On Location with Jaws

Seeking realism for the filming of a bestseller about a killer great white shark, film crew works under enormous difficulties at sea off Martha’s Vineyard.

I had gone out to Martha’s Vineyard for a short vacation but when I heard that a feature film called Jaws was being shot I ended up spending most of my time watching the filming.

Jaws is an adaptation from the Peter Benchley bestseller, which was sold while still in galley form to producers Richard Zanuck and David Brown, who are making the picture for Universal. Peter Benchley is the son of the famous writer Robert Benchley.

Benchley got the idea for the story from a real incident that happened off of Montauk, Long Island, in 1964, when a 17-foot, 4,500-pound shark was caught by a fisherman named Frank Mundus.

During the shooting of Jaws, a story bearing the caption “Shark Scores KO” appeared in a Boston paper. A 1,500-to-2,000-pound shark grabbed an aluminum boat out on the swordfish grounds, 60 miles off Nantucket and violently shook it and the people in it.

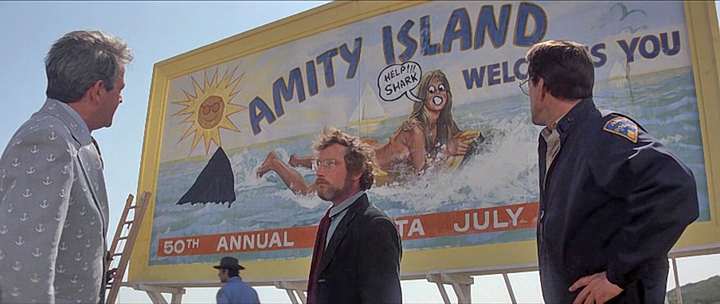

Simply sketched, the story is about a giant white shark that terrorizes a resort community called Amity, Long Island. Some people are killed by the shark and the town is dying because the shark is scaring away all the tourist business. Three men become involved in destroying the shark: Brody, Amity’s Chief of Police, who wears glasses and feels inadequate to deal with the shark; Hooper, a young shark expert from the Institute at Woods Hole; and Quint, the shark-boat captain who is hired by Brody to kill the shark. It’s kind of a modern-day Moby Dick. Although the basic idea is intact, there have been several major changes from book to screenplay. For example, in the book there is an affair between Hooper and Brody’s wife, which does not appear in the screenplay.

Edgartown on Martha’s Vineyard, the island off the coast of Cape Cod, was chosen to portray Amityville by the film’s designer, Joe Aves, after he visited scores of towns up and down the Eastern Seaboard. The site had to have an old, quiet, resort-town flavor, and because Edgartown is on an island, accessible only by ferry or plane, he has managed to maintain a style that is rapidly being lost to Cape Cod and Long Island. But the most important consideration was the suitability of the water locations, since more than half of the picture takes place on the water. The platform which operates the mechanical shark had to be placed in no less than 20 and no more than 30 feet of water. Also, a location with a small tide was needed because a large tide would swamp the shark and cause matching problems. Edgartown’s harbor had only a three-foot tide.

The cast for the movie consists of Richard Dreyfuss, star of The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz and American Graffiti, as Hooper; Roy Scheider, who co-starred with Gene Hackman in the The French Connection, as Brody; and Robert Shaw of The Sting, as Quint. Three very different and very exciting actors.

The film is being directed by Steve Spielberg who directed Goldie Hawn in Sugarland Express. When I first interviewed Steve, who is 26, I had a list of questions to ask him. My first was, “What is the most boring question an interviewer had ever asked you?” He said people always ask how he made it big in the film business so young. I decided to skip my second, but from many other interviews I know that Steve made a short called Amblin’ for $15,000 while still in school. The film was 20 minutes long. When it was completed, he showed it to a producer who liked it and he got his start directing television. Sugarland Express was his first feature. When I asked Steve why he wanted to direct Jaws he responded, “I knew my mechanical mind would be good with the mechanical shark.”

“Everything is actually being shot right on and in the sea. We’re not going to a tank, a back lot, miniaturization, etc.”

