Visions of Wonder — ASC Visual Effects Experts

Veteran Society members who hail from this always-evolving arena shine a light on the connective tissue between effects and “traditional” cinematography.

Photos from the AC Archives or courtesy of Bob Kohl, unless noted.

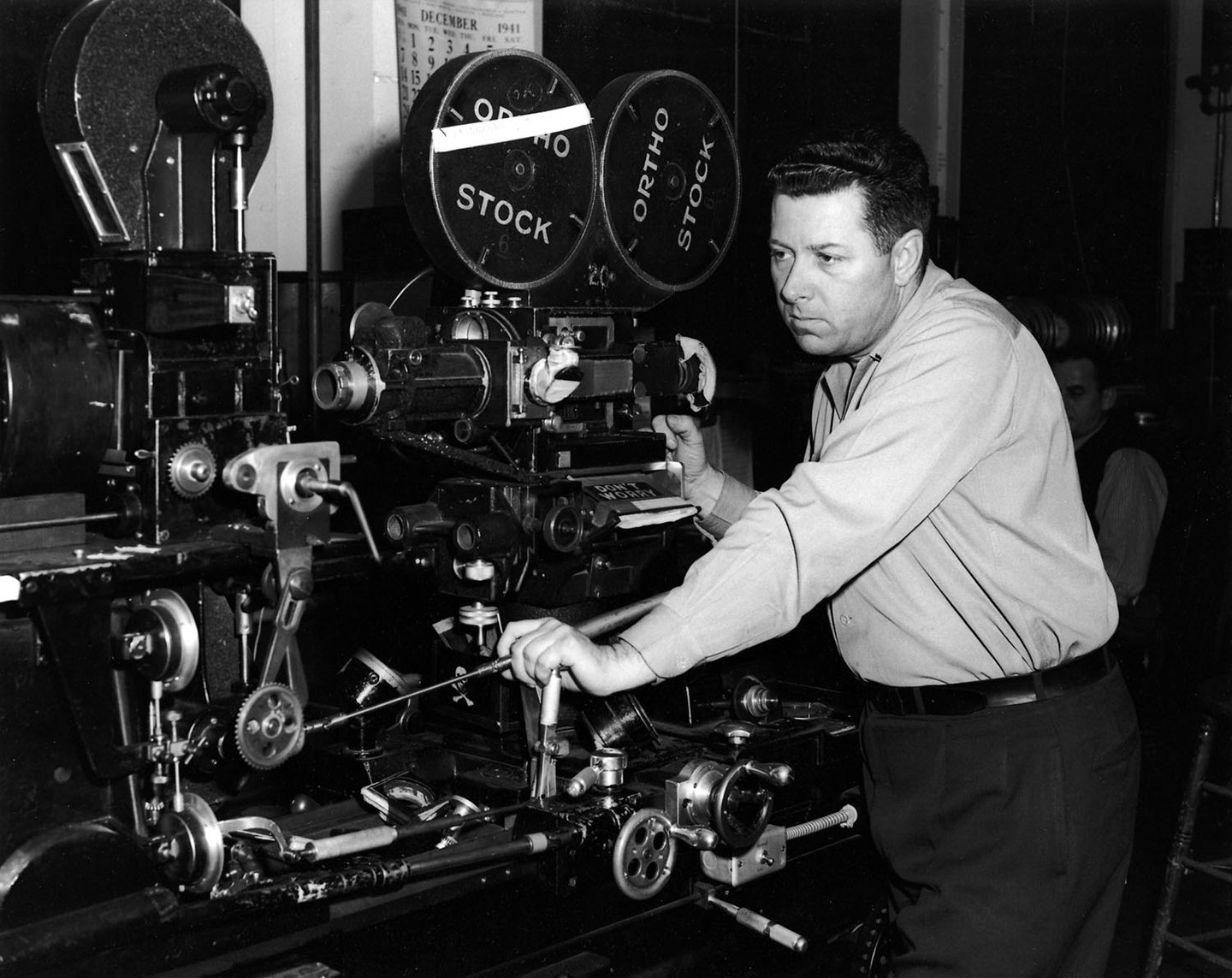

The art and science of “special photographic effects” — or, in the modern parlance, visual effects — has from the start been intertwined with that of cinematography. As effects wizard Linwood G. Dunn, ASC wrote in The ASC Treasury of Visual Effects, “In the earlier days such effects were made directly in the camera on the original negative during production. With the improvement in film raw stocks and processing, the quality of the duplicate negative progressed to the point where such effects, and much more sophisticated ones, could be made while copying the original negative and thus be produced with greater ease, less hazard and lower cost. This advancement led to much greater creativity due to the flexibility inherent in the freedom to complete the effects at a later date in the special laboratory, with full control at all times.

“As most of us who have spent many of our earlier years in this fascinating field well know, the solving of new problems is usually based on the accomplishment of some similar effect that has been done before,” Dunn continues. “Thus, the application of new technological developments, particularly computers, electronics, optics, chemistry… coupled with the creativity and enthusiasm of the new generation attracted to the special effects field… point to a future holding great promise for the seemingly unlimited need for the creative illusions found in so many of today’s important films.”

“The principles of cinematography are part of the inherent mechanics of visual effects.”

