Shadows of the Psyche: The Conformist

Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC’s imagery in this influential film remains a pinnacle of cinematographic panache.

Edited by Stephen Pizzello

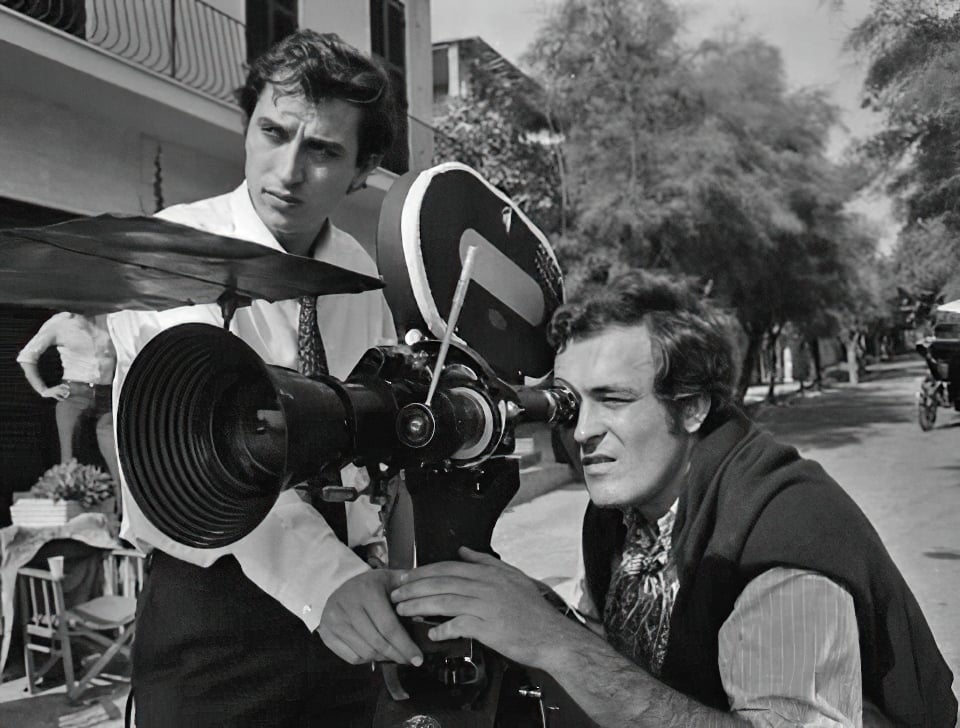

Like Citizen Kane or The Godfather, The Conformist (1970) is a milestone in the history of motion-picture photography. The stunning visuals are the result of a true collaboration between two master filmmakers: director Bernardo Bertolucci, who contributed artful compositions and camera movement, and cinematographer Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC, who amplified the story's themes with his exquisite and emotionally eloquent lighting.

