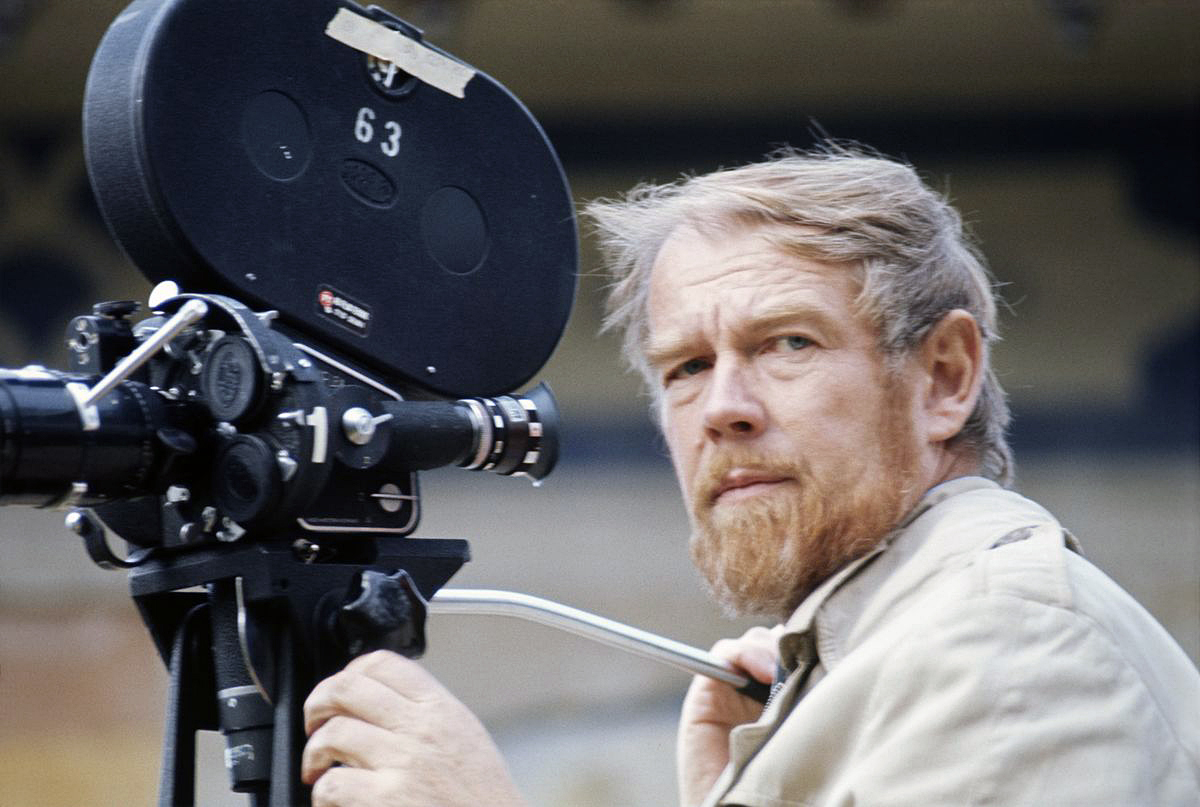

ASC Salutes Sven Nykvist

Sweden’s master cinematographer receives 1996 Lifetime Achievement Award from American Society of Cinematographers.

This article originally appeared in AC Feb. 1996. Some images are additional or alternate.

Adding yet another garland to his distinguished career behind the camera, Sven Nykvist, ASC will receive the 1996 Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Society of Cinematographers. The prize will be presented to Nykvist at the Society's annual awards banquet, to be held at the Century Plaza Hotel in Los Angeles on February 25.

Previous recipients of the accolade are ASC members Gordon Willis, Conrad Hall, Haskell Wexler, Phil Lathrop, Stanley Cortez, Charles Lang, Jr., Joe Biroc and George Folsey. Nykvist is the first non-American to earn the coveted honor.

"Sven is a talented filmmaker who has made unique and enduring contributions to the advancement of the art of cinematography," says ASC President Victor J. Kemper. "He has created an extraordinary body of memorable work that grows larger and more impressive every year. This award is meant to recognize and encourage artistic excellence and to foster an appreciation of the art of cinematography wherever movies are produced and seen."

