Third Round for an Ongoing Nightmare on Elm Street

Roy H. Wagner films the return of Freddy Krueger as he battles The Dream Warriors.

This article originally appeared in AC May 1987. Some images are additional or alternate.

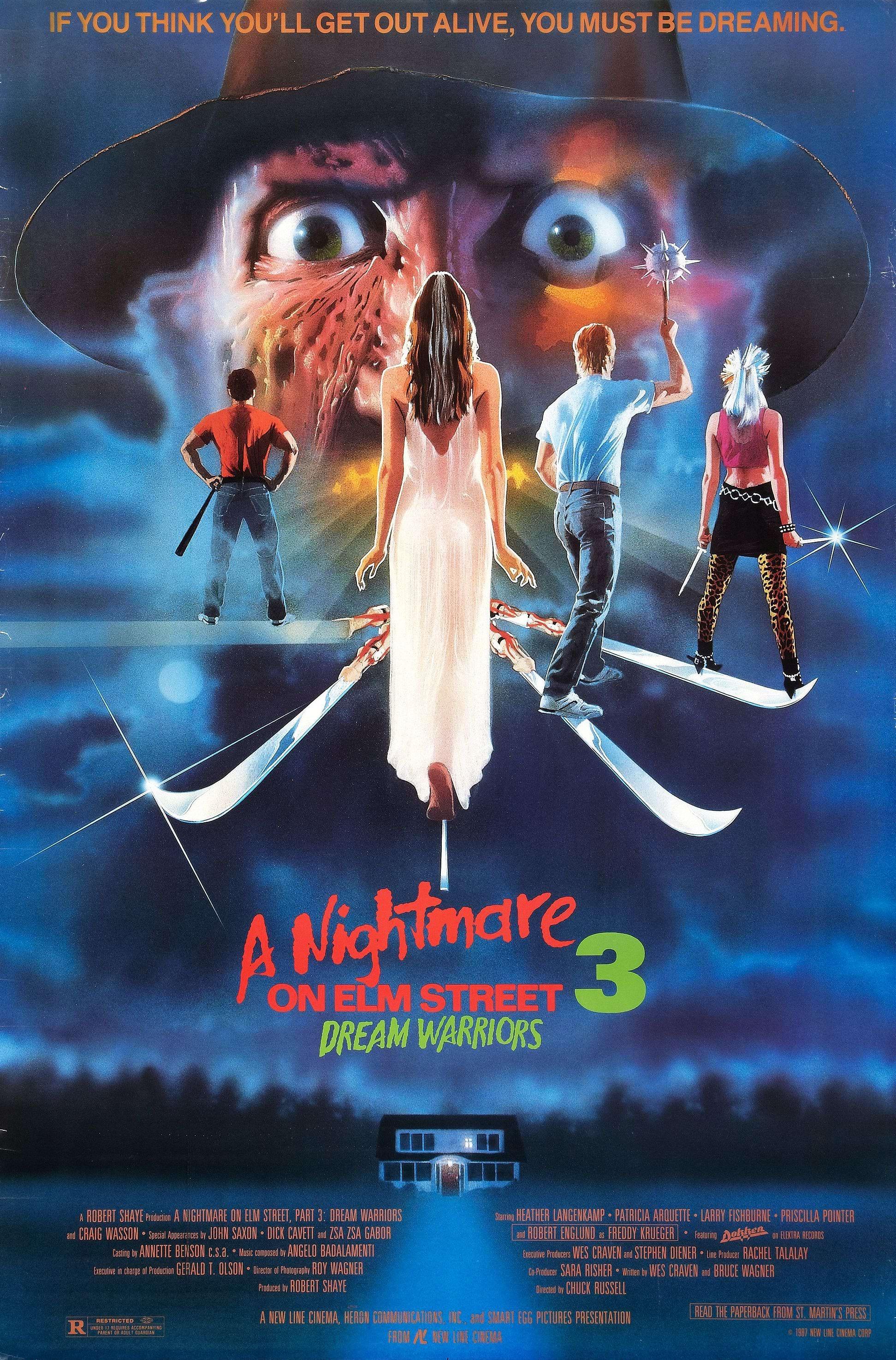

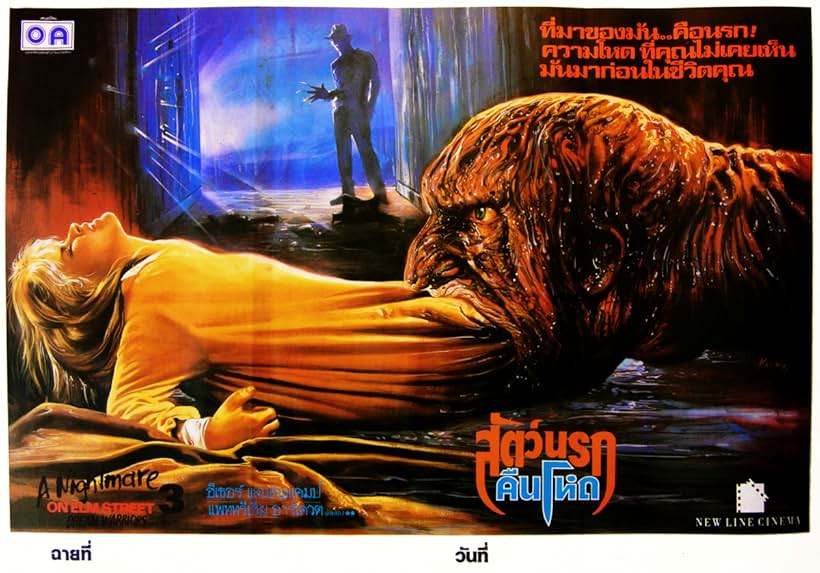

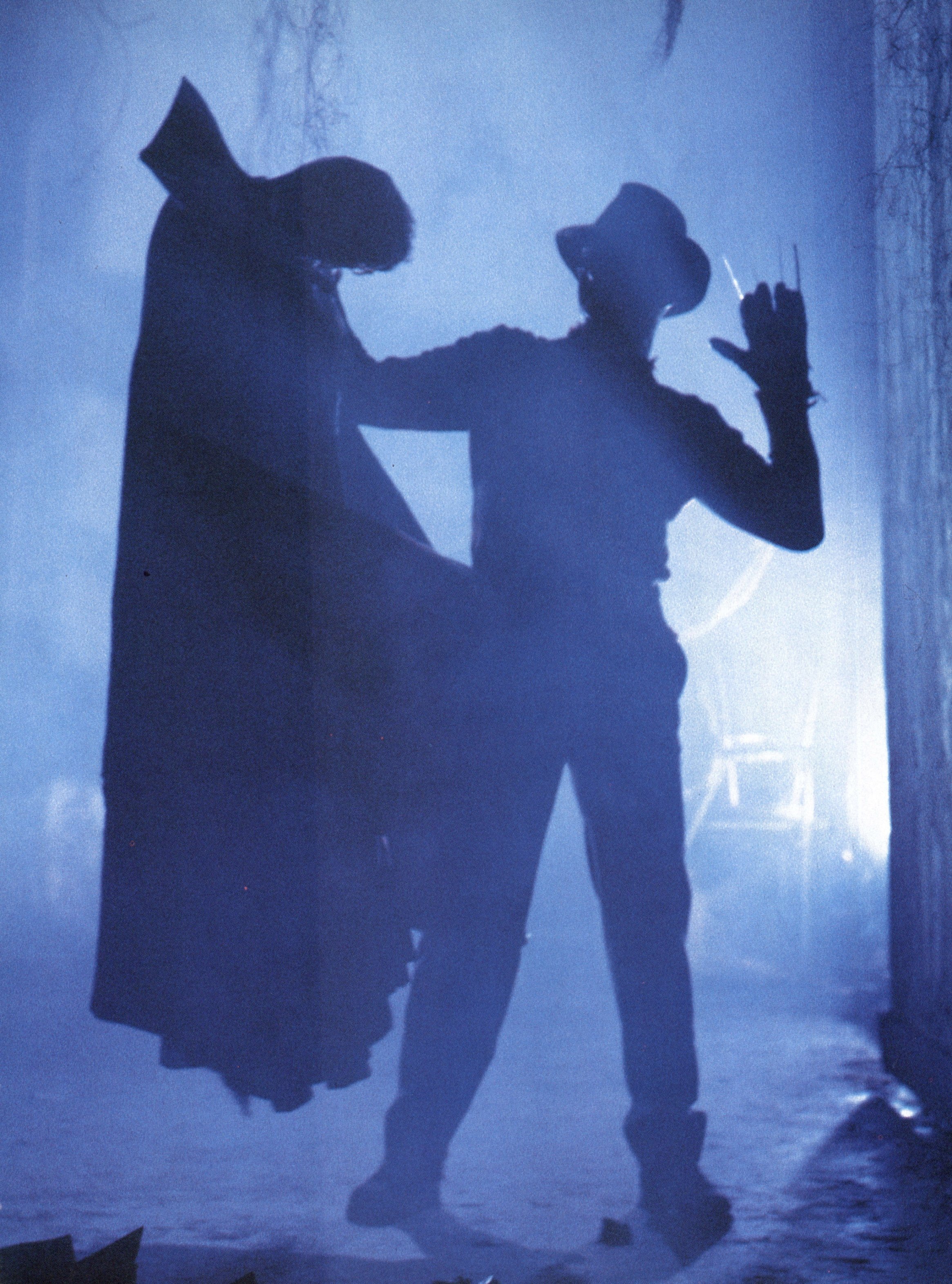

The Nightmare on Elm Street movies have, for better or worse, become a part of our collective movie going psyche, and a grand stylization of its unconscious. The original, directed by Wes Craven (The Hills Have Eyes, The Last House on the Left), is a small miracle of celluloid horror, deftly mixing its characters’ paranoid lives with the dreams they have — dreams which can kill them. Thus, was created Freddy Krueger, the series’ monstrous and quite witty villain. Freddy’s trademarks are an