Chasing the Wind: Twister

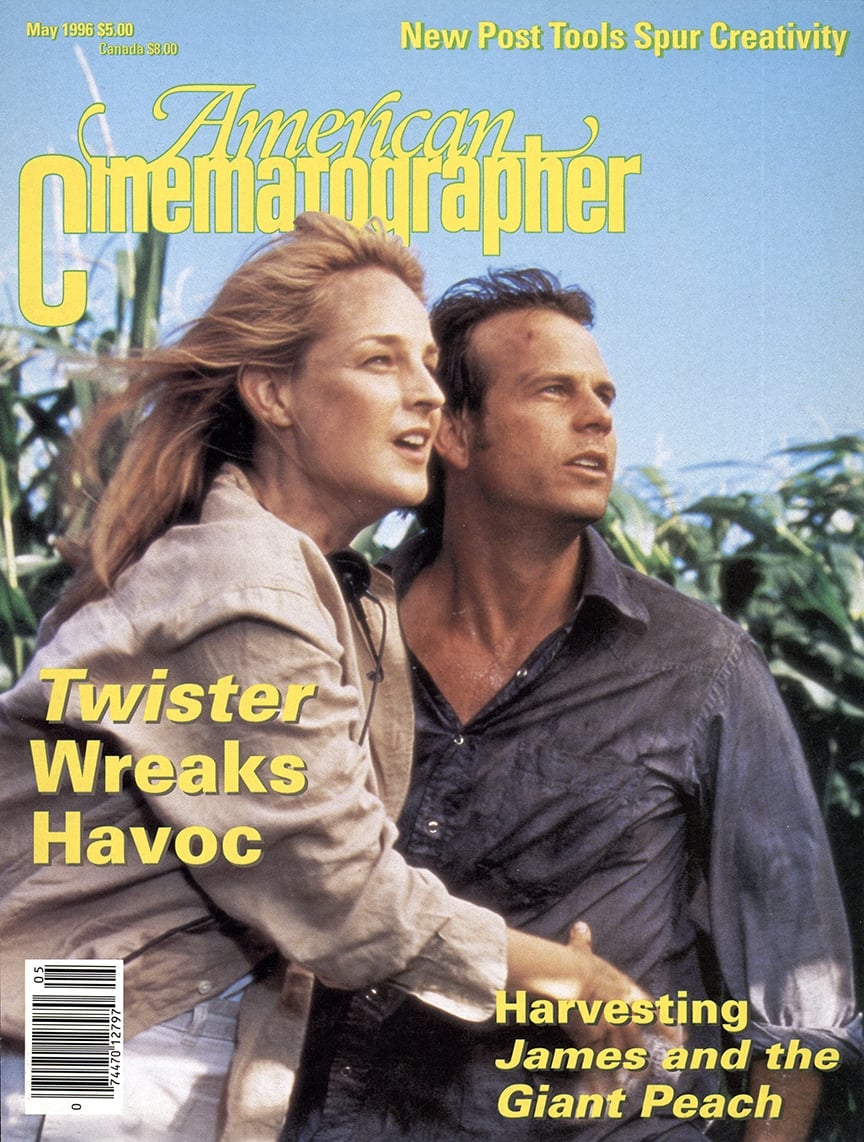

Director Jan de Bont, ASC and cinematographer Jack N. Green, ASC track malevolent forces of nature.

Twister is an action-adventure story about an unusual breed of meteorologists who behave more like Indiana Jones than TV weathermen.

The story (written by Michael Crichton) may be fiction, but these people really do exist. Known as "storm chasers," they run the gamut from serious scientists to thrill-seeking maniacs.

The first storm-chaser was probably Dorman Newman, who lived in England during the reign of Charles II. Newman left one of the earliest detailed accounts of severe weather in his “Narrative" of the winter storms that hit the British Isles, Holland and France in 1662. “Histories," Newman said, “are the best explainers of such WhirleWinds, being taken from observations..."

