Game On: Game-Engine Technology Expands Filmmaking Horizons

“What directors want are iterations. They want to find all the possible challenges early, so the faster you can see a result, understand the issues and create another iteration, the better. Real-time engines make that process happen instantly. It’s just like playing a video game.”

The Mandalorian image by François Duhamel, SMPSP, courtesy of Lucasfilm Ltd. Cine Tracer image courtesy of Matt Workman/LED volume photo by Mike Seymour. The Lion King unit photography by Michael Legato, courtesy of Disney Enterprises, Inc. Game of Thrones image courtesy of HBO and The Third Floor, Inc.

Game engines such as Unreal Engine and Unity were, as their umbrella term implies, originally designed for the development of real-time applications, aka video games. In recent years, advances in both hardware and software have ushered these engines into the purview of cinematographers. Game engines are now used to create many forms of visualization for filmmakers, including previs, techvis and postvis — and even final in-camera movement and imagery for such productions as The Lion King (AC Nov. ’19; see sidebar below) and The Mandalorian (AC Feb. ’20).

Traditional 3D animation applications such as Autodesk’s Maya and 3ds Max have long played a significant role in visual effects. Their comparatively slower performance, however, has seen their benefit focused more on pre- and postproduction, where time is somewhat less critical than in live-action production. These 3D apps prioritize final image quality over performance; as a result, image render times can easily stretch into hours or even days per frame, depending on the complexity of the shot and the computational power of the hardware.

By contrast, game engines were initially optimized for speed first and image quality second, in order to support gameplay in real-time, often at frame rates of 60 frames per second or more. And in the past few years, major technical advancements in the graphics-processing unit (GPU) of computers have enabled such engines to render production-quality imagery while maintaining their real-time speed.

Commensurate with these hardware improvements, developers such as Epic Games (creators of Unreal Engine) and Unity Technologies (creators of Unity) have optimized their software for direct inclusion into the production pipelines of features and television. These changes are intended to support the crossover between traditional cinematography and computer-generated imagery — a dynamic that can serve filmmakers in a whole host of ways.

Matt Workman, a cinematographer and software developer, is working to erode even further the boundaries between filmmaking and CG with his creation of Cine Tracer, a real-time cinematography simulator built with Unreal Engine. The application — offered directly to filmmakers — enables the viewing of real-world camera and lighting equivalents in simulated, user-designed movie sets to produce highly accurate shot visualization.

“My background includes about 10 years of traditional cinematography, mostly in commercials around New York City,” Workman says. “During that time, I worked with a lot of visual-effects companies on effects-heavy commercials — so I started creating previs tools to communicate in 3D and plan with the teams. A couple of years ago, I started developing Cine Tracer to handle that workflow more efficiently. I [designed] it as a video game [that’s controlled similarly to playing a third-person shooter game], but it’s intended to help filmmakers quickly visualize their shots.

“I went to school for computer science, but I’ve always been tinkering with 3D,” he says. “Luckily, it’s 2020 and there’s YouTube, so the amount of available free education is incredible, as long as you have the time and the patience to learn.

“Most cinematographers who are on the technical side pick up [game-engine-powered previsualization] very quickly. If you want to add light coming through the window, the steps to get there are very quick. It’s the same way you do it in the real world.”

Regarding the primary advantage that real-time engines have over the more traditional computer-animation software, Workman notes, “The iteration time is much faster. If you want to see a camera move [for a specific shot] in order to determine, for example, what it would look like if you start close and then pull out wide — to see that change with Maya, you’re taking up to a couple of hours to render maybe 120 frames at high quality. In Unreal, that change happens instantly.”

Visualization studios like The Third Floor have leveraged Unreal and other real-time engines on projects for the past several years to design previs, techvis and postvis services, and other forms of animation used in various phases of the production chain. The Third Floor’s credits span multiple Marvel movies, The Rise of Skywalker, (AC Feb. ’20) and other recent Star Wars films, as well as popular episodic series such as The Mandalorian and Game of Thrones (AC May ‘12 and July ‘19).

