A Return to Oz

Cinematographer David Watkin, BSC discusses the pressure of re-visiting one of Hollywood's most beloved settings once again with Dorothy Gale.

This article was originally published in AC May, 1985

Set photos by Barry Peake, Richard Blanshard, and Douglas Dawson

The main ingredients of a fantasy film are a healthy dose of realism and a heaping spoonful of magic. Return to Oz, a Walt Disney Films release, has the requisite amounts of this contrary mix. Director Walter Murch has been to Oz, just as surely as Victor Fleming had been, and though what he saw in the Emerald City is different from what Mr. Fleming saw, it is still most wonderfully Oz.

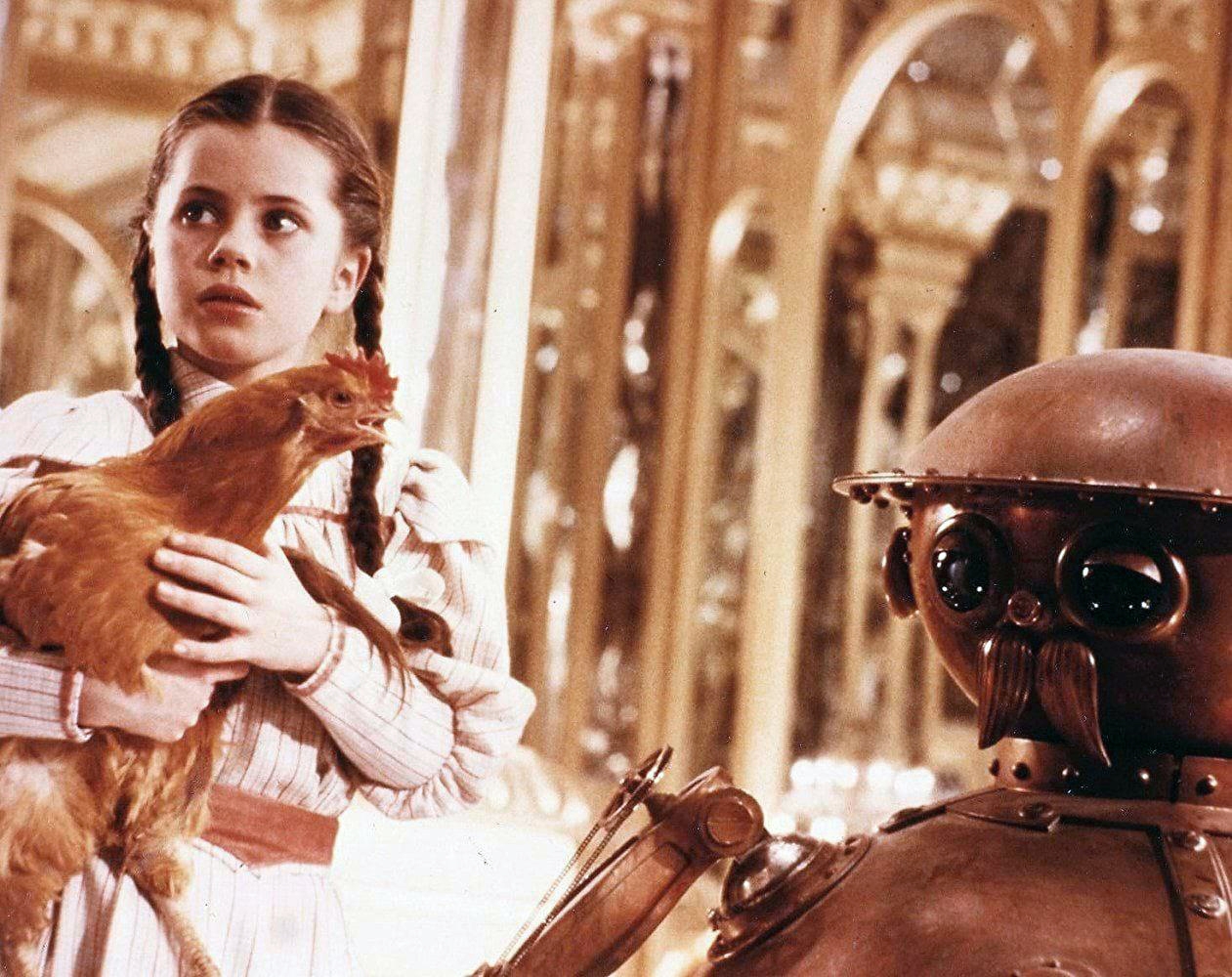

The story is based on at least two L. Frank Baum books — Ozma of Oz and The Land of Oz — and contains an imaginative cast of characters. Dorothy, played by Fairuza Balk, is joined by a group of surprisingly human mechanicals. There is the round-faced, round-bellied Tik Tok, a clockwork man; Jack Pumpkinhead; Billina, the talking hen; the incredible flying Gump; and the familiar Scarecrow, Tin Woodman and Cowardly Lion. This story contains not only an evil witch, but the terrible Nome King, and it is rather hard to tell just what he is — a rock-like human or a human-like rock.

