Homeward Bound With Star Wars: Skeleton Crew

ASC members Sean Porter and David Klein forge a strong alliance to launch the sci-fi adventure.

This story originally appeared in AC March 2025.

Speaking about Star Wars in 1977, George Lucas told Time, “It’s aimed at kids — the kid in everybody.” The latest entry in the franchise, Skeleton Crew, not only continues this tradition, but is actually about kids.

The Disney Plus series, shot by ASC members Sean Porter and David Klein, begins on the secluded forest planet of At Attin, as four youths — three human and one alien — venture into the woods in search of an ancient Jedi temple. The structure turns out to be a spaceship, and the kids inadvertently launch themselves on a perilous adventure.

Porter notes that “around 35 to 40 percent of the series was shot in the volume, and the rest was either stage, bluescreen or backlot — and we did a lot on the backlot.”

Klein adds, “The LED volume was really powerful with The Mandalorian, because the main subject was a highly reflective character, and you see all the sources — but on Skeleton Crew, there was a priority on faces, so it didn’t matter what we did on the ceiling so much. One of the first things we did was take all the removable ceiling panels from Stage 20 and use them to build additional walls to surround the kids’ ship.”

The show was created by Jon Watts and Christopher Ford (Spider-Man: No Way Home). Porter shot Episodes 1, 2, 7 and 8, and Klein Episodes 3-6 — with 2nd-unit photography on all eight episodes by Paul Hughen, ASC. Series directors comprised David Lowery (Episodes 2 and 3), Daniel Kwan and Daniel Scheinert (aka “The Daniels,” Episode 4), Jake Schreier (Episode 5), Bryce Dallas Howard (Episode 6) and Lee Isaac Chung (Episode 7). Watts directed Episodes 1 and 8.

The season was produced under the watchful eyes of such Star Wars stalwarts as Jon Favreau, Dave Filoni, Kathleen Kennedy and Colin Wilson.

“These shows are so massive that you can’t do them alone. We fail together or we succeed together — that’s how I see it.”

— David Klein, ASC

“Death and Rebirth”

“This show was a huge challenge to me,” says Porter, whose credits include the features Green Book and 20th Century Women, and the series The Old Man. “It’s such a big show, and it was my first time co-DP’ing, which was really hard for me. I had to have a kind of death and rebirth.

“I come from features and want authorship over my images, I want to see something through from start to finish, I want to understand all the arcs — I want to be in control of all the arcs. You immediately think of all the things that could go wrong. If we have shared responsibilities, who’s accountable? But this job required a collaboration that I’ve never experienced.”

For his part, Klein was familiar with what a Star Wars series would require, having joined the franchise on Season 2 of The Mandalorian (AC Feb. ’20) and moving on to shoot multiple episodes of The Book of Boba Fett (AC Dec. ’22) and Mandalorian’s Season 3.

Klein recalls with a laugh, “With Porter, really, it was like, ‘Hey, get on the bus!’ On shows of this size, you kind of have to let go, because there are so many special effects, visual effects, makeup effects, everything. These shows are so massive that you can’t do them alone. We fail together or we succeed together — that’s how I see it.

“There were three of us — Porter, me and [2nd-unit cinematographer] Paul Hughen [ASC],” Klein continues, “and on any given day throughout the entire process, one of us was prepping. And that’s the only way it would work. You’re constantly trying to stay ahead of stage builds, rigging and lighting the stages, and also building the content for the volume. It took three of us, no doubt. And we’ve got to tip our hat to VFX supervisor John Knoll because at the end of the day, he made us all look good by blending everything together. He and his team always do spectacular work.

Despite his initial misgivings, Porter very quickly came to see the benefits of the collaboration once prep commenced. “I felt like I got an ally so quickly in David. The more we had to struggle together through this process to figure out how we were going to do it, the more I realized just what a true friend and ally he was. I think before this job, a different version of me would have walked away from this show, but I’m so glad I didn’t. I climbed on the bus with a supporter, friend and mentor. I want to make this point because I think many other DPs go through the same kind of [doubts] on these massive projects. You just gotta get on the bus. It’s worth it!”

Single-Camera Strategy

Production on Skeleton Crew took place at MBS Media Campus in Manhattan Beach, California, and incorporated traditional sets, a healthy dose of bluescreen, and Industrial Light & Magic’s StageCraft LED-wall-volume technology, as well as a substantial backlot area at California State University, Dominguez Hills. Though television productions commonly deploy multiple cameras, especially with young actors, the Skeleton Crew team took a single-camera approach — primarily with the Arri Alexa Mini LF and occasional use of the full-size LF. “We did some multi-cam when it was really necessary,” Porter says, “but in the ship [the Onyx Cinder], in those tight spaces and on the volume, when we’re trying to work with overlapping frustums, the requirements back you into the decision to use one camera. It’s a big part of the cinematographer’s job to see the limitations and then have a design that complements those limitations rather than fight them. There’s an art to that.”