Casey Schatz, The Third Floor’s head of virtual production, has worked on such projects as Thor: Ragnarok (AC Dec. ‘17), Gemini Man (AC Nov. ‘19) and The Mandalorian, and has helped innovate everything from flame-throwing motion-control robots to real-time virtual eyelines.

In addition to the obvious benefits of real-time rendering, Schatz, sees these software and hardware innovations as facilitating greater direct collaboration between studios like The Third Floor and cinematographers. “Historically, as previs creators, we were brought in very early, often before the DP was even hired,” he says. “So a certain amount of work had already been done, and when the cinematographer finally came on, they often felt like they were just painting by numbers. No one in visual effects wants that approach. We’re all trying to blend in with the wheel of filmmaking that’s existed since the Lumière brothers.

“Just a few years ago, game engines weren’t as conducive to moviemaking. Unreal’s virtual camera didn’t have a focal length or a film back [aka aperture gate] — it just had a field of view. Now there’s focal length, film backs, depth of field, f-stops, ISO and shutter speed. Epic even added the ACES color workflow into the rendering pipeline.

“A respect for and acknowledgment of traditional filmmaking has made its way into the software,” Schatz adds. “So you can say, ‘I’m shooting anamorphic with Panavision Primos,’ and we’ll have a menu of those exact focal lengths so that you can’t previsualize a focal length that doesn’t exist in your real lens kit.

“The goal has always been that even someone that has never touched a computer before, but is a remarkable cinematographer, can sit down next to a computer artist and talk in the language that they’re comfortable with — f-stops, T-stops, shutter speeds, film ISOs, grain, bounce light, diffuse light — the traditional cinematography terms that have existed for more than 100 years.” — Casey Schatz, The Third Floor’s head of virtual production

“I’m working on the Avatar sequels now using Gazebo, Weta Digital’s proprietary real-time engine,” he says. “Russell Carpenter [ASC], the movies’ cinematographer, sat down with the lighters before we did any of our live action in New Zealand. Together they set the tone, the mood, the general key-light direction, the key-to-fill ratio, et cetera; all of this was done using [cinema terminology] Russell is accustomed to. Thus, the line in the sand between traditional cinematography and computer graphics is disappearing more and more every day.”