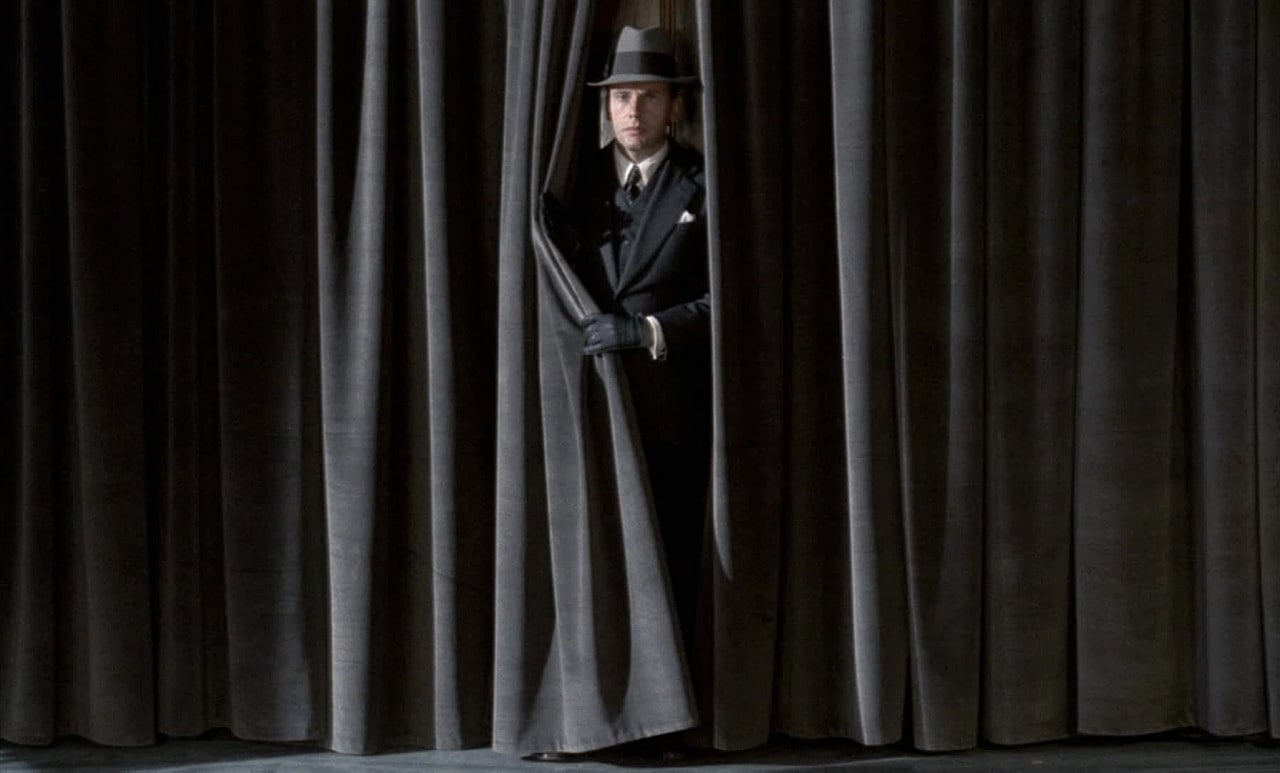

Set in Italy during 1938, The Conformist focuses on Marcello Clerici (Jean-Louis Trintignant), a Fascist flunky with a psychologically troubling past. During a childhood encounter with a homosexual chauffeur named Lino (Pierre Clementi), Clerici shoots and seemingly kills the man. Riddled with guilt and terrified that he'll be exposed as a murderer and a homosexual, Clerici strives to escape into complete conformity by joining the Fascist party and marrying an utterly bourgeois woman (Stefania Sandrelli). When the party asks Clerici to prove his loyalty by killing his former college professor, a political dissident named Quadri (Enzo Tarascio), he is forced to confront both his inner demons and his true nature.

“In a way, The Conformist was my passport to Apocalypse Now, and all of the films I’ve done since then.”

— Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC

Scripted by Bertolucci from the novel by Alberto Moravia, the film has only gained in stature over the years — particularly among cinematographers, who revere it as one of their art form's towering accomplishments.

AC conducted a roundtable discussion about the film with Storaro at the ASC Clubhouse in Hollywood. Heading up the questions were John Bailey, ASC — who cites The Conformist as the film that has had the most indelible impact upon his career — and AC executive editor Stephen Pizzello. Also on hand for the session were fellow cinematographers Stephen Burum, ASC and Dante Spinotti, ASC, AIC, as well as AC associate editor Douglas Bankston.

After analyzing The Conformist, the group took a brief dinner break to enjoy some exceptional Italian cuisine provided by the L.A. trattoria Farfalla; following dessert, the discussion turned to another of Storaro's best-known films, Apocalypse Now.

Stephen Pizzello: Before we start, I'd like to ask John to share some of his thoughts about The Conformist and why it's such a seminal film.

John Bailey, ASC: The Conformistis an epic film, but in a very intimate and finely faceted way. One of the things that's always amazed me about the picture is that even though it deals with an incredibly turbulent period in Italian and European history — a period of thwarted hopes and cultural disintegration — it’s primarily the story of one man in crisis, a man who's trying to find his true identity. In the existential sense, Marcello Clerici is an outsider, and the film is clearly influenced by the philosophies of Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre. Very early on in the film, we see that Clerici comes from a decadent family and is very actively trying to reinvent himself by marrying Giulia, a woman whom he describes as being 'petit bourgeois' and even 'mediocre.'

When you consider a lot of the really great films in the history of cinema, many are about one person, a hero or anti-hero, who is cast against a background of tremendous conflict. In Lawrence of Arabia or Citizen Kane, for example, we see individuals attempting to define themselves within that type of context.

