Spartacus: A Spectacle Revisited

A retrospective on the “swords and sandals” tentpole around the time of its restoration for Universal.

This article originally appeared in AC May, 1991

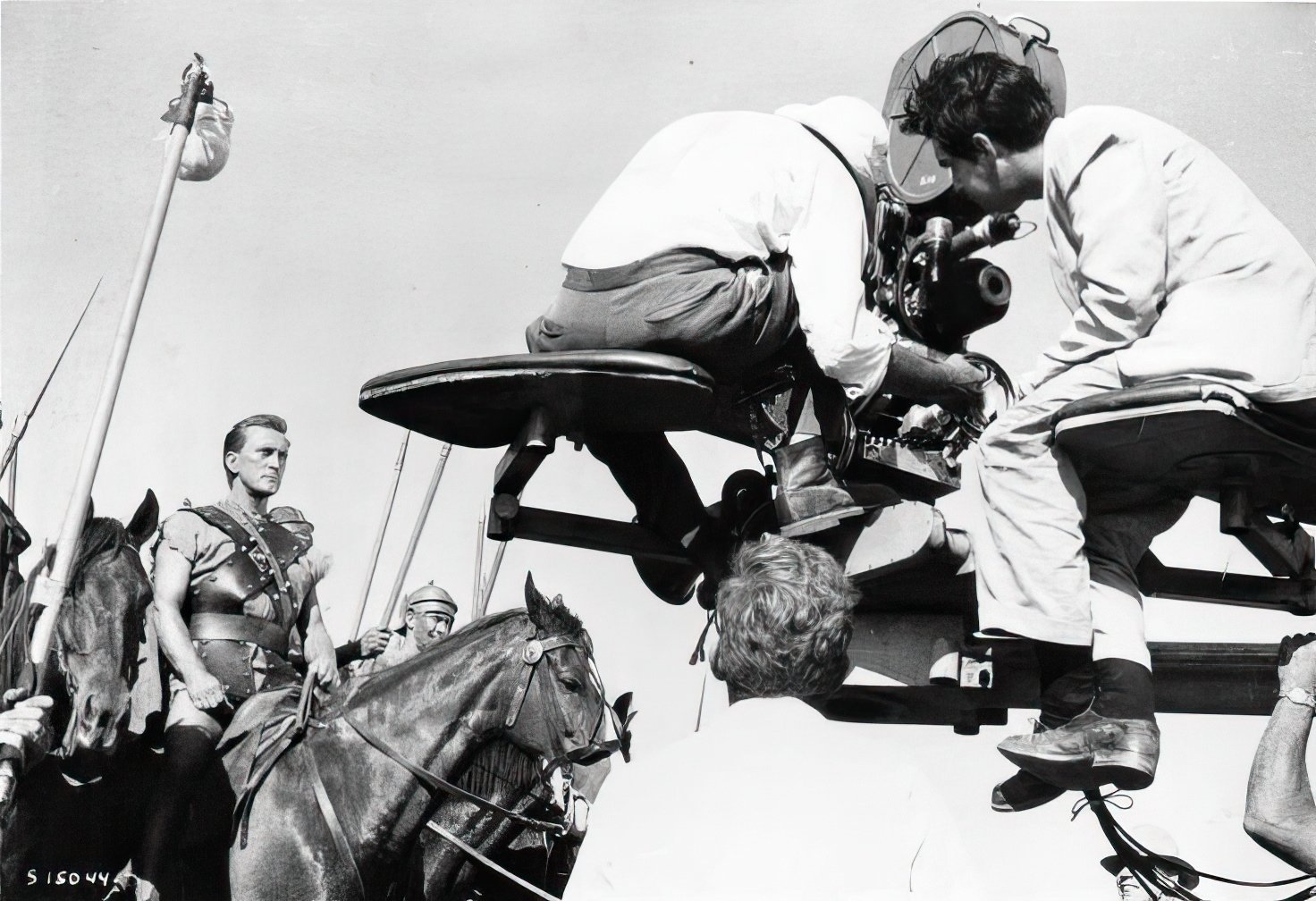

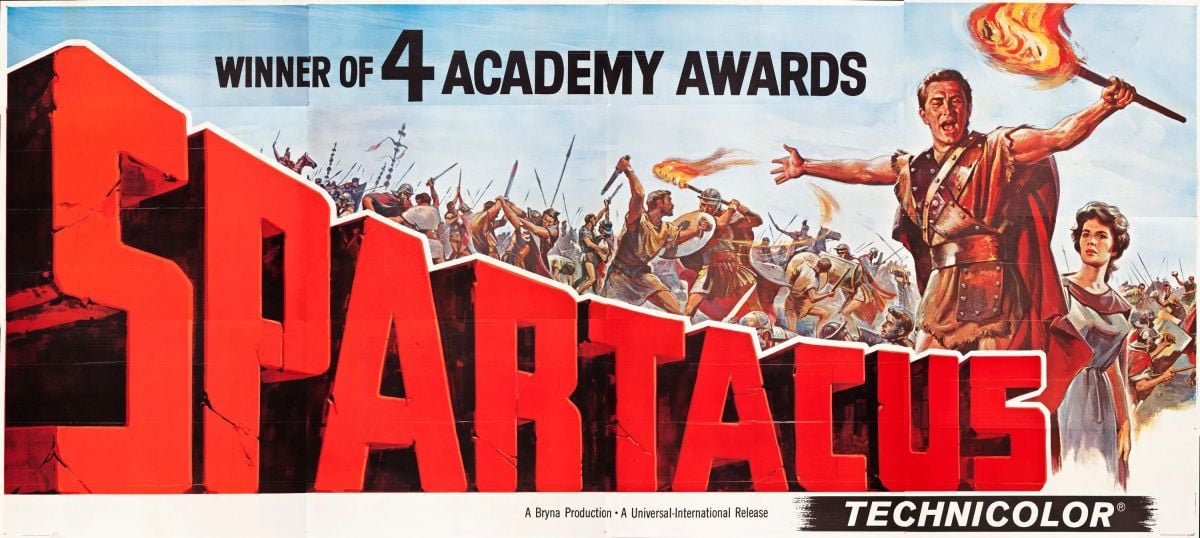

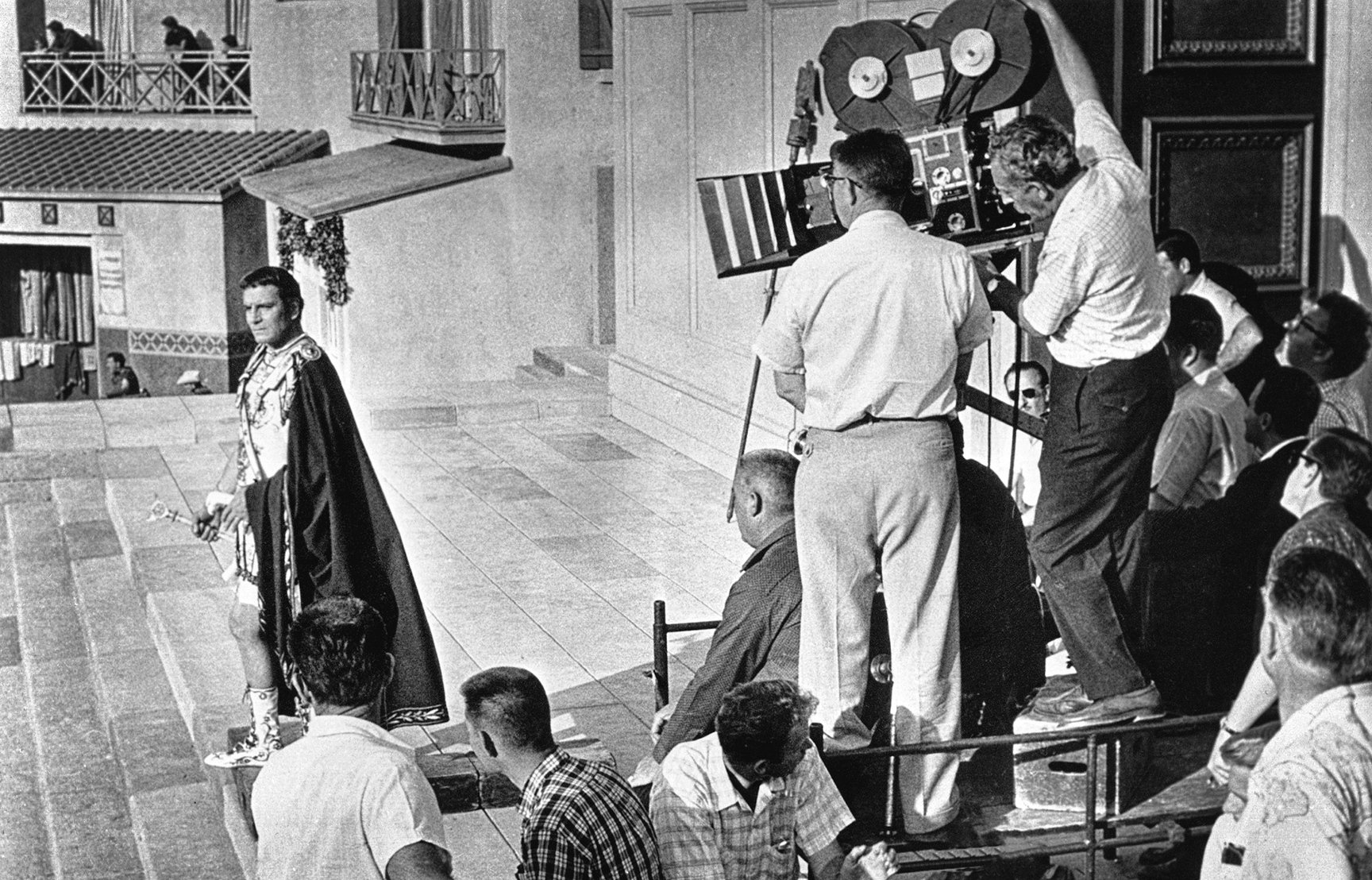

In an era composed of one gargantuan, breathtaking movie spectacle after another, Spartacus (1960), directed by Stanley Kubrick and produced by and starring Kirk Douglas, was one of the biggest. The most expensive film ever produced in Hollywood to that time, with a budget exceeding $12 million, Spartacus employed over 10,000 people and stayed in production 167 shooting days. Audiences who experienced the dazzling Super Technirama 70 images and brilliant six-track sound have never forgotten the film's impact.

