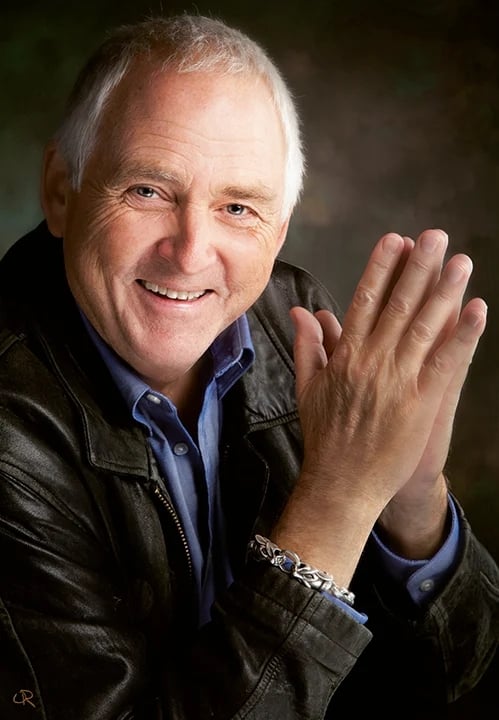

In Memoriam: Bruce Logan, ASC (1946-2025)

The cinematographer and visual effects expert was well-known for his contributions to such groundbreaking features as 2001: A Space Odyssey, Star Wars and Tron.

Born in Bushey Heath, England, on May 15, 1946, Society member Bruce Logan died on April 10 at the age of 78.

His father, Campbell Logan, was a director who worked for the BBC, and Bruce’s interest in filmmaking came to him at an early age. Educated at Merchant Taylor’s Guild School — where he studied math, physics and chemistry — he became an animator. At 19, he joined the visual effects team working on Stanley Kubrick‘s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), collaborating with visual effects supervisor Douglas Trumbull. Among other duties, Logan helped create numerous simulated computer graphics and readouts that were all done via traditional animation techniques and shot on 16mm film to then be rear-projected through prop video screens.

In a later interview, Logan remembered, “My last job on the movie was to shoot the opening scene of the film with the main title. Stanley was a stickler for quality and didn’t want any foreign country having a duplicate negative for the title in their language. So I had to shoot the sequence seven times in the various different languages.

“The shot was 1,440 frames long and it was five passes — the sun, the stars, the moon, the earth, and the title. It took me a day for each shot and was a fitting end to my work on the movie.”

In an interview with Los Angeles Post Production Group, Logan later said, “People ask me if I went to film school. I tell them I worked on 2001, A Space Odyssey. That was my film school.”

