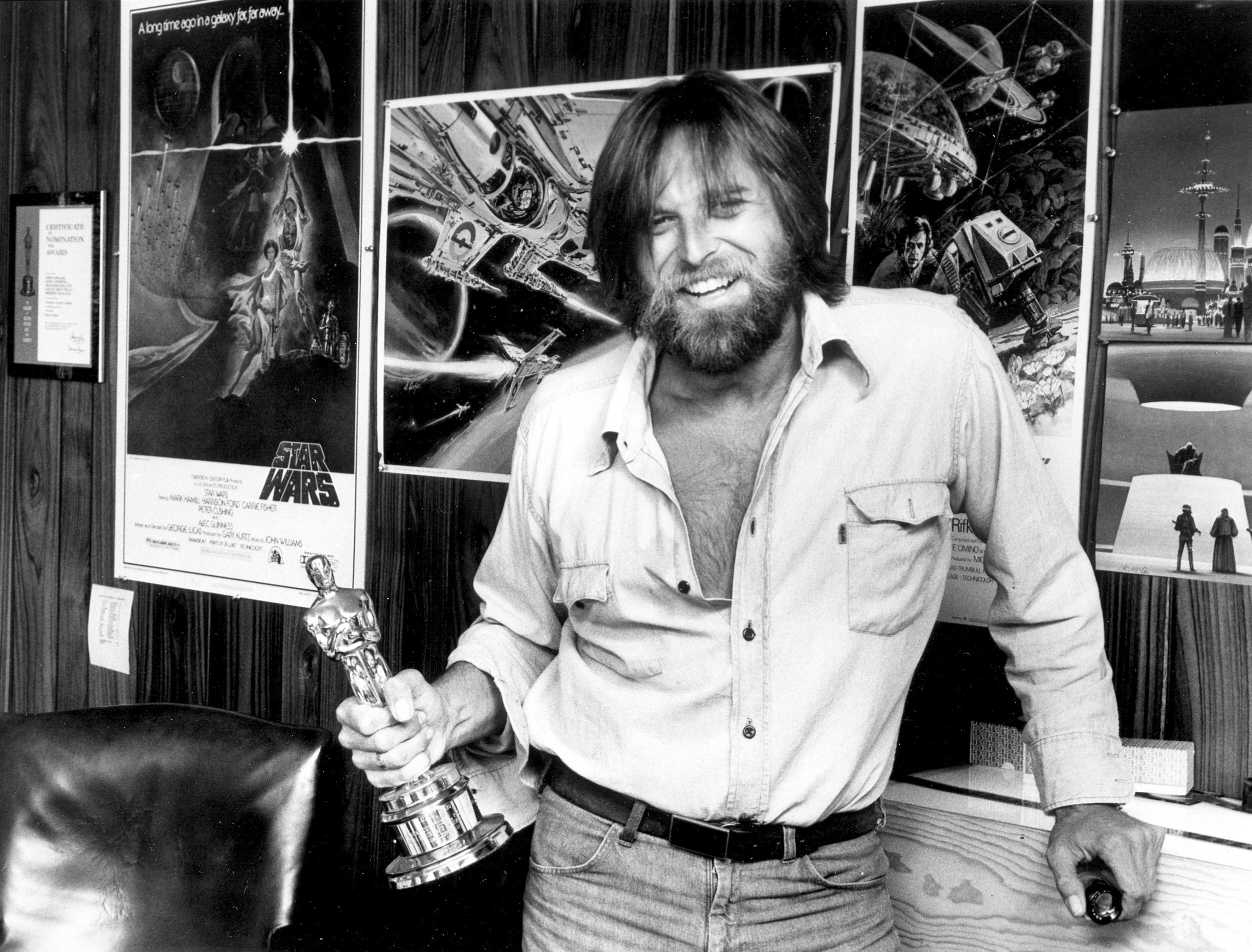

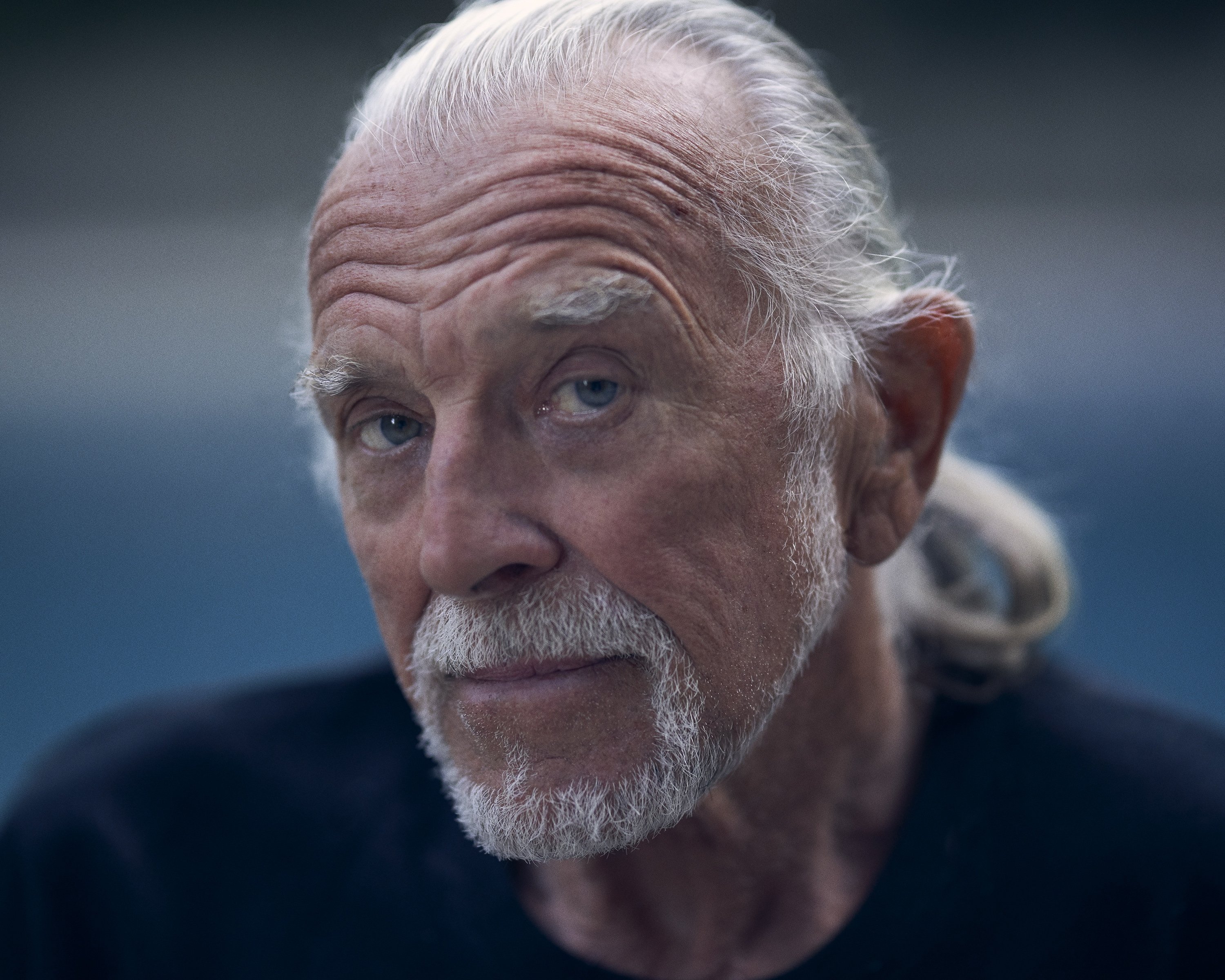

John Dykstra, ASC: Finding Joy in the Process

The Society member and visual-effects trailblazer looks back on his storied career.

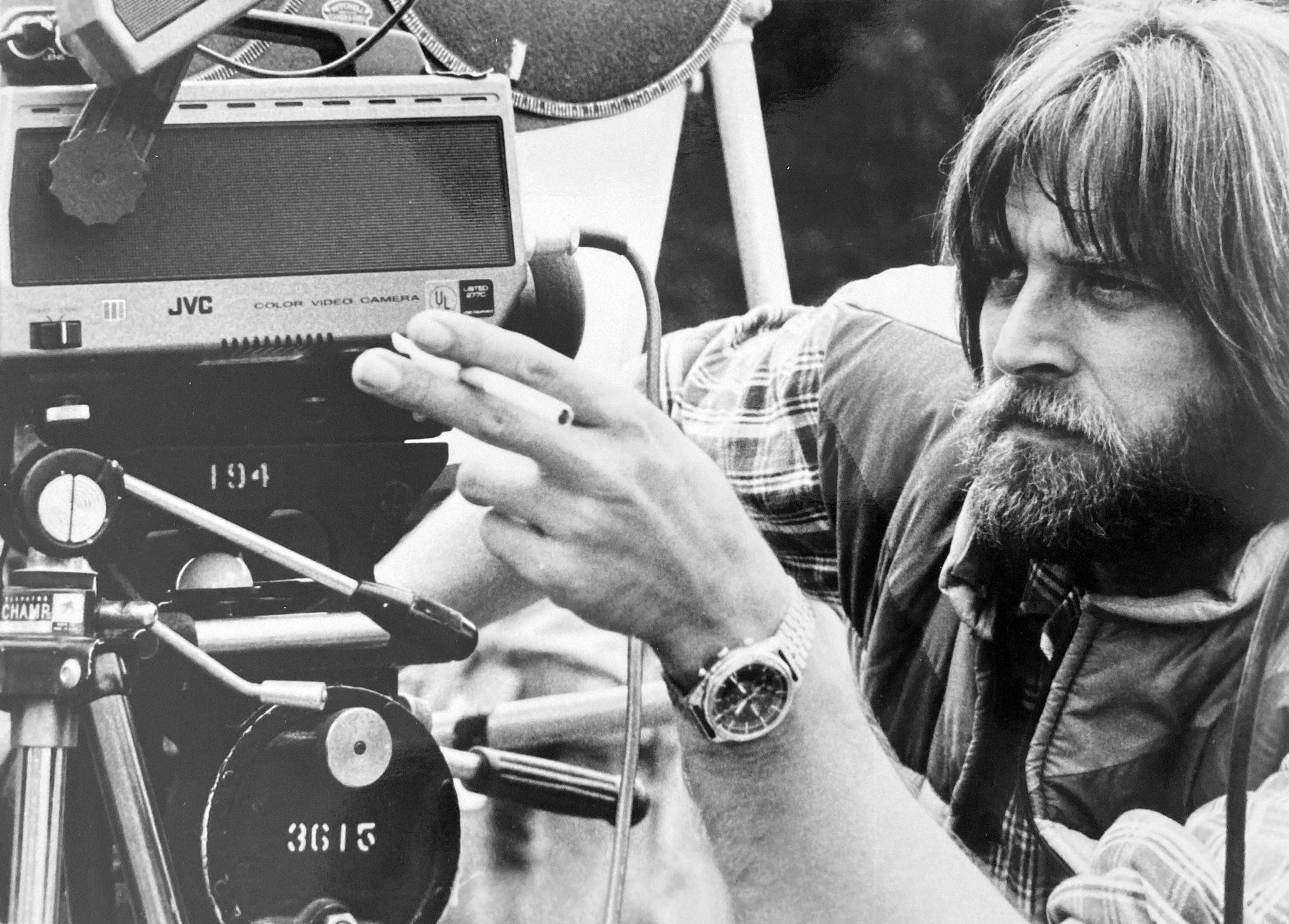

John Dykstra, ASC has been called a visual-effects titan, an iconoclast and a pioneer, but above all, he is a sincere, passionate advocate of the motion-picture image.

