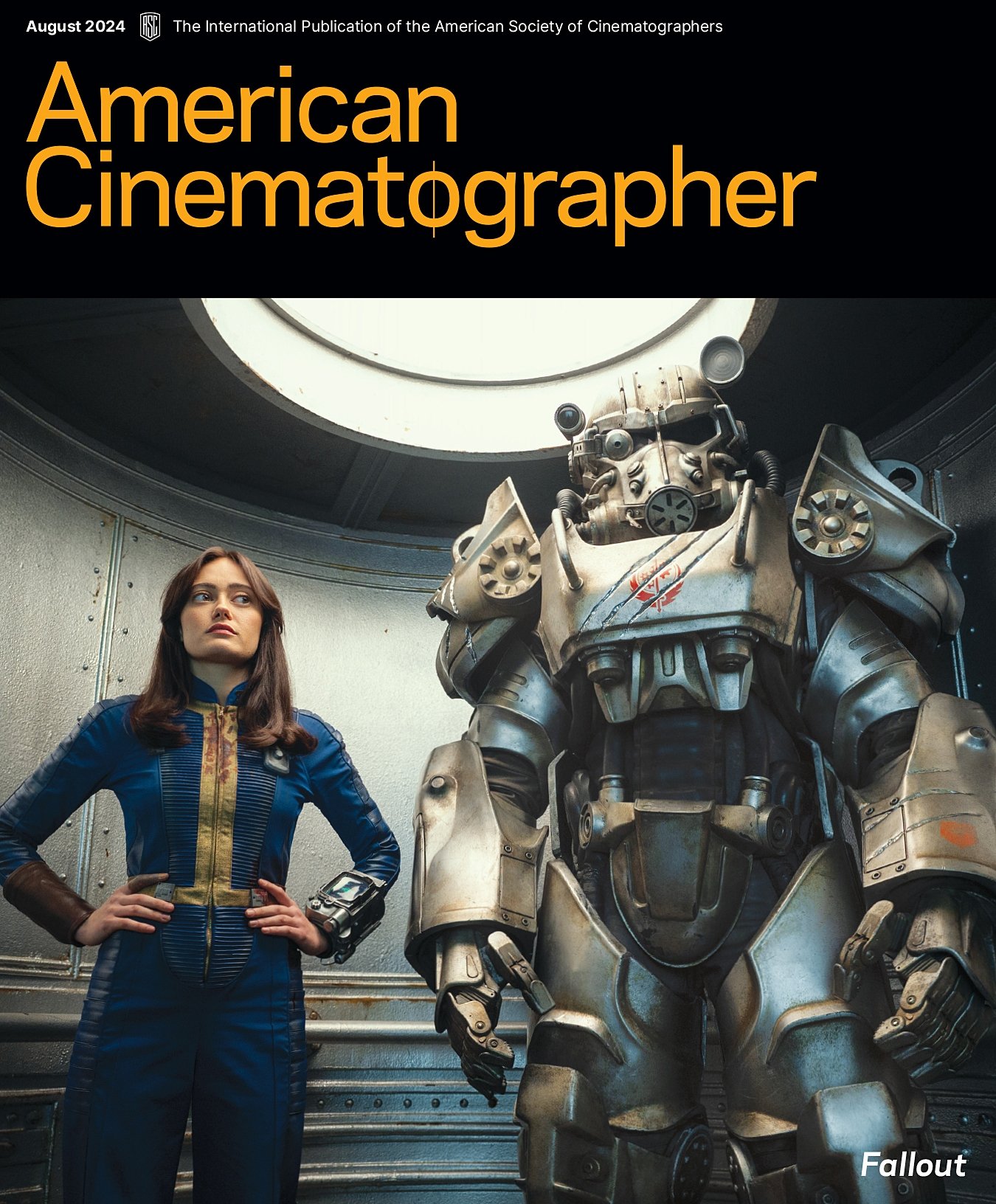

Twice The Horror: The Texas Chain Saw Massacre

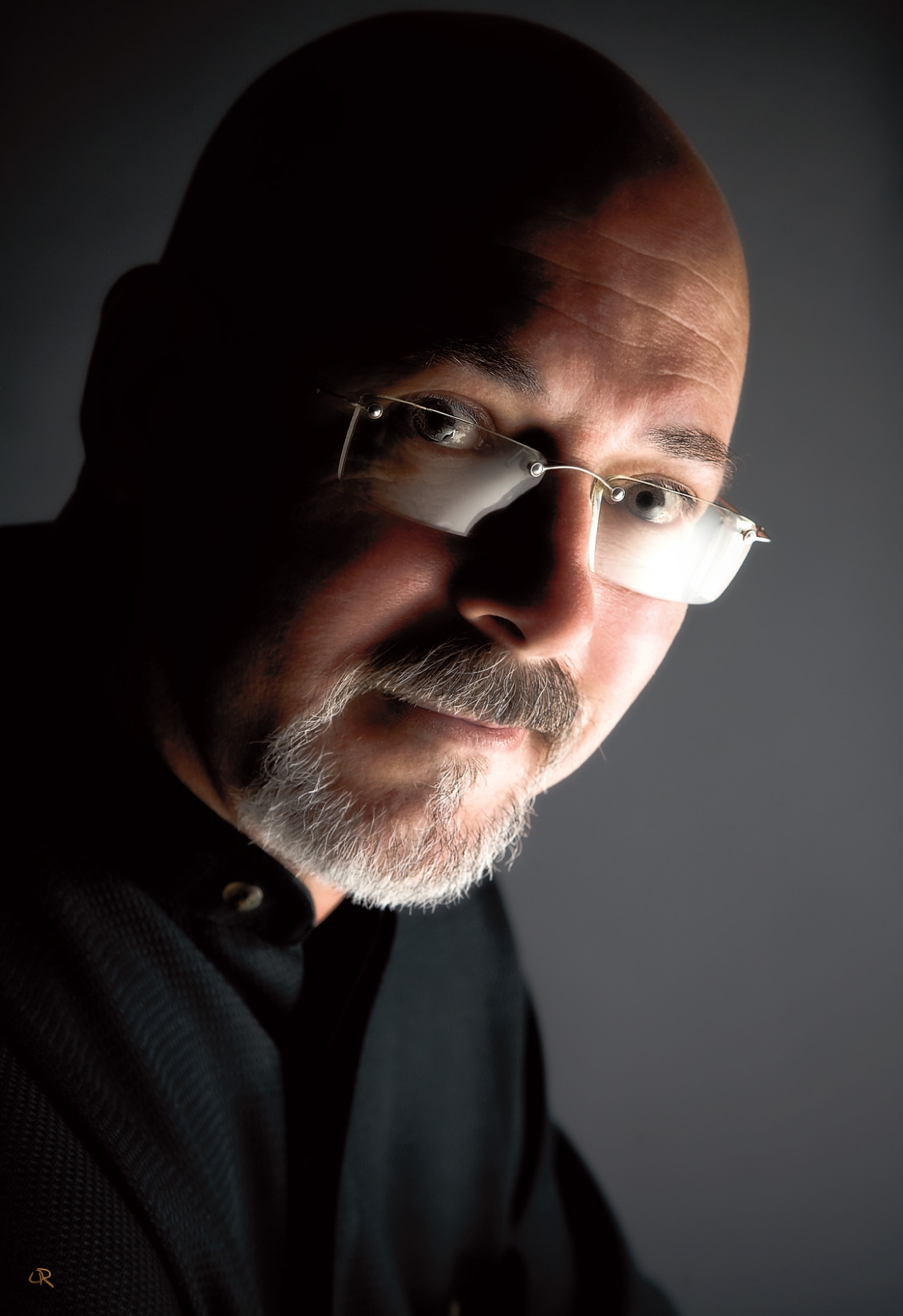

Daniel Pearl, ASC looks back at shooting both Tobe Hooper’s iconic 1974 horror classic and Marcus Nispel’s 2003 remake.

