Lord of the Realm: Peter Jackson Talks to AC

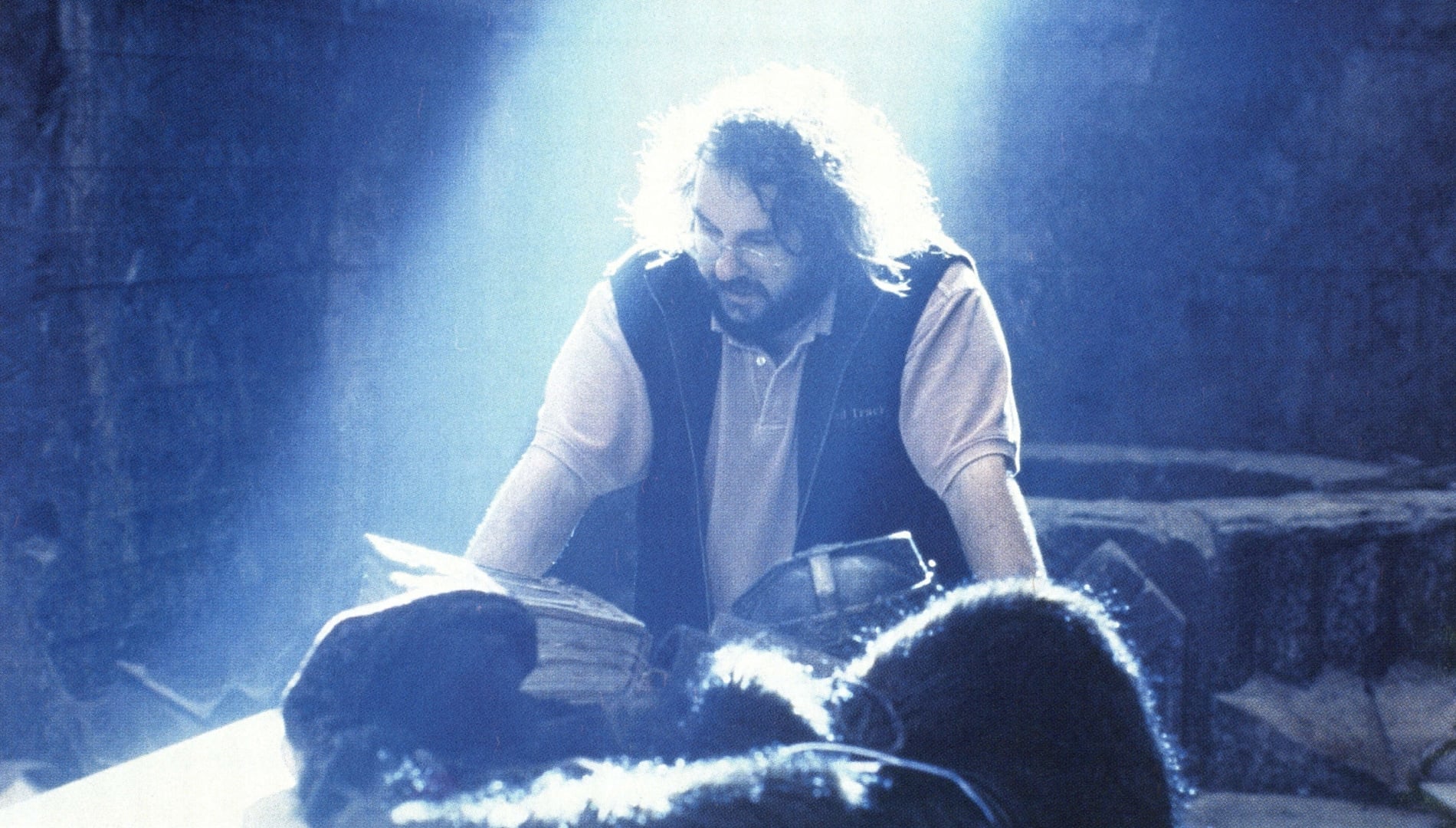

Director Peter Jackson takes on the daunting challenge of bringing J.R.R. Tolkien's Lord of the Rings trilogy to life on the big screen.

This interview on the making of The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring first appeared in American Cinematographer's December 2001 issue. For full access to our archive, which includes more than 105 years of essential motion-picture production coverage, become a subscriber today.

