A Goblin World Created for Labyrinth

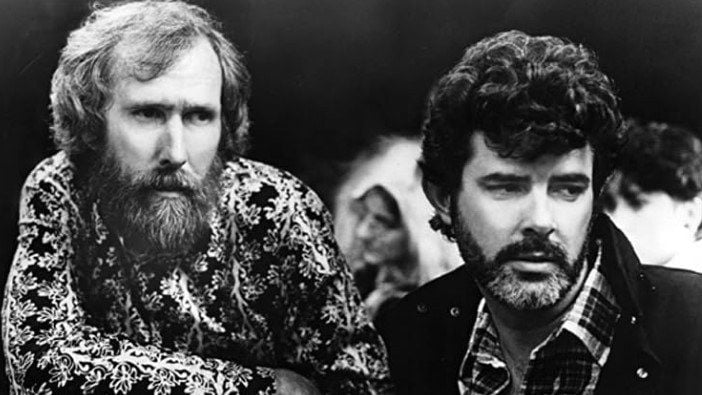

Forty years ago, Jim Henson spoke with AC about the making of his now-iconic fantasy classic Labyrinth.

This in-depth look at the making of Labyrinth first appeared in American Cinematographer's August 1986 issue. For full access to our archive, which includes more than 105 years of essential motion-picture production coverage, become a subscriber today.

A vast maze rises up against a painted summer blue sky, luring a young girl deeper into its heart, towards the seductive palace of the Goblin King. Her way is fraught with unexpected perils and pleasures, but as she encounters the terrors of this strange new world, she is aided and befriended by a wise old wizard, a gigantic but lovable monster named Ludo, and a spry old dwarf called Hoggle. You won't find this mythical land on any map, but in the fertile imaginations of Jim Henson and Brian Froud, two magicians who once before combined their artistry to create the fantasy universe of The Dark Crystal.

Henson maintains that Labyrinth, resembles The Dark Crystal only in its attention to detail and fantastic characters and situations — but its tone is much lighter. "With Labyrinth, we started off to do a much smaller film, we started off to do a more intimate thing about the relationships between these characters, and also, we intended it to be lighter weight because of Terry Jones' (of Monty Python fame) screenplay. One of the best things about Labyrinth is it enabled us to do something like the muppets and slightly like The Dark Crystal — a nice middle ground." While The Dark Crystal depicted a world completely divorced from our own, Henson has wisely chosen to incorporate two human characters into Labyrinth.