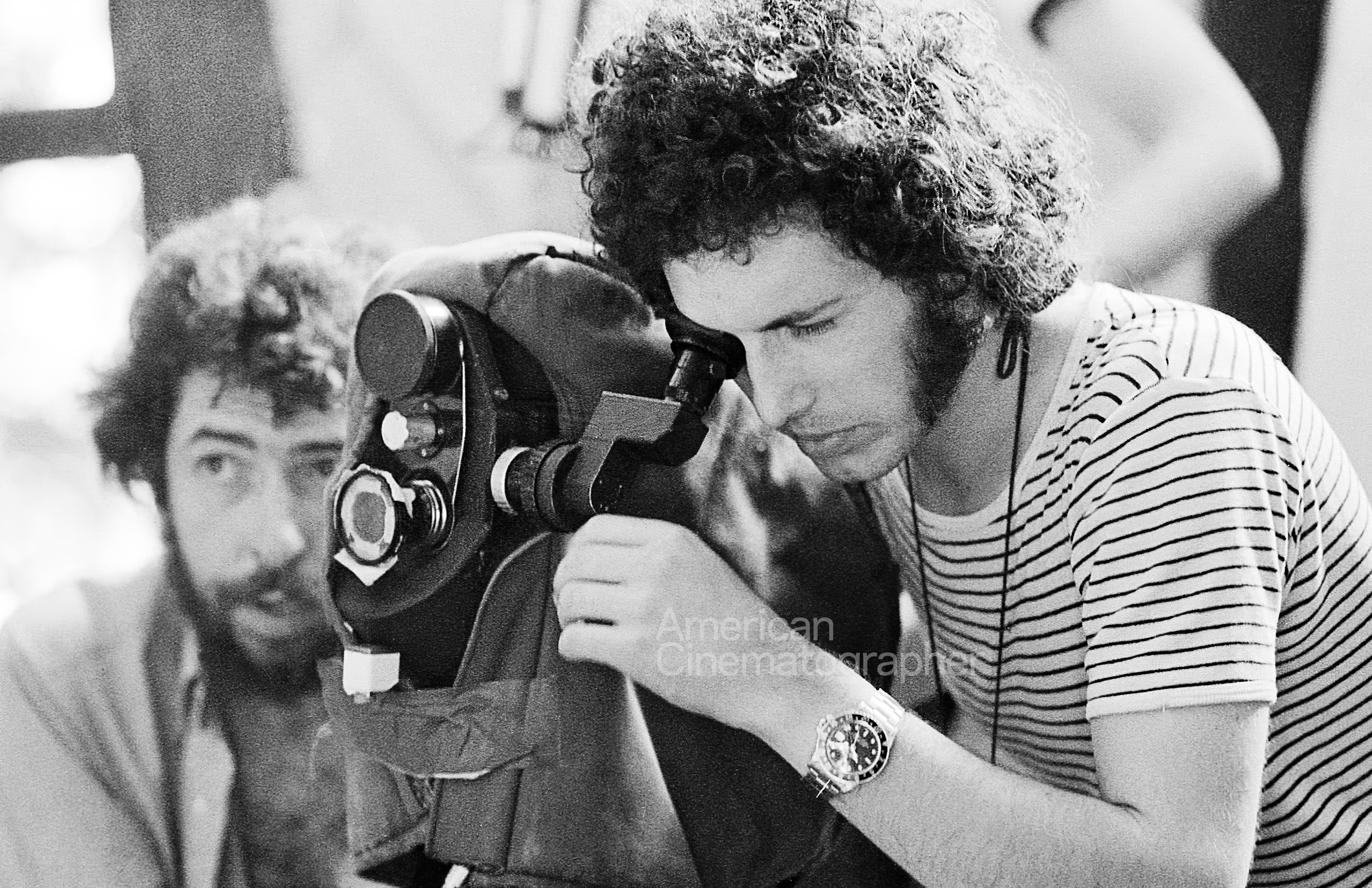

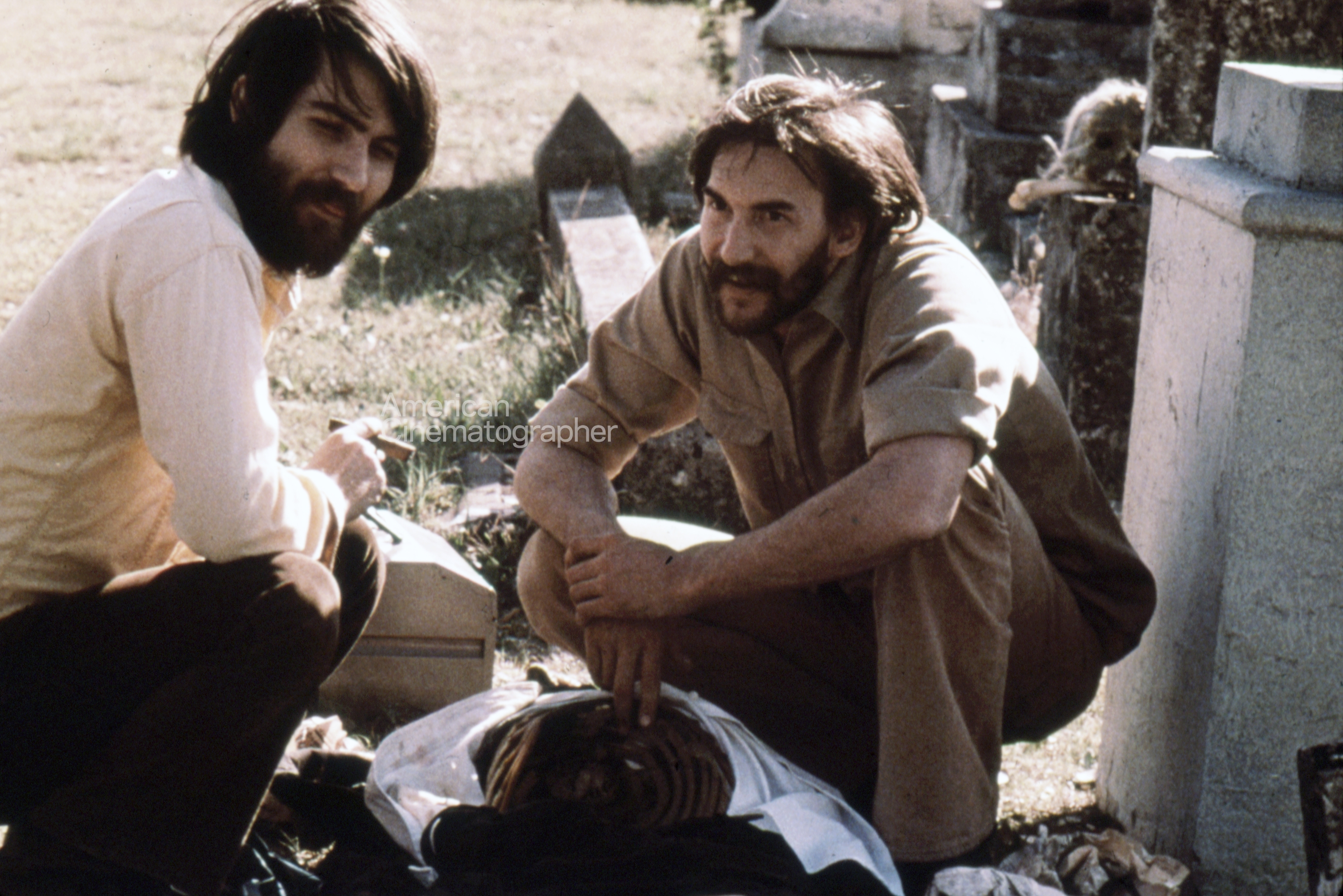

When Daniel Pearl, ASC set foot on the set of co-writer and director Tobe Hooper’s original The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, he was just 23 years old. “It’s a pretty outrageous number by today’s standards,” he says now, “but in 1973, it was ridiculously young!”

