Shooting The NeverEnding Story

The arduous task of creating the effects-heavy creature feature, and lighting one of the planet’s largest bluescreen stages to date.

This article originally appeared in AC Aug./Sept. 1984

“The world needs a miracle,” said Bernd Eichinger, head of Neue Constantin Productions, as he began work on The NeverEnding Story. With a budget set at $25 million, the largest in German film history, this miracle was about to come true. The “miracle” began with the design of spectacular sets, the full range of sophisticated motion picture and video technologies, and with the experience of a staff of 200 specialists — all gathered at Bavaria Studios in Munich to bring to life the fantastic world of Michael Ende’s worldwide bestseller The NeverEnding Story.

I had been offered this project originally in early 1982, while I was working on Das Boot. However, once Das Boot was completed, a very long and very difficult shoot, the prospect of another even longer and even more difficult project, one full of all sorts of special effects, didn’t attract me, and I refused the job. Just over a year later I received a call from my friend director Wolfgang Petersen, who had accepted the job of directing The NeverEnding Story, a film already in production. After the success of Das Boot, and the excellent working relationship we had on that film, I jumped at the chance to shoot the film.

The clock was already ticking when I signed on. A sizable team of specialists had been at work for several months designing and constructing the story’s fabulous creatures. Petersen and I began work immediately with a whole new concept for the film, with a new shooting script, new storyboards, new everything. Storyboards were a new experience for us, necessitated by the enormous number of models, process shots, creatures, effects — all in addition to the regular human actors. From that point on, we sat — Petersen, Rolf Zehetbauer, the art director, and me, gradually seeing the film develop and take shape according to all the new ideas that were brought in.

“We brought life to the project with an incredible assemblage of special effects — 300 bluescreen shots, numerous matte paintings, computer motion control, and many other effects that had never been used togetherin our industry in so great a number.”

The essence of the novel’s storyline concerns Bastian, a small boy, who accidentally becomes owner of a book possessing magical powers. In it, he reads of the magic country of Fantasia, a kingdom endangered by a titanic creature called The Nothing. The kingdom is also under attack by the mighty Rock-Biter, who rumbles through the nocturnal “Haule-Wood” on his bicycle of stone. He reads of Falkor, the dragon of fortune who flies over mountains and oceans carrying the book’s hero, Atreyu, on his back. Atreyu is destined to save Fantasia from destruction. Bastian does not want to admit, as his life becomes involved with the story in the book, that he himself will become increasingly part of the book, and may in fact be the key to the salvation of Fantasia and its childlike Empress. A fantastic story, but one I knew would not come alive merely by assembling the actors in front of my camera, and hearing the director call out: Action!

We brought life to the project with an incredible assemblage of special effects — 300 bluescreen shots, numerous matte paintings, computer motion control, and many other effects that had never been used together in our industry in so great a number, and certainly to so great effect. Without the knowledge and ideas of Brian Johnson, our special and visual effects director, we would soon have been at our wits end. I consider this film a great moment in the history of this kind of motion-picture work. The combination of effects specialists Giuseppe Tortora and Colin Arthur, with their teams, along with the Industrial Light and Magic team was unbeatable. They gave life and soul to the creatures of Fantasia.

Nevertheless, the effects techniques we chose had their drawbacks. Camera movements in particular are restricted. After shooting Das Boot, where 80% of my work was handheld, this shoot was an enormous change, as I really did not have the expressive camera technique of camera motion to bring into the film. It is true that motion-control techniques have made pan/tilt shots possible even with bluescreen (one shoots the foreground, and the computer has the camera repeat all movements with great precision when shooting the background), but the time required for these procedures kept its actual use within rather narrow limits. We found it necessary to create the drama seen in the film more through editing than through camera movement.

A further problem inherent in effects photography is the inevitable loss of image quality with each generation made in the opticals process. The loss cannot be compensated for except by using a negative of larger size. Our ILM unit used, of course, the VistaVision format cameras they have used on every major effects assignment since Star Wars. The horizontally running camera produces a negative with double the image area [of standard 35mm], and ILM shot all our bluescreen work and matte painting plates this way, and did an incredible job considering the time pressures we were working under. We used spherical Nikkor lenses on the VistaVision cameras, as they were particularly well-adapted for bluescreen, due to their optimum correction in the blue range. The anamorphic reprinting process, which was how the VistaVision shots were printed to standard 35mm, followed the production of composite-effects printing.