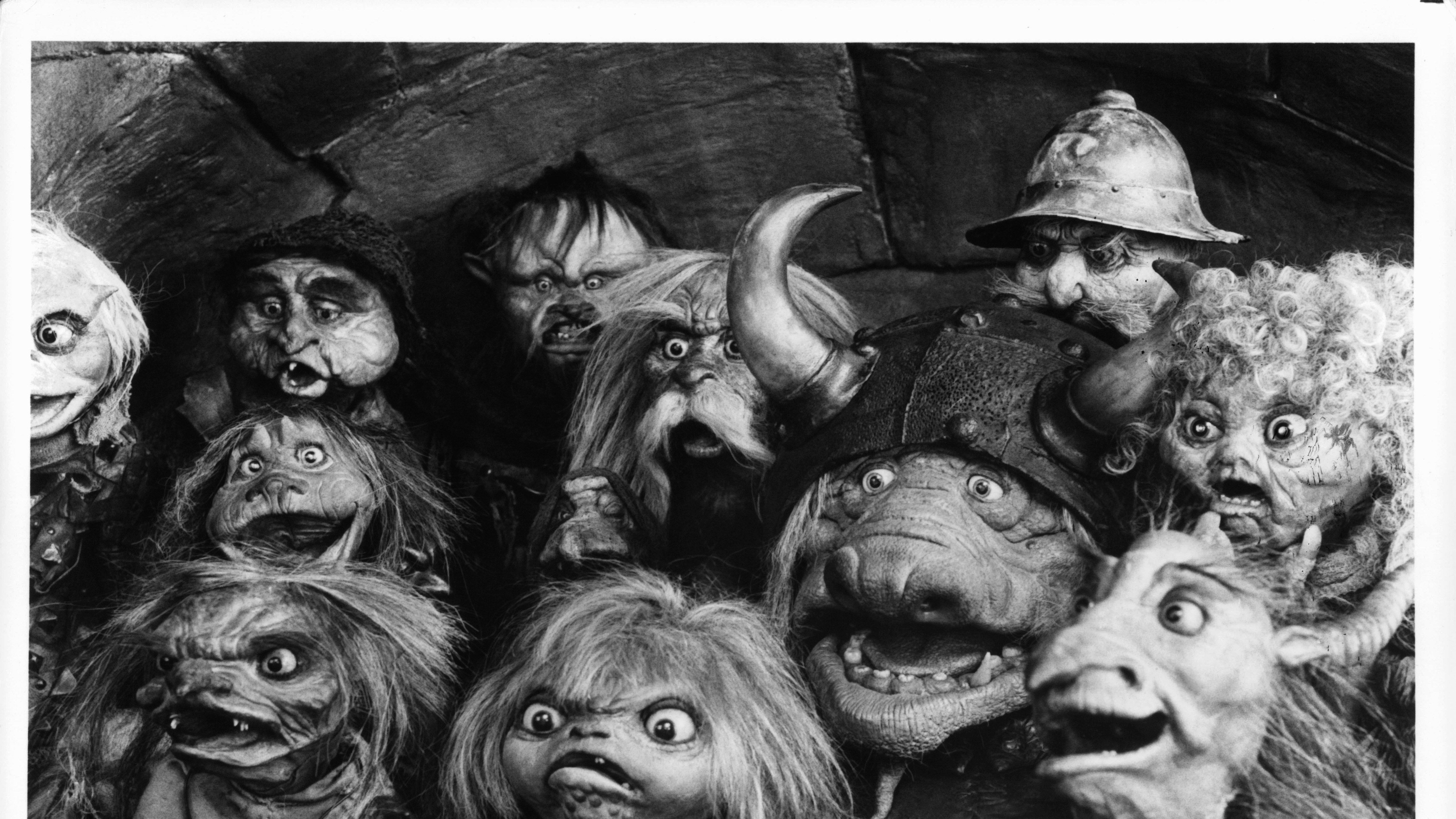

Fantasy artist Brian Froud, whose beautifully illustrated volumes, Gnomes and Faeries, became an international publishing phenomenon, was not only responsible for designing the film's muppet characters, he also developed the original concept for the film. "It started with an idea of Brian's about a journey through a labyrinth," Henson remarks, "and then we went through a lot of different configurations of the story before we ended up with this one. Since The Dark Crystal, Brian did a little pop-up book of goblins, a delightful little book, and I wanted to get the feeling, the wit and the whimsey of these goblins into the film."

"We wanted to do something different from The Dark Crystal and create another world,” Froud concurs. "We came up with the idea of goblins and a labyrinth, which we thought was a very interesting area to draw from. It's got a much lighter quality than The Dark Crystal and it's a lot more fun. I designed a general feel for the film, although production designer Elliot Scott specifically designed the sets. I went for a different color range. Whereas The Dark Crystal was very dark and took place in more of a twilight area, we felt we wanted more sunshine, so I went for much lighter colors and much brighter colors, with more reds in it. The lights are lighter and the darks are darker, so we’ve got quite a lot of contrast in the film as well, and there's more variety.”

Normally, Froud's work is highly organic and realistic in tone, but Henson's insistence on lightness in every aspect of the production led Froud to experiment with a cross between his own style and that of the Muppets. "I'm a great fan of the Muppets and I always have been," Froud explains, "and occasionally I designed things that I felt were an homage to the Muppets. Also, there are certain things that Muppets do really well, and it's always wise to capitalize on your strengths.

While a character like the wise man who wears a hat with a bird's nest in it definitely recalls Henson's Muppets, the giant friendly monster, Ludo, fits right in with the body of Froud's work. "We decided we wanted a nice big creature," he recalls, "and we thought it might be a challenge to come up with a fresh new side. Since the Muppets have been used to create so many monsters, we decided to reinvent it, and hopefully, that's what we did. Ludo was a problem to build. It took a long time to make something that large fluid and believable. We certainly pushed the technical techniques further than has ever been done before in terms of making it believable."