During the turbulence of 1662, 500 trees were blown down in Essex Park and there was great concern over the resulting “bad Vintage" and “scarcity of wine" in France. A woman daring to cross London Bridge “had her Coats blown about her ears... and was exposed to the view and laughter of wiser people." A man in Cambridgeshire was “lifted up into the ayr, and sported with as a feather, then set down upon the ground, upright on his feet to the wonder and amazement of himself and spectators."

Even today, with all of our satellites and high technology, human investigators remain the most reliable means of collecting information on a tornado strike (or "twister") and its aftermath. For that reason, real-life “chasers" play a vital role in the ongoing effort to understand and predict twisters. They also act as a human early-warning system, tearing through open country and relaying storm updates by radio and cell phone.

The depth of this obsession can be surprising; many storm chasers develop curious attachments to their quarry, treating tornados as if they are sentient beings with personalities. One real-life chaser gave up her job and moved 13,000 miles to live in Guam, the better to hunt typhoons. If one misses her, she tells people the storm “jilted" her.

Other tornado aficionados sometimes grouse that a storm isn't “mean" enough, an odd complaint when you realize that a “mean one" packs the punch of a one-megaton nuclear blast.

The wildest of the storm chasers, though, would have to be "core punchers," people who deliberately drive into the heart of a thunderhead where a tornado can lie hidden — a potentially fatal undertaking.

Such adventurers communicate on the Internet and have their own newsletter, Stormtrack. Close to 600 foul-weather fans subscribe; even if half are armchair storm chasers, that leaves roughly 300 real chasers, both professional and “recreational."

Twister aspires to give viewers both visceral thrills and some insights into these adventuresome souls. Teaming up to help realize this goal were director Jan de Bont, ASC and cinematographer Jack N. Green, ASC.

Green joined the largely location-shot production in Iowa after “a lot of really bad weather" had already been endured by the film's crew and original director of photography. "I was grateful for that," Green admits. “They'd really had to sweat out a lot of weather problems and delays and even some script problems. All of that had largely been cleared up by the time I got there. I came in after the first 5½ weeks of shooting and continued on for the last 12. I believe that they had started location shooting in April [of 1995,] which is the height of the rainy season. On many occasions, production vehicles got stuck in mud bogs and had to be towed out by big rigs. All of those unpredictable circumstances made things very difficult on everyone."

Green is best known for his work on many Clint Eastwood features, earning an Oscar nomination for their bleak Western Unforgiven and an ASC Award nomination for last year's The Bridges of Madison County (see AC August 1995). Twister marks Green's first teaming with de Bont, who debuted as a director on the action blockbuster Speed after directing the photography on such hits as Basic Instinct, The Hunt for Red October and Die Hard.

“Jan is a very good director, and, like Clint Eastwood, he prefers to move fast. On Twister, we had to move fast just because we had so many cameras to set up for each shot.”

— Jack N. Green, ASC

"Twister is about a group of scientists who have invented an instrument pack they hope to insert into a tornado," de Bont explains. “They want to use the information gathered to develop a whole new warning system." But the group is not alone. Another team of scientists, with more funding but less honor, tries to beat them to the punch.

“The scientists are extremely competitive," de Bont continues. “It's like whoever gets there first wins the Nobel Prize. There's personal and economic gain at stake: grants, renewal of labs, major contributions to their university, a lot of things. There's a lot riding on this because it is a breakthrough that will save lives."

Like the stormchasers they were dramatizing, the film's crew members were constantly on the move. "Jan is a very good director," Green says, “and, like Clint Eastwood, he prefers to move fast. On Twister, we had to move fast just because we had so many cameras to set up for each shot."

In addition to struggling with cameras, heavy equipment and fierce mechanical special effects, allowances had to be made for computer-generated opticals. “Jan and I both knew that some of the imagery we were filming was going to be enhanced and altered by digital effects later on," Green says.

Effects specialists from Industrial Light and Magic were on the set to make certain the exposed footage would accommodate the computer graphics de Bont had planned. “Whenever we set up any shot that was going to include CG," Green says, “we'd get together and talk. It didn't require exposure changes or special filters or anything like that. We'd arrange the composition to allow room for the tornado or for trucks tumbling through the sky or for houses blowing apart. We were never doing the show 'alone' — there were always the as-yet unseen digital effects to be taken into account."

