Ahsoka: Framing a Rebel Saga

Eric Steelberg, ASC and Quyen Tran, ASC collaborate on an intergalactic Star Wars adventure.

Images courtesy of Lucasfilm LTD

The pair of cinematographers shooting Ahsoka were presented with a trove of creative challenges, which called for quick acclimation to new technologies, innovative solutions, detailed research and an uncommon degree of cooperation between two directors of photography. The production of the Disney Plus series saw its fair share of work on the Lucasfilm/ILM StageCraft OSVP stage — or volume, as it’s often referred to — as well as in more-traditional shooting environments, and within all these filming scenarios, the mission for ASC members Eric Steelberg and Quyen Tran was to produce imagery of a piece with the Star Wars universe.

Acclimating to the Tech

The Lucasfilm approach to virtual production involves live-action photography against high-resolution LED backdrops displaying environments rendered in real time with the Unreal Engine platform. ILM’s proprietary StageCraft software combines 3D camera-positioning data with the output from Unreal to create a virtual field of view (the “frustum”) with proper 3D parallax on the LED wall of the OSVP stage. (For a deep dive into Lucasfilm’s ICVFX techniques, see AC technical editor Jay Holben’s detailed article in the magazine’s Feb. 2020 issue, which explores the work of ASC members Greig Fraser and Baz Idoine on The Mandalorian, Disney Plus’ inaugural Star Wars series.)

Steelberg and Tran agree that virtual production is like having another brush to paint with. “The learning curve was probably more intimidating than it was steep,” says Steelberg, whose recent credits include Marvel’s Hawkeye series and the feature Ghostbusters: Afterlife (AC Dec. ’21). “I understood the concepts of virtual production, but I hadn’t actually worked in that environment. That’s where the rubber meets the road — you can think you understand something, but until you’re actually doing it, you don’t know anything.”

“Dave Filoni and Jon Favreau wanted to see us succeed, and we had a lot of the crew from The Mandalorian and The Book of Boba Fett on our team.”

— Eric Steelberg, ASC

Says Tran, “I’m pretty nerdy when it comes to keeping current on all the new digital cameras and new ways of filming. Prior to Ahsoka, my only experience with LED walls was doing process shots on a stage for the show Unbelievable (AC Oct./Nov. ’20), and that really piqued my interest in working with LED backgrounds on a larger scale.

Prepping for OSVP

Created by Dave Filoni, Ahsoka follows the title character (played by Rosario Dawson), the former pupil of Anakin Skywalker (Hayden Christensen), as she races across the known galaxy — and beyond — to prevent the ruthless Grand Admiral Thrawn (Lars Mikkelsen) from reigniting interstellar war. The story is set between the events depicted in Return of the Jedi and The Force Awakens, and is essentially the continuation of the narrative that ended with the fourth and final season of the animated series Star Wars Rebels, co-created by Filoni.

Ahsoka’s adventures take her to the ancient ruins of Arcana, the plains of Lothal, the shipyards of Corellia, the dark forests of Seatos and the plains of Peridea, all of which were filmed in and around Los Angeles — onstage and on a backlot.

The Season 1 directors were Filoni, Steph Green, Peter Ramsey, Jennifer Getzinger, Geeta Vasant Patel and Rick Famuyiwa.

“I’ve been a Star Wars fan for a long time, so I knew that at some point I was going to have to do a Star Wars show.”

— Quyen Tran, ASC

Preproduction began well in advance of filming, and Steelberg and Tran shared an office above the stages where David Klein, ASC and Dean Cundey, ASC were shooting The Mandalorian’s third season. They often dropped downstairs to observe the set.

“Dave Filoni and [executive producer] Jon Favreau wanted to see us succeed,” notes Steelberg, “and we had a lot of the crew from The Mandalorian and The Book of Boba Fett on our team, like gaffer Jeff Webster and key grip Walter ‘Bud’ Scott. So, from the very beginning, Quyen and I were part of a well-oiled machine.” Says Tran, “And we really leaned on their experience.”

Tran notes that she “ended up operating here and there on Season 3, as well as [providing] additional photography for Bryce Dallas Howard’s episode.” Steelberg adds that he had shot 2nd unit for Klein on Episode 4 of The Mandalorian Season 2, “and my work on that was what got me considered for Ahsoka.”

