Don Burgess, ASC: Making Each Shot Work

The cinematographer reflects on his storied career, and the personal and professional support system that helped him navigate it.

There’s a powerful stormy sea off the coast of Fiji, and Chuck Noland (Tom Hanks) is about to board a makeshift raft amid the raging whitecaps. “This is the moment showing Chuck has decided he doesn’t want to live any longer, a moment of imminent failure,” recalls Cast Away cinematographer Don Burgess, ASC.

“[Director] Bob [Zemeckis] wants a dolly shot circling around Tom, and he says, ‘How are we going to shoot this?’” Burgess continues. “I said, ‘We got this — it’ll work,’ and the look on Bob’s face was just disbelief. We hooked a Libra Head onto the front of this Avon rubber roundabout craft, and Bob said, ‘This will never work!’ as he’s watching this little raft just get bounced and thrown about by the seas. I said, ‘Look at the monitor!’ The shot was beautiful and totally steady on Tom. Bob just said, ‘Great, let’s go!’ That’s how we work together.”

This kind of quick thinking — shaped by years in sports and being behind the camera on documentaries and 2nd-unit action filming — is just one strong suit that sets Burgess apart. Recognizing his many other attributes as well, the ASC is honoring him with its Lifetime Achievement Award this year.

California Roots

Burgess was born in the same Santa Monica hospital where his father was, and raised with three siblings (two sisters, Romney and Chris, and a brother, Rick) in the Pacific Palisades. His father designed and built swimming pools for the rich and famous — and Burgess, who spent summers working on those construction crews, was expected to take over the business one day.

“Sometimes I think I might have been better off if I had,” Burgess says with a laugh. “Dad made a very good living, but my passion became shooting, and my parents supported me in that passion.”

Burgess’ interests included skateboarding and football; he was the quarterback on his high-school team. “When I was 10, I was on a skateboard team in the Palisades, and we got hired to be in a TV commercial, eating Hormel hot dogs and skateboarding around Descanso Gardens. Mike Murphy was the cinematographer on that, and he was using all kinds of great camera rigs and getting all these cool angles. I thought, ‘What a cool job!’”

Burgess’ sister Chris took a photography class in high school and “came home excited about photography,” he recalls. “Dad took a room and turned it into a darkroom for her, and that’s where I got hooked. I saw my sister develop her first print, and I jumped in and learned about it. Photography just grabbed hold of me, and when I figured out that I could make a living along those lines, I headed in that direction.”

“Ultimately, the cinematographer is the one who has to make the shot work. We have to love what we do and be able to say, for better or worse, ‘That’s it, that’s the shot.’”

An Eye for Action

Burgess enrolled in the photography class and soon sparked to the possibility of motion pictures. “I ended up making my first Super 8 movie in high school, and, of course, it was a ‘Warren Miller’ kind of movie with my buddies. I showed that at school.”

With a laugh, he notes, “Once you get your first round of applause, you’re hooked. Between the photography and filmmaking, I began to develop an understanding that I could travel the world and shoot things that I found interesting, which at the time was mostly sports.

After graduating, he was hired to shoot games for the football team. “I got to shoot in black-and-white, run the film into Hollywood, and then bring it to the coach. I was paid $100 a game, and I thought I had died and gone to heaven!”

Burgess’ passion for photography led him to apply to the ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena. His classmates included future ASC member (and current president) Shelly Johnson.

Recalls Burgess, “While I was at ArtCenter, an adventure filmmaker named Mike Hoover came in and gave a guest lecture.” Hoover had been nominated for the Academy Award for Documentary Short Subject for the 1972 climbing film Solo. “He also shot the bicentennial climb up Everest, and I thought that was amazing. He showed us 2nd-unit footage he’d shot for The Eiger Sanction [AC, Aug. ’75]. After the lecture, I went up and introduced myself and said I’d love to do what he did, and he said, ‘Have you shot anything?’ I said, ‘Yes,’ and he said, ‘I’ll come back on Tuesday and you can show me.’

“He came back, and I showed him a 15-minute political documentary I’d made about a local police officer who transferred out of the area, as well as a ski movie I made with my lifelong friend Chris Woods, set to the Boston song ‘More than a Feeling.’ He liked my films and ended up hiring me for his next climbing documentary, The Eye of the Gods, which was about four climbers who made a first ascent up the 2,000-foot mountain of solid rock, Autana, in the jungles of Venezuela. I worked for Hoover on many adventure documentaries and learned how to make films with a three-person crew in extreme conditions. He was a wonderful mentor and is still a good friend today.”

