Imagining Middle-Earth for The Lord of the Rings

A top-notch team of visual-effects experts ventures into a fantastic realm on The Fellowship of the Ring.

This piece on the making of The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring first appeared in American Cinematographer's December 2001 issue. For full access to our archive, which includes more than 105 years of essential motion-picture production coverage, become a subscriber today.

Bringing J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings to the screen was almost as perilous a saga as Frodo’s journey into Mordor. New Zealand director Peter Jackson, whose oeuvre ranges from the disturbing drama Heavenly Creatures to the zombie comedy Dead Alive, says he began to contemplate the enormity of the task after New Line gave him the green light to make the trilogy. “We had developed the project as two movies for Miramax, but they put it into turnaround because they wanted to reduce it to a single film, and we didn’t,” explains Jackson. “So we met with Bob Shaye, [then-president] of New Line, who suggested that we should make three films since there were three books. Up to that point, we weren’t even thinking about what it would take to make these films; we were just desperate to save the project. Our sheer joy at realizing the project was going to survive, and that we’d get to do it, was the dominant feeling. It wasn’t until later that the reality of what we’d actually gotten ourselves into sunk in!”

Although visualizing Tolkien’s Middle-Earth was an incredibly daunting task, it had been an ongoing project for a variety of artists since the novels were first published. “The advantage with Tolkien is that his works have had a 40-year life, and a lot of people have designed things for calendars and book covers, including Tolkien himself,” Jackson says. “The first thing we did was to collect all of the artwork that existed. We were very taken with two artists in particular: Alan Lee, who’d made a beautiful set of 50 watercolor paintings for an edition of the trilogy about 10 years ago, and John Howe, who’d designed a lot of book covers. Both of those artists really inspired us, and we were writing the screenplay with their pictures spread out on the floor. They not only captured the flavor of the book, but they also drew things that went beyond what we could imagine ourselves.”

Jackson subsequently hired Howe and Lee to serve as conceptual artists on the project. As the design process began, Jackson decided that he wanted to avoid the “softness” associated with digital effects and instead create Middle-Earth for real. Going against the trend of combining 3D computer-generated environments with digital matte paintings, Jackson decided to build the world of his film photographically — using digital techniques to hide the seams — and to create characters that were beyond the technology of makeup or creature effects. “We wanted to create a feeling that we’d gone to Middle-Earth and were able to shoot on authentic locations,” he says. “We wanted the castles to appear as though they’d been designed by a particular culture to fit in the landscape. The mantra of our design work became ‘Make it real.’”

To accomplish his goal, Jackson asked his own effects company, Wētā Workshop (whose credits include Jackson’s The Frighteners), to oversee five key departments. Wētā co-founders Richard Taylor and Tania Rodger supervised the work. Says Taylor, “We chose to look after the design, the fabrication and the on-set operation of the special makeup effects and prosthetics, the armor, the weapons, the creatures and the miniatures because of our absolute belief that we needed to bring a singular Tolkienist brushstroke, a singular stamp of technique, style and design to the work. Over the first few years we produced literally thousands of drawings and 3D maquettes.

“There has been an overriding disbelief that a single workshop could look after so many departments,” he continues. “For the four years of production, I wore a radio telephone that had an earpiece and a mouthpiece. I could be talking to a group of people while other information was coming through the earpiece, and I could hold other meetings using the ‘yes’ and ‘no’ button on the RT. It really freed up communication and doubled the work capacity. Otherwise we would’ve had to scatter the departments around the world, which would have dissipated the singular visions of Tolkien, of Peter and of our collective design force here at the workshop. It was a scary thing to stand up for, but I’m glad we did it, because there is a strong, unifying aesthetic through all of the work.”

Meanwhile, New Line set up a production company, Three Foot Six (which is, incidentally, the height of a Hobbit) to oversee the complex production and postproduction of the trilogy. Under that banner, Jackson assembled an international team which included some of the greatest talents in visual effects. The participating Americans included Mark Stetson (The Fifth Element) and Jim Rygiel (102 Dalmatians) as visual-effects supervisors; Ellen Somers (What Dreams May Come) and Eileen Moran (Fight Club) as visual-effects producers; Randall William Cook (The Gate) as creature-animation supervisor; and Alex Funke (Total Recall), David Hardberger (Dinosaur), Chuck Schumann (Terminator 2) and Richard Bluck (The Frighteners) as visual-effects cinematographers. The team rapidly expanded to include about 200 other artists from America, New Zealand, England and Germany, and it came to include Hollywood effects powerhouse Digital Domain as well.