One interesting aspect of working in films that is not usually present in Froud's artwork is the element of collaboration. "In a way, you have to submerge your ego, though ego's very important," Froud realizes. "It's a happy collaborative effort and I really enjoy working with all the different crafts people. The importance they bring to the project because of all their various skills you must allow to come through. You can't say, 'No, my way is the only way,' you have to allow their input. On The Dark Crystal, I developed small models to show what I wanted to do, but I don't need to do very much of that now. People work directly from my sketches, and I supervise every step along the way. Certain aspects of my designs work and others don't, and so the characters have to be redesigned and rebuilt, and I often change features or some part of them to overcome the technical problems. That's why I usually like to do my designs fairly loose and broad, so that as they're being developed in the workshop, they can be made to work properly. Once we've decided which ones we're going to build, it takes a long time to build them and there's a lot of sculpting. The sculpture is very important in terms of capturing the character, and so with the sculptors' help, we bring it into perspective. I'm always after the spirit of the character."

The complicated mechanism designed to operate the facial features of the dwarf character, Hoggle, was compact and versatile. "There are about 18 radio-controlled motors inside of his face," Henson marvels. "Originally, I had thought that we'd have one radio-controlled head and a more elaborate cable-controlled head for close-ups, but we found we were able to get the full movement with the radio-controlled one. In the past, things that complicated were virtually always cable-controlled, but we decided to radio-control it, which gave us a lot more freedom with the character, because now he can walk about the set while we're shooting."

The actress who portrays Hoggle in the film is "small person” Shari Weiser, whose petite proportions caused some problems when it came to manipulating the character's oversized hands. "We wanted Hoggle to have sort of large, masculine, clunky hands," Henson explains, "with mechanical fingers. Shari has very tiny hands which fit about inside the palm of this character's hands, and when she moved her fingers, Hoggle's fingers moved, which took a while to refine. Once we got that working fine, of course, she had no power or strength in these mechanical fingers, so she coudn't pick up anything, and therefore, every time she actually had to hold something, we had to use another hand in a fixed position to hold the object."

Hoggle created other technical difficulties, mainly stemming from its built in video vision system, a refinement Henson had first employed on his Fraggle Rock television program. The vision system consists of a television monitor inside the costume and a camera which films the character's precise point of view, so that the performer inside is seeing exactly what the character would be. "We found when we first started to shoot with Hoggle that the whole video vision was not good, it didn't work well for her at all. It took us a little while to discover that, but she ended up looking through the mouth of the character instead." Oddly enough, the video system inside the gigantic Ludo costume, which employed two video monitors, one showing the character's point of view and the other featuring the actual shot, worked absolutely perfectly for the performer.

Despite the literal tons of extra equipment necessary to bring a film like Labyrinth to the screen, Henson does not view the technology as an end unto itself, but as a tool. "All of the technical stuff we do I think of basically as designed to get a better performance," Henson comments, "even when we have all of that radio controlled stuff, all it is really meant to do is to take a puppeteer's single performance and amplify it to make that performance more dimensional. It's always performance! You've got to start with a very talented performer in the first place, and all of the rest of that stuff is just icing and gravy - though not at the same time," Henson laughs.

It is because the performances of the Muppets are so critical to the success of his films that Henson employs a virtual arsenal of video cameras and monitors. "Working to a monitor is absolutely essential to our performance," Henson insists, "and we have virtually no performance without that monitor. We've always done that because of the way we manipulate the Muppets. At all times, with all of our films, we've used a through-the-lens video system. Replaying the tape is not as important as being able to watch it while you're shooting, although we use the video a great deal throughout for all kinds of things. We use it the way other people would use continuity notes. We match to the previous shot because you can see all kinds of things. There's no argument about which hand was holding a pencil, and you can match the speed of movement from one shot to another. You can try things to see if they'll cut together such as from a wide shot to a closer shot, as is often the question. There were times when we'd have as many as several dozen monitors around the set, and occasionally we'd use a separate video camera just to get an extreme close-up of a character whose face we wanted to watch specifically for eye focus or lip movement, because all of that is critical. We're always watching for performance."

