DPs Who Direct

Three cinematographers’ unique paths into directing, and how years of work behind the camera continue to inform their creative choices.

One of 15 founding Society members, and a key organizer, Phil Rosen served as the ASC’s first president starting in 1919, but almost immediately shifted from the camera to the megaphone. Yes, cinematographers transitioning into directing is nothing new. In fact, it was more common back in the day, as studios valued the onset experience and technical know-how that cinematographers offered. And with the art form evolving so rapidly, production roles across the board were far more fluid than they are today.

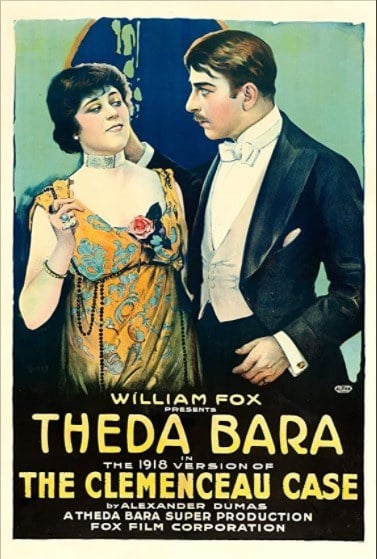

Born May 8, 1888, in Poland, and raised in Machias, Maine, Rosen worked as a projectionist and lab technician before becoming an $18-a-week cinematographer in 1912. He co-founded the Cinema Camera Club in New York City while working at the Thomas A. Edison Studio and later worked at Fox, where he shot several of Silent Era icon Theda Bara’s pictures, including The Clemenceau Case, The Two Orphans and Sin (all 1915).

Rosen came to California in 1918 to photograph writer-director George Loane Tucker’s The Miracle Man, starring Lon Chaney. The success of the film brought Rosen an offer from Universal to direct. Over the next 30 years, he helmed some 140 films, including the Rudolph Valentino feature The Young Rajah (1922) and The Dramatic Life of Abraham Lincoln (1924).

Rosen later became active in the formation of the Screen Directors Guild in 1936.

Today, the many active ASC cinematographers who have also directed include John Bailey, Bill Bennett, Uta Briesewitz, Joan Churchill, Curtis Clark, Dean Cundey, Jan De Bont, Caleb Deschanel, Ernest Dickerson, Eagle Egilsson, Anna Foerster, Michael Goi, Dana Gonzales, Kirsten Johnson, Ellen M. Kuras, Edward Lachman, Robert Legato, Chris Manley, Chris Menges, Reed Morano, Guillermo Navarro, Andrij Parekh, Wally Pfister, Alik Sakharov, Mikael Salomon, Lawrence Sher, Dennis Smith and Michael Watkins.

Recently, Parekh and Sakharov earned 2020 Emmy Award nominations for Outstanding Directing For A Drama Series, with Parekh taking home the gold for his work on for the Succession episode “Hunting.”

Below, three current ASC members describe their path to directing and how their experience as cinematographers have helped inform their creative process. — David E. Williams

By Michael Goi, ASC, ISC

I did not become a director because I was dissatisfied with being a cinematographer. I love the craft of cinematography. In fact, in episodic television I believe the cinematographer has the most influence to affect the aesthetic of a show from beginning to end. But I also realized early in my career that my cinematography only looked as good as the performances were excellent, so that balance of doing my lighting and making sure that the director and actors had the time to get the performance at its peak went hand-in-hand.

I remember first working with Evan Peters on the show Invasion when he was a teenager. By the time he was a regular in the American Horror Story ensemble, I had become familiar with his prep as an actor. He’d be off in the corner with his Walkman on, listening to music or whatever would psych him up for the moment. When he took the headphones off, I would immediately tell the crew to stop lighting. We were going to shoot. [To accommodate this kind of flexibility,] I would start lighting the set with only the key lights on the actors, so that if I pulled the plug on lighting the backgrounds because the actors were ready, at least I’d be able to see them. I suspect part of the dark style of the show that the fans loved so much was the result of my stopping the lighting process prematurely so that the director and actors could play.

It was an actor from “Coven” — the third season of American Horror Story — who kicked me into the director’s chair. I had only directed some shorts and a couple of small features previously. She came to me on set and said, “Michael, you direct, don’t you?” I told her yes, I did. She said, “I thought so,” and then simply walked away. What then transpired, I found out later, was that she went to the production and the network and asked why I wasn’t directing the show because — in her words — “Michael knows us better than anybody and he knows the show better than anybody.” Around that time, my agents had also been asking production about having me direct. Suddenly, I was told I would direct an episode in the next season, “Freak Show.” [Executive producer] Ryan Murphy had always given me a tremendous amount of creative freedom as a cinematographer, and he became my most enthusiastic supporter in pursuing a directing career, for which I am eternally grateful.

