On Location with Carnal Knowledge

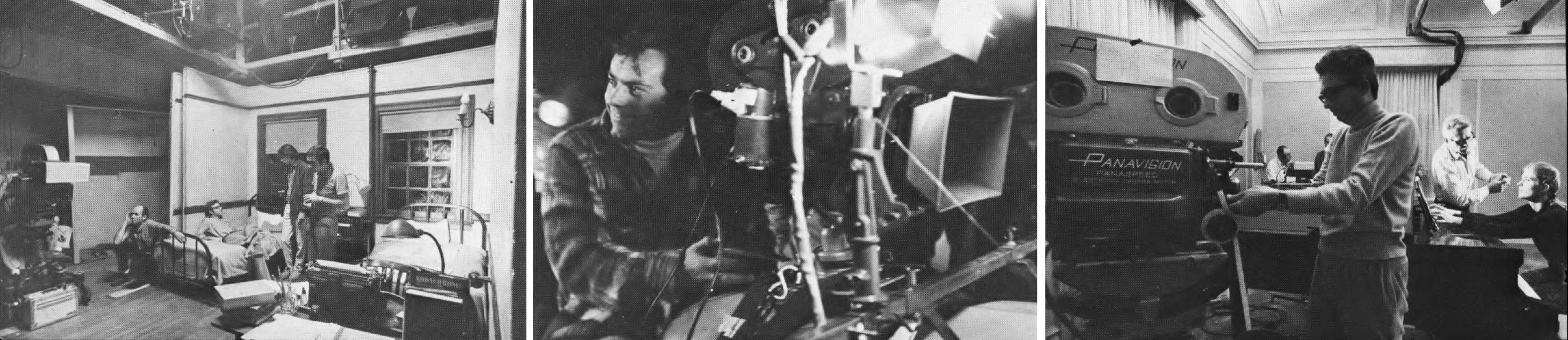

Reporting from the set of the new Mike Nichols film — a complete change of pace from Catch-22.

This article was originally published in AC Nov. 1971. Some images are additional or alternate.

Vancouver, British Columbia

For me, the excursion to this gemlike Canadian city constitutes a twofold pleasure. It is, first of all, an opportunity to observe director Mike Nichols in the process of applying his own special magic to film. Secondly, it constitutes a reunion with my good friend director of photography Giuseppe Rotunno, ASC, whom I haven't seen since I visited him on the set at Cinecitta in Rome during the filming of Stanley Kramer's Secret of Santa Vittoria.

“I was eager to work with [Mike Nichols] because I had seen all three of his films and found that he remains very close to the truth, a very important thing.”

The project under way here in Vancouver is the shooting of Mike Nichols' new picture, Carnal Knowledge, an Icarus Production from a script by Jules Feiffer for Avco-Embassy release. I am especially flattered by the invitation to come on board during shooting because the sets have been rigorously closed to the press from the onset of production — and still are. However, since I am rightly considered to be a fellow film technician rather than a journalist, I receive a warm welcome from Mike Nichols — plus carte blanche to take whatever technical photographs may be necessary to augment the excellent production shots being made by unit still photographer Toby Rankin.