We used a wide variety of standard motion picture equipment, of course, in addition to all the specialized tools we had. The film was shot with Arriflex 35BL-3 and 35-3 cameras and Zeiss lenses, out of Arri Munich. In addition, the Arri factory handled the adaption of the Nikkor lenses to the VistaVision cameras, and all changes and modifications (and they were numerous) we needed during production. Our anamorphic lenses came from Technovision, lenses made famous by Vittorio Storaro [ASC, AIC]. We also used a Matthews Tulip crane, a Louma crane, and the new Panther dolly, by Schmidle and Fitz of Munich.

We had four separate camera units using all this equipment, my main unit; my second unit under director of photography Franz Rath, who contributed considerably to our success; the model and cloud-tank unit under Jair Ganor; and the motion control and effects team from London’s Arcadon, headed by Dennis Lowe.

Bavaria Studios, which was both the physical location where The NeverEnding Story was shot and co-produced, built us one of the largest blue screen stages now in use, over 30 feet by 100 feet, in addition to several smaller stages. They operate with high frequency input fluorescent lamps, and may be used with films rated up to ASA 100, lens apertures to f/11, and at all camera speeds.

Depth-of-field is a constant problem with bluescreen techniques. The complete foreground field must be sharply focused in order to get sharply focused masks. This requires shooting at the smallest possible aperture, especially with models in closeup. In this regard, the larger VistaVision format meant even further complications.

We also had a problem with Eastman’s high speed stocks, 5293 and 5294. They are not suitable for bluescreen work because of their lower blue sensitivity, although in all other aspects they would have been the ideal solution. We chose, then, to work with 5247, with carefully selected emulsion stocks, and with lots and lots of light. Of course, with a 100 foot bluescreen, and a very large set, we reached our lighting limits very quickly. We alternately faced two problems: not enough available lighting (we used an enormous number of lights), or the often incredible heat. During one sequence, we had a very expensive Ivory Tower model, built through much labor, simply melt before our eyes during one take. For all non-effects work, though, we did use 5293 and to the great delight of our team and of the Technovision “anamorphotes” — we could actually shoot at f/5.6!

Lighting provided some interesting problems. We all love to invent grand moods and atmospheres with lighting, especially when we have the luxury of a big set. But our sets were huge; we were edge to edge. We had to light a very big space, and still have room for setups and to be able to shoot at a variety of angles. We often were faced with the problems of creating a certain mood with hundreds of studio lamps, most close by the frame, to give the effect of one great light source, but one with a hazy atmospheric depth. Other times the large bluescreen was integrated into the set where it had to remain completely dark. We also, at many junctures, had to match the lighting on our very large sets to the lighting used on many specific models and miniature sets. Here, imagination was often struck by the cruel realities of modern production techniques.

For instance, in the “Swamps of Sadness,” we were faced with a relatively uncomplicated, although bizzare, swamp set. We illuminated it with about 120 Spacelights (similar to setups by John Alcott [BSC] on Greystoke), to suggest diffuse skylight. We created a misty atmosphere made of smoke, steam and dry ice, to a consistency that just hinted of the textures of the painted background — all to impart a feeling of endless depth.

Our problem: maintain this atmosphere at the same consistency over many weeks, in the cold studio as well as in full heat, and under all lighting setups. Our massive lighting was no help. But also, consider what mist looks like. How do you objectively measure it, day by day, to get that consistency? This consistency cannot be measured, and feelings, we found out, are often deceptive.

Another interesting problem, not photographic, but one that I had to deal with regardless: We had a horse, a very well trained horse that was scheduled to sink into a mud pool, standing of course upon a hydraulic platform. We had to shoot the descending horse at the point when we felt the mist was at the right consistency, the right mood, under the right lighting. From second to second the atmosphere changed. At any rate, seeing the film will describe our success or failure in meeting these problems.