From an aesthetic standpoint, he adds, “I guess you could call it a more nostalgic version of filmmaking, but there’s something about single camera — it’s about focus. Everybody tends to pay a little more attention. I’m not saying that you can’t get great material with multiple cameras, but there is a slight shift in the energy of the room, and Jon Watts was very perceptive of that.”

Klein likens single-camera work to “being the quietest person in the room, and everybody leans in to listen to what you’re saying. It focuses the energy all in that one place. When we did shoot multiple cameras, it was usually side-by-side, a medium and a close-up or something like that, which, for my money, is pretty much the same thing as single-cam.”

Workspace Challenges

Klein notes that achieving more classical lighting in the volume can be “tricky — these stages were never really designed for that. If cinematographers were designing a volume stage, we’d have 60 feet around it — behind it — so we could set up fixtures correctly. You can’t just have an 18K — you’ve got to have some distance to that source, so trying to create those kinds of looks was a big project in and of itself. In these stages, we have these tiny, little walkways, gangplanks and tiny mezzanines that are really just there for volume control — formerly known as the “brain bar” — to do their work, or for Fuse [Technical Group] to remove or replace panels. We’re trying to do in that space what we normally do on set.”

Porter recalls an eye-opening moment when key rigging grip Jason Selsor first showed him around: “It’s easy to stand in the middle of the volume and point and say, ‘I want a big thing to come from here and I want this kind of fall-off …,’ but Jason took us on a little tour and showed us what we were really dealing with. It’s a mess up there above the LED volume! It’s all pipe and wood, and getting anything up there is a small miracle.

Making Discoveries

The cinematographers fine-tuned their approach as the shoot progressed, making discoveries along the way. “Toward the end of the show, we ended up combining volume control with lighting control so our dimmer-board operator could make simple light cards on the LED walls and cue them with our other lighting through the board,” Porter enthuses. “So, basically, we had DMX control on the wall and for our off-wall fixtures. We’d use that for blaster fire or other bits like that. It was really nice to be able to have that control completely with the lighting team.”

Additionally, Klein reports that the team figured out how to significantly improve virtual depth-of-field control on the wall. “It was driven by focus puller Ryan Mhor’s Preston [wireless focus control],” he says, “and it defocused the virtual content according to its virtual distance, so an object that was ostensibly near the physical wall went out of focus slower than an object that was deep in the virtual world. The early development of this was started by 1st AC Dominik Mainl during Season 3 of The Mandalorian and on Ahsoka (AC July ’24).

“Unfortunately, the physics are a bit inaccurate, and we couldn’t just set it to the same stop as our production lens,” Klein continues. “Because the production lens would do [only] half of the work, the inaccuracies of the VDoF became apparent and just looked like a blur. So, if we were shooting at a T2½, we often wouldn’t set the wall to a virtual T2½; instead, we’d set the wall to a T4 or T5.6, and that would look better.

“After doing some tests, we also realized that not everything in the virtual world should defocus the same. With the tunability that volume control worked into the function, we could assign the virtual depth-of-field to limit highlights above a certain range to not defocus. We could also assign the low end to not defocus below a certain density so that the virtual depth would only alter the middle range and let the lens do the rest. That felt a lot more real.

“There’s an amazing synergy with the ILM and StageCraft teams,” Klein adds. “They take the weirdest requests and come back a day later and say, ‘Okay, now you can do that!’ They’re our ‘Space Wizards’ — a term that executive producer Dave Filoni came up with for the volume control.

Kid Energy

Porter notes that the enthusiasm exhibited by Skeleton Crew’s four young stars — Ryan Kiera Armstrong, Kyriana Kratter, Ravi Cabot-Conyers and Robert Timothy Smith — enhanced the production experience. “They were such a joy to have on set, and they were so excited to be there. These kids just showed up ready to work. There was a lot of levity, and I think everybody enjoyed the work a little bit more just having them around.”

“We needed that kid energy to keep us afloat,” Klein concurs with a laugh. “And something special was born out of that: an energy that translated into the visuals.