“Every time I start a picture, on the first day it seems as if I am starting all over again. I love it. You can always learn something new. Sometimes it is about manipulating light. Other times it is about finding another angle into the human soul.”

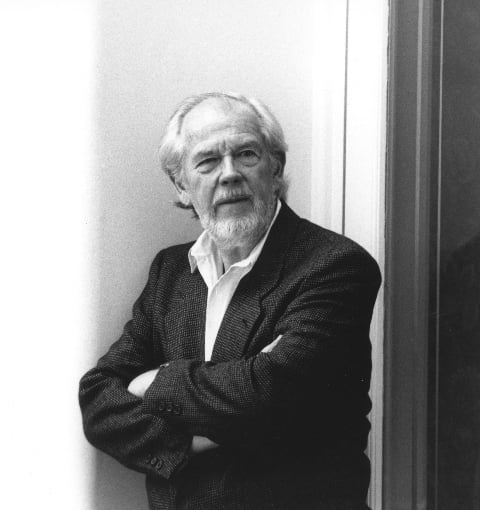

In a typically modest and understated response, Nykvist says he was "surprised but happy" when Kemper phoned him with the news. Nykvist has earned Academy Awards for his work on Cries and Whispers (1973) and Fanny and Alexander (1983), as well as a third Oscar nomination for The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1988). His body of work includes about 120 films, but he shows no signs of slowing down. Nykvist was preparing to shoot a film in Scandinavia when Kemper called, and in August will shoot a film based on a new Ingmar Bergman script.

Nykvist's name is routinely coupled with Bergman's; their brilliant collaboration stretched over much of three decades, producing such classic films as Sawdust and Tinsel (1953), The Virgin Spring (1959), Through a Glass Darkly (1961), Winter Light (1962), Persona (1966), The Hour of the Wolf (1968), The Passion of Anna (1970), Cries and Whispers (1972), The Magic Flute (1973), Scenes From a Marriage (1973), Face to Face (1976), Autumn Sonata (1978), The Serpent's Egg (1978) and Fanny and Alexander (1983).

But his duets with Bergman comprise just a small part of his life's work. Nykvist has compiled credits with many other accomplished directors, including Roman Polanski (The Tenant), Louis Malle (Pretty Baby), Paul Mazursky (Willie & Phil), Bob Fosse (Star 80), Alan Pakula (Dream Lover), Norman Jewison (Agnes of God), Philip Kaufman (The Unbearable Lightness of Being), Lasse Hallstrom (What's Eating Gilbert Grape? and Something to Talk About), Woody Allen (Another Woman, Crimes and Misdemeanors), Nora Ephron (Sleepless in Seattle) and fellow Bergman veteran Liv Ullmann (Kristin Lavransdatter). His other credits include One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, Cannery Row and With Honors. In 1991, Nykvist directed The Ox, which earned critical praise.

Nykvist's career spans half of the history of cinema; 1995 marked his 50th anniversary as a cinematographer. He shot his first narrative film, 13 Chairs, in Stockholm, Sweden in 1945, when he was 23. His subsequent body of work has played a major role in redefining the art of contemporary cinematography.

"I was fortunate to work with Ingmar, particularly at that early stage of my career," he says. "One of the things we believed was that a picture shouldn't look lit. Whenever possible, I lit with one source and avoided creating double shadows, because that pointed to the photography."

Such principles are common among modern cinematographers, but Nykvist came to these conclusions some 30 to 35 years ago, when he was blazing trails that many other cameramen would subsequently follow. He says his visual inspirations came from Bergman, and also from studying paintings at fine art galleries and museums.

"A motion picture doesn't have to look absolutely realistic," he says. "It can be beautiful and realistic at the same time. I am not interested in beautiful photography. I am interested in telling stories about human beings, how they act and why they act that way."

“There are so many ways you can use light to tell a story.”

Nykvist was born in Stockholm in 1922, the son of missionary parents who built a hospital in the Belgian Congo. A cinema buff as a youth, he later studied at the Stockholm Municipal School for Photographers. In 1941, Nykvist went to work as an assistant cameraman at Sandrews Studios in Stockholm. In those days, Swedish crews consisted of just two people — the cinematographer and the focus puller, who was also responsible for still pictures.