— Richard Edlund, ASC

Photochemical effects ripened to maturity with increasingly dexterous motion-control camera systems and mind-bogglingly complex applications of optical printers. New projects brought new breakthroughs, and early forays into computer-generated imagery paved the way for completely digital visual-effects workflows that have now opened the door to “virtual production” techniques — as evidenced in Avatar (AC Jan. ’10), The Jungle Book (AC May ’16) and the upcoming The Lion King — in which entire features are being “shot” without real-world cameras, locations or sets.

Throughout it all, effects and cinematography have had to walk hand in hand to ensure that a project will appear onscreen as a seamless whole, with its story set in a convincing world, however fantastical — or digitally fabricated — it might be. Indeed, in the digital era, it is increasingly difficult to tell where one discipline ends and the other begins.

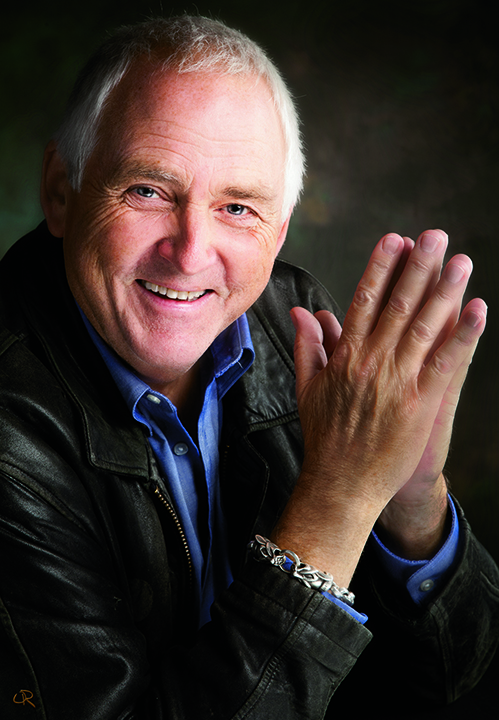

“The principles of cinematography are part of the inherent mechanics of visual effects,” Richard Edlund, ASC says. Fellow Society member Bruce Logan asserts that visual effects are “a branch of cinematography.” Anna Foerster, ASC adds that the disciplines have “a shared soul” — and Society member Sam Nicholson describes visual effects as “a digital darkroom” in which cinematographers can manipulate and combine images.

Mark Weingartner, ASC notes, “Visual-effects supervisors have always crafted images that were meant to be taken by the audience as straightforward live-action shots, so they have always had to be able to think like cinematographers. The field has evolved, and some of the specific knowledge VFX folks need to know has changed, but the underlying intentions and goals — to create photo-real effects that blend seamlessly with live-action photography — are the same.”

In honor of the ASC’s 100th anniversary and in recognition of the Society’s longstanding tradition of embracing effects pioneers, AC caught up with these and nine other active members — by no means an exhaustive list, but a sampling rich in experience and expertise — to discuss past, present and future intersections between cinematography and visual effects.

[Ed. Note: Credits listed parenthetically throughout this story indicate projects on which the speaker worked in a visual-effects capacity, not as a 1st-unit cinematographer.]

The Illusion of Reality

Richard Edlund, ASC (Star Wars [1977], Ghostbusters [1984], Angels in America [2003]): A lot of the great visual-effects supervisors came into the field out of cinematography. To do visual effects on film [and] be able to manipulate the images, you had to understand the photographic process. It was cantankerous and difficult; you had to know the process really well. That’s how I learned how to stage a scene, where to place a camera, how to light it — all of those things are common to cinematography and successful visual effects.

Mat Beck, ASC (True Lies [1994], Galaxy Quest [1999], Laundromat [2019]): To me, visual effects are ongoing research into how to create reality in the human visual system and, in turn, stimulate the emotional life behind it. In that sense, it’s not so different from the explorations of great painters, photographers and so on. At heart, great VFX, like great cinematography, is simply great storytelling. Change how we see, change how we feel.

Bruce Logan, ASC (Star Wars [1977], Firefox [1982], Batman Forever [1995]): My work has always been about artistic content and the motion-picture camera process. I think of myself primarily as an artist, a cinematographer and a problem-solver. Those three aspects combined are the essence of visual effects.

“For me, visual effects is all about cinematography.”