old hat tipped over his hideously disfigured face, an inhuman laugh, and claw-like hands with long razors for fingers. His arms can stretch out 10 to 20 feet in any direction to catch a victim. He makes his appearance in young people’s dreams, his favorite domain for menace, torture and echoing laughter.

Despite a very low budget, the first Elm Street movie looked glossy and inspired. It quickly racked up $24 million at the box office. A sequel was inevitable. Within a year, New Line Cinema released the second installment: Freddy's Revenge. Wes Craven had nothing to do with this one, and only Robert Englund (who, under thick makeup, plays Freddy) survived the original cast. Compared to the first one, A Nightmare on Elm Street: Part 2 looked bloated and clunky. And, yet, it still managed to do $30 million worth of business. With the Freddy Krueger persona now reaching cult stature, (posters, fan clubs, a rock song) the propagation of Elm Street movies became a pop culture natural, not to mention very good business.

A Nightmare On Elm Street, Part 3: Dream Warriors, heralds the return of Wes Craven, as co-writer and executive producer. New Line has put more money into this one (a little over $4.5 million), its first wide national release.

“There is a world that I see as a writer. The cinematographer is my transmitter to it.”

— writer-director Chuck Russell

The new movie brings back the original heroine (Heather Langencamp, then a troubled teen dreamer, now a specialist in dream disorders) and her cop father (John Saxon). Directing is Chuck Russell, an authority on dreams himself, having co-written the movie Dreamscape. Roy H. Wagner is the director of photography.

