiece for a nine-gigabyte stack. I needed 25 of them!”

One of Boss Film’s most harmonious productions was director Harold Ramis’ 1996 comedy Multiplicity (AC July ’96), in which actor Michael Keaton interacted with three clones, featuring digital composites to enhance the cinematography by László Kovács, ASC and production design by Jackson DeGovia.

“We were the three amigos,” says Edlund. “That was one of my very favorite movies that I worked on. The shots came out perfect. Michael Keaton was so on top of it, and we were working with great stand-ins using motion-controlled laser-positioned video so that Michael’s eye line was dead-nuts, and his timing was perfect. We had a 40-foot trailer on set full of guys furiously jury-rigging equipment and making quick-and-dirty comps for Harold to see in video village, but the production crew wasn’t aware of or bothered by it. My promise to Harold was to make the effect possible without it feeling like we were going to the moon, or tripping up the actors. The thing with comedy is you don’t do 12 takes. For most of Multiplicity, we went mostly to three or, rarely, four takes. A lot of times we got it on one and just did another so we had a backup. And I knew that Harold Ramis was not going to screw us by making us do a shot that was going to cost too much simply because he wanted it. That was always one of the difficulties in that business. Sometimes, if a director can keep revising, they will, without pity.”

Edlund ascribes his abiding passion for the craft to the same curiosity that first sparked his interest. “If you look at a movie as an amateur, that means that you don’t have a preconceived notion of how to solve all of the issues. You remain an amateur committed to getting the job done. You have to invent or collaborate yourself out of amateurism.”

An Iconic Opening Shot

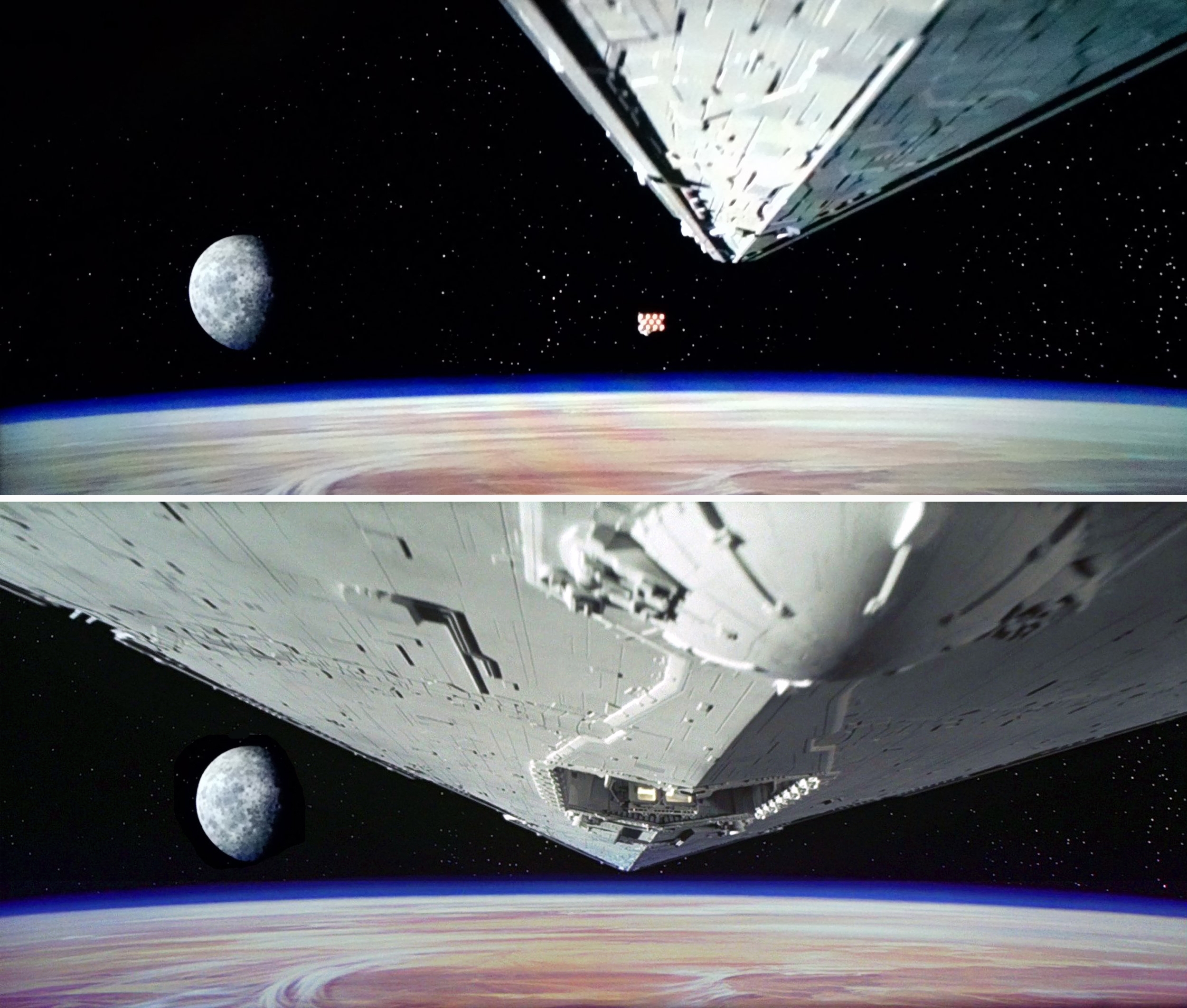

As first cinematographer at the fledgling Industrial Light & Magic, then located within a non-descript building in Van Nuys, Calif., Richard Edlund helped create one of the most famous opening shots in movie history, for Star Wars: Episode IV — A New Hope: the jaw-dropping image of a gargantuan Star Destroyer spacecraft bearing down on a tiny Rebel Blockade Runner ship. “George Lucas had a fantasy of building a fantastic miniature on the stage wall,” he recalls. “I explained how big the Star Destroyer model could be — we only had a 42-foot track for our motion-control camera — and I’d been thinking about this shot a lot. I knew if the audience didn’t buy this shot, the picture would be in trouble. I told George I had an idea and asked him to let me try a test.”

Edlund and assistant Doug Smith set up the shot using the wedge-shaped, 40" Star Destroyer model, tricked out by Grant McCune’s miniature builders, positioned belly-up beneath the Dystraflex motion-control rig so it could be shot upside-down. “I asked Grant to make a quick and dirty Rebel Blockade Runner model about three inches long. I stuck a paper clip on that and stuck it on the nose of the Star Destroyer. We leveled the Star Destroyer so the camera could pull straight back with a 24mm Nikkor prime, and I tilted the lens — like on a view camera — to extend the depth of field. There weren’t any out-of-focus shots in Star Wars — the stars were always needle-sharp in the backgrounds.

“There were times when the lens was scraping the surface of the Star Destroyer. I calculated how long the shot should be, skimmed it with light, and shot a test. The next day, we were flabbergasted, because it worked. George was very happy. I did two or three more takes at different speeds to satisfy him, and that shot became iconic.”

