The Fly — New Buzz on an Old Theme

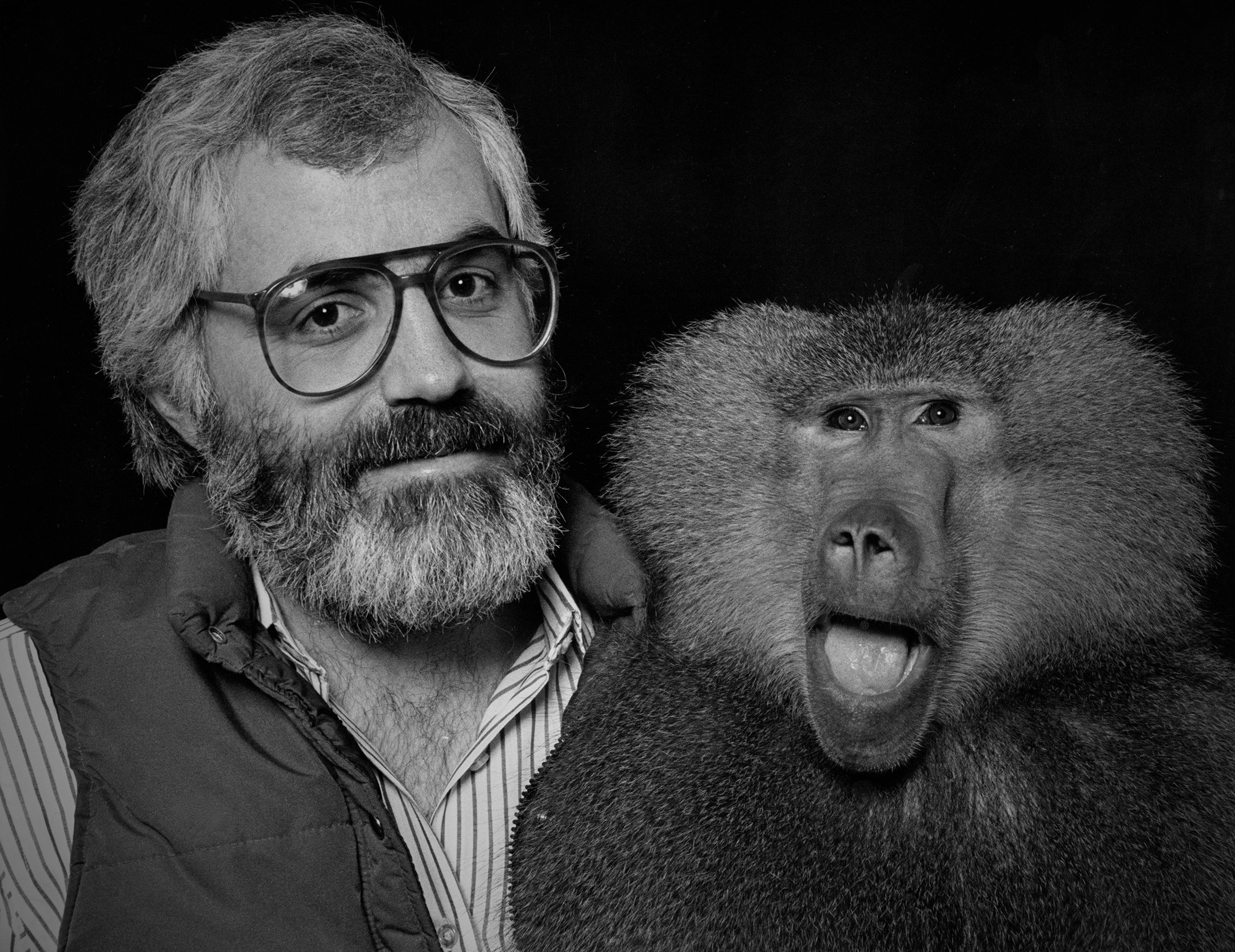

Mark Irwin, CSC details his experience working with frequent collaborator David Cronenberg on this horror masterpiece.

For nearly a decade, Canadian screenwriter-director David Cronenberg has been hailed for ambitious, intelligent, biologically oriented horror films. Cronenberg’s first two features, They Came From Within (1976) and Rabid (1977), were acclaimed for their wild energy and audacity, but it was not until he teamed with cinematographer Mark Irwin, CSC that his oeuvre began receiving serious attention for its style and sensuous imagery. Their horror feature collaborations — The Brood (1979), Scanners (1981), Videodrome (1982) and The Dead Zone (1983) — furnish a corner of the genre that’s entirely their own; taken together, they constitute an impressively mature, occasionally satirical study of how the world around us, or just around the corner, may eventually alter the human species.