“[The New Zealand] film industry only goes back 20 or 25 years, so we just didn’t have the skills base we needed to tackle something of this size,” Taylor states frankly. “Although the backbone of the production is definitely New Zealanders, very clever individuals were brought in to assist in areas where we had less experience.”

Chief among them was Rygiel, who was hired after Stetson departed the project after principal photography had wrapped. Rygiel oversaw the creation of digital effects and the compositing of miniatures with live action and digital characters. “In terms of putting all of the elements together, the show was not yet on track when I came on,” Rygiel explains. “They were just finishing principal photography, and Mark had been [supervising] shooting bluescreen elements and lots of miniatures. I think they brought me in was because the show was heading into the heavy digital stage of things, and my background includes a broad mix of digital and practical. I think we’re up to 450 shots in just The Fellowship of the Ring, and I was told that that particular film would be the lesser show in terms of effects! The first film has more of a potpourri of effects because it has to introduce audiences to all of the different people and lands.”

A blend of ancient trickery and bleeding-edge digital techniques was needed to transform actors Ian Holm, Elijah Wood, Sean Astin, Dominic Monaghan and Billy Boyd into, respectively, the Hobbits Bilbo, Frodo, Sam Gamgee, Merry and Pippin. “[Casting actors of normal height] created a lot of problems, but it’s also one of the most remarkable aspects of the movie,” says Jackson. “Tolkien described Hobbits as being small people with large, hairy feet, so I don’t think little people were what he actually had in mind.”

Visual effects cinematographer Brian Van’t Hul devised the majority of techniques to translate the full-size cast into 3'6" Hobbits. “Brian set up a lot of the scaled Hobbit-move and motion-control mechanics,” says Rygiel. “Sixty to seventy percent of those shots were done in camera and the rest were bluescreen composites. Sometimes we just had giant sets of legs puppeteered past the actors playing the Hobbits to make them appear small. We also used forced perspective to create shots like the one where Bilbo serves tea to Gandalf. It appears as though Bilbo is right across from Gandalf, but he was actually 30 feet behind him; because it’s all set up from the same viewpoint in relation to camera, Bilbo just looks smaller.

“Whenever we had the Hobbits cross over from the foreground to the background, we used two different lenses — one for the big people, one for the Hobbits — and shot them on bluescreen, then comped them together,” Rygiel continues. “Those were tricky to set up, because if we did a push-in with one lens on the normal-size character, we’d have to change the lens to make the actors playing the Hobbits appear smaller, but we’d want the tables and the chairs to match up, as well as the two camera moves. So when we shot the Hobbits, we’d have them on a tricky sliding platform with an oversized chair, and we’d actually move the platform in relation to camera to take out any parallax from the different lens and larger camera move involved. That way, we could actually scale the move by sliding the Hobbit forward as the camera moved in. It’s an interesting mix of techniques that works flawlessly.”