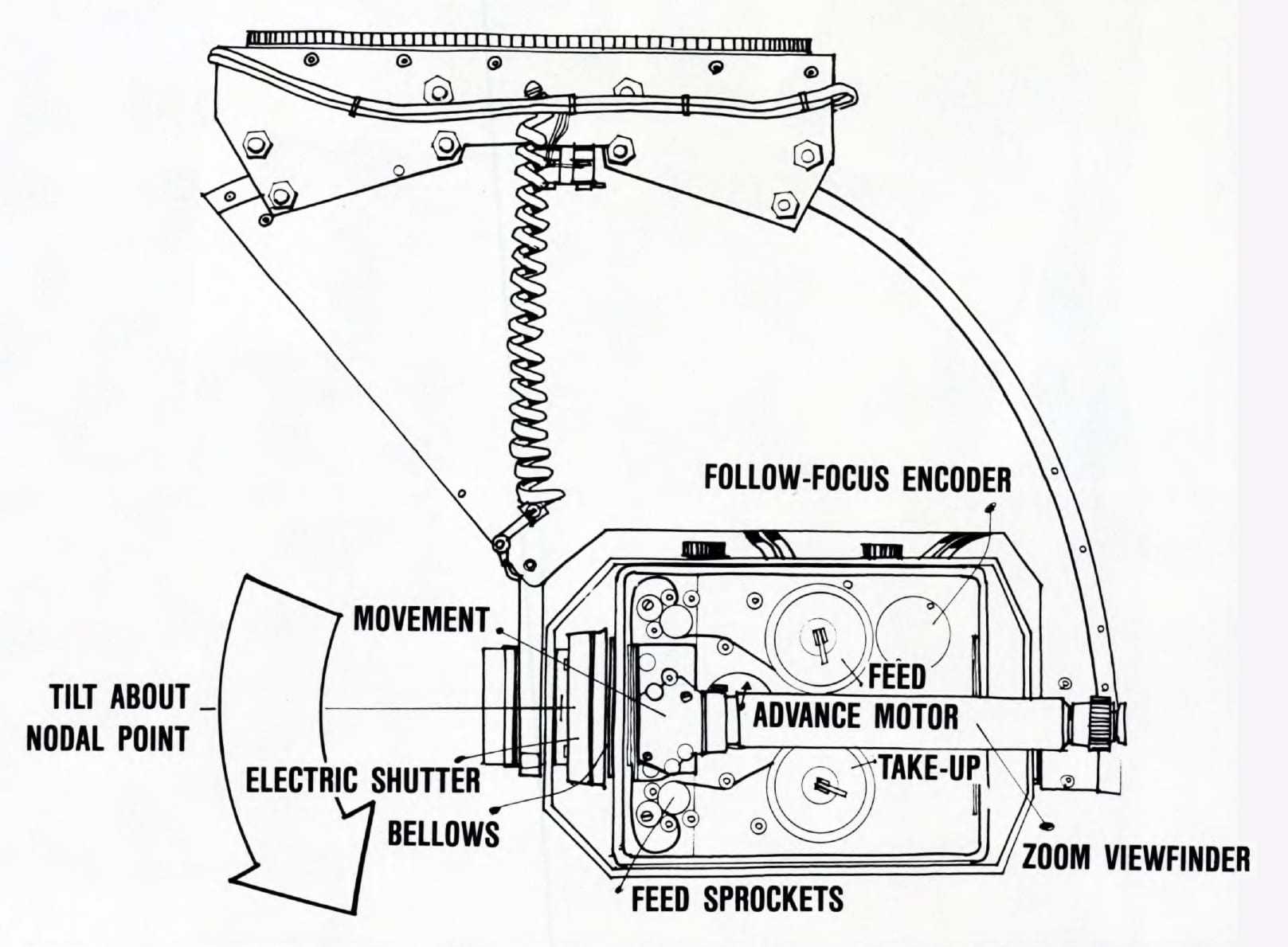

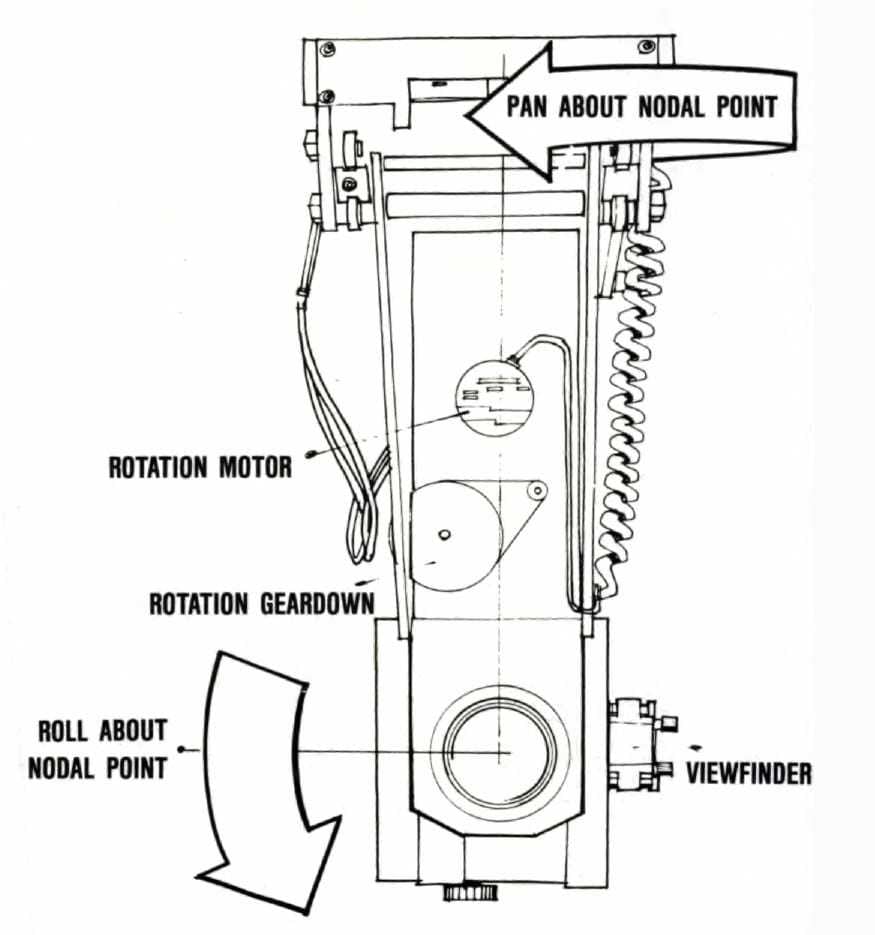

Dykstra has won two Academy Awards for visual effects, for Star Wars (AC July ’77) and Spider-Man 2. He received additional nominations for Spider-Man (AC June ’02), Stuart Little and Star Trek: The Motion Picture (AC Feb. ’80). He also shared an Academy Scientific and Engineering Award (with Alvah J. Miller and Jeffrey Jeffress) for developing the Dykstraflex camera and its electronic motion-control system for Star Wars.

Growing up in Long Beach, Calif., Dykstra was far more interested in surfing, cycling, kayaking and motorcycles than he was in the movies. “I wasn’t a cinephile,” he says. “Movies were just part of a much greater world experience.”

“I enjoy the process of interpreting the written page into ideas for images. That’s something I enjoy pretty much more than anything else.”

He notes, however, that “there’s a sensory input that comes from movies, just like there’s a sensory input that comes from being outdoors and doing things in the real world, and they’re not mutually exclusive. And there’s a satisfaction that comes from completing a piece of craft — whether it’s welding, woodworking, painting or printmaking. The mastery of the medium contributes to the satisfaction you feel when you end up with an object. I approached filmmaking and the business of pictures [that way]. I was driven by the process more than the final product.”