Their latest work, The Fly, a Brooksfilm production, is more of a re-think than a re-telling of George Langelaan’s famous story, which was almost literally filmed in 1958, from a script by James Clavell. The new script, by Cronenberg and Charles Edward Pogue, again deals with the achievement of teleportation, a process of molecular disintegration-reintegration that will make travel instantaneous and all existing modes of transportation obsolete. A fatal error occurs when its inventor, Seth Brundle (Jeff Goldblum), teleports himself without noticing that a fly has flown inside the teleportation chamber (or “telepod”) with him.

In the original film, the experiment gave scientist Al (David) Hedison the head and claw of the fly, and vice versa, whereas the new version genetically fuses the two life forms into one insidious entity. The teleportation test is initially an intoxicating success, with Brundle exiting the pod “feeling like a million bucks” and capable of extraordinary gymnastics. Soon after, the fly’s unsettling physiognomy and digestive habits assert themselves (courtesy of the Chris Walas-led makeup effects team, of Gremlins fame), and the film chronicles the tragic results with an unflinching eye.

The Fly is Irwin’s 19th feature as director of photography in 11 years. His prematurely gray hair and beard refute the fact that he was born as recently as 1950, seven years later than his director, whose work he first admired while a student at the University of Waterloo. Majoring in kinesiology (“a highbrow way of saying ‘physical education’”), Irwin entered a film course and attended a screening of two early Cronenberg efforts, Stereo (1969) and Crimes of the Future (1970). “These particularly impressed me because he wrote, produced, directed and shot them, and still managed a very dynamic visual style,” Irwin recalled. “I was struggling to do those things myself and had found that, when shooting something well, some of the other responsibilities sometimes suffered for it. Working with him now, I try to keep David in touch with those elementary roots of Stereo, because he’s grown and become insulated from them as the years have passed.”

Irwin later made his appreciation of the two films known to the fledgling director at a business meeting, but the connection was dropped until he found himself third on a short list of cinematographers that Cronenberg considered for Fast Company (1977), a little-seen drag racing opus to be filmed in Edmonton, Alberta. “The first guy turned it down after agreeing to do it and the second choice couldn’t leave Toronto for Edmonton, so I found myself on a plane the day before shooting began, not knowing what to expect,” Irwin said. “After working together for about a week, we realized we were speaking the same language, perhaps because I’d convinced him that almost everything I knew had come from seeing his films!”

“Another director told Mark [Irwin] that the fact that he’s worked for the same director six times in a row is really remarkable.”

— writer-director David Cronenberg

Since those early days, Irwin has developed an extraordinary reputation within the Canadian film industry. In addition to his well-publicized work with Cronenberg, Irwin is the current president of CAMERA (Canadian Association of Motion Picture & Electronic Recording Artists), and an award-winning documentarist.

“I haven’t seen a lot of the work Mark has done with other directors, but what I have seen seems to be quite different than our work together,” Cronenberg offered. “Another director told Mark that the fact that he’s worked for the same director six times in a row is really remarkable. It’s something that rarely happens — in North America, anyway; it’s much more common in Europe. So I like to think that we’ve formed, with our art director, Carol Spier, a kind of European-styled triumvirate of sensibility and professionalism. We try to evoke, and provoke, the best from each other. We encourage each other to experiment, to dig deeper, to go crazy. We trust each other’s instincts; if one of us is upset by a suggestion, which isn’t often, the other assumes there must be a very real reason behind it, so we talk about it.”

Irwin’s work on The Fly may yield some dreamily beautiful images, and a good deal of deliberately revolting ones, but it was never intended as an obvious, stylistic tour de force in the same sense as Videodrome (for which he was awarded the 1983 Best Feature Cinematography CSC Award). Instead, the film reflects the yeoman efforts of a cameraman taking pains to work as invisibly as possible, while extending the same grace of invisibility to a large and ever-present effects crew.

“The main thing in films like these, for me, is not to give them away as horror films in terms of lighting.”

— Mark Irwin, CSC

“The main thing in films like these, for me, is not to give them away as horror films in terms of lighting,” Irwin defined. “I’ve found that you can make every scene dark and gloomy and weird and scary to the point where the truly dark and scary scenes can lose their value. So, quite often, I will light a scene to favor the less menacing characters, to offer the audience the relief that it needs to appreciate the next plunge into the sinister mood. In other words, they’re pulled away only to be thrown back in again.” This complements the same principle of counterpoint as Cronenberg’s use of urbane, decidedly amusing dialogue, which enhances a situation’s believability while relieving the audience of a film’s most strenuous moments.

