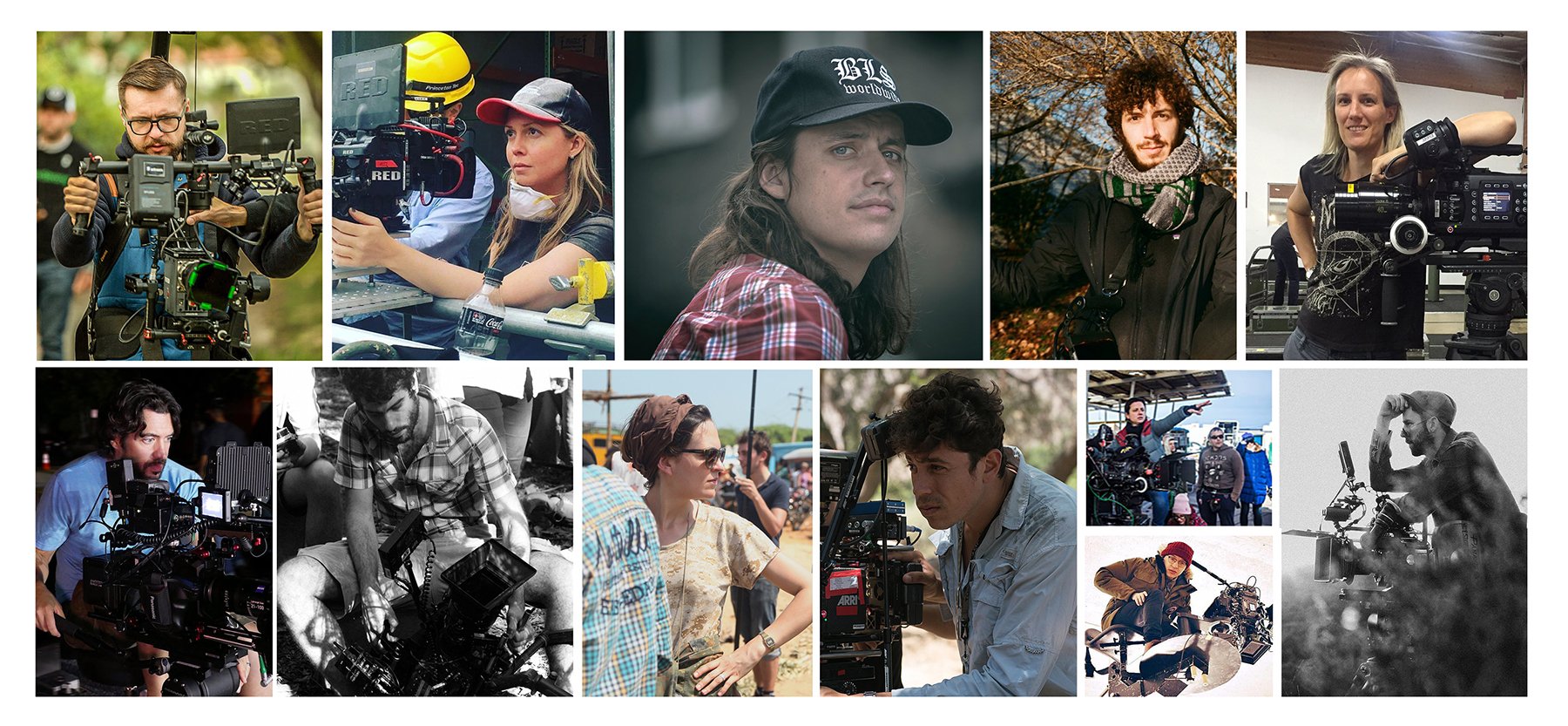

Rising Stars of Cinematography 2018

As part of a special focus report, American Cinematographer profiles 12 directors of photography who are making their mark.

Profiles by John Calhoun, Jim Hemphill and Debra Kaufman

To select this year’s list of Rising Stars, AC’s editors surveyed a wide field of excellent work shot by up-and-coming directors of photography. Eli Born, Carolina Costa, Johnny Derango, Ming Jue Hu, Matthias Koenigswieser, Rafael Leyva, Laura Beth Love, Nicola Marsh, Éponine Momenceau, Egor Povolotskiy, Michal Sobocinski and Adolpho Veloso have already begun to amass impressive credits in commercials, music videos, shorts, television series, documentaries and narrative features, and those credits promise tremendously bright careers ahead. As these stars continue to rise, we capture a snapshot of their trajectories to date.