Unfortunately, Spartacus has been little more than a memory ever since. Except for a 1967 reissue, in which the film — and the camera negative itself — was drastically re-edited and cut by a half-hour, Spartacus has been unseen except within the unfriendly confines of the television screen for the past thirty years. For a while, it looked as though the video would be the film's final resting place. The original negative, in addition to its missing footage, had faded irrevocably; no new prints could be struck.

Happily, thanks to MCA/Universal's desire to get its only real modern epic back into fighting shape, one more chance has emerged to witness the screen-filling, eye-popping spectacle of the kind that audiences of 1960 took for granted. Robert A. Harris, the man behind the 1988 restoration of Lawrence of Arabia (1962), has, along with James Katz, brought Spartacus back to life, creating a new negative from the black and white protection masters, rebuilding the intricate soundtrack, and reinserting scenes which were snipped by order of the censors in 1960. The restored Spartacus is receiving limited theatrical release this Spring [1991] and will later be released on videocassette and laserdisc.

"I think it's an important film," says Harris in his Mamaroneck, New York headquarters. "Spartacus is a large format film, the work of one of our great directors, and the acting is incredible. It's much more accessible than Lawrence of Arabia, a big, beautiful, sprawling epic of the kind that really can't be made anymore. Is it one of the two or three greatest films ever made? Absolutely not. But it's a damn good film and it's a film that needed to be restored, needed to be saved."

“The trouble with epics is usually the characters are flat; they aren’t three-dimensional, they aren’t real. We never let the size of Spartacus drown out the characters.”