— Joe Fordham

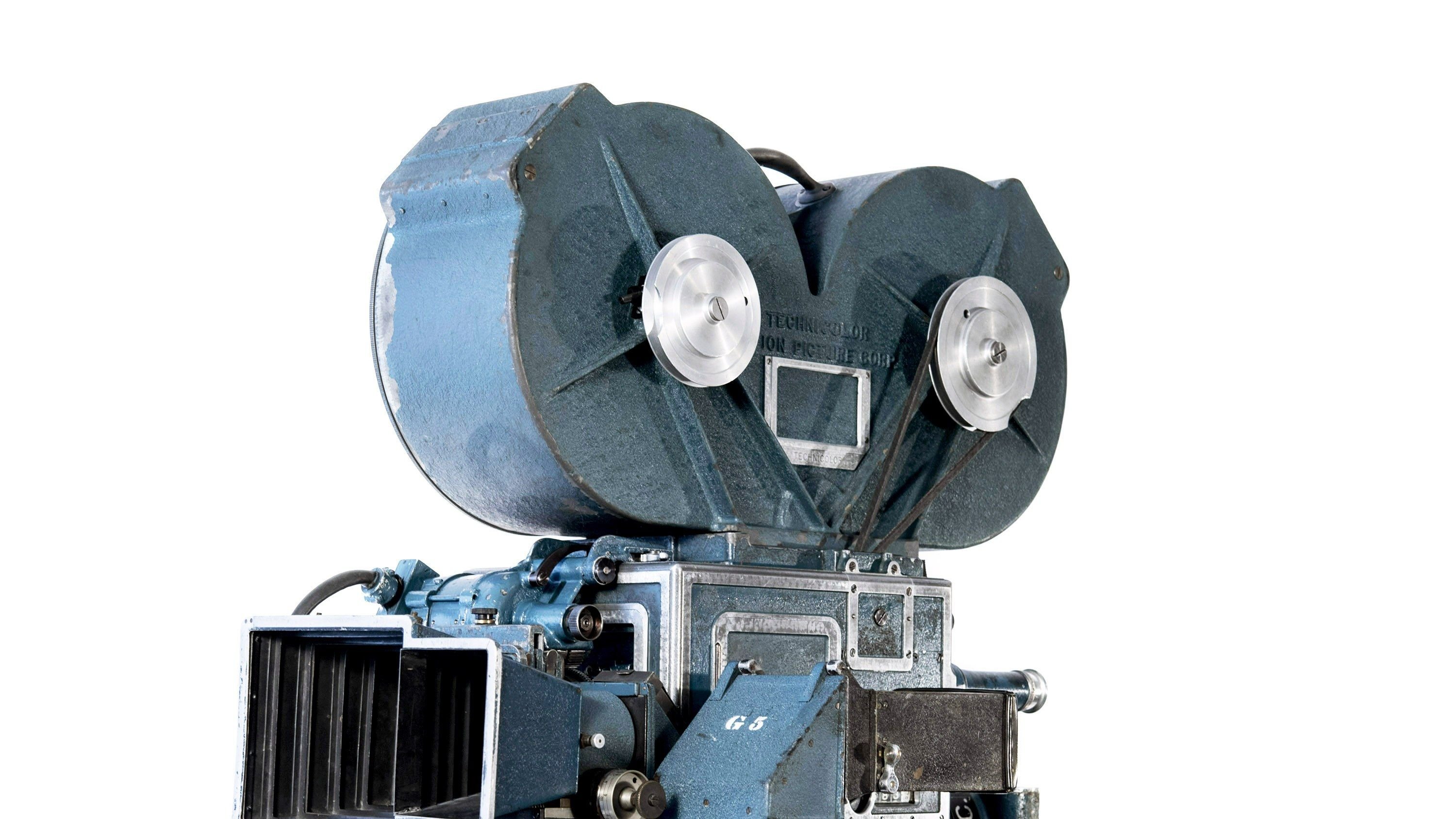

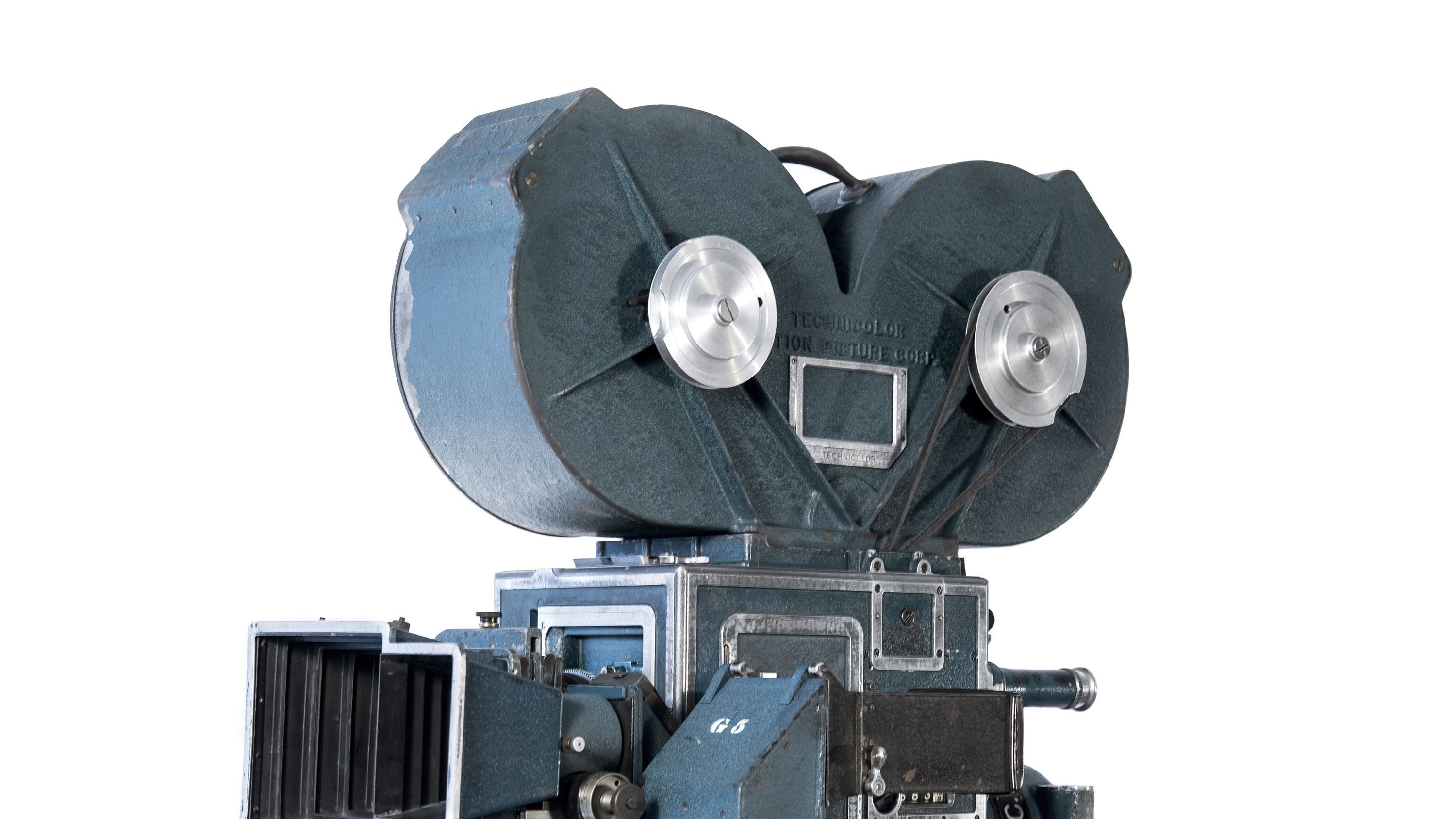

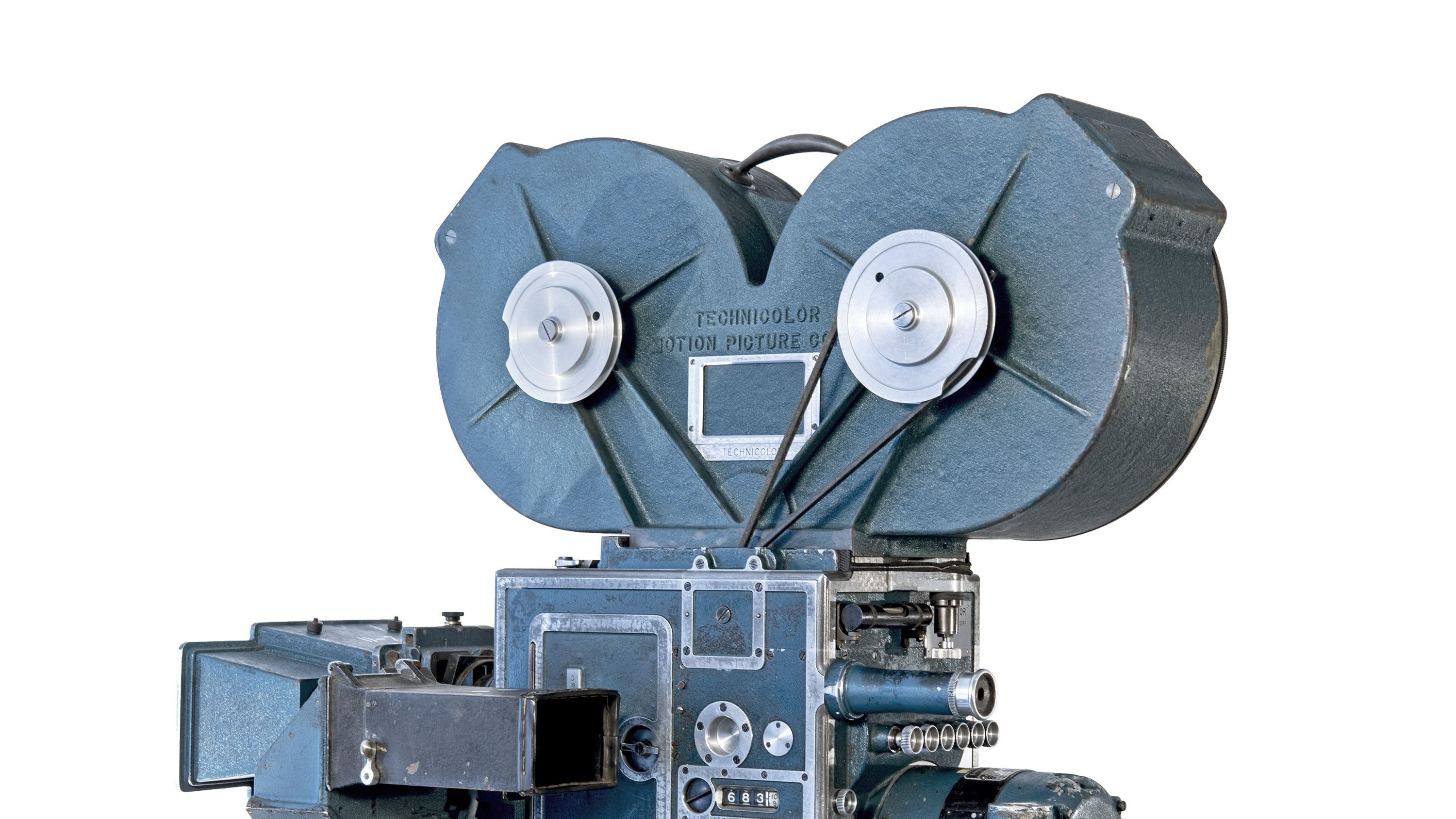

Technicolor 35mm Three-Strip Camera

“That’s the one that I swiped the movement from to make [the VistaVision] unit for Star Wars,” says Edlund. “One of the pitfalls of being a collector is you get to thinking, ‘That’s just too good to throw away!’ So I kept its empty carcass for decades.” He later obtained a replacement three-strip movement from retired Technicolor archivist Merlin Thayer and restored it.