Eli Born

It was camera movement, rather than lighting, that first drew Eli Born to cinematography. “I always loved the way the camera moved,” he says. “I didn’t know lighting was involved at all.”

Born began making his own movies at the age of 12, directing action films in his backyard. He looked not to other filmmakers but to his father as a role model. “He is a carpenter, and watching him methodically plan out a project and put it together piece by piece was very influential for me,” Born recalls. “The patience and focus required were always deeply admirable.”

While attending the Savannah College of Art and Design in Savannah, Georgia, Born formed relationships that eventually led to the acclaimed thriller Super Dark Times, which has garnered attention for its vivid period detail and haunting atmosphere. “I was lucky to find collaborators that I’ve grown with over the years,” he says.

Among his classmates was Kevin Phillips, the director of Super Dark Times and a cinematographer himself. Born notes that Phillips’ aesthetic tastes are right in line with his own: “He always wants the camera to move with the story. If there’s a new insight or emotion [introduced] in the scene, he wants the camera in a different place.”

Super Dark Times has received particular accolades for its night exteriors, which Born says were a challenge. “I had no big lights on the movie, so night exteriors had to be more about sculpting the background with highlights of color [surrounded by] shadow,” he explains. “Fortunately, we used Cooke Anamorphics, which had a beautiful bokeh I could play with.”

He adds that Super Dark Times was photographed in the precise narrative style he prefers. “We shot everything very deliberately. We used one camera and were extremely careful not to shoot coverage, instead using the story and characters to dictate the lensing and atmosphere.”

Born has many ambitions for the future, including shooting a big sci-fi movie and working more extensively at the crossroads between lighting and visual effects. “I’m excited by LED technology and the ability to bring color complexity and moving lights into studio and greenscreen work,” he says. “I hope to see more composites of practical effects and high-speed photography in the big visual-effects films we watch. There’s nothing comparable to seeing the real world in motion.”

In the pursuit of his goals, the cinematographer keeps his attentions on working and building relationships. “You can make anything look visually exciting, but the experience of making the thing feels more and more important as I get older,” he explains. “It’s all about community.”