During the mid-1940s, Nykvist spent some time working in Italy as a focus puller, a stint that helped broaden his worldview and artistic outlook. After returning to Sweden, Nykvist began shooting film for second-unit crews. He also photographed, directed, wrote, edited and recorded sound for many documentary films. In 1952, Nykvist was the co-director, co-writer, and co-cinematographer of Under the Southern Cross, a narrative film produced in the Belgian Congo and based on an experience his parents had had with a witch doctor. At about the same time, Nykvist shot a documentary about Dr. Albert Schweitzer's work in Africa.

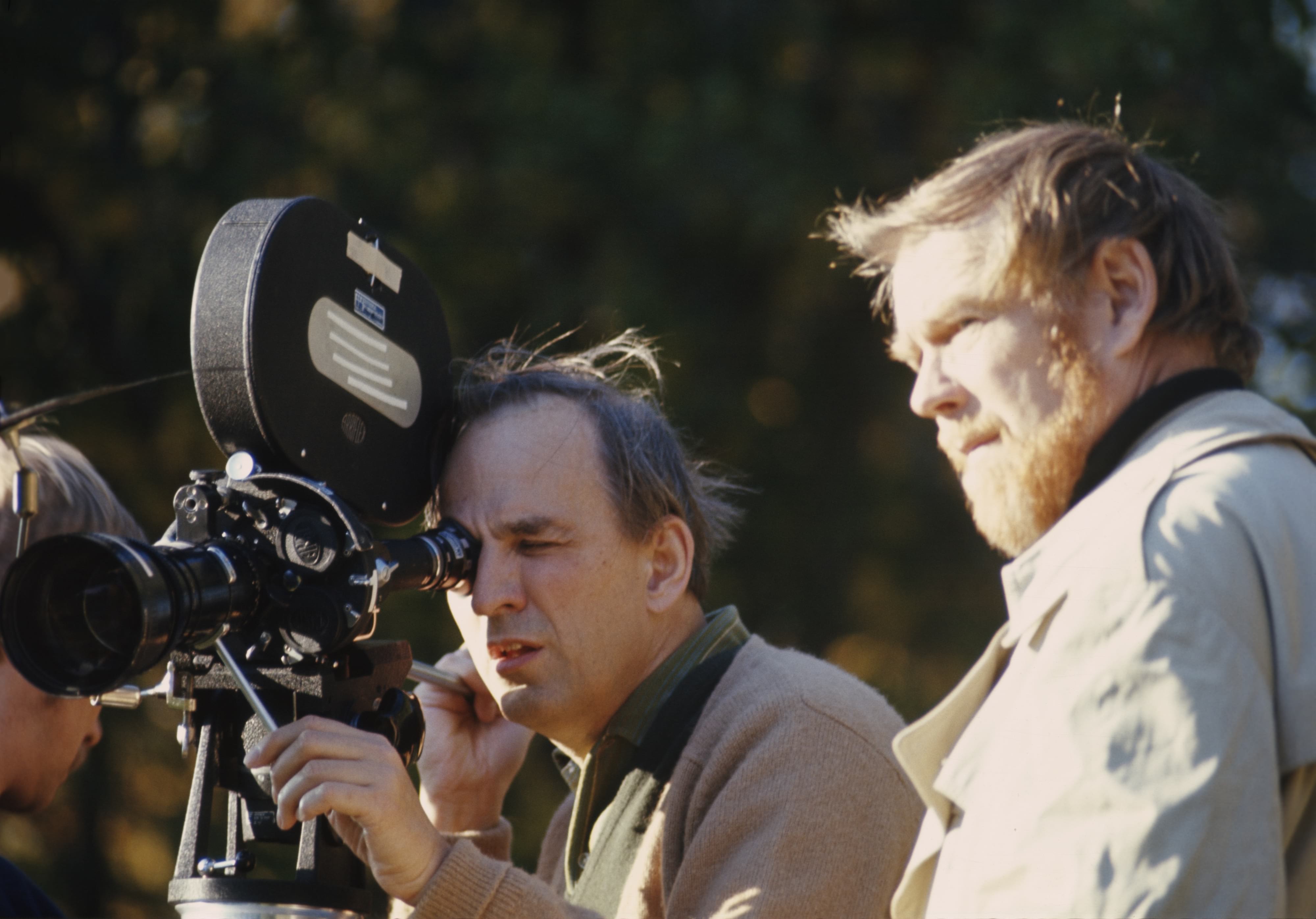

In 1953, Nykvist got his first chance to work with Bergman, as director of photography on the feature Sawdust and Tinsel (a.k.a. The Naked Night). Another cinematographer, Goran Strindberg, had been scheduled to shoot the film, but Strindberg decided instead to go to Hollywood to film a Cinemascope movie with a much bigger budget.

Nykvist recalls that during those days, Bergman was making films for $100,000 with a crew of eight to 10 people and four or five actors. "That was a very nice way to work," he says. "Everyone did everything. Everyone helped everyone else. It was like a family. Even Cries and Whispers was produced on a $300,000 to $400,000 budget. I learned so much about composition, staging and the infinite varieties of light from Ingmar."

"Every picture defines its own look, and that definition begins with the director’s intentions for the script.”

Nykvist and Bergman nurtured a natural style of visual story-telling reminiscent of silent movies, and during the beginning of their relationship, the cinematographer focused on a seminal idea. "I learned that there are types of lighting you can use to create an ambiance," he says. "There's a single sentence in The Magic Lantern [Bergman's self-penned biography] which expresses that concept: 'Light: the gentle, bare, dreamlike, living, dead, clear, misty, hot, violent, sudden, dark, spring-like, falling, straight, slanting, sensual, subdued, limited, poisonous, calming pale light. Light.'