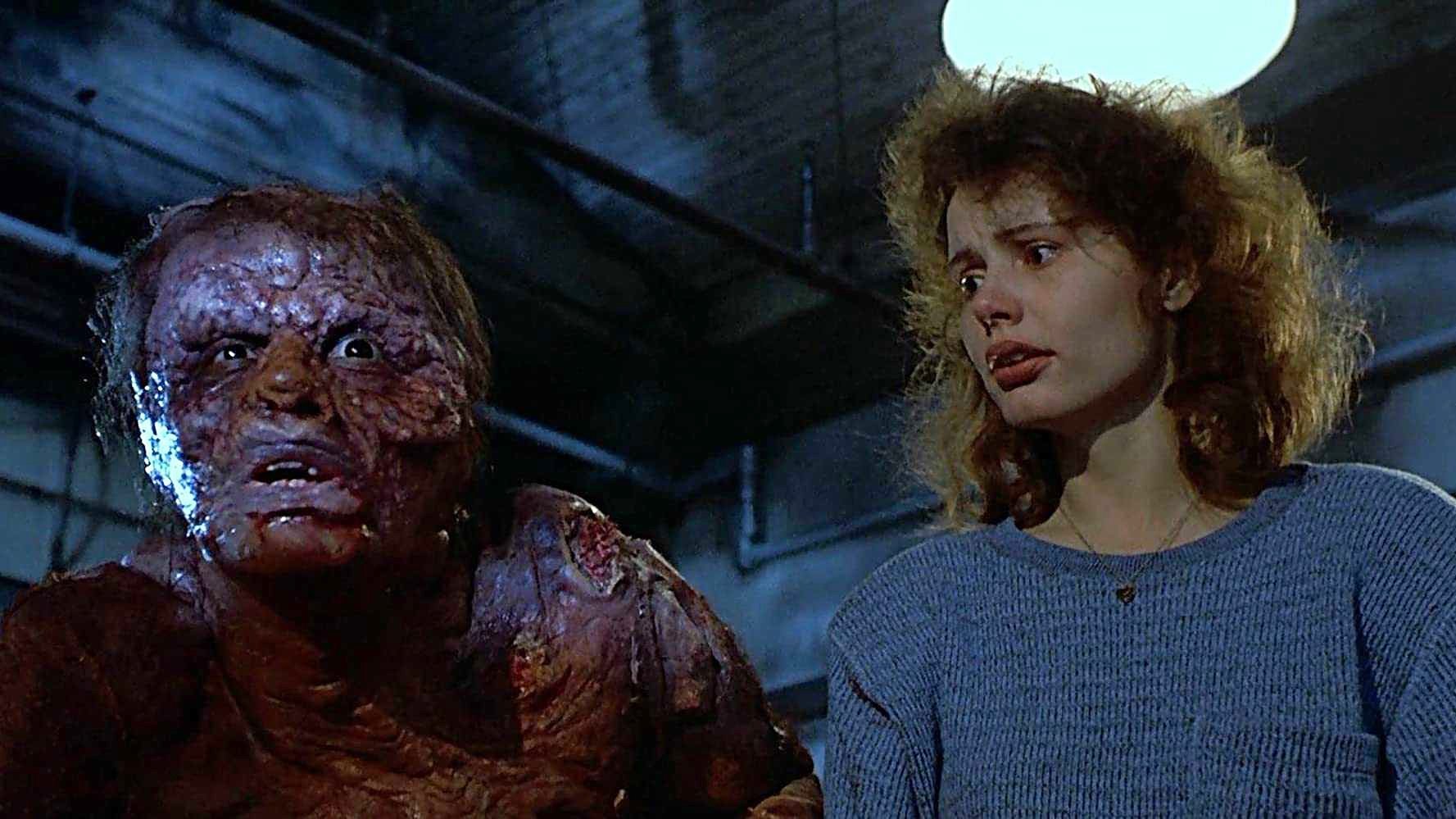

“The Fly opens with a skeptical journalist [Geena Davis] being drawn into a laboratory by a quirky, awkward scientist who’s hoping to seduce her,” Irwin said. “It’s a warm situation, so the lighting begins warmly and directly but, after the hero teleports himself, the lighting becomes more severe on him. I never changed the lighting on Geena because she is the one sympathetic character, who starts out skeptical, then trusts him, then believes in him, then falls in love with him, even though he’s changing before her eyes. The mood I hoped to create was one of sympathy, as seen through her eyes when she’s with him but, when he’s alone, the lighting can’t sustain such an upbeat note.