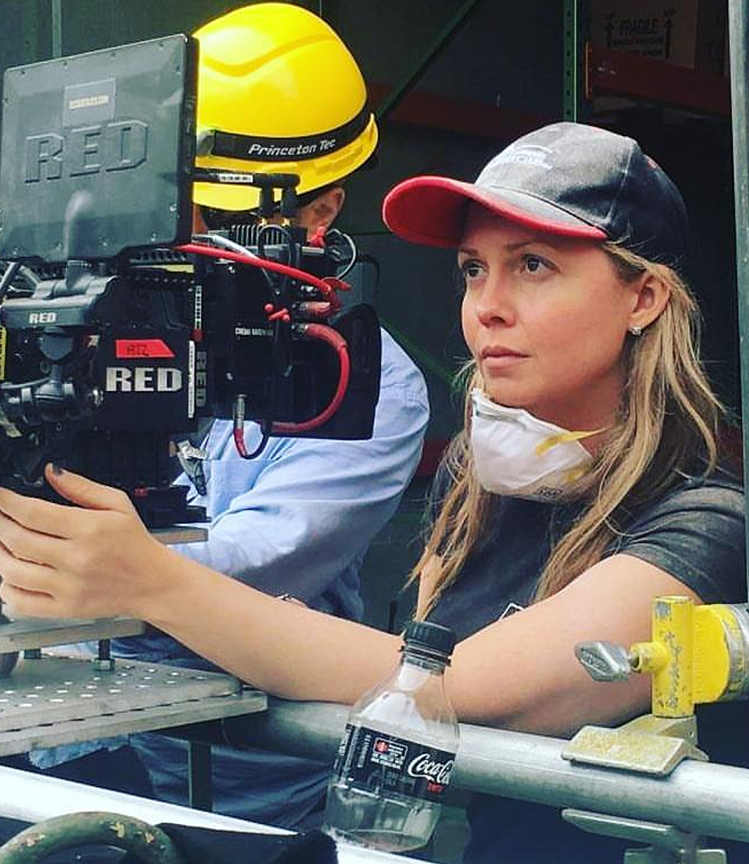

Carolina Costa

The Chosen Ones, Carolina Costa’s first feature as a cinematographer, premiered at the 2015 Cannes Film Festival in competition for Un Certain Regard, and went on to win five of the Mexican Academy of Film Arts and Sciences’ Ariel Awards, including Best Cinematography. But Costa’s success was hardly made overnight.

She began her career as a still photographer in her native Brazil. “When I was 15, I was already working with a photographer, from his lab in the back of his house,” Costa recalls. “That’s where my passion for images started, in that lab. I got my first camera and went around shooting, and I learned the basics about exposure and composition.

“I ended up moving to London in 2005,” she continues, “and I went to the University of the Arts. I started working as an assistant in the camera department very quickly. I never stopped to think about it; it was just very clear in my mind that I wanted to be a cinematographer.”

Costa was mentored by the late Sue Gibson, BSC, who was the first female member — and later the first female president — of the British Society of Cinematographers. “She moved from being a clapper-loader right into being a cinematographer,” Costa recounts. “She told me to go after what I wanted, and that’s what I did. I stopped answering the phone calls to second AC.”

She shot music videos and short films but felt like she was “hitting a wall” in her career until she applied and was accepted to the American Film Institute. “I was reborn in a way,” Costa says of her time at AFI. “Technically, I extended my bag of tools tremendously, which is so important. It also made me trust my instincts, and that is the tool I use the most.”

Contrapelo, an award-winning short she photographed right after AFI, led to The Chosen Ones, a sex-trafficking drama that was directed by David Pablos and shot on location in Tijuana, Mexico. “I had six weeks of prep to spend in Tijuana,” says Costa. “I shot-listed in every single location with the director, and built the lighting style based on my experience there. It was made in the right way.”

Since shooting The Chosen Ones, Costa has photographed the features Flower, They, Crystal Swan, Icebox and Hala in quick succession, in locations ranging from Chicago to Minsk. On her docket are a Brazilian miniseries and two more features in Mexico, including Pablos’ next film.

“I feel extremely lucky that I can handpick the projects I shoot,” says Costa. “First of all I need to connect with the script, and then I need to connect with the director. I’m mostly collaborating with young or first-time directors, and that allows me to grow with them, to create something together.”

Johnny Derango

Johnny Derango never planned to make films — he intended to study criminal justice. “Growing up in a small town, I had never thought of film as a career,” he reflects. With a laugh, he adds, “I mean, really, who makes movies for a living?”

His parents, though, encouraged him to follow his passion, and he wound up attending the film school at Columbia College Chicago. There, he was mentored by the late Ronn Pitts, and he photographed dozens of 16mm shorts. These experiences prepared him well for the work that awaited him in Los Angeles, where he found his break when he was hired for five days of reshoots on a 35mm feature. “The producers were so happy with my work they decided to reshoot 70 percent of the film,” he remembers. “I received my first feature director of photography credit, and the film debuted at the 2006 Tribeca Film Festival.”

That opportunity led to a network pilot, more television and feature work, and, most recently, to the darkly comic thriller Small Town Crime, which reunited him with the writing-directing team of brothers Eshom and Ian Nelms. “All three of the features we have done together have been very different visually and tonally, but with this one I was really able to add my visual stamp,” Derango says. “There are sections of the film that visually give the feel of a Rockwell-esque small town, but I was also able to craft a darker, grittier look to show the underbelly of the community.”

In achieving his vision for the project, Derango was especially focused on the choice of lenses. “Early on, I considered using vintage Cooke Speed Panchros,” he says. “I had already made the decision to shoot on the Sony F55, so I wanted to pair it with glass that would add some character. However, we were trying to stretch a tight budget, which included two full camera packages, so I opted for [Cooke] Mini S4s. I felt that the ‘Cooke look’ was a perfect juxtaposition to the gritty underbelly of this small town.