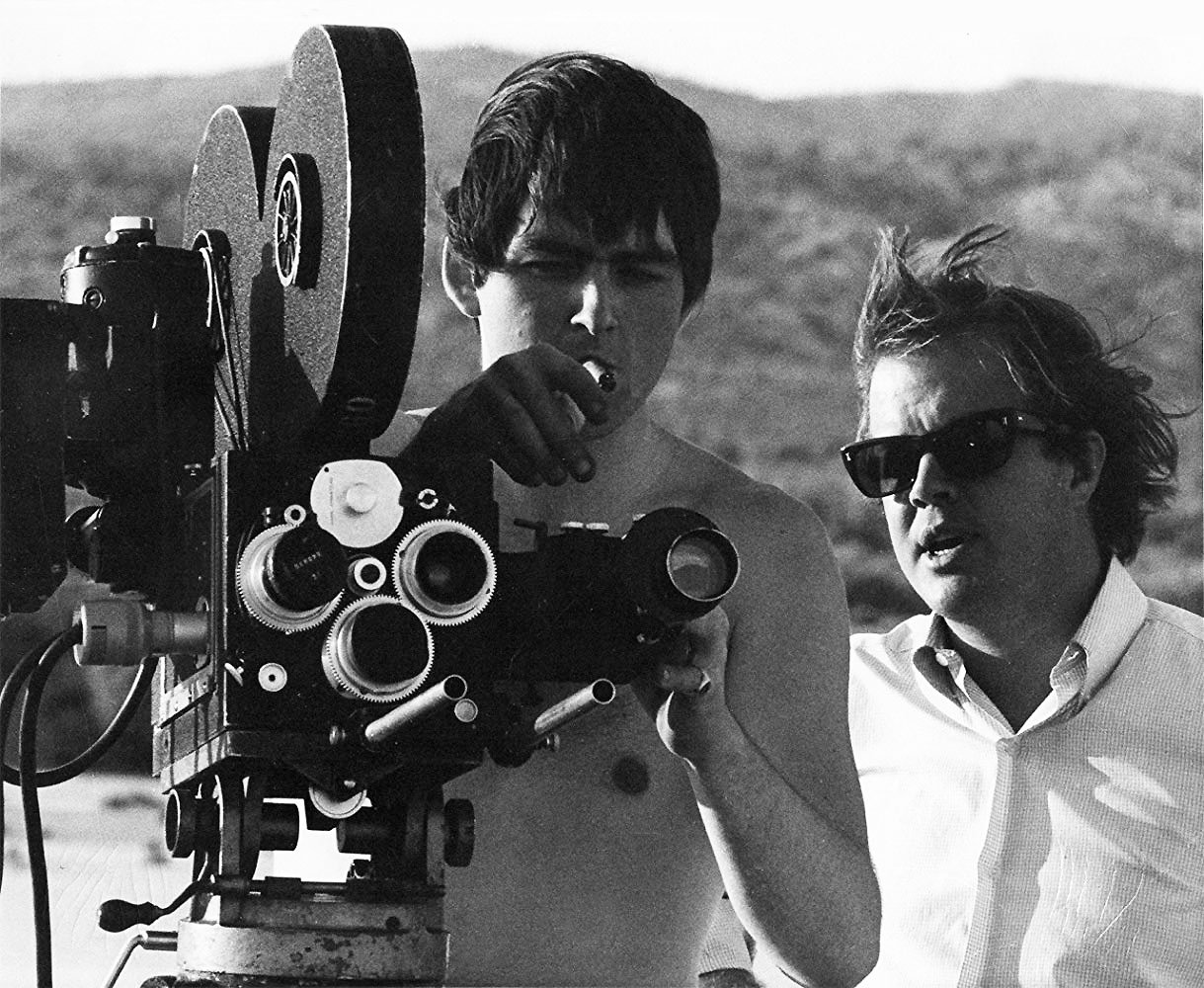

After moving to the U.S., he pursued working as a live-action cinematographer, and shot several indie efforts — including Idaho Transfer (1973), for director Peter Fonda — before a series of features for producer Roger Corman, including Big Bad Mama (1974), Crazy Mama (1975) and Jackson County Jail (1976).

Logan then worked as a visual-effects cinematographer within the VFX team working on the original Star Wars (1977), working alongside such ASC greats as John Dykstra, Richard Edlund and Dennis Muren. Among his contributions was running the high-speed camera for the destruction of the Death Star, working closely with pyrotechnics expert Joe Viskocil and devising the perfect angle: mounting the model on the ceiling and directing the lens straight up into it, creating a “zero-gravity” effect and the resulting blast expanding in all directions.

“When you shoot an explosion conventionally, with the camera straight and level, with forces of gravity and atmospherics acting on it, what you get is a mushroom cloud which doesn’t look like it’s exploding in outer space,“ Logan later wrote for zacuto.com. “By having the bomb explode directly overhead, it gives the illusion that there are no forces of gravity acting on the fireball, i.e. it’s in outer space!”

In a 2019 interview with AC about the history of visual effects work, Logan noted that the field “has always been about artistic content and the motion-picture camera process. I think of myself primarily as an artist, a cinematographer and a problem-solver. Those three aspects combined are the essence of visual effects.”

“Without intimate knowledge of the animation process, I wouldn’t have been able to optimize the live-action photography.”