“Jeff’s [Goldblum] makeup goes from a basic Caucasian skin tone through yellows to ochers to copper and brown, and finally almost black, with lots of strange hairs, metallic green warts and pads for sticking to walls and ceilings, and I tried to keep the same lighting with variations and as much cross-lighting as I could, to make the makeup definitions work,” Irwin continued. “The hardest thing about this film for me was lighting a latex suit that kept changing every day in different directions. The final stage is a full-blown, sculptured puppet and, since the modeling is three-dimensional, I was able to back off on the exaggerated rim lighting. We shot things out of continuity so that, one day, Jeff would be wearing the heaviest, darkest, most light-absorbing, purple-red-brown costume, and then we’d go to the Stage 3 puppet, then to Stage 5 or back to Stage 1, and it was hard to know how much or how little light to train on it. I was always aware of the absorption factor with dark-brown latex and I had to front-light it quite a lot, yet I didn’t want to reveal too much, so I used a lot of gobos and colored light. The distorting contact lenses made his eyes so deep and dark that I had to fight to get light into them. Jeff was great, because he knew what I was doing and he played toward that.

“The hardest thing about lighting the puppet was that it was neither skin nor anything approximating the color or texture of skin, so anything I knew about lighting people was of no value. I find that spot meter readings are upsetting, so I set my key and use my eye from there. The lighting has to maintain a mood and, though I’m always reluctant to use horrific, ‘monster-style’ lighting, in this case I had to. We conveniently placed a lot of light sources, one of which was a work light that’d been knocked to the floor, which then key lights a lot of the action in the last reel.”

Naturally, when the two characters share the frame for several emotional scenes, Irwin was challenged to find a means of blending the two lighting styles without confusing their individual associations. “All of the Fly scenes also feature a human,” Irwin explained. “Over-the-shoulder and clean shots are fine, obviously, but when you have the human and fly characters framed side-by-side, or face-to-face, it’s very hard to maintain the difference. Geena has a very pale, smooth complexion and definite features that I had to flat-light or soft crosslight but, when Jeff’s in frame too, I had to flag and net and crosslight to make his makeup come alive, because so much of it was painted rather than sculptured.”

“I’ve never been a stickler for so-called realism — not in my dialogue, my characters, sets or lighting.”

— David Cronenberg

The thoughtful result is that of two characters who reflect sane, caressing balances of light when apart and whose combined chemistry knocks the atmosphere askew. The film’s third person, Veronica’s editor and former boyfriend, Stathis Borans (John Getz), was given a scheme not only suggestive of his character’s wily path from smug respectability to jealous imbalance to ultimate heroism, but also of Veronica’s growing dependence on him. “I was trying to keep John as a shadowy, sinister character almost until the bitter end, when he comes to Geena’s rescue,” Irwin described. “The lighting on him becomes more honorable and heroic, as it becomes more sinister on Jeff; it’s a simple thing, and the two inversions, these two crossed attitudes, come across subconsciously.”

Both Irwin and Cronenberg bridle at the suggestion that such deliberate lighting schemes give The Fly a “stylized” look. As Cronenberg explained, “I view this as realistic lighting to a point, but then I’ve never been a stickler for so-called realism — not in my dialogue, my characters, sets or lighting. When you look at the so-called ‘realistic’ films of the 1930s and ’40s, like The Grapes of Wrath [shot by Gregg Toland, ASC], they look biblically stylized in every conceivable way. I don’t believe there is any such thing as realism in movies; the only realism in movies is the style one naturally evolves over a period of time.”

Early conversations between Cronenberg, Irwin and producer Stuart Cornfeld volleyed the notion of shooting The Fly’s optical effects sequences in VistaVision. It was finally decided that full-aperture 35mm was good enough. “The difference was going from 5247 to 5294,” Irwin explained. “So we reached the point where, if we considered doing an optical, we had to do it at 5247 [100 ASA] to guarantee that we didn’t have a generation difference, in the case it was used. If we didn’t, we still had to make it a generation different to make it look like 5294. [Director] Phil Borsos’ experience on One Magic Christmas was that his producers decided VistaVision wasn’t worth the expense, so they shot all of their opticals in 94. In other words, when the optical comes out, it’s got at least two generations on top of it, right next to something that’s 94. Whereas, if we take 47 and degrade that as much as any optical process would, cut it back next to 94, it looks like 94. You don’t see it. If we’re doing any kind of an optical, it’s my job to prepare the pathway so it doesn’t show up. When you see the grain coming up in a movie, you can always tell that a freeze-frame’s coming. I don’t want to set the audience up and then reveal what’s going to happen in the cut preceding it.”