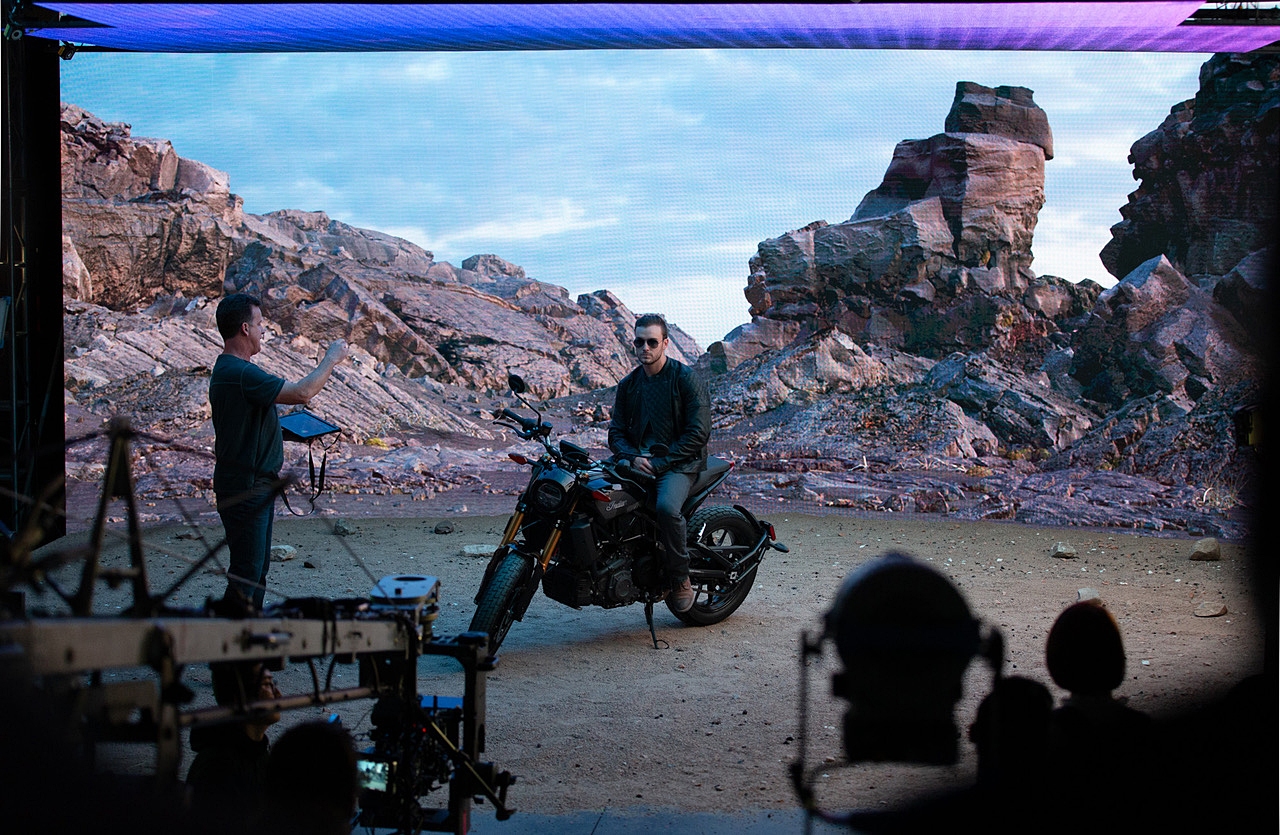

Indeed, the rendering time of high-resolution interactive imagery has advanced to the point that it can actually appear onscreen as-is or with minimal adjustments in post — as employed, for example, on The Mandalorian.“That was our goal,” said Greig Fraser, ASC, ACS (who shot the Disney Plus Star Wars series along with Barry “Baz” Idoine), as reported in AC’s February 2020 issue. “We wanted to create an environment that was conducive not just to giving a composition line-up to the effects, but to actually capturing them in real time, photo-real and in-camera, so that the actors were in that environment in the right lighting — all at the moment of photography.”

When asked which specific advancements in real-time engines have pushed forward their synergy with traditional cinematography, Schatz explains that the ability to simulate bounce light, something so fundamental to traditional cinematography, is a game changer because only recently could this happen in real time or even close to it. “[During a previs session] a traditional cinematographer could be looking at a shot and say, ‘If we put a Kino Flo 6 feet away and add a bounce card, what would be the result?’ We can now show that result very quickly and accurately. Prior to these advancements, computer lighting was more analogous to theatrical lighting; you could aim a light and cast a shadow, but then you would have to cheat a bounce light by adding other lights to the sides at lower intensities.”

One of Schatz’s Third Floor colleagues, real-time developer Johnson Thomasson (The Mandalorian, Venom, Godzilla: King of the Monsters [AC June ‘19]), is quite directly involved with the intersection of live-action cinematography and real-time animation — specifically via motion capture and “virtual-camera sessions.”

“One of the major benefits to real-time animation is ‘practice time’ for the filmmakers,” Thomasson says. “We worked on Christopher Robin, and director of photography Matthias Koenigswieser was able to use a virtual camera rig, playing back animation from the film and recording his camera motion so he could practice operating. He was able to directly experience the size difference between 12-inch tall Piglet and [for scenes set in the title character’s early years] 4-foot-tall Christopher Robin.