Sets displayed on the OSVP stage were built in Autodesk Maya for loading into Unreal during production, and the directors and creative team were available to scout virtually, Steelberg notes. He adds that “preproduction started during Covid, so I did a lot of scouts at home in virtual reality with a VR headset, where I could see our set on the [LED] wall and figure out where to place the lights and cameras, or how close we could get to the screens. Whenever I needed advice, Dave Klein was kind enough to jump in with me to do a remote scout and make suggestions.” Steelberg and Tran had complete control over lighting within their virtual environs, including real-time changes incorporated on set by the “Brain Bar,” a bank of computer workstations where a team of visual-effects artists make the technology of the OSVP stage function.

The LED walls themselves are also a great lighting tool, says Steelberg. “What the camera sees is actually a very small percentage of the whole [LED wall], the rest of which is rendered at a very low resolution, so you can black out that surrounding area like negative fill, or put up big white or gray shapes like virtual bounce cards.”

Adds Tran, “We could create ‘cards’ to be any shape or size and changeable at a moment’s notice — from density to intensity — which proved to be incredibly beneficial. But just as important when lighting within a volume was [keeping] the ‘flashing’ [i.e., the reflection of movie lights] off the screens [that were in frame]. Bud and Jeff were always on top of that as well.”

Choosing Glass

The Ahsoka cinematographers selected Caldwell Chameleon SC anamorphics as their primary lenses, paired with Arri Alexa LF cameras. This choice was initially prompted by Klein and Cundey’s use of the glass on Season 3 of The Mandalorian. After much testing, says Steelberg, he and Tran found the Chameleons to be “sharp, and they have really nice contrast with very little distortion. Our visual-effects team liked them especially for those reasons.”

The Chameleons are particularly well suited to shooting ICVFX, Steelberg adds, because “their [focus plane] falls off quickly, which allows us to get close to the LED screens. On a volume 60 feet in diameter, your actual footprint is more like 40 feet because you need to keep everything that you want in focus 8 to 10 feet away from the screen. Any closer and the wall starts to come into focus, causing the pixels of the screen to moiré against the [photosites] of the chip.”

Cooke Anamorphic /i FFs, which were also used by Klein and Cundey on their Star Wars project, were pressed into service as well, for focal lengths above 100mm.

The ability to automatically track lens settings through StageCraft is still under development, so the cinematographers relayed their focal length to the Brain Bar artists, who would adjust the size of the frustum accordingly. “In terms of adjusting focus of the virtual environment within the frustum, we would just eyeball it, because objects in the background were so far away, it was enough that the screen itself was out of focus,” says Steelberg.

Battles and Blades

Tran and Steelberg were both very excited by the prospect of working on a Star Wars property. For Tran, whose son was born on May 4 — of “May the Fourth Be With You” fame — it was a dream come true. “I’ve been a Star Wars fan for a long time, so I knew that at some point I was going to have to do a Star Wars show,” she quips.

Says Steelberg, “There was so much that was new to me that any time I accomplished something, it felt like a significant achievement. It was a lot of stress, but also a lot of fun.”

Steelberg’s first day of filming involved a scene from Episode 2, in which Ahsoka and New Republic General Hera Syndulla (Mary Elizabeth Winstead) enter a control room overlooking the Corellian shipyards and engage with Imperial sympathizers before Ahsoka breaks a window with her signature pair of lightsabers and leaps through it.

“For exteriors outside windows to look convincing, whether it be an LED wall or real location, I have always felt they need to be about two stops overexposed, so that’s approximately where I put the wall.”

“That was a daytime-interior set on the [OSVP stage], with the [LED] wall just outside the windows,” he explains. “I wanted to balance the set exposure with the screen outside to make it feel more natural, and it went off really well. For exteriors outside windows to look convincing, whether it be an LED wall or real location, I have always felt they need to be about two stops overexposed, so that’s approximately where I put the wall, using a spotter and my eyes/monitor.”

