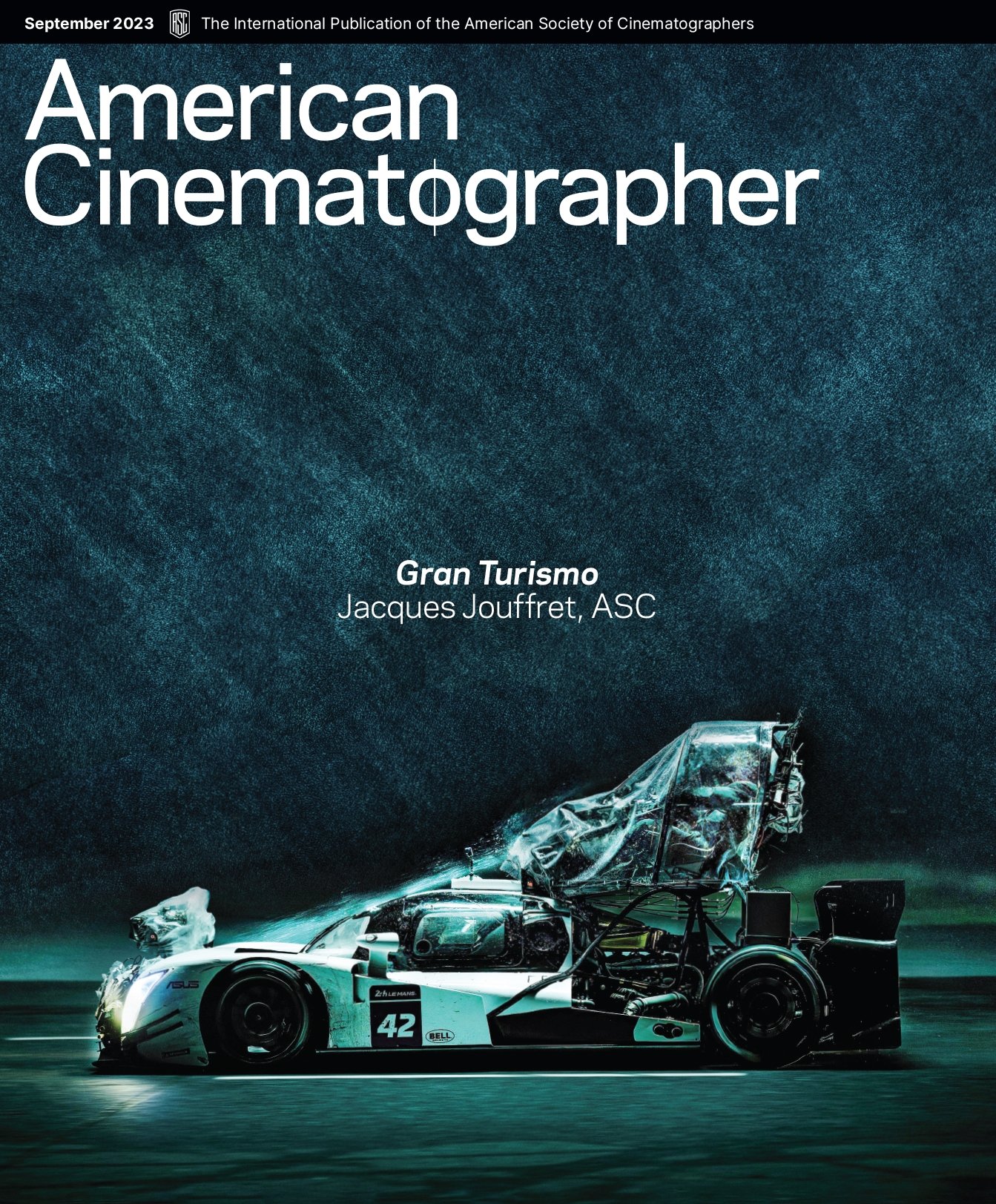

In the Driver’s Seat for Gran Turismo

Jacques Jouffret, ASC and director Neill Blomkamp capture high-speed, high-stakes racing action for this true-life tale of triumph.

Unit photography by Gordon Timpen

All images courtesy of Sony Pictures

Achieving cinematic realism — including the capture of real car racing — in the high-octane wish-fulfillment story of Gran Turismo was paramount for cinematographer Jacques Jouffret, ASC and director Neill Blomkamp. “It’s about a young man trying to make his way and all the anxiety that goes with that,” Jouffret says. “From the get-go, Neill wanted absolute reality. This was a true story. He didn’t want any fakeness, embellishing or making anything beautified. That was interesting to me because Neill is well known for his expertise in visual effects.”