— Steven Spielberg

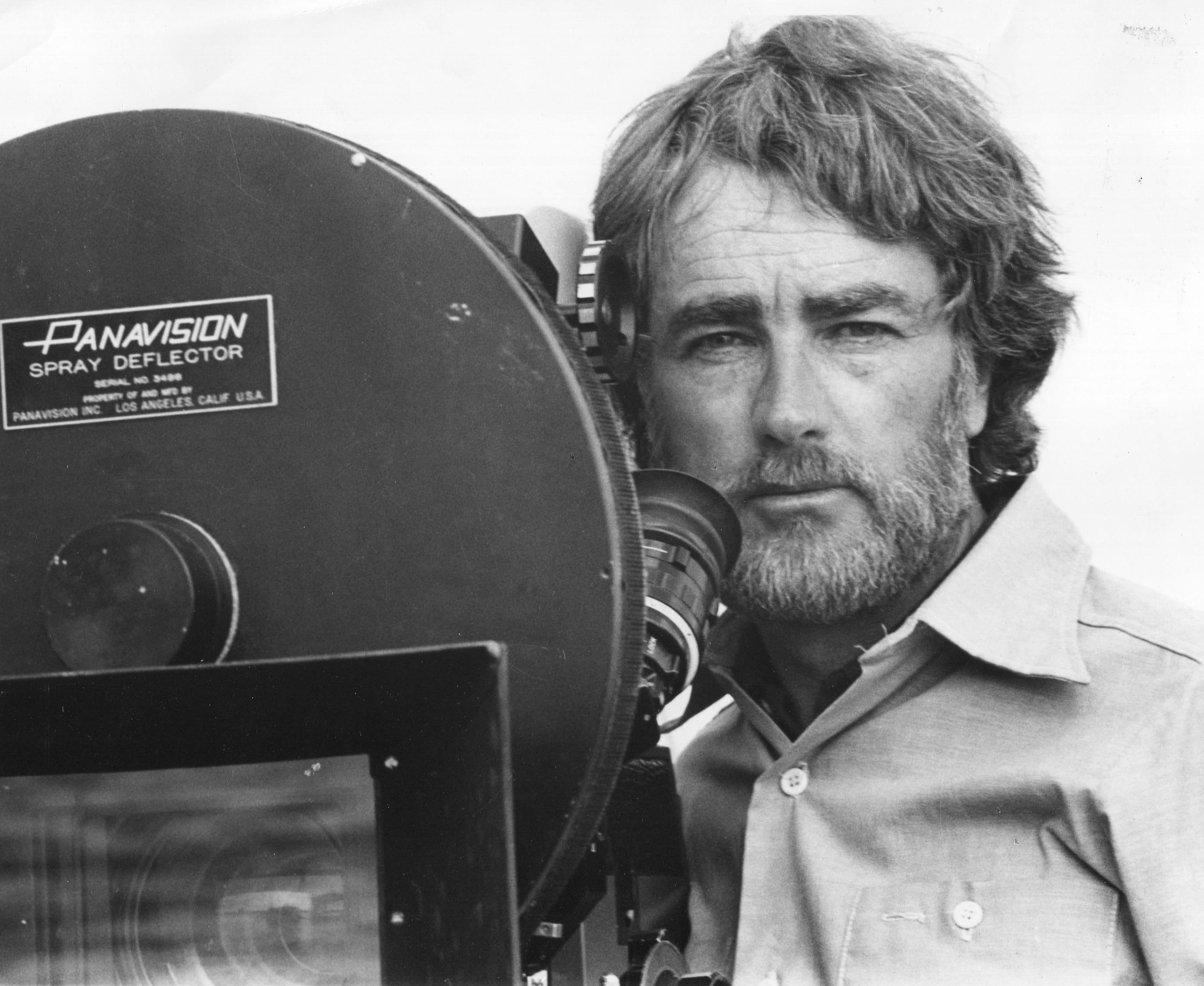

The director of photography on the film is William Butler. His operator is Michael Chapman, who photographed The White Dawn, and his assistant is Jim Contner.

Butler started out in the business making documentaries with William Friedkin. He worked in television for many years in Chicago before switching to film and moving to Los Angeles. The rest of the camera crew, which at times had three cameras running at once, was from New York. Butler’s last picture was The Conversation for Francis Ford Coppola. I asked Bill how he thought the picture should look. “My philosophy for this film was that it should have an Andrew Wyeth look in the beginning, and as the story takes place around the Fourth of July I wanted it to look sunshiny. For the third act at sea, when they go for the shark, my feeling was that it should be dreary. It should look ominous, and foreboding. Having no control over New England weather was a problem, but by careful choice of angle I think we can make everything match, even though the weather was often against us.”