Between the two seasons, while I was shooting the show Salem in Shreveport, La., I was offered the chance to direct the pilot of a new horror show that was being produced by a good friend of mine. It was a smaller show, but it looked like it might be challenging and fun. When I discussed this with one of the writer/executive producers on Salem, he advised me not to take the job: “You’re going to start your directing career next season, doing one of the best shows on television — a job that everyone wants. That positions you immediately at the top. That’s what you want the perception of you as a director to be.” I took the advice.

Directing the episode “Magical Thinking” in American Horror Story’s “Freak Show” season went very smoothly. Because James Chressanthis, ASC, GSC — the additional cinematographer I’d brought on to help me get the episodes done that season — had to work with the next director, I had to both direct and do the cinematography on my episode (as I did on most of my subsequent episodes of the show). I was aided in this process by having my regular gaffer, John Magallon, constantly by my side. John and I had worked together so long, we could complete each other’s visual sentences. He knew that I never liked to go with my first idea for lighting a scene, and that I would sometimes completely change the lighting after a rehearsal with the actors because something they did inspired a different visual approach — and John is the person who enabled me to follow my flashes of accidental inspiration. As I’ve often said, I have created an entire career out of making enormous compromise look like an intentional style. John is an essential collaborator in that process.

My first episode was received very well, so I was offered additional episodes to direct in “Hotel” and “Roanoke” — the show’s fifth and sixth seasons. I had honed in on my directing methodology: When I first receive the script, I immediately start shot-listing. I mean, immediately. I do not scan the script first or give it the “once-over.” I read the first scene and I start writing down shots. It doesn’t matter that I haven’t seen the sets or locations, because the initial shot list is not about the physical reality of where things will be shot; it’s about remembering what’s important in the story. I read lots of scripts, and sometimes the words start blending together into a kind of incomprehensible stew, like the voice of the teacher in all those Charlie Brown animated TV specials. But by writing down the shots as I read, it forces me to understand what’s important in the story and what the character is going through.

For example, for an episode of Pretty Little Liars, I had a scene where Troian Bellisario’s character, Spencer, comes home to find that her boyfriend has moved out. The script references her feeling like the house was conspicuously empty, so I wrote in a wide shot with her small in the frame. It says she sees a postcard on the bed, looks at it and lies down feeling lost and alone, so I wrote in a close-up of the postcard, a close-up of her, and a very high wide shot as she collapses on the bed. Those shots come from my cinematographic knowledge of how certain kinds of shots tell the story more effectively than other shots. And it speaks to my knowledge of exactly what type of lens or camera mount I may need to get the shot I want.

The critical thing to understand here is that this is the beginning of finding your “style” as a director. It comes from inside you, and what kind of shots you think will convey how the character feels in that moment. I learned that from watching The Graduate when I was 8 years old; the camera composition and the lighting were always showing me how Dustin Hoffman’s character, Ben Braddock, felt. The cinematography by Robert Surtees, ASC wasn’t interested in giving us a pretty picture — it wanted to make the audience feel like they were the character. So my initial shot list reflects that point of view, and that becomes the style of the show. It’s like giving a piece of classical sheet music to five different conductors; you’re going to get five different interpretations. As prep continues and more logistical specifics become evident, the shot list is revised and I add little drawings that are incomprehensible to anyone but me. But the shot list has served its purpose; the assistant director has an idea of how many setups you think a scene will have, the cinematographer can determine if special equipment is needed, the art director can assess if walls need to be able to be movable, etc.

Once I am on set actually directing, I never look at my shot list. By that time, I have drilled the story into my head and I know the types of shots I need to get to tell the story, but I don’t need to get into specifics until after I work with the actors on blocking. When the actors leave to get makeup touch-ups, I gather the entire on-set crew (who have just watched the blocking rehearsal) and I walk through every setup so that everyone knows in which direction I plan to shoot, and the sizes and types of shots. Then the cinematographer, camera operators and I talk, and they make suggestions (“If we lay 10 feet of dolly track, we can combine these two setups”). This helps eliminate so many questions and makes filming go quickly.

Years ago when I was a cinematographer on a feature film, I had an intern who noticed that everyone asked me questions all day long, so the next day she showed up with a hand counter. Every time someone asked me a question, she would click it. At the end of a 12-hour day it was 3,753 questions. And there are no unimportant questions during a production. (“Can I park the trucks here? How many times will you shoot the glass breaking? Will you see this jacket from behind?”).

One of the smartest things I did, when it became evident that directing more often was a real possibility, was to apply to a studio directing program — the Warner Bros. Television Directors’ Workshop. When they interviewed me they asked why I was applying, because I had shot so many shows for the studio as a cinematographer and they could just add me to their list of potential directors. I didn’t want that. I wanted to get into their established pipeline for training directors for their shows, because it indicated to everyone at the studio who knew me as a cinematographer that I was serious about becoming a director. So they accepted me into the program, and while I went through the course, they started checking my availability to direct shows, and they booked me on my first three episodes away from American Horror Story.