Directing a film of the scope and complexity of Labyrinth would have been an even greater task for Henson had it not been for the assistance of his son, Brian Henson, who took a great responsibility off his father's shoulders by coordinating and supervising the puppeteers. Additionally, to his father's surprise, Brian supplied the voice of Hoggle! ''As we were working, Brian's voice developed and really captured the character very well. I like to work with the performer doing a voice at the time of the shoot because then you get a performance that relates to the voice, although most of the time we change it afterwards. We kept Hoggle's voice, although when I started I was certainly under the assumption that I would change it. In the final soundtrack, we took the voice and ran it through a harmonizer and dropped it down a bit in pitch, which gave it a quality that I think looked more like the size of the character. Brian was just terrific on this, and it was so much fun for me. He not only did Hoggle, he was also running that team effort as overall puppet performance captain, supervising the placement of people and the assigning of parts. There's quite a bit of work involved in getting people into place and also in running a performance workshop beforehand. It's so useful not to have the director do all of those things, because there's a full time job just getting the rest of that together," Henson explains.

The film's numerous stage-bound settings created their own unique problems. One of the trickiest of these locations was a large swamp filled with bubbling paint, known as the Bog of Stench. "It's the Bog of Eternal Stench," Henson corrects, "and if you step in this thing, you smell bad for the rest of your life! It also makes terrible, bathroom-y noises, and try to imagine the worst possible smells! George Gibbs of special effects designed our Bog for us, because it had to have special effects taking place in it. For a scene where Ludo calls the rocks and great boulders come to the surface of the water so they're able to walk across the bog, we had to be able to get the big rocks all the way down in there, which meant the bog had to be five or six feet deep. The Bog had paint in it which would periodically get splattered on our shirts, and it wouldn't come out. We had a character named Didymous, who rides a trained dog across the rocks - a complicated thing - because if the dog slipped in, and the stuff was slightly slippery, we would have had a sort of green-brown uncleanable dog! So he had to be on a safety wire, and so did Ludo. We actually built a set of pants for the dog, so he wore little booties and fur pant legs, because we figured we could catch him if he did slip in, but he probably would have gone in as far as half a foot."