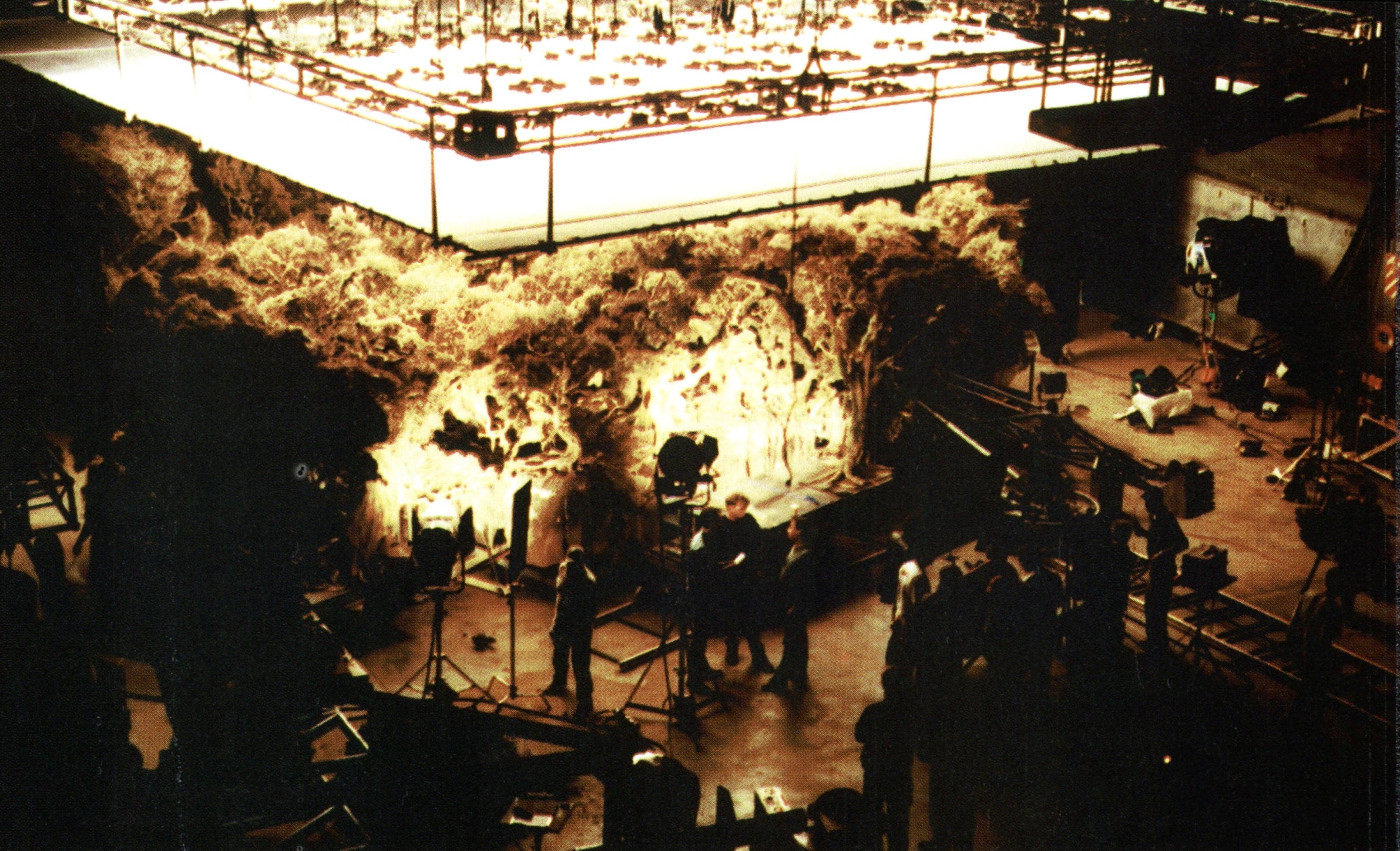

In creating Middle-Earth, Jackson was determined to use real photography instead of CG whenever possible, even if that meant real photography of miniatures. “Computers are a wonderful tool for enhancing things, but I think shooting models is one of the great joys,” the director says. “If I were to have another career, I’d want to build models for films. I love using them and seeing them come together. We had Richard Taylor and his team at Wētā build 60 or more fairly large miniatures for all three movies. Then Alex Funke, our miniatures director of photography, and I could go over the miniatures with a video camera and plot our camera moves. Once the model is standing there in the room, you see angles and great shots that you never even knew about in the early storyboarding stage. It’s like going to a location, and I love the physicality of it. It opens the door to a whole new range of ideas.”

In fact, Wētā artists built 68 vast miniature environments that collectively gave Jackson’s Middle Earth its scope. “We coined the phrase ‘bigatures’ because most of them were massive miniatures,” Taylor says with a laugh. “Each miniature was dictated by the size of the human figure Alan Lee had drawn with the last stroke of his pen, and the environments were colossal, so we needed to build them as big as possible.

“We’ve been fairly precocious in that we’ve tried to pull off extremely small-scale miniatures for a 35mm film,” he adds. “In the first movie, places like [the Elven city of] Rivendell, [the tower of Orthanc at Saruman’s fortress] Isengard, the Mines of Moria and the Pass at Caradhras were all done using 1/12 scale miniatures, or sometimes 1/24 scale, although we built a huge number of settings at 1/36 and 1/72. Saruman’s dark tower of Barad-dur was built at 1/166 scale, and it was nearly three stories tall! Because almost every environment consisted of massive rocks and caves, we started the process by molding interesting rock faces from around the coastline of Wellington, then used a urethane spray gun to spray sheets and dangle the miniature rocks onto massive steel frames. We’d then sculpt any detailing, take a silicon mold and spray it with rigid urethane, which allowed us to build miniatures extremely quickly on a very tight budget. We had a very small miniatures team — the primary group was about seven people — and we made 68 miniatures. Everything was built on wheels and rolled down the road to the shooting stage. We’d hold the telephone lines up to clear the models!”

