Makeup Effects for The Hunger

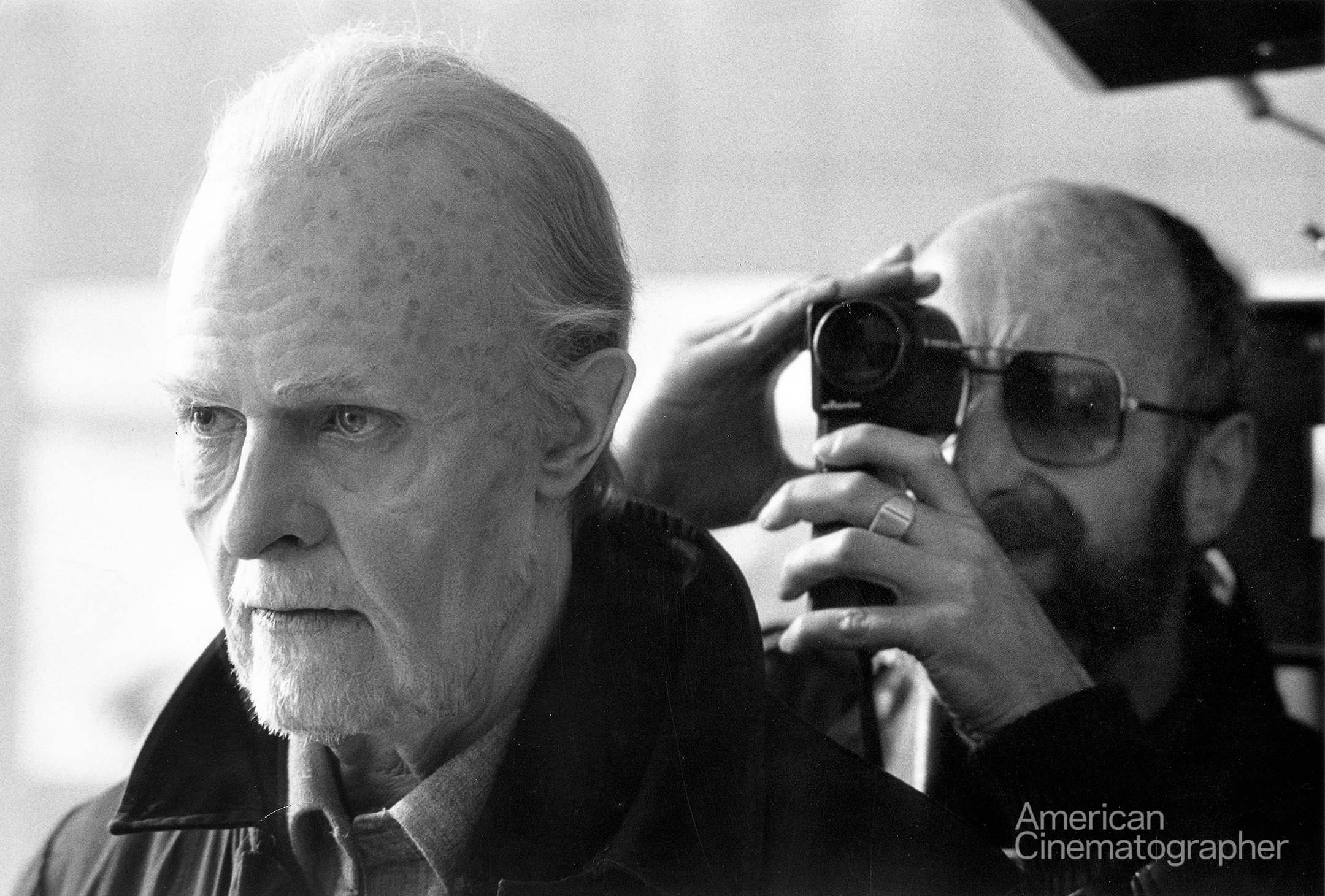

“Doing the series of makeup progressions on Bowie was the main reason why I took the film, because that opportunity is so rare,” says makeup expert Dick Smith.

This article originally appeared in AC, Aug. 1983. Some images are additional or alternate.

The art of special makeup effects (easily, the devil’s art) has taken quantum leaps and bounds in the past five years. Burgeoned by a new wave of macabre films requiring explicit images, an oddball technology of prosthetics, foam latex appliances, inflatable bladders, hydraulics, and cable control has made possible the “on camera’’ transformation effect. Jekyll now becomes Hyde without relying on the old standby of lap dissolves, and cat people emerge from their human cocoons with a minimum of cheato’s. Anyone who has seen Altered States and the remake of The Thing knows that there is virtually no limit to what can be done with this bag of tricks.