Bill is a student of painting but also emphasizes the cameraman’s reliance on mechanical aptitude. “A big part of what I do”, he says, “doesn’t have to do with shooting at all. It has to do with handling people. Knowing what gaffer or which grip is right to handle a certain problem.”

Shooting on the water posed many special problems for Spielberg and Butler. As Spielberg said, “I can’t think of any film about the sea that is technically as difficult as this one. Everything is actually being shot right on and in the sea. We’re not going to a tank, a back lot, miniaturization, etc.”

Drifting is a big problem. The crew may spend several hours setting up a shot only to find that the boats have drifted out of position. Curious boaters attracted by the action and the machinery also proved a big problem and several small boats had to be on traffic patrol at all times when the company was shooting near land.

The Martha’s Vineyard shooting was originally set to be completed in June before the start of the summer season when the Island swells from a population of 6,000 to its summer population of more than 40,000 — but when the summer people had gone the Jaws crew was still shooting.

“Morally, I can account for only one-fourth of a day’s work done every day,” says Spielberg, “and 70 percent of the problem has been the water. This is the first picture to do half of its shooting on location at sea. Because it’s the first, it’s bloody expensive. This picture is a mathematician’s dream and a filmmaker’s horror.”

Spielberg also attributes part of his problems to “a very enthusiastic director and art director [Joe Alves]. We have been unwilling to compromise. It gets costly but it makes good movies.” Another problem which Spielberg didn’t discuss was the speed with which the project happened. A lot of thought was given to the feasibility of the project, but once the go-ahead was given things happened very fast. Probably more time experimenting and preparing during the pre-production period would have helped, but because of the schedule the time was scarce. All experimentation was done on first unit time. Spielberg would often shoot what normally would have been a rehearsal just to be safe, especially those shots involving special effects.