— producer and star Kirk Douglas

The real Spartacus, a remarkable man about whom relatively little is known today, was a Roman slave who led an insurrection against his captors in the years 73-71 B.C. Spartacus and his followers, over 90,000 Celtic, German, and Italian slaves, routed five Roman armies before he was defeated and crucified by Marcus Licinius Crassus, a Roman politician and general.

Over the passing centuries, Spartacus became a legend. A symbol of the eternal fight against oppression, he inspired countless folk songs and stories. In 1831 playwright Robert M. Bird transformed these stories into a wildly popular stage spectacular called The Gladiator which ran for decades with Edwin Forrest in the title role. In 1914, a mammoth feature film called Spartacus or The Revolt of the Gladiators was produced in Italy with Amleto Novelli in the title role.

Spartacus emerged again in 1951 as the subject of a novel by blacklisted writer Howard Fast. Kirk Douglas read the book in 1957 and recognized its potential for himself and his company, Bryna Productions, Inc. In the late 1950s, widescreen epics were the rage in Hollywood, but Douglas saw something more in Spartacus. "My concept of Spartacus was to make it as if it were a little picture so that every character would become more dominant than the background," says Douglas. "The trouble with epics is usually the characters are flat; they aren't three-dimensional, they aren't real. We never let the size of Spartacus drown out the characters."

Fast wrote a screenplay based on his book, but Douglas found it lacking dramatically and brought Dalton Trumbo in to rewrite it. Trumbo, like Fast, had been a victim of the blacklist because of his refusal to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee. From 1949 on he wrote under a variety of pseudonyms. One of them, Robert Rich, won an Academy Award in 1956 for the screenplay for The Brave One.