— John Dykstra, ASC

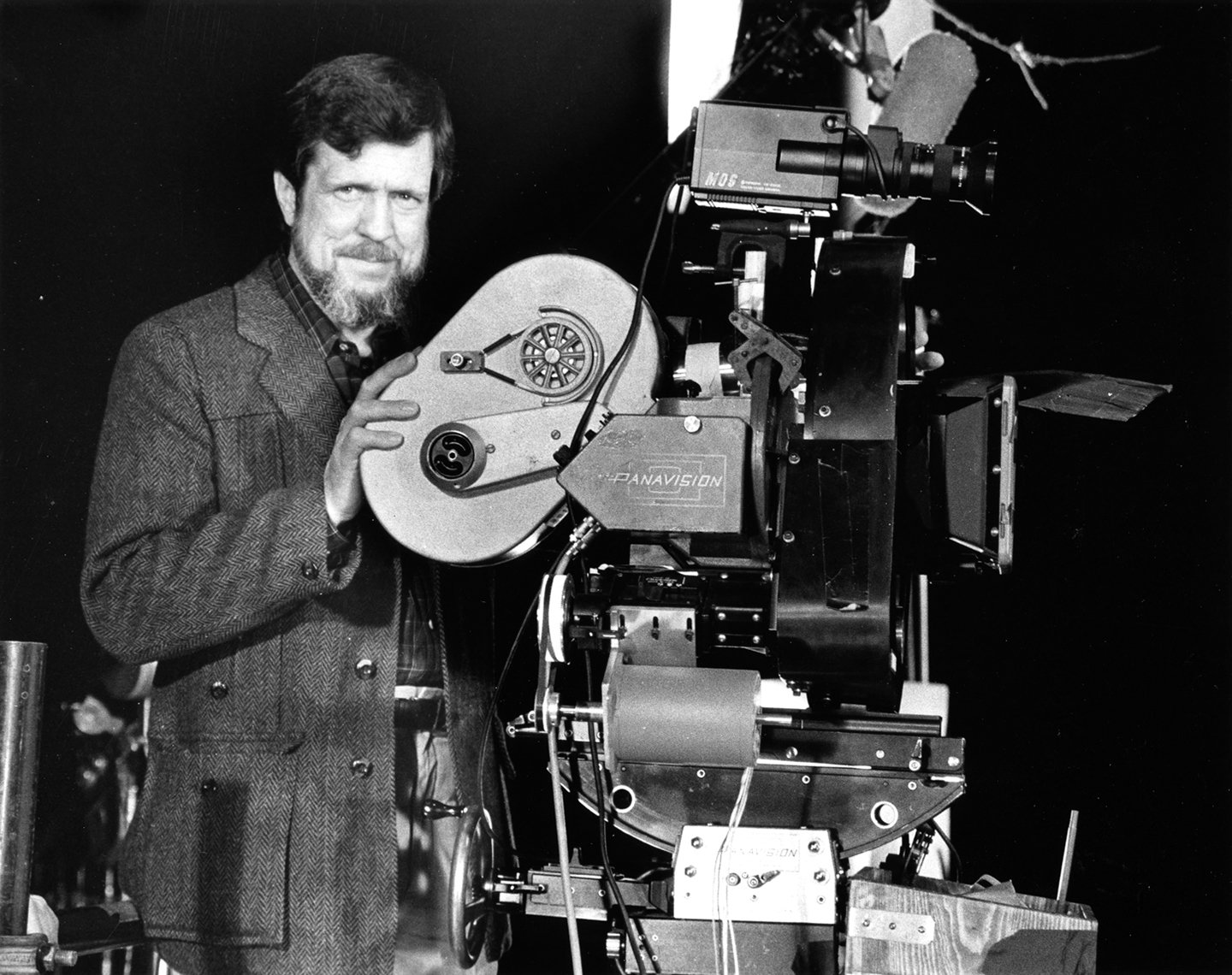

John Dykstra, ASC (Star Wars [1977], Spider-Man 2 [2004], Once Upon a Time in Hollywood [2019]): I started in photography looking at the pieces that made up an image. That’s why I was predisposed to doing visual effects — by definition, visual effects are two or more images captured at separate times and then combined to look as though they were captured in a single event. For me, visual effects is all about cinematography.

Sam Nicholson, ASC (Ghostbusters II [1989], 2000 AD [2000], The Walking Dead [pilot episode, 2010]): I consider myself a cinematographer first and foremost, and as a cinematographer, the camera is my primary tool of choice for capturing reality — and then trying to translate and combine [that reality] into all sorts of different things.

David Stump, ASC (Bill & Ted’s Bogus Journey [1991], X-Men [2000], American Gods [2017]): I think craftsmanship is frequently informed by the tools we use, and I have always been equally comfortable with computers and cameras. When you are a director of photography doing visual effects, you tend to want to get things in-camera, and when you are a CG artist, you tend to want to computer-generate things. There’s an advantage to combining the two. My camera background has given me an ability to synthesize [the two approaches] and know how to make a shot that fits into a movie.

Before the Revolution

Neil Krepela, ASC (The Empire Strikes Back [1980], E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial [1982], Cliffhanger [1993]): My time in [visual-effects company Industrial Light & Magic’s] matte department involved learning cinematography skills. For instance, you had to be incredibly precise with exposure and color timing in order to reproduce the live-action element so the matte painter could blend their work to it. We also shot additional miniatures or live-action scenes to add to the painting composite, in order to add life to the shot. Everything had to match the rest of the live action, so we were always looking at what the 1st-unit cinematographer was doing, and taking lots of notes.

