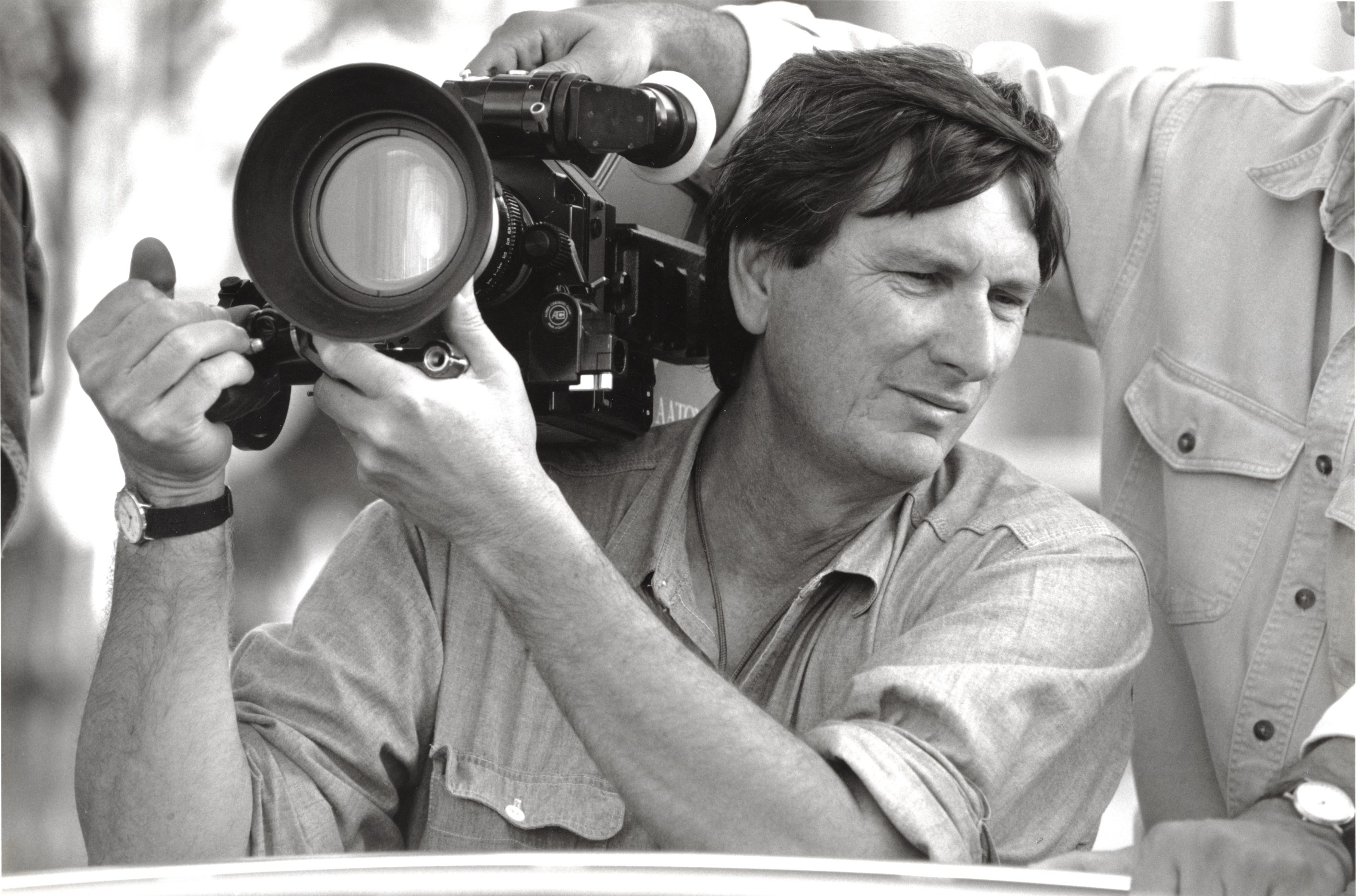

In Memoriam: John Bailey, ASC (1942-2023)

The cinematographer was well-known for seeking humanist screen stories, with his work including Ordinary People, The Accidental Tourist, The Big Chill and As Good as it Gets.

John Bailey, ASC died on November 10, 2023 at the age of 81 following an extended illness, leaving behind both a unique body of work and a legacy of leadership in the motion-picture business.

The cinematographer amassed screen credits that run the gamut from dramas and action to comedies and Westerns. Perhaps because of that variety, his cinematography doesn’t show the stamp of a single cinematic sensibility, but instead reflects as many different approaches as there are credits to his name. “I’ve never read a script to try to find photographic opportunities,” Bailey told American Cinematographer. “I look at the emotional value to see if I’m moved.”