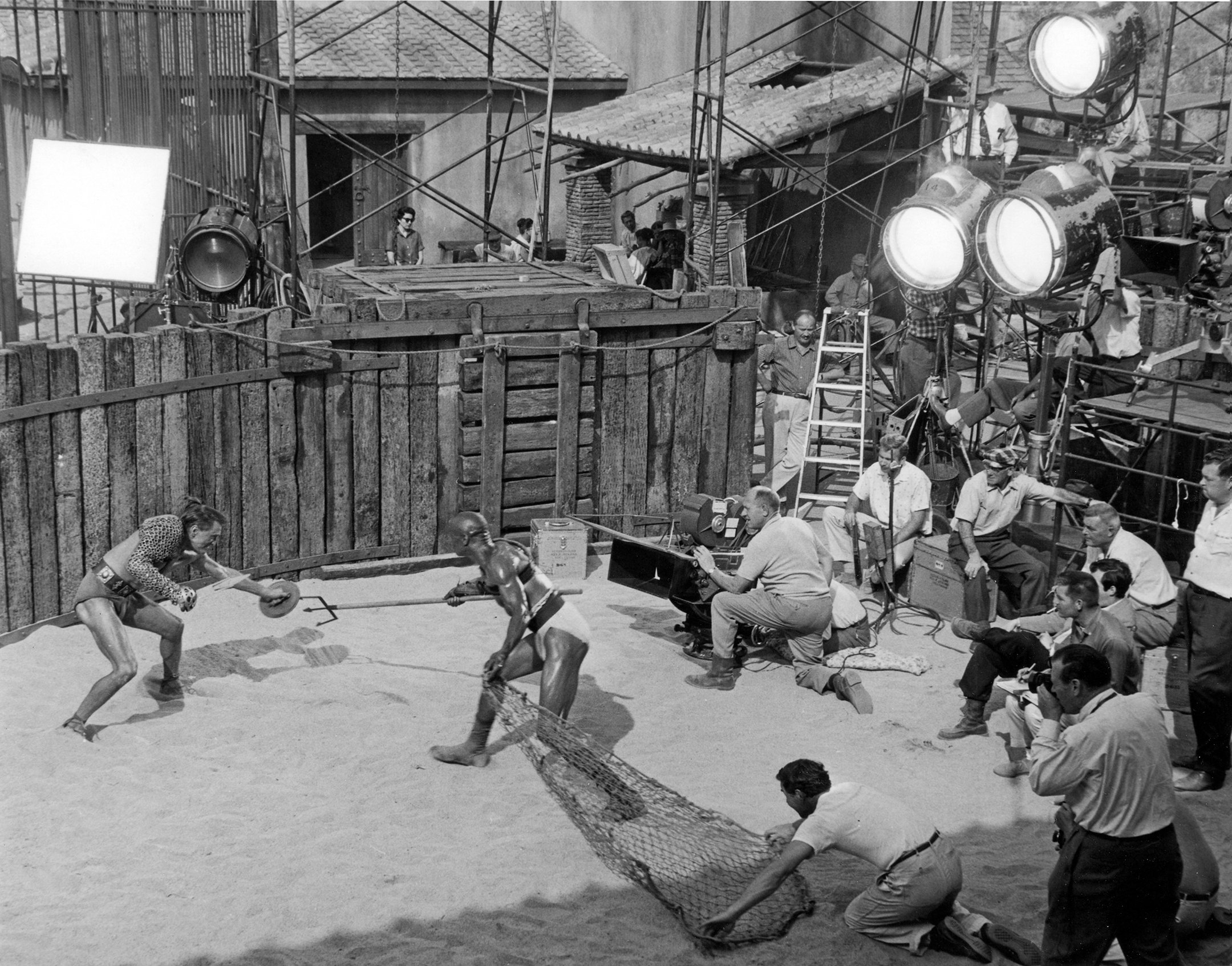

Douglas used Trumbo's script to attract a powerhouse cast, including Laurence Olivier, Peter Ustinov, Charles Laughton, Woody Strode, Tony Curtis, John Ireland, John Dali, John Gavin, Herbert Lorn, Charles McGraw, and virtually every stuntman in Hollywood. Sabina Bethmann, a German actress, was awarded the role of Spartacus' lover, Varinia.

After trying to interest David Lean in directing the film, Douglas reluctantly accepted studio pressure to hire Anthony Mann. "I never wanted Anthony Mann to be the director," says Douglas. "He was a nice guy and made a lot of successful movies but I didn't think he was right for Spartacus.”