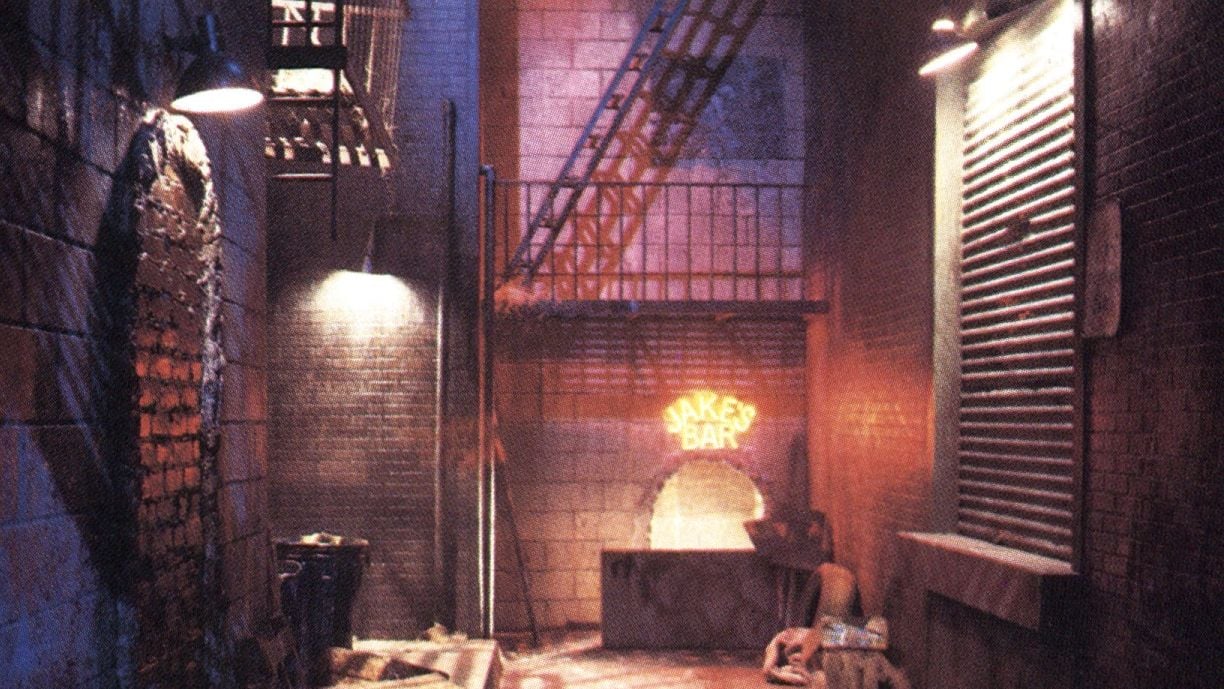

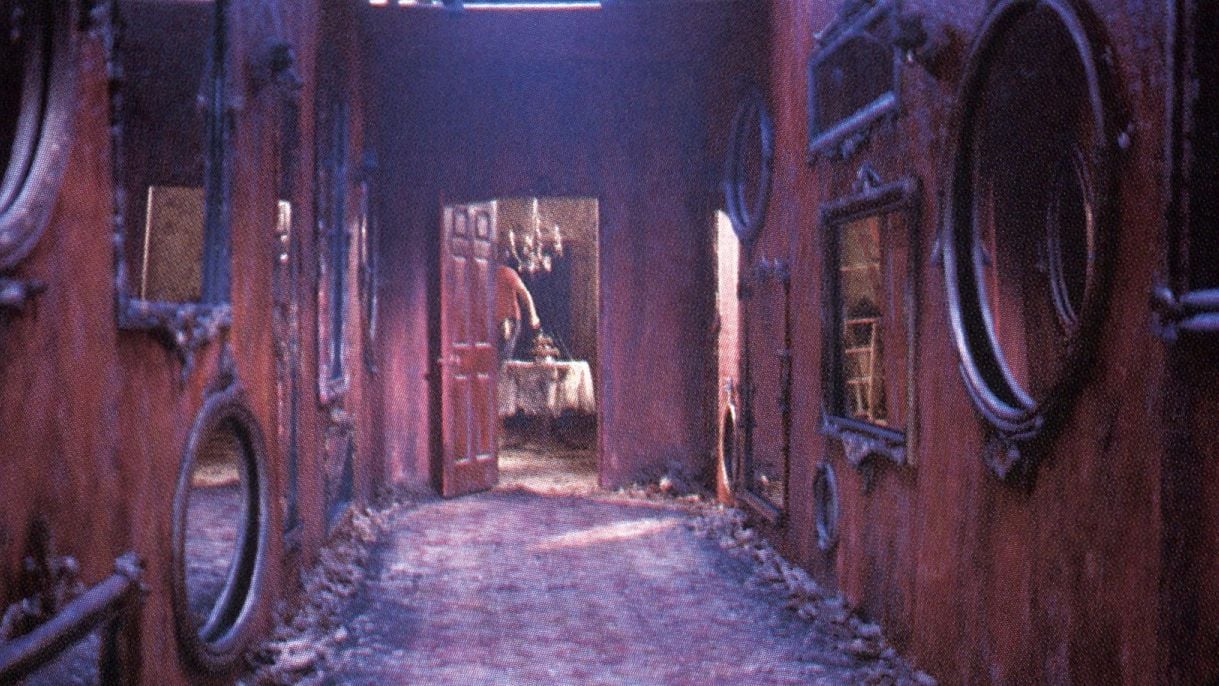

This was a very complicated project. It required recruiting a number of units to handle different areas of visual effects — optical, mechanical, smoke and steam, puppetry. In one section of the film, Freddy Kreuger turns into a snake. So, there was a unit working on rigging up the creature. A separate unit took up the task of creating tongues for the snake. A final battle in the film takes place in what the script describes as “Freddy Hell.’’ This is a large, dark, multi-leveled area, entered through cylinders, filled with big broken-down boilers and dripping pipes, charred walls, stagnant pools with skulls and bones and children’s toys floating in them. Freddy Hell took eight weeks to build. It was assembled, as were the film’s other 26 sets (among them, mental hospital wards, a nursery, a hall of mirrors, a bloodstained tunnel, a replica of the now rotting original house on Elm Street, a TV talk show studio) inside a 125,000-square-foot warehouse across from the Los Angeles County Jail.

Roy Wagner’s challenge in Elm Street 3 was a double whammy. It was a complicated shoot, and already a week behind schedule when he stepped in to replace the original cinematographer. He had no prep time. “I read the script one night and took it over the next day,” Wagner remembers. On his first day of work, he had to shoot the film’s finale, a fight in a junkyard between one of the good guys (Craig Wasson) and Freddy’s remains, buried in the back of a Cadillac and now come to life in the form of a skeleton. This entailed shooting against a bluescreen, with puppet skeleton effects and rear projection to follow.

“Coming into a project, a director doesn’t know what you can do,” says Wagner, whose previous credits include Beauty and the Beast, Witchboard, Pray for Death, Nine Deaths of the Ninja, Return to Horror High, and second unit work on Burglar (under William A. Fraker, ASC). “There is a world that I see as a writer,” says director Chuck Russell, “the cinematographer is my transmitter to it. Sometimes, it’s the same as I saw it; in some cases, it’s better. It’s that area between what’s in my imagination and what’s physically possible.”

Most difficult to realize on a project like this one, he says, are the dream transitions, those moments when reality and the doors to dreams blur. He calls the Elm Street films “rubber-reality movies, with Altered States at the top end, and House at the bottom end.”