“I did not want to do tawdry films,” he later explained. “I did not want to do exploitive films or violent ones. I really held out, sometimes at great personal expense, literally, in terms of money, to do films that I knew were building a résumé that when I did become a director of photography that that was part of who I was.”

Born on Aug. 10, 1942, in Moberly, Mo. and raised in Norwalk, Calif., Bailey’s background was blue collar, but his parents had an abiding respect for education and did all they could to ensure that their son would have the opportunities they hadn’t.

“Like most kids, I was a sucker for horror and sci-fi films,” he told AC. “Two that scared me to death at an impressionable age were the original The Thing, photographed by Russ Harlan, ASC, with a score by Dimitri Tiomkin, and The Man from Planet X, directed by Edgar Ulmer and photographed by John Russell, ASC. At that age I didn’t have any idea that movies were made; I thought they just sort of happened.”

While attending Pius X High School, Bailey was guided toward college-prep courses. In his senior year at Loyola University, he was accepted to the University of Southern California's School of Cinema. His studies opened his eyes, particularly to the works of filmmakers such as Ingmar Bergman and Michelangelo Antonioni. He aspired to be a film critic.

To critique cinema from a more technical point of view, Bailey enrolled in a cinematography course. One of his first assignments was to shoot a photographic study using a single roll of film. Bailey chose to shoot the routine at a hamburger stand, taking photos as the cook flipped burgers and the patrons ate. With some residual embarrassment, Bailey recalled to AC, "The frames were so overexposed that there was barely an image! I’d misread the meter. I did whatever I could to make prints and brought them to class.”

The teaching assistant happened to be future ASC member Woody Omens. “I was thoroughly chagrined by these photographs, but Woody said, ‘Mr. Bailey here has done something interesting. He has chosen to make it very high-key. It’s almost as if Richard Avedon had photographed a hamburger stand!’ I saw this as a disaster, and Woody put a beautiful, supportive, positive spin on it. Woody is the reason I had the courage to pursue photography."

Upon leaving USC, Bailey found jobs in the camera department on several "zero-budget" films. “Working as a camera assistant, even at the loader stage, was physical work, and I found it to be immensely satisfying.” Then, on the 1971 cult favorite Two-Lane Blacktop, he worked as an assistant under Hungarian cinematographer Gregory Sandor, who taught him about the precision involved in classical cinematography. Another formative influence was director of photography Jimmy Dickson, whom Bailey credits as an essential supporter.