Lightsaber battles occur in almost every episode of Ahsoka, and they required a blend of practical and digital effects. On set, each saber blade was crafted from an LED strip loaded into an acrylic tube. While the blade would be substantially enhanced with VFX, the illumination from this rigging was essential in creating the interactive light of saber battles. The saber props were battery-powered and strong enough to spar with, while their color and intensity were wirelessly controlled.

Says gaffer Webster, “At 144 RGBW pixels per meter and with each lightsaber being roughly 1 meter, we had to find a way to avoid transmitting one universe of CRMX for each saber like we had done in the past, as RF congestion was always an issue on our sets. So, rather than patching each individually addressed pixel in the console and programming them traditionally, our fixtures team used a microcontroller embedded in the hilt of the saber for the control of each pixel. This microcontroller had cues pre-programmed that could be triggered via DMX. Each saber now only needed six channels to control it. Now all the sabers and pixel props on set, in any given scene, could fit in a single transmitted CRMX universe — reducing the RF congestion on set and simplifying the overall deployment of wireless props in general.

In addition to “blade intensity,” “red,” “green,” “blue” and “white,” the preprogrammed cues included chase-like effects, where the pixels emulated the “ignition” and “dousing” — i.e., extension and retraction — of the blade.

Steelberg notes that the familiar streaking and sparking effects were accomplished in post.

In regard to the sabers’ illumination, he adds, “Just because we could light up the lightsabers, we didn’t want to have lightsaber light everywhere. I think it’s more effective if you only feel the light when it gets really close to somebody’s face, the hum gets louder, and you feel that heat, that energy. By setting the intensity by eye, based on distance to an actor’s face — i.e., making sure a saber started to light a face at about 1.5-2 feet away, but not while it was held at arm’s length — the light from the saber would come and go across faces, mirroring the danger

Says Tran, “We never augmented the light from lightsabers during fights, and even when the performers had their lightsabers close to their faces during a pause, I would ask them to hold it at a specific angle for lighting. For example, in the final confrontation between Ahsoka and Anakin in the World Between Worlds, when she claims his red lightsaber, I asked Rosario to hold the red lightsaber at a specific angle in order to light Hayden’s face.

The eyelight cast from the lightsaber augments his [yellow] Sith eyes, and when we reverse onto her, you can also see a hint of Sith. Most of the environments we filmed in were lower key, so the sabers could take center stage.”

World Between Worlds

All eight episodes of Ahsoka were previsualized before the first day of shooting, so the filmmakers knew exactly how each scene would be shot: on the OSVP stage, on a practical stage with chroma-key backgrounds, or outdoors. Shooting in the OSVP stage was not always a matter of course, notes Tran. “In Episode 5, we actually didn’t incorporate the volume at all,” she says. “We planned to use so much atmosphere that it was going to milk out the image on the LED wall.” Other reasons for eschewing the LED wall, she adds, were the use of “practical fire, and the camera being extremely low- or high-angle.”

In this episode, “Shadow Warrior,” Ahsoka enters the World Between Worlds, a liminal plane of reality where she revisits decisive battles from her past and confronts the ghost of Anakin.

“I asked Rosario to hold the red lightsaber at a specific angle in order to light Hayden’s face.”

Along with ILM visual-effects supervisor Richard Bluff and on-set visual-effects supervisor Justin van der Lek, Tran researched Solo (shot by Bradford Young, ASC; AC July ’18), in which grayscreen was used instead of green- or bluescreen for a sequence that required an intense level of atmosphere, because it was going to be easier to extract and composite in the background. “That’s how we came to use grayscreen for the attack on Teth and Ryloth sequences that take place during the Clone Wars,” says Tran, who styled the dusty battle sequences after those in Akira Kurosawa’s Kagemusha (shot by Takao Saitô and Masaharu Ueda).