“If we had tried to do a remake, I wouldn’t have been too keen about being involved in it. I’m not a great believer in remakes. They are never as good as the original. But this is a combination of two other Frank Baum books. It is a sequel — a totally different story.”

— David Watkin, BSC

Disney’s new Oz depends on a wide variety of special effects to create the realistic world of Dorothy and her friends. Many talented people contributed to the magic of the film. Highlighted here are the creature design supervisor, Lyle Conway; the clay animation supervisor, Will Vinton; and last, but certainly not least, David Watkin, BSC — the director of photography on this new journey to Oz.

Conway, the Merlin Olsen of Muppetland, was the organizing force behind the creature shop. Originally from Illinois, he has worked on most of the major fairy tales that have come out in the last six years. He sculpted the alluring Augra and the terrible Skeksis for Dark Crystal as well as the lovable head of Miss Piggy for various Henson productions. His trip to Oz was followed by a trip to Wonderland for the film Dream Lovers where he helped bring to life the incredible creatures first imagined by Lewis Carroll.

He and his crew designed and manufactured the radio- and cable-controlled creatures and the suits for the creatures that accommodate a human inside. More than a year was spent in preproduction, building — among other curious things — the perfect animatronic chicken. It may sound silly, but it was no laughing matter.

“Billina was my favorite,” Conway said. “In the beginning, I tried to get them to use a chicken. We got what became the house chicken and let me tell you, boy, are they stupid! They are probably the most stupid animal I have ever run across. They just won’t do anything.” Obviously, this could be a problem. Especially since Billina had to be able to beak sync.

“When we discovered how dumb chickens were, some people actually talked seriously about a little person in a chicken suit. I suggested our shop do a mock-up of an animatronic chicken head to show how it would work. In the end, there were about five versions of Billina. Some had cables in the head, some were radio-controlled, some had a hand in the neck. The wings were sometimes rods and sometimes radio-controlled, plus we used a real chicken for some shots,” Conway continued.

“Part of the process of designing Billina was arriving at what color she should be. So one day we went down to the casting coop and brought back a half a dozen chickens and Walter picked out one he liked. Then we went out and found feathers to match. What we didn’t realize was chickens change color about halfway through the year. So our chicken wrangler finally got some eggs and raised our chickens from scratch (argh!). Anyway, it turned out that young chickens were darker than the older chickens, so it was a constant battle to get the right-age chicken. There was one scene we shot as our chicken was beginning to molt. There is Dorothy, petting the chicken and pulling out great wads of feathers. We had to find a chicken that wasn’t molting.”

There were some minor problems with the real Billina, but the difficulties with the animated version were greater — even a little scary — because even a fantasy chicken has to move like a real one. “She did scare me at first, but if it doesn’t scare me, I shouldn’t do it. When things get really easy and you start to do them with your eyes closed, they get very boring,” said Conway. “She was the most difficult thing to create. It is very hard to do something that is real because people know how they should move. She is a real pretty puppet and definitely my favorite . . . next to the Gump.”

Most of the creatures were based on the John R. Neill illustrations from the original Oz books. There were some minor exceptions and the Gump was one of them. Originally, the Gump was a kind of goat with one deer antler. Murch pictured him more like a moose and moose he became. Still, it is very difficult to get a moose to talk.

“The Gump was mechanically the most difficult to make,” reported Conway. “He has a lot of dialogue and a lot of lips. We had to come up with something that would form syllables. Nick Rayburn, who did the close-up, mechanized heads for Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes (1984), did the lip and head mechanism for him. He is all cable-controlled. Val Jones came up with the knitted fabric which covered the mechanicals. Without the fabric, I don’t think either of these puppets could have been done. It compresses and stretches without folding. If it is mounted on the neck taut, it gives and stretches like skin.” For Billina, each feather was inserted into the cloth. For the Gump, the fur was pulled through the material a little at a time.

“The Gump’s head is attached to a sofa and the whole thing flies through the air. We tried to give a bit of a galloping motion to his neck. In addition, he can turn his head, wiggle his ears, and, of course, talk. He’s a lot like me — even though I was only his mouth, I sort of coordinated the rest of it. It is very difficult to get a good organic look in something that is totally mechanical.”

It took eight people to manipulate all the cables for the Gump. The team had only two weeks of rehearsal before shooting. At first, “it was a nightmare,” Conway said. “Nothing was coming together. So, I tried to think of something that would pull everybody together. You really have to work as one to make it look right. I got a recording of Frank Sinatra’s ‘My Way’ to rehearse to and literally, within an hour everybody was doing it. It is a familiar song with a very predictable range of emotions. Responding to it got us working as a team.”

