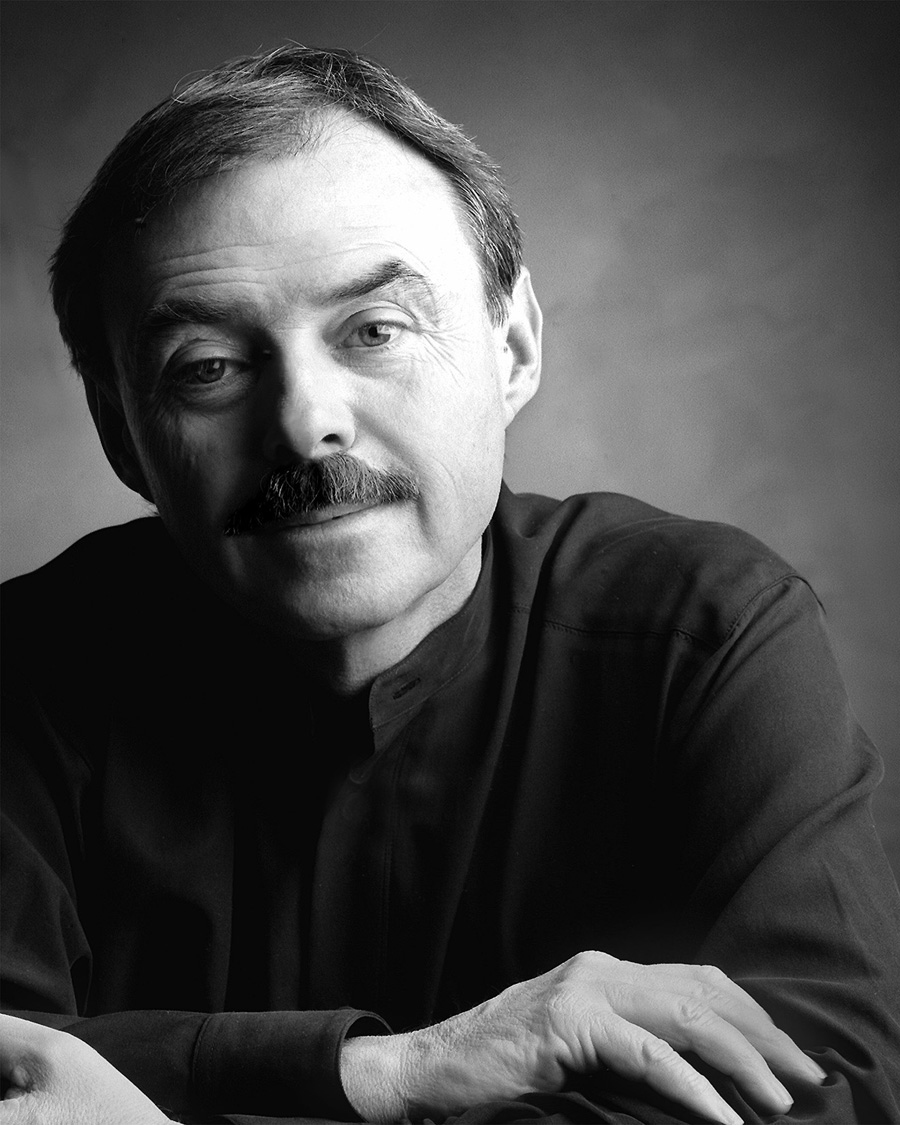

John Toll, ASC: A Legacy of Excellence

After learning from an array of cinematography’s masters, the 2016 ASC Lifetime Achievement Award honoree joined their ranks with his own stellar work.

“I owe a great deal to everyone who gave me an opportunity to learn what this position and profession is about,” says director of photography John Toll, ASC, the recipient of this year’s [2016] Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Society of Cinematographers. The honor was presented during the 30th annual ASC Outstanding Achievement Awards ceremony, held in Los Angeles at the Hyatt Regency Century Plaza on Feb. 14.