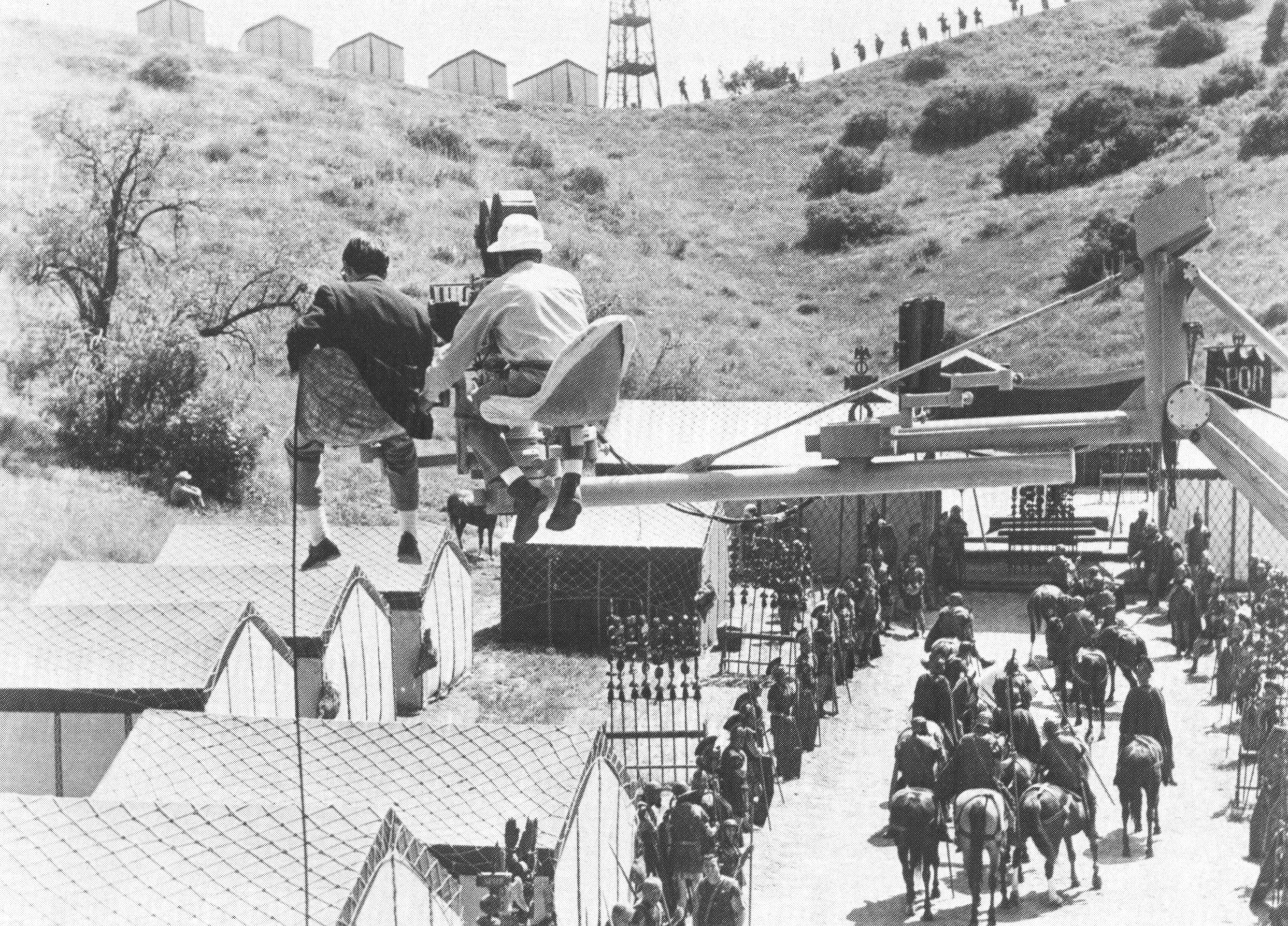

Douglas was easier to convince when it came to the cinematographer: Russell Metty, ASC. Behind the camera since 1935, Metty had provided magnificent images to films as diverse as William A. Wellman's The Story of G. I. Joe (1945) and Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil (1958). Perhaps Metty's finest and most representative work can be found in his intricate and powerful crane shots for Douglas Sirk's florid melodramas Magnificent Obsession (1954) and Written on the Wind (1956).

Spartacus was filmed in Super Technirama 70, a recent enhancement of Technirama, which had been around since 1957 and was itself an anamorphic variation on VistaVision. Super Technirama 70 release prints were on 65mm stock, but the negative utilized 35mm film on which the exposed image was printed horizontally, eight sprockets wide. The projected aspect ratio would measure 2.05x1. The enhanced clarity of the huge image was one advantage of Super Technirama 70; another was the spectacular six-track stereophonic sound.

Spartacus was only the third feature shot in the process, following King Vidor's Solomon and Sheba (1959) and Walt Disney's Sleeping Beauty (1959).

Unlike most location-happy epics of the period, Spartacus was filmed almost entirely on the Universal back lot. Virtually every standing set was refurbished or razed, including the Ma and Pa Kettle house, the Phantom Stage, site of the famous Paris Opera House, and the European street. The transformation took about six months of planning and another six months of construction, under the direction of art director Alex Golitzen. Locations in the San Fernando Valley and Thousand Oaks, with a few strategically placed backdrops to mask the freeway traffic in the distance, stood in for the Italian countryside. "You've got to rebuild Rome to shoot Roman history," Douglas said at the time. "Why cross a continent and an ocean to do that when the finest pool of technicians and talent in the world is in your own back yard?"

The Spartacus company only went beyond an easy drive from Universal for a few scenes: Laurence Olivier's lavish villa was actually Hearst's Castle at San Simeon; the climactic battle between Spartacus' slave army and the massed forces of Rome were shot on a plain near Madrid, Spain; and the opening scenes were filmed in Death Valley.

Production began on January 27, 1959. After two weeks, Universal told Douglas to drop Mann. "Then I fought!" says Douglas. "I don't like to change. Once you're married you try and make the marriage work." In his heart, however, Douglas believed that Mann should be removed. Friday, February 13, was Mann's unlucky day. Douglas fired him and paid him his full $75,000 fee. The quarry scenes which Mann shot still open the film. Ironically, Mann would go on to direct two of the biggest and best — and most intelligent — of epics: El Cid (1961) and The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964).