“While prepping,” he continues, “I decided that I was going to push the F55 to an ISO of 2,000 to try and introduce a bit of texture into the image. In doing so, I knew I’d be okay with the Minis’ slightly slower stop of T2.8. Also, with the Mini S4s having such a large range of lenses, it allowed me to split one set between my A and B cameras. The image was gorgeous. It was the best decision I could have made for this particular project.”

Ming Jue Hu

When Ming Jue Hu emigrated from Tianjin, China, to New York as an eighth grader, he fell in love with movies for a very practical reason: they helped him learn to speak English. After gorging on films rented from his local Blockbuster, Hu enrolled in a high-school cinema-history class. “In the class, I was exposed to films from old masters such as Hitchcock, John Ford and Billy Wilder, and modern auteurs like the Coens, David Fincher, Tarantino and P.T. Anderson,” he recalls, adding that Run Lola Run ultimately inspired him to apply to film school. “I was electrified by its energy and ingenious use of film language.”

Hu attended the New York University Tisch School of the Arts as an undergrad and immediately began crewing on older students’ shoots. Under the guidance of camera and lighting professor Geoffrey Erb, ASC, Hu began shooting short films during his final two years at school.

After graduation, Hu focused on shorts, music videos and commercials to build his reel. He broke into features when a fellow NYU grad asked him to shoot a film called M Cream in India. “I prepped for it for six weeks, and we shot in 44 locations from Delhi to the Himalayas in 54 days straight,” he remembers. “By Indian industry practice we didn’t really have any days off. I was 23 at the time, so it was very challenging to work with seasoned professionals from the Bollywood industry.”

M Cream won Best Feature at the Rhode Island International Film Festival and Best Cinematography at the Madrid International Film Festival, and gave Hu a new level of confidence. “The experience of that film encouraged me to continue to pursue cinematography,” he says. “It was the start of a crazy adventure.”

Hu has gone on to shoot a number of ambitious projects, including the sci-fi romance Fatal Love, for which he found inspiration in the work of two of his heroes, Roger Deakins, ASC, BSC and Robert Richardson, ASC. “Deakins tends to light with strong motivation from light sources to create an enhanced reality,” Hu explains. “Richardson tends to light purely based on emotion and psychology. I tried to blend these two approaches in Fatal Love, and I feel I achieved a good balance between realism and expressionism.”

Hu plans to reunite with Fatal Love director Haolin Song in 2018, but first he’s shooting a love story set in Shanghai that Wong Kar-wai is executive producing. “The director is Cheng Xiaze and the male lead is one of my favorite Asian actors, Chen Chang,” he says. “Wong Kar-wai is a childhood hero of mine, so I’m excited for this opportunity.”

Matthias Koenigswieser

Although director of photography Matthias Koenigswieser has recently completed a big-budget fantasy film — the Disney-produced, Marc Forster-directed Christopher Robin — it was the documentary impulse that first inspired him to pick up a camera. “My interest in filmmaking came from a sudden urge to document my daily life when I was around 13,” he says. “I was born and raised in Vienna, but I lived in the country for three years due to my mother’s work at the local hospital. Spending my days in the forest, running across frozen streams and wide-open fields, and being one with the elements inspired me.”

Koenigswieser carried a JVC VHS-C camcorder to document those everyday moments, yet he still had no aspiration to go into filmmaking professionally. “After high school I actually enrolled in culinary-arts school,” he says. He planned to become an international chef — until he wandered into a cinema and saw Darren Aronofsky’s Pi. “I loved [ASC member] Matthew Libatique’s intense, beautifully grainy black-and-white reversal photography,” Koenigswieser recalls. “I never went back to cooking school. I decided to leave Austria behind and study film. Buying that movie ticket was the best decision I’ve ever made — it changed everything.”

Koenigswieser attended the Academy of Art University in San Francisco, where he trained with 16mm and 35mm cameras. “The digital revolution happened just as I finished school,” he explains. “Learning on film was invaluable and still informs the way I treat digital in terms of aiming for the most organic final product.”