“It’s quite a thing to put your life and career in some kind of perspective,” Toll muses while spending an afternoon at the ASC Clubhouse in Hollywood, sifting through a portfolio of behind-the-scenes photographs that document the making of such memorable and diverse pictures as Wind, Legends of the Fall (AC March ’95), Braveheart (AC June ’96), The Rainmaker, The Thin Red Line (AC Feb. ’99), Almost Famous, Captain Corelli’s Mandolin (AC April ’01), Vanilla Sky (AC March ’02), The Last Samurai (AC Jan. ’04), Gone Baby Gone (AC Oct. ’07), Tropic Thunder, The Adjustment Bureau (AC Mar. ’11), Cloud Atlas and Jupiter Ascending (AC Feb ’15). “It’s humbling to think of everyone who helped make this possible.”

Toll, who was invited to join the ASC in 1995, counts such Society greats as John A. Alonzo, Allen Daviau, Jordan Cronenweth, Conrad L. Hall, Haskell Wexler, Robbie Greenberg and Tak Fujimoto among the mentors who helped shape his early career. From them, he says, “I learned it wasn’t just technical aspects that were important. Great cinematography comes from having a passion for telling stories with images and having perseverance in making that imagery a priority. This was as vitally important as technical knowledge or creative ability. The directors of photography I worked for all had different ways of working, but they shared this common attitude: They believed in the integrity of their work. It didn’t matter whether it was a feature film or TV or commercials.”

At the start of his career in the early 1970s, Toll reflects, “I was going to college in L.A. and I got a job working part-time at David Wolper’s documentary production company as a production assistant. I had always been interested in still photography, but I hadn’t been to film school. Working at Wolper definitely put me on the road to filmmaking.

“By the time I left school, I had managed to acquire a minimal amount of experience in the camera department that allowed me to find work on an irregular basis,” he continues. “I was learning something new on every job but pretty much faking it, really. It was all extremely low-budget or no-budget filmmaking. One day I might be working as a second AC; the next I would be working for free, shooting something as a cinematographer and trying to look like I knew what I was doing. One time I even took a job in the sound department as a boom man because I desperately needed the money. I know the sound on that film was awful, but it was a biker-gang movie and the actors usually grunted more than they actually spoke dialogue.

During this time, I met another young person trying to break into the camera department,” Toll recalls. This was future ASC member Charles Minsky, and, Toll adds, “this was his first job in the camera department. I was doing a job as a first AC and he was assigned to me because I was ‘experienced.’ I was happy to have the help, and I told Chuck I would teach him everything I knew. That took a total of about five minutes and then we went to work. We became good friends, and ever since that day I’ve taken full credit for giving Chuck his big break in show biz!”

Eventually, Toll found himself working as a camera assistant for Andrew Laszlo, ASC on the TV movie Black Water Gold. That job gave Toll enough days to qualify for the experience roster and membership in IATSE Local 659, the West Coast camera guild.

Toll’s first job after joining the union was as an assistant to director of photography Archie R. Dalzell for a season of the cop series The Rookies. “Archie was definitely old-school,” Toll says. “When I met him on the first day, he wanted to fire me because I had long hair and a beard, but we were able to get around that. When I had the time, I would hang out with Archie and ask questions. He had great stories about working as an operator on Cecil B. DeMille and Raoul Walsh films. He had been in the business for 40 years but was still enthusiastic about the quality of his work.”