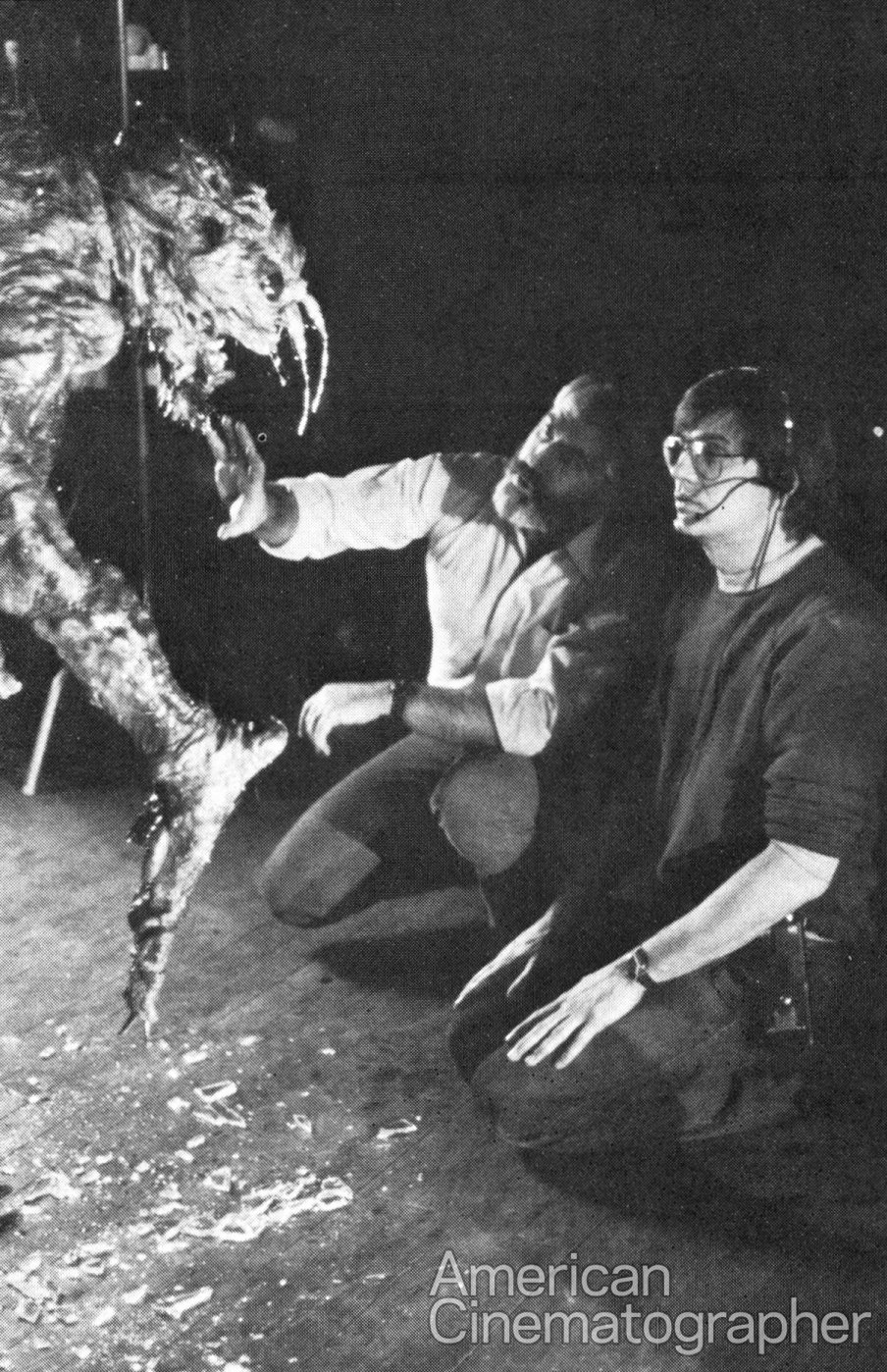

Even more crucial to the film’s overall sleight-of-hand was Irwin’s cautious navigation of Chris Walas, Inc.’s on-set special makeup effects, which bridge the various stages of Brundle’s transformation from a full-body, latex costume to an array of puppetized body components. The arrangement made filming in standard 1:85, with its embodied TV and Academy frame lines, a veritable juggling act. “When you have prosthetics and puppets, with 10 guys and their cables everywhere, you have to frame them all out of everything — certainly out of TV, since that’s where the film’s longest life will be. It’s always a hassle trying to get a long shot in 1:85, while keeping the other frames clean. We were adding, subtracting, dividing, shading and draping velour and false tissue to make the puppets work in all three framelines.”