Rather than creating digital backgrounds for the miniature environments, Jackson employed one of New Zealand’s finest landscape photographers, Craig Potten, who ran all over the country shooting sunrises, sunsets and other magical vistas in order to create scenic background plates. “When you read Tolkien’s books, you can almost think that the characters and story are an excuse for him to describe the landscapes, because landscapes come across very much as being his true love,” says Jackson. “We tried to create very special landscapes with the most beautiful light, because Tolkien always described landscapes at the most beautiful time of day.” Despite the vast number of elements involved in even the simplest establishing shot, a phenomenal amount of previsualization work, spearheaded by animation director Randy Cook from October 1998 through July 1999, helped keep everyone on the same page. Virtually the entire trilogy was laid out in rough animatics. “There were literally three hours of pre-vis for each film,” says Rygiel. “It was so good that there were times when we were trying to final a shot, and Peter would say, ‘Look at the pre-vis. That’s exactly how I want it.’”

One of the first sequences Cook previsualized was the Stairway of Khazad-Dum, where the Fellowship nearly meets its end amid a swarm of murderous Orcs. “Peter and I worked very closely to choose camera angles and choreograph the chase down the stairs, which became a rather elaborate, 140-shot Puppetoon staged entirely with CG characters and CG sets,” Cook recalls. “Peter cut that down to 80 shots, and then the second-unit director, who shot the live-action elements, followed it. The final sequence is extraordinarily close to the pre-vis as far as composition, pace and cutting, even down to the rudimentary gestures I gave the little figures. It was great to block out a big adventure sequence right off the bat.”