“It was a real challenge framing both of them, and something he hadn’t considered before coming to our virtual-camera sessions,” Thomasson continues. “It allowed Matthias to design his compositions ahead of the actual production. He was shooting with an empty frame [aka, a clean plate] on the day, but having rehearsed virtually, he already knew what the right framing felt like. When directors and DPs go through a virtual-camera session, they discover new ideas, and they’re exploring, expanding and coalescing their creativity.

“Another benefit is the physical representation of depth of field, which has never been rendered well in previs in the past,” Thomasson adds. “Unreal’s depth-of-field camera model is based on real-world cameras. So a cinematographer can ask which stop we’re at in a virtual-camera session and get an answer that reflects a physically accurate visual model. In my experience, when DPs learn about that capability, they want to take advantage of it, because depth of field is one of the strongest tools in their toolset for communicating their choices in cinematic language early on in preproduction.

“For directors who are not veterans of giant visual-effects tentpole films, it’s a new experience when they first get to the set. But [prepping] in a low-pressure, small-audience situation, and exploring and practicing via [real-time interactive previs], prepares them for the set like nothing else could.”

Looking toward the future, Schatz sees game engines becoming further entwined with live-action cinematography. “The hardware and software are going to [continue to advance], and it might almost become indistinguishable in terms of which imagery is real-time and which isn’t,” he says. “This is in service of the story and not to show off the technology. The motto of the Previsualization Society is ‘fix it in pre.’ The more creative decisions you can interactively figure out before you get on set, the better.

“The goal has always been that even someone that has never touched a computer before, but is a remarkable cinematographer, can sit down next to a computer artist and talk in the language that they’re comfortable with — f-stops, T-stops, shutter speeds, film ISOs, grain, bounce light, diffuse light — the traditional cinematography terms that have existed for more than 100 years.”

Workman adds, “What directors want are iterations. They want to find all the possible challenges early, so the faster you can see a result, understand the issues and create another iteration, the better. Real-time engines make that process happen instantly. It’s just like playing a video game.”

Game-engine technology can provide cinematographers with ways to previsualize in a simulated filmmaking environment — but it can also serve as a filmmaking medium in itself. With the aid of game-engine tech, veteran cinematographer Caleb Deschanel, ASC leveraged his extensive traditional cinematography experience to capture The Lion King with entirely virtual characters, and settings as well (save for a single shot). Making this possible was visual-effects supervisor Robert Legato, ASC and a team of technicians and artists at Magnopus, who coupled the Unity game engine with various traditional dollies, cranes, tripods and other camera-movement tools to enable Deschanel to manually operate virtual cameras while directly interacting with live animation.

“The essential thing for me in filming this way is having enough visual detail so I can make the same kind of decisions I always make on a set,” Deschanel tells AC. “That informs how you compose the shot and how you light it.” Though not yet photo-real — as the process to make them so would unfold later at MPC in London — the filmmakers’ subjects were imbued with enough detail by the real-time interactive system “that you can read their emotions and understand how close or how wide you need to be,” Deschanel says.

Legato — who was a key member of the virtual-camera crew in addition to his role in developing the technology — adds, “We’re essentially motion-capturing the Steadicam operator attached to the Steadicam or a dolly grip attached to the dolly. With the game engine, everything is live and under your control. You just walk over to the place that seems the most appropriate for you to film it. And because it’s live, you can say, ‘Let me get a little lower or a little higher, or let me try this same position with a 20mm instead of a 24.’ You’re tapping into your on-set intuition, which is ultimately years and years of experience, instead of overintellectualizing it.”

With these tools at their disposal, Deschanel and crew could not only capture the motion and composition of their virtual cinematography, but make visual design choices as well. “I would sit with [lighting director] Sam Maniscalco, who was my gaffer, with the files of all the sets,” Deschanel recalls. “We had a choice of 350 different skies to give us the right mood for every scene. It was just like being a cinematographer [in a traditional environment], but having far more control than you normally would. On a [traditional set], you don’t have control over the clouds and sky, so you have to follow the sun throughout the day. It was exciting and a lot of fun — I was really surprised.” — Noah Kadner