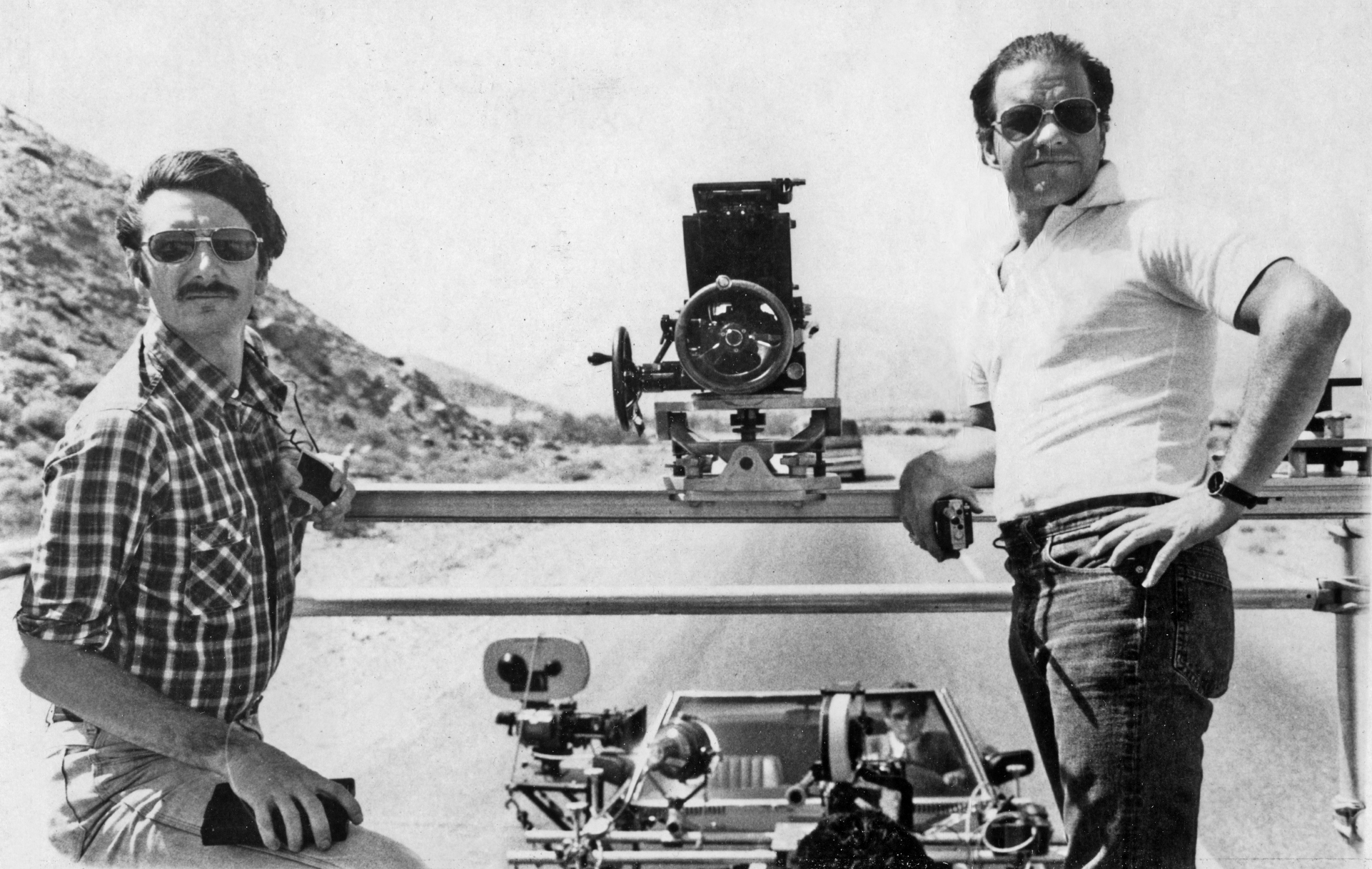

Later, as the camera operator on Robert Altman's 3 Women, Bailey learned about setting an optimistic tone on the set from Charles Rosher Jr., ASC, and while operating for Néstor Almendros, ASC on the period drama Days of Heaven, he observed brilliant applications of single-source natural lighting. Bailey also served as operator on Winter Kills, and credits the anamorphic compositions of that film's cinematographer, Vilmos Zsigmond, ASC, as inspiring his own abiding love for the widescreen format.

After Bailey shot some small features, agent JoAn Kincaid secured him a meeting with writer-director Paul Schrader, who was prepping the stylish, sexy drama American Gigolo for Paramount. A former film critic, Schrader went into the meeting intent on hiring a European, but, impressed with Bailey’s keen knowledge of foreign film — The Conformist, in particular — the director hired him instead.

After the success of American Gigolo, Bailey and Schrader’s fruitful collaboration continued with the highly stylized Cat People, the lyrical Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters, and the emotionally raw Light of Day.