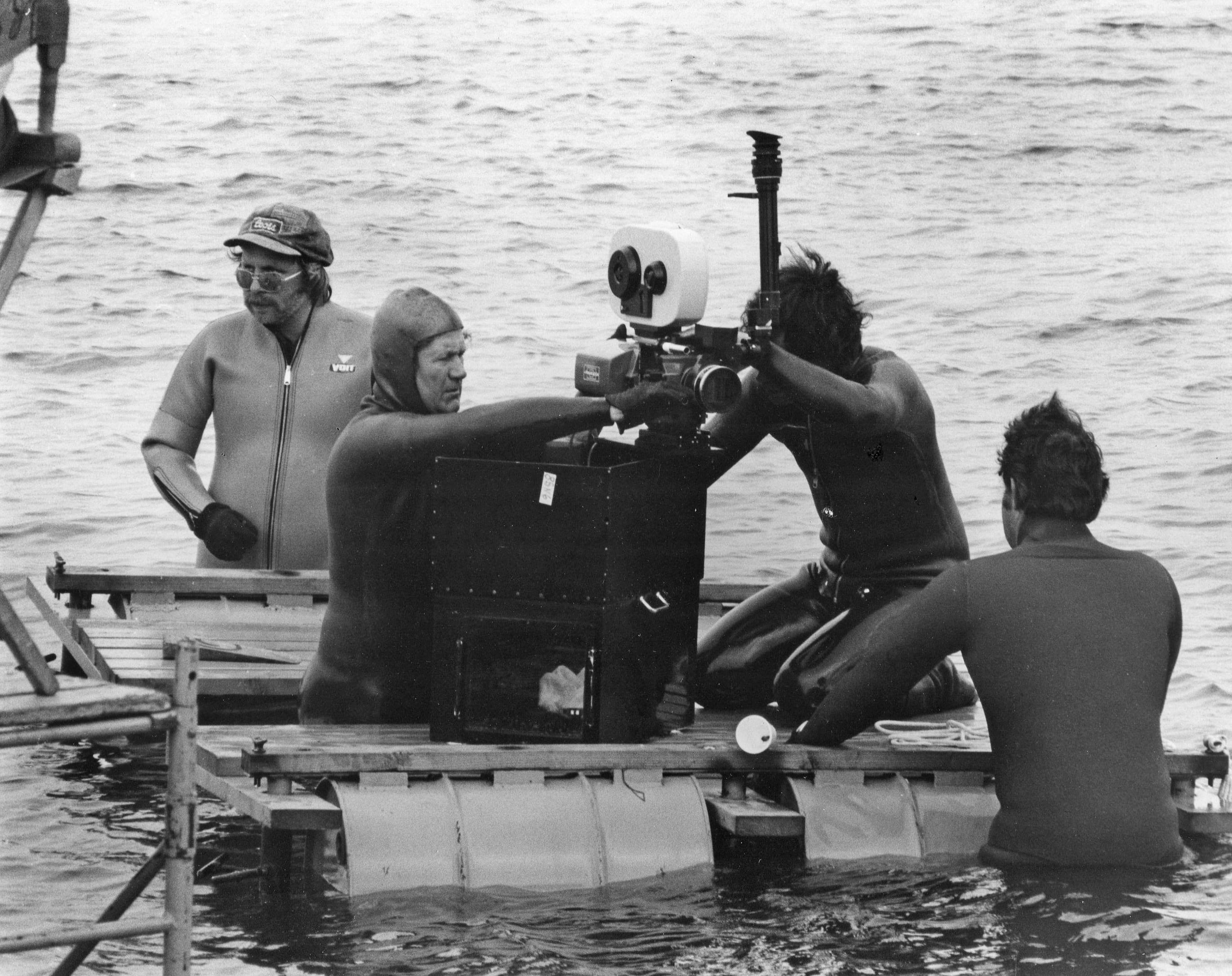

Spielberg considers Jaws to be “probably the most expensive handheld movie ever made.” Because of the movement on the boat caused by the waves, Butler and his operator, Mike Chapman, found they could get a steadier shot by hand-holding the Panaflex camera for many situations. I asked Chapman how he liked working with the Panaflex camera: “At first I was worried about the viewing system. The eyepiece is up against the camera and it took me a while to get used to that. As a hand-held camera, it’s rather heavy, 34 pounds, but it’s balanced very well. We really wouldn’t have been able to do this picture without the Panaflex. It’s not as big as the PSR and we had to do sound shots where we just couldn’t bring the PSR and go jumping from boat to boat eight and nine times a day.”

One of the interesting pieces of equipment that Butler developed for this marine movie was a special raft that could be raised or lowered (on its pontoons) out of the water to different levels. It also had a section cut out on one side that would fit the water box that was used to protect the Panaflex camera during shots that were done right on or in the water.

shown here was developed by Butler specially for this film. It could be raised or lowered (on Its pontoons) out

of the water to different levels.

