Django Unchained: Once Upon a Time in the South

Robert Richardson, ASC re-teams with Quentin Tarantino on the story of a former slave seeking revenge.

Photos by Andrew Cooper, SMPSP

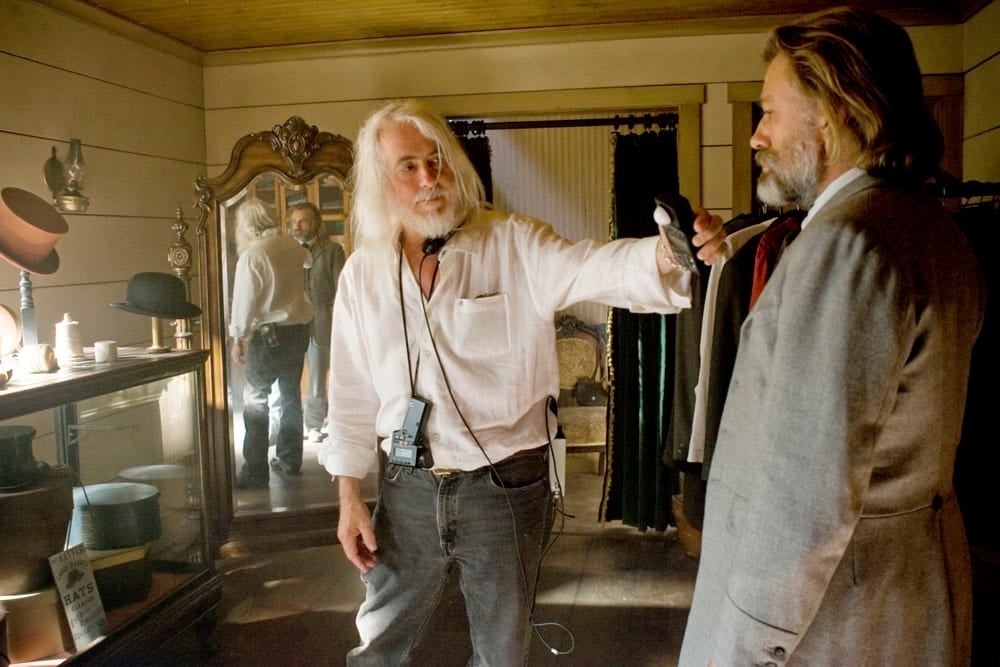

Quentin Tarantino’s previous collaborations with Robert Richardson, ASC — Kill Bill (AC Oct. ’03) and Inglourious Basterds (AC Sept. ’09) — quoted liberally from the visual vocabularies of Italian Spaghetti Westerns, but with Django Unchained, the writer-director blazes his own trail. “This time,” says Tarantino, “I’m doing a ‘Spaghetti Southern.’”

He goes on to explain that the bleak, pitiless universe of Spaghetti Westerns seemed like the ideal setting for the story of a freed slave in the antebellum South. The former slave, Django (Jamie Foxx), is trained in gunslinging by a charismatic bounty hunter, Dr. King Schultz (Cristoph Waltz), who then hires him to help him track a posse of bandits called the Brittle Brothers. In return, Schultz agrees to help free Django’s wife, Broomhilda (Kerry Washington), from the clutches of wealthy plantation owner Calvin Candie (Leonardo DiCaprio).

“Quentin still knew exactly what he wanted to shoot, but this time, he was willing to come in and develop a scene based on the moment, which was a little unusual in my experience with him.”

It has long been Tarantino’s custom to screen dozens of movies for his key creatives early in prep to help establish the language of the universe they will create. For Django Unchained, Richardson recalls, these screenings included Sergio Corbucci’s The Great Silence, Dario Argento’s Suspiria, Lucio Fulci’s Don’t Torture a Duckling, Mario Bava’s Black Sunday, Max Ophüls’ The Earrings of Madame de …, Brian De Palma’s Carrie, Sergio Leone’s For a Few Dollars More and Howard Hawks’ Rio Bravo. “That’s by no means a complete list,” adds Richardson.