The other mostly mechanical creature is Jack Pumpkinhead. “Our work on Oz started with long talks with Walter about the personality of the various creatures. We talked about Jack and the look of his head. Walter had very specific ideas. He saw Jack as being imprisoned within this constant grin. No matter what he felt or experienced, he would always be saddled with this grin. We went through quite a few finished, colored prototypes — non-mechanized — before we came up with the final version.”

Part of the time Jack Pumpkinhead is manipulated by Brian Henson, Jim Henson’s son, from a specially made cart. Brian would lie on his back and push himself and Jack around on the cart using his feet. “Jack was originally designed so that there was no movement in the head at all, but Gary Kurtz suggested that the head squash (argh!) and stretch to show surprise, so there is a very subtle movement, but that is all. Jack loses his head and it turns over so we had several replacement heads and managed the scenes with cuts,” recalled Conway.

Tik Tok, the clockwork man, is not strictly mechanical. “Tik Tok is made out of fiberglass and is vacuum-plated to look like copper,” explained Conway. “It was a nice lightweight costume. Tim Rose did a lot of development on the radio control for Tic Tok. His head was radio-controlled but his hands were controlled from the inside by the performer.”

The performer in this case was required to be a contortionist. Imagine spending your day bent over with your head between your legs and your arms crossed over your chest. Then imagine walking around and trying to impart character to a little mechanical man from this position. Two men shared this demanding role, Michael Sundin and Peter Elliot. Elliot is best remembered for his portrayal of Silverbeard in Greystoke.

Elliot was not the only Greystoke cast member to find his way to Oz. The wicked witch’s henchmen, called Wheelers, are frightening creatures with wheels where their hands and feet should be. “The Wheelers were quite difficult. Their success required finding the right performers. We had speed skaters come in and they just didn’t have the strength to do it. They couldn’t keep their bodies together. So we wound up hiring quite a few of the Greystoke people. They had spent two years of their lives on all fours. Their backs were strong, their arms were strong and they did a great job,” Conway says.

“The costumes had long, extended arms with wheels instead of hands. They had handbrakes in the arms so they could stop themselves. There were slight extensions for the legs. The performers were standing sort of en pointe and the wheels were on ratchets so the wheels wouldn’t go backwards. They actually picked it up quickly, but they were people who had never roller-skated before. They had no preconceived ideas about how things should be done. They were mimes and they just got down on all fours and knew they had to support themselves.”

The Scarecrow’s head and the Cowardly Lion’s head are partially radio-controlled and partially cable-controlled. The Lion, performed by former Greystoke ape John Alexander, wiggles his ears and also moves his mouth and eyes, mostly through the magic of radio control. A radio control requires the use of a separate channel for each movement. Usually, one person handles the single control box. The same is true for cables. One person controls as many cables as he or she can. “The eyes — it is always nice to have one person control both the eye movement and upper and lower lids. It just seems to make it easier. It unifies that aspect of the face rather than spreading it too thin,” comments Conway.

The Tin Man is the only character not designed and built under Conway’s supervision. Production designer Norman Reynolds tried his hand at creature manufacturing and commissioned this particular one to be built out of tin and worn as a costume by a performer.

“Most of the screen time centers around Dorothy and this cast of mechanicals. It took over a year to build these creatures, but what we gained in that year was a dependable character and mechanism. We didn’t have any breakdowns that took more than a few minutes to fix, We also didn’t have backups for all the characters. We had several chickens, but there was only one Gump.

“One additional difficulty we had was the amount of time our characters are on screen. It is difficult to sustain the illusion or the belief in mechanical characters for long periods of time. If we had been able to incorporate the same set of “rules” for our chicken that they used in Gremlins — like no bright lights — or like E.T. - pull the blinds down to hide her — plus a relatively short amount of screen time, it would probably be an easier illusion to sustain. We are asking a lot of our audience.

“I think that an important part of any effect, not just our stuff, is that it shouldn’t scream magic at you. Audiences shouldn’t be pulled away by the technology of it all. Hopefully, they will just accept our creatures as characters in a good story,” concluded Conway.