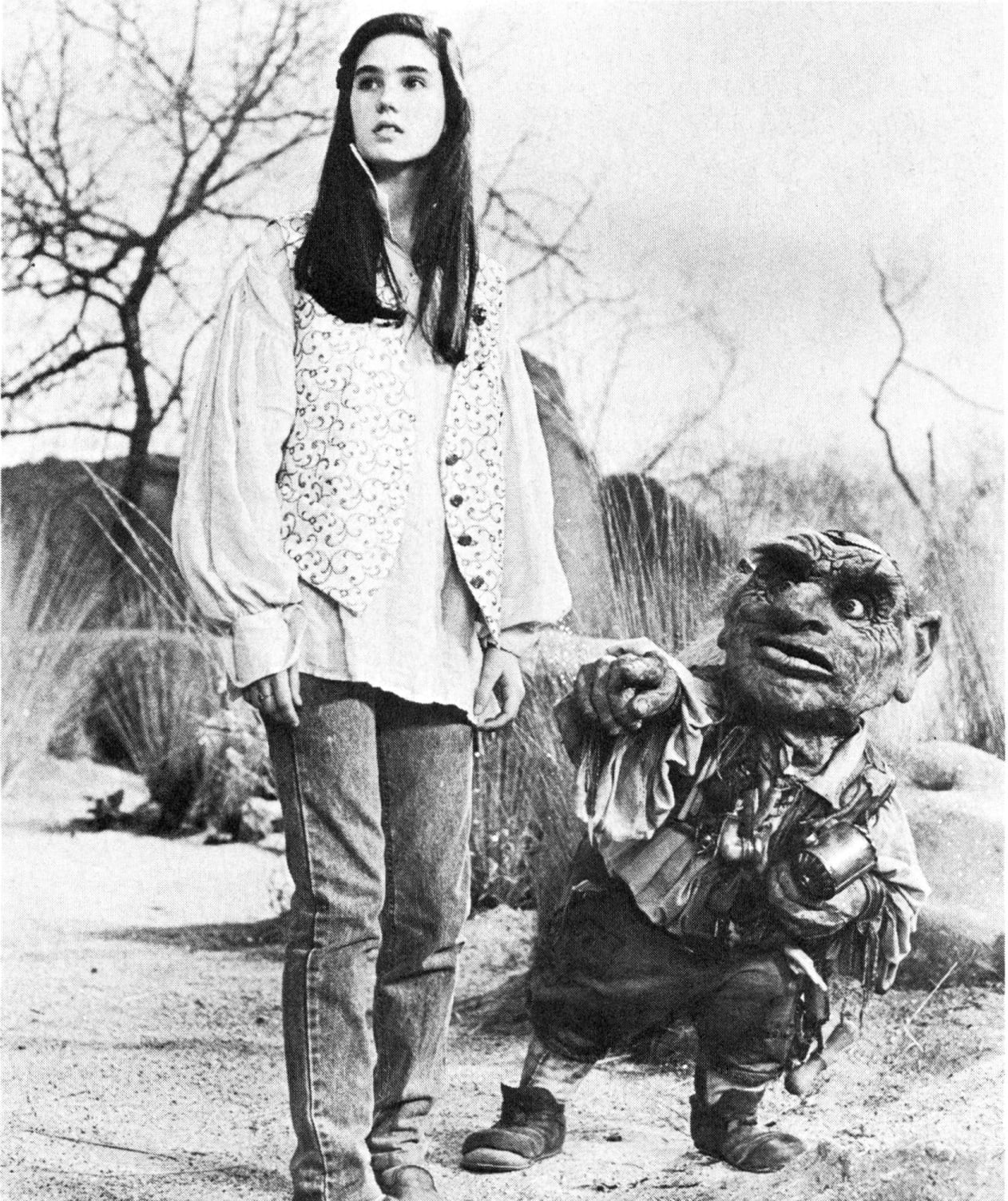

There was a large staged fall in the film as well, as actress Jennifer Connelly, who plays the adolescent protagonist, Sarah, is swallowed up by The Shaft of Hands. The set was built by George Gibbs, and the main problem seemed to be getting enough hands in there to make it look right. "We wanted to have the idea of Sarah falling through this shaft with all these hands reaching out for her,” Henson says. "We had about seventy-five extras in there, a dozen or so of our own performers, and then another several hundred more stuffed rubber hands. We got everybody in and I looked at it and I said, 'George, there seems to be a couple hundred hands missing!' and he went slightly white but he had them for me a few days later. It was an elaborate rig, because Jennifer was in a body harness on a pole arm that went out straight behind her body, and then the camera would track right down opposite her. We shot it at London's EMI studios on the Star Wars stage, which is quite tall. Jenny was up at the top of the set in this harness, quite an uncomfortable thing. There was nothing underneath her, which is scary as hell, but she was such a trooper! If anything, she slightly enjoyed heights and she never complained. When we cast the part of Sarah, I had no idea how many high-altitude shots there would be and things where she needed to do near stunts until we got into it, and what I found is that Jennifer loved all the challenges and really did it well."

Another set the Labyrinth crew built up on the Star Wars stage was a goblin village designed by Elliot Scott, which featured some unusual built-in tricks to make it appear larger than it really was. "Scotty did some really daring things with false perspective," Henson recalls, "and the goblin village was built up with smaller houses at the end of the streets, and even in the mazes themselves, he would often use false perspective to extend the ends. The goblin town itself had to be one of the prettiest sets I've ever worked on. Scotty designed all of these wonderful little goblin houses that looked vaguely like a fairytale gone bad. They were just wonderfully old, sort of asymmetrical and vaguely medieval looking houses, and we shot them every which way. Scotty is such a good designer and he knows his craft so well, it was so much fun.”