Surprisingly, no computer-controlled camera movements or lock-down shots were made during first-unit scenes destined for CG additions. Everything was done “wild," even the handheld shots. Certainly, Green notes, composition and framing were planned in close collaboration with ILM, but once those allowances were made, "the CG effects would accommodate our movements. That allowed us a lot more freedom and ILM gave us terrific cooperation."

Particularly careful planning was required before filming a handheld shot in a car, during which a CG tornado would ultimately be seen through the windows. "Imagine how difficult it is to make the tornado fit the moving landscape and a jostling handheld image," Green explains. "Working with ILM was great because they wanted to make their system fit us; they didn't want to change our style of photography."

Smaller scenes had their own set of frustrations. Most day exteriors were supposed to take place under stormy skies. But the weather in Oklahoma and Iowa in the middle of summer was dazzlingly clear.

Green had faced a similar situation when he filmed the rainy climax of The Bridges of Madison County. Although he had always intended to use artificial rain in that scene, Green had hoped for at least one afternoon of natural overcast. He never got it. Instead, the scene was shot at dusk over three consecutive nights; the foreground lights were constantly dimmed to balance the actors' faces against the slowly darkening background.

On Twister, however, Green did the opposite. "We built up the light on the actors' faces," he says. "We didn't shoot at dusk. There was brilliant sunlight all around, so we put a lot of light on the actors to balance them with the sunny background. Then, the entire image would be brought down and darkened, either by stopping down during filming or later during printing. That, along with all the wind machine and rain machine effects, made it look as if the characters were really in stormy weather. Occasionally, we could build an overhang or some kind of shadow rig, but not very often.

"Thank goodness there are dramatic differences in lighting near a tornado, something I found out by looking at actual storm footage," he adds. "You can be in dark clouds in one spot and have bright sun 150 yards away. So I'm hoping the audience might forgive us whenever the light on the actors might be brighter than you'd think a boiling tornado would provide."

This factor became especially important when the filmmakers were shooting the actors inside cars which were supposed to be driving through storms, even though the actual conditions were sunny and clear. "Remember," Green points out, "you're carrying this bright background, but dark and cloudy CG images are going to appear in that background. So I had to light the actors up brightly; once the entire image is underexposed, everything looks properly dark and dank.

"For example," he continues, "if f16 is the exposure outside in the sun, I'd set the stop at f22. Inside the car, I'd light the actors at f11, making them two stops under. Outside, it's one stop under. Then you print down, and hope that the CG effects will cover up any efforts you might have made to stretch the audience's imagination."

The balancing act forced Green to pour light onto the performers during many day exteriors. For close-ups and two-shots, a 12K HMI "set fairly close" would provide most of the lighting. "I'd always throw something over it to soften and fill in the shadows," He says. "That way, we wouldn't have to worry about the shadows dropping off into pitch black when the whole image was brought down. And we'd do whatever we could to keep the actors comfortable."