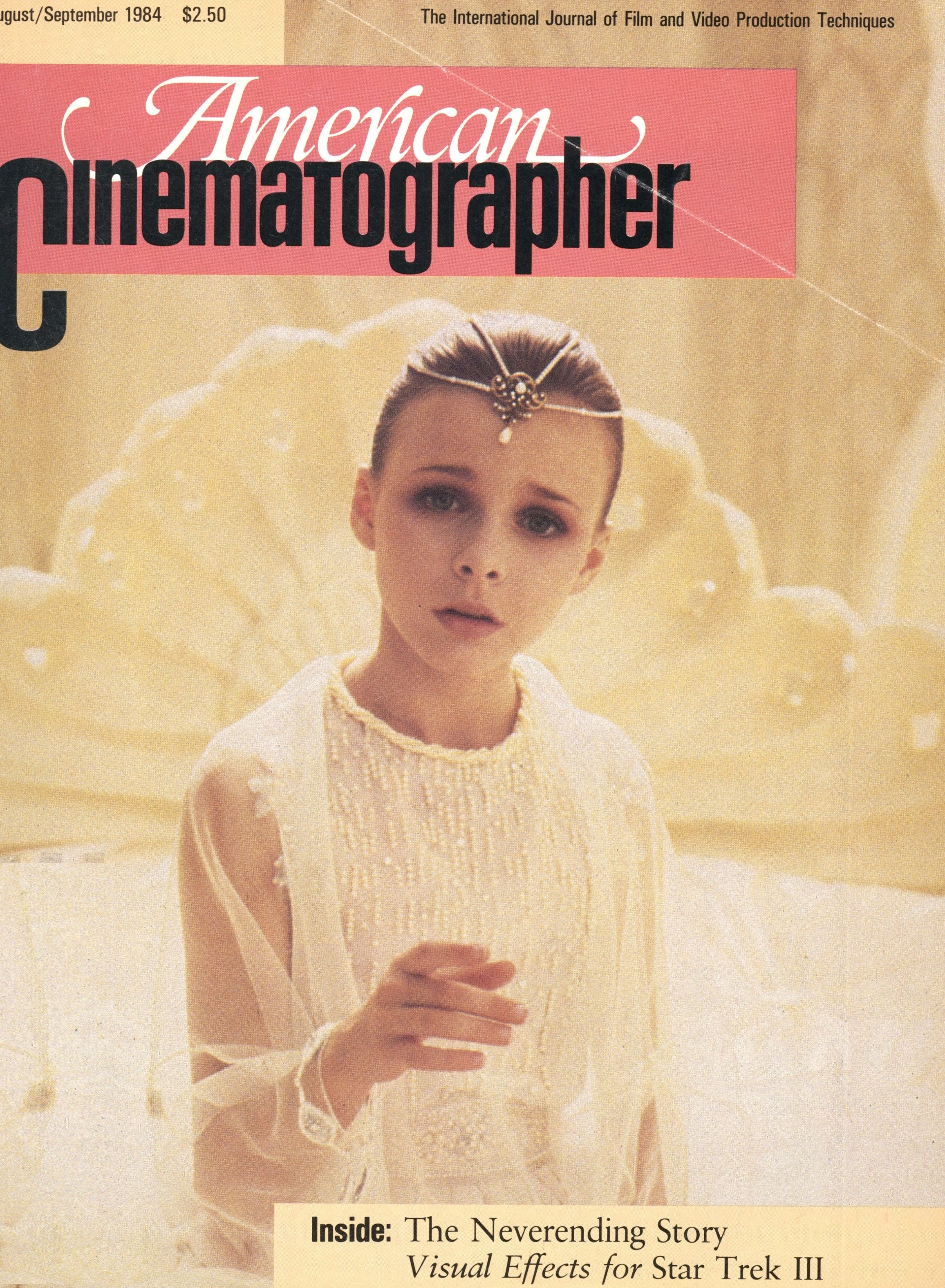

Only in the smaller setups were there no surprises of this kind. Scenes in the fire-colored kitchen of Urgl and Engywook, two witch-like gnomes living in a cave, we lighted with inkies only. Or the closing scene in the Ivory Tower, with the Empress; here, extremely soft light, with stockings in front of the lens, and a pronounced over-exposure, resulted in an unreal atmosphere, one indicating the mark of near-death needed for the shot. In order to get proper looking light beams, in a shot seen near the end of the film, inside one of our Ruins sets, we used high intensity aircraft landing lights to get the required punch.