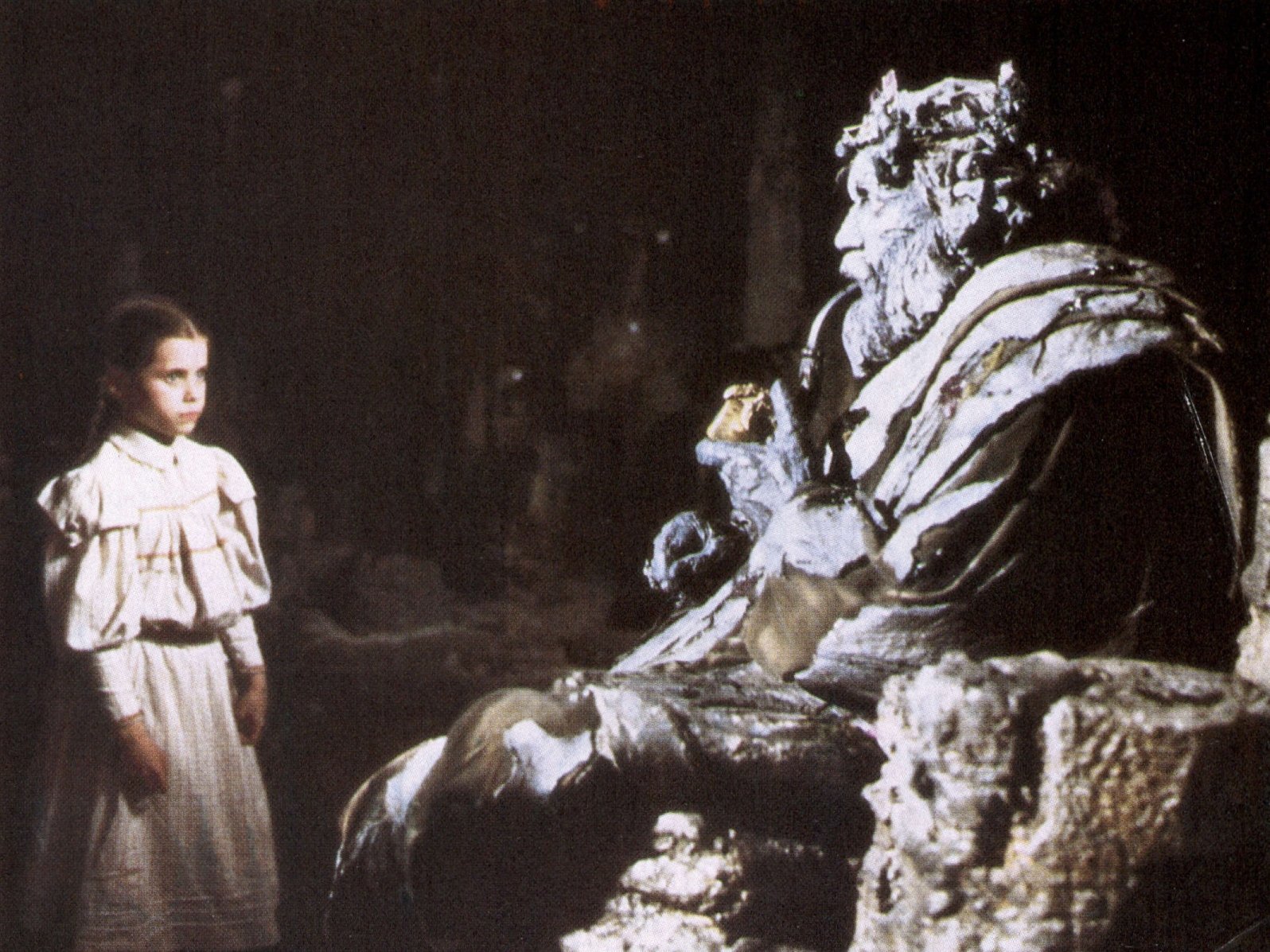

This is a film full of strange and wonderful creatures, not the least of which is the evil Nome King. He, however, was not an animatronic creature. From the beginning, he was imagined as being able to evolve into a man of sorts right from the stones and rocks that make up his kingdom. This kind of on-screen evolution called for the very specialized talents of Oscar-winner Will Vinton and his company of clay animators, who use a stop-motion process called Claymation.

“What was incredibly different about this project was the total realism that Walter wanted,” explained Vinton. “Claymation is not normally considered a realistic medium. For Oz we did not use bright colors. Everything is rock colors and we had to make special aggregates to get the textures and the scale right. In the end, it has turned out to be quite fantastic and hopefully not like anything ever seen before.

“In the beginning, however, the problem was immense. How do you make rocks move realistically? A really interesting contradiction in terms.”