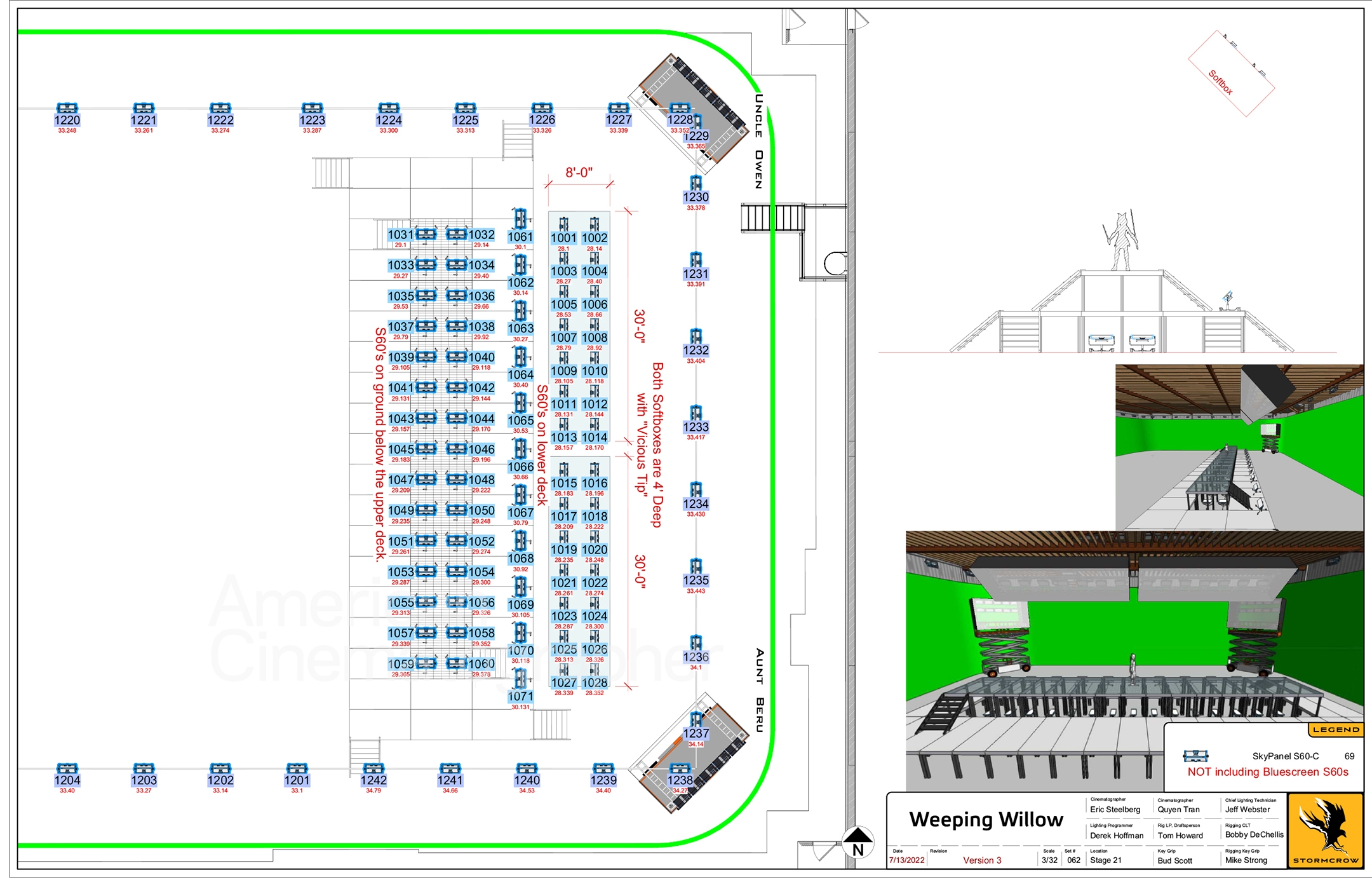

“The battles required very intentional, well-placed lighting in order to achieve the silhouettes we wanted,” she adds. To accomplish this, she rigged the stage with DMX-controlled “Arri [SkyPanel] S60-C [soft boxes] as overhead ambience, with placement scattered across the whole length of the set, which encompassed an entire stage. We had seven different 30-foot trusses with eight SkyPanels circling the perimeter, which acted as backlight and explosion interactive. We used a range of Kelvins to represent explosions, a general ambience of a special purple that I tested months before with Dave.