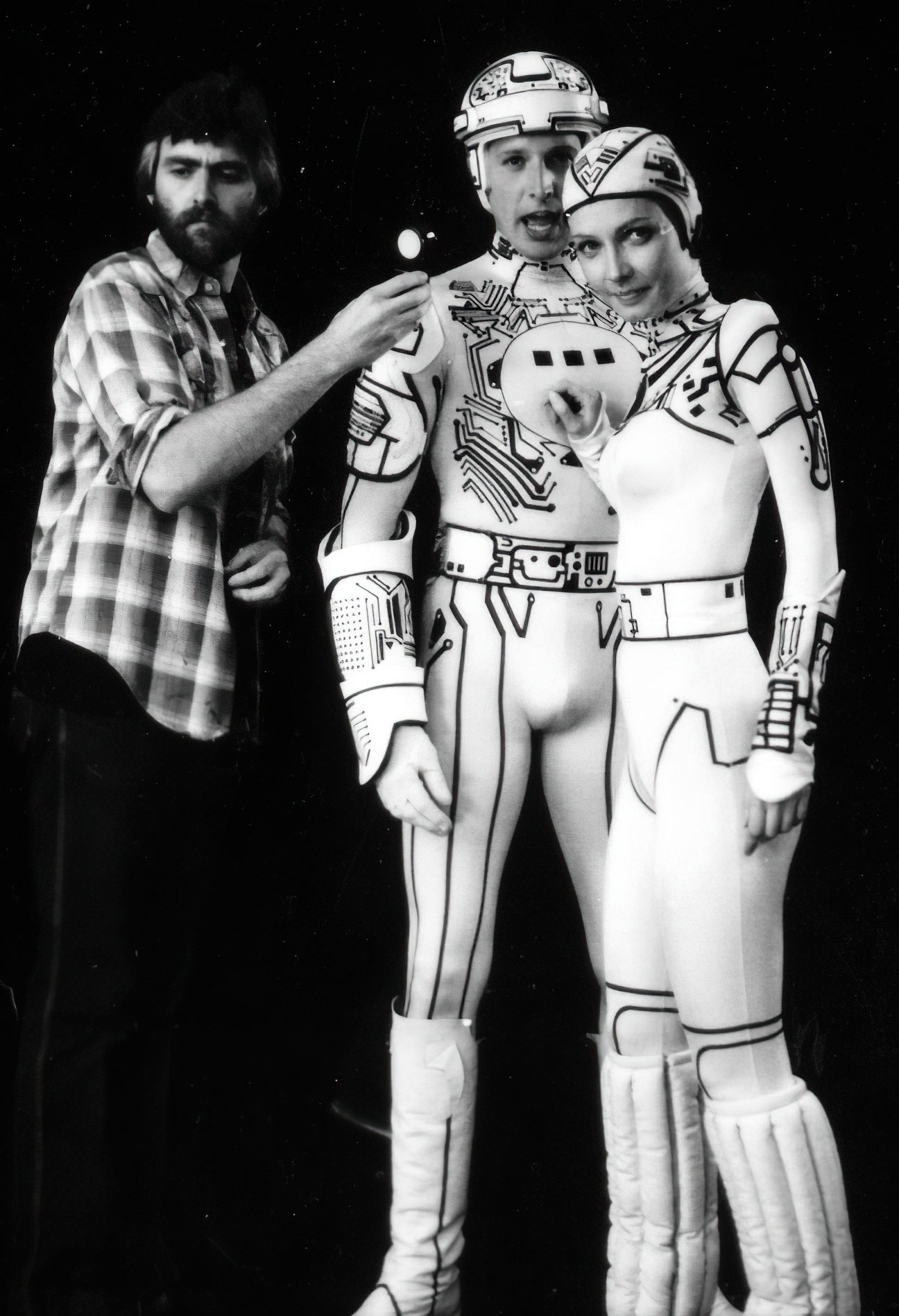

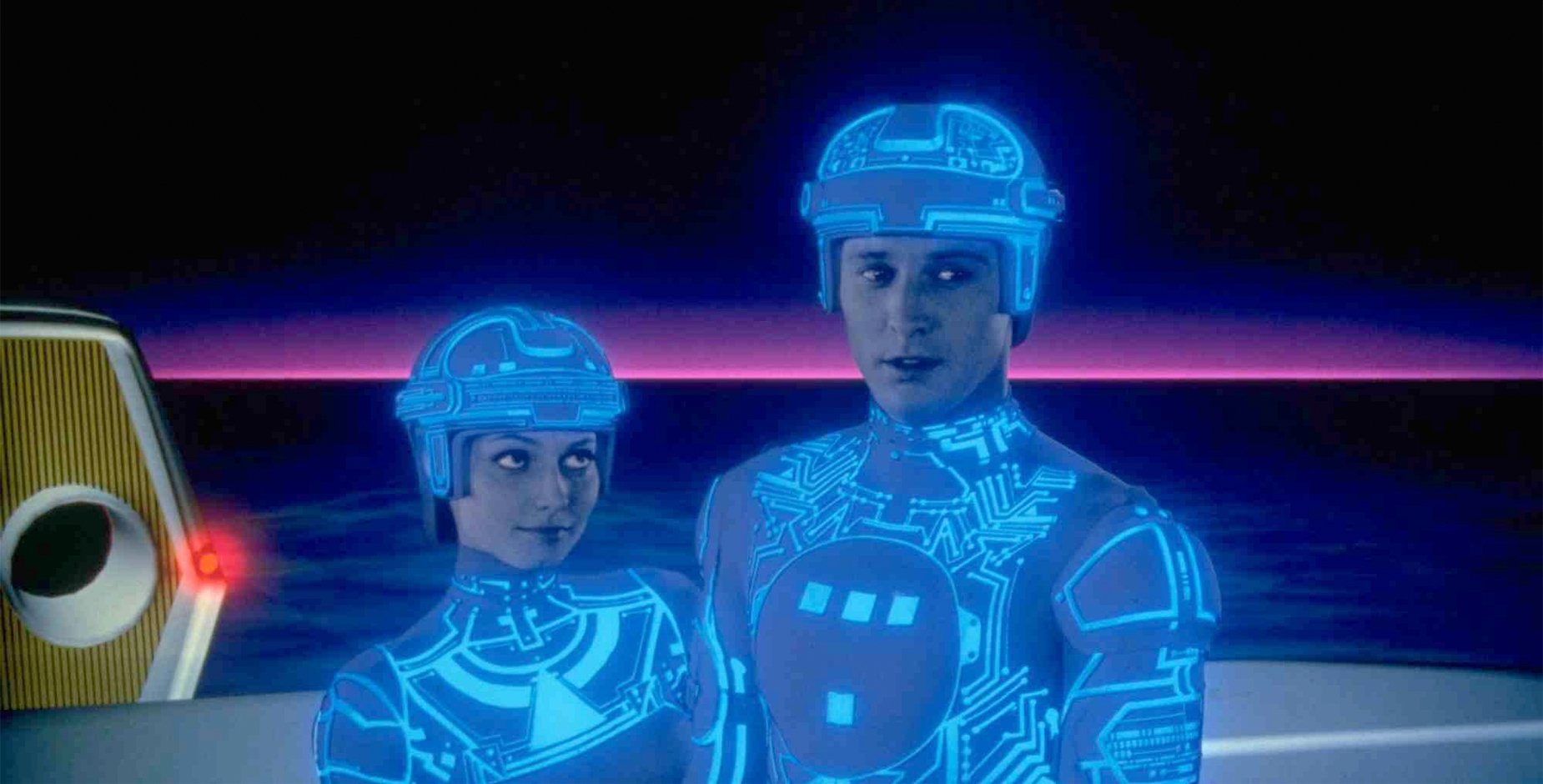

Memorably, it was Logan behind the camera during the making of the sci-fi classic Tron (1982), shooting live-action elements on 65mm film that would later be combined with optical effects and animation, then mixed with pioneering CG effects and elements to render a unique and memorable fantasy realm. “As director of photography on Tron, [which was among the first movies] to use CGI, I pulled heavily on my experience in animation and visual effects. In fact, every frame of film that I shot on that movie was duplicated onto Kodalith film, [and each] was used as an animation cel. Without intimate knowledge of the animation process, I wouldn’t have been able to optimize the live-action photography. Ultimately, I was creating a series of graphic images, so I had to completely eliminate motion blur and create infinite depth of field. Otherwise, the fine detail in the images would have disappeared.”

Tron helped shape the way production and post works together today, albeit with much more advanced tools, however, Logan noted, “even scenes with 100-percent CG imagery still use the basics of cinematography, even though the camera, lights and dolly are all virtual. I believe all the creative skills of the DP are required to create great CG images. And the skills required for managing a crew at 4:00 a.m. — lighting, cabling, placing wind and rain machines, and getting it done in the time allotted — that is a unique skill of the director of photography. On the other hand, getting 1,400 shots done in six months by multiple vendors also has challenges.

“I believe there is a blurring of the lines today between cinematography and visual effects, with the advent of virtual photography to drive CG characters and environments. If it is done well, you really don’t know what you are looking at — the work of the cinematographer or the work of a digital artist.”

Logan was also a member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and Directors Guild of America.

His daughter, Mary Grace Logan, noted on Instagram that her father changed the movie industry “before CGI ruled the screen” and was one of the “visionaries who lit the future by hand. From 2001: A Space Odyssey to Tron, my dad didn’t just work on movies — he made magic. A rebel with a camera, a pioneer with a story, and my personal hero.”

He is also survived by his wife, Mariana Campos-Logan.