After film school, Koenigswieser operated for Stoeps Langensteiner and Christopher Probst, ASC, all the while honing his skills as a director of photography, building his reel, and looking for the right director with whom he could grow. He found that director in Forster, who hired Koenigswieser to shoot the Hand of God pilot for Amazon. That led to a collaboration on the independent feature All I See Is You, which received a Best Cinematography Debut nomination at Camerimage.

Koenigswieser says Forster’s sensitivity to character and naturalism is right in tune with his own sensibilities. “My camera is moved by the performance in the scene,” he explains. “It can translate emotion as subtly or grandly as the moment demands.”

The success of All I See Is You led directly to Christopher Robin, Koenigswieser’s first studio feature, which he has found to be surprisingly liberating. “I kept waiting for someone to force me to do things differently, but it never happened,” he says. “The whole experience certainly has been the highlight of my professional life so far.”

Rafael Leyva

When he was 8 years old, Rafael Leyva and his family gathered around a new television to watch Jaws. “I wasn’t scared,” he recalls. “I was more intrigued by how my family members got scared and reacted to the movie.”

By the time he was a teen, he was haunting the aisles of his local Blockbuster, and he’d started breaking down movies in notebooks. When his best friend moved to New York to attend NYU, Leyva followed, though he couldn’t afford to attend. In the fall of 2004, he crashed a cinematography class and, he recalls, “It clicked. I’d found what I wanted to do for the rest of my life.”

He was working odd jobs to pay the bills, and in his free time he would go in search of production trucks and whatever gigs he could find on set. His tenacity paid off when a 1st AD hired him as a production assistant, which led to a slew of similar jobs.

After moving to Los Angeles, Leyva was at a Hanukkah party when he met “a wonderful gentleman wearing a Panavision sweater,” he recalls. It was ASC associate member Andy Romanoff, whom Leyva credits as his first mentor. “I learned to become a man from him,” he says. “I learned about the industry and the political side of being a cinematographer.”

By then, Leyva was spending time on sets, taking behind-the-scenes photos he’d give to the crew. He also wrote a fan letter to Paul Cameron, ASC, who invited him to meet for breakfast. After that, Leyva shared everything he shot with his Canon DSLR with Cameron, who invited the aspiring cinematographer to shadow him on the set for two years. “Paul has been the biggest influence in my artistic career,” says Leyva, adding that his time with Cameron “was the best, most hard-core experience I’ve had [in which] to learn.”

In 2014, Leyva enrolled in an ASC Master Class. “It was the most beautiful experience,” he says. “I found myself with my peers, and people I respected and admired, like Bill Bennett, ASC and Dariusz Wolski, ASC. After 10 years, I felt like I was home.”

Right after the class ended, Leyva’s first big break came with an offer to shoot Nightmare Wedding, a feature for Lifetime Television. The project he’s most proud of so far is Last Rampage: The Escape of Gary Tison, directed by Dwight Little. “I learned the true professional film ethic that people have in the highest ranks of filmmaking,” the cinematographer enthuses. “The director knew exactly what he wanted, and he encouraged me to push the envelope. The incredible artistic trust made me better.”

Laura Beth Love

Cinematographer Laura Beth Love says that she’s always had a passion for painting and storytelling. She entered the University of North Carolina School of the Arts, where she pursued directing and writing. “I discovered very quickly that it didn’t matter what you wrote or directed if the person holding the camera and setting the lighting didn’t know what they were doing,” she says.

In the summer after her freshman year, she was hired as a production assistant on Juwanna Mann, a basketball comedy shot by Reynaldo Villalobos, who generously answered her questions about his work. “I was excited by the challenges he was having to solve,” Love recalls.

When she returned to school in the fall, she changed her focus. “It was the first time I said out loud that I wanted to be a cinematographer,” she says. She studied under her formal mentor, cinematography instructor Richard Clabaugh, as well as assistant dean of production David E. Elkins, author of The Camera Assistant’s Manual.

After graduating, Love moved to Los Angeles. She had been trained on film, but she was excited about the influx of new digital tools, especially the combination of Panasonic’s AG-DVX100 24p camera and P+S Technik’s Mini35 adapter. “I made that my workhorse,” she says. “I sold myself as the person who could give you the ‘film look’ on DV.”