The dream warriors of the title in Elm Street 3 are seven teenage patients seeking help for suicidal tendencies at a psychiatric hospital. Freddy enters their dreams and... well, drives them to kill themselves. One girl is blown up with syringes; a disabled young man is chased by his wheelchair, now three times its normal size and sprouting knives and razors; another girl is tormented by Freddy-as-a-snake, and swallowed up by him. It’s a regular parade of the grisly.

“The toughest thing for me was having to go between all the different units,” says Wagner. Various production units were going on at all times during the film’s eight-week shooting period inside the downtown L.A. warehouse. “They’d call me away from whatever I was shooting at the moment. Walking over to an old set we’d left two weeks ago, I had to clear my mind and try to refresh myself on what set I was returning to. Sequences could not be completed until effects were finished. We’d have to leave lights — up to 140 lights — hanging in place until we came back two weeks later.” An elaborate note-taking technique which Wagner employs on all his movies came particularly handy on this one. For each shot, he and his second camera assistant (Giles Dunning) would keep notes detailing the T-stop, the lens size, film stock, the foot candles for key/fill/and backlight, the type of filters used, if any, the height and distance of the camera, and, on the back of these notes, charts illustrating camera placement and movement.

“I shoot Freddy like I would a product shot. He is the product. You have to be very analytical about him, light him a certain way, very little front light, and no long-lasting close-ups. He’s got to have shadows, and shadow details.”

— cinematographer Roy H. Wagner

“It’s good management,” Wagner says, “and I think, sometimes, art has to be married to management.” Back when he started out as a cinematographer, he wanted to find out exactly how much time the camera crew spent on each shot. The usual complaints were heard around the set: “It’s too slow,” and “Why is it taking so long?”

“I wanted to see how fast I was. From the time we got the floor to the time we returned it, how much time was that? I timed it. I found that a new set-up took half an hour to an hour, and new locations, where we had to move trucks, took two hours. But, the average time it took for a shot was 3-10 minutes. So, most of the time was taken up by production — hair, makeup, discussions, effects.”

To say that Roy Wagner’s crew worked fast on this project would be to put it mildly. “On optical days, we averaged 14 setups. On regular days, 30 setups.” And, this was done under very dark and moody lighting, and almost always requiring multi-level dolly shots.