Tactile Flavors

Dykstra credits his father with instilling in him this fascination with process. “My dad was studying to be an architect when World War II broke out, and because of his educational background, he was given the option of changing his major to engineering. He ended up doing equipment design for an oil-field production company and worked in testing and evaluation for the Navy.

“He taught me how to draft when I was a little kid. I was around a lot of heavy equipment, and I learned to weld. There are tactile flavors in learning to weld, understanding the density of the material by listening to the sound it makes when you tap it; and understanding natural organic structures, how wood is stronger against the grain than along the grain. I also liked drawing, cartooning and sketching … and I did a lot of invention, kludging things together.”

Outside the Box

In 1967, Dykstra combined his interests in an industrial-design course at California State University Long Beach. His imagination soared with the counter-culture revolution. “I was part of that whole concept of, ‘If you remember the Sixties, you weren’t there,’” he says. “It was the hubris of a generation and our good fortune that society and world culture embraced it. The idea of free thinking comes from the view: Don’t let yourself get painted into a box. When they said, ‘Go outside the box,’ I hadn’t a long way to go!”

Dykstra’s academic pursuits included the production of a 16mm film on the theme of Industrial Living Environments, sponsored by Alcoa Corp. That experience, which included visiting New York City to submit his presentation, convinced him he was not cut out for a button-down work environment.

“When you go to work for Ford, you start out designing door handles. I liked bigger-picture concepts — positing an overall solution to a problem without having to solve every step in the process. It was fun to be a dreamer without having to be responsible for the execution of every facet of that dream. And that’s an ideal definition of what filmmakers do.”

The Trumbull Years

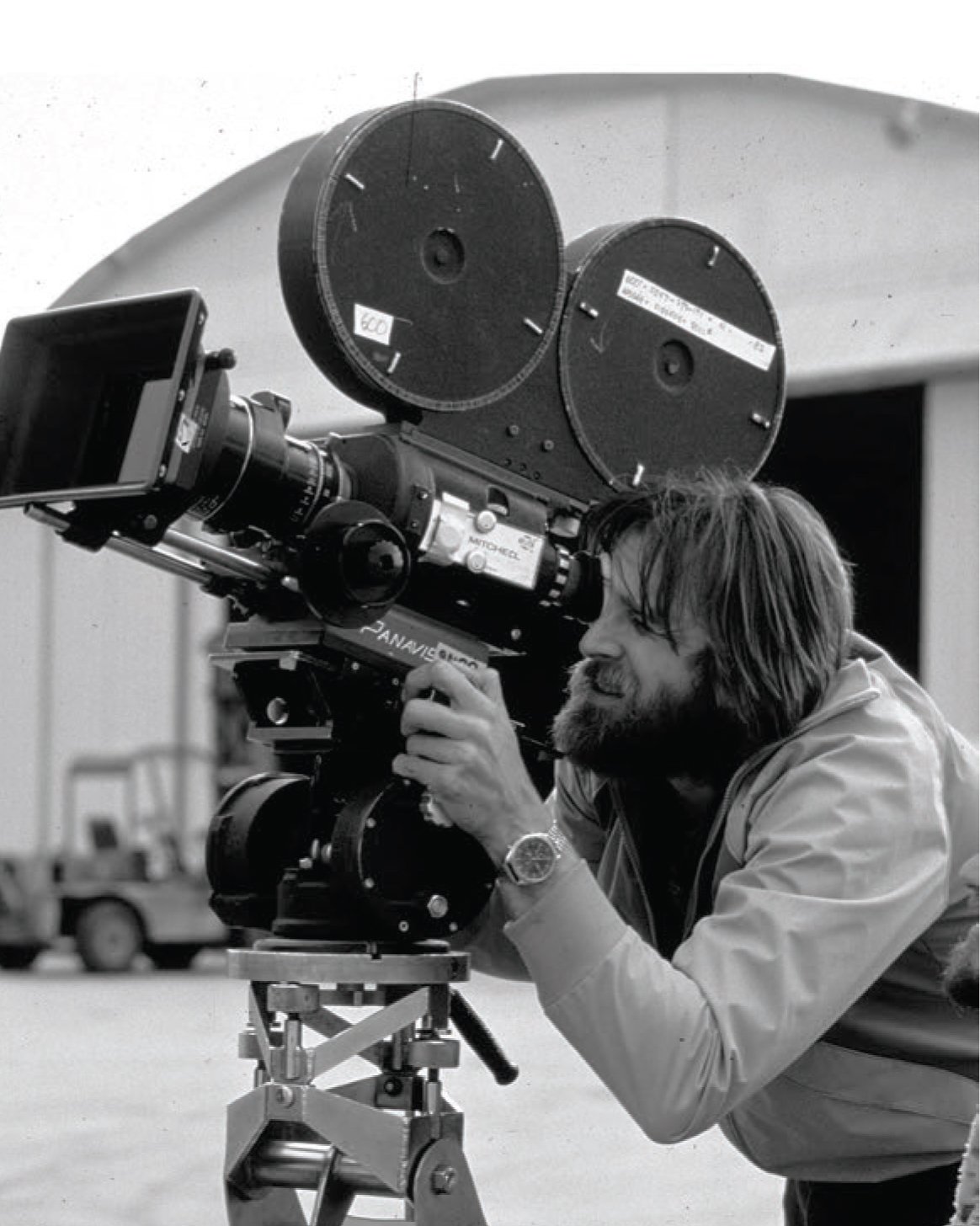

Back in California, Dykstra began shooting stills of rock bands, and he drew on these skills when he joined a group of young artists working with Douglas Trumbull on Robert Wise’s The Andromeda Strain (AC May ’71). He recalls, “Doug liked hiring people out of school, [and his studio] was like a design salon. I’d been involved in still photography — doing posterization, solarization and image manipulation of multiple images composited together. For The Andromeda Strain, I made a graphic globe with dots, and the dots were migrating around the surface of the globe; that was put together as a multiple-layered composite in a motion-picture camera.

“The more design and modelmaking I did for Doug, the more opportunities I had to integrate photography, and Doug allowed me to do photography for some of the films he was working on. I worked on designs, made and photographed models, and built rigs that moved the camera. It was a collaborative effort.”

For exteriors of giant spacecraft traversing Saturn in Silent Running, which Trumbull directed and Charles F. Wheeler, ASC shot (AC July ’72), Dykstra and his collaborators filmed an intricate, 26’-long miniature using robust ex-military cameras for repeat-pass photography.