After working as a gaffer and grip on a few shows, Love landed a job at a low-budget commercial company, where she booked her first professional gig as a cinematographer in 2003. “By 2008,” she recalls, “[digital cinema] cameras had become the norm, even in the indie world. I had to engineer opportunities to test and research that equipment. I’m so grateful for my traditional film training. I feel I’m able to marry that discipline and classic approach to storytelling with the flexibility and immediacy of digital cinema.”

As a freelance cinematographer or director, Love has worked on some 30 indie features to date. She recently joined Local 600 and completed her first union job, as B-camera operator on the Facebook series Five Points. She’s most proud of her work on Tabloid Vivant, The Horde and If Looks Could Kill. “All three of them had directors and producers who wanted to commit to the look,” she recalls. “I’m most excited to collaborate with directors who have a clear vision and the passion to pursue it. By combining traditional and modern approaches, we can accomplish anything.”

Nicola B. Marsh

When she was 14, Nicola B. Marsh discovered her love for photography. “I would conceptualize but couldn’t draw,” she says. “Photography and the darkroom really gelled for me. I am a physical person and a physical learner, and the physical craft of pictures aligned with that.”

After finishing college in the U.K., she worked as a camera assistant on commercials and indie features in London, then moved to the U.S. She landed in San Francisco, where she shot news for the NBC affiliate. “It was really good practice to have your eye on a camera every single day of the week, and then have to edit everything you shot, with a deadline,” she says. “I started work at 10 a.m. and had to shoot and cut a package by 5 p.m.”

By her third year shooting news, however, she was ready for a change. She entered the cinematography program at the University of Southern California, where School of Cinematic Arts associate professor Christopher Chomyn, ASC became a mentor. “He was a great teacher,” Marsh says. “He’s really interesting and nurturing. He was there to pick up my phone calls after school, and he extended his contact list to me.”

Through her USC connections, Marsh met director Morgan Neville, for whom she photographed the documentary Search and Destroy: Iggy & the Stooges’ Raw Power. Marsh and Neville continued their collaboration with the documentaries Troubadours and 20 Feet From Stardom, the latter of which won the Oscar for Best Documentary Feature. “It was a slow incline,” she says, “but 20 Feet made the biggest difference in terms of having shot a film that people had seen or heard of. Working hard and getting lucky eventually overlap.”

Indeed, noting that there are many definitions of a “first break,” Marsh also highlights her experiences shooting Eye of the Hurricane in Georgia. “It was my first ‘real’ $2 million feature,” she says. And she’s proud of her work on the documentary Burn, for which she followed a Detroit fire department over the course of two years. “We had more footage than you could dream of, because they have 15 to 25 fires a night,” she says. Burn went on to win the 2012 Tribeca Film Festival Audience Award.

Shooting the Netflix documentary series Chelsea Does, starring Chelsea Handler, presented other challenges altogether. “Working with celebrities means there’s a higher bar for the aesthetics,” Marsh offers. “But it’s a documentary, so you want to make sure the talent has total freedom to move anywhere they want. You can’t light them into a corner.” At press time, Marsh was prepping a documentary with director Clay Tweel.

Éponine Momenceau

Having studied piano and harp for years, cinematographer Éponine Momenceau sees her current work in motion pictures as existing on a continuum with her music. “Learning to make pictures with a camera was like learning a new instrument,” she says. “It’s an instrument I can play to express a language — a vision of a world in movement.”

Once she decided on a cinema career — after also studying math and physics — Momenceau enrolled in the Paris cinema school La Fémis, where she spent the next four years “learning much more than the technical aspects of cinematography,” she says. Thanks in part to the experimentation and collaboration the school encouraged, “I had this feeling when I exited school that I was looking differently at things and at myself.

“Of course, the experience of learning continues after school, with new encounters, new collaborations,” she continues. “I envisage each project as a new field of experiments to which I bring all I have stored from my previous experiences.”

Since graduating in 2011, much of Momenceau’s work has been in the realm of experimental cinema or visual art. She shot Before Music There Is Blood for an installation with the band Soundwalk Collective. She also created the 10-minute video Waves Become Wings, which was exhibited at the Palais de Tokyo, among other sites.