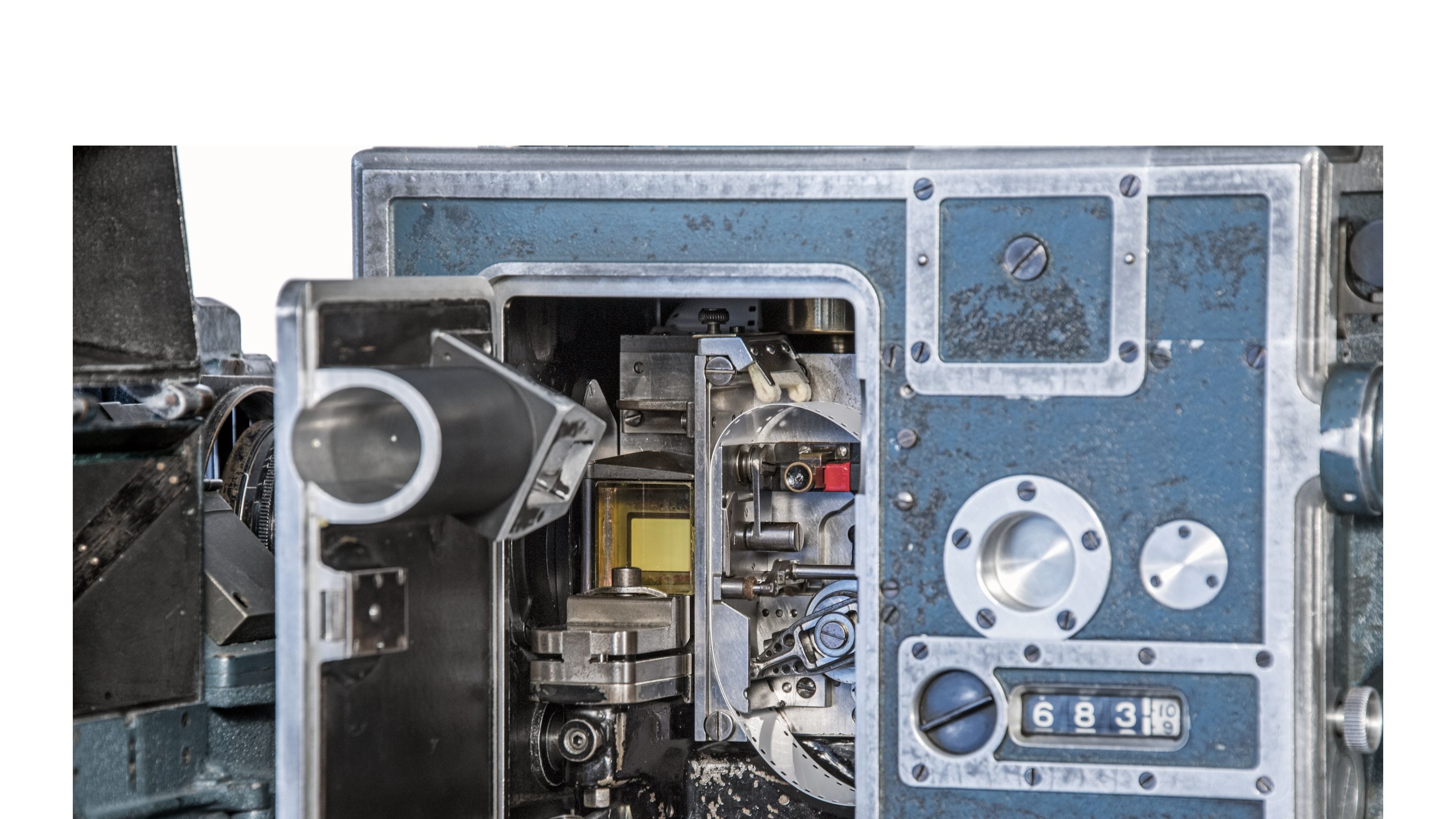

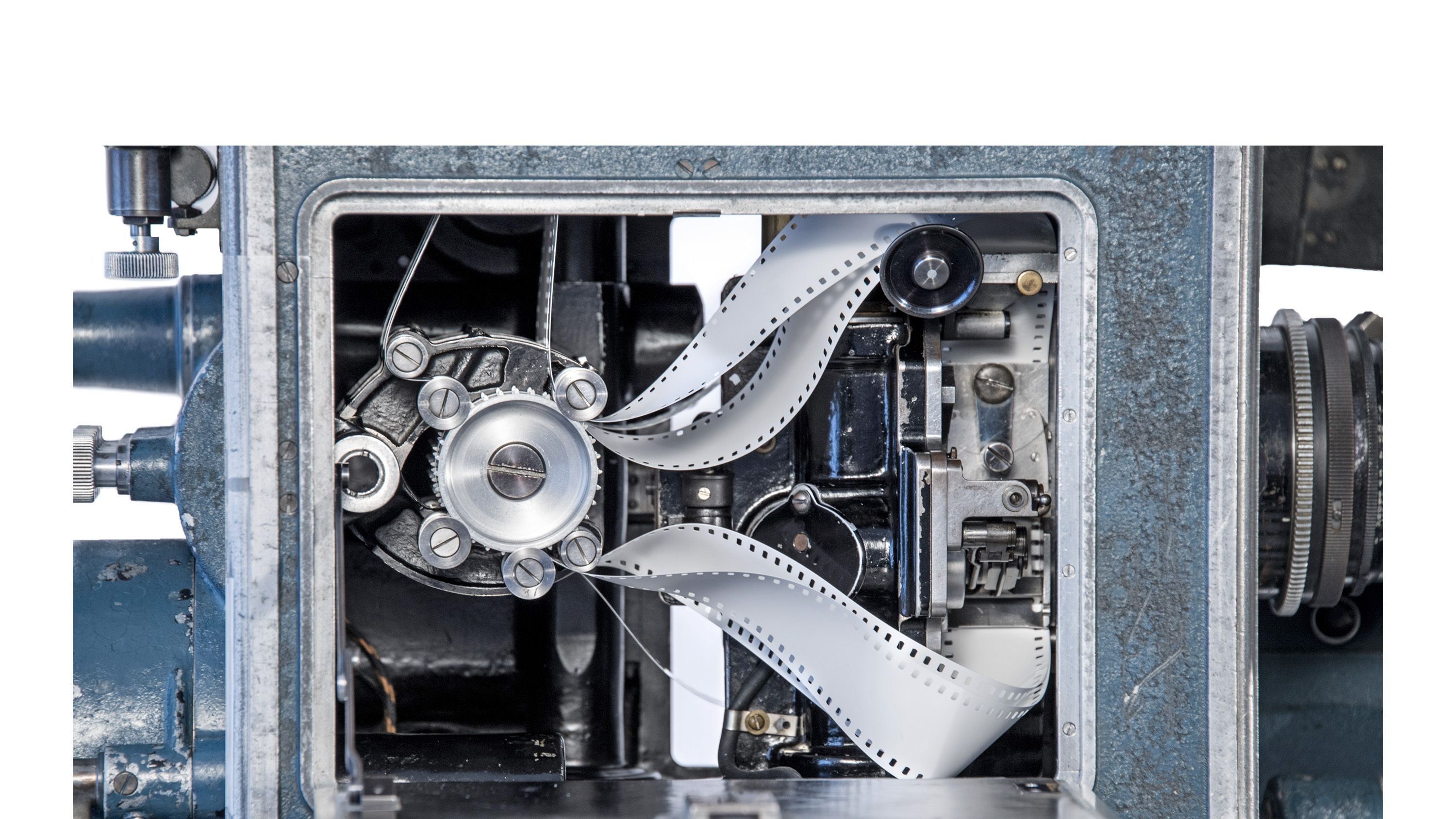

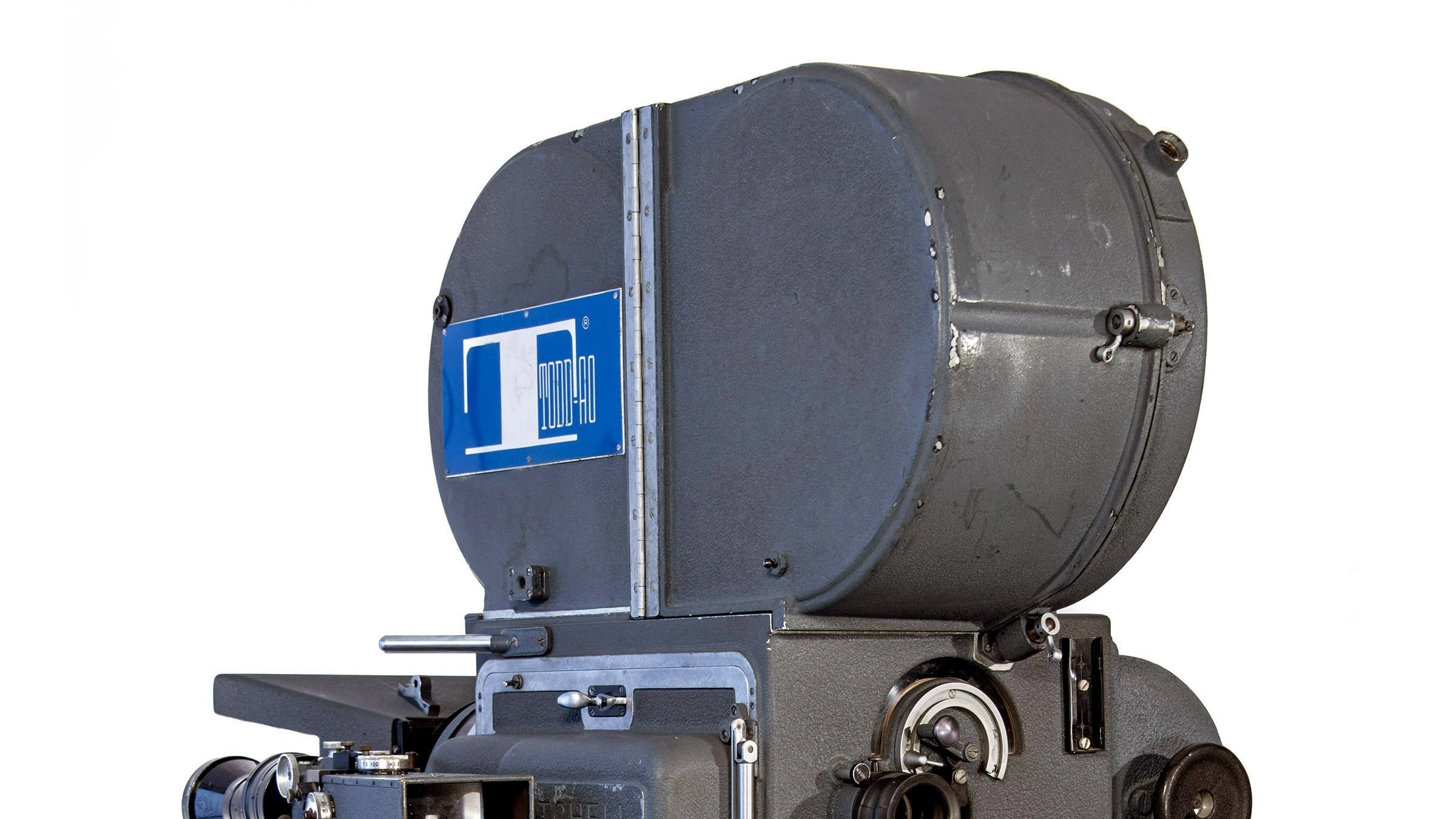

Mitchell 65mm Blimped Fox Camera (BFC)

This unit was built for producer and Todd-AO impresario Michael Todd in 1956. “I have a picture of this camera on the slate from The Sound of Music,” says Edlund, “and I have a picture from the set of Cleopatra with its lenses in the foreground, so we know it was used on those films.”