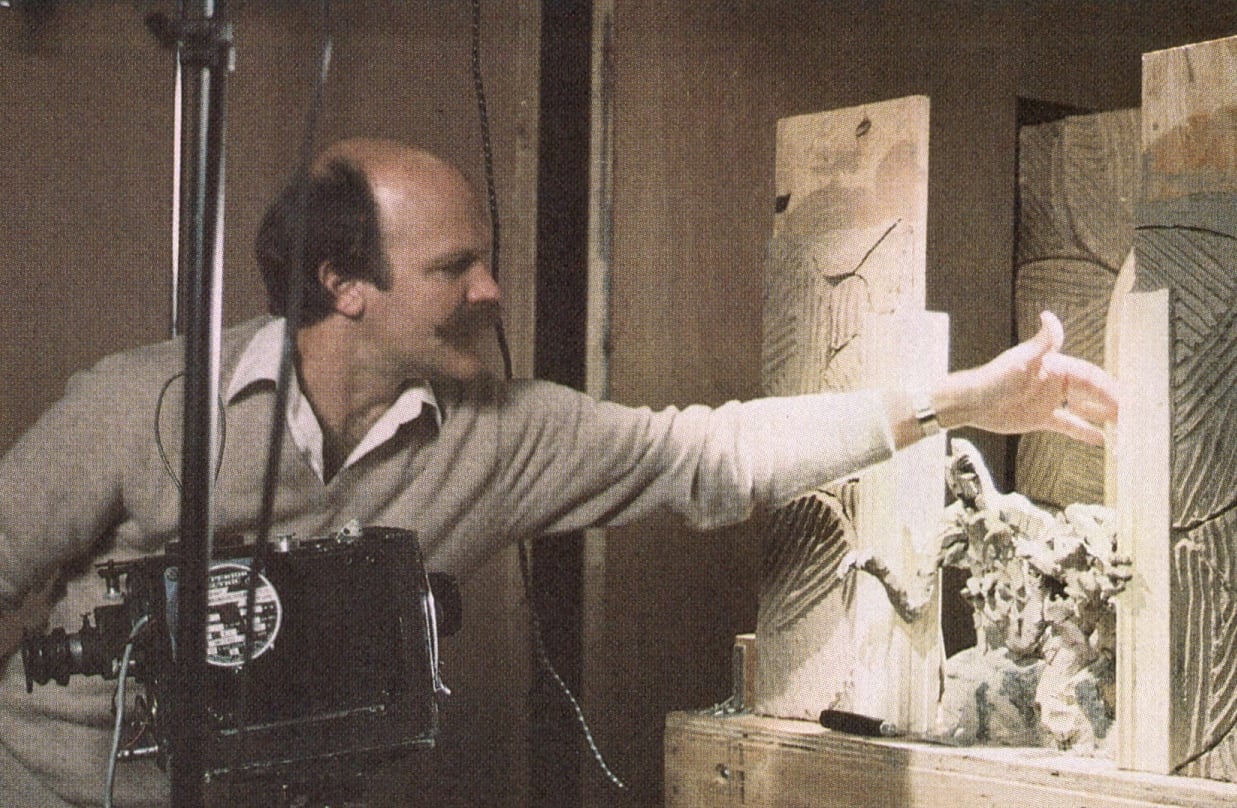

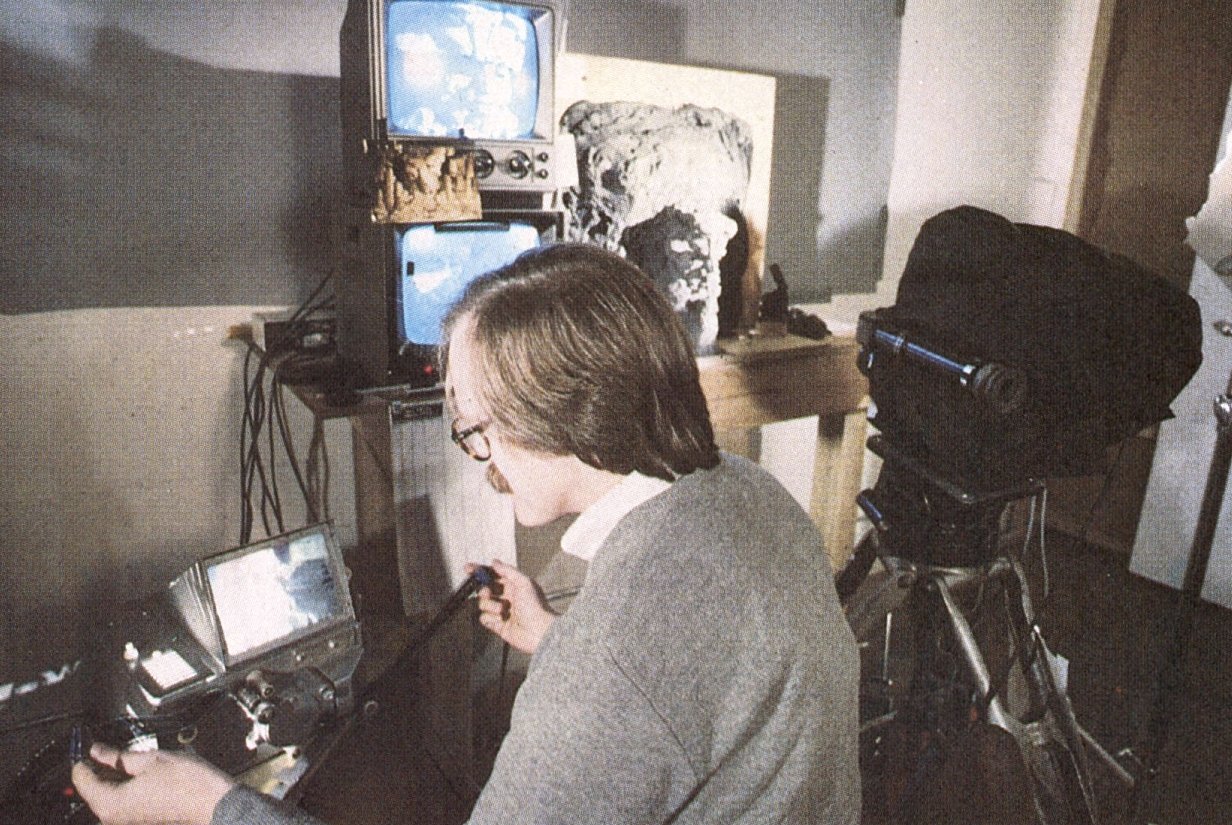

Claymation is a time-consuming process that is akin to stop-motion animation and typical model photography. Using miniature sets and specially formulated clay, the film is shot one frame at a time. Between frames sculptors/ animators resculpt the clay. “We use a motion control camera, but the heart of claymation is the totally hand-done clay sculpting of the figures one frame at a time. In Oz sometimes it’s just an eye or a hole or something that makes a face in rock move along and creep and evolve in different ways. We work off a miniature set very much as if it were miniature photography and model work except that we add a dimension. We bring the set to life within itself.”

Because of the complexities of compositing live-action and animation and of matching miniature sets to full-scale ones, Vinton employs a variety of techniques. They all start in the same place - the drawing board. “We plan really closely,” he said. “We storyboard it, of course, but the essence of planning for us is shooting reference film. For example, Nicol Williamson plays the part and the voice of the Nome King. During principal photography when the others were on the set, we would do the reverse angles of Nicol, except instead of being in costume as the Nome King, he is in a tracksuit. It looked a little outrageous when we cut it all together

“We shoot film and we shoot it tight. We shoot only the things we are concentrating on. Sometimes it’s only a face. Then we cut that in with the rest of the film to get the pacing. The reference film becomes a guide to us for expressions and obviously, lip sync.”

Vinton and his crew have taken the technique pretty far. For example, they shot an entire live-action reference film before they started their new feature-length film The Adventures of Mark Twain. “It is all black-and-white and very strange,” said Vinton. “Sometimes it’s just close-ups in a recording studio. Other times it’s actors in costume going through the motions on a soundstage. We are not limited to what the actor can do. But there are always expressions and nice nuances the actors contribute. With Oz, we would discuss the reference film and Walter would say what he did like and what he didn’t like about the performance. We would add things to it.

“Lots of times the Nomes evolve as they speak. We would discuss how it should happen. Then we write it all down on a basic animation log sheet. We have a record of the details of everything that is happening for every frame in the shot. By the time we actually shoot everything has been pretty well planned.”