When director Jacques Audiard saw Waves Become Wings, he approached Momenceau to shoot the feature Dheepan, a drama about a Tamil immigrant in Paris. Audiard’s improvisatory style and openness to ideas — from his cinematographer as well as the actors — were a tonic to her. “We had a very free way of sharing, and it liberated me,” she reflects. Dheepan was her debut feature, and her work was recognized with a César nomination. “It’s funny — when I entered school, at the final oral in front of 10 people in the profession, they asked me to name the French directors I wanted to work with, and I answered, ‘Jacques Audiard.’ It’s done now.”

Momenceau also points with pride to Princes Among Men, a documentary about the Roma people and their music, which she shot over a year and a half in six Balkan countries with director Stephan Crasneanscki of Soundwalk Collective. Coming up, she has another video and sound installation with Crasneanscki’s band, a film with Stephen O’Malley and the musicians of Sunn O, a feature for Chinese director Wang Quan’an, and a documentary with Jean-Stéphane Bron.

It’s the “alchemy” between director and cinematographer that is most important to Momenceau. “The work of the cinematographer doesn’t exist without the imagination, the mind, and the spirit of the director,” she muses. “Sometimes I feel that a cinema crew during shooting is like an orchestra, and the director is like a conductor.”

Egor Povolotskiy

While working toward a degree in artificial intelligence at the Moscow Engineering Physics Institute, Egor Povolotskiy came to a realization: “I was more interested in photojournalism,” he says. So, after graduating, he started taking photos for a Russian news agency and the Russian Association of Motorcyclists.

When that association’s president, Alexander Kisel, invited Povolotskiy to come to a film shoot to take behind-the-scenes photos, “I started being interested in being on set in general,” he says. “I enjoyed the process.” As his interest in filmmaking grew, he was offered a job as a cinematographer on a feature — but he had to decline. “I had no experience as a director of photography at all,” he reflects. “It’s not just shooting, but visual storytelling and being the head of the department.”

With the encouragement of his wife and parents, he moved to Los Angeles in 2013, to attend the New York Film Academy. About that time, he recalls, “I said, ‘I don’t know anybody, and I have no connections. What will I do there? How will I survive?’ And my wife said, ‘Just go, and it will happen.’”

Line producer Mariietta Volynska, an alumna of NYFA, saw a screening of Povolotskiy’s thesis film and offered him a job right out of school to shoot the horror feature Bornless Ones, directed by Alexander Babaev. “Now I am on my eighth feature film and around 60 shorts as a cinematographer,” says Povolotskiy, who credits Mike Williamson, the associate chair of cinematography at NYFA’s L.A. campus, as a mentor.

Another significant break came with the opportunity to shoot his first feature with well-known actors: director Kayla Tabish’s Culture of Fear, starring Malcolm McDowell and Steven Bauer. Povolotskiy also highlights the comedy feature Gold Dust, directed by David Wall. “We shot in the Mojave Desert, and we lived together in one house,” the cinematographer notes. “Every evening we gathered by the table, discussing and laughing. It was an amazing experience of collaboration and friendship.”

Povolotskiy credits much of his success to those surrounding him. “You are as good as your crew,” he says. “I get huge support from my whole crew, especially gaffer Kevin Kim; first AC Eugene du Plessis; and Ara Thomas, my equipment person, who is always with me. They believe in me — and they’ve suffered a lot to take our work to the best level possible!”

As this issue goes to press, Povolotskiy is prepping River Runs Red, directed by Wes Miller and starring Taye Diggs, John Cusack and George Lopez — as well as an upcoming project with director Cyril Zima. About the latter, he teases, “It has a very interesting approach to storytelling. I don’t want to spoil anything, but it’s going to be unique!”

Michal Sobocinski, PSC

One could say director of photography Michal Sobocinski, PSC comes by his craft honestly. His grandfather, Witold Sobocinski, PSC, worked as a cinematographer for Andrzej Wajda and Roman Polanski on projects including The Promised Land and Frantic, respectively; his father, the late Piotr Sobocinski, PSC, received an Oscar nomination for Polish compatriot Krzysztof Kieslowski’s Three Colors: Red; and his brother, Piotr Sobocinski Jr., PSC, is also an accomplished cinematographer.