Most of Nightmare takes place under a veil of murky smoke. “The density is a constant problem,” Wagner says, “It’s not fun to breathe smoke. A lot of people say a cinematographer who uses smoke isn’t a good cinematographer. When you look at something in real life there’s atmospheric perspective; color that’s near you is very saturated; far from you it’s softer, more pastel. This is because of the dust in the air. When you turn the light on, it pierces through the dust particles and eliminates atmospheric perspective. With smoke, you recreate that perspective by bringing density back up to the atmosphere. You recreate a natural light quality. It also fills the shadows. We used a lot of bee smoke, which hangs in the air for a long time, and some dry ice, which tends to cling to the floor.”

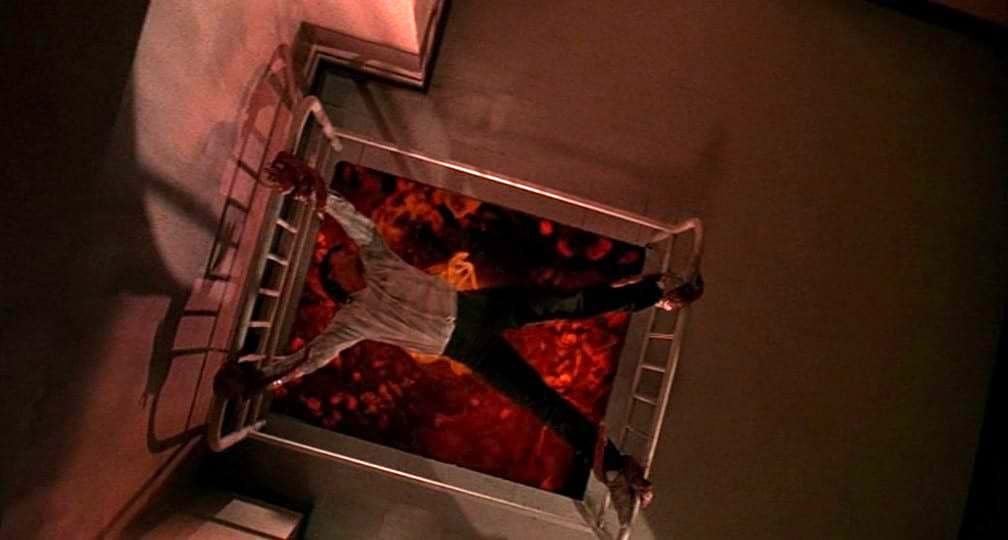

The only stylized color light in the film was used in Freddy Hell — red fire and flames which get cooler, whiter and bluer, as they get closer to the heart of the fire. “Horror films are hard,” says Wagner, chuckling, “because they are always at night with the lights off. Where is the light coming from? After a while, you long to do a film where someone comes into a room and turns a light on. Basically, I light night with a big moon bouncing light, a directional soft light. I tend to like bigger single light sources of illumination, which I can then diffuse or soften.

“I rate my exposure by evaluating the tones of all the elements in the scene, using a gray scale for the tones, from black to white. There are three important elements to consider: The characteristic curve of the film stock, the subject’s reflectivity, or how it responds to the light that falls on it, and, most important, choosing the right exposure for those elements and placing them on the straight line portion of the curve in a manner which will appear as you choose to make it appear in your mind. This is my modification of Ansel Adams Pre-visualization process.”

Wagner uses his eye as a reflected meter (“some people use a spot meter”), and evaluates his measurements by using an incident meter. “Harry Stradling Sr. [ASC] said that your eye is your best meter. But I want a technological confirmation. If you rely too much on the meter, you’ve eliminated part of the great wealth of enjoyment of those choices, and you take more time.”

Since a lot of Elm Street 3’s shots involved complicated dolly moves, it was essential that light sources be equally mobile. “I use a Panalite a lot, and I use it to be a soft fill. Sometimes a fill light will throw its own shadow, but a Panalite [which can be dimmed up or down] casts a shadow of the subject behind it [so it’s hidden]. You can carry it along on top of the camera.

“Unless the director doesn’t want to see the actor’s eyes — say, if he wants to veil what the actor is thinking — I think the Panalite is ideal. Film acting is in the eyes, and it puts a sparkle in them.”

He says he tries to “continue” a shot as long as possible so that a scene can maintain a greater sense of continuity and performance. The price of not cutting a scene up is paid for by having to do those complicated dolly moves. Wagner quotes another of his idols: “Gregg Toland said he’d compromise the photography any time to tell a story better. I want to tell stories with images.”