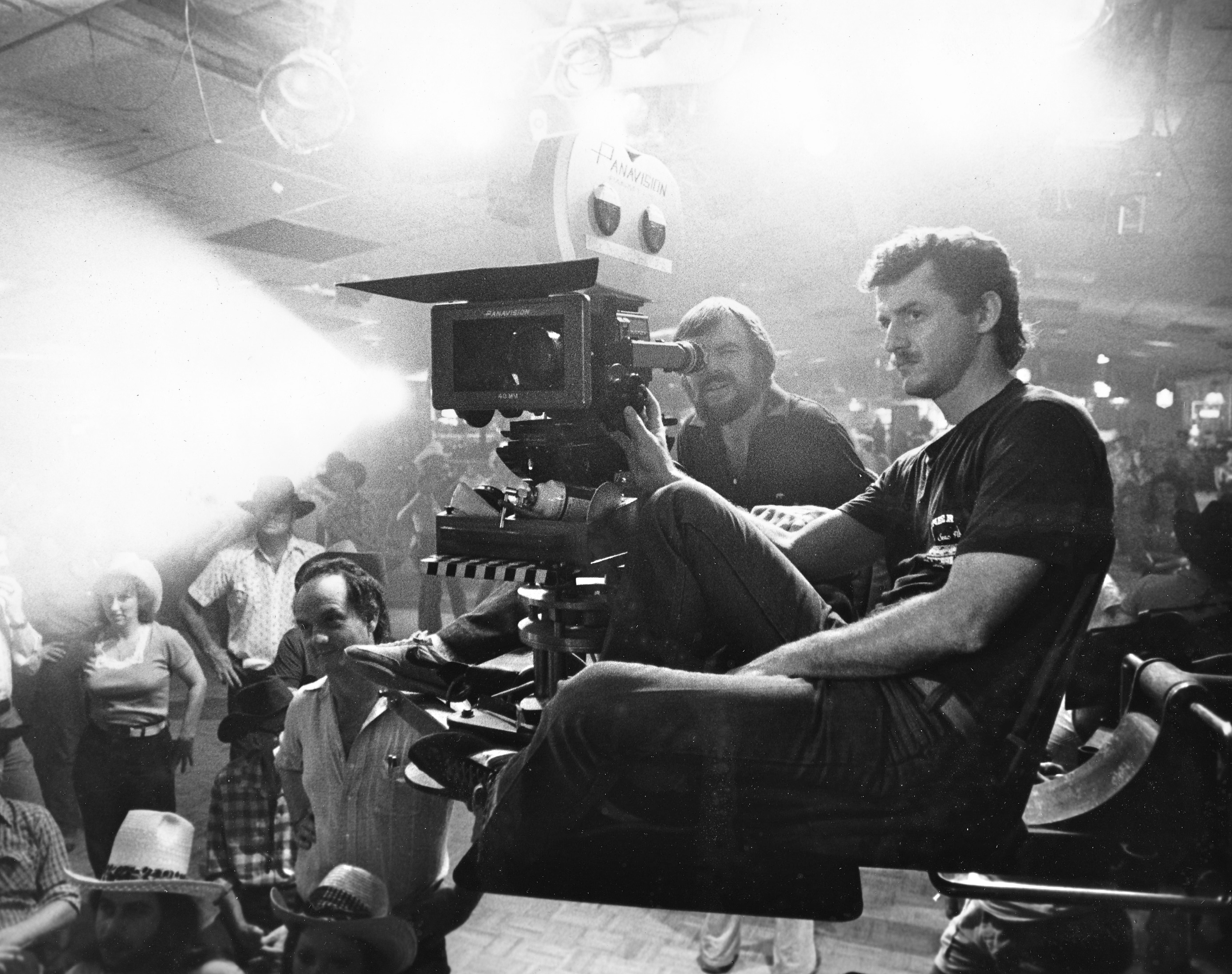

Toll then worked as an AC on TV commercials, eventually for top directors including Melvin Sokolsky and Steve Horn, before getting the opportunity to work as an assistant for John A. Alonzo, ASC on the 1977 thriller Black Sunday. He was soon promoted to camera operator on FM, a feature directed by Alonzo, and he continued with the cinematographer on a long string of features, including Norma Rae, Tom Horn and Scarface.

Between jobs with Alonzo, Toll operated for other seasoned cinematographers, including Ray Villalobos on Urban Cowboy. Interestingly, a seemingly inconsequential credit on Toll’s résumé — the 1980 TV movie The Boy Who Drank Too Much — would lead to another career breakthrough. “This was the first union project that Allen Daviau shot after working for years to get into the camera guild,” Toll explains. “Allen had no regular union crew, so the director — Jerrold Freedman, whom I’d worked with before — brought me in. And Allen was terrific. Not only was his work impeccable, but he was very collaborative and as knowledgeable about the history and craft of cinematography as anyone I’ve ever met.”