A scrappy film made on an estimated $80,000 budget, Texas Chain Saw would go on to become a horror classic and launch a franchise — as well as Pearl’s career. Today, 50 years after its release, the 1974 movie stands alongside such titles as The Exorcist and The Shining as one of the scariest films of all time.

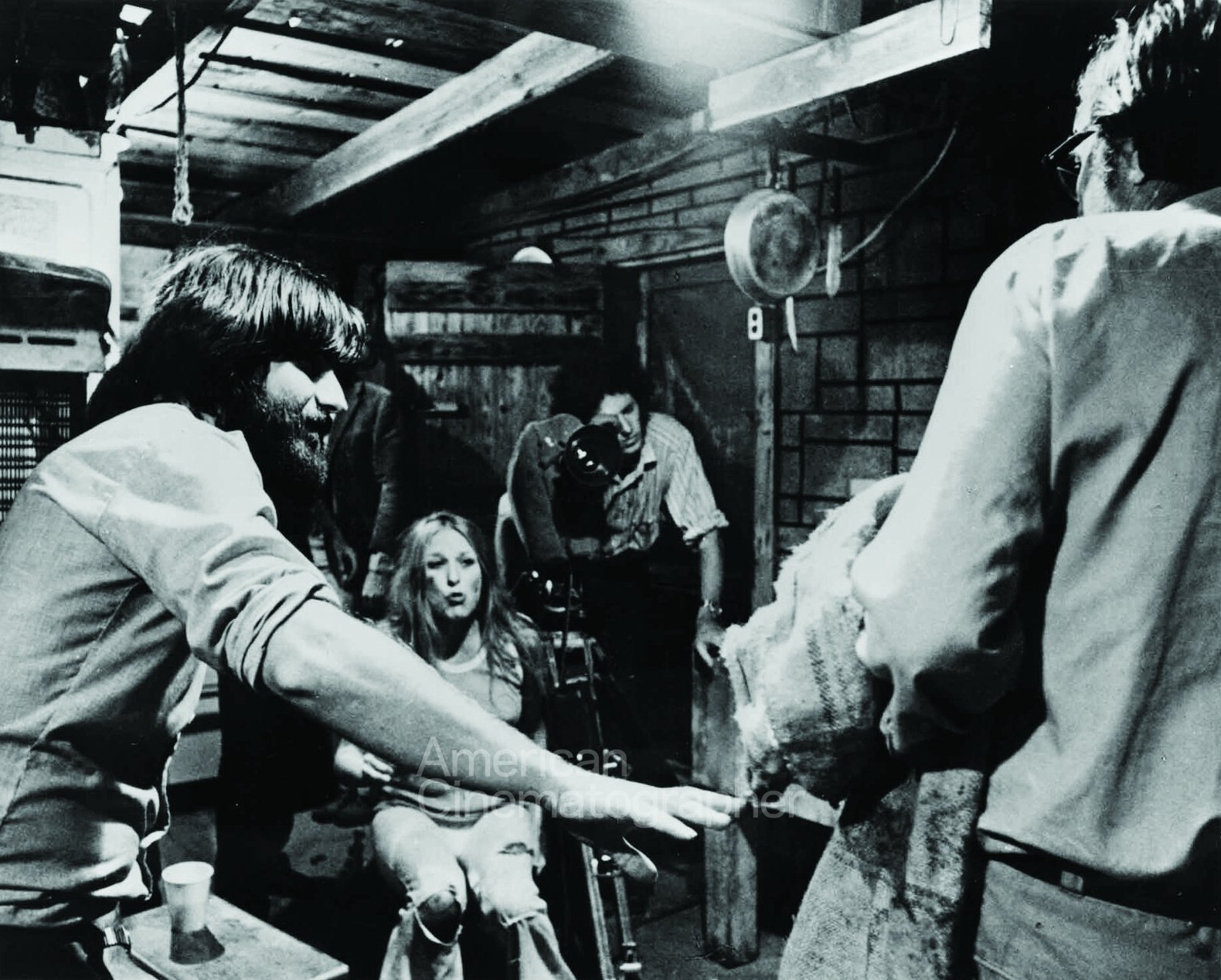

Pearl recalls that Hooper noticed his work while interviewing editors for Texas Chain Saw. The shot choices in a Texas Department of Public Safety PSA caught his eye, and it had been shot by Pearl, who was working on several such projects for the department. The one Hooper saw depicted a drug bust. “It was very kinetic, combat-style, and very sketchily lit with just a few lights,” says Pearl. “Everybody’s jumping up and running, and the handheld is very fast, with swish pans, etc. Tobe, in the course of interviewing the editor, said, ‘Well, who shot that?’ And that’s how I got hired.”