The narrative structure of The Conformist — the way in which the story unfolds — is also fascinating. Back in 1970, although most of us had already seen films by Godard, Renais and other innovative directors, it was still a bit difficult to follow the nonlinear narrative flow of The Conformist, with all of the flashbacks within flashbacks. In fact, the film starts at the very end of the story, with Clerici in the back seat of a car as he's on the way to assassinate his former teacher, Professor Quadri. In the first 20 minutes or so, there are many shots of the driver, Manganiello, while Clerici recalls all of the events from his life that have brought him to this point.

Another thing that I find so striking about the film is that it really exemplifies Vittorio's philosophy of light as a journey of discovery. In The Conformist, there's a connection between the human dynamic and the way Vittorio uses light. Light is very often an active element in the narrative — whether it's light and shadows moving up and down a wall; the hanging lamp that swings between Clerici and Manganiello as they talk in the back room of a Chinese restaurant; or the huge spotlights sweeping across the city at the end of the film, when Clerici sets out to meet his friend Italo on a bridge. The use of light is particularly dramatic during a key scene in which Clerici and Professor Quadri meet in the latter's office. The two of them reminisce about a class when Quadri discussed the myth of the cave, in which figures standing in front of a fire can't see reality in front of them, but only the shadows cast on the wall — the simulacrum of reality.

This afternoon I came across a quote from the book Bernardo Bertolucci [Oxford University Press, 1985], written by film scholar Robert Phillip Kolker. Although he's referring to the scene in Quadri's office, I think what Kolker says is true of the whole film: 'The Conformist is a film about lives lived in the shadows — about shadows that seek other shadows.' The play of shadows is a particularly crucial element of the film's visual style, as is the juxtapositioning of shadows and darkness in terms of character and drama.

Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC: You've actually touched upon a key aspect of my relationship with Bernardo Bertolucci — not only cinematically, but also personally. One day when we were doing The Spider's Stratagem [ 1970], we were filming a sequence in which the main character discovers that his dead father, who has been deified in a small Italian town as an anti-Fascist hero, actually betrayed his friends by telling the police about their plot to kill Mussolini. In a flashback, we see his father's anti-Fascist friends take him to a tower overlooking the city, where they plan to kill him. But in a final attempt to redeem himself, he tells them that they should instead stage his murder in public, in a way that will make it seem as if he was really killed by the Fascists; this will immortalize him as a hero, and ensure that the people of the town will continue to oppose Fascism.

When we arrived at the location in Sabbioneta to shoot the sequence, I found myself lost technically. We were up on a tower in bright sunlight, and all I had was one Sun Gun to light the actors. I thought that no matter what I did, the scene would look terrible. So I asked myself, 'Why should we see this man? He's becoming a symbol, so why don't we transform him into a silhouette?' Of course, let me be honest here: part of the reason I tried to convince Bernardo to shoot the scene that way was because I had no light! [Laughter.] I told him we could shoot the first part of the scene normally, lighting the actors with the Sun Gun; then, when our protagonist walked toward the sunlit view of the town, we would turn off the light and transform him into a silhouette, in a way that would make our intention for the scene perfectly clear. By shooting the scene that way, I was able to symbolically represent the unconscious of the protagonist, and at the same time visually represent the way Bertolucci is telling the story — from the unconscious side.

Bernardo was so enchanted by the idea that I think it was a big reason that I went on to shoot so many films with him. In every film that he's directed, he's never told the story in a completely linear or 'conscious' way. Some aspects of the stories are clearly revealed, while others remain hidden. Certain things are merely suggested, so you have to interpret the meanings and read between the lines. The reason for that stems from Bernardo's life; when he was young, he experienced a major crisis that led him into psychoanalysis, and he's never stopped going. As a result, he's very knowledgeable about the human psyche — not only in terms of the technical theories set forth by analysts like Freud and Jung, but also in terms of the inner soul. Because of that, he always needs to tell stories on both the conscious and unconscious levels at the same time. Of course, I didn't realize then that this particular shot would create such a link between Bernardo and me. I did the scene that way because I couldn't light it in a normal way, and I had to come up with an idea that I could justify philosophically.

Pizzello: How did you interpret the main theme of The Conformist when you discussed the project with Bertolucci?

Storaro: The Conformist is a good picture not only because Bernardo is a great director, but because it has its own life — it's not just a literal translation of Alberto Moravia's book. The film's main concept is not actually written in the book, but you can understand this feeling when you read it. Bernardo took the essence from the book and created his own story.