Additionally, though dramatic lighting was essential, hard lighting was impossible due to the endless possibilities that telltale shadows might be cast, blowing the whistle on Walas’ hair-raising effects rigs. It was here that Irwin made use of a special lighting cabinet he first designed for use in Peter Markle’s Youngblood.

When Irwin was signed to Youngblood, Markle’s instructions to him were to avoid everything that resembled conventional TV hockey coverage, insisting that most of the footage be shot directly on the ice. “A friend of mine, a fellow cameraman, had just done another hockey film using scoops, and ended up using about 200 of them, which took almost a week to rig,” Irwin recalled. “Youngblood had to be covered everywhere, and I had to light everything to 120 foot candles to shoot slow-motion, 96 to 120 frames, at any time, in any corner, and that can lead to some very flat lighting.” Irwin’s reputation for delivering source-lit compositions with character, clarity and speed was already challenged.

The answer came when Irwin noticed the sailmaker’s shop next door to his camera equipment rental house. He commissioned a series of Dacron sailcloth skirts from the neighboring tradesman, with which to experiment. These, when Velcro-fastened around a shallow boxed arrangement of 10 5K Skypans, inspired the creation of the “Mi-Light” (MI for Mark Irwin). An Mi-Light is a 4'x4' box of aluminum framing with two layers of Dacron sailcloth — spaced 9" apart — and four softlight bulbs beaming through both layers. This virtually shadowless light source is, thanks to its aluminum structure, light enough to mount on a ceiling and, being only 18" in width, narrow enough to fit the tightest locations.

“On Youngblood, I needed these lights to fill a large area — like a bench that’s 30' long — when I had to work quickly and in a small space, like those tiny locker rooms,” Irwin described. “The Mi-Lights are really an extension of all the lights I’ve tried, built and have had custom-made. It’s an effort to find as smooth a light as possible for the least amount of space. Working with David, I’ve never used fog filters because he doesn’t like them. I’ve been able to use different filters, nets on the back elements and smoke when working for other directors, but I’ve been trying to achieve a certain softness in my work with David, solely through lighting.” On The Fly, Mi-Lights were used to crosslight the laboratory for effects scenes that may well have revealed cable shadow if lit by more traditional means.

The lab, which doubles as Brundle’s cramped living quarters, was one of the most restrictive factors for Irwin, as 80 percent of the film’s action was staged there. “I’ve never had one set that’s been as crucial to a movie as the lab was to The Fly,” Cronenberg said. “It is the universe for this movie, so I wanted it to have four seasons, days and nights, different tempers, atmospheres and temperatures, so that it would be continually alive and interesting.” Thus Irwin had to exploit the available space fluidly and creatively.

Irwin felt he could best expand the set by using an Arriflex 35 BL, which offered a “smaller, more user-friendly” size and shape than a Panaflex, enabling him to squeeze into all available spaces; not to mention its wider array of distortion lenses, which allowed Irwin to provide illusions of depth to cramped areas. But tactile considerations led to the second of Irwin’s Fly innovations.

“Art director Carol Spier designed the laboratory set with a real floor,” Irwin explained. “I tried suggesting that she use paint to create surface gouges instead of crowbars, because crew members were making bumps that I would have to deal with later. For location or rough interior shots, I tended to use a Western dolly, but you can’t push them very well. They pull great but, as you know if you’ve tried pushing any wagon with rear-wheel steering, they fishtail all over the place. Over the last couple of years, we’ve been using Chapman’s PeeWee dolly fairly exclusively, for 16 and 35mm shooting, so I decided to try pneumatic wheels on it.”

