Life Goes on Location in Africa: Katie and Bogie Hit the Congo

Photographer Eliot Elisofon’s exclusive report from the set of The African Queen — just one of many exceptional tales in the book Life. Hollywood.

Life magazine’s coverage regularly included unique and often exclusive perspectives on motion-picture production, and the curated and carefully researched 708-page collection Life. Hollywood — featuring hundreds of remarkable images culled from decades of the magazine’s archives — delivers an outstanding visual overview of film history, not only featuring Hollywood’s biggest screen stars, but many of the filmmakers working behind the scenes.

Also included in the book are details on the contributing still photographers who were instrumental in making Life special and still memorable today.

The following excerpt is the first of two that the publisher has generously supplied to American Cinematographer to share with our readers.

While he is not featured in this coverage, it was, of course, Jack Cardiff, BSC behind the three-strip Technicolor camera on The African Queen for director John Huston.

Images and text courtesy of Taschen. All photos TI Gotham, Inc. © Life Picture Collection, Meredith Operations Corporation.

John Huston’s The African Queen

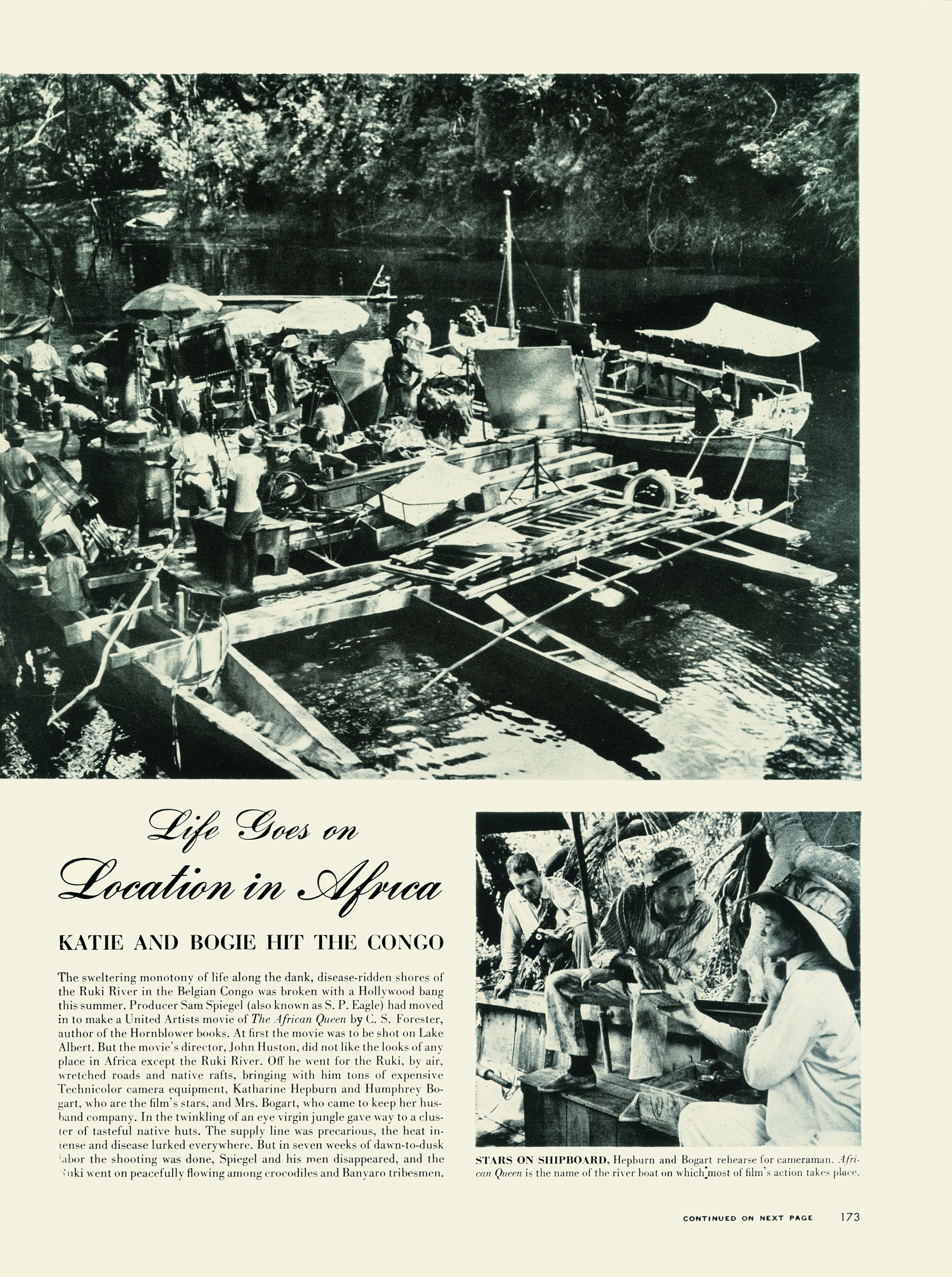

“RAFT ON THE RUKI RIVER WAS HEADQUARTERS FOR 40-ODD SWEATING MOVIEMAKERS”

September 17, 1951

In 1950, when John Huston transported Katharine Hepburn, Humphrey Bogart, and his crew to the Congo to shoot The African Queen, many in the movie industry considered it not simply impractical but folly. This tale of a prim spinster (Hepburn) thrust into a wild riverboat journey with a scruffy, hard-drinking boat pilot (Bogart) could have been much more cheaply and easily shot on a studio backlot. Huston, however, loved filming in far-flung locations, and those naysayers were all wrong: The film was a critical and popular hit and remains a classic.