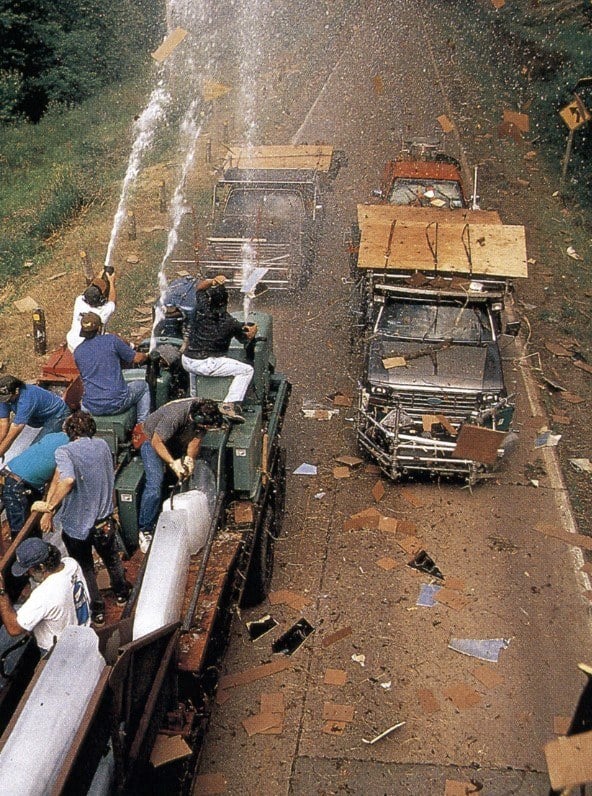

There was never any attempt to project raindrop patterns onto faces. "We didn't have to," Green says. "We put live rain or live hail on the actors, and later mixed in some CG hail. We had tons of ice and big ice-chippers mounted on trucks to do traveling hail shots. There were also huge jet engines mounted on truck-trailers providing high-velocity wind to blow trees over and flatten stalks of corn. We had to take incredible precautions because we were shooting that stuff car-to-car."

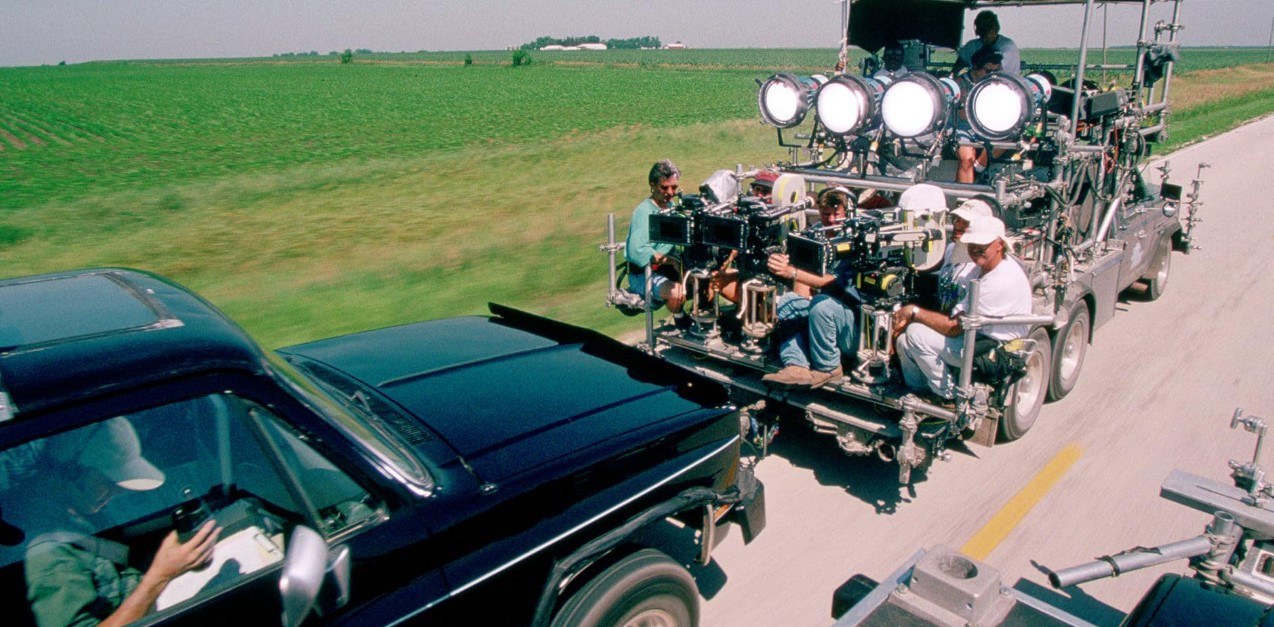

The setups could get impossibly complicated. Imagine a semi hauling a jet engine driving alongside another semi hauling an ice-chipper and gas-powered wind machine, all leading an insert car carrying four cameras, which is towing a car with the actors inside.

"We had four or five cameras rolling on that kind of thing, sometimes more," Green sighs. "Sometimes we'd even have more than one camera vehicle. There could be a pickup truck in front of the actors' vehicle with two cameras for wide and tight shots. At the same time, we'd have an insert car driving parallel to the actors with three cameras in it, filming one medium shot and two close-ups. We'd start up a convoy of all those vehicles and it could take a half-mile before everything was up to speed. Then we'd start the ice. And then the debris. I can't tell you how frustrating it would get because of the sheer number of things that could go wrong!