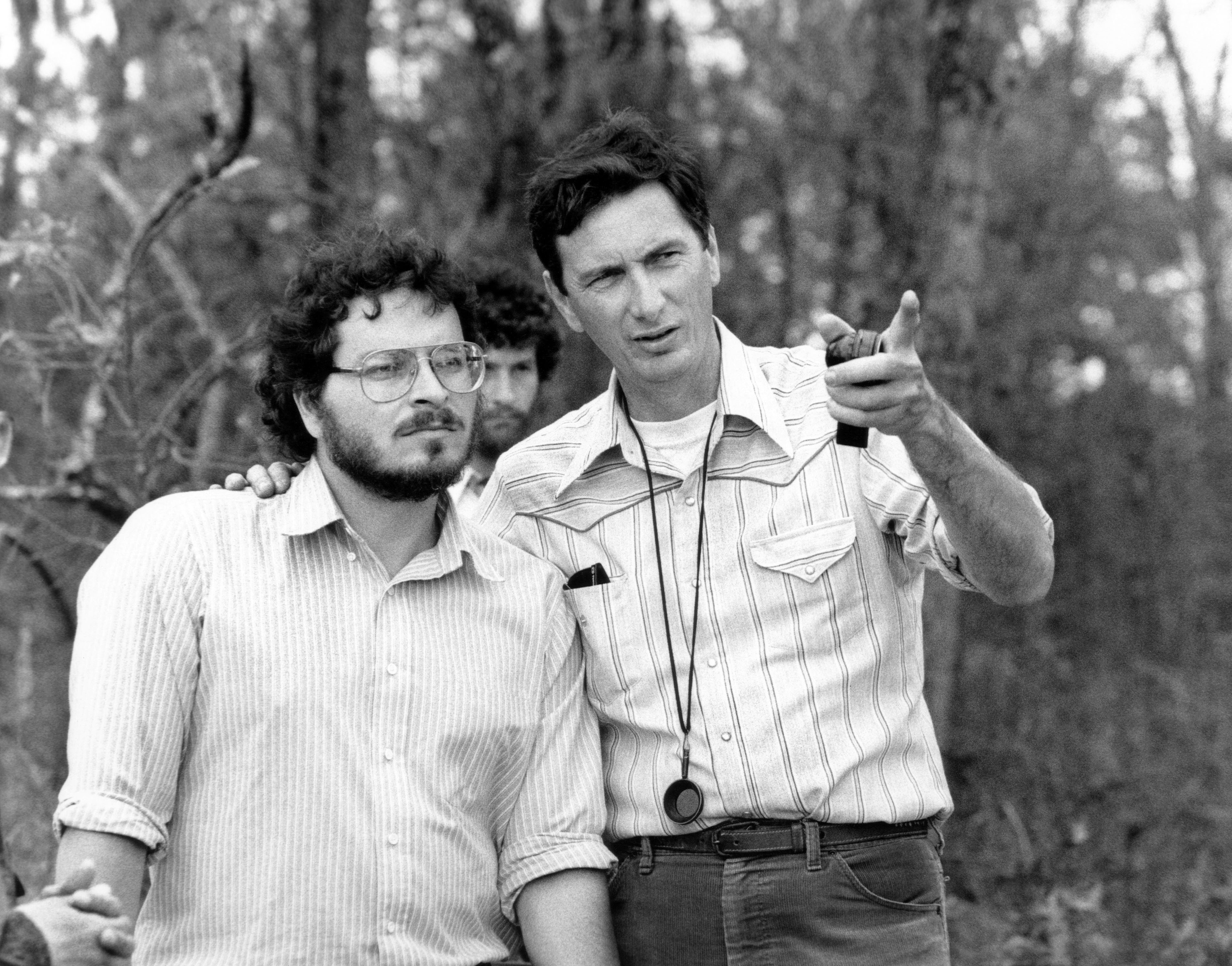

Bailey soon found himself meeting with Robert Redford to discuss his directorial debut, Ordinary People. The cinematographer admits that his understated camerawork in the picture does not have a look that declares itself — nor, he says, do most of his films. While he brought ideas about color and light from his love of painting, he made a decision early on that his cinematography would be only one component of a whole film and not an end in itself. Unless self-conscious stylization was called for, he wanted his work to be “invisible.”

Bailey’s working relationship with writer-director Lawrence Kasdan began with the naturalistic, character-driven drama The Big Chill in 1983 and continued with the larger-than-life Western Silverado. But it was The Accidental Tourist that Kasdan told AC was “my favorite collaboration with John. It’s one of his best movies, and mine, too. John is so sensitive to nuance, and that movie is all nuance.”

Another of Bailey's close allies has been director Ken Kwapis. "My collaboration with him has been the abiding continuity in my career," remarks Bailey. Their 30-year relationship has included six features — from Vibes in 1988 to A Walk in the Woods in 2015.

That same year, Bailey was proud to receive the ASC’s Lifetime Achievement Award, and was delighted when then-Society President Richard Crudo informed him of the honor. “I’m happy that it reflects my whole body of work so far,” he said, “and I’d like to believe it is also a recognition for work I’ve done for the organization, and my writing and teaching.”

Bailey was a longtime member of the ASC Board of Governors and helped guide the Society through several transitional eras, most recently the move to digital capture in the 2000s, serving as an astute student carefully analyzing its evolution and embracing it when appropriate for the story at hand. At the time, when virtually every theatrical feature was still shot on film, he experimented with PAL video using Sony DSR-500 cameras for the improvisational indie drama The Anniversary Party. He then shot the innovative mockumentary Incident at Loch Ness with Panasonic DVX100s.

For many years, his blog hosted on the ASC’s website — John’s Bailiwick — was an ongoing meditation on the creative process in the arts, chronicling the work of not only other filmmakers, but painters, composers, photographers, sculptures, architects, and other practitioners of many crafts that drew his interest.

In 2017, Bailey, a longtime member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and governor in the Cinematographer’s Branch, was elected president of the organization – the first time a cinematographer had held the position in almost 60 years. He was re-elected in 2018 for a second term.

“I had no idea how stressful that job was going to be,” he told AC after this tenure was over. “Part of it is my own fault because I decided to take on some issues that I thought really needed to be addressed, that — particularly regarding international membership and the fact that we had been sitting for decades on an old system where it was almost impossible for non-industry or non-Hollywood people to really get into the Academy because of the limitations of the sponsorship process. So, we changed that. In the last two years, 50 percent of new Academy members were international.”

In 2020, Baily was honored with the Lifetime Achievement Award from the International Film Festival of the Art of Cinematography Camerimage — presented with his honor by actor Richard Gere, who starred in one of the cinematographer’s early breakthrough pictures, American Gigolo (1980), directed by Paul Schrader. (You’ll find an extended interview with Bailey here, discussing this honor.)

Bailey is survived by his wife, noted film editor Carol Littleton. They married in 1972 and had the distinction of working together on films including The Big Chill, The Accidental Tourist and Silverado.

Additional reporting by Jon Silberg