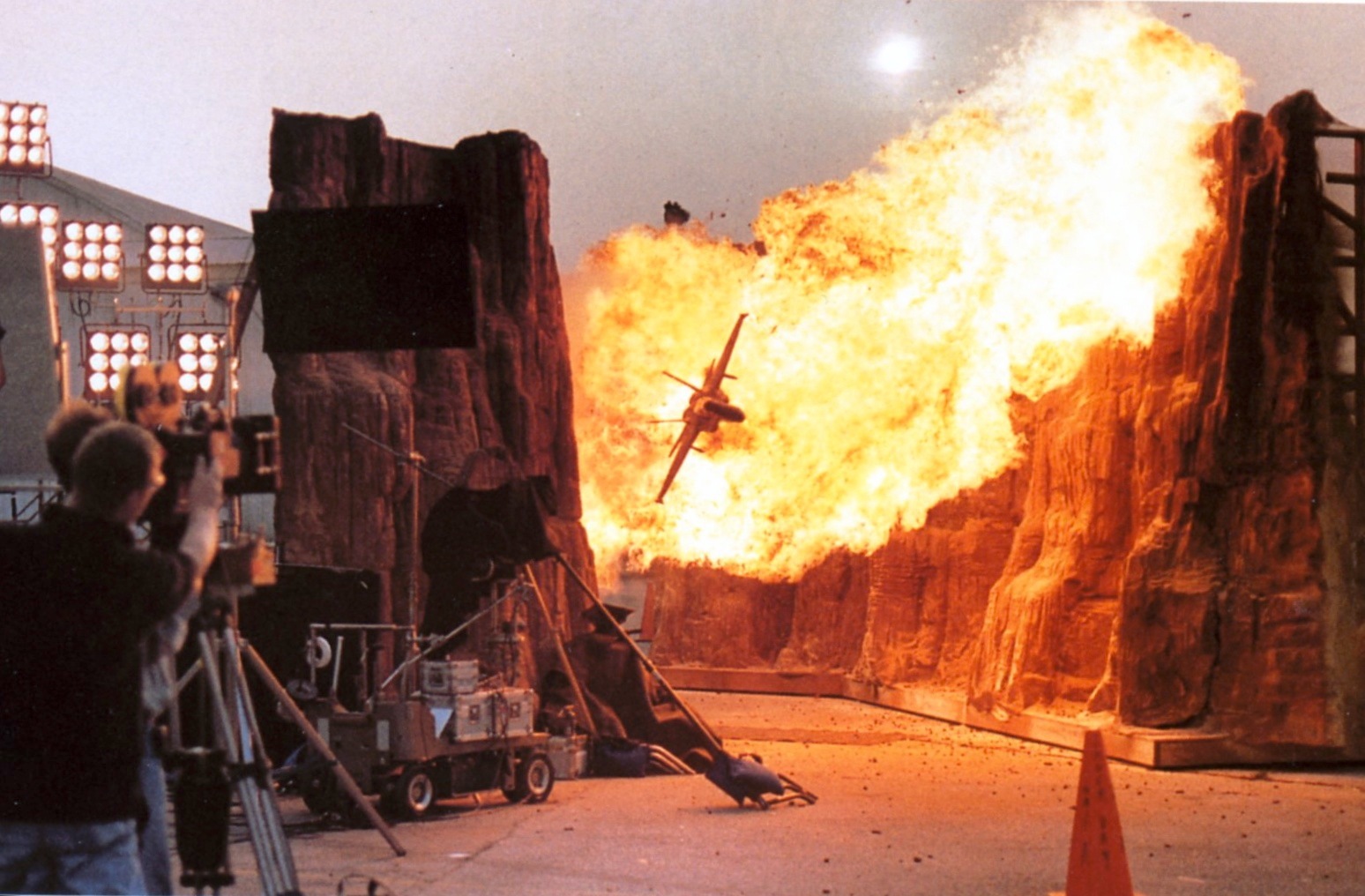

Anna Foerster, ASC (Independence Day [1996], Godzilla [1998], The Day After Tomorrow [2004]): Shooting miniatures with motion control or high-speed photography often required rather technical and by-the-numbers calculations. Translating frame rates, depth of field and camera moves to scale, [and] figuring out light levels and trigger sequences for miniature pyro shots, for example, involved some specialized knowledge that is used a lot less these days. It’s funny how much calculating those magic numbers was part of our craft.

Bill Taylor, ASC (Bruce Almighty [2003], Casanova [2005], Lawless [2012]): I learned how to do bluescreen shots [on an optical printer] largely by reading Ray Fielding articles in the SMPTE Journal, and then taking a Petro Vlahos night class at USC — he was the inventor of the modern bluescreen system as we know it. And so I eventually became an expert in doing bluescreen composites on the optical printer. I soon realized that one of the biggest problems with bluescreen composites at the time was the fact that they weren’t lit correctly. Foreground lighting wasn’t realistic — and secondly, the relative brightness of the bluescreen was usually seriously underexposed. So it was a matter of ‘self-defense’ to figure out, by following Petro’s lead, how to light realistically and expose bluescreen shots properly. I might have been the last cinematographer to carry shots all the way through from original photography to executing the composites.