With understatement, Dick Smith is the pater familias of the field. Artists technologists Rick Baker, Rob Bottin and the like owe their careers to his influence and guidance. During his 14-year reign over the NBC makeup department, Smith began using foam latex facial appliances for a TV presentation of Alice in Wonderland (1955) and since then has honed it down to a science. Though largely recognized for his masterworks of grotesquerie as seen in the The Exorcist and The Sentinel, Smith’s true metier is old age makeup. Sculpturally, he is peerless in that regard. Witness House of Dark Shadows, Little Big Man, The Godfather, The Sunshine Boys, Hal Holbrook in Mark Twain Tonight!, to name only a few. Thus, when producer Richard Shepherd decided to put Whitley Strieber’s The Hunger on the screen, Dick Smith became an immediate consideration.

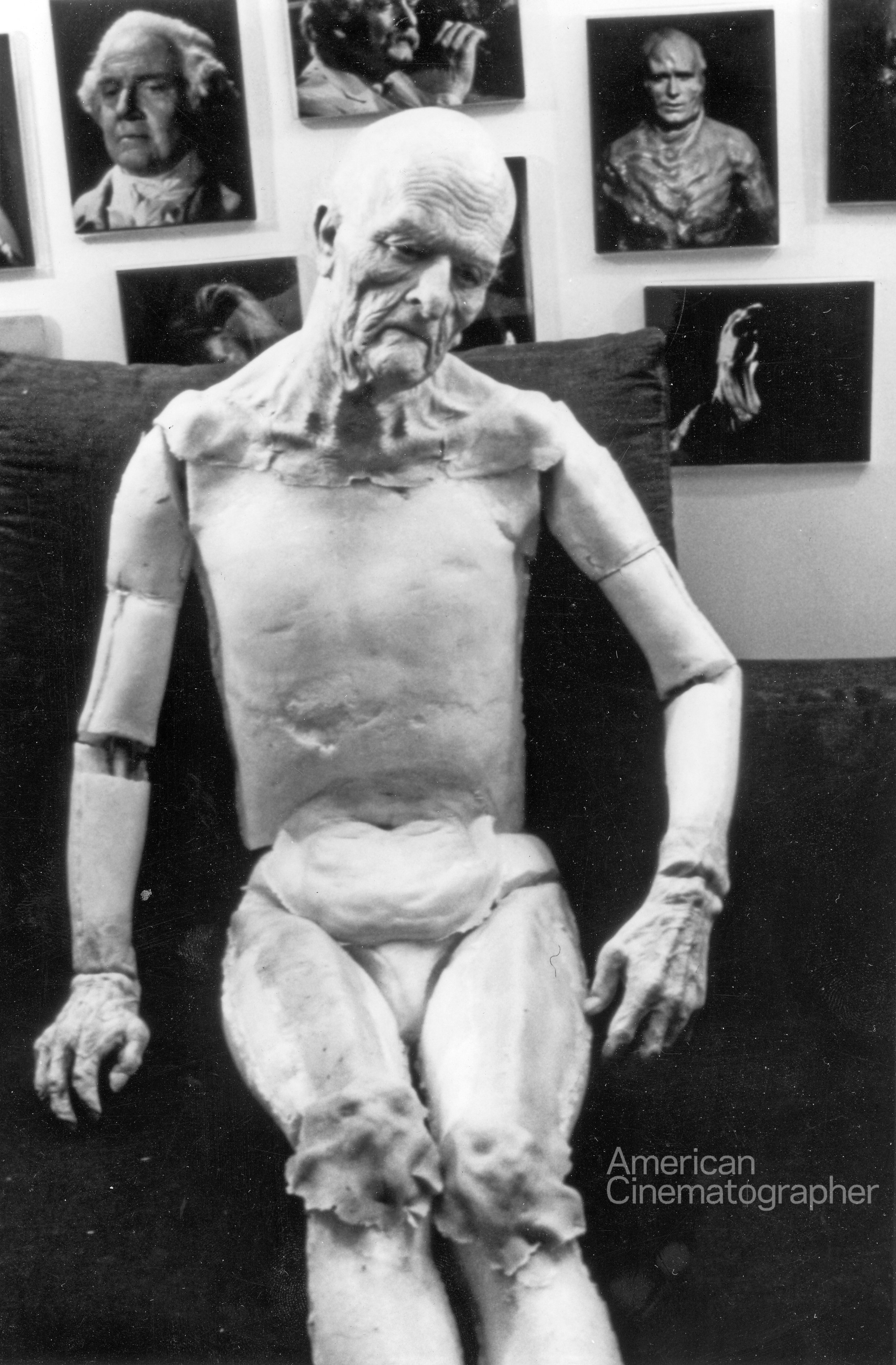

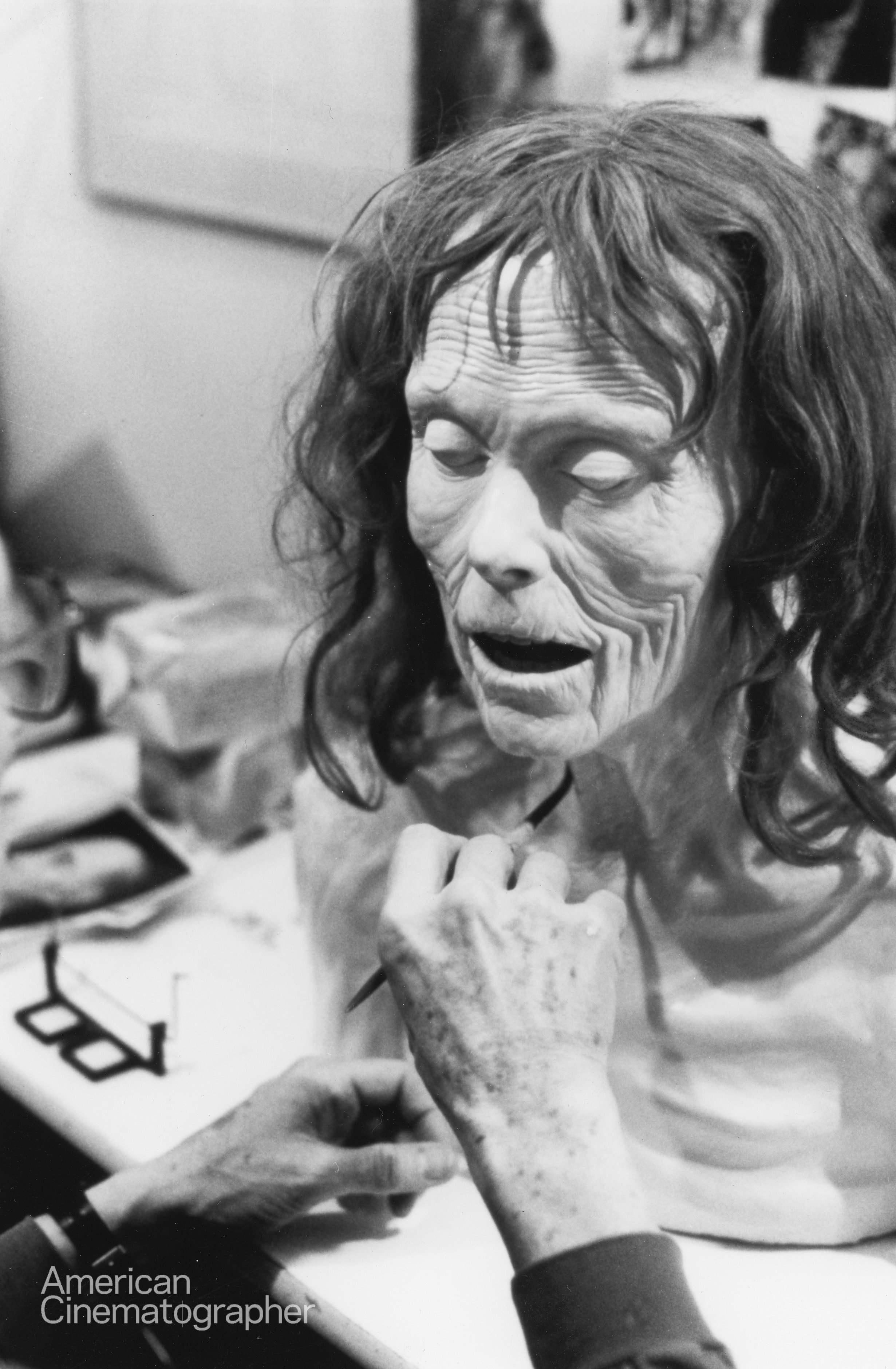

The film revolves around the existence of an eternally beautiful woman (Catherine Deneuve) who is actually the matriarch of a race of vampiresque beings that feed on human blood to achieve immortality. Her present-day consort (David Bowie) is periled by the sudden rundown of his biological clock, and in a matter of days deteriorates from age 30 to 150 and beyond. Placed in a coffin, he resides forever in an attic with Deneuve’s former lovers, who apparently remain in a limbo-death state. For The Hunger's climax, the mummies are reanimated and crumble to bits when Deneuve is mortally wounded by her female lover (Susan Sarandon). Deneuve then decays into a ghastly, writhing horror.