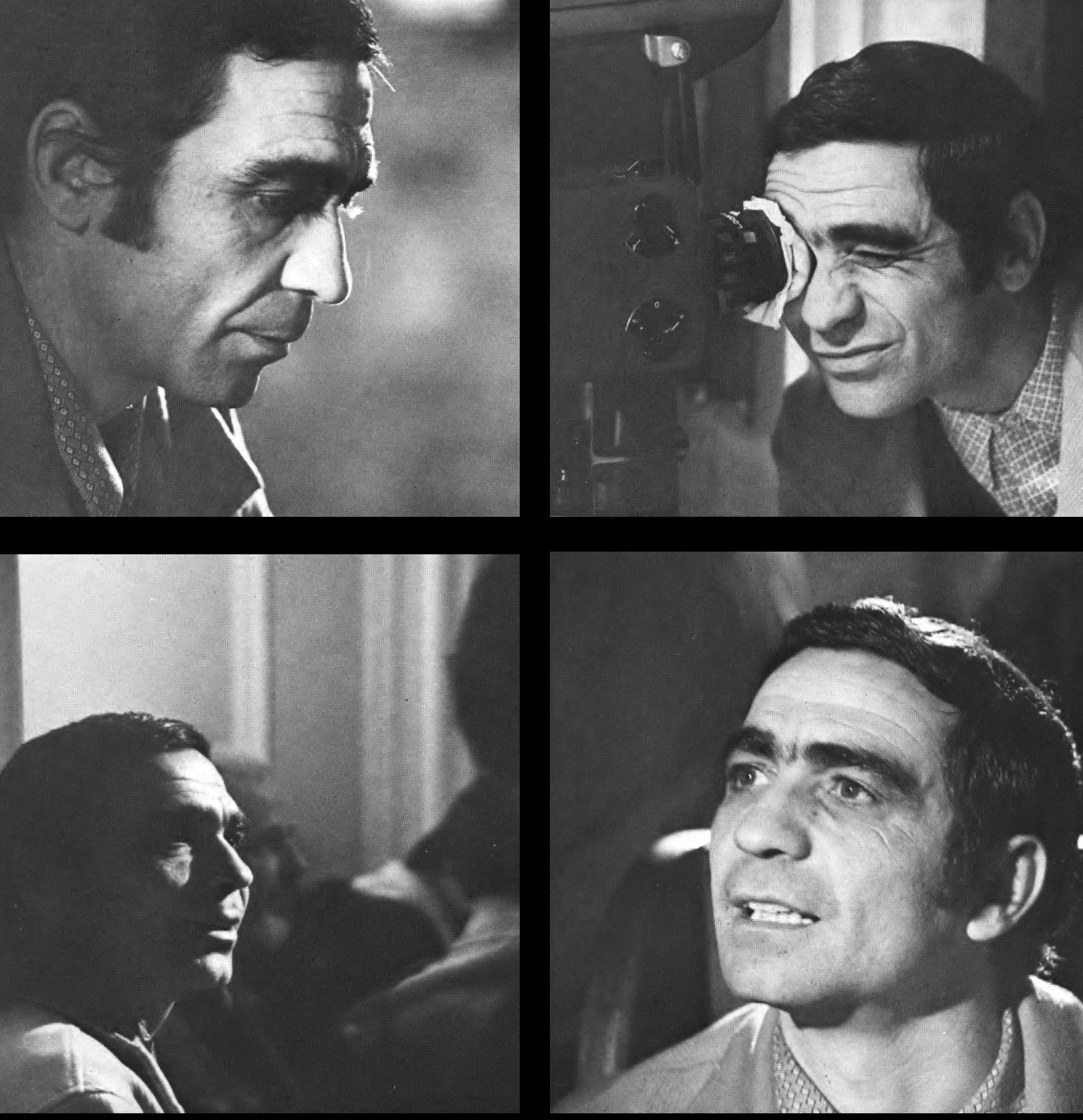

Seeing Rotunno again and watching him work is a special pleasure. Called "Peppino" by friends and crew, he is a true artist of the camera and a wonderfully warm human being, as well. Unlike the other Romans I know, who are effervescently emotional' (just like in the movies), Peppino is very quiet, almost shy, but a real tiger behind the camera. Fresh from having photographed the flamboyant Fellini Satyricon and De Sica's Sunflower, it is a distinct change of pace for him to be called upon to shoot Mike Nichols' "little picture."

Carnal Knowledge is “little” compared to Nichols' previous effort, Catch-22, which surged across the screen in spectacular sweep to the tune of $20 million dollars or so.