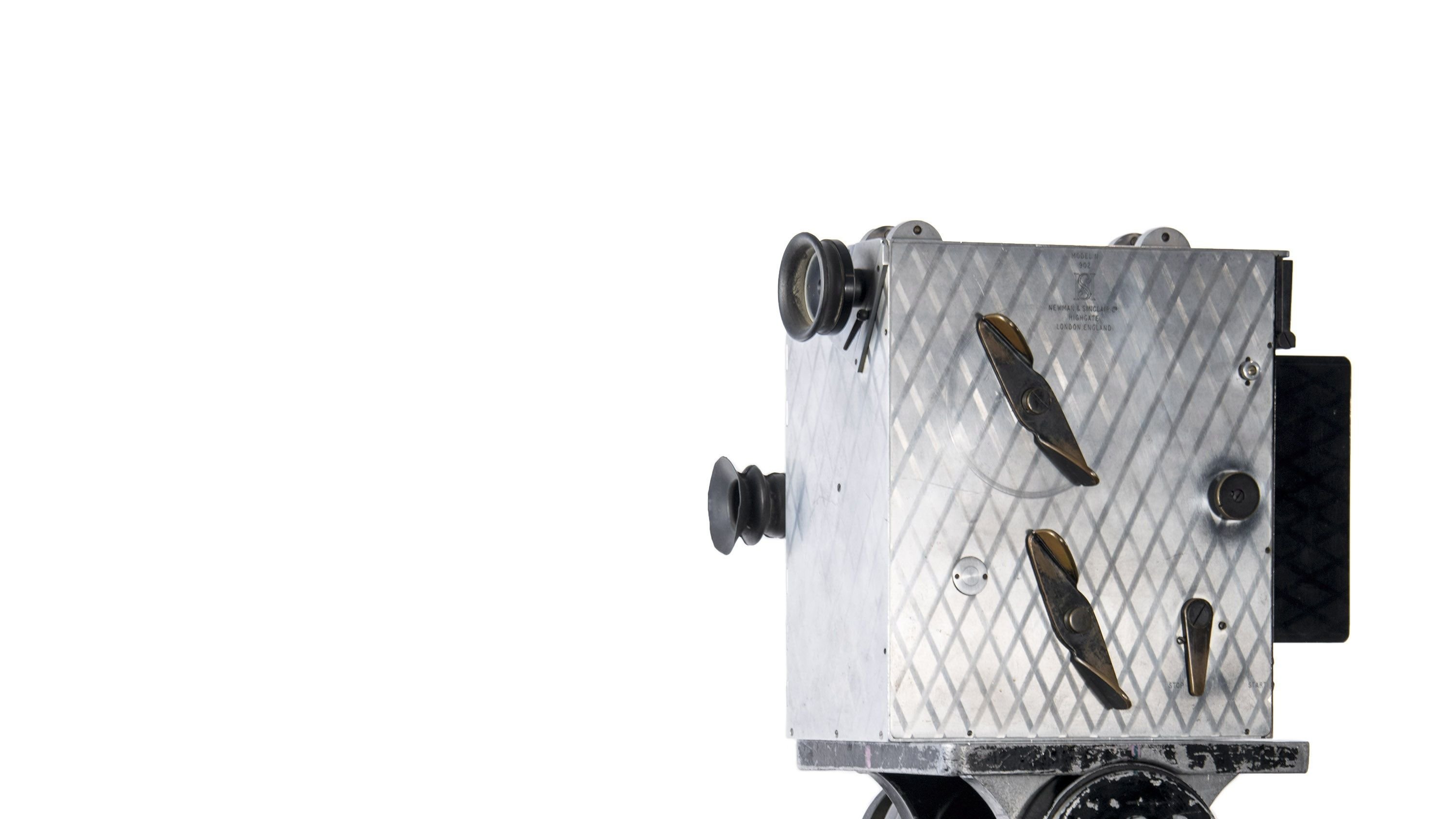

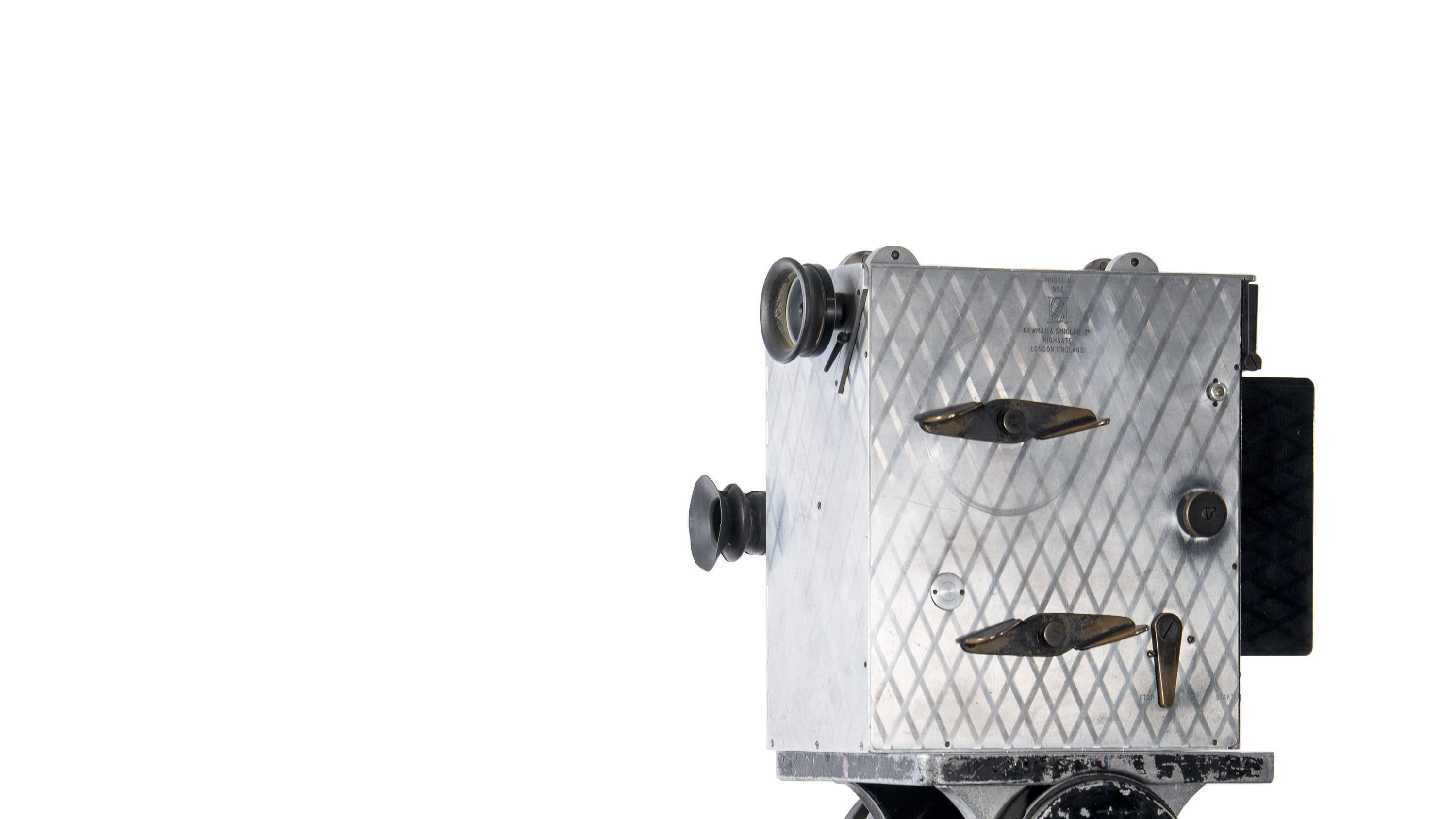

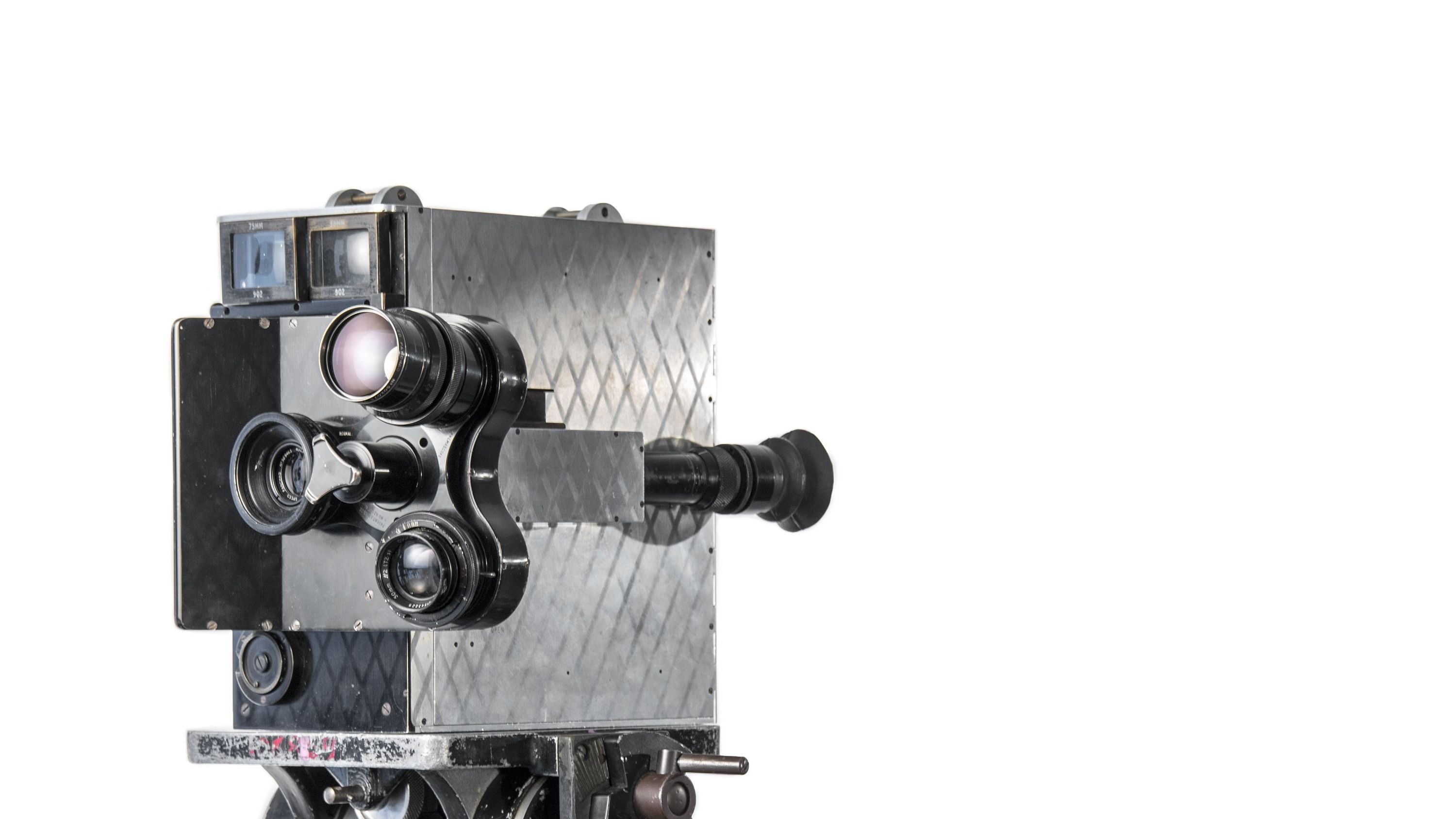

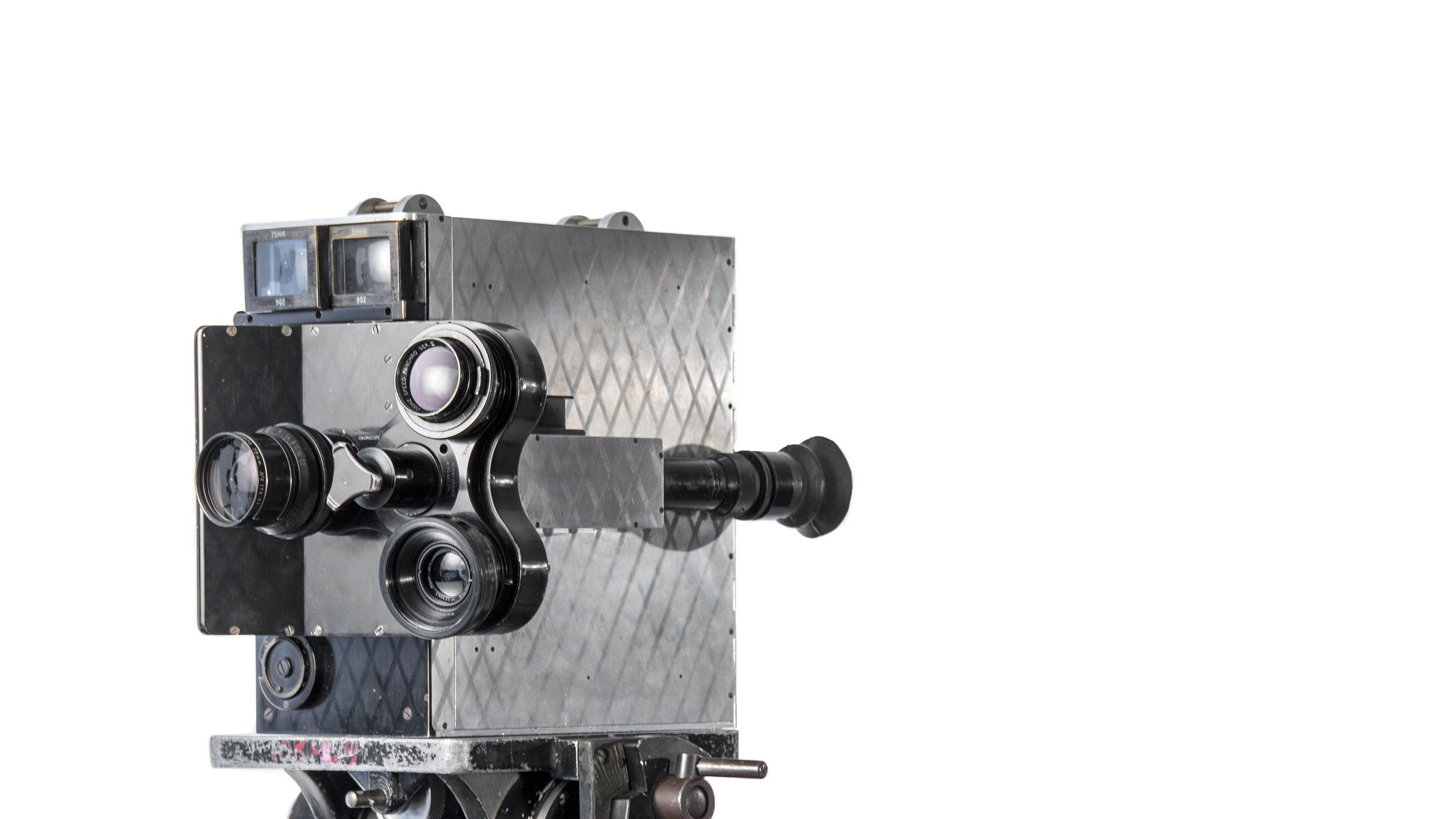

Newman-Sinclair 35mm Reflex Camera

With its raw duralumin metallic finish, this unit has a distinctive style. Manufactured by the Newman & Sinclair Company in London starting in 1927, it features an internal 200' magazine, a variable shutter that can be adjusted to create in-camera effects, and a direct-view optical viewfinder. Lightweight, this spring-wound camera was popular with documentary filmmakers of the day. This unit once belonged to Paul Ivano, ASC.

Stein 35mm Nature Color Camera

Built by the New York-based firm Wm. P. Stein & Co. in the 1920s, this unit was commissioned by studio head William Fox. The Fox “Nature Color” process employed red and green records simultaneously captured on black-and-white film and then composed in post to result in a two-color image. Some of these cameras were adapted in the 1950s to shoot 8-perf VistaVision.