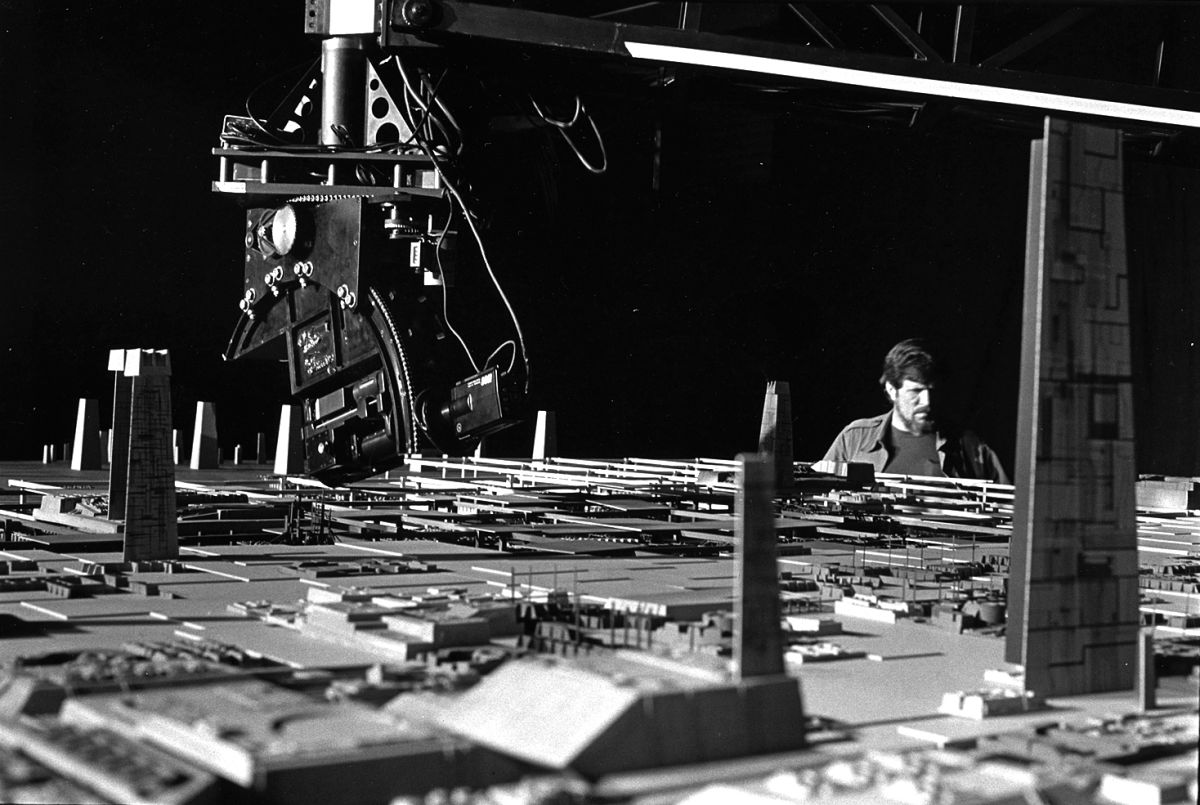

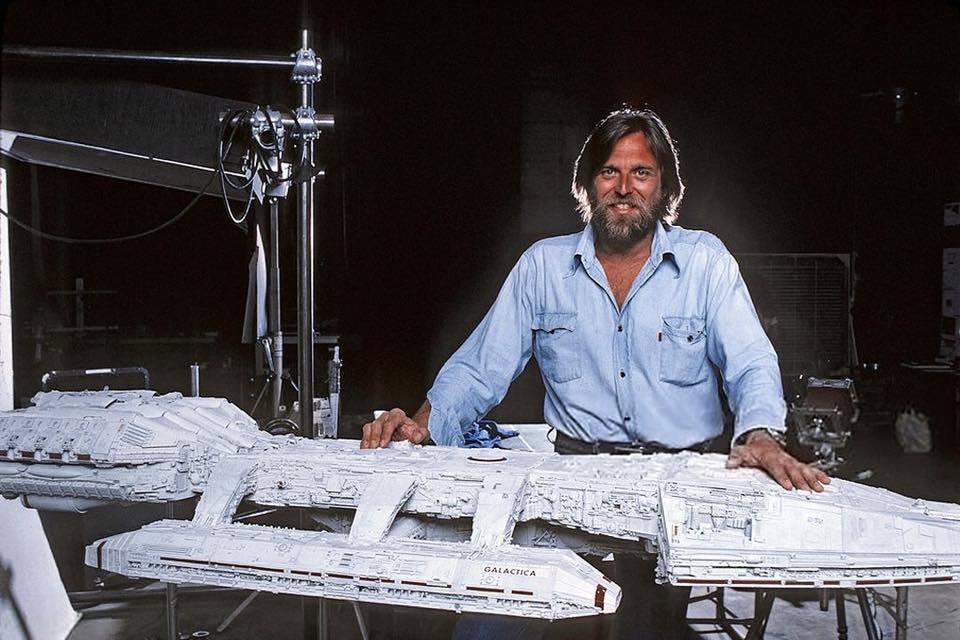

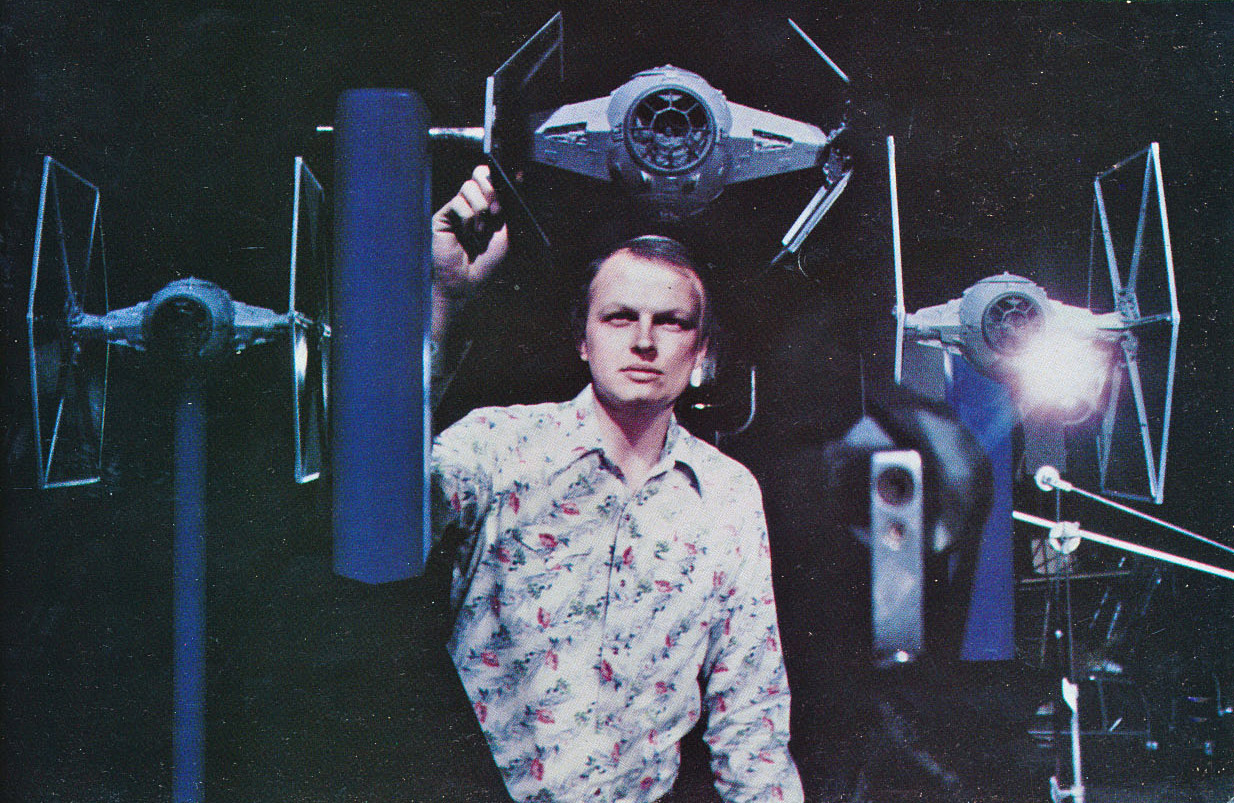

Dennis Muren, ASC (Star Wars [1977], The Abyss [1989], Jurassic Park [1993]): In 1975, when the original Star Wars started production, we effects cameramen were using equipment built in the ’20s and ’30s for live action. George Lucas wanted his Star Wars space battles to look like World War II aerial-combat footage: handheld and dynamic. So [special photographic effects supervisor] John Dykstra pushed for building a robotic and repeatable camera system — motion control — in order to fake incredible speeds by slow-speed shooting of multiple elements, and repeating the camera’s moves each time. He hired skilled people who embraced technology, engineering, electronics and optics. Revolution and confidence were in the air.

Dykstra: On Star Wars, we developed [the Dykstraflex]. Lens tilt was built into that camera to tailor the depth of field, and rather than stop-motion, our technique allowed us to do the same kind of positioning of the camera relative to the subject over time, but with the camera and the subject remaining in motion during the exposure. That resulted in the appropriate motion blur that is attendant to photographing subjects in the real world. [Ed. Note: The Dykstraflex was a seven-axis motion-control camera system, for which Dykstra, Alvah J. Miller and Jerry Jeffress were awarded an Academy Scientific and Engineering Award in 1978.]

Edlund: Painting ourselves into a corner and then having to invent our way out of it was an important part of visual effects and cinematography in that era. And then, when we did something that had not been done before, the innovation was put out there in the mainstream. People could see what we’d done, reverse-engineer it, and soon it became part of some new technique across the larger industry.

Logan: As director of photography on [1982’s] Tron, [which was among the first movies] to use CGI, I pulled heavily on my experience in animation and visual effects. In fact, every frame of film that I shot on that movie was duplicated onto Kodalith film, [and each] was used as an animation cel. Without intimate knowledge of the animation process, I wouldn’t have been able to optimize the live-action photography. Ultimately, I was creating a series of graphic images, so I had to completely eliminate motion blur and create infinite depth of field. Otherwise, the fine detail in the images would have disappeared.