In the film, when Marcello Clerici is a boy at the age of puberty, he has an encounter with a homosexual chauffeur named Lino. He doesn't fully understand what's happening, and at one point he takes a gun and accidentally shoots Lino, who falls on the floor. From that moment on, in his unconscious, Clerici believes that he's a murderer. In addition, he becomes confused about his sexuality, because while Lino is a man, he has an obviously feminine quality. When you're young and something like that happens, you try to hide what you are because you're not ready to face it. And what is the best way to hide the fact that you're different? To become a conformist — as much like everyone else as possible. That's why Clerici wants to marry the most common woman he can find, someone who's 'all bed and kitchen.’ It's also why he always turns his head to look at other women; he wants to be like everybody else, and that's the most common way to be a man. If you take this logic further, what is the best way to be a conformist in 1930s Italy? To be a Fascist. And if you want to hide even more, you become a Fascist operative who tries to inform on the anti-Fascists. Clerici wants to find the darkest corner in which to hide. One of the film's key moments is when Clerici is visiting his fiancee's family. Her mother tells him they've received an anonymous letter for him, and he goes pale. He's terrified that they've discovered who he really is, but when the mother reads the letter, it explains only that his father is in the hospital; at that moment, Clerici makes a little gesture of relief that really reveals his character.

Pizzello: What inspired the film's visual design, which makes such extensive, symbolic use of Fascist architecture?

Storaro: At first, Bernardo thought he should hire an older cinematographer to shoot the movie — someone who had actually been making movies during the Fascist era. But when we spoke, he realized that the director would then also have to be from that same period! With the confidence that we were both very familiar with the Fascist era through the movies, we thought we could both approach the topic with new eyes.

“I felt that there should be no middle ground between Marcello Clerici and his surroundings; I wanted to create a kind of visual cage around him, using very sharp light and shadows to create a claustrophobic feeling.”

Once I was hired, Bernardo showed me Citizen Kane [1941], a film that we both loved. We also watched The Damned [1969], a wonderful picture directed by Luchino Visconti and shot by Armando Nannuzzi. Afterward, I told Bernardo, 'Those filmmakers did a fantastic job on those pictures, but I think we should find our own way.'

While thinking about The Conformist, I felt that there should be no middle ground between Marcello Clerici and his surroundings; I wanted to create a kind of visual cage around him, using very sharp light and shadows to create a claustrophobic feeling. Although we were shooting our interiors on location because Bernardo loved to work that way, we also felt that we should never see any reality beyond the windows. Therefore, we often worked with venetian blinds and tracing paper to obscure the reality outside.

I wanted this visual cage we were creating to be almost monochromatic — I felt that there shouldn't be any color or passion in Clerici's surroundings. I thought it would be too easy a solution to simply shoot in black-and-white, and that we should find our way in color. We were searching for some way to dramatize color, because at that time everybody thought that color was for comedy, and black-and-white was for drama.

Once Clerici leaves Rome to go on his honeymoon in Ventimiglia and then his mission in Paris, I thought we should open up this visual cage, make the light much more soft, and show more colors. This transition begins with the sequence on the train, where we used rear projection beyond the windows of the passenger car occupied by Clerici and his wife. That journey from Rome to Ventimiglia actually takes half a day, but we show it in two minutes in a series of rear-projection dissolves. The scene progresses from the morning to the afternoon, which is completely orange, and then to the evening, which is blue.

Later, when the characters are in Paris, you see a complete saturation of this blue color. For Italians of that era, Paris represented freedom, and while I didn't really understand the true meaning of the color blue at that point in my career, I felt that the conflict between natural light and the bluish artificial light at dusk created a vibration that was right for that part of the movie.

“I didn’t have even one day of preproduction, and we were often looking for our locations while we were shooting.”

I told Bernardo that I thought we should do all of our Paris exteriors that way; he liked the idea, but he reminded me that we had to shoot from 9 in the morning to 7 at night. In that regard, my nightmare was the dance sequence at the end of the picture, because the light at that location didn't have the kind of density I needed [throughout the day]. Thank God it was close to Christmas, when it's dark and overcast in Paris. I told the executive producer, Giovanni Bertolucci — Bernardo's cousin — that I needed some neutral gelatin for the windows of the dance hall, but he said it would be too expensive to gel all of those windows. Instead, I asked for only one layer of gelatin that I could pull on and off; I didn't want to change the color of the light, I just wanted to knock the density of the light down. We measured things to find out exactly how many rolls of gel we needed, and I eventually convinced Giovanni that if I had the gel I could shoot more hours! [Chuckling.]