Irwin had done some similar dabbling with dolly structure and movement during Youngblood. “On that, we used everything we could find to move the camera,” Irwin recalled. “I did a lot of handheld shots with two grips pushing me with a grip pipe around my waist, like a big wheelbarrow. We used a little lawnmower type of dolly that let us put the lens about an inch above the ice. We used a wheelchair for some if it, and designed our own Western dolly with double-skate blades that could crab; we did Figure 8s with that thing. For The Fly, Chapman wouldn’t authorize our changes, so we had to obtain written permission. We searched and, finally, my key grip [Mark Manchester] found wheels that would fit inside the hubs; the final result was double-wheeled with eight soft rubber tires. [These were additionally smoothed and cut along the tread so that they could track accurately, as during certain line-up shots requiring brake precision within 1/2" or 1/4".] The result won’t look any different than a conventional dolly shot but, the vibrations we would’ve picked up without the pneumatic tires, to me, would’ve made those shots unusable.

“When I saw White Nights [shot by David Watkin, BSC], I saw a lot of crabbed dolly moves on this obviously real dance floor, and they jumped, vibrated and didn’t hold frame,” Irwin recalled. “It was hard to watch, even for some laymen, I’m sure. They must have had a PeeWee, a Hustler or a Fisher with hard wheels and, tracking really fast over those boards, it showed up. All we did was replace those wheels and we could track at any speed, and it was dead smooth. It also gave us the freedom to move forward, diagonally or lead someone for 40 to 50 feet, without the actor having to step between track or myself having to cheat with my angle to avoid seeing track as it spans out behind them. The freedom for my director is also much broader, because I don’t want to tell him where he can’t go with the camera. So I’ve drawn out of this a dolly I can use on location, even though it was built for a studio that was built to be like a location. It’s a backward route, but I got there!”

The pneumatic tires make all the difference in the finished film. The laboratory scenes have a lush, almost levitated feel to them and, remarkably, considering the spatial limitations, Spier’s set afforded Irwin only one removable wall — offering a wider access into the bedroom area — which was seldom used.