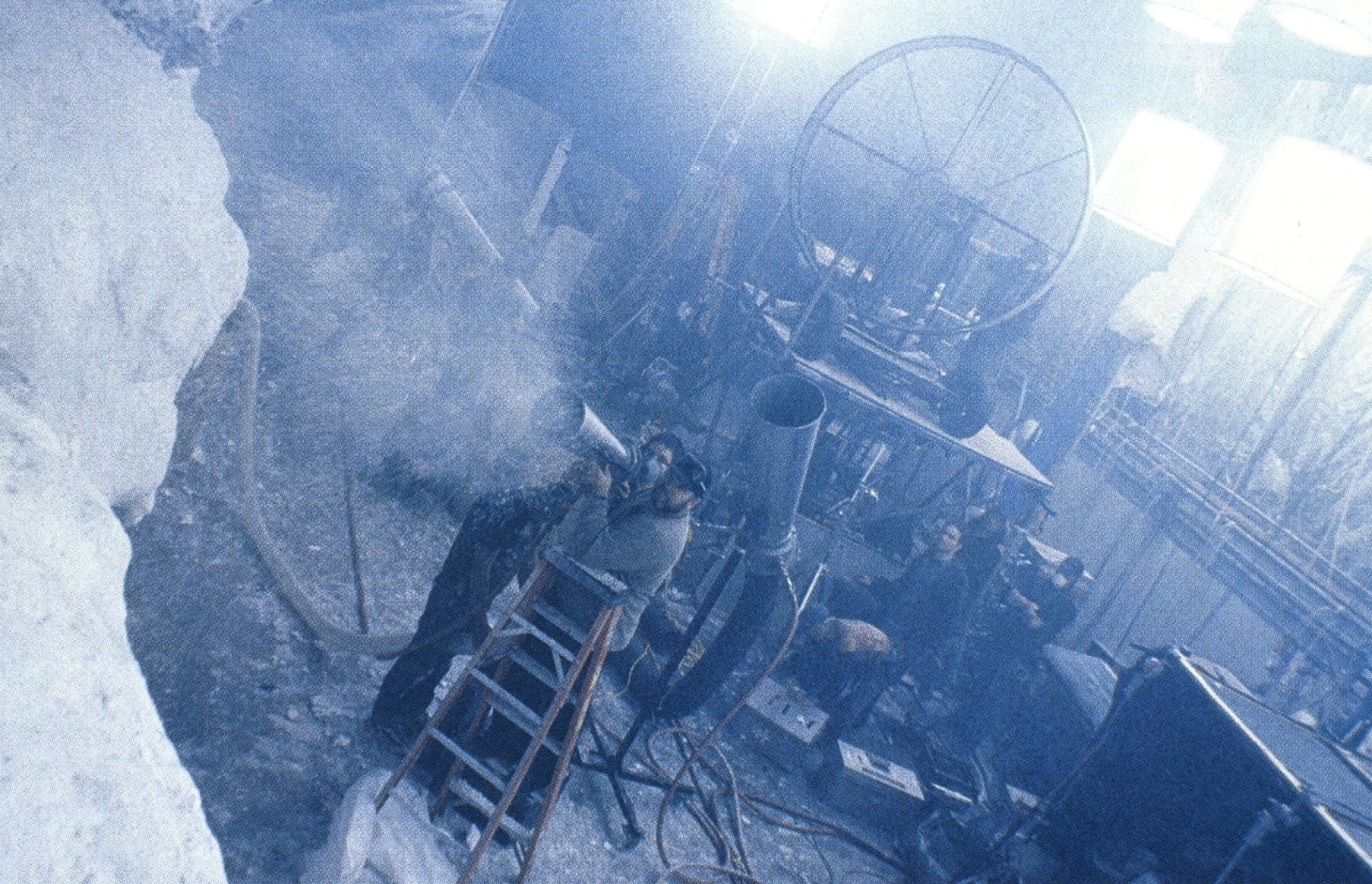

The Khazad-Dum stairway set piece, leading into a fight in the Great Hall and the mine shafts at Moria, was a massive sequence that took almost a year to shoot, and it perfectly encapsulates the problems of combining live action and miniature environments. Miniatures cinematographers Funke, Bluck, Hardberger and Schumann created epic imagery that perfectly matched the live photography by Andrew Lesnie, ACS. “They’re essentially spiraling down through the mines along very precarious walkways that the Orcs have carved over the centuries, and they’re looking up a huge shaft that stretches away into the dark,” says Funke. “It’s lit only by Gandalf’s staff, so we had the classic problem of shooting something that’s supposed to be in total darkness. The members of the Fellowship were either shot against bluescreen or, depending on how close they were, rendered as good digital doubles.”

Meanwhile, the hordes of hobgoblin-like hellspawn called Orcs were required to swarm over the fellowship — a tall order. Although Wētā’s creature shop created about 1,800 Orc suits with matching foam latex and silicon makeup and heavy armaments, the Ore forces envisioned by Jackson were impossible to forge from human actors in costume alone. But swarm they do, thanks to a program developed at Wētā by Stephen Regelous called Massive, which uses motion capture to create cycles that it can multiply into armies of thousands. “You can say, ‘I want my Orcs to charge the humans,’ and once they start clashing, if an Orc stabs a man, he actually falls over and dies,” says Cook, “It took a lot of work to get this system set up, but nowhere near as much as it would have if we’d had to animate 10,000 guys warring.”

“It’s artificial intelligence for sure — or maybe artificial stupidity when it comes to Orcs,” Cook adds with a chuckle. “The Orcs have an extremely complex library of movements, captured in a series of short bites, and then one bite can be blended into any of the others to create distinct actions. We also did keyframe animation of horses and crows, then fed the motion through Massive to make great flocks running around. The Massive shots take from days to weeks to build, depending on how much finessing is involved, and it took a while to render thousands of warriors at high resolution. But I can take very few bows for anything Massive does, because it works very well indeed on its own.”

While things were advancing apace on the digital front, the art of shooting miniatures received a huge boost from a series of innovations, which ranged from homemade motion-control technology to a new way of creating flickering firelight. “The Kiwis are very proud of what they call Number 8 technology,” Funke observes. “Number 8 iron wire is used for everything, so if you can’t fix something with that, you can’t fix it. Visual effects is all Number 8 technology, and we’ve made some amazing jumps on this project. Our brilliant electronics engineer, Chris Davidson, built the best smoke controller ever, finally taming the art of controlling smoke density in miniatures. We’ve tried to use infrared in the past, but unfortunately, the smoke readers work differently on damp days than on dry days. Instead, Chris shot a beam of very low-level red light into a Scotchlight reflector, which sent it back to a sensor to determine the exact density of smoke in the room and keep that density constant.