Once we were ready to shoot, I told Bernardo we'd be better off shooting the major part of the sequence after lunch, but he liked to shoot things in order. Thankfully, he worked things out so we could shoot our smaller shots early in the day, and the bigger ones at 4 in the afternoon.

On The Conformist, I didn't have even one day of preproduction, and we were often looking for our locations while we were shooting. In my opinion, however, it's always best to be as well-prepared as possible. Once you have a firm structure in place, you can do little things to enhance the structure if things change on the day when you're shooting. But you should always have that firm structure to fall back on. I've done 44 pictures at this point in my career, and one thing I've learned is that once the actors show up, you start shooting; you don't want to constantly stop to change things, because it breaks the emotional momentum for the actors and everyone else. That's why I love using a dimmer board today; it allows me to make adjustments on the set without consuming too much time.

“When we were preparing to shoot that scene, Bernardo and I knew that it was a very important moment in the film.”

Bailey: Let's talk about that key scene between Quadri and Clerici in the study, because it's just stunning. After the two men have their discussion about reality and the shadows of reality, Quadri reopens a window that Clerici has shut. Clerici is standing toward the wall with his hand up in a gesture that looks like a Fascist salute, and as the window opens, the shadow image of Clerici is obliterated by the light. In that moment, he becomes a man without an identity.

Storaro: When we were preparing to shoot that scene, Bernardo and I knew that it was a very important moment in the film, so we sat down to discuss it. In a way, Plato's myth of the cave is also the myth of cinema. The figures in the cave are akin to audiences today, the fire behind them is like a movie projector, and the people carrying statues, passing in front of the fire and creating shadows on the wall are like the film itself. It's a perfect metaphor for cinema. Quadri uses this myth to tell Clerici that the people of Italy are not seeing reality, just the shadows of reality.

When we arrived at the location a day before shooting, we hadn't yet chosen the specific spot where we would stage the scene. In the room we eventually chose, I noticed that there were two windows. I said, 'Bernardo, this is perfect. At the beginning of the scene, we can have both windows open, and then we can have the characters open and close one of them.’

Of course, I then realized that I would need to place a light source outside, and the room was on the second floor of the house. I knew I would need to erect a parallel in the garden of the house next door, so we had to get permission from the lady who lived there. I was praying that she would let us do it, because if she didn't allow us to set up an arc light in her garden, we wouldn't be able to do our scene. Fortunately, she said yes.

Pizzello: What was your thematic motivation for the moment when Manganiello pushes the hanging light toward Clerici in the back room of the Chinese restaurant?

Storaro: That scene was a return to the visual cage we discussed earlier; although the restaurant is in Paris, I wanted that room to confine Clerici in a way that would recall the approach we had used for the sequences set in Rome. While Clerici is trying to hide in the dark corners of this restaurant, Manganiello tips the light to reveal him. Every time the film's plot returned to Clerici's mission, I wanted to place him back in this cage of darkness and light.

Bailey: I'm fascinated by the way Clerici is positioned and framed throughout the film. Graphically and compositionally, it's clear that he's an outsider. He's constantly shown moving away from the action and the other characters, and the way he stands or gestures is often very awkward — he almost seems like a mannequin who's not completely in control of himself. There's one particularly wonderful shot that occurs just after Clerici walks off an elevator and through a crowd of partygoers. It's very claustrophobic for those few seconds as he passes into the hall; then, when he turns and begins to walk away from the camera, the camera doesn't move with him — instead, it pulls back about five or six feet.

Storaro: Camera movement belongs completely to Bertolucci. From the first time I met Bernardo in the early 1960s, he made it clear that the positioning and movement of the camera was part of his directorial grammar. In Italy at that time, it was also generally accepted that camera movement was the director's responsibility; likewise, it was equally accepted that cinematographers were in charge of the lighting.

It's not always like that with every director, however. Working with Bernardo is the opposite of what it's like working for Francis Coppola, who gives you a great deal of freedom. With Bernardo, you are always free to tell him that you don't completely agree with the camera movement, but when you suggest a new idea, he will never use it directly; he will always try to find a third solution, and usually it is the best one. Bernardo is a genius with camera movement, and he's probably more aware of the emotional meaning of specific camera moves than most other directors; therefore, when it comes to camera moves, he prefers to find his own solutions — although he always asks for my opinion.