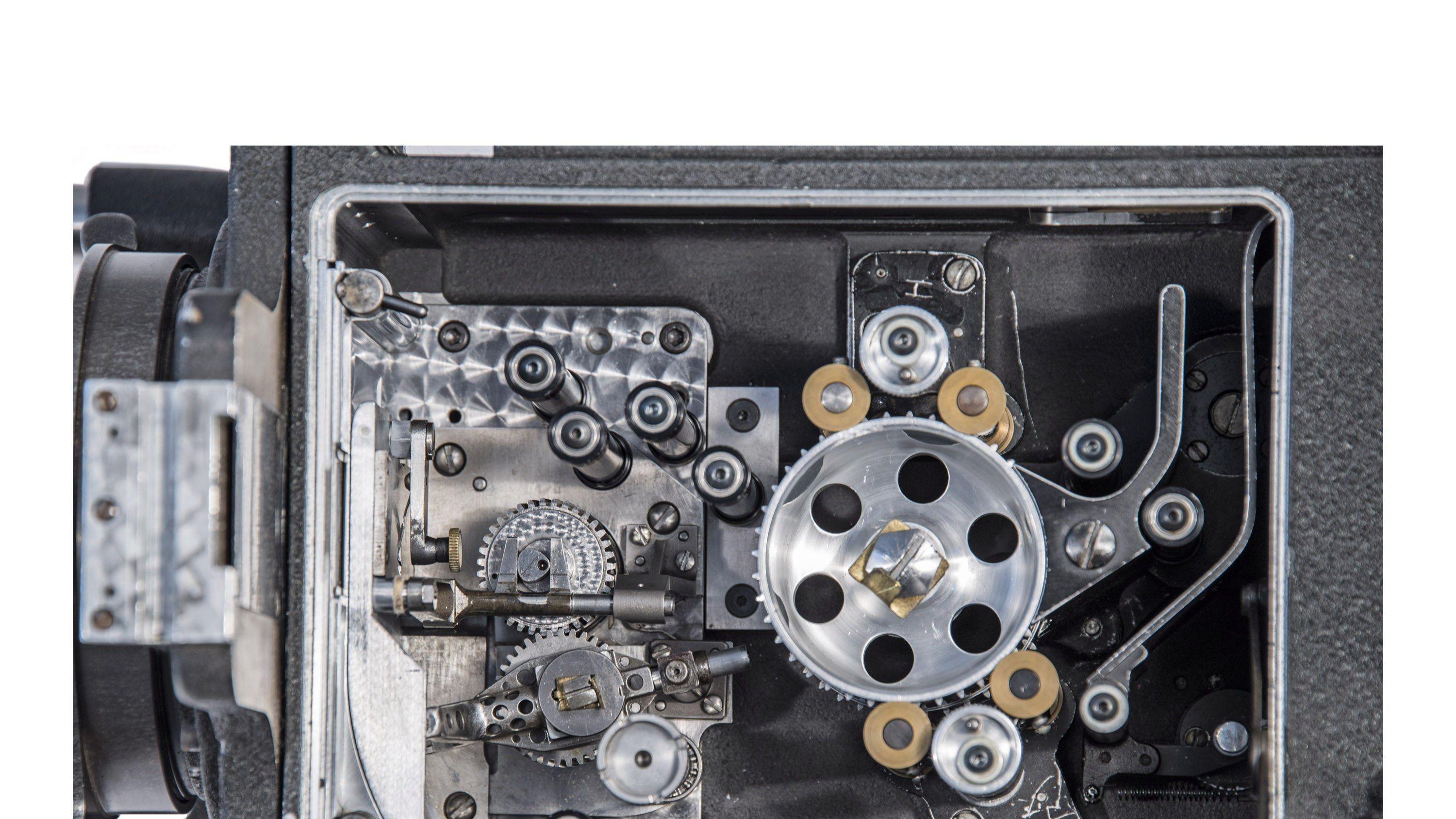

Mitchell 35mm GC High-Speed Camera

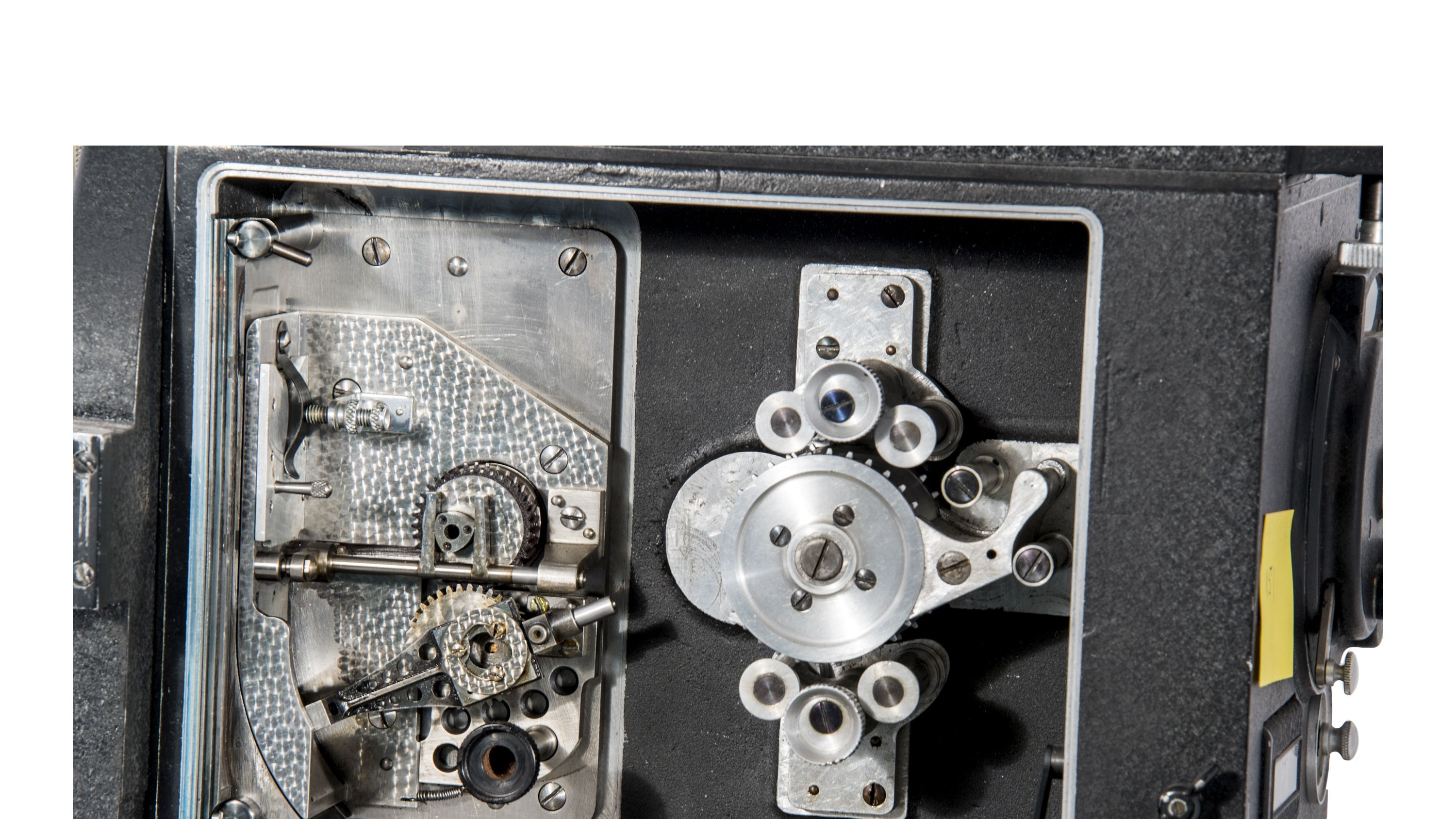

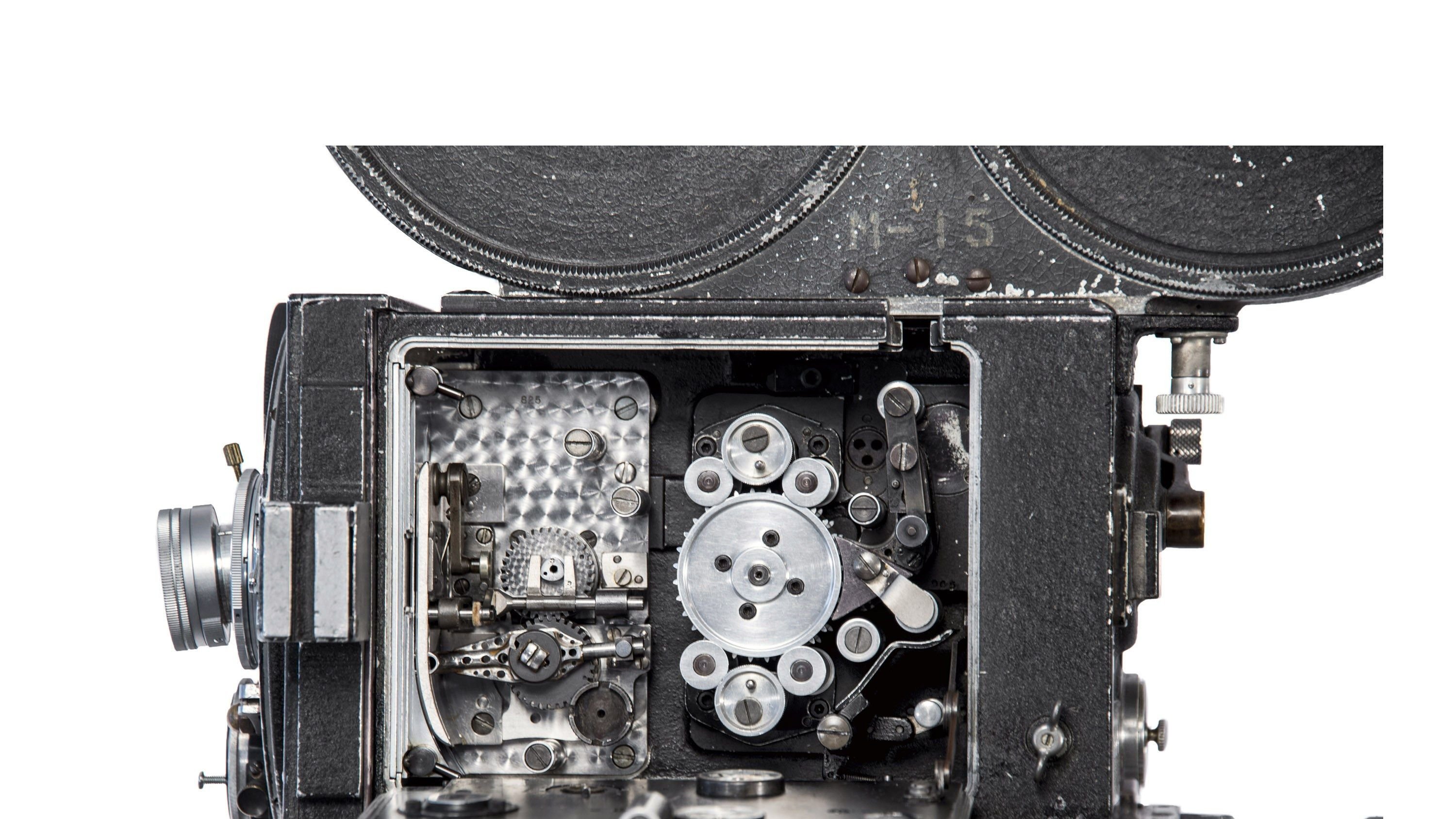

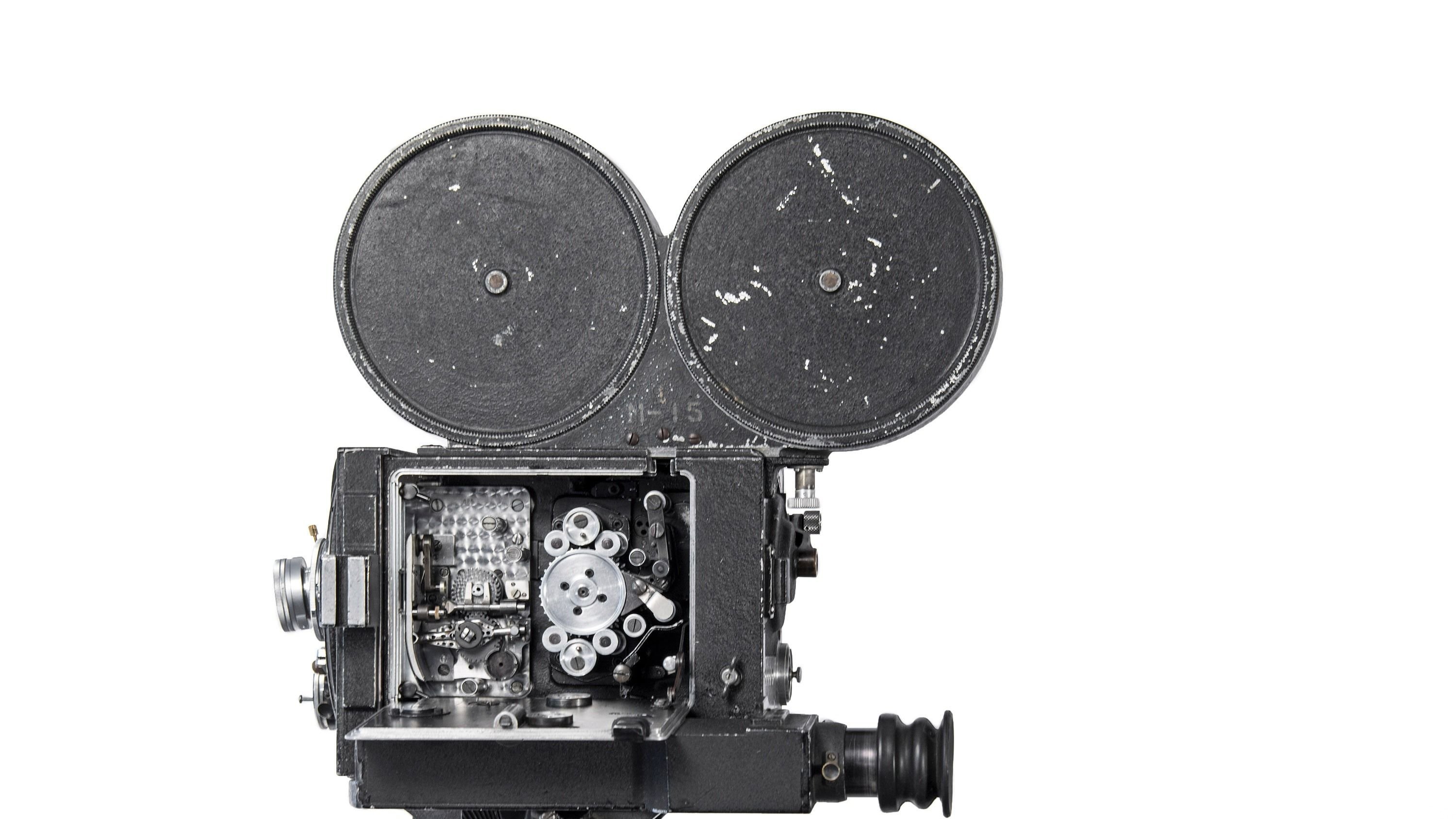

This was a mainstay of the visual-effects industry for many years. The “GC” stands for “Government Camera” as this no-frills model was designed for the U.S. military and built to withstand extreme use.