"In addition, you have to provide protection for the people on the insert cars, what with all that wind and debris. There were shelters on the insert cars for the operators and assistants; they also wore helmets and protective gear. But we found that if we built great big shelter structures, none of the ice and debris would get to the car we were filming! We had to learn just how big to build the shelters through trial and error. I remember boxes full of helmets and eye shields, and often people would be harnessed into the insert cars.

"So there was a lot to do before we could expose a single frame — first, the safety setup; then, the live special-effects rigging; then the lighting; and finally the cameras. It got to be really tedious."

The production used commercial roads; five miles might be shut down, with a detour put in. Sometimes, it would require two or three takes to get a shot, and moving everything back into position might eat up an hour. "That's why the first take had to be good," Green says. "Of course, with five cameras rolling most of the time, you had a good chance at it. We had a good ratio of nabbing solid first takes."

The film's logistical difficulties caused a variety of other technical challenges as well. For example, recording dialogue with jet engines blasting away at the actors was just about impossible. "Any lines spoken during the storm sequences had to be recorded as nothing more than a guide track," Green says. "And many times, you couldn't hear any voices at all on the guide track. There was plenty of ADR work after the show, re-recording everything. It was really the toughest environment I've ever had to try and be creative in.

The film's unique visual requirements called for some clever camerawork, and in many ways dictated the very style of Twister. "In shots where there was wind and rain, we mounted [spinning-glass] rain deflectors on the cameras, but we didn't have to put a water deflector on the Steadicam. The operator waterproofed the system as best he could, then put on hearing protection, a poncho, a helmet, and did the scene.

"We had an enormous amount of Steadicam, some handheld, and tracking or dollying only when we absolutely had to. When you're running people through a man-made storm with winds of 50 or 60 m.p.h., you just can't use a Steadicam. But most of the time, we could make the Steadicam work under whatever conditions we were filming in.