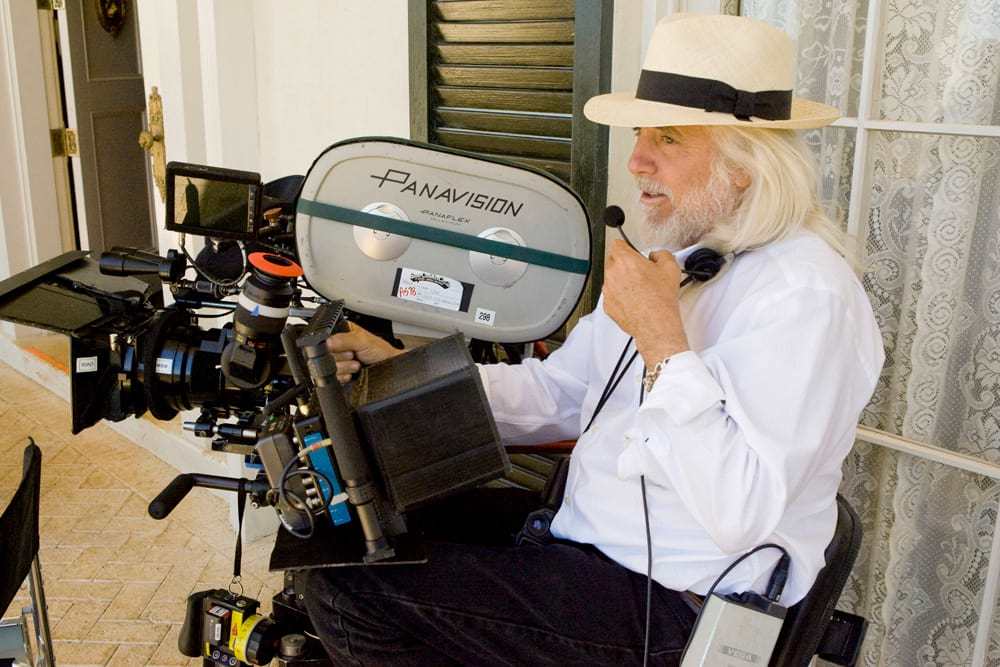

The cinematographer and his core crew — gaffer Ian Kincaid, 1st AC Gregor Tavenner and key grip Chris Centrella — have worked together for so long that the cinematographer can issue any number of specific commands with the mere wave of a hand. Richardson also wears a headset that enables him to communicate with them, and occasionally other crewmembers, from his perch behind the camera.

“Bob has trained all of us to be sensitive to the way a scene progresses,” says Tavenner. “Even a single close-up can contain a lot of information, so you have to be able to feel what that moment is really about.”

“Bob always lines it up the way I ask, and then I look through the viewfinder and it sucks — it’s not magical,” the director concedes, chuckling. “Bob has very strong opinions, but he doesn’t editorialize. He just wants to know what’s in my head. That’s a crazy amount of trust.”

The filmmakers decided to shoot anamorphic 2.40:1 and use the same Panavision Primo lenses they had chosen for Inglourious Basterds. Tarantino’s affection for wider focal lengths meant the 40mm or 50mm was often on the camera. “Quentin doesn’t like the foreground-background separation that a long lens creates,” notes Richardson. When a lighter camera configuration or a focal length not covered by the Primos was needed, the cinematographer used Panavision E-Series primes. “The eight E-Series lenses, which range from 28mm to 180mm, are completely compatible with the Primos,” says Tavenner, “and they’re not only beautiful, they’re also beautiful wide open. Bob has a tendency to light to a T3.2.” (The lens package also included Primo 48-550mm ALZ11, 40-80mm AWZ2 and 70-200mm ATZ zoom lenses.)

After principal photography commenced, Tarantino continued to revise the script based on his work with the actors, or to reflect casting changes. Because of this, tests involving new sets and costumes were shot whenever Tarantino, Richardson, Kincaid, costume designer Sharen Davis and production designer J. Michael Riva could find a free moment on set. Kincaid recalls, “We’d sometimes have our riggers set up panels of different colors and textures of paint in an environment that we’d lit in the style we intended to use in those particular locations, and then send a B camera over to roll some footage. That way, Michael and Sharen could adjust their colors to our lighting.” (When Riva died suddenly mid-shoot, art director David Klassen assumed the production designer’s responsibilities in addition to his own.)