“Next, Chris designed an interface for the motion control to drive a normal dimmer desk to control lights that need to be dimmed or flickered in miniature sets. Before, we’d attach a motor to a variable transformer to make a single light flicker, but how many variable transformers can you use? To create the effect of a bonfire burning in a cave, you need two lights flickering independently to simulate the randomness of flame, but if you’ve got 40 furnaces burning, each with two lights, you need 40 channels flickering differently. Chris’s system used a 120-channel dimmer desk, and we could put each of those lamps on its own channel, which was controlled electronically from the motion controller. We had 250 steps of dimming that were completely electronic. It’s just so handy, especially if you’re doing any flame effects that have to flicker very slowly because of the motion-control speeds at which you’re shooting.

“Lastly, Brian Van’t Hul, who’s also an effects cinematographer, designed an amazing jump forward in video-assist technology,” Funke continues. “It has a complete workstation to do mattings, splits and wipes, do pre-comps, play shots backward or forward, run them at different speeds to see what they’d look like if we shot them that way, compare takes — and it’s all in one box. It’s all on disk and runs on a Macintosh G4. After the first unit saw it, of course, they wanted one for themselves. Pretty soon, all of the live-action units were using them.”

Van’t Hul and Dominic Taylor also built two motion-control rigs after it was determined that renting commercial rigs would have blown the budget. “They built two complete rigs for what it would cost to rent a rig from the U.S. for a few months, and they worked amazingly well,” Funke says. “I put them in touch with Joe Lewis, ‘Mr. Motion Control’ in L.A., and Joe was very helpful in terms of loaning motors and suggesting techniques. In addition to that, we got one of Joe’s rigs — a custom-built, high-speed model with an extra-long boom — to do the live-action motion-control bluescreen shooting. A lot of the other live-action motion-control shooting was done with rigs built by our mo-co grip Harry Harrison; Moritz Wassman, whose machine shop is inhouse, also built two and a half more rigs. We actually had up to six rigs on the floor at one time.”

But perhaps the greatest innovation was a new motion-control camera designed by Arriflex, at Funke’s urging, specifically for The Lord of the Rings. “We started out with six Fries Mitchells plus my old Rackover, but from the very beginning we talked with Arri about making the 435B an effects-friendly camera because this is basically an all-Arri show,” Funke recalls. “The 435 is steady and has a great viewfinder and a great videotap, but it has never been possible to use it for motion control because it has two motors — one that drives the film transport and one that drives the shutter — and those simply aren’t compatible with the very slow speed necessary to shoot motion control. We in the effects business have been trying to get Arri to solve the problem for years. So, after a lot of very clever engineering, they actually solved the problem so that we can run the 435 at any speed up to 150 fps, or we can unplug the battery, plug in the motion control and shoot at 10 minutes per frame. Although the Mitchell’s shutter just barely covers the aperture, which causes light leaks around the shutter and fogs the frame, the Arri has a built-in capping shutter that simply closes and protects the film when you’re not shooting, which saves a lot of lost frames. We have the first three of the cameras and they’re absolutely fantastic. At last, we can do miniature photography with modern cameras we can see through!

“Of course,” he adds, “the Mitchells and the Rackover were still cranking away, because we only had three Arris and we had up to eight setups running at a time.”

In the end, combining so many effects elements to create the project’s epic canvas was an amazing challenge for all involved. “What’s so different about this project is that you usually know what you’re getting into,” Rygiel says. “This is the first show I’ve worked on that had such a huge cornucopia of every sort of effect; it was a huge conglomerate of CG and practical, miniature and bluescreen.”

“It is daunting, and if you think about it for awhile it almost becomes quite scary,” admits Jackson, who is now finishing the trilogy’s remaining installments, The Two Towers and The Return of the King. “There’s a saying in New Zealand: ’One job at a time is a job of success.’ That became my mantra. You don’t stop and think too much about the enormity of the project; you don’t start shooting the movie and think, ‘In a year and a half, we’re still going to be shooting.’ Instead, you look at what’s happening today and tomorrow and you plan ahead for the next week. You just put your head down and get on with the job. On days when I was getting weighed down by the pressure of it all, I asked myself, ‘Is there anything else that you’d rather be doing?’ And I couldn’t come up with anything.”

Unit photography by Pierre Vinet.