Bailey: Maybe so, but I've always noticed a distinct difference in the camera style of the films he's shot with you, as opposed to those he's done with other cinematographers.

Storaro: Bernardo was never like other directors, who were simply showing reality in a straightforward way. But at a certain point in Bernardo's career, various critics were accusing him of being too unusual, too unpredictable, too elegant, too refined. Unfortunately, those criticisms had an effect on him. On Luna, I remember him telling me, 'Vittorio, I'd like to see completely into the shadows: He was pushing me to shoot things in a more conscious, straightforward way, which really went against his own artistic philosophy. I always rejected those ideas, and I often fought with him when he wanted everything to be perfectly lit, or perfectly in focus.

Bailey: One shot I particularly love in The Conformist occurs during the sequence in Ventimiglia, when Clerici goes to a Fascist brothel to get his orders for Paris. He arrives in a horse-drawn carriage, and the camera pans left to right toward a building on the seashore, near a promenade that leads to a boat. In the middle of this pan, the camera stops on a painting of this seascape that's resting on an easel. The painting fills the frame, and then there's a dissolve to the real scene behind it.

Storaro: That sequence was inspired by Bernardo's deep appreciation of the French painter Rene Magritte. When we were working on The Spider's Stratagem, he told me he loved Magritte's paintings because they hinted at a life and a universe beyond our own.

For the scene within the brothel, where Clerici is told that he must kill Professor Quadri, we knew we had to do something special. I thought of this beautiful church I had visited in Ravenna that was covered in alabaster, and I decided to surround Clerici with orange, translucent glass.

However, when we finally shot the main scene, in which Clerici receives the pistol with which he is to kill his teacher, I made one of the worst mistakes of my career. I had prepared that room exactly like any other part of the brothel, with tracing paper on the windows and the light coming through. As we did the scene, I realized that the lighting was completely wrong from a philosophical perspective, but I didn't have the courage to tell everyone to stop what they were doing. That was the only scene from my career that I would like to reshoot, because I don't think the lighting creates the kind of tension that the scene needs.

Bailey: Well, I think you're being a bit harsh on yourself, Vittorio, because that scene is still very effective. Another of the film's memorable setpieces is the scene in which Clerici's wife dances in their apartment while wearing a striped dress that matches the stripes of light on the walls — a pattern created by the venetian blinds on the windows.

“The matching of the lighting and the dress happened purely by accident!”

Storaro: I had just begun working on The Conformist when I went to see the house where that scene would be shot. When I had read that scene in the script, I got an idea about how to light it, but when were actually on the set, I only had one arc light. I was begging Giovanni Bertolucci to give me two more arcs, because I was dealing with three windows, but he only got me one more light — for just two days!

Furthermore, the very first time I met the production designer, Ferdinando Scarfiotti, was when we were preparing to shoot that scene! He showed up the following Monday with the striped dress for actress Stefania Sandrelli to wear, so the matching of the lighting and the dress happened purely by accident!

Bailey: Near the end of the movie, Clerici falls asleep in the car as he and Manganiello get closer to the site where they're going to kill Quadri. When he wakes up, he tells Manganiello that he's had a dream that he was blind, and that Quadri appeared as a surgeon who restored his sight. In a sense, he's going to kill the one man who could lead him out of the blindness of his own life and toward some kind of understanding. Earlier in the film, we've also encountered Clerici's friend Italo, who is a blind poet. So there's this theme of the characters being blind that's both literal and metaphorical.

Storaro: The dream is certainly part of the analysis of Marcello Clerici, and it relates back to Quadri's discussion of Plato's myth. In discussing the figures before the fire, Plato is trying to tell people to wake up to reality. They don't want to listen, though, and instead they kill him. So after his discussion with Clerici, Professor Quadri realizes that his former student has been hired to kill him. Like Plato, Quadri is revealing a truth that the people don't want to hear or understand.

After that scene, there's a moment between Clerici and Quadri's wife when she offers him her body and says, 'Please don't hurt us, Marcello: She also knows what he's up to, and as she approaches him and undresses herself, the room turns a very deep indigo. At her core, Quadri's wife is very much like Clerici, and she understands his motivations.