“There are so many ways you can use light to tell a story. I think anyone who wants to understand light should read Ingmar's book."

Asked to verbally dissect Bergman's eloquent statement about the variable nature of light in layman's terms, Nykvist responds, "Gentle light is what you might use if you're photographing a woman, and you want her to look very beautiful and soft. Dreamlike light is also very soft. I achieve this with light rather than low-contrast filters, but that's just my preference. Living light has more contrast and vitality, while dead light is very flat with no shadows. Clear light is more contrasty, but not too much."

He continues, "Misty light could involve the use of smoke or fog filters. Violent light is more contrasty than living. It is a subtle distinction that influences how the audience perceives and reacts to the images on the screen. Spring-like light is a little warmer, and falling light is when the angle is very low and you get elongated shadows. Sensual light is for love scenes; it's difficult to put it into words, because film is a visual language. That's the role I play as a cinematographer — understanding the script and the director's intentions, and translating them into images that express the ideas."

Nykvist says that he generally knew what Bergman had in mind without having to parse scripts page by page. He maintains that unless the director of photography understands the artistic intentions of the director, there is no way he or she can perform the duties at hand.

"Every picture defines its own look, and that definition begins with the director's intentions for the script," he says. "Some directors have their own ideas about staging, lighting and composition. Others are mainly interested in the actors. You must be able to form a relationship with both types of directors, and also establish a feeling of trust between the cast and crew. I always tell the actors what I'm doing and why I'm doing it."