Planning was vital, especially since the studios involved (Will Vinton Productions and EMI) were 5,000 miles apart. Many of the shots contained both live-action and animation elements. Many of those composites relied heavily on bi-packing, according to Vinton. “Something we don’t do too often here, but they do quite a bit in Europe, is composite one image with another in a bi-pack camera. The images we have been able to do that way don’t have quite the grain that the front-lit/back-lit shots do.” Front-lit/back-lit is a standard technique for stop-motion animation and regular model photography. However, with stop-motion or claymation the back-lit frame has to be shot right after the front-lit frame to create the matte because the movement of the sculpture cannot be precisely repeated. In model photography, this technique is combined with a motion control camera that allows the exact repetition of the entire shot to get the matte.

“Also, for shooting composites, we made some little front-screen projection alignment rigs that worked out really well. We would take a clip of a live-action plate — having registered the front projection projector with the pins in the camera so that everything was perfectly aligned — then we put the plate in the projector. This would allow us — through the camera and the video taps on it — to build sets right in front of the camera that exactly matched the plate and the live-action image. We were able to get remarkably accurate images for compositing. It was one of the crucial things, especially for bi-pack composites — to be able to get it right so that we did not have to reduce the image or shift it over.”

Conway and Vinton provided important pieces to the story of Oz, but David Watkin, the cinematographer, was responsible for a photographic frame to keep all the pieces together. Watkin is a British cinematographer complete with the English sense of humor and a Vermonter’s love of brevity and practicality. Working with a camera operator in the European tradition, he uses his talents to light the sets. His distinguished career spans 30 years and includes features including Help!, The Devils, The Three Musketeers, Yentl, and Chariots of Fire. Interviewed by telephone in his hotel room in Nairobi, Kenya where he is shooting Meryl Streep in Out of Africa, Watkin summed up his work on Oz: “I loved working on it! The fact that it was a fantasy was one of the things I loved.”