Edlund: To do visual effects and manipulate the image on film, we had to understand the photographic process; we could not have done it without a background in cinematography. I built a lot of things back then — the first VistaVision spinning-mirror reflex camera for The Empire Strikes Back [1980], and optical printers. [Ed. Note: Edlund received Academy Scientific and Engineering Awards in 1982 and 1987 for these particular advancements.] We had a great team to work with for that stuff, and that is the great thing about moviemaking — it’s such a great collaborative medium.

New Films, New Advances

Krepela: On [1993’s] Cliffhanger, we took a motion-control camera system to the Italian Alps in the winter, and hung it vertically off a cliff-face. Not a small challenge, as this amounted to about 80 feet of track, weighing around a half ton, brought in by helicopter and secured by a crack rock-climbing team. This gave us the freedom to really move the camera during filming for what would normally be a locked-off shot. That experience was my inspiration for what would become the first computer-controlled, cable-supported camera system — the Dino-Cam, which was built by Walt Disney Studios when I supervised the movie Dinosaur.

Richard Yuricich, ASC (Blade Runner [1982], Event Horizon [1997], Mission: Impossible II [2000]): Our work on Under Siege 2: Dark Territory [1995] included a unique, though not much noticed, major breakthrough: the multicamera synchronous background plate system. It became apparent that 40 minutes or more of the movie would take place inside a moving train. I mentioned to the producers that in the future, a digital tracking system would allow us to actually go handheld on a stationary set surrounded by a large greenscreen, and to add moving exterior backgrounds. A producer put a finger in my face and said, ‘Do that!’ VFX-crew lighting gaffer Mark Weingartner designed the system for lighting the screens, and shot many of the plates, and then we did a successful proof-of-concept shot. [In the finished film, the technique] was used for more than 500 shots — 38 minutes of screen time.