Daviau then hired Toll for a small, personal project of Steven Spielberg’s that would become a monster box-office hit: E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. “Allen gave me a call to fill in as B-camera operator on the show,” Toll recounts. “On the first day of shooting, Steven decided that documenting the making of the movie was important, but he wanted it shot on 35mm film. Coincidentally, he had recently seen a documentary shot on 35mm on the set of The Shining. Producer Kathleen Kennedy asked Allen what we could do and he pointed at me, so I was drafted to use the 35mm Panaflex B-camera to shoot behind-the-scenes footage.

“That seemed to go OK, so I came back to the set the next day and was asked to keep shooting behind-the-scenes material,” Toll continues. “Steven seemed fine with what I was doing and appeared to enjoy playing up to the camera. I would follow him around handheld and document him working with the children in the cast, and basically creating E.T. as a principal character. It was incredible observing his whole process.”

After principal photography wrapped, Toll worked with an editor friend to cut the accumulated 50,000' of footage into a 20-minute sample of what an E.T. documentary might look like. He showed this to Spielberg, and, Toll recalls, “he didn’t say a word until the end. Then he said, ‘This is great, but I can’t use it.’ He knew by this time that the movie was going to be huge, and he did not want to compromise the mystique of E.T. as a real, live character. He didn’t want people to see anything that would suggest that he was not a living creature. So that footage was shelved and not used until [a later home-video] release. It was disappointing at the time, but he was quite right in the decision, and it was an incredible, unique learning experience.”