Gran Turismo tells the incredible true story of Jann Mardenborough — son of a former soccer player in Cardiff, Wales — who, at age 19, won a spot on Nissan’s GT Academy television program. Tapping skills he acquired playing the Gran Turismo racing simulator game on PlayStation, he qualified to drive 500-horsepower race cars in real motorsports tournaments. He went on to become a finalist at the legendarily challenging 24 Hours of Le Mans in 2013.

A Live Sandbox

Working for the first time with Jouffret, Blomkamp took a similar creative tack as he had with the science-fiction thrillers District 9 (AC Sept. ’09), Elysium (AC Sept. ’13) and Chappie (AC April ’15), all shot by Trent Opaloch. “I like an ultra-real, very handheld, relatively honest way of shooting,” Blomkamp says. “That goes back to District 9, or even my short films. I like to oscillate between shooting handheld vérité style that can be very screwed-up and low-resolution, with actors going to complete darkness or overexposed, and then going to the other end of the spectrum with precise dolly work.”

On Gran Turismo, the director adds, he “wanted to create a live sandbox for the actors, unencumbered by lights. I wanted to be able to go wherever they went, to make it more documentary [style]. And I wanted multiple cameras. That’s pretty much exactly what happened.”

“It was like shooting a play. We could not ‘stop and go’ the cars. That’s why I fought to have 15 cameras — we only had one chance to pick up as much material as possible.”

FPV Strategy

Working largely on location in Budapest, Hungary, the filmmakers embraced the first-person-view (FPV) drone photography popular in coverage of extreme sports events. “I fly drones and single-rotor [radio-controlled] helicopters,” Blomkamp says, “so I’m really into drones as a concept. I’d seen so much FPV drone work in the sporting arena, and some filmmakers, like Michael Bay, have been using drones in [mainstream] film. I felt Gran Turismo would be interesting as a sports film that used what we’ve been seeing in sporting events portrayed cinematically.”