A historic plantation in Wallace, La., called Evergreen served as Candie’s plantation, Candieland. The production used Evergreen’s mansion and slave quarters for some interiors and exteriors, as well as its oak-tree alleys and sugarcane fields. The art department spent five months constructing a 90'-wide-by-45'-high façade for the mansion exterior, which featured six Greek Revival-style columns that were 30' high. The first and second floors were art-directed approximately 20' into the façade to match the two-story interior set built at Second Line Studios in New Orleans.

Tarantino describes two different approaches to camera moves in Django Unchained in terms of other filmmakers: “When we’re outside, it’s Sergio Leone and Sergio Corbucci. Inside, especially in Candie’s mansion, it’s Max Ophüls.” Richardson elaborates, “One of the things Quentin brought up almost immediately [in prep] was how Fulci and Corbucci use the zoom. Often their work utilized zoom actions that mimic a dolly but have a vastly different sensibility. Whether the choice was budgetary or aesthetic is open to argument, but we embraced it as an aesthetic. We screened Ophüls’ films for the long, fluid camera moves. Django became a combination of these two styles; we were often doing crane moves or dollies in conjunction with a zoom.” When Tarantino requested it, Richardson would punctuate the drama with snap zooms, which he pulled by hand.

The Candieland mansion interiors exhibit “a really elegant, 1940s-studio-film look, with big, sweeping crane shots,” says Tarantino. “Bob and Michael Riva and I screened 35mm prints of films like The Exile and Letter from an Unknown Woman for those scenes.”

In one such shot, the camera tracks Candie’s right-hand man, Stephen (Samuel L. Jackson), as he walks through the kitchen and then moves through a swinging door into the dining room, where Candie, Shultz and Django are dining with Candie’s sister, Lara Lee (Laura Cayouette), and his lawyer, Leo Moguy (Dennis Christopher). Richardson is riding a GF-8 crane with the Primo AWZ2 set at 80mm. He zooms back with Jackson, and the crane tracks with Jackson as he moves from one room to the other until the camera passes through a wall to frame the dinner table in a wide shot. The crane tracks past Jackson as he stops at the head of the table, and continues tracking down the length of the room. Slowly, the arm of the crane swings around the far end of the table while zooming into a medium close-up of Foxx in profile. Meanwhile, Centrella and his crew fly in the outside wall to provide Richardson with a wider frame. “As the camera came around to the profile shot of Jamie, we dimmed down Samuel’s backlight and brought up Jamie’s backlight,” notes Kincaid.

When a crane shot is required, Richardson prefers to ride with the camera instead of operating remotely from the ground. Typically, Tarantino will ride the crane first to show Richardson what he has in mind, and then, after a couple of rehearsals, Richardson will take the reins. Usually, Centrella and crane tech Mike Duarte operate the chassis, and dolly grip Dan Pershing handles the arm. Richardson favors OConnor’s 120 EX fluid head over gears.

For another shot in the mansion, the camera was on a 45' GF-16, shooting through the banister of the main staircase. The focus starts on the hem of Lara Lee’s dress as she escorts Broomhilda upstairs to Schultz’s room. The camera booms up the stairs, tilts to reveal the women, and follows them at eye level around the second-floor balcony. “We were on 50 or 60 feet of track starting at the door,” recalls Centrella. “We tracked with the bottom of the dresses and boomed up to the top of the steps, and then we swung around and tracked backwards towards Schultz’s room.”

For the close-up, a set of oversized steps was built on the mansion-interior set at Second Line. The banister was removed from the camera side, and the grips rigged 32' of track parallel to the angle of the staircase and used a wire rig to motivate the camera. Because the sequence involved interior and exterior spaces, the master had to be staged on location at Evergreen. Though Riva had designed the entryway of the façade to match the full-sized set at Second Line, it was never intended to accommodate interiors, so doorways and ceilings were missing and the main staircase was foreshortened.