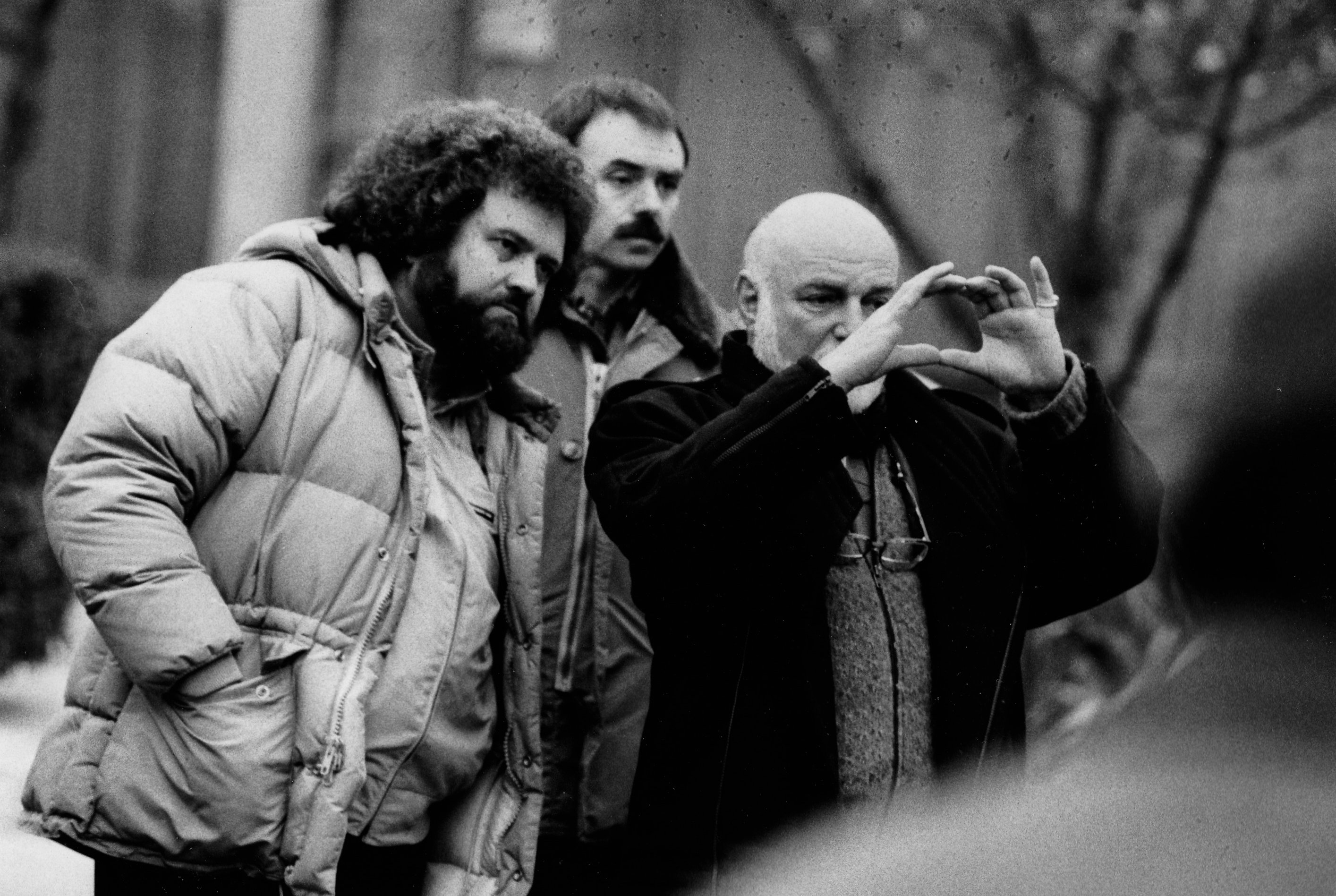

Toll and Daviau would reteam on the anthology feature Twilight Zone: The Movie for segments directed by Spielberg and George Miller, and the spy drama The Falcon and the Snowman, directed by British filmmaker John Schlesinger. “Allen was great to work for,” Toll says. “Not only was he an incredibly talented cinematographer, but he understood how to make the most of the people working with him. He encouraged me to be in all the creative conversations regarding staging and coverage with Schlesinger.”

Another of Toll’s collaborators in the early ’80s was Jordan Cronenweth, whom he met while working on an ambitious Dr. Pepper commercial directed by Melvin Sokolsky. “Melvin had previously worked as an excellent still photographer and usually lit his own commercials,” Toll notes, “but he would call in a cinematographer if the production was really complex, and this one was. So he had Jordan there to oversee the lighting.”

The commercial, Toll explains, was inspired by the classic 1951 Fred Astaire musical, Royal Wedding. “In that movie, Fred Astaire appears to dance up the wall of a room and upside-down across the ceiling. This was originally done with the set built inside a huge revolving drum and a fixed camera inside the set. Melvin had been shooting a series of Dr. Pepper commercials set to music with dance numbers, and someone came up with the idea of a revolving room with several people dancing up the walls and across the ceiling.

“All the previous Dr. Pepper commercials had dolly moves that punctuated the ‘drink shot,’ so Melvin had a dolly designed and built that was mounted on an extension to the revolving set so a camera could move in and out of the room,” Toll continues. “This dolly was remotely operated and capable of doing a move as the set was being rotated 180 degrees. However, the telescoping cranes, remote heads and focus controls that we use today weren’t yet available, so the camera needed to be operated manually. The camera operator — yours truly — and the first AC, [future ASC member] Bing Sokolsky, rode on the dolly through the rotation. At 90 degrees, a tilt became a pan and a pan became a tilt, and when fully upside down, a tilt up on the head became a tilt down on screen. It was pretty wild.

“Safety was obviously a primary concern,” Toll adds, “so we began by securing ourselves to the dolly with a harness and straps. We were definitely safe, but I couldn’t move to operate the camera. Melvin came up with the idea of mounting a piece of speed rail across our laps. We loosened the straps a little, and as the dolly went upside down the bar supported most of our weight across our legs, and with great effort we could move from the waist up. It worked brilliantly, but it’s still the hardest shot I’ve ever operated.”

Cronenweth was also directing commercials, Toll recalls, “and after Dr. Pepper, he called me to do some of these with him. Working with him was amazing. When asked to describe his work, I can only think of the word ‘elegant.’ He had an incredible eye and would always light through the lens and could absolutely see the image as film would see it. He would encourage input and was always excited about his work. His enthusiasm was infectious.”