The nocturnal, moonlit Haule-Wood was a typical blue screen set designed for this film, characterized by greatly varying dimensional proportions. Here, the Rock-Biter, a gigantic monster, meets the “Teeny-Weeny,” with his racing snail. In Bavaria’s Stage No. 4/5, the foreground scenery, framed by giant trees, was built in front of our huge blue screen, with all the small creatures performing in the foreground. The set’s background was built into another stage behind, with all the foreground scenery reduced to normal human proportions. Here, the Rock-Biter was photographed, human sized, chewing on boulders, with rock “crumbs” continuously dropping from its mouth. These crumbs were designed to fall upon the small creatures below as heavy rocks. To give the illusion of a creature of great height, we knew that the rocks must seem to take along time to hit the ground. To achieve the effect, we shot the Rock-Biter with one of our Arri 3s at speeds between 75 and 100 fps. This, however, made it necessary for the creature to “speak” at three to four times faster than normal, so as to appear normal at projection speed, and of course, sync with the voice-over. It was a major miracle of this picture that the six operators who produced the Rock-Biter’s face and mouth movements managed to maintain this accelerated speed with only slight monitor contact.

Bluescreen, more normally, also requires actors to “interact” with partners that may or may not actually be there — or even exist. We relied heavily on video monitors to make this process more efficient. Previously produced rushes were transferred to tape and combined in the viewfinder image by chromakey. In this way, we could control the composite and the eyelines before shooting. This raw composite was re-recorded onto film, and used during the editing for reference, until the final film composite came back from ILM, usually weeks later. All our Arris, and the VistaVision cameras, were equipped with video.