“Frankly,” says Smith, “doing the series of makeup progressions on Bowie was the main reason why I took the film, because that opportunity is so rare. I did it once before for a Sucrets commercial, where a dozen makeups were dissolved into a 30-second spot showing a man going from caveman to futuristic super-intellect. But it was a quick job, and done rather badly. All of Bowie’s makeups survive in the film, and I’m quite pleased with them. As far as the mummies are concerned, I had some theories on how to do this. Unfortunately, the theories didn’t match the realities at all! That, really, is what put all the pressure on us. I thought the R&D stage would be done in a month, including film tests, But we didn’t know where we were going until 2½ months later. And we plunged into everything at once.”

Smith’s contractual arrangements with producers are unique. Home based in suburban Larchmont, New York, all mold-making and casting operations are done in his basement workshop. When the foam latex pieces are painted and ready, he flies to the location or studio (London’s Shepperton, in this case) and applies them to the character, working closely with the director and the cinematographer, making suggestions to enhance the filmic appearance of his work. Such was the case with David Bowie, who spent many moments under a claustrophobic facial mold in Smith’s “black museum.”

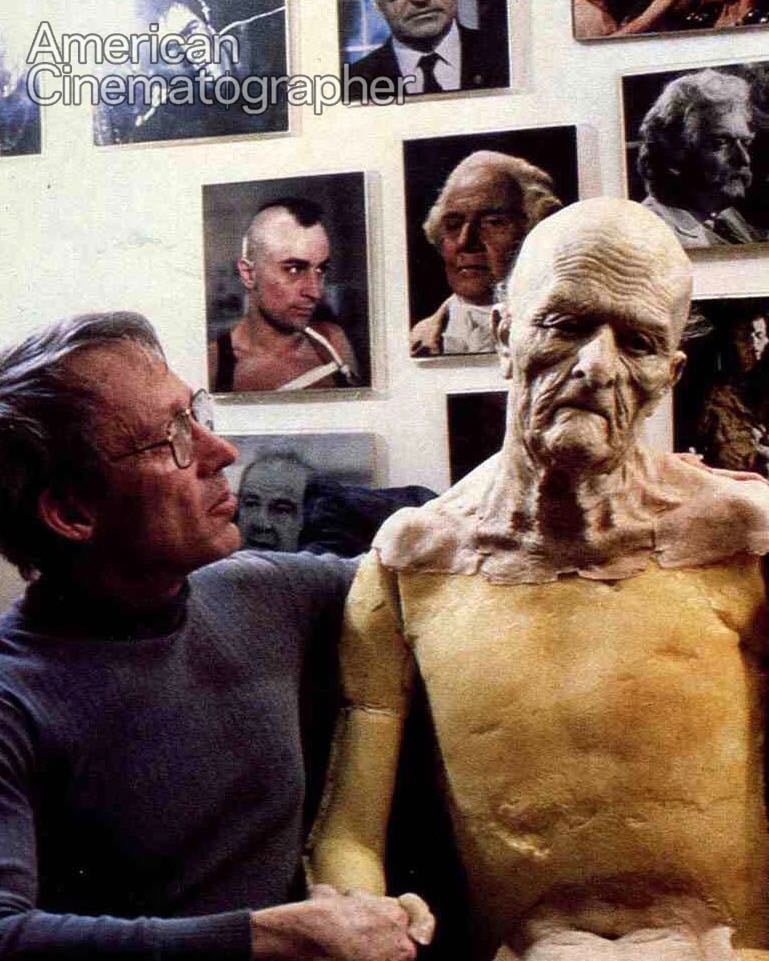

The technique is fairly standard, with variations innovated by Smith. First, a two-piece mold is made of the actor’s head and neck using flexible alginate. Hydrocal plaster is poured into the mold, resulting in a perfect bust of the actor. Aging features are sculpted in plastilene clay over the bust. Smith then employs a crucial intermediate step: the clay overlay is sectioned off with a blade and the whole head is dunked into a tub of cold water, enabling the clay pieces to harden and peel off intact. Positive molds (sectional duplicates of the life mask) are then prepared as backings for the clay pieces using a different brand of plaster (Ultracal 30). Negative molds are made in turn by pouring the Ultracal mix over the clay. Finally, foam latex is injected into the negative molds, resulting in perfectly contoured facial appliances. (Smith uses a special foam formulated by the late George Bau, distributed by Charles Schram in Hollywood, and the castings are extremely lightweight). The appliances are trimmed and painted in credible flesh tones; blemishes and hair are added to enhance their verisimilitude. Then the pieces are fixed to the actor with special adhesives and blended together, permitting a full range of facial expressions.

The final effect is uncanny. Though the resemblance of David Bowie’s makeup to Dustin Hoffman’s Little Big Man may seem rather obvious, Smith’s sculptural sense perceives them as being far removed from each other.