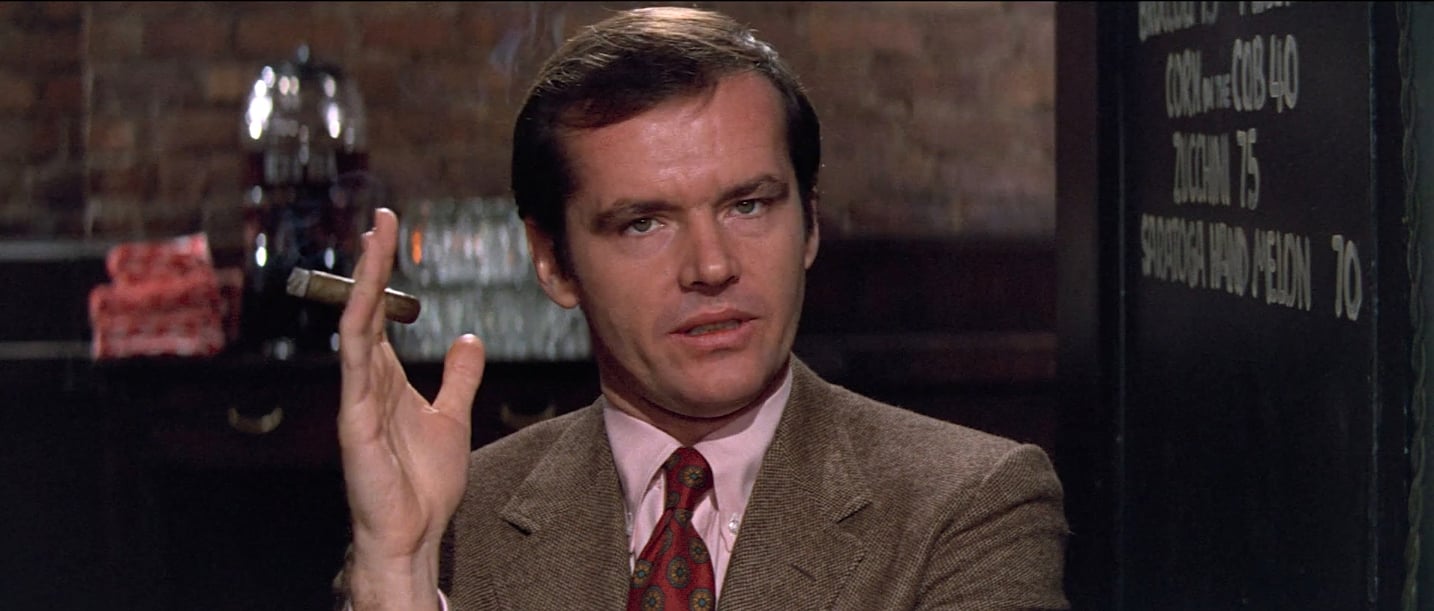

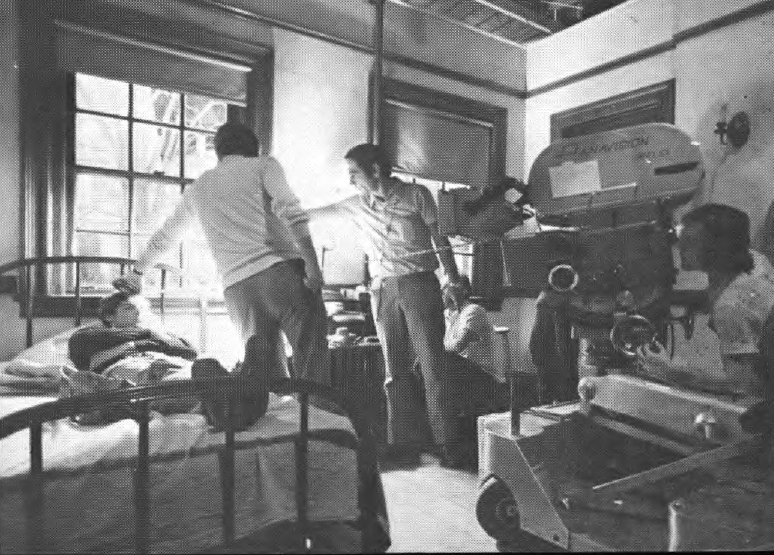

To all appearances, Carnal Knowledge is being shot as if it were a low-budget film — a minimal crew (just the people who are needed, minus the usual mass of hangers-on), very simple sets (and only a very few of those to augment the actual locations) and basically just four people in the cast. Of course, when one considers that the four people are Candice Bergen, Jack Nicholson, Ann-Margret and Art Garfunkel, this does change the economics a bit.

The crew is oddly assorted but working together in the closest harmony. Rotunno, his operator, assistant cameraman and gaffer are from Italy, of course. Other key technicians hail from Hollywood, and the rest are local people. There is a free and easy atmosphere on the sound stage, with everyone taking their cue from Mike Nichols' hang-loose attitude.

Keeping It Simple

Just now the company is shooting interiors at the Panorama Studios, a small but very well-equipped facility high on a hill in the countrylike suburbs of Vancouver. There are two small stages crammed to the walls with sets that include dormitory rooms of the Amherst/Smith type, circa 1946 — plus a typical college town beer tavern interior. The sets are almost Spartan in their simplicity.

This austere approach to design is explained to me by production designer Richard Sylbert, who has worked on all three of Nichols' previous films, winning an Academy Award in Art Direction for Who's Afraid Of Virginia Woolf?. His other credits include such impressive films as Grand Prix, Rosemary's Baby, The Illustrated Man and April Fools.