“Mitchell built scads of cameras for the government, and they were pretty basic — just the box, and some had a gusset on the back for hand-cranking,” Dykstra recalls. “But they were beautiful machines, robust and incredibly reliable. You could buy one with all of its support accessories for $2,500, and they were sold in lots, so we had many of those. They were pin-registered, which meant we could do multiple passes and the image wouldn’t bounce. We had to tweak them to make sure the curve on the claw that pulled the film down was smooth. Tweaking the pulldown claws and pins was a form of black magic, and I don’t know if you can find people who can do that anymore.”

The cameras ran on a custom-geared track, with motors tied to a gear system on the track and to a gear system on the camera, which allowed long exposures to capture extended depths of field and repeat passes for multiple exposures. “An important element of this kind of photography is that the camera moved continuously during exposure and pulldown,” Dykstra explains. “That caused the natural motion blur that occurs in live cinematography and eliminated the ‘steppiness’ seen in traditional stop-motion photography. The system ran at one speed. It was a drive motor and several synchro-motors synchronized to the main motor through gears.

“Now, the problem was that it was linear. Everything moved at the same time, but you couldn’t accelerate or decelerate any axis because it was all driven by the same motor, and if you accelerated or decelerated the motor, then the exposure would go off. You could change the velocity between any two motors in terms of how quickly or how far they moved the subject by gearing, but you couldn’t accelerate or decelerate that setting.”