“On the ground, in addition to propane-flame poppers, we peppered the perimeter with Arri SkyPanel S360-Cs as well as Creamsource Vortex8s — both single units and [four-unit rigs] mounted in frames — for perfectly timed explosions. We hid as many of the units [from] camera as possible using grayscreen blockers, placed [in] shot, so that while we were shooting, the light just disappeared into the mist.” (Tran notes that for other sets, the SkyPanels provided reds, oranges, blues, yellows and greens.)

Additional lighting tools that helped achieve the battle effects included two performers with lightsabers and “solid frames to cast large shadows, which would be replaced with AT-AT walker shadows.”

A camera car was used as well, she says. “For tracking shots, we used what was essentially a modified electric four-wheel-drive Polaris with two cameras mounted on it. We used this vehicle to track and lead the action of Anakin, Ahsoka and Stormtroopers charging into battle.”

Offering an additional example of an effect aided by the SkyPanels, Tran points to a sequence in a different setting within the World Between Worlds: “On [planet] Mandalore, when Anakin says, ‘Incorrect,’ to young Ahsoka [Ariana Greenblatt], the green/cyan and pinkish hues turn red, and the ambience overhead drops out for a silhouette. At this point, Anakin’s eyes turn Sith, so I wanted to augment that narrative.”

Another crucial moment sees Anakin emerge from a fog bank with his red lightsaber and flash into Darth Vader briefly before he attacks Ahsoka. Tran explains, “In order to coordinate that perfectly for the timing, I put LED markers on the ground, so Hayden and the actor playing Darth Vader [Tom O’Connell] had to walk along the same path.” She notes that LEDs served a dual purpose on the atmosphere-filled stage — to both assist the talent in easily identifying their marks and to help VFX track the shot in post.

Speeder Chase

Whenever the filmmakers found themselves approaching a familiar scenario from the franchise’s visual lexicon, there was an attempt to vary its presentation. In the first Ahsoka episode (“Master and Apprentice”), it was a speeder-bike chase between Commander Sabine Wren (Natasha Liu Bordizzo) and a couple of New Republic escort fighters on a Lothal highway. Though this was set on the open road, the scene would surely remind Star Wars enthusiasts of the speeder-bike chase through the Endor forest in Return of the Jedi — especially given the close-up of Sabine’s foot hitting the accelerator, which specifically recalls the original sequence.

For the new chase, Steelberg tapped his experience shooting car commercials. “With speeders, the longer you have them composed steadily within the frame, the more it looks like somebody’s just sitting on something that’s stationary, so I told Dave Filoni that if we treated this like a car commercial, as if we were on a camera car shooting a motorcycle moving at high speeds, there would be a ton of wind and we wouldn’t be perfectly in sync,” he recalls. “Sometimes the motorcycle would get ahead, sometimes the car would get ahead. They’d get closer, they’d get farther apart. The bike’s bouncing up and down on its suspension. It swerves a little bit when the rider looks over their shoulder. The camera would shake.

“We were shooting it on a backlot against bluescreen, with a speeder bike mounted on a stationary gimbal made by SFX, which could raise, lower and bank the bike.”

“But, of course, we weren’t going to be doing this for real, we were shooting it on a backlot against bluescreen, with a speeder bike mounted on a stationary gimbal made by SFX, which could raise, lower and bank the bike. So, how do you create that look?”

Steelberg notes that Bordizzo’s long hair at this point in the narrative would “sell wind,” so they amped up the fan-supplied gusts. The next step was to “get the camera on a device that makes it feel handheld and buffeted by wind.” The cinematographer opted for “a Libra head with a handheld sensor in lieu of wheels, which was able to ‘mimic’ the operator’s movement, creating a tunable handheld look,” he says. The unit was “used by A-camera operator Simon Jayes for the handheld feel, while remote-head technician Jule Fontana used a ‘shaker box,’” which was incorporated into the rig.

The device was connected to a Mini Scorpio head on the end of a Scorpio 45 telescoping crane swung by A-dolly grip Diego Mariscal and crane operator Derlin Brynford-Jones to create the feel of flying down the speedway. “We would move the camera relative to the bike so they look like they’re reacting to each other, moving closer and farther away,” he continues. “On set, we wouldn’t fully rehearse what the camera was going to do. Simon would talk to Diego or Derlin while we were shooting, and that created a bit of lead and lag, which produced a more spontaneous feeling.