But Watkin was not the original choice for filming Return to Oz: “It started off with Freddie Francis. He was only on a short while and then he got off for some reason or another. It worked out very well because he had only done the Kansas stuff. So, it really meant there was no change in style. Freddie had been shooting about four to six weeks. I took over, I think, in April.”

Freddie Francis’ Kansas location really wasn’t Kansas anymore. It was the Salisbury plain, legendary home of Stonehenge, transformed into midwestern wheat fields. Much of the film was originally intended to be shot on location. Budget revisions brought about by Disney’s financial battles in various takeover bids altered the plans. Locations were confined to the Fondon area, and the large stages at EMI became the fantasy kingdom of Oz brought to life with the help of Watkin’s camera.

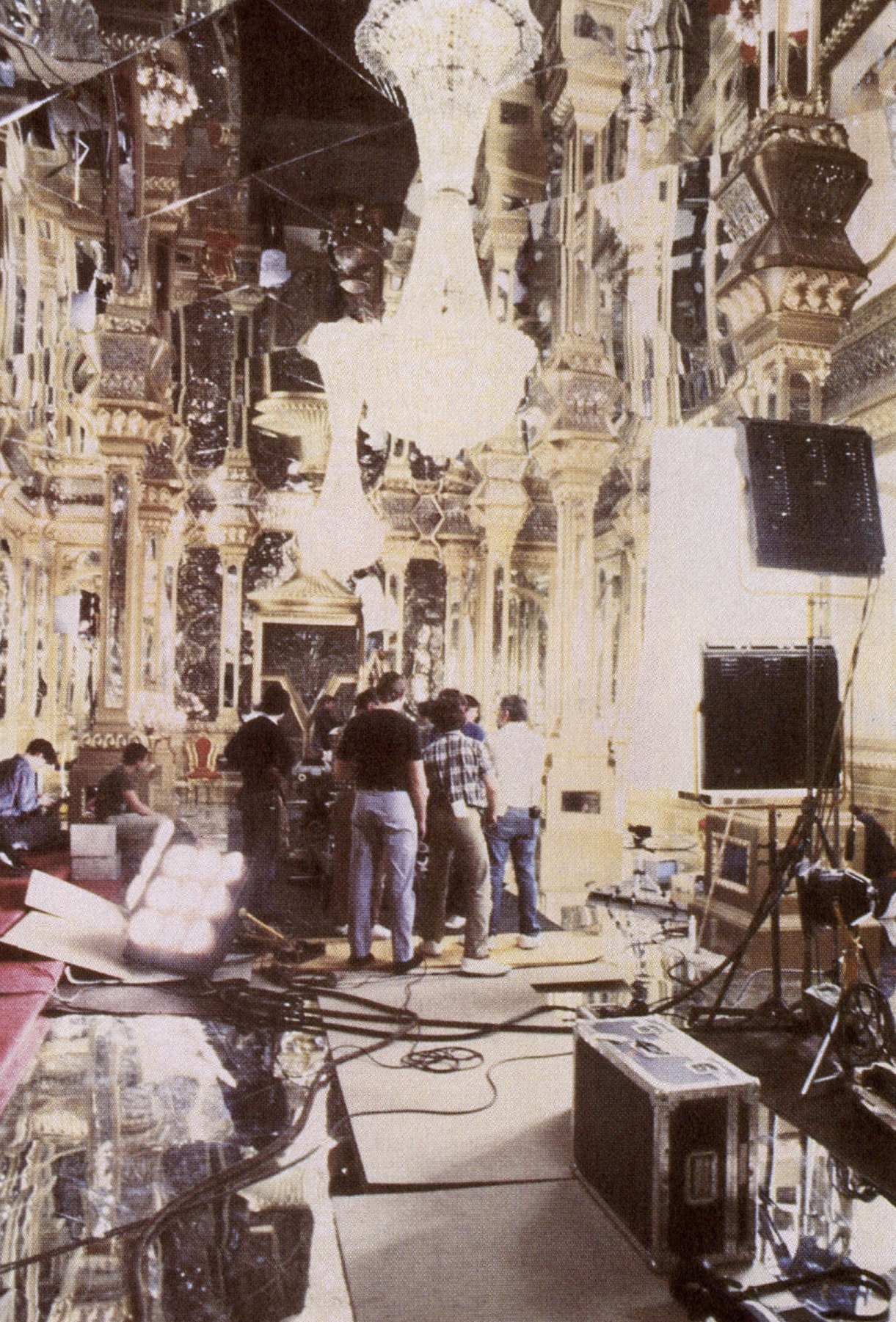

There were three main sets: Mombi’s Mirrored Palace, the Ornament room, the cave-like kingdom of the Nome King, a raging river set, and a few others. The Palace was very large, incredibly elegant and expensive. The mere description of it would make most cinematographers shudder. It was mirrored — wall-to-wall, ceiling and floor. But Watkin, by his own admission, has a strange philosophy: “I never find anything difficult. It can be interesting, but it can only be difficult if it’s impossible, and if it’s impossible it’s difficult because you can’t do it. Otherwise, it can be fun — but it’s not difficult.”