“Today, 50 years later, I can tell you I still don’t know everything there is to know about lighting, but one of the great things about being a cinematographer is that you’re forever learning; you’re forever finding new tricks or figuring things out.”

— Daniel Pearl, ASC

Pearl had just earned a master’s degree in film from the University of Texas at Austin, and he’d worked as a teaching assistant during his studies. He turned to some of his best former students to populate the camera, grip and lighting departments on Texas Chain Saw. Creativity using minimal resources was key.

Pearl attributes much of the gritty, visceral feel of the film to production designer Robert A. Burns, who designed and built a set based on real photographs of the home of serial killer Ed Gein. (An enduring obsession for horror filmmakers, Gein was not only the inspiration for Texas Chain Saw’s Leatherface, but also Psycho’s Norman Bates and The Silence of the Lambs’ Buffalo Bill.)

The budget mandated shooting 16mm, but distribution required 35mm deliverables. To that end, Pearl devised a photochemical/optical workflow that would maximize his image quality. First, he would shoot on the finest-grain tungsten-balanced 16mm reversal film available, Eastman Ektachrome Commercial 7252, which had an ISO of 25. Also known as ECO, the stock was low-contrast and intended for duplication and printing use.

After the final edit (performed with a dupe print), the ECO 16mm camera original would be conformed as A/B rolls and printed to create a 35mm internegative, complete with all required optical effects. By shooting a positive stock instead of negative, Pearl could skip creating a 16mm interpositive, thereby reducing contrast build-up, color shift, dirt and other possible image artifacts.

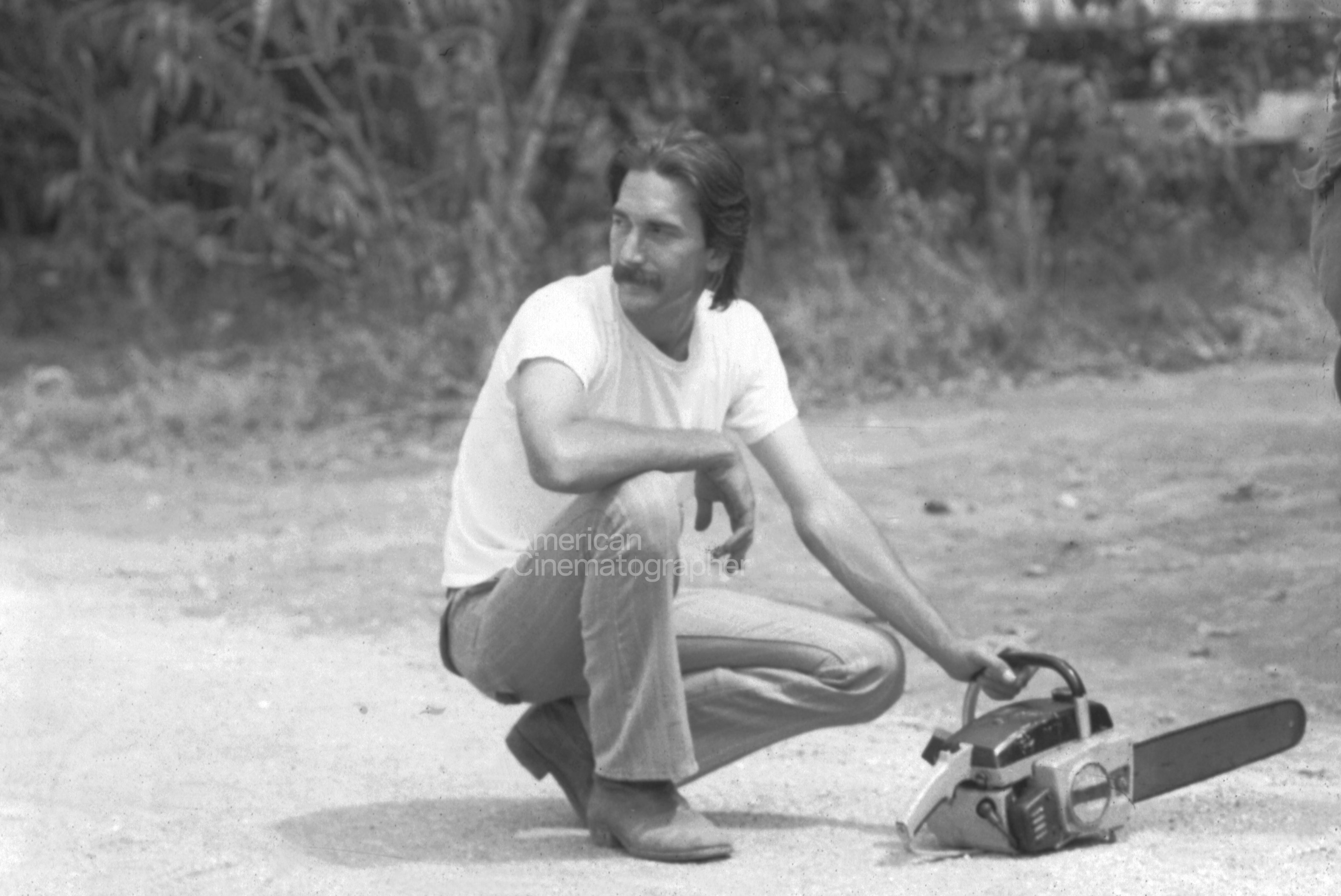

Shooting ISO 25 stock posed some challenges on the movie’s fairly numerous night exteriors, which included an extensive chase sequence. Pearl recalls, “I didn’t have big lights. HMIs didn’t exist. We certainly didn’t have a crew that could use arcs. I didn’t have a big lighting crew or a big lighting package. So, I had to work in a minimalist manner, which gave a bit of a documentary feeling.”