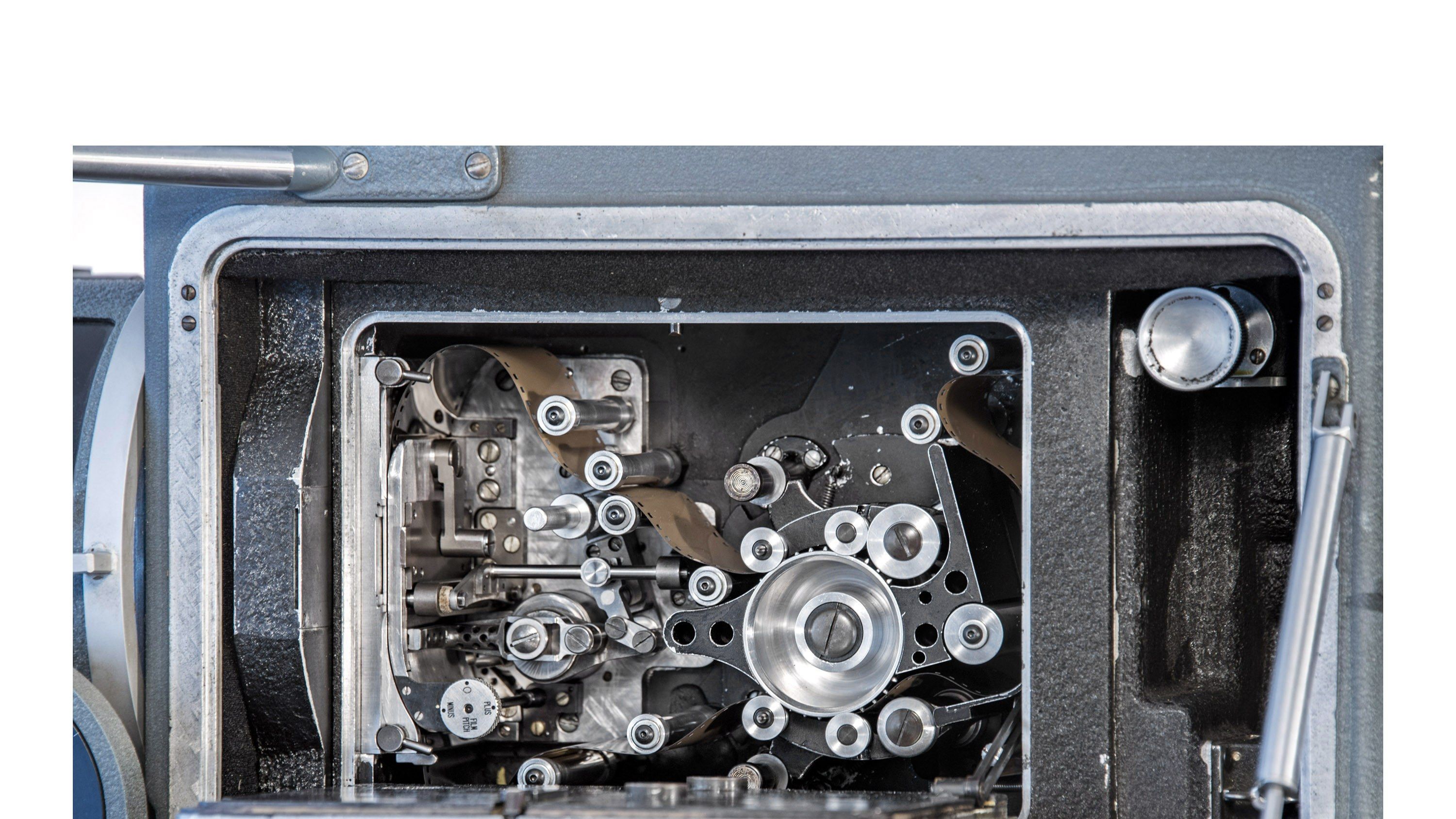

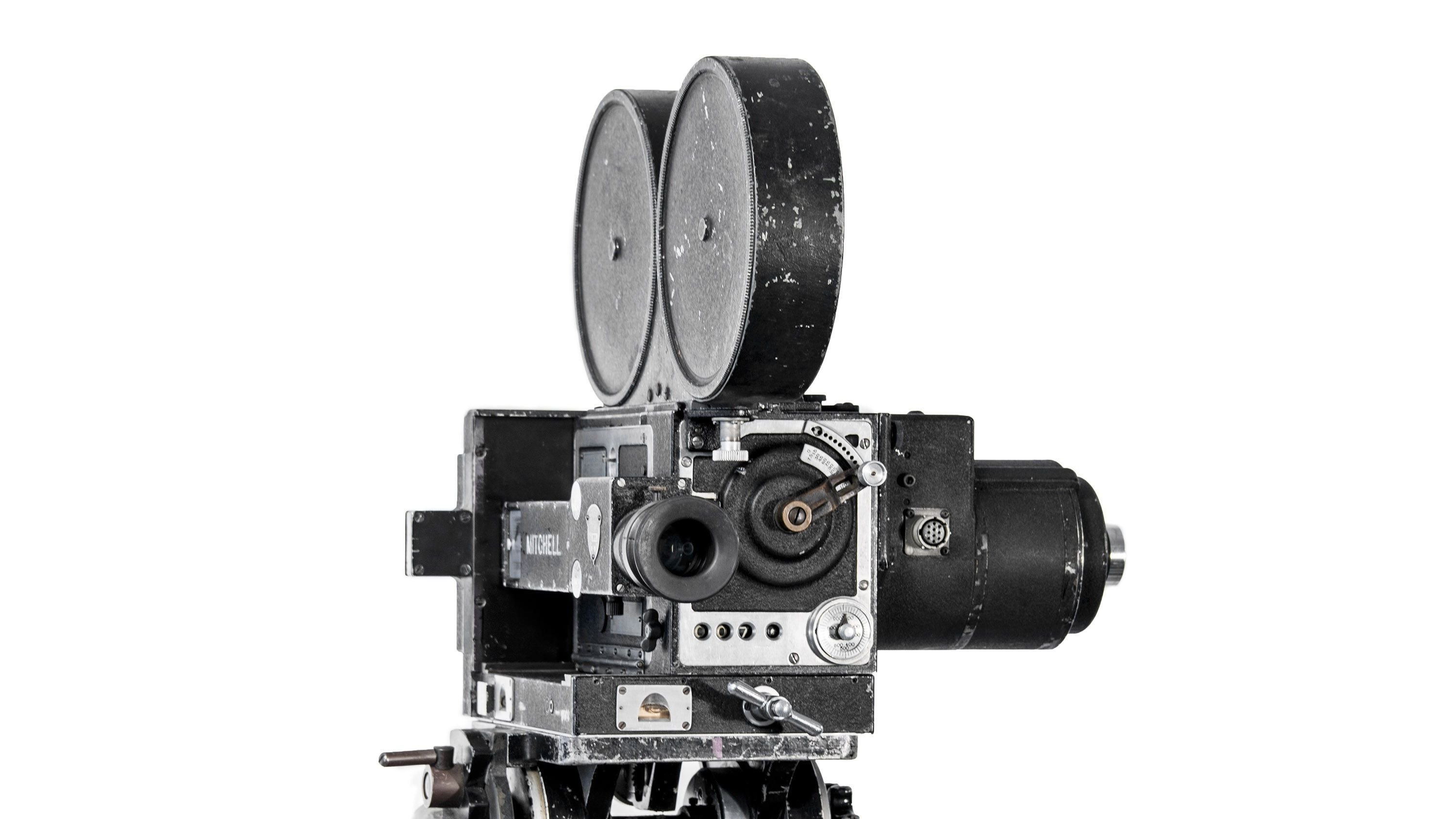

Mitchell 65mm Fox Camera (High-Speed - 100 fps)

“In 1993, I bought the high-speed No. FC-6560 from Claude Chevereau in Paris,” Edlund says, referring to the French rental-house owner. The single-lens unit was intended for visual-effects use at his company, Boss Film Studios.