“There wasn’t much traction on those stairs [at Evergreen],” McConkey recalls, “and Walt was wearing spurs that made his feet several inches longer, so he couldn’t get the balls of his feet all the way on the step. He had to balance himself like a dancer, with his hands in the air, as he came down. That image was so incongruous with Crash’s evil nature it was pretty funny.”

As Goggins descended the stairs, McConkey rode a modified GF-16 crane parallel with the actor, framing him in a medium profile at the same profile angle as the close-up, and then stepped off the crane at the bottom of the stairs to follow him onto the veranda. The shot ends on the lawn, with Crash sizing up one of the more physically intimidating potential fighters. “With a shot like that,” notes McConkey, “you’re not just following an actor. You have to be aware of the subtleties of each moment, and every move has to be just right. We finally found [what we wanted] at the end of one of the takes. I was framed on Walton, and then I tilted up slowly when he looked into the man’s face, and then tilted back down with him. A second later, he shoots the man in the chest. It’s comedy and brutality in one take.”

Richardson recalls that Tarantino was more improvisational in devising shots on Django than he was on their previous collaborations, which involved handwritten shot lists provided each morning. “Quentin still knew exactly what he wanted to shoot, but this time, he was willing to come in and develop a scene based on the moment, which was a little unusual in my experience with him,” he says.

In terms of lighting, says the director, “my input is so minuscule that it really doesn’t exist. I love Bob’s look. I love his atmosphere. I love his hot pools of light. I love all that shit. It’s taken my work to a different level.”

On day exteriors, “there wasn’t a lot we could do for the wide shots, of course, but we’d often try to situate the sun behind the actors when they were out in the open,” says Kincaid. “Otherwise, we’d try to stage day exteriors in forested areas. In both cases, the grips rigged 30-by-40-foot vintage charcoals overhead that shaded everything, but still allowed nice soft light through. When we got into close-ups, we’d bring in some negative fill and passive fill — big muslin bounces to add light and big solids to take it away.”

The film’s numerous wide night exteriors, many of which were shot at Big Sky Ranch, were a larger concern for Richardson, particularly when a zoom lens was involved. “How do you light a vast Western landscape for a T4.5 or T5.6?” he muses. He often pushed Kodak Vision3 500T 5219 to ISO 1,000. “I’m sure we were seeing up to a mile of background in every direction,” says Kincaid. “There was no light out there, and there wasn’t supposed to be any. The only motivation was moonlight ambience.”

In one scene, the Brittle Brothers and a posse of torch-wielding bandits ride across the countryside in pursuit of Django and Schultz. Richardson’s crew used four 15-light Bebee Night Lights and three 40'x40' truss frames with 24 DMX-controlled open-bottom space lights each to light the action. Gelfab Full Blue Silent Grid Cloth was hung beneath the trusses to cool the toplight. “Most of the time, we were told in advance if the shot would involve the Primo zoom,” Kincaid recalls. “Sometimes we’d start with doubles in all the lights or three globes in each of the space lights, and when the zoom came, we’d snap on all six globes in each of the 24 space lights, pull the doubles out, and Bob would push the film.”

“Quentin prefers to start at the beginning of a scene and work his way through it, even if one angle might be repeated at the end of the scene.”

Night interiors were keyed with a mix of flame sources. “Back then, practicals were candles, kerosene lamps and whale-oil lamps,” says Klassen. The filmmakers used candles and period-correct fixtures that ran on propane. “We drafted the special-effects department to help us,” says Kincaid. “They had propane running into 3-foot and 4-foot flame bars. In a small room, we’d use three 4-foot bars in front of big muslin bounces and just let the flames do the flickering.”

Gas fixtures feature more prominently in the Candieland mansion and the exclusive Cleopatra Club, where the practicals were augmented with dimmable 650-watt peanut bulbs. “There’s a subtle difference between the feel of gas lamps and electrical ones, but we never used [our lights] to key the scene,” says Kincaid.