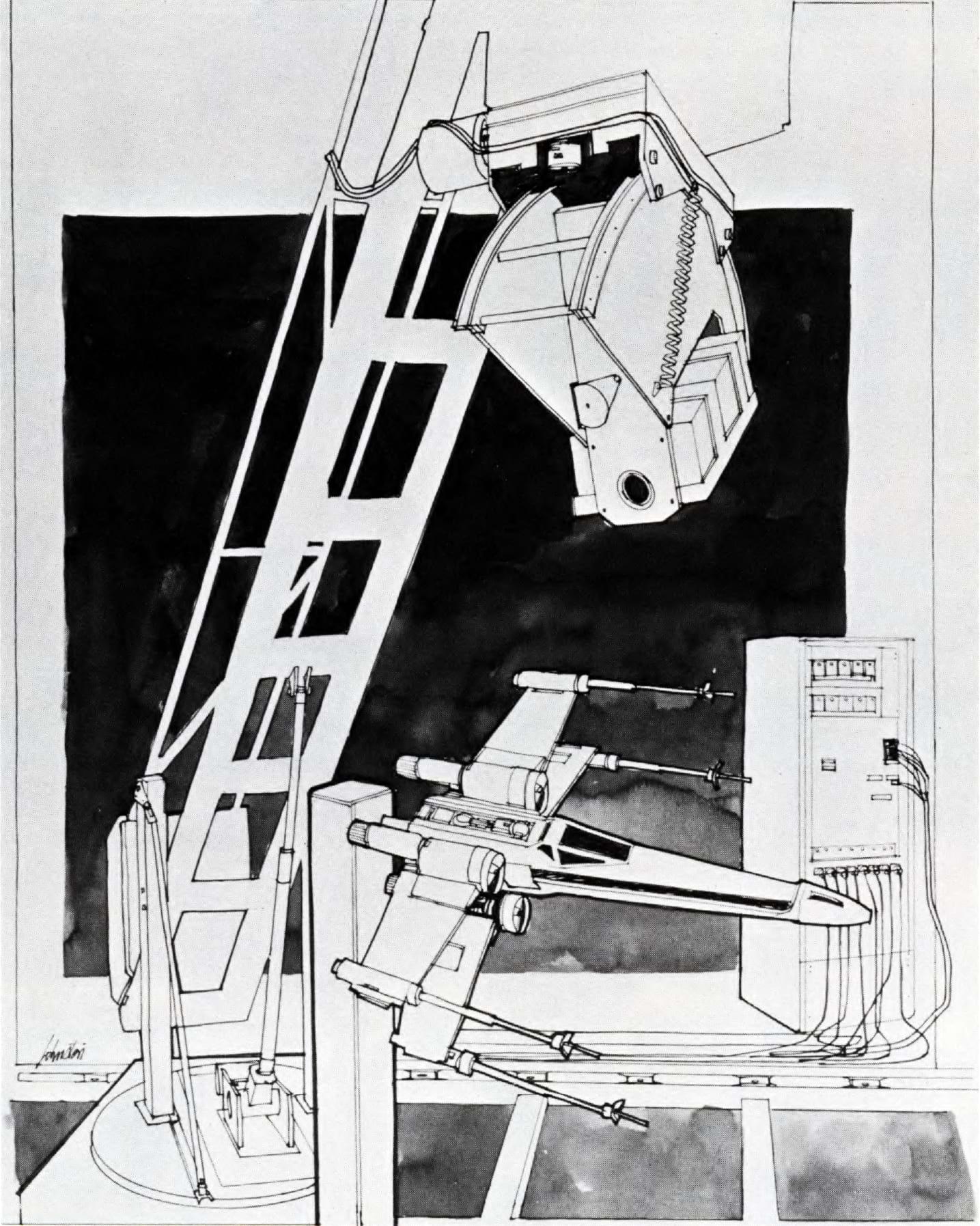

Birth of the Dykstraflex

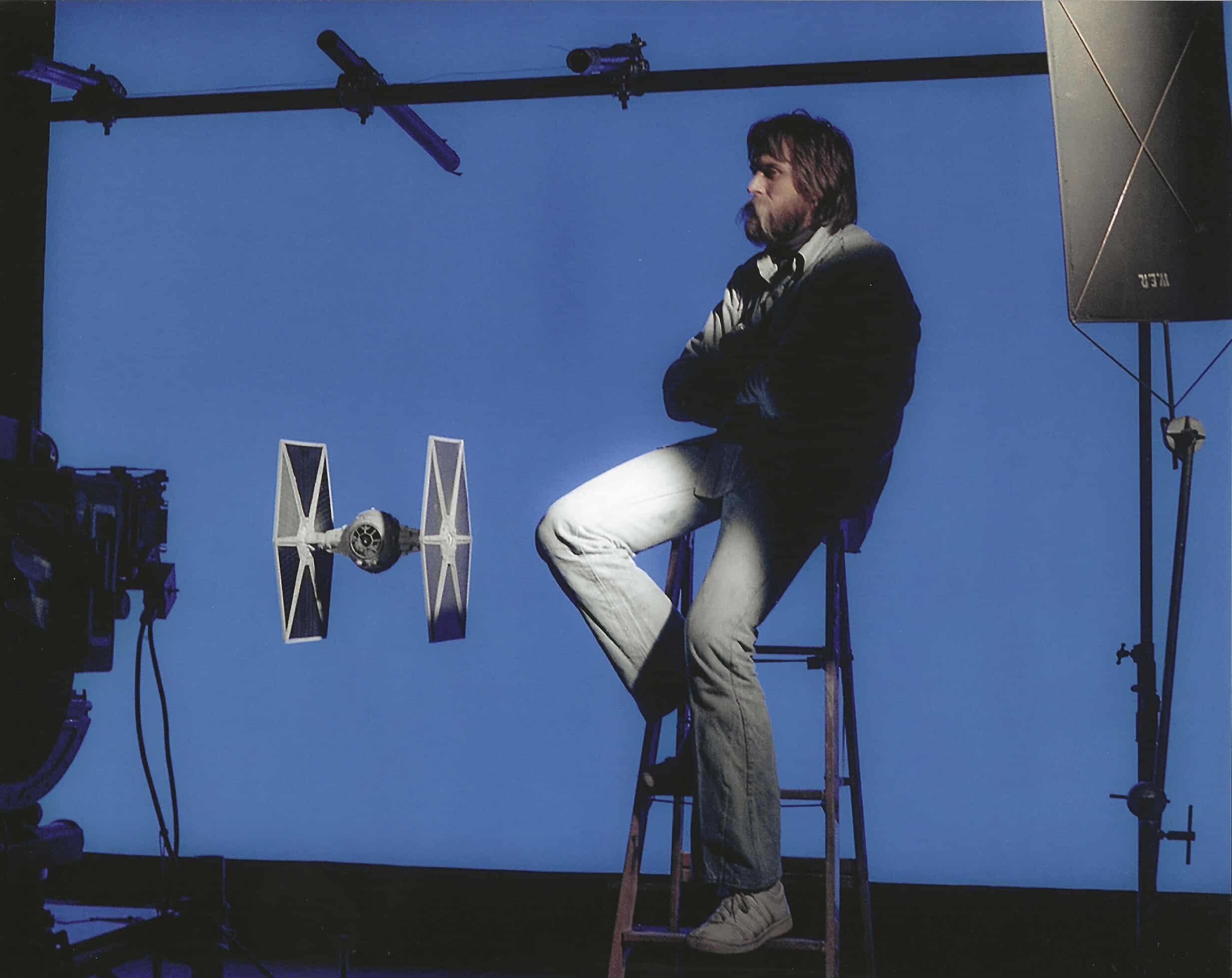

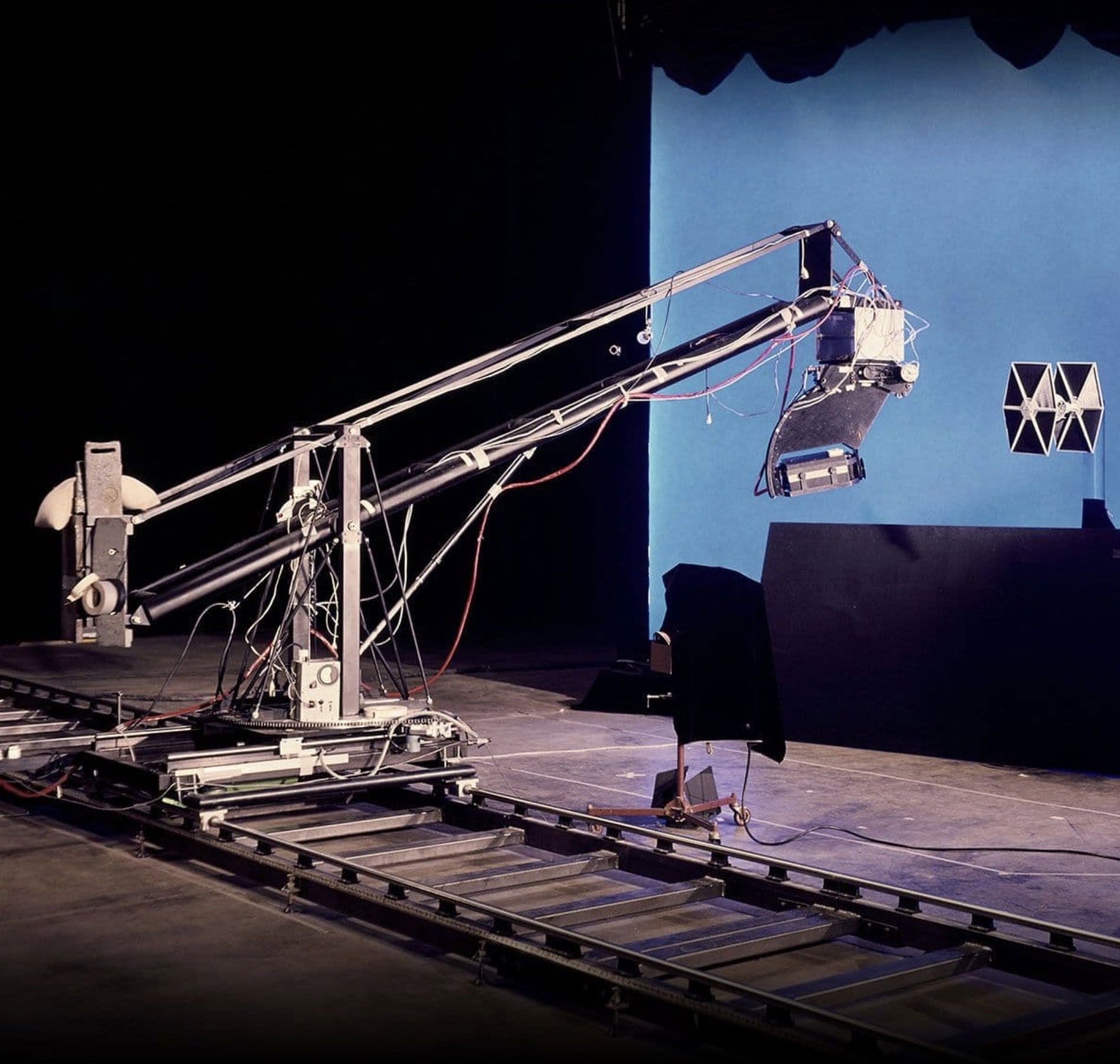

Dykstra experimented with more dexterous miniature photography at the University of California-Berkeley Environmental Simulation Laboratory. For a civic-planning study, he helped to create roving, street-level views of Marin County using a 16mm snorkel lens. on a computer-controlled camera that was suspended from a trellis and skimmed miniature landscapes. “The system was partially designed when I joined the project,” Dykstra says. “I contributed to refining the design of the optics, the mechanics and the computer interfaces.” The technology informed Dykstra’s thinking when Trumbull, busy with other projects, referred his young protégé to George Lucas and Gary Kurtz, who were seeking a method of filming dynamic space battles for Star Wars at the fledgling Industrial Light & Magic.