Henson has longed to create an M.C. Escher-inspired sequence ever since he first began making movies, but the logistics of transferring Escher to the screen made Henson reconsider the approach to the material. "It's funny,” Henson says, "I've admired Escher's work for years and I've always wanted to try to accomplish that on film, but in many ways, we didn't do it as much as we could have. It would've been interesting to try to throw everything every which way, but we don't particularly. I kept Sarah upright all the time, because if I decided to throw gravity off completely so she could then roam upside down and around the walls, my feeling was, what's going to be ground-zero for the audience? So I decided to keep her upright and I think that works because it's vaguely what the audience's perspective would be.”

Henson's scheme works, and the sequence inside the goblin king's castle should go down as a landmark in fantasy film history. The logistics of the scene were quite complex, and Henson debated at one point whether or not to use mirrors to achieve the desired effect. "We considered that and actually, I think we had a mirror installed on the floor of the set, which we didn't use,” Henson says. "We built a large set which was basically a box open on one side that we could shoot from all kinds of angles. There were a lot of different views we could get out of that one set, and when we turned the camera on its side, we ended up with many more possible views. We had art directors Michael White and Terry Ackland-Snow involved in working out some of the problems of using split mattes. It really was an art director's problem to try to figure out that if you want David to be walking upside down beneath where Jenny is standing, what you need to shoot as your matte. Sometimes we just put the camera on its side or upside down, and there were two effects using a stuntman doubling for David in a rig, where he's able to make a complete swing from upside down to right side up. It’s all fairly simple stuff and yet, when you cut it together, it's something effective."

Another simple but effective bit of trickery associated with the David Bowie character involved his seeming ability to manipulate several crystal balls at once. "I try to do as many of the film's effects as possible for real, in front of the camera," Henson explains. "There is a juggler I've known for years named Michael Moschun and he does a whole act with crystal balls, and as we put this film together, it just occurred to me that we needed David to manipulate this crystal ball, so I found a bunch of different ways to use Michael. We did things like placing his arm in the sleeve of David's costume while he’s crouching down behind his back, and so that hand was not David's hand. Michael is really incredible, and he'd be looking the other way with his eyes closed so that he could just feel what the crystal ball was doing! We also did a couple of shots where we put Michael in David's wig and shot over his shoulder so he could use both hands. It ends up being pretty invisible.”

There are a number of equally invisible but impressive miniature effects in the film, most notably a large scale model of the labyrinth at dawn that fades seamlessly into a painted backdrop, and a scaled down version of Sarah's house for the film's final shot. "The film ends with a party going on in Sarah's bedroom," Henson relates, "and there's this final pullback shot from the party going on at the house right up to the moon. We filmed a shot of the party and put that on a 16mm projector in the window of Sarah's room, and then the camera follows an owl from its perch outside the window as it flies up towards camera and then into the moon. We shot the owl separately as a radio-controlled puppet and then matted that into the scene, which worked out nicely because of the moonlight."

Labyrinth's opening title sequence also involves an owl, created by computer animation courtesy of Digital Productions, the same people who provided the spaceship effects for The Last Starfighter. "They did a beautiful job building a white owl into the computer and animating it," Henson says. "It's a fascinating process. Every feather on the owl's wings is animated, some forty feathers, and the stylization of it is really quite beautiful. We have the owl flying past black mirrored walls, so you see the owl reflected in the mirrors as he flies along, and it's really quite elaborate.”

One of the more elaborate aspects of Labyrinth is its multileveled screenplay by Terry Jones, based on a story by Henson, which reflects a rather unusual bent in its director's taste: a desire to create a film of substance. "I like a film to be about something and to relate to life,” Henson elaborates. "This film is really about a young girl growing up, and how much of that shows up in the film almost doesn’t matter, though it's what we had in mind when we put it together. To me, it's vaguely about taking responsibility for your life, because a lot of kids, a lot of people, don’t take responsibility for their lives and they don't realize that they're the ones making their lives whatever they are. Sarah's favorite expression in the film is "It's not fair!”, which is merely saying that something else is to blame!”

For Henson and Brian Froud, the ordeal of Labyrinth has passed, and what remains is an entertaining and technically superior fantasy film. Despite the years of hard and sometimes frustrating work, the two wizards may soon collaborate again on a television project, while Froud is also developing an animated film.

Photos by John Brown and Nancy Moran.