Paper lanterns holding 300-watt household bulbs dimmed 33-66 percent were also used for augmentation. For large night interiors, Kincaid’s crew built walls of these household bulbs, using as many as 200, behind frames of bleached muslin. “We like a dimmed-down, crushed bulb that emits a really gentle light, so rather than use something like a Photoflood, we’ll use large panels of household bulbs and crank them way down on the dimmer to create a big, soft glow,” notes the gaffer.

Richardson also tapped a soft book light, a 12-light Maxi-Brute or Nine-light Mini bounced off unbleached muslin and back through bleached muslin, using 8'x12' or 12'x20' frames, depending on the size of the room. “We usually had the lights backed off far enough that they were easy to control, but we weren’t afraid to put the grips to work!” says Kincaid. “They put up lots of solid floppies and 20-by-4-foot bottomers and toppers.”

When working with softer light, Richardson favored the Primo primes over the E-Series anamorphics. “A Primo is so truthful in its translation of what’s in front of it,” says Tavenner. “With the older anamorphic lenses, you can throw all that light at a scene and they will soften it. Bob’s lighting is so soft that he benefits from the Primos’ ability to capture all that resolution and detail.”

When Richardson wanted to soften a shot, he’d ask Tavenner to glue a stocking across the rear element of the lens. This was done mostly for scenes set in the South to reduce overall contrast and add a slight bloom to the highlights. “That reflects the nature of the light down south, which is kind of humid, a little glowing,” Tavenner notes. The stockings varied in their styles and patterns, “but [the effect] mostly depended on how it was stretched and matched to the different focal lengths,” says Tavenner. “Over the years, all these nets have gotten mixed up in my kit, so I just grab a stocking and judge the quality by eye.”

Deluxe Laboratories and its subsidiary EFilm in Hollywood handled the production’s post workflow, processing the negative, creating film and digital dailies, and facilitating the DI. Colorist Yvan Lucas supervised all of the timing; ASC associate member Adam Clark timed the film dailies, which were viewed by Tarantino, cast and crew; and Benny Estrada timed the digital dailies, which were generated from 2K scans of the negative and screened by Richardson and editorial using eVue, part of EFilm’s CinemaScan system.

Richardson notes that Tarantino initially wanted to try a photochemical finish, but ultimately conceded to the realities of digital distribution. “He wants to get this film in as many theaters as possible,” Richardson comments. Even so, he continues, “my work with Yvan essentially duplicated what we would have done in the lab. We worked in points. Of course, there are more variables in the digital space, so we can work with quarter points, but the concept remains the same.”

Deluxe’s proprietary Adjustable Contrast Enhancement silver-retention process was applied to the Western portion of the story in the print dailies, and the team applied a digital approximation of that look to the CinemaScan dailies and to the final grade. “Through testing, we ended up at a near 50-percent application of ACE, which Deluxe numbered 152,” says Richardson. “The creative intention was to create a desaturated look with deeper blacks. When Django and Shultz travel to the South, ACE was dropped, and the result was an apparent increase in chroma. In the digital realm, Yvan added 15-percent desaturation and an increase in contrast to mimic the look of ACE, but there is no way to fully replicate the chemical properties of the process digitally.

“The film was vastly more beautiful, in my opinion,” adds Richardson. “Soon, unfortunately, this process will be more and more difficult to see due to the rise of digital cinema and the slow burnout of the companies that produce film stock.”

Most of the work in the final grade involved evening out the densities between shots, however. Richardson explains, “Quentin prefers to start at the beginning of a scene and work his way through it, even if one angle might be repeated at the end of the scene. So, let’s say you have a 15-page scene to be filmed over a number of days. The weather is never going to be consistent, so there will be mismatches. I tend to want to shoot the actors backlit, knowing that if it gets overcast, backlight looks more like overcast weather than frontal light. But sometimes it didn’t serve Quentin best to shoot that way. But that’s okay. He’s not there to make a beautiful-looking picture; he’s there to make a great movie, and that’s what I signed on for. Always have, always will.”

You'll find AC’s coverage on Richardson and Tarantino’s follow-up feature, Once Upon A Time... in Hollywood, here.