Real Cars at Speed

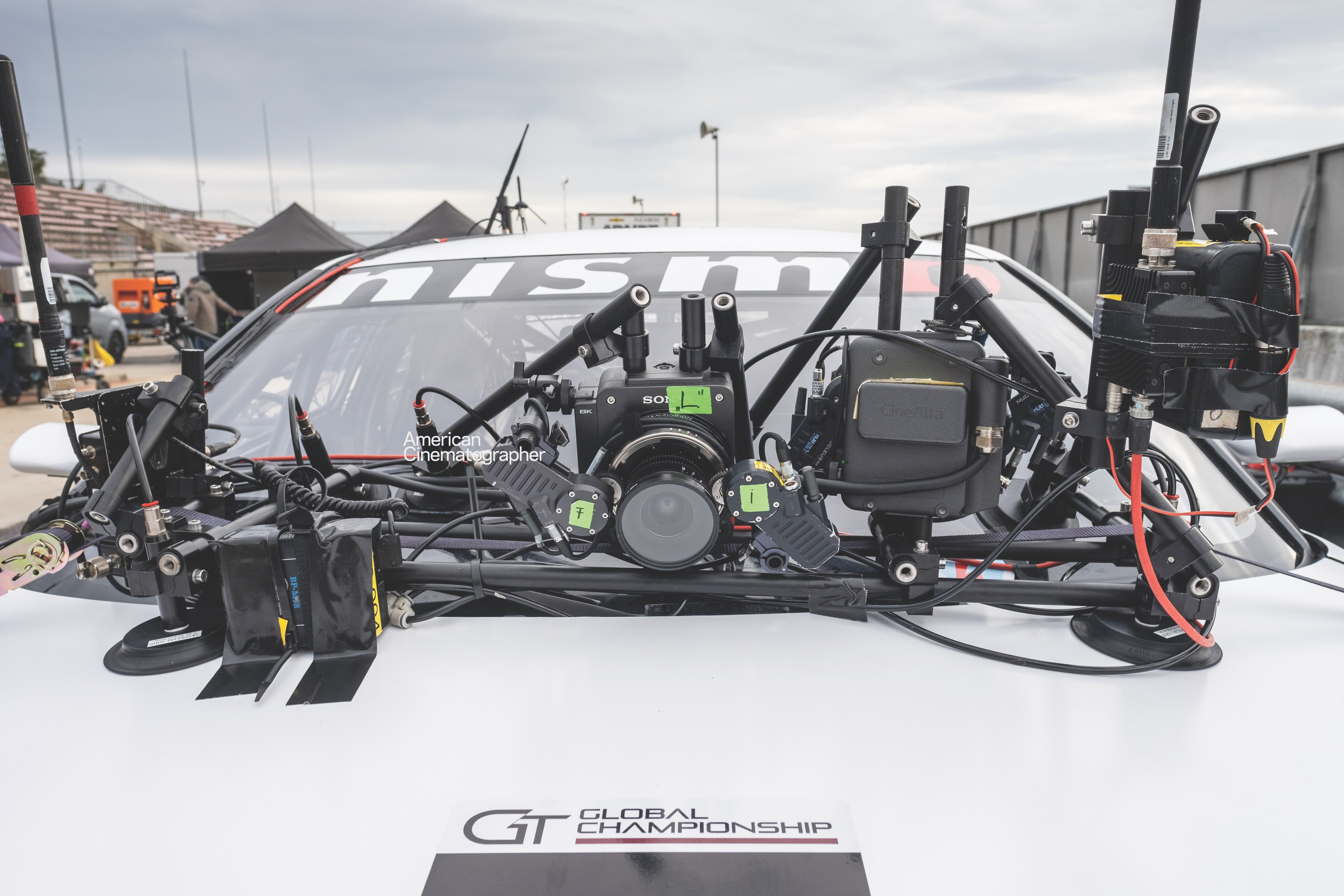

For in-car action, Blomkamp was determined to shoot performers in real race cars — at speed — without greenscreen or process shots. Key contributors to this approach included stunt coordinator Steve Kelso and racing consultant David Perel, a former sim-racing driver and GT champion, both of whom contributed to the choreography for a team of 26 stunt drivers. Mardenborough himself assisted in the choreography as well, in addition to offering personal insights — and performing as lead-actor Archie Madekwe’s stunt driver. Picture-car coordinator Dennis McCarthy provided racing vehicles and worked alongside special-effects supervisor Elia Popov at J.E.M. F/X Inc. in Los Angeles to customize a fleet of working GT3s. Race cars fell into three categories: hero picture cars, stunt versions and “pod cars” — the latter of which reroute driving, braking and steering mechanisms to driver-cages atop the cars, allowing stunt drivers to control vehicles. Stunt drivers could then achieve high velocities on the track while natural environmental lighting and g-forces affected performers in claustrophobic GT3 cockpit interiors.

“These were the actors in the cockpit,” Jouffret notes. “That meant we had to place the actor in the car, with a pod on that car, and I had to shoot into those very small car cockpits.

Tight Quarters

Jouffret drew on his recent experience shooting the fourth season of Tom Clancy’s Jack Ryan using the Sony Venice with the Rialto extension. The approach was similar to how Claudio Miranda, ASC, ACC captured cockpit action on Top Gun: Maverick (AC May ’22). “I had worked with Claudio, so I called him and Dan Ming, his first AC,” Jouffret says. “I somewhat followed their path. It made perfect sense. Claudio had cameras in F-16 fighter aircraft, while I was in race cars. They were similar in that [neither of us] had control — when a car starts racing and when a jet takes off, you have very limited time to play with. I also needed to have as many cameras as possible to catch what was happening.”

To capture driver performances, the camera team installed three Venice 2 Rialtos in each pod-car cockpit. Key grip Lech Gunovic oversaw rigs and bracketry, working with Hungarian crewmember Bence Czeh, and secured recording components in custom fan-cooled housings fastened to the exterior of the vehicle. These components were then tethered by cable to cockpit cameras arrayed around the driver.

“I used [Leitz] M 0.8 and Leica Summilux-M still lenses with iris and focus gear. The lenses are small but full-frame and f/1.4, and I had screw-on filters,” Jouffret says. He adds that he chose these lenses because “they have a very small and light form factor. I like the way they give depth to skin tone, and their smooth roll-off focus. I [used] a Series 9 screw-on diopter to bring the close focus to the actors’ face. The concept was that [the drivers] are in their own universe once inside the cockpit — it’s the only reality that matters.

“The cockpit cameras were locked off and facing the driver — one was neutral, one a little bit to the right and another a little bit to the left,” he continues. “Neill wanted to be sure not to confuse the audience; therefore, if there was a camera on the right side of the track and we cut inside, we stayed on the right side of the line, and vice versa.”