Mann was replaced by Stanley Kubrick, who had just left Marlon Brando's eccentric Western One Eyed Jacks (1961) in the directorial hands of Brando himself. Kubrick and Douglas' previous collaboration, Paths of Glory (1957), had been successful, although the two men did not always see eye to eye. "The kid has a healthy ego," said Douglas at the time. "He infuriates you at first, then you settle down and admire him."

“I didn’t always agree with him, but Kubrick did some brilliant things.”

Douglas calls Kubrick a “brilliant director. In my book I called him a shit, which I think he is. But he’s a very, very talented guy. I divorce one from the other. You don't have to be a nice guy to be a talented guy.”

If Spartacus is less a "Stanley Kubrick Film" than Paths of Glory or later masterworks like 2001: A Space Odyssey, it is because all the aspects of the production were set before he entered the scene. Peter Ustinov says of Kubrick, "One knew there was considerable talent there, and perhaps more than that, but he wasn't allowed to display the creative qualities on a big scale that he showed with much smaller films like The Killing (1955). He was still an employed man." Kubrick did, however, leave his mark on Spartacus. His first action was to discharge actress Sabina Bethmann, saying she "lacked experience." He offered the role of Varinia to Jean Simmons, who readily accepted. "Making a film with Kubrick was very exciting," Simmons says. "This kind of Biblical thing didn't seem to be quite his cup of tea, but I think it turned out to be one of the best films of its kind."

Kubrick's major contribution to the Spartacus script was in pruning away some of Dalton Trumbo's excess verbiage, changing it to, he said, "a more visual conception, and removing all but two lines of Kirk Douglas' dialogue during the first half hour of the film's three-hour-plus run time. We fought about that one, but I won."

"I didn't always agree with him," says Douglas, "but Kubrick did some brilliant things. He's the one who conceived the whole idea of the love relationship between Jean Simmons and me. He took out all the dialogue, when she goes around feeding everybody, and the camera keeps coming closer and closer. That was all Stanley."

Kubrick seemed unfazed by the logistics of this mammoth feature, and by the size and shape of the Technirama picture: "I must confess that I never thought very much about the proportions of the wide screen after the first day or two. I think that too much emphasis is put on it. It is really just another shape to compose to."

Although planned carefully, the production was plagued with mishaps. Jean Simmons dropped out of filming for over a month when she needed emergency surgery. Tony Curtis split his Achilles tendon while playing tennis and was placed in a hip-high cast for a month. No sooner did he return to the set than Douglas was downed with a virus and bedridden for 10 days. Spartacus was soon months over schedule and had seen its budget doubled. Peter Ustinov says, "It went on for an awfully long time. My daughter was born right before the beginning of it, and by the time the film was still doing retakes she was old enough, in kindergarten, that when asked what her father did with his life, she answered, 'Spartacus.' I did the final retake four days before the film opened."

After production was completed in California, Kubrick, Douglas, and the crew flew to Spain to begin plotting and filming the huge battle-scene climax. Eight thousand infantrymen from the Spanish Army were recruited to play the Roman legions. They learned to form hollow squares of 10 cohorts of 360 men each, not including officers and standard bearers. Kubrick and Metty filmed the sweep of action from three 110-foot towers.

Between shots, Kubrick assigned each "dead" man in the field a piece of cardboard with a number, making it possible for him to compose his scene more quickly by shouting, "Number 16, a little further to the left!" The battle and aftermath scenes, which take only a few impressive minutes onscreen, took six weeks to rehearse and six weeks to film.

The violence in Spartacus represented the early stages of the more explicit mayhem of the 1960s. Douglas says, "In the battle, I had two men: one had only one leg, one had only one arm. We manufactured an arm and a leg for them and in the battle I slashed off one arm — we had it arranged with blood vessels and everything — and slashed off the leg. That scene scared the hell out of me ’cause I had to be very careful — I didn't want to slash into the stump!"

