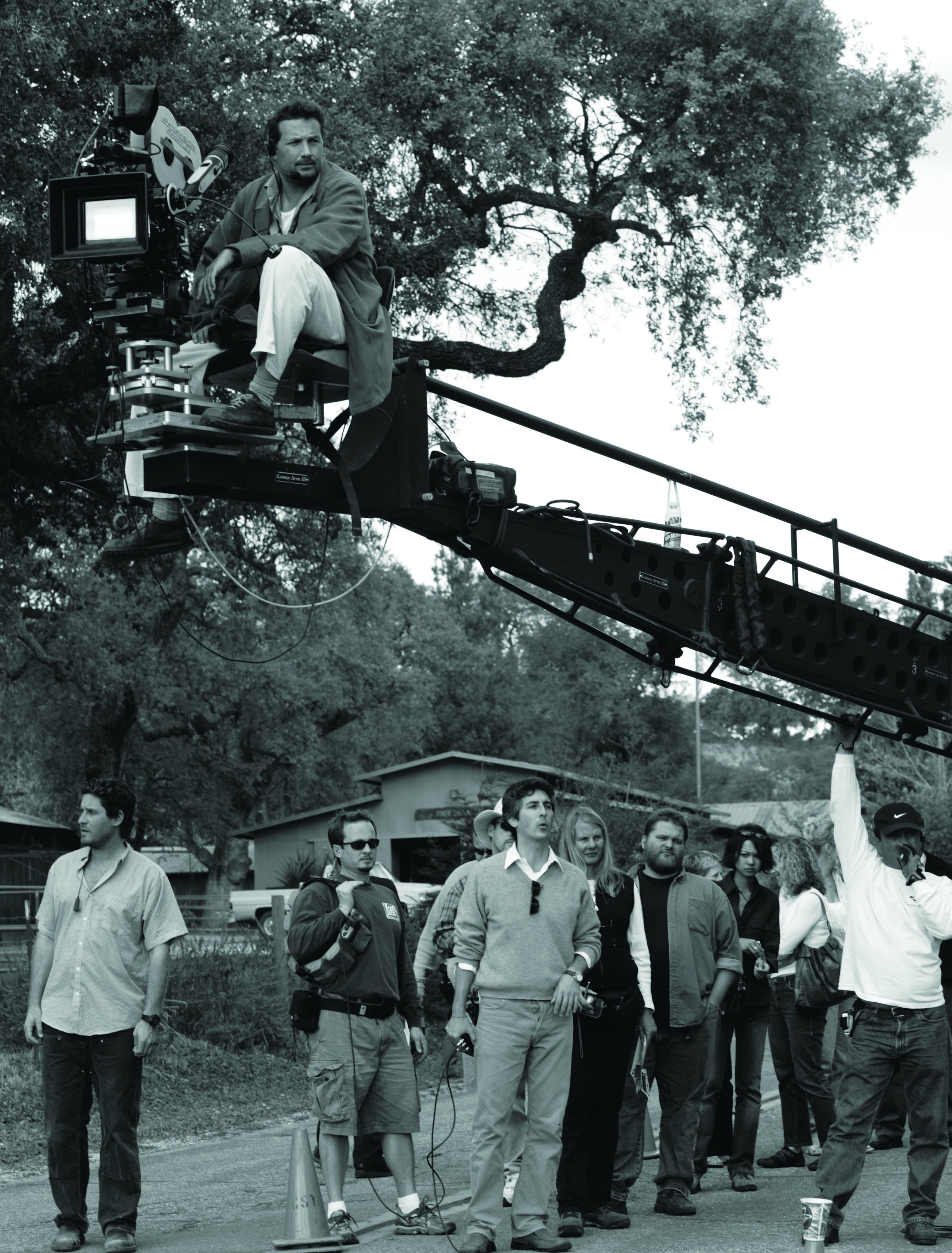

Cinematic Instincts: Phedon Papamichael, ASC, GSC

The cinematographer shares his views on capturing memorable images for movies.