Dykstra’s solution — the computer-controlled Dykstraflex, with its seven-axis camera dolly and head supporting a VistaVision camera on a custom dolly track — operated on the principles of a multi-track sound recording. He explains, “The first element was the idea that you could record motion as multi-track. Channel One is the camera; it runs at this speed. There is an exterior clock that’s running constantly, and if you change that clock, you change the overall system speed. But because you’re recording multi-track, you can vary the speed on individual channels independently. That means you can have an acceleration or a deceleration or a pause independent of camera speed and exposure, and they can occur in the entire system or on individual channels.

“The ability to vary the speed on any given channel relative to the continuous clock that’s giving you the exposure was really the key. And all the moves were continuous during exposure and repeatable, which was also key. We could pan and tilt with accelerations and decelerations — we had the fluidity of the moving head. And by making that head repeatable, we could put multiple subjects in front of the same camera, photograph separate elements, and give the impression that they were all photographed at the same time.

The innovation was lightning in a bottle. “I loved being able to think in three dimensions — that came naturally to me. I loved the idea of being able to create an adrenaline rush. And I loved working with experienced people who were also knowledgeable about their colleagues’ fields of work. You didn’t have to interpret documents to get across to the modelmaker what was needed when the model was in front of the camera, because the modelmaker knew how to take pictures, too. That original ILM crew’s experience and willingness to collaborate was what made the Star Wars visual-effects whole greater than the sum of its parts.”