Back in Hollywood editor Robert Lawrence soon was doing cutting of another sort. While Alex North composed a powerful musical score, Lawrence worked the footage into 197 minutes of pageantry, violence, and drama. This version was shown to a few critics who received it favorably, but the censors were not so impressed. They ordered the excision of several scenes of carnage in the battle — including Douglas' limb chops — as well as a scene in which Olivier attempts to seduce his servant played by Tony Curtis. The total cuts amounted to some five minutes.

Those who had seen those few minutes, however, missed them when they were gone. Columnist Archer Winston wrote in the New York Post:

"Such cuts... tend to reduce a work of character to a least common denominator. When this is done without public notification a few objectors are served at the expense of a majority who are not getting genuine product as made, praised, and originally presented. If this were done with a packaged, labelled drug the company could be prosecuted."

Nevertheless, Spartacus was enormously successful at the box office upon its release on October 7, 1960. Within a year the film had grossed over $13 million, out-grossing even the popular West Side Story (1961). Spartacus won Academy Awards for best supporting actor (Peter Ustinov), color cinematography, art direction, and color costume design, and received nominations for editing and musical score. Spartacus also won a Golden Globe as best picture and was named as one of Time magazine’s 10 best films of the year.

When Universal re-released the film in 1967 (in 35mm prints only), numerous more cuts were made and the film was substantially reedited; that version ran at 161 minutes. It looked as though Spartacus would never again be seen in its original form.

Over 20 years later, the successful restoration of Lawrence of Arabia under his belt, film archivist Robert A. Harris began to wonder if Spartacus could be similarly brought back to life. He approached Universal and found that MCA Motion Picture Group chairman Thomas Pollack had been thinking along the same lines.

"There are a few films that I remember from my teens that really showed me the power of film," says Harris. "And when I feel one of these films is disappearing I have to do something about it."

Harris, working with James Katz, found that the original negative had deteriorated beyond repair. He says, "Universal took very good care of it, but it was 30 years old. The yellow layer was gone; we made some tests off the camera negative and ended up with blue shadows and yellow facial highlights."

The black-and-white protection masters did exist in good shape, however, and gave Harris and Katz a basis toward rebuilding Spartacus step by step. "However, the protection masters are in Technirama," says Katz, "which means they're on 35mm film, horizontal formatting, eight perfs wide with a 150-percent squeeze. And there's no equipment around that will conveniently convert it to 65mm. We've been trying to come up with a process which will give us a sharp image across the screen and keep it in registration, and that's been a major problem."

Some of the scenes existed as picture only and a few minutes of sound had to be re-recorded. Tony Curtis re-recorded about a minute of dialogue in Los Angeles and Anthony Hopkins stood in for Laurence Olivier for some looping done in London.

Harris says, "If it were up to me, I'd restore it back to the last preview because there were some excellent scenes. But that material was destroyed in the mid-Seventies. We're going back as close as possible to the pre-censorship version, the last approved version from Kubrick and Douglas: 197 minutes. The picture will be slightly grainier than in 1960 because we're two generations farther away, but the original material, since it was Super Technirama, was so sharp to begin with that it's going to be gorgeous."

The reissue of Spartacus, coming hard on the heels of Kirk Douglas' Life Achievement Award from the American Film Institute, will be a cinematic event of great importance, especially in these days of tiny movies shown on tinier screens. "There aren't many more out there like this," says Harris. "Not of this size and of this intelligence."

Kirk Douglas says, "It's great to see this thing done in the way it was meant to be done. Sometimes a film you loved years ago doesn't hold up when you see it again. But Spartacus is really something special."

Peter Ustinov, on the other hand, remains a bit more blasé about the prospect of seeing himself, 30 years younger and magnified to epic proportions. "I'm going to have the same reaction as Dorian Gray. One of absolute horror." He laughs. "I shall recoil from the screen."

In 2017, Spartacus was one of 25 films selected to be added to the National Film Registry in the Library of Congress as a motion picture that is “culturally, historically or aesthetically” significant.

The film was digitally remastered by NBC Universal in 2020 with a new 4K version created to celebrate the film's 60th anniversary:

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.