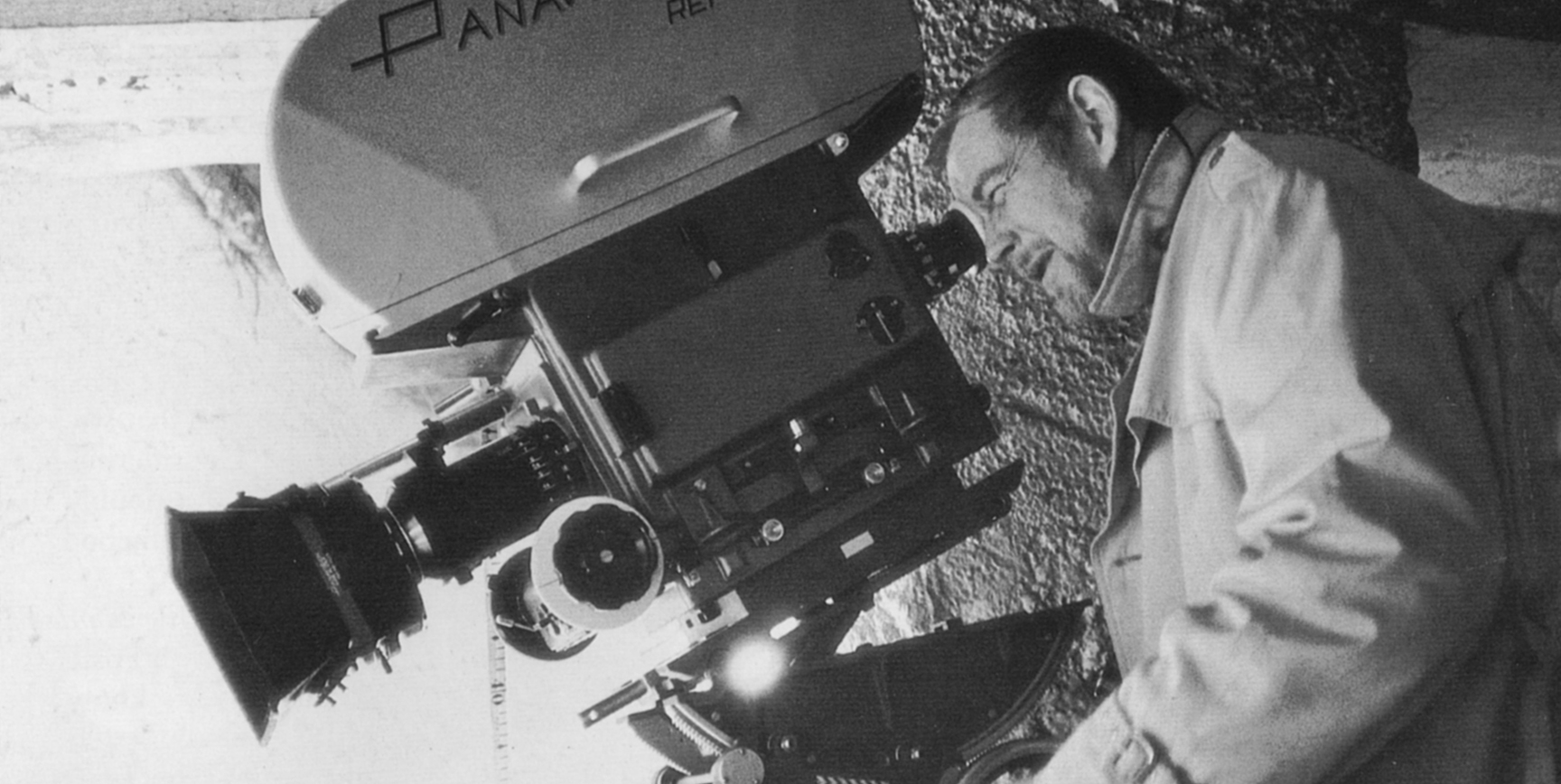

In conversation, Nykvist emphasizes simplicity and aesthetic values over imaging technology, but he is a meticulous master of the craft as well as the art. When the cinematographer was preparing to shoot The Unbearable Lightness of Being with director Philip Kaufman, the duo studied black-and-white documentary footage to determine what it had looked and felt like when the Russian army poured into Prague and crushed a civilian revolt. Nykvist replicated that chaotic atmosphere by shooting those scenes in 16mm black-and-white, which added a touch of grain. Next, he made a duplicate negative which closely matched the contrast of the actual documentary film. Woven into the fabric of the dramatic story, the footage gave the audience an emotional sense of place and time.

Every film shot by Nykvist offers subtleties that the audience feels rather than sees. In Unbearable Lightness, he used the architecture of the buildings in Prague as more than just background; they were like silent characters, standing in dignified despair as the city was violated.

“When I was working with Ingmar and Liv Ullmann, there were a few other actors who were always in his films. I can see it looking back on those movies now. I knew everything about photographing them. I learned to know their faces.”