Bailey: Let's go back to the issue of camera movement. Throughout most of the film, the moves are very restrained and tightly controlled. However, in the scene just after Quadri is murdered, when the killers are chasing his wife through the woods, you employ a very frantic handheld camera. I thought that change of tactics was just brilliant.

“After the first take, Bernardo asked me if I’d gotten the shot, and I told him I wasn’t sure.”

Storaro: Before we shot that scene, we were told that there was a storm coming, and that we would have to finish in one day. We had already decided to shoot the sequence in a very violent way, with the camera behind actress Dominique Sanda, but I had no idea that the work would be so complex and physically demanding. I operated a handheld Arri 2-C myself, and Enrico Umetelli was operating another camera that was set up further away with a telephoto lens.

We were originally supposed to shoot The Conformist with the new Mitchell Mark V, but it wasn't ready in time. For the scene in the woods, I used a very small magazine to keep the camera's weight as light as possible, but I couldn't always keep my eye to the viewfinder while I was running — the camera was shaking too much. I was pressing the eyepiece against my shoulder so no light would go through it, and adjusting the camera as I ran after Dominique. As I followed her, three of the men playing the killers gradually ran past me in a line; the last man then tossed a gun to the man in front of him, and I followed the weapon as it passed from man to man until the lead killer finally reached Dominique. She had a little device in her hand so she could rub fake blood on her face when they finally shot her, and after that I followed her as she staggered from tree to tree.

Believe me, at that point I was staggering around, too! I could barely catch my breath, and I thought I was going to die from the physical exertion – you need to do some training before you try to film something like that!

In those days, we didn't have any Steadicam, and the real problem was that I couldn't see through the camera. After the first take, Bernardo asked me if I'd gotten the shot, and I told him I wasn't sure. So of course we had to do it again — after I had rested for about 10 or 15 minutes!

The second time we did it, I felt a bit better, and I think we wound up doing three takes. We finished the last one at the end of the day, and right after we got the equipment back to the cars, the storm arrived.

While we were driving away, I was so high from all of the physical exertion, and so excited to have personally experienced such an emotional sequence, that I didn't even care if I'd gotten the shot on film or not! It was an absolutely amazing sensation.

Bailey: At the very end of the film, Clerici comes face to face with Lino, the homosexual chauffeur whom he mistakenly believed he had killed during his childhood. When he realizes who this man is, he begins loudly denouncing him as a homosexual, a Fascist, a murderer — he basically blames Lino for everything he himself has done.

Storaro: Yes, for Clerici that is the moment of catharsis. When he discovers that Lino is alive, he realizes that he's not an assassin after all, and he finally accepts the fact that he's different not because he's an assassin, but because he's a homosexual. He's completed the journey within himself, and in that moment, he throws all of his [psychological baggage] onto Lino.

Bailey: The lighting during the film's finale really captures the emotional shift that's taking place within Clerici.

Storaro: In that sequence, there's a beam of light that follows Clerici through the street, and when he comes upon Lino, the beam stops on the two of them for awhile. A short time later, this group of people comes along like a river to sweep everything away, including Clerici's blind friend Italo.

When we were preparing to do the very last shot in the film at the Teatro Marcello, I wasn't sure how I was going to light it. I had the crew set up various lighting units, and then I took a walk to smoke a cigarette. While I was walking, I thought about how the incredible journey of this character was going to end during this shot. As I began wondering how I could convey this key moment visually, all of these crew members were bustling around in total chaos. Then, suddenly, I wasn't hearing the crew noise anymore, and I could instead make out the sound of these birds chirping across the nearby river. At that moment, when I heard the sounds of nature amid this incredible chaos, I knew that I had to tum off every light. We wound up doing the scene with just a bit of firelight on Clerici's face.

Bailey: That sequence is wonderfully ambiguous, because you first show the backside of a male prostitute before cutting to a tight shot of Clerici looking almost directly into the camera. You do get the strong feeling that he's come full circle.

Pizzello: Vittorio, can you tell us what kind of impact The Conformist had upon your career?

Storaro: Well, the reason that Francis Coppola asked me to shoot Apocalypse Now — my first American picture — was that he loved The Conformist. So, in a way, The Conformist was my passport to Apocalypse, and all of the films I've done since then.

The Conformist was selected by the ASC as one of the 100 Milestone Films in Cinematography of the 20th Century.

Storaro and Bertolucci were jointly honored for their long collaboration at the Milan Film Festival in 2018.