Phedon Papamichael, ASC, GSC was operating the camera toward the end of shooting James Mangold’s western 3:10 to Yuma (AC Oct. ’07) when he found one of his cinematographic “moments.” Murderous outlaw Ben Wade (Russell Crowe) is calmly sketching in his notebook as Dan Evans (Christian Bale) anxiously awaits the train that is to take Wade to Yuma Prison. Gunmen are lined up outside, waiting for a shootout. In a soft voice, Wade tells Evans a story about how one day, when he was 8 years old, his mother gave him a Bible to read and then left him, never to return. Childhood trauma marked his entire life.

As he finishes his story, Wade tilts his head up slightly, and his eyes shift from his sketch to Evans. It was at this moment that Papamichael was pushing in on Crowe’s face using a 3' slider. “I realized, while operating, as the camera slowly pushes in from a medium close-up to an extreme close-up, the subtlety of his performance — just a minimal approach to the most emotional moment of his character in the film,” Papamichael says. “To the naked eye, it appeared Russell was almost doing nothing, but when we were watching it in the final edit of the movie, it was just the right amount for the size of the close-up. It is a perfect example of a film actor doing just the right performance for the big screen.”

A Passion for Spontaneity

Papamichael likes “happy accidents” on set — a facial expression, a glance or a subtle movement by an actor that has not been rehearsed but comes instinctively. “You know when it happens when you get lucky,” he says. “It is not something you can design. One has to feel when to push in — you really need to be submerged in the words and have that dictate the push-in speed. Having a great actor helps you ‘read’ it! That is what cinema is about: finding those moments, these little gems that they give us filmmakers.”

Papamichael has sought those moments throughout his career and has simultaneously striven to partner with directors who share his passion for spontaneity. Watching with the patient eye of the still photographer — which he also is — and making actors feel they are in safe hands is the approach that has come to define his cinematography: an attentiveness to performance that puts him right next to the director in the creative process without imposing a recognizable personal style on the film. “I don’t want people to see a movie and say, ‘That is a Phedon Papamichael movie.’ I want to adjust the tone to where the director’s comfort zone is. The greatest attribute of a DP is to find what is in the director’s head.”

From Cassavetes to Corman

Born in Greece and educated in Germany, Papamichael graduated with a degree in fine arts. From there he went to New York, where his father, a painter and art director, was working with John Cassavetes on the director’s penultimate film, Love Streams. It was a formational time for Papamichael, as he was about to start a career as a cinematographer. “I am coming from Cassavetes, where the camera is a slave to the actor,” he says.

After moving to Los Angeles, he started shooting for Roger Corman, the founder of New World Pictures, who launched the careers of many actors and filmmakers. The movies were low-budget shockers involving vampires or murders at strip clubs, with titles like Stripped to Kill II: Live Girls and Dance of the Damned, but Corman got them theatrically released, and they were a way in for aspiring filmmakers. “We shot them in 15 days — all on 35mm with an Arri BL2 — in a former lumber yard on Main Street in Venice,” says Papamichael. At Corman’s studio, he befriended AFI graduates (and future Academy Award winners) Janusz Kamiński, Mauro Fiore and Wally Pfister, who were also starting their careers and embarking on a trajectory toward ASC membership.

Striving for Subtlety

Papamichael shot seven movies for Corman over two years, all in a highly stylized way, but the cinematographer’s instincts pushed him toward a simpler approach. He wanted to be a more “classical” cinematographer and was inspired by the work of Robby Müller, NSC, BVK and Néstor Almendros, ASC, AFC and their preferences for using natural light. “I was never a very aggressive ‘painter of light.’ I always looked first for what the natural light was. I don’t like to over-light, and I don’t like strong backlight.”

He puts emphasis on composition and looks for camera moves that are subtle. His philosophies ultimately paid dividends, as he worked with directors such as Diane Keaton (Unstrung Heroes), Wim Wenders (The Million Dollar Hotel), Brad Silberling (Moonlight Mile) and Gabriele Muccino (The Pursuit of Happyness) — and he ultimately found three filmmakers whose working style most closely matched the way he liked to shoot: James Mangold, Alexander Payne and George Clooney. “We grew up in the same generation, and we’re all inspired by French New Wave, Japanese cinema, Italian neorealism, ‘classic American filmmaking,’” Papamichael says. “All three of these directors are very reactive and instinctive. Their films are not really storyboarded; it’s all about the actors’ performances, the close-ups, the little moments on actors’ faces that we try to capture.”