Apogee and Beyond

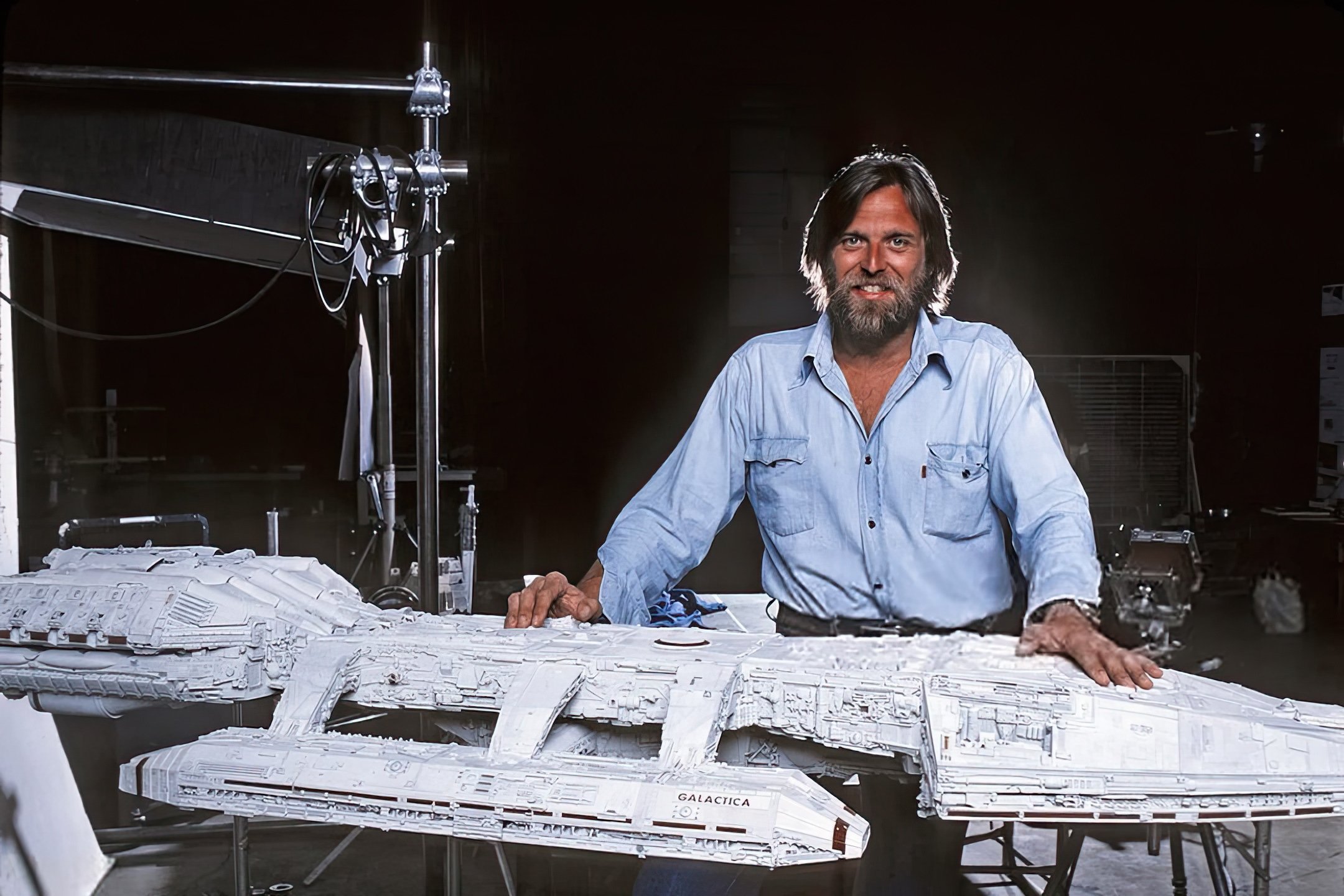

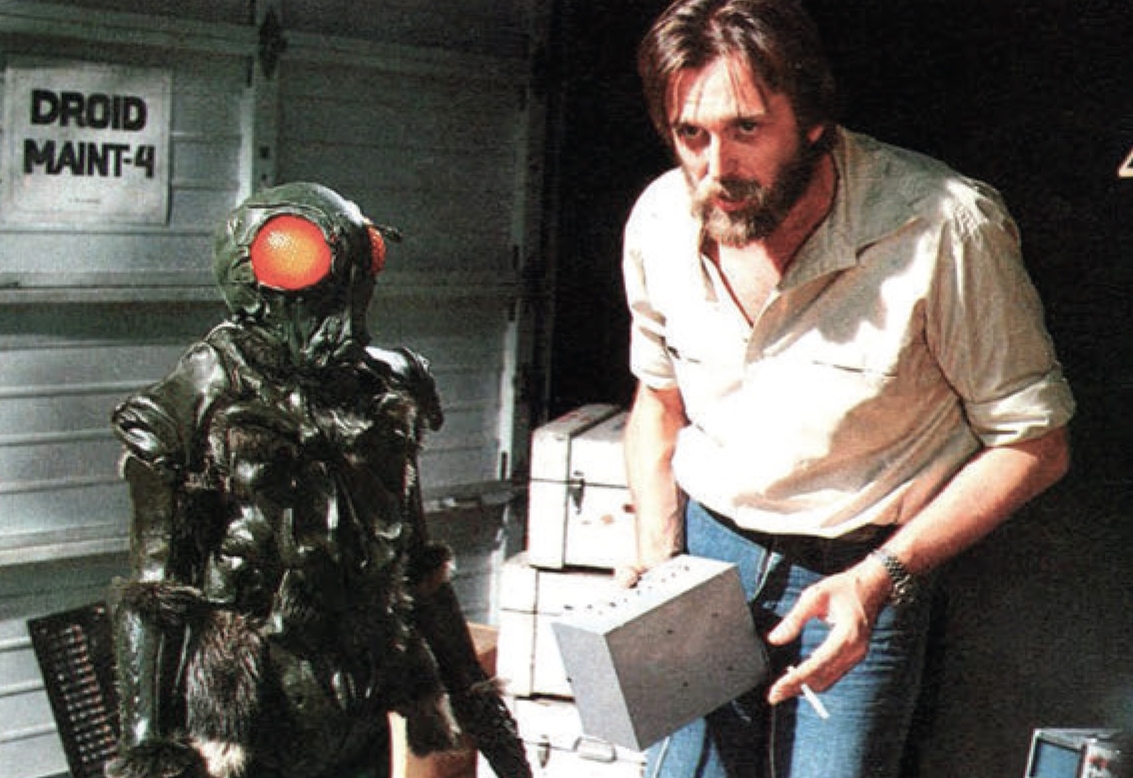

From 1978 into the 1990s, Dykstra applied the same work ethic at his own visual-effects company, Apogee Productions, which contributed to such productions as Star Trek: The Motion Picture, Firefox, Lifeforce, Big, Die Hard 2 and the original Battlestar Galactica series.

“I failed upward!” he jokes. “We did some great stuff, but not all the movies we worked on became touchstones in the way that ILM was founded with Star Wars. The thing I’m proudest of is the culture, the people who worked there.”

He moved on to become a visual-effects designer to the emerging digital realm at Sony Picture Imageworks. “There was one tool: the computer — the box,” he notes. “And the problem for the people who grew up on the box is that they needed to recreate anomalies that happen in the real world. It’s messiness and the visual threat of catastrophic failure that give you the adrenaline rush. If you want to know how to [create visual effects] on a computer, my advice is to buy a simple manual still camera and go out and learn about depth of field, the focal length of lenses, and film format in analog terms — and a few real-life adrenaline rushes for reference.”

Dykstra focused on developing a rapport with the filmmakers. “It became less about how the image was made and more about what the image means. The thing I enjoy about working with directors is that I get to be privy to their creative expertise, and it’s an incredible world to live and learn in because these people are born thinking out of the box.”

Return to Analog

Over the last decade, Dykstra has enjoyed a creative rapport with Quentin Tarantino and Robert Richardson, ASC on Inglourious Basterds (AC Sept. ’09), Django Unchained (AC Jan. ’13), The Hateful Eight (AC Dec. ’15) and Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (AC Aug. ’19).

“Quentin likes the analog process of filmmaking, so my responsibility when I’m working with him is to figure out a way to create images without defaulting to CGI,” Dykstra says. “He’s willing to take the time to explore techniques and learn what their limitations are. I enjoy that he’s willing to talk about the physics of the subject of the effect and how that’s influenced by the process that captures it, and whether that enhances or detracts from his intent. He lets me composite digitally because of the improvement in quality and because there are few, if any, optical printers left. But for the most part, he prefers more traditional analog effects.”

A particularly memorable set piece he helped create for Tarantino was the incineration of a movie theater full of Nazis at the climax of Inglourious Basterds. Noting that his key collaborators included production designer David Wasco and special-effects supervisors Uli Nefzer and Gerd Feuchter, Dykstra calls the scene “a potpourri of old technology — a choreography of mechanical effects, stunt people and high-speed cameras. For one shot we created fog with liquid nitrogen and photographed it upside down at high speed to make it feel like it was billowing up.”

The climactic moment was staged at Studio Babelsberg and on a duplicate set rigged to burn in a defunct factory outside Berlin. A battery of DLP projectors simulated the theater projector’s imagery of Shosanna Dreyfus (Mélanie Laurent) laughing amid the inferno. “The tricky thing with that was making the screen burn at exactly the right rate so it would obscure the projected picture at the right moment,” Dykstra recalls. “The area behind the screen had to be on fire, and those were real people in the seats. We had 18-wheelers outside containing propane. There were 10 people on a rostrum operating handles; they had flame boxes that allowed the fire to go up the wall, sourced from multiple fixtures and diffused through a special box system that the mechanical effects guys came up with. That was choreographed to the projection of the image of [Laurent] laughing, which was synchronized to igniters at the bottom of the screen. The screen was composed of ground-up Ping-Pong balls, and nitrocellulose, which had to be slightly damp to burn at the right rate. When Quentin yelled, ‘Action!’ all of that had to happen in sync!”

Ideas for Images

Today, Dykstra consults on emerging technologies. “What’s fun about technology at this point is that we’ve run out of the ‘gee-whiz-ness’ of it all. Your phone is now a camera and a computer, and as we become conditioned to that, the mystery and magic go away.

“Virtual production is interesting because it’s bringing computer imagery and its capabilities into the real world, relying on motion-control concepts to synchronize the two. It brings new technology into our analog world in unique ways.”

Whatever the method turns out to be, he adds, “I enjoy the process of interpreting the written page into ideas for images. That’s something I enjoy pretty much more than anything else.”

In AC’s July ’77 issue, Dykstra authored the article Miniature and Technical Special Effects for Star Wars.