Within the film industry, there’s a tendency to compare Peter Jackson to George Lucas. Both began as experimental filmmakers, both have created entire worlds populated with outrageous characters, both launched their own effects houses, and both have even made nostalgic films set in the ’50s about their respective countries.

Of course, Jackson’s previous films aren’t what most people this side of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre would call family fare. His early works, such as Meet The Peebles and Brain Dead, dealt with disturbing, sometimes disgusting material, never fearing bad taste if there was a good laugh to be had. Then he made Heavenly Creatures, the tragic true story of a female friendship gone horribly awry, startling critics who had pigeon-holed him as New Zealand’s Sam Raimi. Jackson subsequently returned to macabre territory with The Frighteners, a supernatural comedy-thriller overflowing with ghosts, and he is now ready to unleash his own fantasy trilogy, beginning with Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring.

Finding a cinematographer to film the trilogy, whose installments were shot over 15 months of principal photography, was one of the initial hurdles Jackson faced. He eventually selected Andrew Lesnie, ACS, ACS, whose credits included the beloved farmyard fantasy Babe and its sequel, Babe: Pig in the City.

Despite his hectic schedule, Jackson took the time to speak to AC contributing editor Ron Magid about the many challenges involved in directing The Fellowship of the Ring.

American Cinematographer: What convinced you that Andrew Lesnie was the right cinematographer for the Rings trilogy?

Peter Jackson: I spent some time trying to decide who I’d like to use, and the irony is that Andrew was one of my very early choices. He was unavailable at first, so we met with several other cinematographers. We eventually heard through the grapevine that Andrew was available, which was a stroke of immense luck for us, and we flew him over to New Zealand. I love the photography Andrew did on the Babe films. I like the heightened feel, the saturation and the colors, and I love his use of natural light to create amazing bits of backlight, which I always find to be a very effective look. The Babe films also use a lot of wide-angle shots, which I tend to favor. I didn’t necessarily want the exact look of the Babe films for our movie, but I liked their stylization. We also looked at other examples of Andrew’s work. He’d shot a film in China called Temptation of a Monk [a.k.a. You Seng], and while it too was stylistically very different from what I was imagining, I saw some interesting things in it. I liked his use of natural light and his compositions. After watching these films, I felt that Andrew had a very good eye and I felt comfortable with his photographic sensibilities. I just wanted to make sure I chose the right person before I committed to 15 months of working with a cameraman with whom I’d never worked before.

Had anything you’d done previously prepared you for a 15-month shoot?

No. You normally shoot principal photography for 12 to 16 weeks, so Rings really became an endurance test. However, working that way did have its advantages. Our team had wonderful spirit because many of them had never previously committed to such a long-term project. Everybody was there not because it was just a gig, but because he or she had made a very carefully considered, conscious decision to be a part of it. It wasn’t a light decision for either the cast or the crew, because everyone had to relocate to New Zealand for a long period of time. Shooting this trilogy was really a case of taking one element at a time, doing what we needed to do, and then moving on to the next. From a psychological standpoint, none of us really focused or dwelt too much on the overall size of the project because it was a fairly daunting prospect. The collective sense of enthusiasm and excitement carried us through it very well.

You were well into preproduction before Lesnie joined you. How did he contribute to your vision for the trilogy?

We were prepping three films simultaneously, so we did have more work than usual done by the time we looked around for a cinematographer. After Andrew got involved, some of our plans changed a lot. I like being a collaborative person, and I regarded Andrew as my closest collaborator. I’d walk on set with an idea, but as soon as we began blocking the scene with the actors, we’d open things up and have them suggest ideas. Naturally, that process began to affect our original plans for the scene.

Meanwhile, I’d begin thinking of ways to shoot the performances, and about how I was going to cut things together to get the drama, and I’d start to lose my sense of how to compose the image! I relied very much upon Andrew to think of ways to frame shots, and he always found interesting things to put in the foreground to establish the image. I tend to favor wide lenses rather than long lenses, and I also relied on Andrew to keep that tendency in check; he occasionally suggested a slightly longer lens to make the scene more attractive or to make the actors look better. Andrew and I always tried to give the actors as much flexibility as we could.