Another thing that I carried over from cinematography to directing was being on set when the camera rolled on the actors. I like to stand right behind the A-camera operator and watch the actor live from 6 feet away. It always used to drive me crazy when directors would sit in a chair with a cappuccino and headphones and watch the shot on a monitor, then scream adjustments to the actor from another room. So many actors have told me that it heightens the stakes in their performance when I’m on set, because even if they can’t see me, they know that I’m actually there in the room watching them.

I’ve heard every excuse in the book from directors about why they need to be at video village, like, “I need to watch the focus.” Frankly, that’s the 1st AC’s job. Or, “How will I know the operator got the shot?” It’s simple. Trust your crew. We rehearse with the stand-ins while the actors are getting made up, and I look at the monitors and give instructions to tighten up a shot here or start the dolly sooner there. When the actors come onto the set, it’s all about getting the performance for me, because the technical side of what we need to do has been worked out.

When I get a performance I love from an actor, upon calling “cut” I immediately ask the crew if everyone is good. That is their time to give me the thumbs up, or say they need another take. If anyone says they need another take, I don’t ask them why. It doesn’t matter why — the shot didn’t work. All I need to hear is that we need to do another take, and I say, “Let’s shoot it right away.” If you stand there and start asking, “Why do you need another one? What part of the shot didn’t work?” — what happens is that you humiliate the crew and you shatter the actors’ confidence in them.

I also like to cut the camera between performances. It was always like that when shooting film, but digital video production has led to a culture of “let the camera roll” while crew goes in and adjusts wardrobe, makeup is touched up, grips adjust flags, etc. This works against the director in post-production, because instead of putting together a really good editor’s cut, the editors are now spending a lot of their time searching through 40-minute takes for the 20 seconds that are good. “Cut” is a wonderful word. It signals the end of the performance, it signals the time that the crew can move in and tweak things, and it is the start of the anticipatory couple minutes before “roll camera” is heard, and the magic starts again.

My experience as a cinematographer informed and enhanced my abilities as a director. It made me understand the value of getting the workday done in a reasonable amount of time so that safety would not be compromised because of crew exhaustion. It enabled me to communicate my ideas clearly and concisely because I spoke the same language as my camera, grip and electric teams. And it enhanced my never-ending quest to be a visual storyteller.

For more on Goi and his time on American Horror Story, check out this interview from the show's second season, “Asylum.”

By Ernest R. Dickerson, ASC

Cinematography was my first love; it is what drew me to filmmaking in the first place. I minored in color photographic illustration in undergrad and majored in cinematography in graduate film school, so photography has long been a part of my life. But, I must admit, there were certain directors whose work always fascinated me, and they were all strong visualists — directors like Orson Welles, Akira Kurosawa, Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick, Nicolas Roeg and David Lean, among others. All directors who were strong users of photography to tell their stories. Their works started me thinking about the possibility of directing. But cinematography came first.

A couple of years after graduating from NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts, I shot my first professional film. In the meantime, I shot the occasional music video, but I also co-wrote the screenplay for what would eventually be my first film as a director. But that was nine years away. My first professional cinematography job, The Brother From Another Planet, was unusual in that the director, John Sayles, also acted in the film. Usually when that happens — as it did in this case — it puts the cinematographer in a co-director position when the director is in front of the camera. That happened again two years later, when I shot She’s Gotta Have It for director Spike Lee. An actor fell out at the last minute and Spike had no choice but to play that role himself. So again, I acted as director whenever he was in front of the camera. This situation lasted for the next four films we did together — until, while in pre-production for Jungle Fever, a young Englishman named David Heyman, looking to produce his first film, told me he wanted to finance the production of the script I’d co-written nine years before. That script became the movie Juice.

Juice was conceived as a film noir. So everything I learned from studying the films of Orson Welles, and of Alfred Hitchcock in his collaborations with Robert Burks, ASC, I put into the look of my first film. I believe that 85 percent of directing is casting, but after that, the camera became my primary weapon. On my set, the camera only goes where I put it. My past experience has allowed me to build very intense collaborations with my cinematographers. John Huston, one of my heroes, said that every film should have its own look, its own color palette. I believe that. For me, pre-production is the most important part of putting a film together. Working out the look and the palette with my cinematographer is a part of the process I love a lot. It is the two of us inventing the paintbrush that will paint the picture of our movie. I will never give up the photography.