The night exteriors were also the reason Pearl originated on Ektachrome instead of Kodachrome. For daylight scenes, the harsh Texas sun would be more than enough to compensate for the necessary 85 filtration.

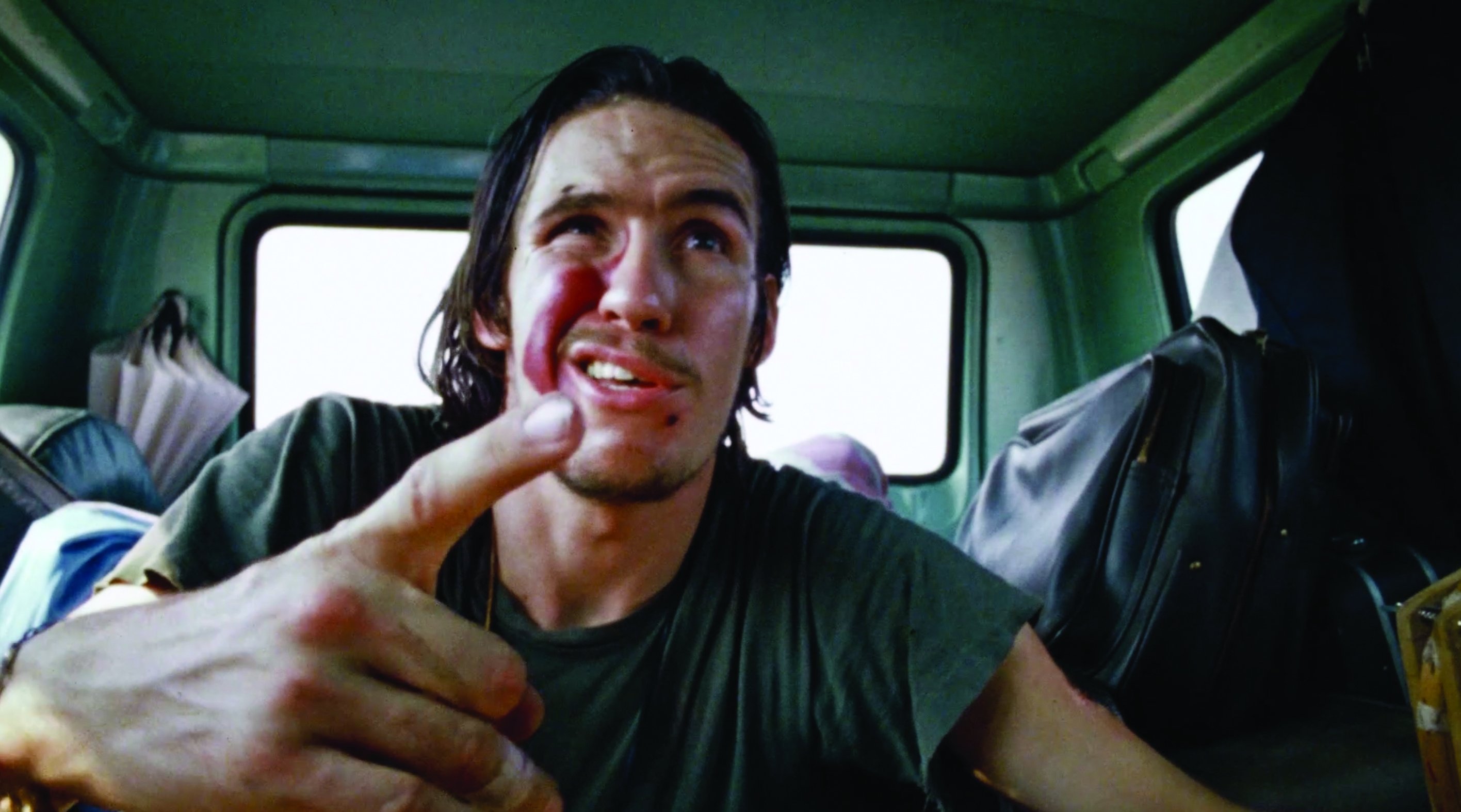

Seeking ways to give night exteriors texture and detail, Pearl found that working with particles in the air added to the frame. “I stepped out on the front porch for a cigarette in the midst of shooting the dinner scene. As I did, the caterer came driving up the dirt driveway. Following the caterer was another vehicle. When the caterer cleared my vision and went around the side of the house, the other car came through. The dust was stirred up, and I saw the dust in the car headlights and thought, ‘Oh, my God, this is incredible!’”

That moment inspired Pearl to ask actor Edwin Neal (portraying the Hitchhiker) to shuffle in the dirt when he is caught in the headlights of the sheriff’s car. “That’s where I learned about back-lighting smoke and playing with shafts of light, which is something that became a signature in my work,” the cinematographer says.