Eyes Wide Open

“Phedon really believes there is something magical that happens on set, and one’s eyes must be open to what is happening in front of you,” says Mangold, who has directed six films with Papamichael as cinematographer. “It is not only your intellectual ideas that matter; you have to be aligned with what is around you — faces and so on. There are so many things I love about Phedon. He has always been my first choice; he is like a brother to me. When we are watching something on a monitor, I find us leaning towards the same things. It’s not like I have to point it out to him.”

Papamichael echoes this sentiment. “Jim and I are very much in sync about composition, it’s crazy. I’ll say something to the operator over the headset, like ‘tilt up and pan a bit left,’ and Jim, without having heard me, will echo the exact same note.”

“Phedon brings an eye to performance and a sense of composition,” says Mangold. “He is always awake to the fact that we are not just executing a plan from a few months ago, but that something can happen today. We have a lot of conversations in abstract about goals, but I always feel like in the first week the movie tells us what it wants to be. Given the shorthand between us, we can see what our movie is going to be as opposed to what we wanted it to be. And what is good about our relationship is I don’t have to convince him of it — we both see it. When those moments happen, they teach you how to handle tomorrow’s work.”

Mangold notes that the fact Papamichael also directs movies affects his cinematographic approach. Says the director, “We agree on the need to keep moving, keep cooking!”

Capturing the Unexpected

Mangold says he and Papamichael have been “very intentional to move between different movies so we don’t get stale.” Be it the music of Johnny Cash (Walk the Line; AC Dec. ’05), a cowboy movie (3:10 to Yuma) or a Raiders of the Lost Ark sequel — Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny — they have always looked to capture the unexpected.

On Ford v Ferrari (AC Nov. ’19), Mangold was determined to make the audience feel what it was like to drive a race car at high speeds — but even then, he and Papamichael were improvising. “The last scene where Christian Bale crashes and dies? “We had to wing that,” says Papamichael. It was their last day of shooting on that racetrack, and the sun was about to set. “We had only about 10 minutes of sun left. We were in a camera car and at the same time on the radio telling the hero car how to overtake us and pull away to disappear below the horizon line. No rehearsal. We had no second chance, because the sun was going fast.”

Earlier in the film, Henry Ford II (Tracy Letts) is taken out for a test drive. “We just put Tracy in a pod-car and took him for a crazy ride and he started crying with real emotions,” says Papamichael. “We were all thinking, ‘Oh, my god, that’s incredible!’”

First Impressions

Papamichael gets his initial impression of a movie from the screenplay before he talks to anyone about it. “Movies are made three times: in the writing, the shooting and the editing. If there’s a fundamental problem in the writing, you cannot shoot around it because it will confront you again in the editing. Alexander [Payne] is very precise with his screenplays, and that helps define the shooting style.”

After the script comes the prep. Before they shot the 2013 feature Nebraska, Papamichael drove with Payne from Billings, Mont., to Lincoln, Neb., in Payne’s mother’s old Honda — not to scout, but just to get a sense of the land. “I had been in the U.S. for decades, but I found towns in the Midwest to be different from towns in Europe. We were three days on the road in September, it was nice and sunny, but we would drive through towns and nobody would be on the streets. I asked, ‘Where are all the people?’ Alexander said, ‘They are probably inside, watching TV.’

Nebraska

“Nebraska is all about loneliness — social isolation,” Papamichael continues. “That’s why wide frames and shooting in black-and-white was appropriate. Alexander says, ‘I want the banality of things.’ So, I shouldn’t apply cinematographic beauty to this because it is also partly about the ugly sides of humans. Nebraska is stylized in a certain way; it aims for the simplicity of the characters, not overpowering visuals.

“With [lead actor] Bruce Dern, a lot of it is wide because it is about his body language and these landscapes. A close-up can be very powerful, but not if it is used all the time. If I am wide all the time and then I go to a close-up — for example, when Woody [Dern] is sitting on the sidewalk talking to his son after being humiliated by Ed [Stacy Keach] — it is very moving because it is one of very few extreme close-ups.