"We're trying to keep the picture very simple in the visual area," he tells me. "Since there are really only four. actors in it, other than extras, you might compare it to 'chamber music.' For this reason, we decided to stick to a few simple textures and simple colors. This is faithfully in key with the time and place — Eastern college life as it was more than 20 years ago. Such places were built of plaster, wood and brick, usually done in tan or brown or cream tones. There's no furniture in any set that isn't absolutely necessary and, so far, there is nothing on the walls in any scene. The amazing thing is that not only don't you miss these trimmings, but the austerity gives the picture a sort of 'unity of reduction'. Each film should have its own unity, and this film, in particular. It's really under total control.

"Peppino Rotunno understands this kind of thing very well. He understands that one has to get from bare wall surfaces as much as one usually gets from a lot of other things. You've got to work the walls and windows, because that's all there is — only what is absolutely necessary. A scene in a dormitory room will have one chair and two beds — that's all. There may be a few small props that belong to people but, basically, the decor is stripped down entirely. The reason is that this is not the type of picture in which you use things to make statements about the way people live — at least in the conventional sense. You're not saying: This is what I know about them. You're taking everything away, so that if a lamp is there, that lamp represents the entire period."

I remark that such simplicity is really quite difficult to utilize if one wants to put across certain subtleties and nuances and undercurrents of relationship.

"That's very true," says Sylbert. "In The Graduate, for example, it was very easy to make a visual comment about the people and the way they lived. The same thing applied to Virginia Woolf, which was a picture about intellect and the things that intellect collects. This picture is entirely different, and much more difficult. Instead of adding things, you walk into a set and begin by subtracting. It's fascinating to view the rushes and see how clean everything is, the clarity of it. After one has done a picture like Virginia Woolf, it's fun to reduce things to the bare minimum."

I observe that it's necessary to have a highly talented cameraman in order to get the most out of such a challenge. Otherwise, the result could be pedestrian, to say the least.

"You're quite right," says Sylbert, with only the trace of a shudder, "but Rotunno has been doing a really wonderful job. He has a great sense of light and what it can do on surfaces. After all, the only thing that's finally there for the light to hit is the texture — and that texture has to be developed by light. Otherwise, you can't see it. Since this picture takes place about 60% at night, the sources are also very important.

I ask him how much actual collaboration was necessary with Rotunno in order to arrive at the unified visual result. "We've tried to work together with as much preparation as possible," he tells me. "As soon as Peppino arrived from Italy, we held a series of meetings. We examined sketches that I had made and discussed the overall principle of the picture. Once we all understood what we were going for, we could begin to discuss specifics. These talks were very fruitful because, since we are working up here in Canada, we had to bring everything with us.

"It's very important for a designer to talk in depth with the cameraman, because a ski I led cameraman makes an enormous contribution to the film. What Peppino is doing may look very simple, but, in its own way, it is very difficult to do. He lights sets with complete ceilings and struggles with the surface of a wall that has absolutely nothing on it but fine texture and gets it to work in place of something very elaborate.

"He isn't doing all this because it's tough to do, but simply because it's right for this particular picture. The great thing about this film is the opportunity to eliminate all the things you've found easy to do for years, to keep pushing the surface cleaner and cleaner. The simple thing is very difficult to get right, but there's something about struggling with problems like this that makes the result very interesting."

College Is a Brown Paper Bag

I remark about the absence of color in the decor. All of the sets I see on the stages are done in the cream and tan and brown tones which Sylbert has mentioned. "It's true that there is little color," he explains, "but it's not because of a conscious avoidance of color. It's a visual way of growing from college — which I always assumed was the color of a paper bag — to the 1970s. You see people differently in 1970 from the way they looked in 1946. There is a change in contrast. Back in college, under the tans and browns and brick colors, the edge was very soft. With time, life takes on a very hard edge. The mature man wearing a black velvet suit in a white room is, in every way, drastically different from the boy he was in college, with his khaki pants and khaki room and khaki bedspreads and khaki book covers. As the emotional pressures of the film's story increase, the contrast — which was soft and delicate in the beginning — will harden up. This is the effect that Peppino will be striving for, also, as shooting progresses."

We speak, then of concepts of filmmaking and of how theories and abstractions are made to come alive in real terms on the screen. It becomes clear to me that Sylbert, for all his quiet and relaxed mien, is a very "together" sort of technician, one who leaves nothing to chance in achieving a desired cinematic effect.