Another influence was ArtCenter instructor and commercials director Mike Ahnemann. “He would get the students involved to go out on real sets,” Burgess recalls. “He connected with the kids, and he was a confidence-building teacher — one that gave you the feeling you could actually pursue this as a career.

A Burgess family friend was cinematographer John M. Stephens. “I kind of watched Johnny from afar,” Burgess says. “He was primarily an action guy and a very successful director of commercials as well — Porsche spots. And I just kind of thought, ‘How do you do that?’”

Earlier Development

In the spring of 1976, during Burgess’ junior year at ArtCenter, Stephens was hired to direct and shoot 2nd-unit footage on a feature filming in the Dominican Republic, and he invited Burgess to assist on the project. It would mean missing out on the end of the academic year. Stephens took his 1st camera assistant, future ASC member Steven Shaw, to see ArtCenter dean Jim Jordan and try to convince him this would be an amazing opportunity for Burgess. Jordan agreed.

During production in the Dominican Republic, director of photography Dick Bush, BSC had to leave the show, and Stephens took over the main unit. Burgess spent the next three months working as a loader on what would become William Friedkin’s Sorcerer.

Upon returning home, Burgess applied to the camera guild but was turned down. He returned to ArtCenter to finish his degree. “It kind of worked out for me that I didn’t get into the union at that point,” he says. “The union made the mistake of letting all this non-union work happen in L.A. because they were a closed shop, and due to that, I was able to develop as a DP at a much younger age than if I had entered as a loader and come up that way. I became a better cameraman at a younger age.”

Disney’s Boat

In the late ’70s, Burgess joined cinematographer and future ASC member Bob Steadman to work for supervising cinematographer Stephen H. Burum, ASC on a sailing documentary directed by Ahnemann. “Bob Steadman, one of the creators of the Weaver Steadman head, was a DP and operator and a sailor,” Burgess says. “I ended up on Roy Disney’s boat, Shamrock, with an Arriflex 16SR and just three magazines of film. There were a number of other cinematographers on the film, including [future ASC member] Joan Churchill, and Burum looked at me and said, ‘Well, Don, you’re the wild card here. You’ve got a chance to show people what you can do. I expect a lot out of you!’ Well, that was no pressure!

“On the morning of the race, I woke up sick as a dog and thought, ‘I’m not gonna miss this opportunity.’ I dragged myself out of bed and to the boat. I’d shoot and then would have to go below and reload the magazines. I was sweating like crazy and trying not to lose it down below. The last thing I wanted was Roy thinking, ‘Oh, great, the young documentary cinematographer is sick! Perfect.’ But I made it through without losing it and then collapsed at the end of it. It was a great experience, and the hook was really set in me for cinematography.

“Bob also turned out to be a good friend,” he adds. “As an experienced cameraman, he was always there to answer any questions for me and support me along the way.

“I didn’t learn how to make movies on a level ground — I made them out in the world with great adventure filmmakers. I’d be in Venezuela hanging off a cliff in the rain — in situations where if we didn’t shoot, it never happened. I was doing all these crazy things to get the shot. You have to think on your feet and get the pieces so that when you get to editing, you can make the scene. I inherited a lot of that kind of thinking from Mom and Dad. He could fix anything; he would solve problems, and I picked up on that kind of logical thinking.”

Scaling Up

Burgess’ career took another turn when he connected with stunt coordinator/2nd-unit director Max Kleven. Kleven hired him to shoot 2nd unit on Runaway Train. “It was in the 2nd units that I ended up having to manage big crews and big night exteriors and big sets. I worked with Musco lights and many cameras and had to figure out how to pull off all kinds of tricks and stunts. I got amazing experience strapped to the skids of helicopters, jumping train cars. My athletic ability came into play as a DP and operator; I could accomplish shots the other guys couldn’t, like skiing backwards or rappelling off mountains.”

When Kleven put together his own independent action film, Ruckus, he invited Burgess to photograph it. “That was my first feature — a 30- day, 30-setup-a-day movie, all action. Max was a guy who didn’t really play by the rules. He said, ‘Don is my cameraman and that’s that.’ It was an opportunity to shoot a feature-length movie at 23 or 24 years old.”

He continued to shoot main unit on independent films, including his ASC-nominated feature The Court-Martial of Jackie Robinson, while shooting 2nd unit and documentaries.

Burgess reflected on this period when he spoke to AC about Cast Away (AC Jan. ’01): “Once you establish yourself in a certain area, people begin to think of you in that one way, and it’s very difficult to break out of the mold. I walked away from 2nd-unit work for a while and tried to break into the A-unit realm as a lighting cameraman, but it just wasn’t working. I got stuck back in low-budget films and cable movies and couldn’t break out, so I finally went back to 2nd unit for a while.”