Sometimes you had as many as nine units working simultaneously. How did you manage that?

The reality was that I couldn’t direct everything. It was a practical consideration we just couldn’t escape — otherwise, we’d still be shooting the film! Making a film of this size is like running a war. It’s picking the right people and just making sure that those lines of communication are as clear as they can possibly be.

We had satellite feeds linked up to wherever the other units were — sometimes hundreds of miles away — and I’d be sitting on the set with a bank of TV screens in front of me that would usually show us what was happening with two of the other units. John Mahaffie and Geoff Murphy were directing the two principal second units, and most of the time I just kept an eye on what they were doing rather than trying to direct all three units at the same time. The trick for me was to simply let them direct, because the more I took away from them the more it took away from the job I was doing. John and Geoff would call me if they had a question, and I’d be totally aware of what they were talking about because it was on the screen in front of me. Some days it was tough, though.

How did you and Lesnie maintain visual continuity on the sequences you didn’t direct and shoot?

That involved a lot of meetings, and Andrew was involved in the lighting of every single scene, regardless of whether he was actually on a given set. He talked to the other cinematographers and looked at the dailies. On some days when we had four or five units shooting, we’d have five hours of stuff to watch when we finished shooting at the end of the day! Watching dailies was like watching Ben Hur or Gone With the Wind! If everyone was in town, then dailies were an opportunity for all of us to watch each other’s shots and talk about them. Ifthe cinematographers weren’t in town, Andrew would phone them, talk about what they’d done that day and discuss ideas for the following day. He always kept a finger on the pulse.

It’s been said that you never want the camera to sit still.

It’s based on a very simple principle of mine: the camera is another character in the scene. Just as an actor can express emotion, I strongly believe that moving the camera around enhances the emotion of a scene. The camera can also convey an attitude to the audience that is independent of the attitude coming from the characters, and sometimes it’s interesting to use that perspective to give the audience a point of view that the characters aren’t aware of themselves. Also, I believe that if you move the camera sensibly, it draws the audience into the film a bit more. They’re not just being asked to interpret a series of static shots all by themselves; the camera is doing some of the interpretation for them, which provides a more gentle, comfortable ride through the movie.

Did your highly mobile camera create problems in terms of the rigging on set?

Andrew was incredibly flexible, and I think he learned very quickly about what he was dealing with in working with me! Even though the storyboards or our discussion may have indicated the scene was going to be covered in a particular way, I think Andrew knew it was likely to change somehow on the day. That allowed him and his gaffer, Brian Mansgrove, to pre-rig and pre-light sets to allow for lots of flexibility. They could create lots of different looks within the same set.

Why did you shoot even simple dialogue scenes with multiple cameras?

I’ve never really used multiple cameras that much before. I’ve always imagined the coverage shot by shot, so this was really the first time I got my head around multiple cameras. We ultimately used them for speed, because if you can design a two-shot and a single within the same setup, you’ll usually get through your day’s work twice as fast. We had a lot to shoot, and using multiple cameras became a very good way to get through the day a bit faster.

What I came to enjoy about that approach is that even though the coverage of a particular scene might have indicated just one camera, I could look around for other possibilities where the second camera could be used. I began using the second camera to grab shots that I wouldn’t otherwise have even thought about getting. I could also film inserts of actor’s hands picking up a teacup or get tighter shots of their faces or eyes while the main footage was being shot.

Why did you shoot in the Super 35 format?

I like the 2:35:1 anamorphic frame; I enjoy its proportions. It becomes a choice of whether to shoot with Panavision anamorphic lenses or with Super 35 sphericals and squeeze the footage later. Heavenly Creatures and The Frighteners were both shot in Super 35 simply because the rental companies in New Zealand are primarily Arriflex-based and we didn’t have any Panavision gear at our disposal. In working that way, though, I came to like Super 35. I like not having to think about anamorphic lenses, and I like the little bit of extra headroom at the top and bottom of the frame, which enables you to be a bit more flexible when you do your video transfer. Even though Panavision equipment would have been available for Lord of the Rings, Andrew and I both felt we should stick with Super 35. Also, the visual effects that Weta artists have done on my films have all been done with Super 35 neg, so we felt it was probably wise to stick with something we knew.