"There is no excuse for a picture to be ugly, even if you are talking about ugliness," he tells me. "In my opinion, ugliness is the inability to control something. I also feel that there's no excuse for a screen image that isn't well thought out. After all, that is what we are here for. But the only real security anybody has when it comes to these elements is the director. I began my work in film with Elia Kazan [A Face in The Crowd, Splendor in The Grass] and then did three or four pictures with Sidney Lumet in New York. This is my fourth picture with Mike Nichols.

"The story takes place in three different time periods. It begins in 1946. Then there is another part that happens in 1961, and the final part develops in 1970. We are trying to make the three sections of the film look different, in order to show the passage of time. But we are also trying to keep everything very simple, which means that the differences must come from the way that we use the light."

"Over the years I have been concerned, first, with the material, and, secondly, with the quality of intelligence of the people involved. After all, it's just as hard to do a terrible film as it is to do a fine one. There's just as much work involved in putting up a terrible set as there is in doing a good one. The way to eliminate such concerns is to work with directors like Kazan and Nichols who, in themselves, guarantee against such things. They're not going to do a picture that's a waste of time. That's why I say that it's always the director that matters to me.

"There is also the matter of personal relationship and mutual respect — which is a big thing to me. After the four pictures that Mike and I have done together, there is a journalism that comes into it — a kind of shorthand. When you've lived with someone professionally for months on end (we were on Catch-22 together for a year and a half), you can set your mind at ease and say to yourself: 'This is the kind of man I not only like personally, but he will guarantee that I won't have to worry about making a bad picture.' With such confidence in a director, I don't even have to read the script to find out whether I like the idea of the picture. I know I'm going to like it simply because he's doing it."

Though highly individualistic, Sylbert is heavily imbued with the true professional's awareness that effective filmmaking is very much a team effort. This comes out very clearly in his comments about rapport between the production designer and the director of photography. "It's very close, and we talk all the time." he says. "You must keep in constant touch and help each other to get certain effects. Nothing matters except the picture itself and the final result requires that everyone stick together until it's on the film. It's not: 'I put up this beautiful room and he didn't shoot it right.' That's a lot of baloney, and there's no excuse for it. Rotunno feels the same way. If he's after a certain effect and I can help him get it, I'm only too happy to do so."

On the sound stage they are preparing to shoot a sequence in the tavern set. All of the practical fixtures are faced with amber glass, so Rotunno quite logically suggests that the set (and the actors) be illuminated exclusively with amber light. This is, from the technical standpoint, a very bold gesture and one that requires the utmost care in execution, lest the actors all end up looking as if they've got jaundice. However, Nichols likes the idea and soon the entire set takes on a golden glow.

The extremely low ceiling makes it, at best, a very difficult set to light. Rotunno's gaffer, Rudolfo Bramucci, solves the general illumination problem by hiding tiny Mole-Richardson Nook lights behind the beams.

Meanwhile, the make-up artist and the hair stylist are struggling to make Candice Bergen· look plain — something like the girl-next-door — but it is obvious that they are fighting a losing battle. They remove almost all other make-up, draw her hair back severely and (in a last desperate attempt to ugly her up) spray her classic features with artificial sweat. She's completely game, but nothing works. She still looks ravishingly beautiful.

In reference, apparently, to some private joke, Nichols keeps calling her "Bugs" and she responds with a most un-movie-starish good humor. Between setups Peppino introduces me to the lady, explaining that I am the editor of the ASC journal. Innocently he asks her if she knows what “ASC" stands for.

"Of course," she replies. "My father's a member of it."

And so he is. Famed comedian Edgar Bergen has been an Associate Member of the Society for many years. At a recent ASC dinner meeting he convulsed the crowd by remarking: "My daughter, Candice, thinks I'm pretty square. She says that if I ever took LSD I'd probably see Lawrence Welk."

Very Close to the Truth

My first chance to talk to Rotunno about his work on this film comes when the company breaks for lunch during my first day on the set. Heretofore, I am told, the Panorama Studios had boasted no on-the-spot feeding facilities, which is rather unusual for a studio so isolated from restaurants and such — but Nichols, believing that a well-fed crew is a happy crew is an efficient crew, asked that a commissary be built behind the stages. It was fitted together from three "mobile home" type modules, equipped with the latest kitchen gadgetry, and serves a menu any gourmet restaurant might well be proud of.