Mark Weingartner, ASC (Event Horizon [1997], I Am Legend [2007], Dunkirk [2017]): On [2000’s] Mission: Impossible II, we pioneered the use of bracketed still photos tiled together to create HDRI textures. A few years later, we were using digital still-cameras on motion-control pan/tilt heads to create textures for the [nighttime] elevated-train scenes in [2005’s] Batman Begins.

Dykstra: When I [served as visual-effects supervisor on 1999’s] Stuart Little,we had a digital mouse that was 4 inches tall. This was my entrée into the world of digital characters. With macrophotography of a mouse in the foreground, the background goes soft-focus — this is where understanding the principles of cinematography became critical. We developed a lens tilt for our virtual camera to allow us to create synthetic depth of field so that our subject, the mouse, could be sharp, and we could be selective about what was sharp in the background, depending on where we put the lens tilt. That was adapted from our Star Wars cameras and still cameras before that.

Beck: For the final shot of The X Files: I Want to Believe [2008], the camera flies over a tropical forest and beach to find Mulder and Scully [David Duchovny and Gillian Anderson] in a rowboat in the ocean. That shot combined real-world aerial footage of jungle, beach and sea with CG ocean, digital matte paintings, and real actors in a boat in a pool in a parking lot. We used 3D previsualization to determine the basic camera move as well as the length of the oars that would fit in the tiny pool so [Duchovny] could have real water to row against to help his performance.

Stump: In the 1990s, I used to do a lot of motion-control work. [For] dollies, pan-and-tilt heads, focus motors, cranes — all the normal tools of filmmaking — I strapped encoders onto them and started recording their motion as 3D data, which I could use, at the time, to drive virtual sets in Maya or Softimage. Then in 2006, I did a movie for [director] Randal Kleiser called Red Riding Hood [AC April ’06], where we encoded every camera and piece of gear on the show, and used it to drive the motion of sets created in Maya. That kind of thing was a predecessor to being able to do a lot of the things we are doing now with virtual cinematography.

Digital Takes Hold

Weingartner: The move from photochemical to digital motion-picture photography has not really changed what I do, but it has affected aspects of how I do it. I describe a VFX DP’s job in the digital era as ‘harvesting grist for the digital mill.’ In this pursuit, I’ve designed and operated multicamera synchronous plate rigs for shooting background panoramas — and logged numerous hours shooting one-off plates meant to work for specific foreground camera angles, and innumerable single-camera tiled backgrounds with still and motion-picture cameras. VFX photography entails lots of exposure and frame-rate run-time calculations.

Taylor: Over my career, the most important development I saw was digital compositing — a Kodak invention. They had a [team] at Kodak Australia that invented digital compositing from the ground up with their Cineon system [which was unveiled in 1992]. The second revolution was the advent of digital photography that was co-equal in quality with film photography. After those two big revolutions, visual effects began to appear in films of every type and genre.

Robert Legato, ASC (Titanic [1997], Avatar [2009], The Jungle Book [2016]): At some point when CG first began to take hold, the cinematographer’s talents and contribution became a bit remote from the process. Certain things were, for a while, removed from their purview and put into an un-relatable ‘box.’ The only people who knew how to operate that box, or understand it, were purely CG technicians. Sadly they generally didn’t possess the same photographic knowledge or experience as a seasoned cinematographer, and of course that showed in the work. Naturally, over time, some became good at it, as they got some of their own experience as filmmakers, and became quite talented cinematographers in their own right.

“If you shoot on a set and you are a mediocre cinematographer, it will look like a set; if you are Gordon Willis [ASC], it looks like you are in a totally realistic location. The same is true of virtual cinematography.”

— Rob Legato, ASC

Muren: In 1984, for a CG character in Young Sherlock Holmes, I taught our small CG department [at ILM] about moving the camera, field of view, depth of field, variable shutters, matching lighting, shadows, glints and film grain — whatever I could think of to make each shot appear photographic and spontaneous. But to make our CG work vivid, composites were needed that perfectly matched the live-action plates, with no matte lines. It’s telling that it was under my direction and with my eyes — a cinematographer’s — that we finally solved the puzzle in-house and delivered 55 digitally composited, seamless shots for Terminator 2 [1991], on time and on budget. Just a few years later, everyone could get a perfect composite, making their work magnitudes better.

Yuricich: Today, an all-digital show has many departments, and most of those now have a digital supervisor. But I remember on Close Encounters of the Third Kind [AC, Jan. 1978], there were 18 or 19 directors of photography for additional scenes, reshoots, inserts [and] effects units. Also, in our Future General VFX facility [a Douglas Trumbull venture funded in part by Paramount], there was an average of eight VFX photographers working with various image-recording cameras — animation, insert, water-tank, matte-painting, rotoscope, miniatures, optical, and high-speed cameras. My job there was ‘director of photography’ for all cameras. The modern equivalent would be ‘digital supervisor.’

The Real-Time Realm

Legato: I’m fascinated with the idea of using a computer and VR to help replicate what real life is, allowing me to ‘shoot’ like it was a real scene on a real set. The tremendous amount of knowledge and experience you have as a cinematographer is now invaluable, because you are often asked to create a scene that looks like it’s been 100-percent naturally photographed even though not one stitch of it is real. The exciting part is, if you do your job well enough, it can now be indistinguishable from the real thing.