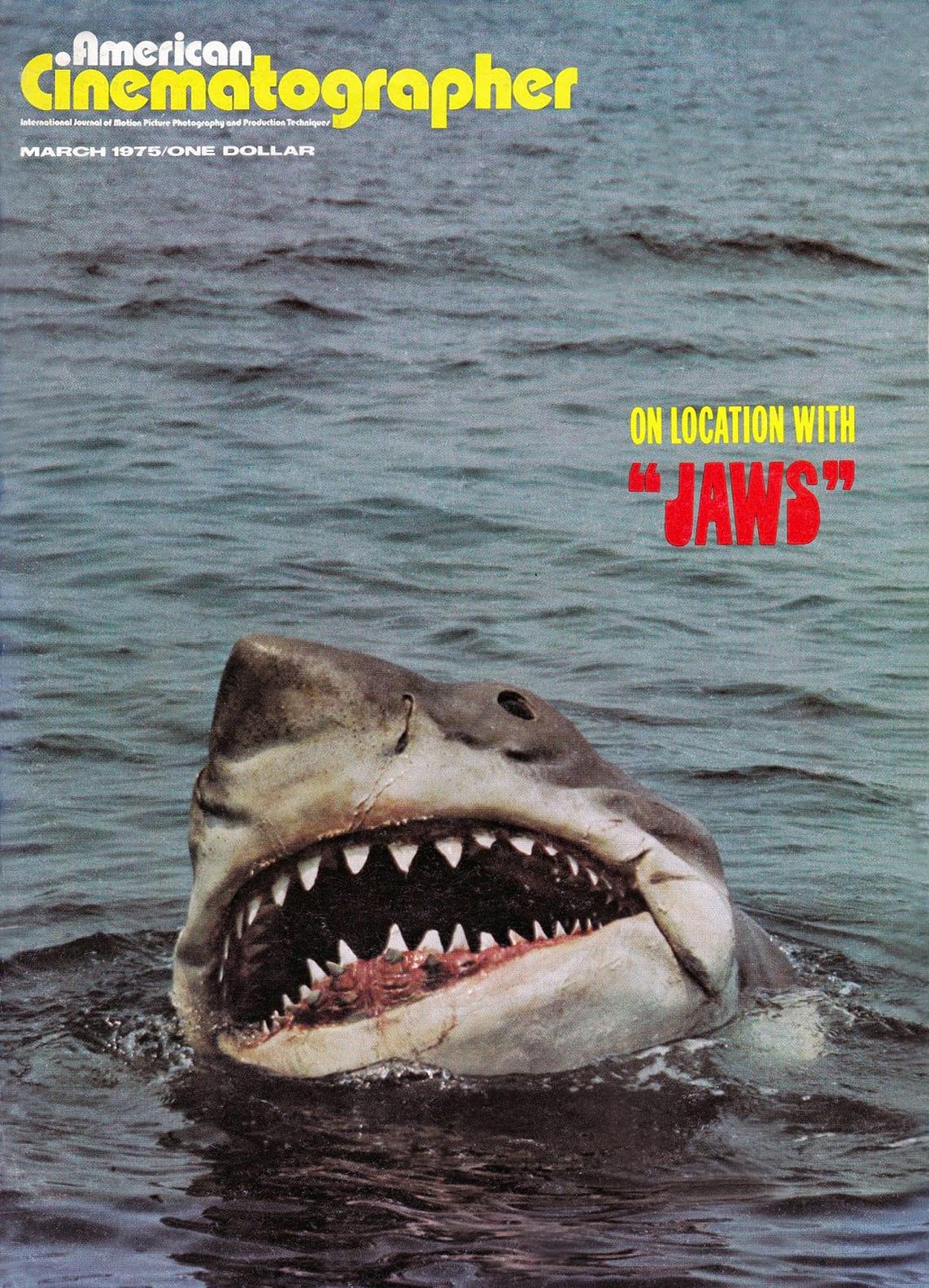

After the director, the second person to join this project was Joe Alves, the production designer. The most difficult part of Joe’s job was, of course, creating the shark. The producers had to be sure a realistic shark that would fill all the requirements of the script could be built before they could commit big money to the project. A shark was needed that was 25 feet long, that could jump out of the water and smash a boat, and eat people. To help build the shark, Alves hired Bob Mattey, for years head special effects man at Walt Disney. Bob created the giant squid for 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, but both he and Alves agree that this was the toughest assignment either one of them has ever had.

The shark cost $250,000 to build and twice that to operate. To start, Joe did a great deal of research on sharks at the Scripps Institute and the California Academy of Science. Not a great deal is known about great white sharks because they can live only a few hours in captivity. To help him with research, Joe found Leonard Campango, a young ichthyologist with a vast knowledge of sharks. Joe then started making small clay models, then full-scale drawings. When he had the drawings he was ready to make the full-scale clay model with a plywood armature that was to serve as a mold for the plastic body of the fish.

Actually, three sharks were made: a right-hand shark that had machinery exposed on its left side, a left-hand shark that was open on the right side, and a full shark that was also called the sled shark or the floater. The third shark was the one that was pulled behind a boat for certain shots. The other two work with a platform that is sunk to the bottom and has an arm, or powered gimbel, that moves back and forth to activate the shark.

Bob Mattey tried to explain to me how it all worked with hydraulics, pneumatics, and electronics, but it was all beyond me. I can tell you that the movements looked real. The skin for the shark was made from Lasmer, a liquid plastic. The shark had two sets of teeth — a hard set and a soft set, the latter designed to go easy on stuntmen. The skin was painted with silica sand to give it a sandpaper sharkskin texture so that the water would bead and run off it realistically.