What was the hardest set to work in photographically?

The toughest but ultimately the most satisfying set was Bag End, the home of Bilbo Baggins, because we were shooting different scales. We had major dialogue scenes between Gandalf and either Bilbo or Frodo, and in both of those situations Bilbo and Frodo had to appear to be 4 feet tall while Gandalf had to appear to be 6 feet. In order to accomplish that illusion, we used either bluescreen or a variety of complicated rigs. Some of the shots involved moving forced perspective on platforms that were slaved by computers [to the camera]; when the camera moved, the platform with the actor on it would move as well to stay in perspective.

We also built two different scale sets. In the first, a normal person would look like a Hobbit because the doors were a couple of sizes too big and the ceilings were a good height. In the second set, which was much smaller, Ian McKellen, who was playing Gandalf, was in danger of banging his head on the ceiling, and the doorways were all so small that he had to crouch to go through them. Unfortunately, once we had 20 or 30 crewmembers lugging gear around in this tiny set, many, many people banged their heads on the ceilings! We also got sore backs because we were always crouching in there for hours at a time. It was a bit like being inside a submarine, and the lights would heat the space up very, very quickly — it would become like a little sauna bath. But that set provided some of my favorite scenes. It was worth the effort.

Did you and Lesnie come up with a signature look for each location?

We did a color plan for the movie, and we were very careful with our design and our costumes. Ultimately, most of the film has been digitally graded to achieve certain moods and feelings with color. For instance, the early scenes in Bag End have a very comfortable yellow-orange glow from the roaring fireplace, a look that creates off a very cozy, at-home feeling. A little later, though, the Hobbits go to Bree, which is a very oppressive, sinister village that’s full of Men. The Hobbits feel very intim¬ idated there, so we gave our pub set a rough, rather frightening feeling by making the color of the fire a dirty, nasty greenish-yellow. So even though [both settings are] essentially lit by a fireplace, they have completely different moods and feelings. We wanted to give the scenes with the Elves a feeling of melancholy, because this wonderful race of people is now leaving Middle-Earth, never to return again. Rivendell therefore has very autumnal colors, as if the Elves are in the autumn of their years. However, we wanted our other Elven location, Lothlorien, to feel very different than Rivendell. We took our cue for the lighting of Lorien from Tolkien: the Elves worship the light from the stars, so we lit Lorien with very beautiful blues and clean white colors. Their lamps emit a pure white light instead of the orange light of normal oil¬ burning lamps, so Lothlorien has a very pure feeling.

The Moria Mines were a very difficult lighting challenge for Andrew, because the Fellowship is essentially walking through tunnels from one side of the mountain to the other for four days. There’s no natural light and it’s totally pitch black, but we obviously had to have some ambience in there. We wanted the lighting to feel realistic, as if there were no sources other than Gandalf’s staff, which occasionally lights the way. We decided on a very muted green tone that we thought would give Moria the feeling of a tomb — which it essentially is, because the Dwarven civilization there has long since been destroyed. We liked the way that the slightly green ambience actually sucked the warmth out of the actors’ flesh so that they began appearing very corpselike.

How did the digital timing help create distinct looks for each locale in Middle-Earth?

The wonderful advantage of digital grading, which we did with timer Peter Doyle and PostHouse AG, is that it can go beyond what film grading can do: you can adjust gamma and contrast, but you can also vignette and isolate pieces of a shot. It’s similar to film grading in terms of basic color manipulation, but you can also take a scene that was shot on a very dull, overcast day and increase the contrast, burn the highlights out, thicken the blacks and add warmth to the highlights without adding any warmth to the shadows. In short, you can subtly make a dull, overcast scene look as thought it was shot on a bright, sunny day. We could also isolate characters and apply a ProMist filter to the Elvish skin-tones so that they’d radiate a slight glow without affecting the rest of the shot. Digital grading allows you to apply a remarkable layer of creativity to the film after you’ve shot it.

Andrew and I didn’t want anything to feel artificial; we wanted to make the film feel like a ‘real fairy tale’ rather than real life as we know it. We wanted to give the trilogy a feeling of antiquity, a slightly fantastic feel, while also making it feel real.

Interview by Ron Magid. Edited by Stephen Pizzello. Unit photography by Pierre Vinet.