Pearl was as ingenious with shot design on Hooper’s film as he was with lighting. “We designed a lot of interesting moves with one platform dolly and 60 feet of track. We tried to keep shots moving with a point, not just gratuitously, but driving things home through tracking and bringing some new element into the frame, moving in on the actresses for emotion.”

With this concept in mind, Pearl devised the underslung dolly shot that became an iconic moment in the film: Pam (played by Teri McMinn), suddenly suspicious that her boyfriend is missing, stands from a seated position on a swing and walks toward the mysterious house he has entered, as the camera tracks with her.

“The idea was that we have a platform dolly that rides low on rails,” Pearl says. “If I lay down on that dolly, I can hang the camera off the front and hold it. I can be behind the swing on our 8mm Zeiss wide-angle lens. When [McMinn] stands up and goes to the house, Linn Scherwitz, our incredible dolly grip, can push me and glide under the swing and then follow her to the house at the end of our 60 feet of track. The house will start out small in the frame, and as we come closer, it will grow and grow.”

Looking back, Pearl is still proud of what he accomplished — and just as enthusiastic about his craft. “Today, 50 years later, I can tell you I still don’t know everything there is to know about lighting, but one of the great things about being a cinematographer is that you’re forever learning; you’re forever finding new tricks or figuring things out. It’s just a joy. It’s a great task to have, lighting, because it’s just so interesting, and you can create a mood so well with it.”

“I totally flipped the style on the remake, and I actually am very, very proud of how that film looks. Michael Bay, Marcus Nispel and I, along with a dozen other people, had been elevating the visual aesthetic of this audience through music videos. It was not the same audience that the original had.”

When Pearl signed onto director Marcus Nispel’s 2003 feature The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, having a film’s original cinematographer onboard to shoot the remake was virtually unprecedented in Hollywood — and remains nearly unheard of today. He notes, “The reason for that is that remakes are usually 20 to 30 years later. This only happened because I was so ridiculously young when I shot the original. When the remake came along, I was 52, and I was still shooting top music videos. I was still a young-thinking guy very much shooting for that demographic.”

Nispel and Pearl had had a long and fruitful collaboration prior to Chainsaw. “Marcus and I were totally of one mind compositionally and light-wise,” says Pearl. “I worked with him for 15 years or so. He was one of the top guys in commercials, and I shot with him for a long time, basically doing close to 200 days a year shooting commercials. So, he and I were very, very much in sync in terms of what we wanted things to look like.”

Chainsaw was Nispel’s first feature, and although he immediately wanted Pearl to shoot it, the production executives at Platinum Dunes wanted to interview other cinematographers as well. Pearl ended up getting the job after submitting a reel that included his music videos for Divinyls’ I Touch Myself, directed by Platinum Dunes founder Michael Bay; Meat Loaf’s I’d Do Anything for Love (But I Won’t Do That), also directed by Bay; and The Fugees’ Ready or Not, directed by Nispel. He also included a copy of the original Texas Chain Saw.

Pearl was cautious coming onto the remake. When he was asked if it would be gritty and grainy, he replied, “I’m not shooting it like the original. This will be for the MTV generation. Marcus knew I wouldn’t knock myself off. I would only do something I’d consider original. It had to be very different because otherwise, I don’t know why we’d remake the film.”

Considering the remake 20 years later, Pearl notes, “I totally flipped the style on the remake, and I actually am very, very proud of how that film looks. Michael Bay, Marcus Nispel and I, along with a dozen other people, had been elevating the visual aesthetic of this audience through music videos. It was not the same audience that the original had.”

Nispel wanted the film to look like “puke,” a request that led Pearl to research color. “American Cinematographer had an article that breaks down all sorts of photochemical lab processes that you can do to film in order to alter the look [“Soup du Jour,” AC Nov. ’98, written by future ASC member Christopher Probst, whom Pearl sponsored for membership]. In the end, what we came up with after reading about all these various lab techniques was to use bleach-bypass. With that, they skip the bleach part of the process of development that takes some of the extra silver out. The image becomes a little more crunchy. The blacks are blacker and the colors a little more subdued, especially the oranges and reds.”