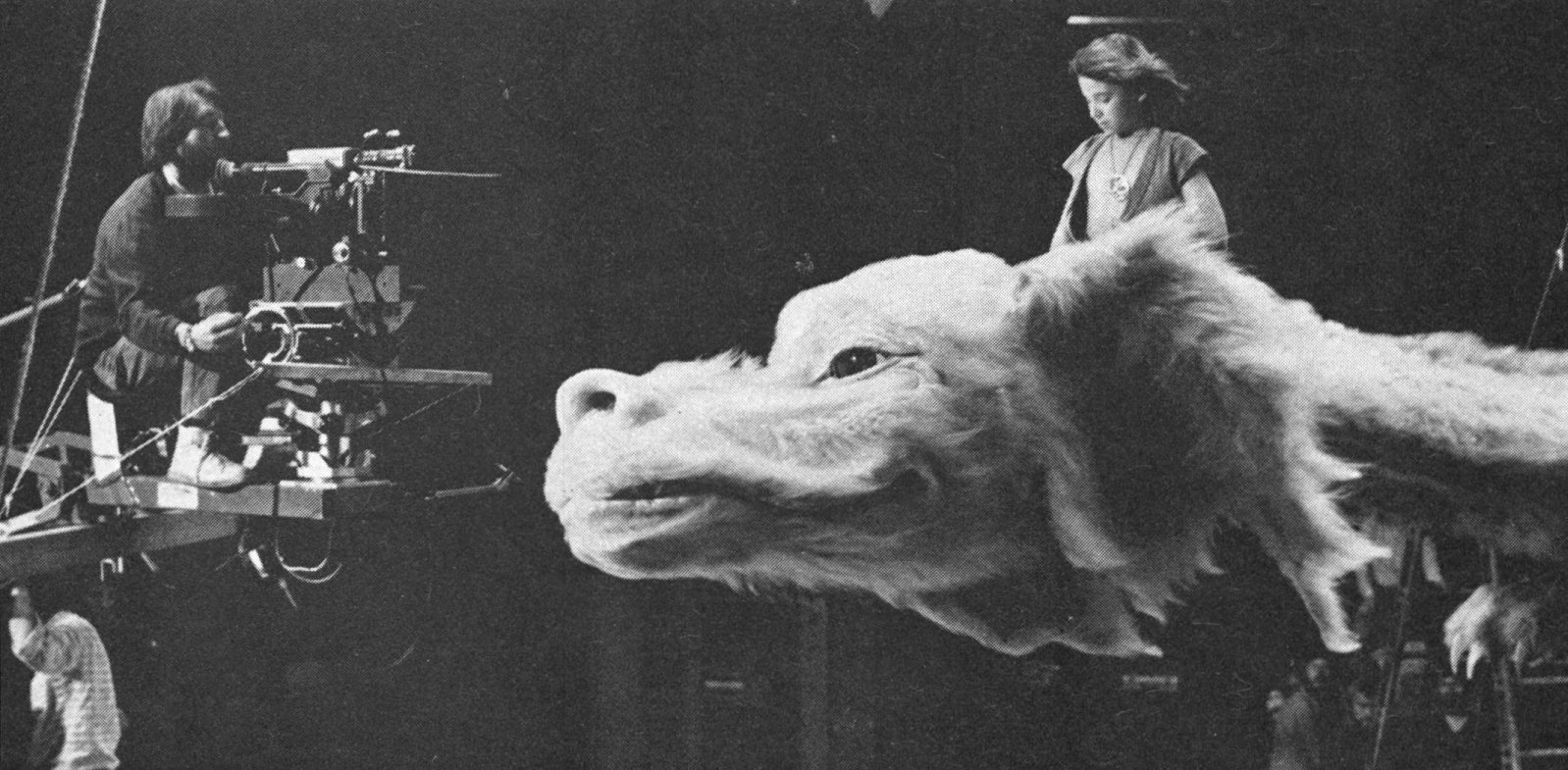

The flights of Atreyu on Falkor also benefited from this technique. The head of Falkor, the dragon, and its neck were animated by 18 operators, each controlling four different movements. As the dragon could not fly, we flew the VistaVision camera. We mounted the camera on our Tulip crane, and it could be rotated around its optical axis. Control cables kept the camera straight during swivel motions of the crane. We could move the camera in vertical, horizontal and axial directions, enabling us to simulate all the flight motions of the dragon, even those of a dragon caught in gale force winds. We controlled all dragon and camera movements visually through monitors, and even our actors were able to react perfectly on cue. Our setup was so versatile, that my operator, Peter Maiwald, got sea sick — we found this feature, of course, of limited professional use!

Our video monitors were of great value to us. For instance, we had a scene where the non-entity, “Nothing,” with an enormous suction effect, pulls everything away with itself. Atreju, clinging to a tree, is left hanging horizontally across the screen while everything else is sucked away, even mighty walls. For this shot the whole set, excluding cameras (3), lights and wind machines, was slowly tilted to a vertical position. All camera settings were checked through our Arri video systems, and the director was able to make immediate decisions regarding framing, placement and the necessity for re-takes.

The last shot in the picture is one I’ll long remember. A bit of sky, a few corners of houses and nothing else. The dragon enters and slowly disappears from the sky. Alas, at the last moment, the dragon was removed from the end, and all that remained for the audience to see was a plate shot - one that I didn’t shoot. C’est la vie, c’est la movie!

Nearing the end of the long shoot, I could only agree with Wolfgang Petersen, who said that, arriving at the locations for exterior shots in Vancouver, shots documenting Bastian’s home, his school, his home street, we were breathing freely again. Finally, we had real human beings facing the cameras again, with normal setups and normal shooting. No creatures, no strange cameras, just moving our camera through real streets — the world was in order again.”

Forty years later, The NeverEnding Story is beloved as a cult classic, particularly by those who grew up in the 1980s. It spawned two film sequels (in 1990 and 1994), an animated series (1996) on HBO, and a 13-episode television show in 2001.

At the time of its production, it was the most most expensive film ever produced in Germany, surpassing, ironically, Das Boot.

Vacano would go on to shoot such imaginative sci-fi films as RoboCop, Total Recall and Starship Troopers, and was also invited to become a member of the ASC.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.