“Bruce,” as the mechanical monster is known to the crew, is stored and repaired in “Shark City,” a 200'x75' shed where over a score of special effects men wait in attendance to this sea king. When Bruce, during a difficult dive, rammed into his platform, the production was delayed for a week while Bruce got a nose job. The salt water corrodes everything metal, including Bruce’s internals, and his skin gets sun bleached, so every week he gets a new skin. Inside the mechanical star is a mass of nuts and bolts. The backbone is made out of yellow tubular and spring steel. About 500' of plastic tubing, 25 remote-controlled valves and 20 electric and pneumatic hoses provide the power.

The second big design problem for Joe Alves was the boat which is the set for the whole last third of the picture. “For Quint’s boat, the Orca”, explains Joe Alves, “we bought a Nova Scotia boat and totally redid it, because we wanted Quint’s boat to have a special character.”

Actually, there were two boats, the Orca I and the Orca II. The Orca II was a special effects boat designed to smash and sink when attacked by the shark. Made from fiberglass using the Orca I as a model, it resembled it in every superficial detail. The Orca II had no bottom, just a steel scaffold to which several barrels were attached. The barrels could be filled with water to sink the boat and then filled with compressed air to raise it again. The boat was built in levels so it could be dismantled and fitted into its storage shed. The engine hatch was made of balsa so it would splinter when the engine exploded. Three transoms were also made of balsa so they would break away when the shark crashes down on the end of the boat in the climax of the story.

Besides the robot there are some real sharks in the picture. A 13' tiger shark was flown up from Florida for use in a scene in the picture where the townspeople in the picture think they’ve captured their killer. A lot of real shark footage was shot for the film by Ron and Valerie Taylor, two Australian shark experts who were responsible for the film Blue Water, White Death, which was a big box office success a while ago.

The timing of my visit to the set of Jaws was quite fortunate. My first trip out to the many boats and barges that made up the set was on the day when they were shooting the most important scene in the picture, the one in which the shark leaps out of the water and crashes down on the back of the boat. The whole afternoon was spent in preparing the shot and as it approached 5:30 PM, the end of the day, it looked like they were never going to get the shot off, but just before 5:30 everything came together and Steve Spielberg decided to go for the shot. He called, “Action” and he got a lot more than he called for. Steve, Roy Scheider, Dick Butler (Robert Shaw’s stuntman and no relation to Bill), Bill Butler, three camera crews and three cameras were all aboard the Orca II. When the shark came down on the boat, it looked like an explosion and for 30 seconds all hell broke loose. The weight of the shark caused the boat to fill up with too much water and it started to go down like a stone. I saw Roy Scheider dive into a mass of nail-filled pieces of wood splintered from the transom by the shark and did not see him come up for a long time. Other people were jumping clear of the boat and people on other boats were rushing to help them. There was much confusion and people were shouting, “Save the camera!” and “Save the lights!”

As the boat started to sink it also started to tip over. Some crew members on the work boat, The Ruddy Duck, also dove clear of their boat when they saw the 30' mast of the Orca II coming down on them like a tall timber. Fortunately, the Orca II was attached to a crane on one of the boats, The Whitefoot, and this kept the Orca II from sinking or tilting too much. To top it off, a sudden squall came up and it started to storm. After it was all over no one was seriously hurt but the number one camera had been submerged and the magazine with the hard-earned footage was filled with water.

Everyone thought the footage was lost and the whole thing would have to be done again, but Bill Butler had the magazine immediately taken to shore in a bucket of saltwater. Fresh water was then exchanged for the brine and the magazine was carried in someone’s lap on the next plane to New York to be processed that night at Technicolor in New York under the supervision of Otto Paoloni. They got the results the next morning. The footage was fine. No second take was made, and that is the footage that the public will see in the finished film.

You'll find more photos from the production of Jaws in this gallery.

Butler was honored at the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award in 2003 for his expert and inspiring camerawork in Jaws as well as his other films, including The Conversation, Capricorn One, Grease, Stripes and Rocky II, III and IV. He passed away in 2023.

Camera operator Michael Chapman later became an exceptional cinematographer himself and also an ASC member, shooting such pictures as Taxi Driver, Raging Bull and The Fugitive. He was honored with the ASC Lifetime Achievement Award in 2004. He passed away in 2020.

Camera assistant James A. Contner — son of J. Burgi Contner, ASC — would serve as the director of photography on the sequel Jaws 3-D (1983). He would also become a successful director, on such shows as Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Star Trek: Enterprise and Angel.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.