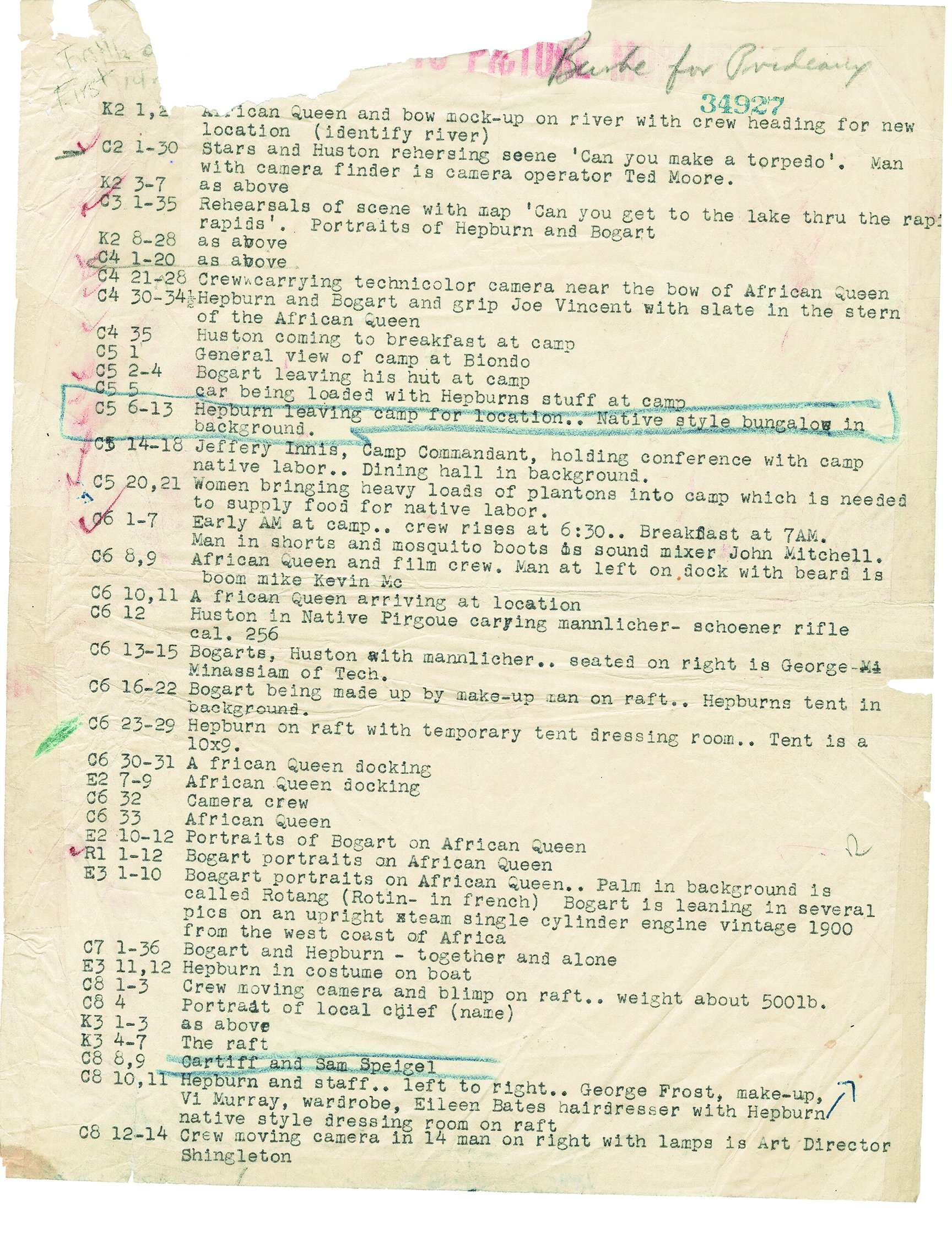

Unlike much of the film’s cast and crew, Eliot Elisofon, Life’s photographer covering the film on location, was no stranger to Africa. He had covered the war in North Africa and, in 1947, began making photographic pilgrimages throughout the continent. Elisofon would make approximately 11 such excursions, documenting African people and cultures as they seldom had been in the Western world.

The African Queen’s production was arduous, involving every hardship imaginable. As Elisofon snapped hundreds of images of the stars, their director, and his company, Huston developed an affection for the photographer and his work. In his autobiography, An Open Book, Huston wrote: “Eliot Elisofon was a supreme egotist. He made no bones about it: he was the greatest photographer alive. With Eliot, you didn’t know where innocence left off and egotism began. I liked him enormously and found him quite unbearable.”

As was so often the case in Life, few of Elisofon’s numerous photos saw print. The African Queen photo-essay, subtitled “Katie and Bogie Hit the Congo,” focused mainly on the ruggedness of the film’s remote shoot. Although Elisofon took many strong, straightforward portrait shots of Bogart and Hepburn, Life’s editors instead cleaved toward images of the film’s company adapting to life in their camp, which was rough-hewn from the jungle. The article was focused on anti-glamour: Hepburn, for instance, is shown being doused with bucketsful of water to clear the “dirt and insects” from her hair.

Elisofon’s working relationship with Huston continued beyond The African Queen. In his work, Elisofon used color filters intended for film production, so Huston hired him as a color consultant on Moulin Rouge, his biopic of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. This subsequently led to similar positions for him on films like Bell, Book, and Candle and The Greatest Story Ever Told, both of which, appropriately enough, Elisofon also covered for Life.

All photos by Eliot Elisofon, Congo, Africa, 1951.

You’ll find more information about Life. Hollywood here.