“Often, our wide frames become a function of humor,” Papamichael adds. “In one scene, Woody and a group of old men are watching television. They don’t take their eyes off the screen as they speak their minimal dialogue. That frame got a laugh from audiences before anything was said. I like when the audience is given time to explore a single frame. I prefer that over fast editorial pacing.”

Helping the Actor

When working with actors, Papamichael says, the most important thing is that “you have to make them feel safe on set — then you get their performance.”

Noting the trust Dern had in the filmmakers on Nebraska, the cinematographer adds, “Bruce would ask, ‘What do you want me to do?’ Payne would say, ‘Do your thing and we will find what we want.’ It could be a little bow of the head in disappointment and a little look up — but how would you find that in preproduction?”

Papamichael’s preference for operating helps him catch these little gestures he might otherwise not see. “I make different decisions when I am operating,” he says. “We want to take advantage of all these gifts, these gems they give us — we have to find them.

“Actors have a very close relationship with the operator,” he continues. “Bruce told me he remembers every name of the operators he’s worked with — more than the DPs. When you have finished a shot, the first person the actor sees is the operator. The actor will give you a little inquiring look, and you give them a small nod, and actors appreciate that, the first human eye contact. It’s all about trust — they know you are looking out for them. That’s why you get thank-you notes afterwards.”

He adds that there are strong similarities between Mangold and Payne in how they handle actors. “On the morning of the shoot, we bring the actors in for blocking, and we don’t have too many preconceived ideas. When you have great actors, you want to see how they want to move — Harrison [Ford], Christian Bale … George Clooney — he is very aware. It is very important with great actors to have this blocking rehearsal. You don’t want to change it afterwards. I try to be very involved in the blocking. We don’t make shot lists beforehand; we watch actors use the space and then come up with a shot list — so the actors are not coming in saying, ‘I should be somewhere else.’ When I light it and set the first shot, they are comfortable with it.

Advising the Next Generation

Papamichael prefers to work with smaller crews, and says he found it very challenging to shoot films like Indiana Jones with a large team. “I do my small movies in Europe, like 27 Missing Kisses, Brighton 4th and Light Falls [the latter of which Papamichael directed] — it is very liberating. I tell young filmmakers who want to make big movies: ‘You have great freedom on small films. On Indy 5, I have 100 trucks parked here!”

He likes coaching younger cinematographers. He tells them to stay productive, not be too selective or highbrow at the beginning of their careers. “You will learn a lot from just being on set, and that’s how you find people. You want to find people whose approach or sensibilities are similar to yours — that’s how you are going to be successful, by forming these creative collaborations.”

Triple Play

In 2003 and ’04, Papamichael shot three films one after the other, each with a different director: Sideways (Payne), The Weather Man (Gore Verbinski) and Walk the Line (Mangold). There were just three weeks between each shoot. “That was when I really discovered what it is like to work with different directors!”

Sideways is about a trip two friends (played by Paul Giamatti and Thomas Haden Church) take to California wine country, and was “beautiful to do, very simple. Vilmos [Zsigmond, ASC, HSC] said, ‘This is perfectly shot.’”

Then he shifted to The Weather Man, which depicts the mid-life crisis of TV news meteorologist David Spritz (Nicolas Cage). “That was more Hitchcockian, pre-designed. It is not necessarily more difficult to shoot when everything is meticulously planned in advance, but I prefer to leave room to discover things as they unfold on set on the day of the shoot — like what the actors do in their performance, or getting the final impression from the set design or location, or the natural light at that moment.

“From the very rigid creative process of The Weather Man, I go to Walk the Line, and I am presented with Joaquin Phoenix. With him, I really don’t know what he is going to do! He keeps the entire crew on their toes — the same way Paul Giamatti and Thomas Haden Church always offered interesting interpretations of the Sideways screenplay.”

In one scene in Walk the Line, a frustrated Cash rips a sink out of the bathroom wall — action Phoenix improvised as the camera rolled. “That wasn’t planned! That sink was in the school since the 1930s! It became clear to me then, doing these three films back-to-back with very little prep, that I prefer the looser way of approaching the shoot. We don’t want to deprive ourselves of the improvisational and instinctive discoveries.”

“You want to find people whose approach or sensibilities are similar to yours — that’s how you are going to be successful, by forming these creative collaborations.”