Casting, to me, is the most nerve-wracking part of putting a film together. The reason I feel it is 85 percent of directing is because with the help of the casting director, you find that actor who can become the character you need them to be, and they will become that character without your help. I discovered this on Juice, where my casting director was Jaki Brown-Karman. It was painful searching for the right actors to play my four main characters, but in that search we discovered Tupac Shakur! It’s about pushing the casting process and never settling. Never giving up until you find that one right person will reap rewards that will ultimately give you that character you dreamed about. Once you have that, you can sit back and become the first audience for the film. Adjustments may need to be made here and there, but hopefully they will be minor. Then you can enjoy what you created before anybody else.

After I directed Juice, I went back to Spike Lee’s company to photograph Malcolm X. It was a purely emotional decision, based on my admiration of Malcolm and my love of his autobiography. At that early point in my career, I hoped to be able to bounce between directing and cinematography on those projects that affected me accordingly. Some scripts I wanted to direct. Others I wanted to shoot. But in this business, you get known for doing one thing only. Some folks wouldn’t hire me as a cinematographer because I had directed. Other folks couldn’t figure out if I was a director or a cinematographer. It was a mystery to me, but I had to make a choice, and I chose directing.

So now I am a director who, at heart, is still a cinematographer. I love working out how I will use the camera to tell the story. I always break down the script with my cinematographer and do a scene-by-scene analysis to discuss looks, lighting, moods and visual textures. Then, on the set, I always step back to let the cinematographer do their thing.

But I am a dictator on camera placement and movement and what we will see. I explore still photographs, paintings and other movies to share with my cinematographer and production designer to lock down the look. It all becomes more concrete on the location/set scout, when I decide exactly what part of the set or location I will use to block and choreograph the actors and the camera. I have been drawing since I was a youngster, so I often draw my own storyboards, creating a visual script on the blank opposite page of my script.

My life mantra is, “Creation is a patient search.” Planning a film or television episode is always going to be a search for the solutions to the myriad problems that are going to come your way. I always tell young filmmakers that the crew will bombard you with questions at the start of pre-production. Don’t be afraid to say, “I don’t know right now, give me some time.” But when your patient search finally yields results, it’s the best feeling in the world!

Learn much more about Dickerson's creative process behind the camera in this AC article about the making of the Spike Lee drama School Daze (1988).

By Dana Gonzales, ASC

The on-set experience an established cinematographer brings to their first directing assignment can’t be underestimated — that understanding of how a crew functions and how to avoid the pitfalls of production. But that’s just part of the equation.

My first opportunity to direct came on the series Pretty Little Liars. I shot the pilot, and after it got picked up, my collaborators on the show supported me and I was later offered the chance to direct. I learned that, as a cinematographer, certain things just come together, but as a director you’re responsible for all the decisions that guide that process, even while they are progressing based on decisions from your department heads. And you have to trust that process and understand how they are trying to support the vision you’ve communicated to them.

Collectively, an established TV show can run itself without a director. But what will make an episode stand out is a point of view that brings together the cast and crew’s contributions in a unified way.

A seasoned cinematographer who is only focused on the camera and lighting can always deliver “coverage,” and you can make a show out of that. But the showrunner/ writer’s perspective — and even in editorial — will be that there’s no point of view driving those choices with the hope of elevating the episode. That said, in a police procedural or courtroom drama, you have to get the coverage and the point of view will be built in editorial, while a show like Mindhunter or Ozark will want a distinct directorial point of view.

Directing is a bigger commitment than people think, but the offer to direct in television — especially for someone already known to the production as a cinematographer — is usually the result of people liking what you’re already bringing to the show. Television is a medium where the producers see somebody’s dedication and skills and put them to best use. That said, I don’t think every DP wants to direct.

Pretty Little Liars, 2.18 - "The First Secret" Directed by Dana Gonzales

A major advantage for cinematographers directing [on a series they have also shot] is that the actors will — hopefully — like and trust you. They have seen how you’ve cared for their image and helped support their performance. If you’ve established trust, they will try new things if you need them to for dramatic reasons — otherwise, they can become very protective. They have been creating and inhabiting a role maybe for years, so that trust has to be there. Your shorthand with the crew will also help. That said, some actors will see you as “just the DP.” They know and may like you, but… And you have to overcome that and prove yourself. But that’s part of the job.

I just finished shooting three and directing four episodes of the current season of Fargo, ending with directing the series finale, as we’d returned to complete our work after the Covid shutdown. We were concerned about our safety protocols at first, but after the first day we realized it was possible, and then the following days became easier, and we finished with no issues. Also, a factor was that I’ve been involved with the show since the first season, so I know what point of view I’m bringing to the story — which is one of the most important things about directing: offering an interesting perspective that makes the most of the story, characters and tone. Being so familiar with Fargo helped us focus more on our procedures to remain safe.

I had two cinematographers shooting my episodes of Fargo this year — Erik Messerschmidt, ASC and Pete Konczal. Erik has shot for me on the show Legion, and both are very accomplished. I hired them because I like their work, not because I want to micromanage them.