‘‘The ages were basically 50, 65, 75, 90, and 150,” says Smith. “Prior to age 50, the regular makeup artist, Ann Brodie, applied appropriate facial shadows to telegraph the aging process. I recolored his 150-year-old appliances to 200, making it look mouldier. The color change appears when he is placed in his coffin by Deneuve.

“A young man was brought in when I appeared for the effects application in England, Nick Dudman. He did such niceties as the throat being cut, when Sarandon stabs herself in the neck. Nick did those things very skillfully, all the ‘gore’ appliances and blood rigging with the materials I provided.”

“Bowie was a complete appliance makeup, as it was with Little Big Man,” Smith states. “But I took one set of appliances and put them together as a slip-on mask for a stuntman, for the final scene where the mummies look over the broken bannister at Catherine. He was used in a couple of shots when Bowie had already left. For the shot of Deneuve carrying Bowie to his coffin, a special dummy was constructed wearing the same mask. Actually, I had less time to do all five or six makeups than I had to do the one for Little Big Man! Of course, I can work a lot faster now than I did in 1970 due to improved materials. Unfortunately, Bowie’s makeups were not really finished with the loving care that I was able to expend on Little Big Man. I just didn’t have the time. Also, on The Hunger, I had molds that deteriorated due to the inferior quality of modern gypsum. I lost a lot of surface detail, which was upsetting”

Smith generally works well with directors, but aesthetic differences inevitably pop up. Chrome-plated egos are hard to penetrate, and directorial stands are often difficult to flex. Such was the case with The Hunger. Its director, Tony Scott (his first feature), decided to let Bowie’s beard grow for scenes preceding Smith’s appliance job. Smith immediately protested via long distance and apparently talked Scott into dismissing the idea. The conversation came to naught when Scott later told Smith that he couldn’t devise a logical reason for Bowie to shave, an excuse possibly predicated on Scott’s refusal to re-shoot those scenes.

“Normally you can’t glue stubble onto an appliance coated with rubber mask grease paint,’’ Smith explains. “The stubble covered his jawline. Fortunately, I had been developing this rub-proof, tremendously adhesive paint that would work both on human skin and appliances. It came about during my early experimentation with Dustin Hoffman’s Tootsie makeup in order to deal with the problem of concealing Dusty’s five o’clock shadow, and from keeping the makeup from rubbing off on his dress, which was originally a white nurse’s uniform! [Smith was on Tootsie with director Hal Ashby. When Ashby walked, so did Smith.] So the paint was partially developed. I went on The Hunger right after I left Tootsie, and was thankful that I had experimented with the adhesive paint. As it turned out, I had no choice but to apply the stubble, and it worked out fine. I’ve now given up the old rubber mask grease paint entirely in favor of this new formulation, except for around the eyes, because it’s damn hard to remove.’’

In addition to the appliance work, Bowie wore belly pads, a back hump, and special knee pads to create the illusion of boniness. Bowie, a skier, has heavy upper legs, making all of the camouflage work imperative. Contact lenses completed the effect. Smith flew to England in April 1982 and transformed Bowie before Stephen Goldblatt’s camera during a three-week shoot, while his expert mini-crew back in Larchmont worked at breakneck speed on myriad of other problems.

The production’s time constraint proved to be Smith’s major source of heartburn. The Hunger began in the fall of 1981. Initially, he estimated that the job could be completed in six or seven months. He managed to talk producer Richard Shepherd into allowing him to bypass the shooting schedule, wincing at the memory of his entanglement during the production upheaval on Altered States. Here, Smith was faced not only with doing Bowie’s appliances, but fabricating a cadre of living corpses (which ultimately had to crumble) and a grotesque mechanical likeness of Catherine Deneuve as well.

“Because of the problems involved, I had to go to the director and reveal that we couldn’t be as ambitious as we had planned, that maybe the problems could be resolved if we had an extra six months and more money. But we couldn’t under the circumstances. Finding that I had underestimated the amount of work, I tried to get more help. The producer was on an extremely tight budget, and MGM was in bad financial shape at that time. So I came up with a ball park figure for extra salaries and materials. Sadly, I found myself locked into a budget and schedule, with no give.’’

Bowie’s makeup progression was a piece of cake compared to the disintegrating mummies. As the end sequence unfolds, Deneuve’s former lovers (including Bowie) crawl out of their coffins, gather at the upstairs landing, and watch Deneuve decompose in agony as she falls over a bannister. One by one, they begin to crumble — heads fall off, bones shatter, while Deneuve becomes one of their own number.