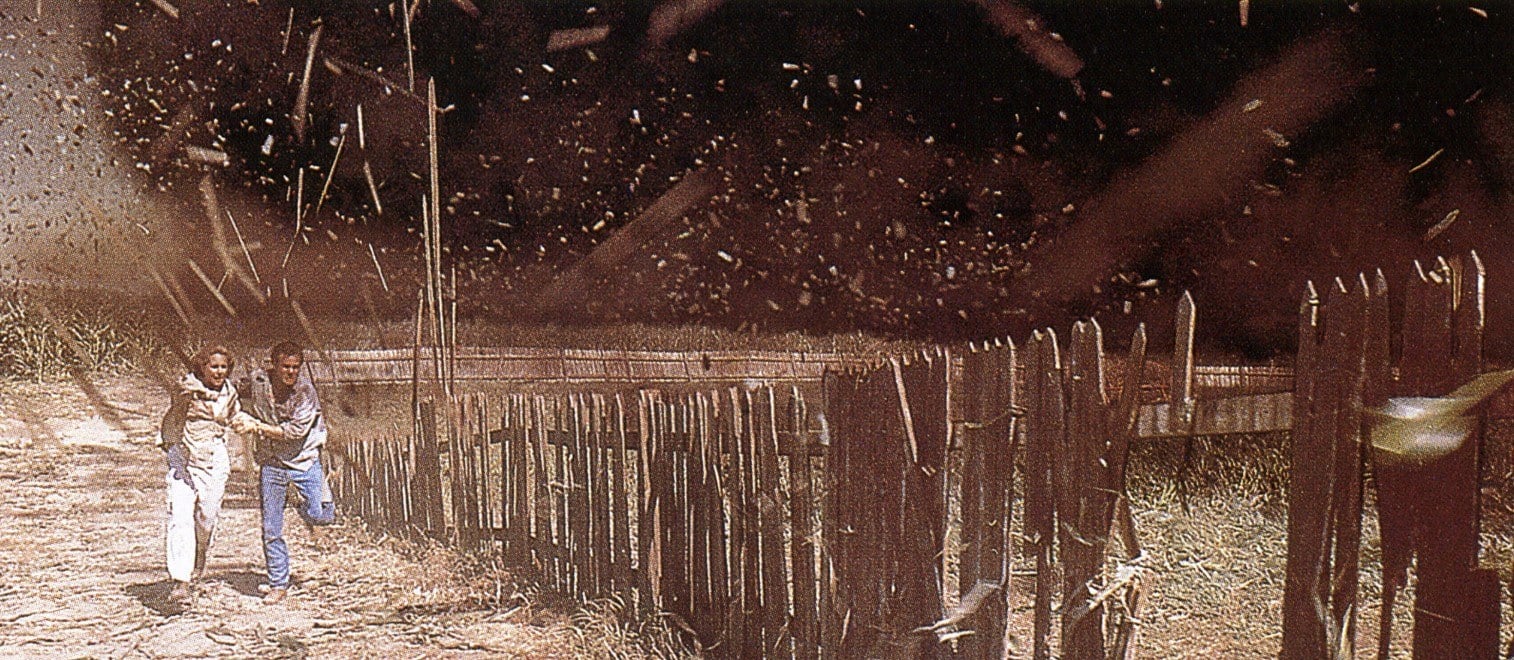

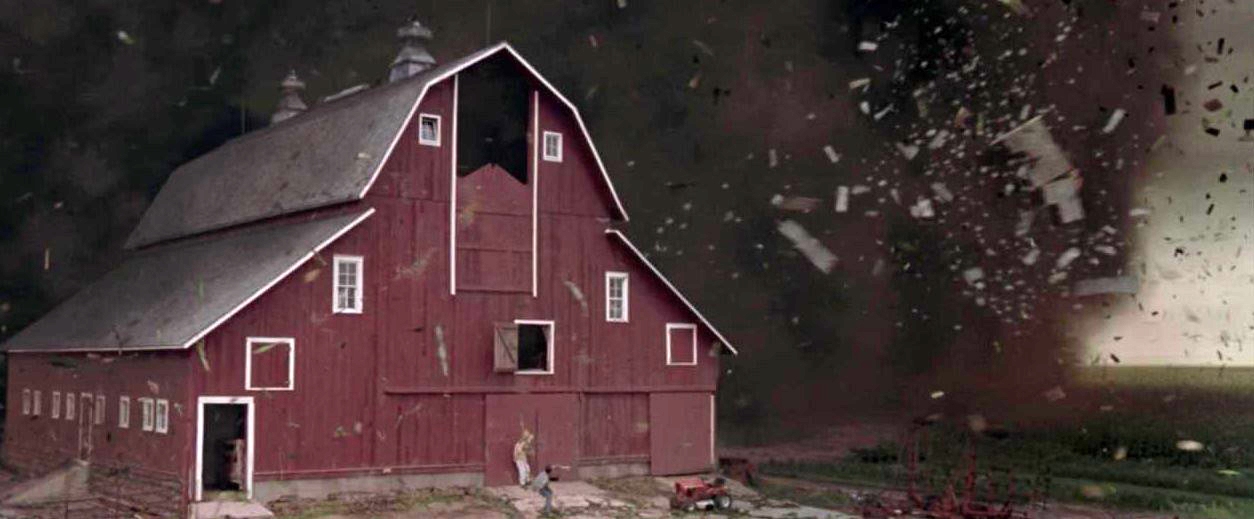

"I can't remember many shots where we weren't running at least five cameras. During one sequence in which large farm buildings are wiped out by the storm, we ran 13 cameras! On a shot in which a gasoline truck explodes, we had between 11 and 13 cameras, including Eyemos and high-speed cameras."

The cinematographer deployed Panavision cameras, both Platinums and Golds, throughout the shoot. "We had some Arriflexes for high speed work, and locked-off Eyemos to get close shots of action without endangering people," he says. "As far as lenses go, we had three sets of Panavision anamorphic lenses. Even if we were just doing a scene with two people talking, we still had five cameras running because of all the live special effects."

With so many cameras rolling, the Green team was cranking out between 10,000 and 20,000 feet of footage each day. "We printed just about everything," he points out, "which made dailies two or three hours long! I'd spot-check every day, but it was just too tedious to spend all that time viewing everything."