Given such an optimistic attitude, he described his solution to lighting and filming in a mirrored box in surprisingly few words. “You would think on the face of it all those mirrors would present problems - especially with all the light. In point of fact, something like that can just as easily work for you as against you. Because it was a mirrored set — floor, ceiling and walls — we did angle some of the mirrors so that we didn’t reflect the camera. We considered hiding the camera by cutting a hole in a mirror for the lens and attaching it to the front of the camera so that all that was reflected was another mirror, but we didn’t have to do that.

“What was lovely about the lighting was that the key light I used for that set was on the ground, outside the window, aiming up at the ceiling. Unless you were at a 45-degree angle to that light you would never see it. It was like having an invisible light in the ceiling. It lit the whole room and gave us a terrific advantage. I lit practically the entire set with one key light.”

“You never impose a style, the style must belong. It evolves out of the truth of anything. If what you shoot is true then it will look right.”

— David Watkin, BSC

According to Watkin, the Nome King’s throne room was perhaps the most difficult set because it was located in the heart of a mountain, where there is no logical light source. “I tried this idea of having self-illuminating stalactites. It worked all right, even though there was no clear rationale behind it. One nice thing was that Nicol Williamson began looking like Michelangelo’s ‘Moses.’ That pleased me a great deal. I don’t know if it pleased him at all.

Watkin has a philosophy about every aspect of his work. When asked about the camera, lenses and film he used, he had some unexpected comments: “The cameras I used were Arriflex BLs. The reason for that is they will accept Zeiss lenses, which are the best. To me what matters is not so much the camera but the lens. What the audience sees is the lens with the film behind it, so I always use a camera that will accept the lenses I want.

“The stock varied. I was using Kodak... actually, you’ve hit on a very sore point. Kodak had a marvelous filmstock, 5293. I shot Yentl on that. Then, for what I consider pretty unsound reasons, Kodak altered the stock to 5294. And almost everything that I liked about 93 disappeared. So I shot some 94 and some 5247. I am using the new [Agfa] XT320 stock on Out Of Africa and it is absolutely sensational. It is better than 93 was. The whole point is it’s ASA 320 and it is stunning.”

For most of the people involved with the Return to Oz, the ghost of its ever-popular predecessor was always lingering about. Early on, Lyle Conway watched a Technicolor print of The Wizard of Oz and wondered “What do we think we are doing?” But Watkin stated very matter-of-factly that he was not intimidated by the past. “It might intimidate the director, but not me. I’ve just got a job to do and it is always fun. I really like musicals, so I think it would have been nice if there were songs in it. I think it’s a pity. On the other hand, Walter may be perfectly right not having any songs in it. This isn’t a remake.

“If we had tried to do a remake, I wouldn’t have been too keen about being involved in it. I’m not a great believer in remakes. They are never as good as the original. But this is a combination of two other Frank Baum books. It is a sequel — a totally different story.”

It is not just a different story. It is a different approach to a classic fairy tale. Photographing fairy tales is not easy. Cocteau [Jean Cocteau, French poet/playwright] believed that in fairy tales realism was the key to the suspension of disbelief. Watkin’s experience on films like Yentl and Chariots of Fire probably honed his sense of realism but, he admits his efforts on Oz were not necessarily conscious.

“On any picture I am photographing there are two things I am concerned about. First is the style, which must fit that particular movie. You never impose a style, the style must belong. It evolves out of the truth of anything. If what you shoot is true then it will look right.

“In the case of a fantasy, one has a much wider range of choices that one can make because one isn’t bound by reality. Don’t misunderstand, you can’t make it absurd. It must have some element of logic. It may be a different logic but it must be a logic. However, it isn’t something I consciously plan. I think this realism or logic is something that comes naturally.” It is an integral part of the magic that transports us back to Oz.

Dorothy almost did not have the opportunity to return to Oz. The film endured more than its share of problems. The production changed cinematographers about six weeks into the schedule. The director was fired and then rehired. The whole production was shut down for a time because of budget difficulties. So when Dorothy finally does journey to meet the Gump and the Nome King this June, she will take with her the heartfelt best wishes of an impressive group of true believers: People like Francis Coppola and George Lucas, who intervened on behalf of Murch and helped him get and keep the production rolling; Murch himself, whose vision and total devotion to the project were respected by everyone involved; and people like Lyle Conway, David Watkin, and Will Vinton, whose talents are representative of the high quality of the production. It was not easy, but bringing a dream to life never is.

“Billina, I don’t think we’re in Kansas anymore.”

Access the every issue of AC and every story from more than the last 100 years with our Digital Edition + Archive subscription.