Exterior Angles

Additionally, the grip team fitted Red Komodo and V-Raptor cameras to vehicle exteriors. Venice 2 cameras (not using the Rialto system) were pressed into service as well — with one on a Talon head mounted to a Nissan Nismo GT-R tracking vehicle. For high aerial views, the production mounted a V-Raptor on a traditional non-FPV heavy-lift drone. Nimble FPV drones then swooped in and circled around cars to capture race action at high speeds.

Drone pilots from Dedicam and Lightcraft drone production companies operated FPVs in four quadrants around the track. To eliminate transmission conflicts with main picture vehicles, drone teams removed transmitters from the FPVs and used just the drones’ VR headsets to follow Blomkamp’s directions, producing footage that the director later reviewed as digital dailies. “Sometimes, I had a specific request to divebomb the car here and then fly over the trees,” Blomkamp recalls. “Other times I’d say, ‘Just do crazy s---, use the environment, do something cool.’ And then they would do that.”

To connect main-unit cameras to monitors on race locations, camera operator Onofrio Nino Pansini installed fiber optics and military-grade transmitters around the tracks, further developing a system he had built and used on F9: The Fast Saga. The fiber optics transmitted video signals just upward of half a mile from video village, which was situated at a given track’s pit-stop area. DITs were most often stationed at these spots, from which Blomkamp and Jouffret remotely tweaked exposure and focus as range permitted. “We had to wait for cars to go back around the track to pass the pit box,” explains Jouffret. “As they drove by, we had a moment where, very quickly, we could make adjustments. I only had control of focus and iris in front of the pits for a moment, but I would have picture all the time.”

“Like Shooting a Play”

Tracks were pre-lit with Arri SkyPanels and Creamsource Vortex8s. For vehicle interiors, “We typically would rig two or three Astera HydraPanels inside the cars,” Jouffret says. The cinematographer opted to avoid rigging any lights on the car exteriors, both for safety reasons and because “the round windscreen on the LMP2 [race cars] would make it impossible to hide reflections. So, we strove to keep a naturalistic approach and augment [the light] from inside the cars as necessary.

The cars were ‘violent’ but also very fragile, and they needed maintenance all the time. Plus, we had to [portray] constant communication between Jann in the car and his engineer [played by David Harbour], and all the drama going — from the pit boss to the pit perch — and cars coming in to refuel. I had cameras everywhere.” He further describes these elements of the shoot as “almost cinema verité.”

Previs was used for scenes requiring the integration of stunt driving, special effects, and visual effects. Visual effects supervisor Viktor Müller and three facilities, including VFX studio UPP, then created environment extensions and digital effects to complement the racetrack action. Digital effects included adding exploding crash debris, eliminating stunt-driver pods, erasing drones and removing camera rigs from exteriors of vehicles.

A Gamer’s POV

An early scene — with Budapest doubling for suburban Cardiff — established a key visual as Mardenborough uses his driving skills to outwit local police officers. The filmmakers used drones to capture down-views of Mardenborough’s car, and also created gamer-like perspectives of his car with the camera locked in position and capturing a high-angle rearview of the vehicle. For the latter, a Rialto camera rode on an 8' boom that extended from plates welded beneath the picture car. VFX eliminated rigging and stabilized car-to-camera lock-offs. This same angle was later applied to racetrack action, emulating Mardenborough’s “gamer vision” of his racing experience.

When asked how the crew worked to prevent potential vibration issues with the boom-mounted camera, Jouffret remarks, “To our surprise, [there was] little to no vibration at all. [The rig was] very solid because of the plate welded to the bottom of the car.” Gameplay cues reinforced the “sim driver” point of view. In a recurring motif, VFX mapped animated, glowing lines to racetracks, defining optimal driver lines that Mardenborough visualizes ahead of his vehicle. VFX artists also added animated graphics that signal lap counts and identity tags tracked to cars in races.

“I wanted to bring a little bit of the ‘virtual’ side of Gran Turismo into reality,” notes Blomkamp. “Jann was superimposing how he sees the world through the lens of [the game]. For example, early on, when Jann is in his bedroom modifying parts for his car, instead of portraying that [as] a two-dimensional [image], we extrapolate into 3D as his mind sees the intricacies of the car.”

Jouffret added to the protagonist’s first-person-perspective experience during certain dramatic moments when Mardenborough dons his racing helmet, using a helmet-mounted Red Komodo with a Panavision Petzval lens designed by ASC associate Dan Sasaki. This created optical distortions as the young man first enters the GT Academy racetrack. He adds that the Petzval lens “is sharp at the center and soft on the edges, somewhat dreamy,” helping to depict the protagonist’s “intense concentration and complete tunnel vision. I wanted to be right with him. He’s completely in this environment, in this space. Nothing else matters but the task at hand and winning at all costs.”