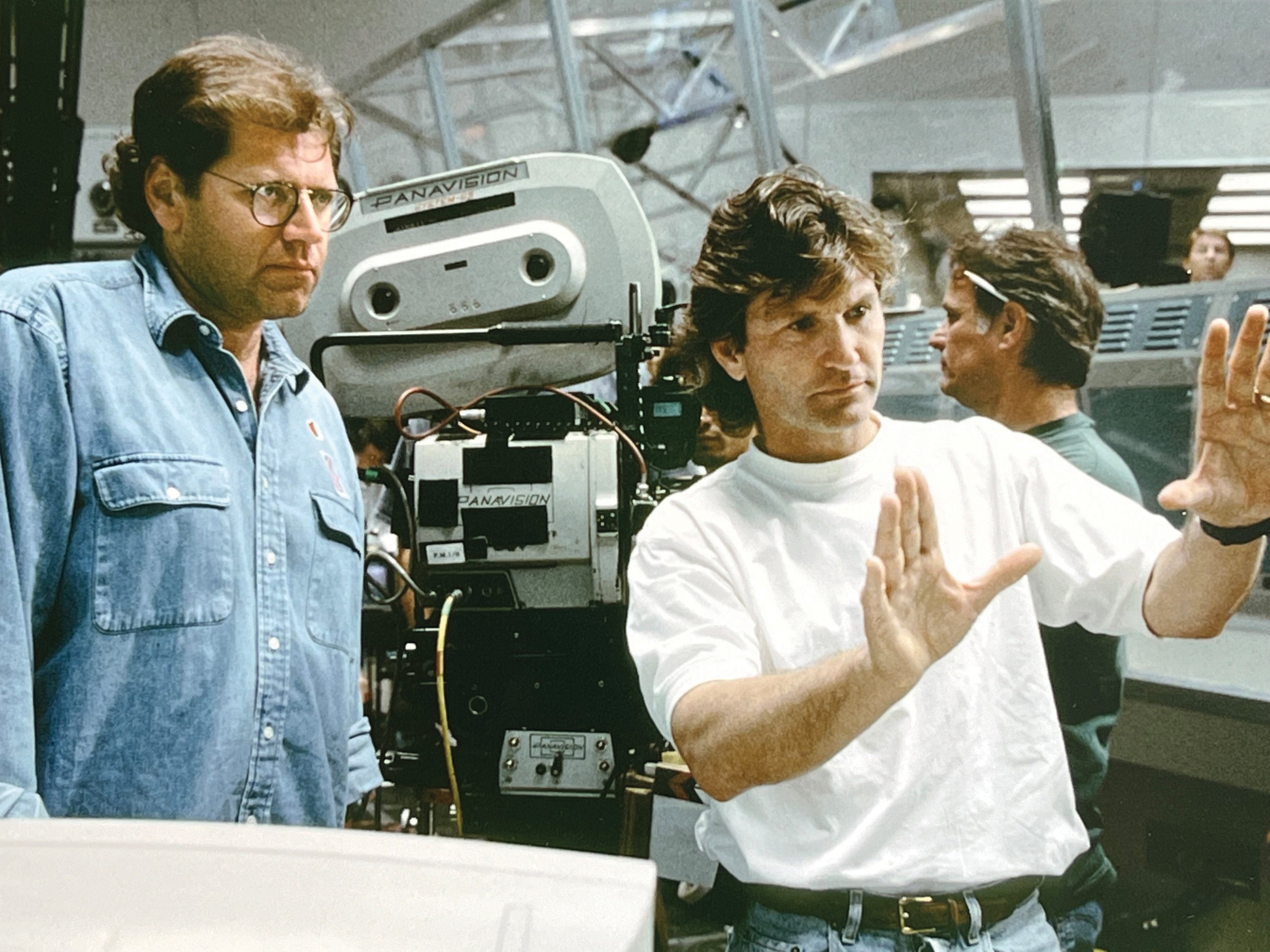

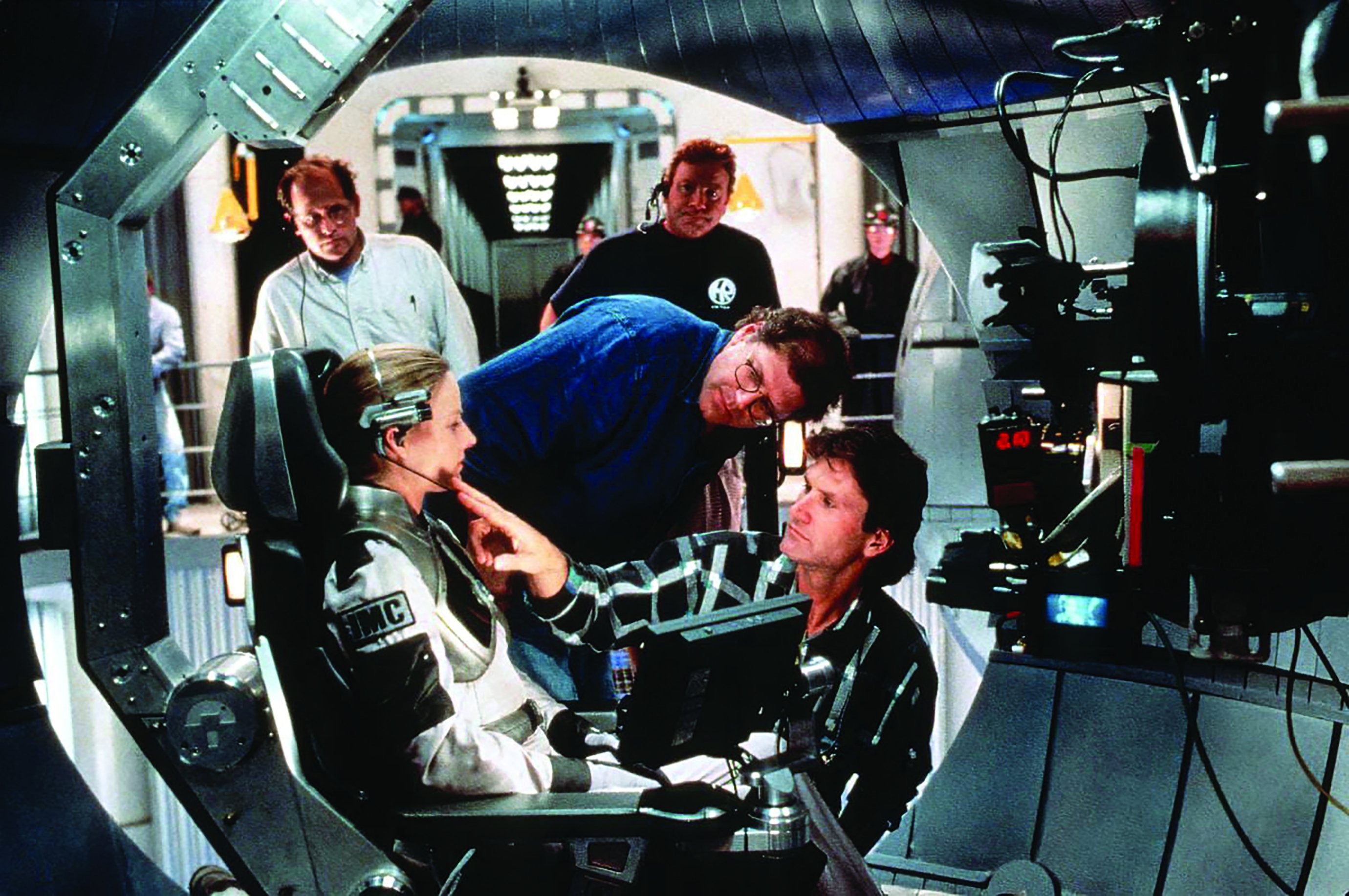

That reunited him with Kleven, who hired him to shoot 2nd unit on Zemeckis’ Back to the Future II and III. Those gigs led to an offer to shoot an episode of Tales from the Crypt for Zemeckis. Then, after Burgess returned to 2nd unit on Death Becomes Her, Zemeckis offered him the director of photography position on a little film called Forrest Gump (AC Oct. ’94). “When you’re working for people like Zemeckis, you feel that you’re part of the creative process, not just there to stand out of the way or follow the actor around,” the cinematographer says. “That’s a whole different kind of thing because of that invitation to participate in it, to use every tool in your toolbox to help him tell that story. He wants your instincts and your capability to troubleshoot, and that’s why our relationship has lasted more than 30 years. Bob believes I’m there to help him tell his story.

“[Forrest Gump] was a time in my life when I could take all the experience I’d earned along the way, bring it to the picture and have the confidence that I could run like the wind.”