The temptation, when one embarks on a sequel, is to make it bigger, more exaggerated than the one before it. It’s a trap that Elm Street 2 clearly fell into. For one thing, the horror sequences became production numbers, instead of being plausible extensions of the story. For another thing, too much of Freddy Krueger’s face was shown.

“I shoot Freddy like I would a product shot,” Wagner explains. “He is the product. You have to be very analytical about him, light him a certain way, very little front light, and no long-lasting close-ups. He’s got to have shadows, and shadow details. When you see his face too much, it destroys the illusion. It’s important for an audience to recognize him. We tried shooting him with his hat off, for example, but it just didn’t work as well.”

Freddy’s specific lighting starts to pose problems as he moves within an environment. Then, lighting would have to be dimmed in the middle of the shot, or transitional lighting would have to occupy the spot where an actor leaves and Freddy comes in.

Almost all of Elm Street 3 takes place at night. Wagner used Mitchell diffusion filters to soften actors’ faces, coral filters to slightly infer a warmth, like a fire light glow, and super frost filters to open up the shadows.

Curiously enough, he used no 5294 Kodak film stock at all. “I strongly believe that when you go through the intermediate stages [to release prints], 5294 tends to lose its mid tones, its intermediate grays. I think the 5247 looks creamier than the 5294. I have found that you also lose mid tones in Agfa and Fuji. People like Fuji because of its pastels, but I think you can do that with Eastman, depending on how you expose the color. Eastman is best because it allows you a lot of possibilities. By stopping down, you can saturate. I like not to be limited by my stock. Kodak is also consistent from batch to batch. I’ve found it to be quieter going through the camera [due to its thicker base].”

Of the highest importance, he adds, is the fact that Kodak, as well as DeLuxe Labs (which processed Elm Street 3), support and understand the cinematographer.

One scene in the new Elm Street sequel reveals a girl sleeping in her bed. As the camera pulls away, the girl wakes up to find she’s in her bed in the middle of the street (Elm Street, of course), with children in white dancing in the yard behind her, in slow motion. “We shot her lying in bed at regular speed,” Wagner recounts. “As she lifts up to the headboard, the camera moves back and the speed goes up from 24 frames to 60 frames per second. The girl has turned around, so her back is to us. At this point we can’t see she’s in slow motion too. The children in the back of her are dancing and skipping in slow motion. She floats into dream state, and it’s eerie.” The speed/aperture control computer from Clairmont Camera changes the speed and the aperture at the same time.

He says he shot a lot of things in reverse, or with changing speeds, or flying walls. “Rather than print in reverse, you can shoot in reverse, and save a generation loss in the process. For a scene on a recent film of mine [Witchboard], where an ax misses hitting the actor by a few inches, we shot in reverse, so that the ax was taken out of the wall. In this way you could get it closer to the actor’s face, without endangering him. The actor had to learn how to react in shock in reverse, by looking at his expression on the Moviola.” Another freaky Scene in Elm Street 3, shows a girl in a hospital corridor, with an open door visible behind her. As the camera moves in close, normal (24 frames per second) speed changes to 8 frames per second (with exposure compensation), and the door in the corridor turns out to be the front door of the Elm Street house, which slams shut. As the camera whips back, the hospital walls fly, and the girl ends up trapped inside the house.