“Whenever my dad shot a film, we would go with him,” says Sobocinski. “I was raised on the set, next to the camera. But my dad didn’t want to push us. I wanted to be a guitar player, and I got a guitar from him.” When he realized that his talent for music was not what he hoped, “I naturally started doing photography and preparing for film school. I think there was no other way for me — it’s my life, my dream job.”

Sobocinski attended the renowned Polish National Film School in Lodz, where his 88-year-old grandfather still teaches. “I had him as an instructor, and he was tough,” says Sobocinski. “But he’s the best professor because he’s very practical about things; it’s not all theory.”

After his first year in school, Sobocinski started operating on features and shooting commercials. During his third year, he shot his first feature, Kamchatka, which became his thesis film and was nominated for Best Cinematography Debut at the 2013 Camerimage International Film Festival. He had previously won a Bronze Tadpole at the festival for his first-year student film, Father.

Sobocinski says he’s learned a great deal from the cinematographers for whom he’s operated, including Slawomir Idziak, PSC. “My biggest mentor, for whom I operated the most, was Krzysztof Ptak, PSC, who passed away last year,” Sobocinski says. “He was a very calm and modest man, and he taught me that. He was a great friend; I miss him very much.”

He considers his real breakthroughs to be Art of Loving — which won the 2017 Camerimage award for Best Polish Film — and another film he shot last year, Konwój. With those projects, he explains, “I started to take more risks. The Art of Loving is a biopic, but it’s told in quite high saturation and contrasting colors, and in master shots with wide lenses. I’m crazy about camera movement, so that’s why I prefer wider lenses; you can do master shots in long takes. It’s like making music. You have to feel when someone comes in, when the camera moves, what’s the proper proportion. It’s all about intuition and the proper rhythm.”

The result has not only been winning awards around the world, it has garnered the approval of the cinematographer’s toughest critic. “My grandfather likes the cinematography,” says Sobocinski. “And that never happens.”

Adolpho Veloso

Growing up in São Paulo, Brazil, Adolpho Veloso decided by age 12 that he wanted to be a filmmaker. “Before entering film school and before knowing exactly what the different roles were, I thought I wanted to be a director,” he recalls.

As he began to learn the process, however, Veloso soon recognized his true calling. “When I saw what the cinematographer did, I was like, ‘Oh, that’s the thing I want to do. To be close to the camera, blocking the scene, lighting — and also, of course, dealing with the actors, but in a different way. For me, it’s always about the story and the characters; that’s how I build my work with the camera and the lighting.”

Veloso’s steady rise — from production assistant, to shooting shorts and music videos while studying film at São Paulo’s Fundação Armando Alvares Penteado, to commercial work soon after graduation — coincided with the industry’s transition from film to digital acquisition. “At school I was photographing with film,” he recalls, “but when digital came, that opened doors to a lot of new people. I started doing commercials for great brands, and that caught the attention of my agent in L.A.”

After he was signed, he says, “I started working everywhere — Europe, Asia, North America.” A high point was shooting a Nike commercial for director Nicolas Winding Refn. “I’ve been a fan of his, so it was like, ‘Oh my God, we have a slate with both our names.’” Veloso has also made his mark in documentaries, one of which, On Yoga: The Architecture of Peace, earned him a 2017 Golden Frog nomination at Camerimage.

Still, narrative storytelling remains Veloso’s ultimate goal. His first narrative feature was Asco, in 2015, followed by the upcoming Rodantes, which he shot for director Leandro Lara in the western Brazilian state of Rondônia. “It’s probably the thing I’m most proud of,” the cinematographer says of Rodantes. “We had three main characters and decided to shoot each of them in a different way, with different lenses.”

Though Veloso draws inspiration from the work of cinematographers like Gordon Willis, ASC and César Charlone, ABC, and still photographer Miguel Rio Branco, he says that he was not mentored by anyone in particular. “Sometimes I miss that, but at the same time I think that’s why I don’t feel like I’m following any rules,” he concludes. “I never think to myself, ‘How would he light this?’ It’s always about what I can achieve with what I know, and not trying to follow someone else’s way of doing it. Of course, that makes me do it wrong a lot of times. But sometimes, I think, I get a good result.”