“[Forrest Gump] was a time in my life when I could take all the experience I’d earned along the way, bring it to the picture and have the confidence that I could run like the wind. Halfway through the production, seeing dailies, seeing it come together, we saw that Bob was making something that no one had seen before. There was something special about it. I got to relax a bit; I got comfortable in my own shoes and thought, ‘Yeah, I can do this job, and I love it. I can’t wait to do it again tomorrow.’

Priorities

A father of three and grandfather of eight, Burgess emphasizes how important family has been throughout his life and career.

“My father passed away before Forrest Gump was released, but my mother was alive, and I wrote her a letter and thanked her for my life and the opportunity to do what I ended up doing. To have [that] support in the early years, when no one else believes in you except your parents … they ultimately help you make your dreams come true. I found this passion in high school, but you never know if it’s going to work out. You keep pursuing and pushing your boundaries and your limits, and you never know if you’re going to get to that point. There’s a lot of luck involved, and you have to have tremendous passion to keep pursuing beyond all the obstacles.

“Forrest Gump opened doors, but along the way I learned that the career isn’t just about the movies I want to shoot, but about the family I’m raising and a career. I truly believe that you can only be crazy enough to go down that road if you’ve got the support. It worked out for me. My career has afforded me the ability to live in a community where my kids can go to good schools. I was able to get attached to some wonderful projects and also have a family. I tried to be as versatile as possible with a commercial career, documentary career, 2nd-unit career — and I was able to eke out a living and be choosy about what I really put my passion into. They can’t all be gems, and you try and keep yourself available for directors like Bob. Sometimes you have to stay away from work and take a risk and gamble that the project you’re holding out for will get made. Sometimes it works out, and sometimes it doesn’t and you have to scramble.”

Following his breakout years with Zemeckis, Burgess was enlisted by directors such as Sam Raimi, Duncan Jones, Albert and Allen Hughes, and James Wan, serving as director of photography on Spider-Man, The Book of Eli, Source Code and Aquaman, as well as its sequel, Aquaman and the Lost Kingdom.

Reflecting on some of these experiences, Burgess says: “With Sam Raimi, it was a great challenge to create the visual language of the first feature-film version of Spider-Man, and it was the first movie to make more than $100 million in its opening weekend.

“The Book of Eli, with the Hughes Brothers, was my first digital film, shot with Red One, Build 16. Albert pushed the production toward shooting digitally, and we were given the opportunity to test extensively to come up with the post-apocalyptic look of the film. James Wan is a creative genius — a master of horror and superhero films and a pleasure to work with. For his films, I loved setting up and lighting cinematic shots for the grand scale of the big screen. And 8 Below, [starring] Paul Walker and directed in the frozen north of British Columbia by Frank Marshall, took me back to my adventure-documentary days of shooting in remote locations and extreme weather conditions.”

Burgess’ wife, Bonnie, has been by his side for 41 years, but she caught his eye much earlier. “We met when I was about 9 years old. Her father was the Pop Warner football coach, and she’d come down to the workouts to watch her brother play. I was trying out for quarterback, and the ball got loose. Bonnie picked it up and threw a perfect spiral back to her father, and he goes, ‘See, boys? That’s how you throw a football!’ We were friends for many years and got married when I was 26.

“I was very fortunate to fall in love with a woman who could actually deal with all this, and it’s no easy task,” he continues. “Ultimately, my family is the most important thing to me; without them none of this would have been worth it. Because of my wife and her support, I had the chance to develop the career I have … through missed birthdays and packing up the kids to go to yet another movie shoot somewhere. She is my rock. She’s the one that makes sure the machine keeps working while I run off and chase windmills.

Somewhat to Burgess’ surprise, his son, Michael, has followed in his footsteps. “I never thought my son would actually go into the movie business [because] he didn’t seem interested in it growing up. But he came out of film school and started working with me as a DIT and on-set colorist on movies like The Book of Eli. Now he’s shot six feature films, the last being The Family Plan with Mark Wahlberg. He’s off on his own.”

The ASC Family

Burgess became a member of the ASC in 1995 after his name was put forward by Steadman, Jack Green and Mikael Salomon.

“The ASC is an organization that I’ve always believed in and always been proud to be part of, and this award — to have the respect and recognition from my fellow cinematographers — means a lot to me,” he says. “The cinematographers ahead of me were always very kind and accepting of me in this organization, making me feel like I belonged.

“I’m proud of the work I’ve done. Ultimately, the cinematographer is the one who has to make the shot work. We have to love what we do and be able to say, for better or worse, ‘That’s it, that’s the shot.’ I’m proud that I’m still here and still enjoy the process, and each day I look forward to going to work to create some magic that didn’t exist the day before.”