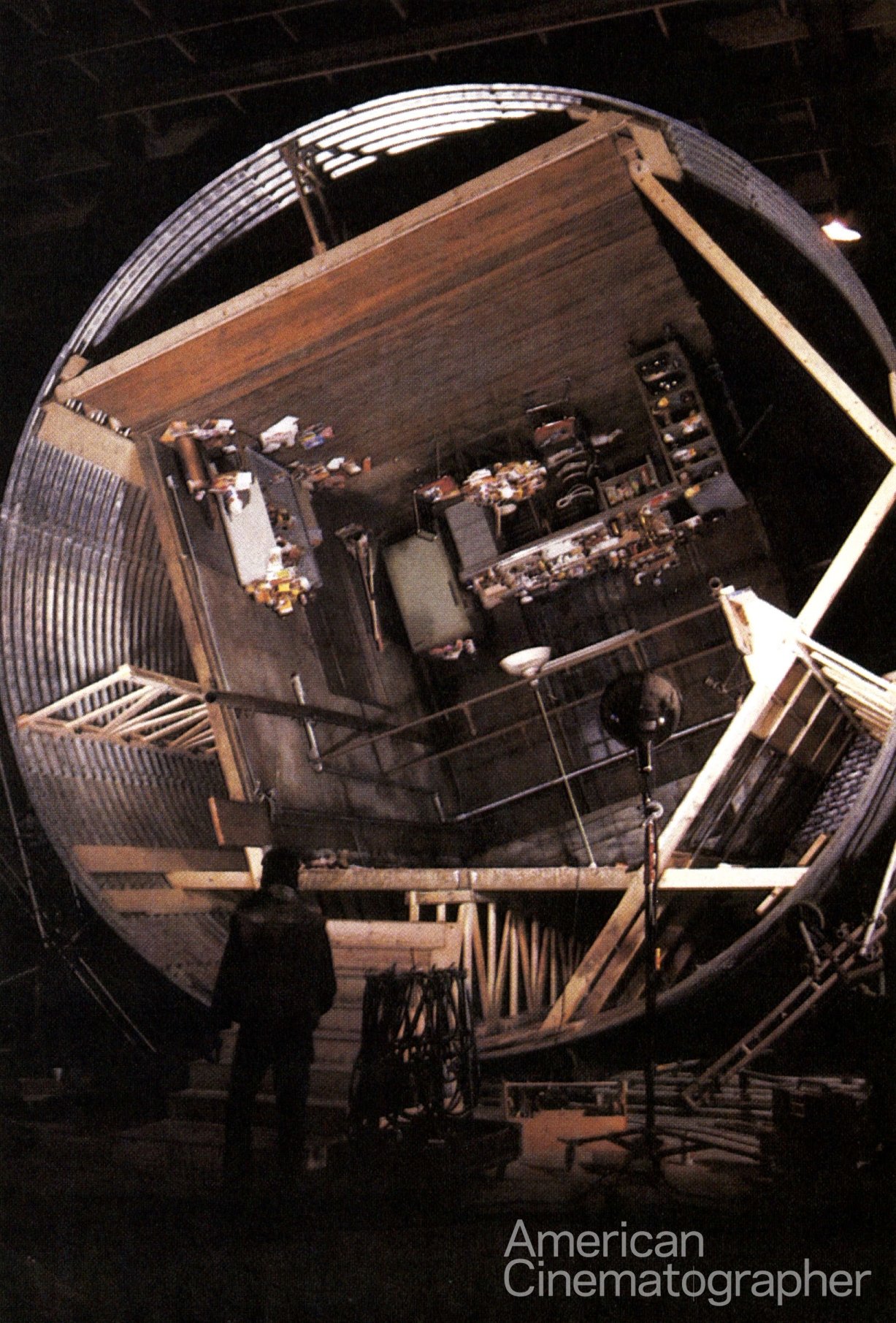

The kitchen and skylight sections of Brundle’s lab were remarkably replicated inside a revolving 28' culvert steel cylinder for those shots in which the metamorphosing scientist scales the walls and ceiling with his bare hands. The difficulties imposed on construction manager Kirk Cheney were considerable (the set had a large window where the axis had been concealed on every other revolving room ever filmed, from Royal Wedding to A Nightmare on Elm Street, necessitating a major redesign), but Irwin had to light the environment. “Because of the lighting necessary for the Fly makeup, I couldn’t use a source light that was soft and smooth; it had to be shadowy and mysterious, “Irwin said. “The trouble was, the rotating stage was not an open cage that offered me exterior space in which to light. When the room was placed inside the culvert, I was left with only 4' in which to arrange very hard, directional light for the area.”

Irwin handled the situation by having the wall opposite the action lined with six 4'x10' plexiglass mirrors, their surfaces patterned with expressionistic streaks of tape. The tape allowed the illumination reflected from a single 10K light, with lens pulled, to suffuse the set with a built-in system of mysterious shadows. The camera operator (who, for this effects insert, was Irwin’s former assistant, Robin Miller) and an associate were placed inside a steel carriage attached to a Ferris wheel-styled brace affixed to the set’s facade, which executed a 200-degree curve apace with the interior. Though the operator was not turned upside down with the room, the camera naturally was, its motions dictated according to the live feed from a video monitor couched within the carriage.

Sadly, one of Irwin’s cleverest passages will not be included in the theatrical release of The Fly. In this scene, Brundle adheres to the outside wall of his six-story warehouse, until a sudden pain causes him to slip down onto a ribbed awning, where a third leg moistly hatches from his side — which he removes with his teeth. This outrageous scene (which is promised for the film’s “unrated” video release version) was accomplished with the help of a 26' tall, 40' wide wall, erected on a 45-degree angle. With his camera mounted on an identically angled triangular block, Irwin photographed the scene in two separate passes from a crane that rode the side of the wall. The wall, which represented only three stories, was then redressed with lamps, pipes and grime to suggest a lower portion of the same wall. “The lighting for that scene was weird,” Irwin said, “because the wall itself went right up to the ceiling grid and, since we’re starting with the top of a six-story building, the moonlight would have to be above that, shining down. I had only 4' to the grid, and I couldn’t put a light above that because of the 45-degree angle, so it became a matter of pulling another light source.” In a very inventive move, the art department appended a portion of an adjoining apartment building to the corner of the wall, each of its three windows providing separate light source and identity. The illusion of extending the space from three to six stories was further enhanced by redressing these adjoining windows with lamps, shades and potted plants.

Irwin’s professional rule amounts to staying busy. Since completing The Fly in April, he has begun filming SCTV’s Twilight Zone parody Tales of the Weird and Wonderful [released in 1987 under the title Really Weird Tales]. “I like to work and used to accept everything,” Irwin admitted. “I’ve done some real turkey films, like Starship Invasions, which is actually in the Golden Turkey Awards book, but these have usually been good experiences and led to good connections with people, which inevitably lead to other, better, films down the road.

“I can remember the guy who turned down Fast Company saying, ‘I don’t want to do a drag-racing film, are you kidding?!’”

Irwin was later invited to join the ASC, and subsequently shot such features as The Hanoi Hilton, The Blob, RoboCop2, Wes Craven's New Nightmare, Dumb and Dumber, Scream, There's Something About Mary, Road Trip, Old School, The Layover and The Retirement Plan.

You'll find his personal website here.