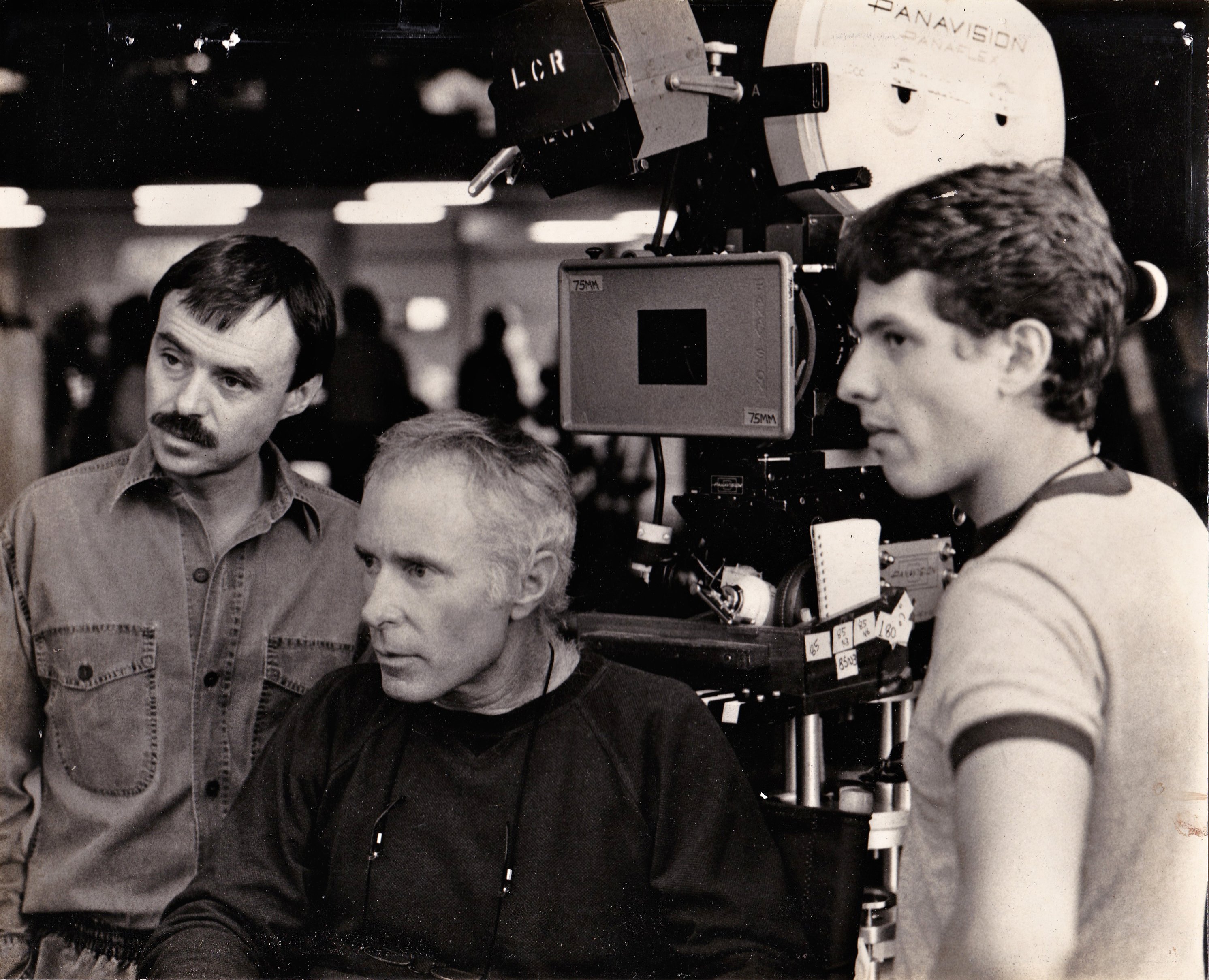

In addition to numerous commercials, Toll would operate for Cronenweth on the cinematographer’s next two features: the drama Just Between Friends, directed by Allan Burns, and the comedic period fantasy Peggy Sue Got Married, directed by Francis Ford Coppola, for which Cronenweth won the very first ASC Award for Outstanding Cinematography.