Tech Specs:

2.39:1

Cameras | Arri Alexa Mini LF, Alexa LF

Lenses | Arri/Zeiss Master Anamorphic, Canon CN-E Compact Zoom (VFX)

Spotlight on Lighting | Overcoming Limitations

In Episode 4, Klein was tasked with a challenge to produce pronounced sunlight while keeping production in the volume. He explains, “Full sunlight, or full moonlight, for that matter, pushes us off of the volume and onto the backlot — because if you push too much direct light into the volume, it bounces all over the place and washes out the screens, making them pretty much useless. But we learned early on with the volume work that broken-up sunlight looks great. The problem was, though, that we couldn’t just put up HMI or tungsten fixtures for direct hard light because there was no space. So, I used 18K HMIs from the floor, behind the volume wall, and aimed them into mirrors above the wall, about 20 feet up — and that roughly doubled the distance the light traveled and gave us really sharp shafts that worked beautifully with all the atmosphere we put in there.”

Porter faced a similar challenge on Episode 8, in this case shooting on a bluescreen stage, but with similar space restrictions. In this nighttime sequence, the kids have returned to At Attin as the planet is attacked by pirates. They venture into their school, and beams of moonlight stream into the structure. “It’s night, and we’re dealing with the limitations of space,” Porter says. “How do I get beams of light that behave like parallel beams [from an infinite distance] shafting through holes in this ceiling when we have such limited height to work with?”