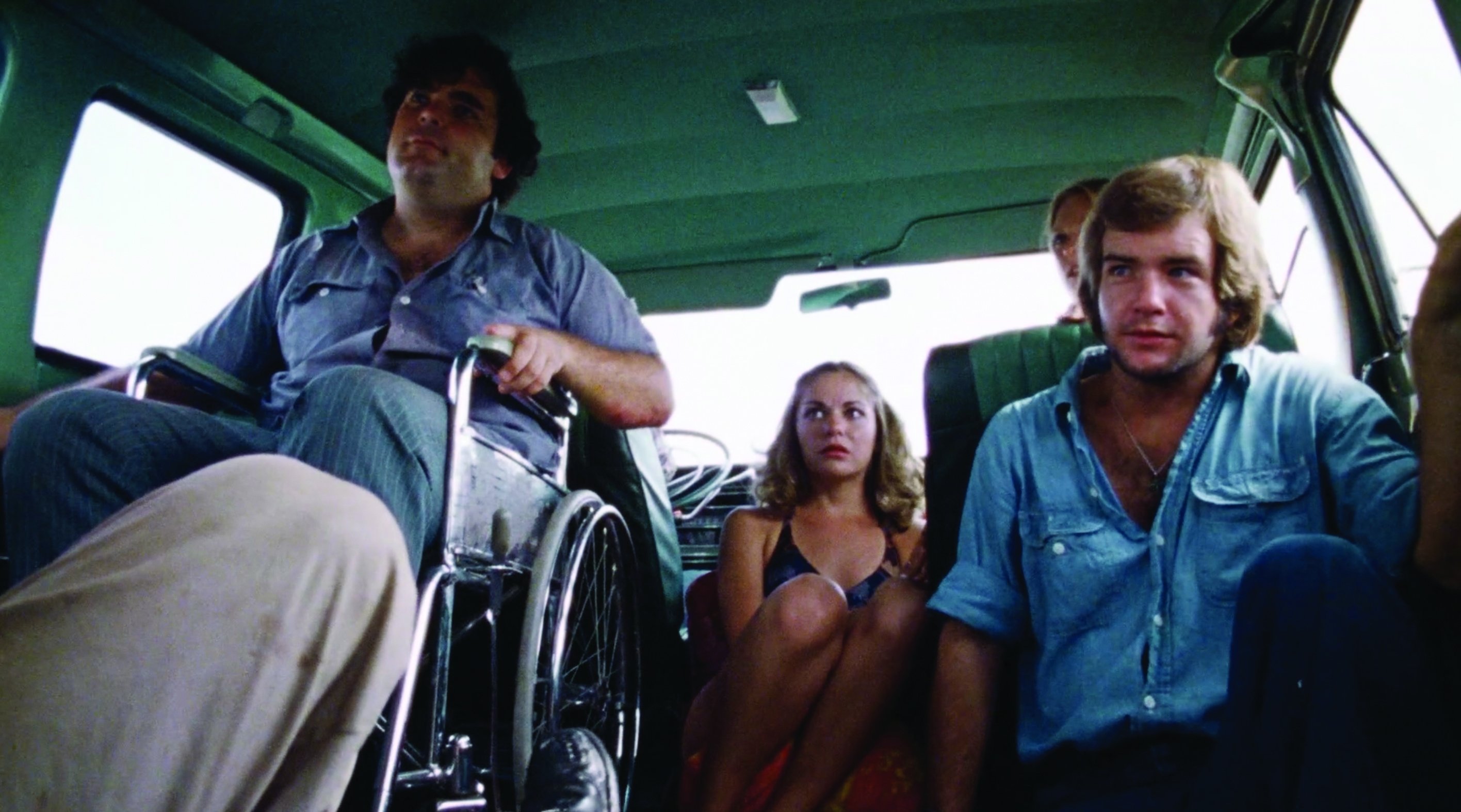

Pearl was excited to bring resources to the remake that he did not have on the original. For example, the opening scene that appears in both films shows the main characters driving through the desolate Texas landscape in their van. “For the remake, I lit it with HMIs. If you look at the original, I had no lights, so I was just shooting for the exposure that was inside the van. For a lot of shots, we could have just been standing still doing nothing because the windows are so blown out, you can’t tell we’re moving! I wanted to rectify that, and 29 years later, I was able to bring the light level of the van’s interior up to where the film could hold detail on the exteriors, so it doesn’t look so artificial. I used a lot of HMIs around the van. There’s a lot of power, a lot of 12K Fresnels. I had a key for everybody.”

Nispel and Pearl worked hard to make the film more contemporary while also paying homage to what they loved about the original. “Marcus was very aware of the under-the-swing shot from the original,” Pearl says. “He said the film had to have a signature shot like that. So, for the scene in which the hitchhiker girl shoots herself in the head while sitting in the back of the van, we designed a tracking shot that starts off at the front of the dashboard on a hula-girl figurine, [pulls] back through the length of the van — you see our five cast members — and through the head of the girl, and right on out through the bullet hole in the back window and out across a field to a very, very wide shot of the tiny van under this old tree.”

To execute the shot, Pearl had a slit cut in the roof of the van. By enlisting a Louma crane and removing the van’s rear window, the shot was possible with a probe lens. With nowhere to hide lights, the crew had a 15-minute window of opportunity to get the shot right before sunset, when the exposure in the van was matched to the outside world.

“We have the prop head already skewered over the probe lens and attached to the camera body so that when we start the move, the head is already over on the lens,” Pearl explains. “As we’re going backwards, right when we get to her body, there’s a prop man who grabs the head and Velcros it to the neck. As the camera goes back further, he lets [the head] slip and fall over backwards, and we carry on out the rear of the van. In post, visual effects replaced the ceiling of the van and the back window.” The complex shot took only two sunsets to get.

The 2003 remake was followed by other iterations of the Chainsaw story. Pearl remembers meeting with one of those cinematographers and giving this advice: “There are going to be haters. I shot the original and I shot the remake, and I got haters. Don’t let that affect your impression of your work.”

This article originally appeared in the August 2024 edition of AC. Subscribe here to get every issue delivered to your door.