Inevitably, though, this cinematographer's work is about faces and eyes, whether he is shooting a serious drama or more lighthearted fare. The faces of beautiful women, especially Liv Ullmann, were a central motif of many Bergman films. "Truth always lies in the character's eyes," Nykvist says. "It is very important to light so that the audience can see what's behind each character's eyes." The cinematographer notes that it takes time to really learn a face and interpret what is happening within. "That's a problem [in cinema] today," he says. "You are always working with new actors. You can't always tell immediately how their faces will take light. The truth of the characters is in the eyes; that's how the audience gets to know them as human beings. It opens up their souls. When I was working with Ingmar and Liv Ullmann, there were a few other actors who were always in his films. I can see it looking back on those movies now. I knew everything about photographing them. I learned to know their faces."

Nykvist also stresses the importance of consistency. His preference during staging is to plan for very long, six-to-eight-minute takes that won't break up the actors' performances. "Good actors will react to the lighting," he says. "When you do complex staging, you have to remember that you aren't lighting for exposure. You are creating an ambiance, and you have to figure out how you are going to get light into the actor's eyes or, when appropriate, mask them. I have no preference for hard or soft light or any other style or technique. You should use the light that's right."

He developed this mode of thinking while dealing with the challenges imposed by black-and-white photography, then applied his philosophies — most effectively — to his later color work. However, he points out that there is never one path that is suitable for everyone in all situations. He says that he tends not to concern himself with such niceties as the symbolic use of color, although there are certainly sterling examples of this strategy on his resume (e.g., the use of red in Cries and Whispers). "I worry less about being symbolic than some other cinematographers," he says. "Everyone has their own way of thinking. My tendency is to use bounce or indirect light. Harsher light can distort the story that's written on the actor's face."

Nykvist also has a tendency to use smaller lighting units whenever possible. "It feels cleaner," he says. "Smaller units give you more control. You can create more precise moods and atmospheres. This is something I learned gradually. When I shot my first feature in 1945, we used lots of lights. Sometimes I spent a whole day lighting. I wanted to shoot a beautiful picture, but every scene looked the same. Now, when I see some of my old pictures on television, I can see everything I did wrong."

Advances in imaging technology, he concedes, do provide some creative latitude, but a basic approach can often prove its value. "If you are shooting a night interior scene, there might be a lot of sources," he says. "But if you are shooting a daylight exterior, there is only one source: the sun. The question is usually how much I should fill, so it doesn't get too dark in the shadows."

Despite his 50 years as a filmmaker, Nykvist insists that every new project is a learning experience. He says that he learns from the directors, actors and crew he works with, but notes that the process is a two-way street. "If I am open to hearing and discussing their ideas, they are more likely to listen to me," he says. "That's human nature."

With all of the international boundaries that Nykvist has crossed in making movies, he has never experienced unsolvable language problems or other communication barriers. His approach to previsualizing is traditional. He reads the script, thinks about it, and develops some ideas. "I like to watch rehearsals without the camera," he says. "I watch what happens. Sometimes actors feel that they have to move when they say a particular line. You discuss this with the director and ask if he or she wants us to follow the move or track in the opposite direction. There are so many ways you can cover the same move — with tracks, or a crane — and all of them affect the pace of the action. There are always choices regarding light, movement and focal length. Those decisions come from inside."

Once the strategy has been decided, he looks through the lens and places his lights. "I put up one light and see if it feels right," he says. "Sometimes you have to say to yourself, 'I made a mistake' and try something else. There are so many different people involved in making a movie: the producer, director, art director and, of course, the cast. When you take too long to light, you can feel their eyes in your back. Everything is different every day, even your own moods. Some days everything is right. Other days everything is impossible."

Nykvist tries to reduce his approach on each picture to a few basic principles, trusting his eye and his instincts. This, he submits, is what makes cinematography such a rewarding profession. "It's an unusual occupation," he relates. "It's both an art and a craft. Every time I start a picture, on the first day it seems as if I am starting all over again. I love it. You can always learn something new. Sometimes it is about manipulating light. Other times it is about finding another angle into the human soul. That's what keeps this work so interesting. Until I find something I like better, I'll probably do this work forever."

The cinematographer died in at the age of 83 on Sept. 20, 2006. He was remembered with a special screenings series at the Camerimage Film Festival in 2022, which included a discussion tribute with ASC members Edward Lachman (who worked with Nykvist) and Charlotte Bruus Christensen.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.

Access the every issue of AC and every story from more than the last 100 years with our Digital Edition + Archive subscription.