Because of the CG work, that footage would go through many generations. To provide the finest grain possible, Green chose 5245 for the day exteriors. 5293 was used for day interiors and night scenes, while night exteriors were filmed on 5298.

One particularly interesting night sequence tracks the film's heroes as they travel through a town that has been devastated by a tornado. Recalls Green, "We used a real city, but it was something of a ghost town, so we built additional store and home facades and added a few things to make it look as if it had been active and alive. We had Musco lights and construction emergency lighting units mounted on trailers. We also had two of those emergency units and lit a couple of small areas with them. We added all kinds of flashlights, moving lights, blinking ambulance lights, and car headlights — any kind of source we could think of to make the lighting seem as real as possible."

Another key night scene takes place inside a farmhouse that has been nearly destroyed. There were no practical sources other than a fire engine and similar emergency lights, but all these were located outside the house. Green lit the exterior with a Musco, but inside, the only practicals were flashlights.

"The farmhouse interior was done on a set built in an old airplane hangar in Oklahoma," Green says. "We had a couple of little lights pointing into the set through the windows to light up a few areas. The source of that light was supposed to be the emergency lights, along with some light from ambulances. Then we added the flashlights held by the actors, which actually served as our main sources."

When location interiors were filmed, rain and wind machines were constantly hammering on the outside walls. "I don't know if there was a wind machine left in Hollywood," Green says. "We had six gasoline-driven wind machines, three or four electric wind machines, and those two huge jet engines mounted on flatbeds. It was just incredible, trying to imitate what those storms do."

"I've always been enormously intrigued by rough weather," de Bont says. "Lightning, hurricanes and tornados are the most powerful things that happen on this world. And tornados are so random in their destruction. They're also incredible to look at, beautiful and devastating at the same time — like in The Wizard of Oz. When you look at that tornado, you get mesmerized by it. When I first saw it, I thought it was real."

Both Green and DeBont wanted to give the tornado in their film a living malevolence. As Green says, "It's almost as if it's luring the chasers into a situation where it can kill them. People who chase storms actually feel that tornados have personalities."

To capitalize on this idea, de Bont treated the twister like an actor playing the heavy. "It starts out in the early stages as being a little more magical than deadly," de Bont says. "But very quickly, you find out it's nothing to fool around with; it's a big monster, as big as a mile in diameter, that comes from the sky."

The full power of the tornado is shown in the film's dramatic climax. Green relates, "Our heroes can't escape by truck and they are running away from the funnel. They're chased through some of the most incredible live special effects that I've seen in my entire life. The enemy becomes buildings and fences that are torn up and thrown at them."

Although Green was frustrated by clear weather most of the time, there were two occasions when real tornados made sudden appearances on location. "We had very strict rules about where we could be," Green recalls. "If a tornado was imminent, or if lightning was within a mile and a half of us, we had to get under cover — which prevented us from turning the cameras on those two tornados and cranking. But we were able to get some good footage of real funnel clouds that didn't touch ground. You find yourself in this incredible rain where it's hard to breathe; there's just so much water in the air."

"There was a second unit filming as much of the real thing as possible," de Bont notes, "but they had to keep their distance; a twister can have a forward speed of 60 miles an hour."

On those occasions when a tornado had to be duplicated by ILM, things got very complex. "The tornado is a character," de Bont explains. "You have to direct it and you have to be very specific. Where is it going, what exactly is it going to do, where's the dust going to be, how much debris should we see, how much forward speed should it have? It's very much like directing an actor, really."

Asked if he's ever been caught by a storm in real life, Green thinks for a moment and smiles. "Come to think of it, I've had more than my fair share of severe weather experiences — all during shoots! Years ago, I was filming a feature in Hawaii and got caught in a hurricane. I was caught in another one in Acapulco when I was doing a commercial for a cruise line. And when I was a camera operator on Tex, a tornado touched down within four or five miles of us while we were shooting an exterior. On Twister, one touched down not too far away from us during exterior shooting," he adds. "I guess that's a good amount of storm experience. But I've always been smart enough to avoid that kind of thing on my time off."

Green was honored with the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award in 2009.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.