Grounded by Tragedy

Mardenborough’s dreams are shattered in two crashes — a near-fatal accident that claims a spectator’s life at Nürburgring in Germany, and a later incident at Le Mans. The surreal violence of the first accident, in which a strong wind upends his vehicle before catapulting it into the crowd, demanded an all-CG approach. “There was no other way to do it,” says Blomkamp. “We spoke to the special effects and stunt coordinators about trying to use cannons and wire pulls on a real car to try to get the car to do what happened. But it was never going to give us exactly what we needed.”

Instead, the production initiated the crash on location at the Nürburgring North Loop. At the corner where the accident occurred, Jouffret shot plates and passing cars. VFX then developed CG animation of Mardenborough’s perspective as his vehicle flips and hurtles off the track.

For the Le Mans crash, featuring an Aston Martin Vantage GTE slamming into a side barrier at Tertre Rouge corner, Hungarian special-effects supervisor Gábor Kiszelly staged the aftermath of a burning vehicle on the Hungaroring. VFX added the environment and race action. “Not only is the impact digital, [but] the whole lead-up to the impact is digital,” says Blomkamp. “We have three or four or five shots that were 100 percent CG in that sequence.”

Visual Punctuation

To punctuate the violence of the races, the editing team added staccato cuts of pumping pistons, spinning cams and shifting gears. The production captured engine interiors by physically cutting into a car, elevating the vehicle and using an external motor to drive the rear axle, which propelled the engine. A Laowa 24mm f/14 2x Macro Probe snorkel lens captured moving engine parts with minimal VFX assistance.

“There’s a moment on the Red Bull track where the Ferrari engine ignites,” says Blomkamp. “That was [footage of] a real engine plate with a real spark-ignition plate — comped together. Otherwise, that’s all real.” Realism informed all aspects of the team’s approach. “It was our goal to stick to shooting as much for real — until we could not,” says Blomkamp. “But technology now allows us to go further in [the real world] than we’ve been able to before. The main example of that is drone technology. The combination of scaled-down cameras that hold Imax-approved 6K sensors, and drones being powerful enough, small enough and with FPV relays back to the pilot — that’s opening us up to interesting filmmaking.”

Re-Creating Storied Tracks

An international project that included filming in Germany, Austria, Japan, Dubai and Slovakia, the production of Gran Turismo selected Budapest as its base of operations. The location offered a unique resource in the Hungaroring racetrack, a nearly 3-mile motorsports arena that was undergoing maintenance.

“That was a godsend,” says director Neill Blomkamp. “We had access to this Formula One track half an hour outside of Budapest. Because they were doing work on the track, they had cleared their schedule. That was unheard of. We treated the Hungaroring like a backlot. It was insane.”

Production designer Martin Whist redressed sections of Hungaroring to represent three racing venues, including the 2011 GT Academy at U.K.’s Silverstone Circuit, and the pit stop of Circuit de la Sarthe at Le Mans, which VFX facility UPP then enhanced with digital set extensions.

“We built different pits that each venue required,” Blomkamp explains. “We built the lower level of Le Mans as a set on the Hungaroring, and then the rest of Le Mans above the set was computer graphics.”

Of the film’s international racetrack locations, Le Mans was the only racing venue unavailable to the production. Instead, location teams staged the climactic race from a composite of three sites: Red Bull Ring in Austria, Automotodróm Slovakia Ring, and an abandoned airfield in Budapest that represented Le Mans’ Mulsanne Straight.

For night exteriors on Mulsanne Straight — a 3.7-mile straightaway made all the more nightmarish in rain — the production needed a way to simulate ambient light. Visual effects supervisor Viktor Müller and his team then enhanced the environment.

”Since we were going to re-create it, I had to lift the ambiance to give Viktor an exposure with details in the blacks,” says Jacques Jouffret, ASC. Twelve large construction cranes overhung the track, supporting 20'x30' softboxes, which the cinematographer used to model lighting depending on the direction of the race cars. “Each box had 28 Creamsource Vortex8 lights — 650 watts each. We wanted to make sure we had maximum color control and weather protection; the Vortex has an IP65 rating.” Reflecting on the artistic license taken by the production here, Jouffret notes, “Mulsanne Straight at night is, in reality, pitch black. The only lights are the headlights of the cars in front of or behind you.”

— Joe Fordham