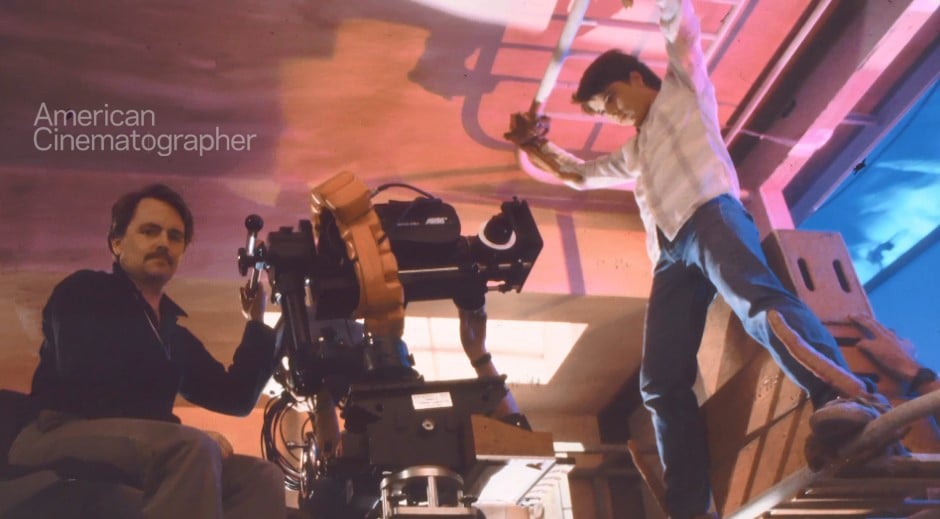

“Freddy Hell,” says Wagner, “was constructed in such a way that you could not put a camera anywhere easily. There were so many levels to it. I insisted on getting a Louma crane, and they kept saying, ‘No, no no.’ It has an ill-deserved reputation for slowing a company down. I used it as a floating tripod, for still and moving shots. It saved us. We did in three days what we had scheduled for five.” The snake sequence, on the other hand, which lasts all of 15 seconds on screen, took up three sets and a week and a half of shooting. The snake (built by special makeup effects artist Kevin Yagher, creator of Freddy’s makeup), with Freddy’s head on it, bursts through the floor, and swallows up one of its victims. In addition, four two-foot-long tongues get ejected from someone’s mouth to strap one of the characters to the posts of a bed. Then the tongues (their wiring rigged from under the set, by the puppeteer’s hand) writhe while strapped to a burning pit. “They look really frightening,” says Wagner, “and so real. Even on the set.”

Wagner photographed A Nightmare on Elm Street, Part 3, with an Arri BL 4, an Arri 3 and an Arri IIC (for second unit) and a Mitchell GC (for opticals). In addition to the Louma, he used a Chapman crane extensively, a Jonathan jib arm, and a Weaver-Steadman head. (“We always seemed to be on our knees,” he jokes.)

He describes the relationship between a director of photography and director as follows: “You’re dealing with the technology and the art of cinematography with people who need not know how you do it, yet expressing what the director has already seen. It’s a real partnership. I like the first time directors because they challenge you — they’re trying to express in a new way. Sometimes the best work is done under this oppression of budget and scheduling. If you give producers what they want — time and money — and the director what he needs, which is an expression of their thoughts, then you’ve done your job.

“I’m really interested in why people make the choices they make, more so than in whether I agree with their choices or not. It has to do with a world view, an interpretation. One thing Bill Fraker taught me was: ‘Put yourself at risk. In doing so you grow and have a greater potential of doing something worthwhile.”

A number of years ago, Wagner interviewed some of Hollywood’s best cinematographers for a documentary project co-produced by the American Society of Cinematographers and Thunderbird Productions (a company now defunct). He talked to George Folsey, Burnett Guffey, Joseph Ruttenburg, Bill Fraker, Bill Clothier, Stanley Cortez, Charles Lang, Joe Biroc, and others, about their philosophies and techniques. “In this country,” he says, “we’re style-conscious. A cinematographer’s history is important — to understand who taught him, his choices, why he made them, if he was taught that speed is everything. Truffaut said once, ‘A successful film for us is one that breaks even. And, when that happens, we break the champagne.’

“When people come out of film school, they have nowhere to go. There’s a whole procedural process, how director of photography responds to a director, to a grip, those relationships and the people who deal with them. A lot of cinematographers fail because they don’t know what’s expected, and although they are proficient, they’re not able to perform in a manner that’s expected.”

Ten years ago, while making a documentary in Australia, Wagner was struck by the enthusiasm and innocence of the technical crew he encountered there. He told them, “You remind me of us in the 1930s — you don’t know what you can’t do yet.”

Wagner was invited to join the ASC in 1988, and went on to shoot features including Another Stakeout, Drop Zone, Nick of Time and Stand!. He earned Emmy Awards for his camerawork in the series Quantum Leap and Beauty and the Beast, and also shot such shows as Party of Five, Houston Knights, Fantasy Island, Get Real, CSI: Crime Scene Investigation, Burn Notice, House, Elementary and Ray Donovan.

He was recently interviewed for the AC article “Terror Through Lighting” — focusing on his approach to shooting for horror films.

His memoir, Roy H. Wagner: A Cinematographer's Life Beyond the Shadows, will be released next year and details his more than 50 years of camerawork.