While we are chomping on our pheasant under glass, I ask Peppino how this assignment with Nichols came about. "Mike Nichols had somebody in charge contact me while he was in Rome and we had our first meeting," he explains. "Then he began to write to me about this picture. I was eager to work with him, because I had seen all three of his films and found that he remains very close to the truth, a very important thing. Then, six months ago, I flew to Los Angeles to talk with him. It could be only for a few hours, because I was on another job. It was then that he asked me to photograph this picture."

I ask him what he considers to be the special challenges of photographing Carnal Knowledge and he replies: "The story takes place in three different time periods. It begins in 1946. Then there is another part that happens in 1961, and the final part develops in 1970. We are trying to make the three sections of the film look different, in order to show the passage of time. But we are also trying to keep everything very simple, which means that the differences must come from the way that we use the light."

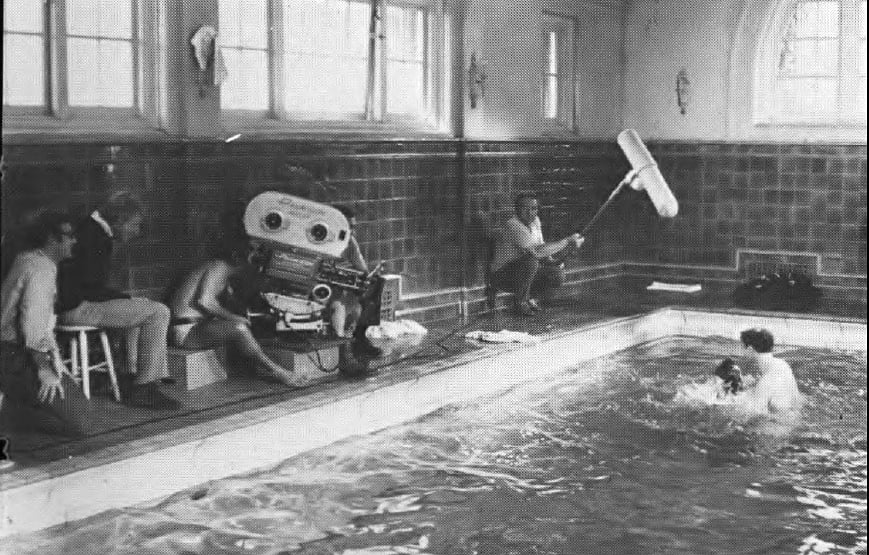

Rotunno tells me that shooting in the studio is a rarity on this picture, because most of the filming is being done in actual locales. "We have been shooting inside many real buildings," he tells me. "We have shot sequences inside college buildings, dormitories, sorority houses, locker room, libraries — all kinds of places. In locations like this we use mostly small quartz lamps for lighting. We build on the stage only the rooms we cannot find in real buildings, but they are built in the same way, with low ceilings and everything – very real, very true."

I remark upon his daring in using amber light in the sequence I have just watched being filmed, and he comments: "It seemed real for that sequence and Mike Nichols liked the idea — so we did it. But I don't use colored light very much — only when it is really needed, like in Fellini Satyricon."

I mention the fact that Leon Shamroy, ASC, (whom I know is something of an idol to Rotunno) is famous for his precise use of colored light. Peppino's face becomes radiant at the mention of the name. "Ah, Leon," he says. "I will never forget Leon. He is truly in my heart. I worked with him as an assistant on Prince of Foxes in Italy. I was very young and he was very kind to me. I learned so many things from him about this job. He is a great cameraman — and a great man. I think that is even more important."

Like all professional cinematographers, Rotunno considers light to be the basic, plastic building material of the cinematic image, but he does not indulge in any high-flown theories about it. "All you really have is three things: the key light, the fill light and the back light," he observes, "but you can do so much with those three, get so many different combinations — just like a kaleidoscope."

I mention to Peppino my conversation with Sylbert and he says: "I am working very closely with him. We talk together and help each other. We are always looking for the fastest way, but the best way, to do something, because now the costs on a· picture are· very important. You do not have time for experimenting. It takes so many people to make one movie. It is very easy for each person to go off on his own separate road, but if you work together you can create something beautiful, something that is very right for the picture. We are very happy in our work on this one, and I think it will show up on the film."

Access the every issue of AC and every story from more than the last 100 years with our Digital Edition + Archive subscription.