Logan: Even scenes with 100-percent CG imagery still use the basics of cinematography, even though the camera, lights and dolly are all virtual. I believe all the creative skills of the DP are required to create great CG images. And the skills required for managing a crew at 4 a.m. — lighting, cabling, placing wind and rain machines, and getting it done in the time allotted — that is a unique skill of the director of photography. On the other hand, getting 1,400 shots done in six months by multiple vendors also has challenges.

Nicholson: [Supervising major visual effects] today requires being a technology expert, but also being a good cinematographer — and being able to connect with other cinematographers, since now we are bringing complex imaging out of postproduction and putting it onto the set. That is why new methods like [virtual cinematography] are becoming a cinematographer’s dream. Instead of having somebody else screwing with your image in post, you are doing it live, and you can adjust.

Beck: New techniques allowing camera tracking, 3D CG rendering, and compositing — all on set in real time — are actually making complex shots simpler to shoot in an artist-driven, organic manner. At the same time, regular cinematography is seeing more VFX tricks in use to refine the original image — contrast, lighting, composition, etc. — in the DI.

“Cinematography is the language of cinema. People have come to understand the rapid succession of images in a very distinct, intuitive way. Whether such images are produced on set or in the computer is not as important as the need for them to be rooted in the principles of cinematography.”

— Neil Krepela, ASC

Nicholson: Visual effects are about finding ways to manipulate and combine images together. It was that way starting with optical printing and all the various in-camera tricks. Ironically, it is now going back in that direction, in the sense that visual effects are now moving out of the non-real-time realm and into the real-time realm, thanks to game engines for real-time rendering. For high-concept imaging, taking visual effects out of the postproduction, non-real-time realm — where it is separated from the cinematographer — and bringing it into the live-action realm, is exciting. I think that’s where everything is going. That puts a lot of power back into the cinematographer’s hands to achieve the look they want to achieve in-camera.

Logan: I believe there is a blurring of the lines today between cinematography and visual effects, with the advent of virtual photography to drive CG characters and environments. If it is done well, you really don’t know what you are looking at — the work of the cinematographer or the work of a digital artist.

Legato: You still have to photograph it well. If you shoot on a set and you are a mediocre cinematographer, it will look like a set; if you are Gordon Willis [ASC], it looks like you are in a totally realistic location. The same is true of virtual cinematography. It’s not good enough to know how to operate a computer — you have to be an artist, a cinematographer. You need to know where and how to aim a camera dramatically, when to move, when not to move, how to compose, what appropriate lens choice to make. Since the outcome appears to be the same, does it suspend disbelief and follow the same dramatic story requirements as any other real-world shot would? Our work now needs to be judged on these merits alone and can no longer rest on the laurels of technical achievement. Those days are over, and the art form is all the better for it.

Shared Spirit

Foerster: When it comes to visual effects, it’s crazy and exciting how fast the tools and parameters evolve. You are constantly behind the curve, no matter what. But what doesn’t change is the approach: How do we plan? What do we need to do on set to allow for the full potential of the VFX? And how do we do this in the most clever way, within the schedule and budget?

Nicholson: Now you are designing moves in virtual space, but you are still a cinematographer. You are choosing lenses, depth of field, lighting things. So, in that sense, what is the difference between a virtual cinematographer and a real-world photographer? They are both concerned, essentially, with the same things.

Beck: Some conventions have evolved over the 100-plus years of moviemaking, and they continue to evolve, but people have expectations about how a scene should look. Cinematic variables like framing, lighting, motion, and depth of field are all judged, even if subconsciously. Putting together a synthetic shot means taking on the obligation of controlling all those factors and making them meet not only the general aesthetic of cinema, but the aesthetic of the movie that the shot is dropping into.

“I suspect that one side effect of the change from photographic to digital effects work is that the younger generation of VFX practitioners lacks the instinctual knowledge of how lenses and cameras work in recording what is in front of them.”

— Mark Weingartner, ASC

Yuricich: It remains photography even if it is a digital methodology. You better have perspective, framing, and the shot had better look correct when capturing any VFX elements.

Krepela: Cinematography is the language of cinema. People have come to understand the rapid succession of images in a very distinct, intuitive way. Whether such images are produced on set or in the computer is not as important as the need for them to be rooted in the principles of cinematography.

Muren: We’ve had a tremendous boom in effects, and huge worldwide audiences want to see more. It’s hard to teach enough people fast enough how to do it. And one more thing — I wish there were more young effects supervisors who understood what our work is really about: communicating an emotion. But that’s a different story.

Foerster: In my opinion, the magic wand for the future is clear- and-open communication and collaboration between the art department, VFX and cinematography. The biggest shortcoming I see is the missed opportunities to be creative, innovative and efficient due to a lack of clear communication.

Weingartner: I do suspect that one side effect of the change from photographic to digital effects work is that the younger generation of VFX practitioners lacks the instinctual knowledge of how lenses and cameras work in recording what is in front of them. What [previous generations] came up absorbing on set, they have to make a conscious effort to grasp. By the same token, as VFX capabilities continue to expand, cinematographers don’t necessarily have a grasp of how their own process might be affected. And the truth is, the constantly expanding capabilities in the VFX world help us make shots that would not have been possible even a few years ago. It is foolish to get too nostalgic for the ‘good old days’ when we can do so much more now.

Taylor: I feel lucky to have been at this vantage point to see all the important scientific and technological developments in motion pictures. And that illustrates one of the important intersections between cinematography and visual effects: We in the visual-effects field have been able to give 1st-unit cinematographers a new tool set that they can bring to bear to overcome photographic storytelling challenges.