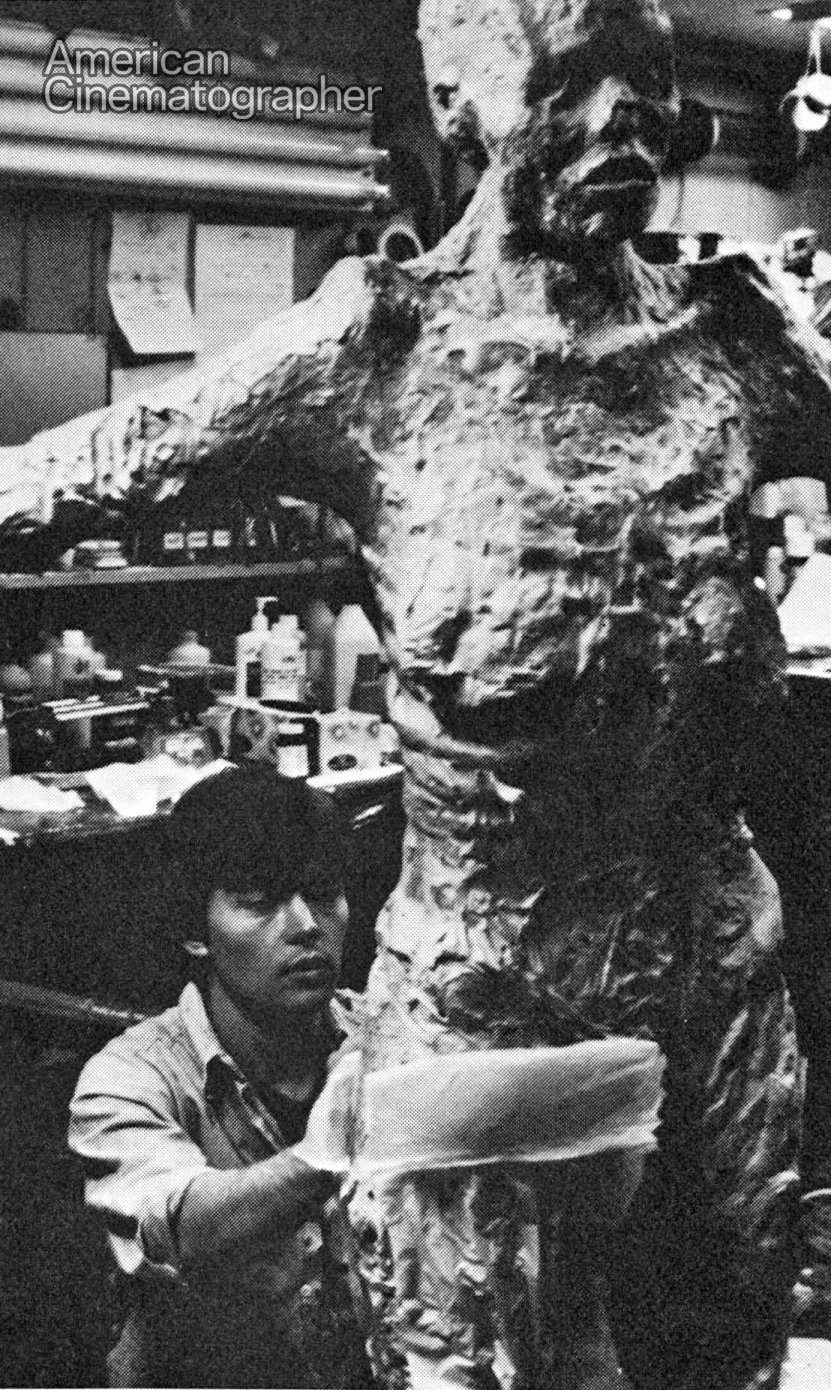

At first, Smith planned on going with articulated mechanical figures for the bulk of the montage, using actors in mummy suits exclusively for long shots. However, during choreographic discussions with director Scott, it was decided to nix the mechanical approach and use actors in body suits exclusively, up to the point of disintegration. Smith modeled his cadavers after the famous Guanajuato mummies in northern Mexico, which are braced upright against cavernous walls. Of course, the obvious question arises: How does one make a performer look like an emaciated mummy?

“We had special casting sessions to find nice, skinny, healthy people,’’ Smith explains. “No anorexics or anything like that. It happened through casting directors and word of mouth. Only one or two of them were actually performers.

“We worked out some very effective full body suits that looked good on camera. We did the simplest thing, which was to cast the body of each person lying down, from neck to ankle. Arms and legs were cast separately, as were the hands and feet. We then had leotards fitted to those people with a zipper up the back. We would then build up the kneecaps and bony areas with blobs of cotton. For the rib section, we made foam latex appliances that were strapped onto their slender bodies.”