While operating for Robbie Greenberg, ASC on the feature Sweet Dreams (1985), Toll forged a strong working relationship not only with the cinematographer but his 1st AC, Conrad W. Hall. This led to another turn in Toll’s career, as he received a call to operate for Conrad L. Hall on the noir-inspired thriller Black Widow, directed by Bob Rafelson.

“This was the first feature that Conrad was going to shoot after being on hiatus for a number of years,” Toll says. “He didn’t have a regular operator, and I was recommended to him by Conrad W. It was great to work for him and watch him do his job. He was modest and just honest. He’d tell me, ‘I’ve forgotten how to do this; I don’t know what I’m doing,’ and then turn around and do something that was just brilliant.” Toll would subsequently shoot 2nd unit for Hall on the stylish drama Tequila Sunrise.

At this point in his career, Toll began shooting commercials full time, and he soon met director Rob Lieberman. “He was going to direct the pilot for a Western series called The Young Riders,” the cinematographer recounts. “He wanted to shoot it in a style that was suggestive of a commercial style at the time — a lot of available light and a rough, realistic feeling with beautiful photography.”

Production of the pilot episode entailed a difficult 17-day location shoot near the Yosemite Valley during the winter. “It rained almost every day, but it worked out well, and I got an ASC Award nomination in 1989 for my first long-form project,” the cinematographer notes. “That was a great experience. The day the program aired, I was in Tennessee shooting second unit for Haskell Wexler on Blaze. Haskell won an ASC Award and was nominated for an Oscar for that film. After that, I did one more TV movie and then went back to shooting commercials.”

Given Toll’s growing reputation, it’s no surprise that he began to be offered more opportunities on long-form projects. But instead of jumping at the first chance, he patiently waited for the right one. His break eventually came with director Carroll Ballard’s 1992 sailing-drama Wind.

Already an admirer of Ballard’s previous films — The Black Stallion and Never Cry Wolf, shot by ASC members Caleb Deschanel and Hiro Narita, respectively — Toll first collaborated with the director on a series of commercials. “Carroll was telling me about this project that was going to be shot on 12-meter yachts on rough seas in Australia,” the cinematographer recalls. “It sounded like he had an Australian cinematographer lined up, and I was just listening and thinking, ‘Boy, this film is going to be a nightmare.’ I had some limited experience on small boats and had been unusually prone to seasickness. I thought doing a picture like that would be pure torture. Of course, I told Carroll what a great idea it was and how much fun it would be. I didn’t want to sound negative about this great experience he was anticipating.”

Months later, Wind producer Tom Luddy contacted Toll. “Tom said, ‘Carroll wants to know if you want to go to Australia and do Wind,’” the cinematographer recalls. “I said, ‘Sure, I’d love to,’ but I was thinking, ‘What am I doing?’ But there was no way I was not going to do that picture. Carroll was a director I’d dreamed of working with, and here was an opportunity to work with him on a good picture.

“Two weeks later I was headed to Australia, but I had no idea how we were going to be able to shoot on the boats,” he continues. “I thought I would need to be very clever and scientific about it, but Carroll is a sailor, he knows boats, and he had the absolute right plan, which was to just put the camera on your shoulder and shoot. There was no room for anything else.”

Using then-new compact Aaton 35-III cameras further helped reduce the filmmakers’ footprint, and a special operating point — similar to the one Toll had used on that complex Dr. Pepper commercial years earlier — helped make the impossible achievable. “After one incredibly painful episode in which I had myself ratchet-strapped down to the rear end of the deck, Australian key grip David Nichols came up with a great idea,” Toll remembers. “He built a sawhorse out of aluminum that I could sit on. We could move it around and secure it to various areas of the deck. I had him make a bar that went across my lap that I could press my knees up against to keep myself upright and still be free to hold the camera and operate, just like the revolving room, and it worked great. The Australian sailors immediately nicknamed the sawhorse ‘Trigger’ and put reins on it. It was still a tough shoot for everyone, but we became fairly efficient and even began doing two-camera coverage. Carroll and I each operated because there wasn’t room for anyone else on the boat!”