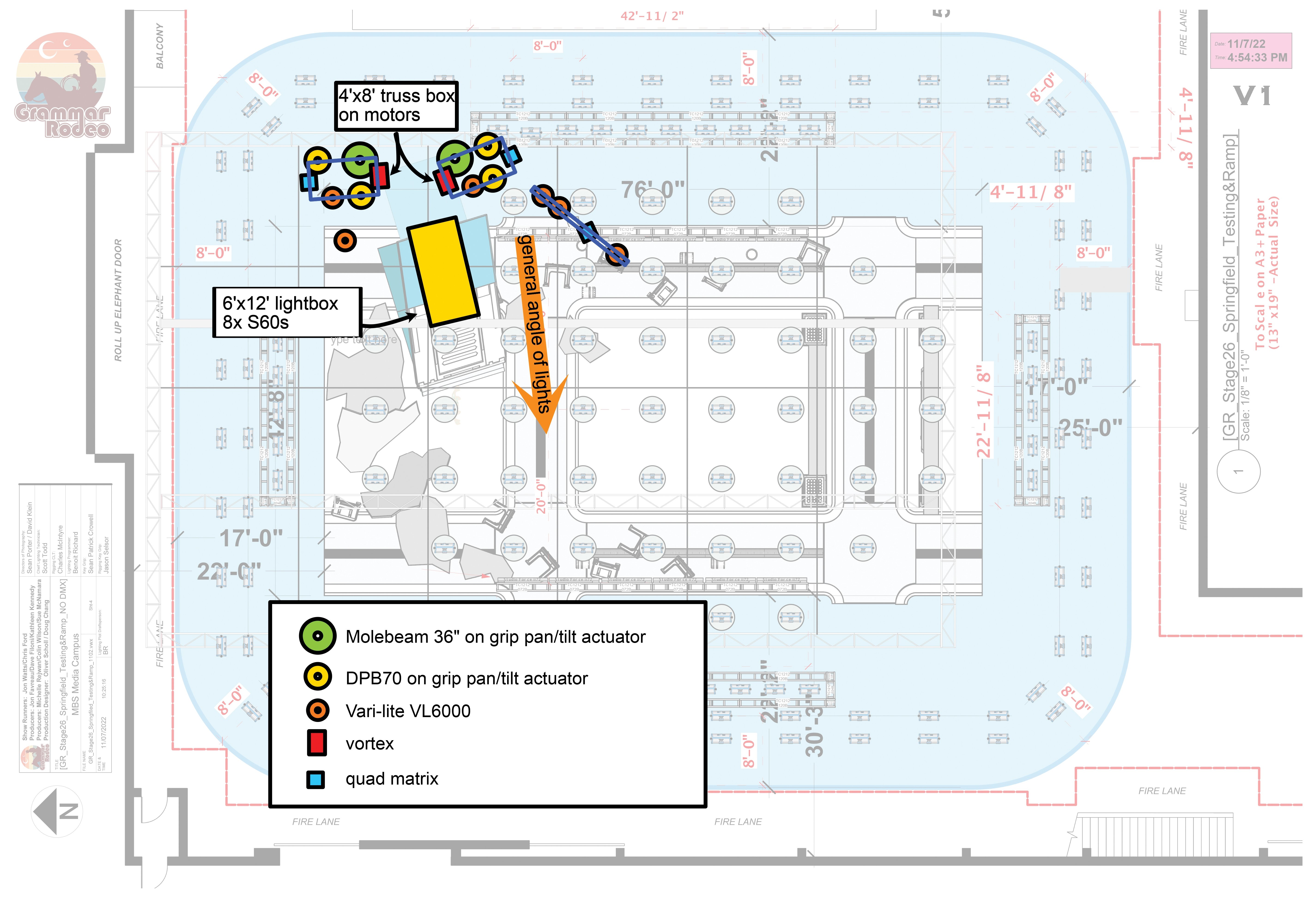

The space limitations warranted a combination of 36" Molebeams, Dedolight DPB70s and Vari-Lite VL6000 motion fixtures, with Creamsource Vortex8s and Fiilex Quads mixed in — all rigged above the set wall. “We needed a number of them to provide individual shafts through all these little holes — little slivers and shards,” Porter recalls. “I originally thought that if all the fixtures in the array were truly parallel and pointed in the same direction, then it would work, but we quickly found out that only worked from one camera position; as the camera moved, the beams would parallax and not look like they were all coming from the same source. So, we had to have them all more or less operable so that as the camera moved, we continually tweaked the beam angles. [To do this, the fixtures] were ganged together on two motor-driven trusses and then the beams had their own independent control [with] pan/tilt actuators.”

One bit of newer tech the cinematographers employed was dynamic diffusion. “It’s a translucent material we controlled by DMX, so you can vary the opacity via a dimmer board,” Porter explains. “I collaborated with an architectural supplier of smart-window film and developed the four frames myself. During production, we tapped Legacy [Effects] to help us build a prototype DMX controller for the panels, so we could run them to the board,” enabling them to be controlled/animated by the board operator.

“With a few pieces of dynamic diffusion across several fixtures, we could get a really realistic moving-cloud effect, where the sky starts clear and then the clouds roll in,” Porter adds. “Because it was still very early in the development of this tech, there was a bit of a color cast to it, but that’ll get better.”

Spotlight on Optics | Sharp Edges and Signature Flares

Anamorphic Without Compromise

The visual language of the Star Wars world is rooted in the anamorphic format, and after testing a variety of anamorphic optics, the Skeleton Crew team chose Arri/Zeiss Master Anamorphics. Porter explains, “Jon Watts and I used them on The Old Man, where Jon wanted a set of anamorphics that he felt didn’t compromise [the image] when shooting wide open or [including important information] at the edges of the frame — he wanted edge-to-edge and top-to-bottom sharpness. And on [Skeleton Crew], he wanted to be able to put little Easter eggs all over the frame and compose three-shots and group shots without smushing an actor into oblivion. We wanted to bring some of that aesthetic into this new world, which is pretty much the opposite of what most DPs do on the volume; they err on the side of mucking the image up because that’s when you’re drawing the least attention to the gag and it can be most effective.

“That’s one of those examples where DK [Klein] was so generous and patient,” Porter adds. “I was like, ‘These are the lenses I want to use,’ and he didn’t say, ‘That’s never going to work.’ He said, ‘Let’s try it out.’”

After seeing extensive moiré in the volume with the Master Anamorphics in testing, the cinematographers found they could mitigate it by putting one of the Arri/Zeiss flare attachments on the rear element of the lens. “Then, it suddenly behaved [with the wall] a lot more like the [Panavision] Ultra Vistas and [Caldwell] Chameleons [used on The Mandalorian] did — a lot more forgiving,” Klein says.

With that, “we found we could have our cake and eat it, too,” says Porter. “We got the edge-to-edge sharpness with a more forgiving lens on the LED wall. We weren’t throwing away half the frame to anamorphic softness.”

Hair in the Gate

The cinematographers found a far less conventional solution for another concern. Klein notes, “One limitation I didn’t like with the [Master Anamorphics] was that they don’t flare much at all [even with the additional flare element]. One of the tricks we learned in music videos and commercials back in the day was to put a piece of blue monofilament on the back of a spherical lens to create a faux anamorphic streak flare. We tried that here, but the monofilament was too clinical and clean. We tried all sorts of other materials, including copper and steel wire, and even scuffed them up a bit, but they were still too clinical. So, Sean had the idea of putting a human hair behind the lens. The result was subtle and organic, and just what we were looking for!”

Adds Porter, “What was even crazier was that each person’s hair had a unique signature to it. Everybody’s hair produced a different kind of flare than a hair from another’s — so we needed hairs from everybody on the crew.”

Klein, who sports a bald dome, offers wryly, “Well, not everyone…”

After a laugh, Porter notes, “It was amazing to see how wildly different each person’s hair was — it was kind of like a digital fingerprint. I even tried hair from my son, Jackie, and it created this insane rainbow-like look. In the end, we used some dark-brown hair we culled from a slew of different sources. It had to be delicately and carefully applied because if it’s not laser-straight, then the flare gets all wonky.”

“It was just one strand secured to the back of each lens with a little dab of nail polish. Basically, we solved the flare problem by putting a hair in the gate!”