When Smith speaks of “we,” he is usually referring to Carl Fullerton, a young and extremely talented makeup effects artist who had collaborated with Smith on Altered States and Ghost Story. For Altered States, Fullerton, under Smith’s guidance, developed the micro-thin bladder system used to create bulges and ripples under a foam latex appliance. For The Hunger, he was primarily involved with fabricating and detailing the mummy suits, as well as experimenting with and developing materials for the crumbling effects.

Smith and Fullerton worked out an ingenious system for creating grotesque wrinkles on the suits. A layer of foam latex was applied to each performer’s leotard; over that was placed a large plastic drop-cloth. The plastic was manipulated into various wrinkle shapes and peeled away. ‘‘We would do the whole body that way,” says Smith, ‘‘cutting pieces from here and there. It required maybe ten batches of foam latex to cover all the bodies. The heads were done in the usual fashion, by making molds of the actors’ faces and casting them up. Ultimately it became one big suit.”

The crumbling mummy operation required entirely new lines of thinking. Nothing like it had been done before. The idea was insidiously deceptive, even for Smith. ‘‘All this time, we were trying to get something out of Hollywood called gypsum snow. But we couldn’t get it. We got excuses from the manufacturer, but had no time to nurse a waiting period. It might’ve been the ideal thing, we thought. But on reflection, it probably would’ve disappointed us. Gypsum snow is used for prop bricks that crumble. We needed something much weaker than that.”

Fullerton experimented with hundreds of substances and fillers, trying to develop a material that would hold its shape yet pulverize easily. Eventually he stumbled across a supply of foam latex that had been poorly mixed by the manufacturer, resulting in a cast that was porous and crumbly. Fortunately, for their purposes, the company was able to reproduce it in quantities. In order to have it pick up detail from the mold — it couldn’t on its own — Fullerton combined it with brittle wax and microballoons (tiny glass beads ordinarily used to create a light airway during the casting process). Being made of glass, substances don’t adhere to it well. That helped make the wax even more fragile. Baking soda and vinegar was added to the wax and brushed in a thin layer into the mold to capture detail. Vinegar caused the soda to give off gas, making the wax spongy. Then the entire witches’ brew was poured in and allowed to set.

‘‘Each experiment had its own problems,” sighed Smith. ‘‘You’d have a marvelous material made of microballoons and it would be great when you first removed it from the mold. Three days later, upon losing its moisture content, it would disintegrate! On the other hand, some materials came out of the mold satisfactorily, but as they dried, they became too tough. So you go through incredible combinations, then search for more.”

Castings from the mixture were so fragile, special molds had to be invented to separate them without breakage. ‘‘We developed molds which I’d never seen before.” They consisted of two layers of flexible material and the traditional mother mold, designed to disassemble in many pieces to avoid stress on the cast. Naturally, all the mummy casts had to be made at Shepperton Studio, as transporting them would have been impossible. ‘‘We had around 50 crates sent over to England,” Smith recalls, astonishingly. ‘‘Molds, materials, all those bloody mummy suits and dummies. The shipping and packing alone ran into six or seven thousand dollars.”

Once the casting process was completed, then came the problem of figuring out how to make them crumble on cue. An idea was suggested to Smith by Bran Ferren, creator of visual effects for Altered States, of employing a sonic vibration table, a device conventionally used for industrial purposes to test metal fatigue. The scheme was to anchor the camera onto it along with the casts so the motions would be in sync. The table would literally shake the hell out of the sculpture. Unfortunately, Smith had no way of proving it out: ‘‘There was no time or money to rent facilities at some laboratory and experiment with it. On a bigger budgeted film, it might’ve been advantageous to buy or rent it and transport it to the studio. I just gave up on exotic means of dealing with things that we could handle in a conventional way.” Smith and Fullerton managed by disrupting the casts with unseen rods, wires, and hands. The cuts were judiciously edited.

One clever shot had a male and female mummy keel over and collapse in a corner. The male’s head drops off into his own chest and crumbles with the legs. To achieve this, actors in full body suits performed the choreography. Casts of them were made in their end positions and dummy duplicates were fabricated. The head of the male had a piston running through the neck area into the midsection. The back was open. Then Fullerton stuck his arm through the wall into the chest area and yanked down on the piston for a grand guignol decapitation effect.

The greatest conceptual gulf between Smith and director Scott revolved around the idea for Deneuve’s grisly demise. Smith’s concept was that she and her lovers were two different animals. They were born mortal; she was a purebred of her race of creatures. ‘‘I figured that when she would decompose, the results would be different. The mummies were merely supposed to resemble desiccated human beings. But I felt Deneuve needed to reveal her true monster underneath. You know, something special. In that lay my notion of having her facade slough off like a seven-year locust and her true image emerge — a hideous, toothsome thing that really looked animalistic. That, too would disintegrate into a truly malevolent creature.”