Wind was not a financial success, but Toll’s expert photography — capturing the excitement and majesty of the subject — caught notice, and Toll was soon introduced to director Edward Zwick as a possible cinematographer for his upcoming Western-themed drama Legends of the Fall, based on the novel by Jim Harrison. Toll knew the book well, and his visual approach was inspired by the still photographer William Albert Allard’s naturalistic work in documenting contemporary cowboys, as well as films such as Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven, shot by Nestor Almendros, ASC. During their meeting, Zwick was impressed by Toll’s take, yet wary of hiring a cinematographer with just one feature credit. But, in the end, he was convinced to take the gamble.

“We put enormous energy into taking advantage of the natural beauty of the locations,” Toll says. “I put great effort into making the lighting feel as natural as possible. This often meant planning how to take advantage of natural light and shooting at the best times of day, but our schedule meant this wasn’t always possible, and we sometimes put a great deal of effort into making it look as if we weren’t doing anything at all!

“During prep,” he continues, “we went through the script and for individual sequences we attempted to designate certain times of day, or even weather conditions, as a way to support various parts of the story. We weren’t always able to stay with this plan, but Ed Zwick and first AD Nilo Otero went to great lengths to support this idea as much as possible.”

Toll’s efforts in Legends earned him widespread praise, the Oscar for Best Cinematography, and ASC Award and Camerimage nominations. But months before the film even premiered, it angled Toll’s trajectory further upward. Actor Mel Gibson was prepping his second directorial effort, the epic drama Braveheart, and, Toll says, “Mel was casting the movie and asked Ed Zwick if he could see some film of the actors in Legends of the Fall, which was still being edited. After Mel looked at about a half-hour of the film, I received a call to meet him. They said he was directing and starring in a movie in Scotland. It sounded quaint — I thought it couldn’t be very complicated if he was directing and acting in it. Then they sent me the script about two hours before I met Mel. Legends of the Fall had some limited battle scenes, so I understood how complicated they could get, and I was reading this script thinking, ‘They can’t be serious...?’”

During their dinner meeting, the enthusiastic Gibson peppered Toll with questions about how he envisioned approaching the ambitious story. Gibson was impressed, and, like Zwick before him, took a chance even though “Mel could have hired any one of a dozen great cinematographers with experience on huge movies,” Toll remembers. “I kept asking myself if he was going to wake up one morning thinking what a mistake he was making!” But the collaborative result was nothing short of breathtaking, and the film would earn numerous accolades, including Toll’s second consecutive Academy Award and the ASC Award for Outstanding Cinematography.

“Suddenly people were asking, ‘Who the hell is this guy?’” Toll says with a laugh. “However, by that time, I just intuitively knew how to do things, in part because I’d learned a creative process from some of the best in the world.”

Toll’s more recent credits — from the pilot of the hit series Breaking Bad; to the snarky superhero-adventure Iron Man 3; to his current project, the edgy and out-there sci-fi series Sense8, created by his Cloud Atlas and Jupiter Ascending collaborators Andy and Lana Wachowski — reveal an artist still striving not only to tackle new creative challenges and master new technology but also have fun while doing it.

“Revisiting some of my work in connection with this award from the ASC, it’s hard not to think about going back and reshooting various things,” Toll says. Asked if there was a particular project he would like to revisit for a creative makeover, he smiles, and after a brief pause replies with a laugh, “Probably most of them! Why does that scene look that way? What was I thinking? When it’s good, it feels really good, but getting overly impressed with your own work is probably the worst thing that can happen to your creativity.”

Since 2016, Toll has added to his resumé with projects including Harriet, Billy Lynn's Long Halftime Walk, and The Matrix Resurrections. Presented with their Lifetime Achievement Award by the Camerimage Film Festival in 2017, Toll spoke with AC about that honor.