“Another way to sell movement on a highway is when you go from old asphalt to new asphalt to concrete, the fill light from underneath changes, so I put bounce cards and duvetyn underneath the speeder and had some grips articulate them,” he adds. “In the scene, you can see the soft-light reflections subtly changing on her skin and visor.

Daylight and Deep Space

Whenever possible, both cinematographers strove to shoot scenes in real sunlight for day exteriors. For instance, later in Episode 5, in the clouds above Seatos, Ahsoka walks onto the wing of her shuttle to communicate with a pod of spacefaring whale-like “Purrgils” and the sun comes out as one of the creatures floats up to the wing.

The wing was built full-scale and mounted to a rotatable platform on the backlot. Tran deployed large Ritter fans capable of producing 40 mph winds from 15' away and large negative fills for the Purrgil shadows. “When Ahsoka walks out onto the wing and summons the Purrgil, I wanted to feel the negative fill of the Purrgil rising to meet her eye to eye. To achieve that, we had two handheld 12-by-20 solids that we walked toward Ahsoka, mimicking what might happen if a Purrgil were to come close.”

“There’s just something about the intensity of real sunlight that brings out the texture of skin and wardrobe,” she adds, “and it made these specular hits off of the wing, which you couldn’t really emulate perfectly [with movie lights], even on a big stage.”

Tran adopted a different approach for the deep-space scenes set in the shuttle’s cockpit and gun turret. “In space, it’s all hard light out there that comes in through the ship’s windows, because there’s nothing for it to bounce off of — so I needed a hard source with enough punch that could also move quickly as the ship maneuvers and the lighting angles change,” she says.

Furthering this light requirement was the fact that the cockpit of Ahsoka’s T-6 ship was built on a bluescreen and mounted on airbags (the latter because it was “too large and heavy” for a gimbal, Tran says). Even with the cockpit’s ability to move via the aid of the airbags and the work of the SFX crew, using a fixed light source wouldn’t produce the dynamic changes in illumination she wanted for the big space battle in Episode 3 (“Time to Fly”).

“We ended up putting a 900-watt Fiilex Q10 LED Fresnel on a telescopic crane,” Tran says. “I had operator Michael Schmidt on a Power Pod head and Derlin Brynford-Jones on the crane arm. Sometimes we’d use Chroma-Q Studio Force II LEDs around the cockpit to emulate blaster fire to help sell the effect. I’d tell them, ‘We’re gonna roll to the right,’ and everyone would coordinate the timing together. 1st AD Kim Richards would count down, so everyone — crane operator, lamp operator, SFX and actors — knew which direction to lean. It took a real team effort to bring it all together.

Uncommon Collaboration

Tran and Steelberg shared credit for shooting Episodes 2 (“Toil and Trouble”) and 7 (“Dreams and Madness”), and they regularly ran tandem units or shot pickups for each other’s episodes. (Paul Hughen, ASC also contributed several shoot days as 2nd-unit director of photography.)

Says Tran, “I did the research for the cockpit and the World Between Worlds, which, even though it appears at the tail end of Eric’s Episode 4 [‘Fallen Jedi’], features more prominently in my Episode 5. But I wouldn’t have had time to do any of that had Eric not researched other aspects of the show for me.”

Steelberg points out that Ahsoka was the first time he’d worked so closely with another cinematographer. “It was a fantastic experience learning from Quyen,” he says, “sharing with her, and finding solutions that worked for both of us.”

Tech Specs

2.39:1

Camera | Arri Alexa LF

Lenses | Caldwell Chameleon SC, Cooke Anamorphic /i FF

A Classic Cockpit Look

In pre-production, Filoni mentioned to Tran that he liked the way the Millennium Falcon cockpit was photographed by Gilbert Taylor, BSC for A New Hope, and he wanted the same framing for Ahsoka’s shuttle. At Tran’s suggestion, he produced copies of the original camera reports taken by camera assistant Madelyn Most for all the cockpit scenes in that film. The reports revealed that Taylor had shot the scenes with either a 40mm or 50mm anamorphic. “I tried to stick to those two focal lengths so that my scenes would have that same feel,” she says. — Iain Marcks