Smith went so far as to build a detailed model of the tooth-head in an effort to convince Scott of its merits. But Scott abandoned this approach, possibly to avoid connection with a similar makeup effect engineered by Tom Burman for Cat People, and instructed Smith to conform it to the crumbling mummies.

Nevertheless, Smith did manage to concoct a whopping, nightmarish apparition that telegraphed Scott’s conventional image. He constructed a grotesque head-and-shoulders dummy of Deneuve capable of thrashing back and forth on the ground via a series of cable controls. Not satisfied with mere eye, jaw and tongue movement, he developed a new technique to distort the entire shape of the head without the use of bladders. “By incorporating a flexible skull, we could get distortions inward as well as outward, by pulling the skull in,” he explains. “The thing looked so bloody real! We could make the right temple cave in and the left jaw push out, all at the same time. The whole head wobbled like a funhouse mirror without the use of opticals.”

The fate of Smith’s creative efforts followed a behind-the-scenes scenario similar to that of Altered States. Getting stung by the director was nothing new. Scott, ostensibly flaunting his background steeped in arty television commercials, decided to over-crank the camera and use the hair sloshing in slow motion as a primary image. “That’s fine for the crumbling stuff,’’ Smith points out. “But here we have a human head shifting from side to side, going through changes. And when you slow that down, you don’t see the change happening. Furthermore, we couldn’t have sped up the action of the head, had we known of Tony’s intentions, because we were working with pulleys and cables. By the second day, we virtually wrecked them. By working them so bloody hard and fast, they finally just gave out.’’

In the film, the thrashing head dissolves to a duplicate-move mummy head, punctuating the montage. All the while, Smith had some transitional effects brewing. A second Deneuve head was devised in a more advanced state of decay than the first, which incorporated a protruding cheekbone. When retracted, the stretched latex skin would appear to wrinkle for a rather neat segue. It was part of a “wrinkle program’’ Smith was trying to achieve, one of many experiments which included the application of heat to a filmy material painted onto the head. That one failed, but the protruding cheekbone effect was successful. Regrettably, Smith does not have much control over sequences involving his own makeup effects. It never made the final cut: “I presume that in the editing, Tony just didn’t have the time to fit in all the things we had done. The realities of editing lead to serious compromises and deletion of material. That marvelous transition is something that audiences will never see.’’

A more ambitious casualty was Deneuve’s shriveling legs, essentially a carryover from a shriveling arm effect Smith devised for Altered States. Leg molds of actress-sculptor Julie Prince were made and foam latex skins cast from them, about 3⁄8 of an inch thick. “This was fitted over a skeleton and a fiberglass upper end which was airtight,’’ Smith explains. “It had black silk stockings and garters, very sexy, and there was a bit of ass showing. We had a complicated air system which, with very slow pressure, maintained them in solid form. Then, by a reversal of certain levers we turned on this very powerful vacuum. It would instantly suck air out and draw the skin right down to the bone. We also had cables inside which would pull the skin in different directions, so the folds would have a natural irregularity to it. That helped. You could slow it down and operate it at any speed. But it looked more effective as it happened. Bang! Unfortunately, as photographed, the lighting on the legs looked harsh. We were stuck with it for the scene. It hardly flattered them.” Scott opted to scrap those shots, save for one static cut.

“I should mention that Catherine Deneuve was marvelous and a terrifically good sport throughout,” says Smith. “She went through a lot of tough stuff toward the end, especially in scenes involving blood, but she never complained and often laughed about it. Which is perhaps all the more surprising, because she appears to be kind of aloof. Yet she isn’t at all, personally.”

Despite certain structural weaknesses in the screenplay, The Hunger is a stylish, surprisingly sensual horror trip. Relaxing in his Larchmont workshop while his Hunger creations leer at him harmlessly, Smith takes his triumphs and disappointments in stride. During quiet moments, he will complain about his own biological clock running down. But one need not do more than blink and he is off on another movie. “Films like this can be pretty rough in the pressures they put on you. It’s very easy to have your health and patience break down working month after month, seven days a week without a break. You’re looking at the calendar pages flying by and you know you have to deliver the damn stuff. And it’s taking much longer than it ever could. You just have to deal with it without blowing your top.”

Smith recently returned from assignment in Czechoslovakia, where he adhered some remarkable foam latex appliances to the lead actor in Milos Forman’s forthcoming feature Amadeus. Shucking his usual modesty, Smith claims that the old-age makeups for that film are the best he’s ever done.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.