“Perfect” Images Earn Accolades

Cinematographer Jeff Cronenweth and director Mark Romanek devise intoxicating visuals for this Nine Inch Nails music video.

This article was originally published in AC July, 1997.

Cinematographer Jeff Cronenweth was honored for his work on the Nine Inch Nails video “The Perfect Drug” at the sixth annual Music Video Production Awards (MVPA), held on May 1 at the El Rey Theater in Los Angeles. The other nominees for Best Cinematography were Carolyn Chen (Luscious Jackson, “Naked Eye”), Tim Ives (The Wallflowers, “One Headlight”), Jo Molitoris (Live, “Lakini’s Juice”) and Troy Smith (Erykah Badu, “On & On”). The NIN clip also received awards for director Mark Romanek and hair/makeup artists Cemal and Joanne Gair.

Cronenweth gained invaluable experience while assisting his father — Jordan Cronenweth, ASC — on such features as Peggy Sue Got Married, Gardens of Stone and Final Analysis, and on many commercial and music video projects. He remarks about the award, “I was so busy working that I didn’t even know who was nominated until the week before the event. It was a great surprise, but the video winning had to do with a lot of elements coming together, including the art direction, costuming, and, of course, the direction. Mark is such an extremely bright fellow that it’s hard to go wrong.”

He recalls, “I first met Mark Romanek on the set of a Michael Jackson video that my father shot for David Fincher. A few years later, just as I was getting my first opportunities to shoot, I operated a few times for Harris Savides. One of those jobs was on another Jackson video, ‘Scream,’ which Mark directed, so we met again. Harris then got busy shooting The Game for Fincher. After seeing some of my other work, Mark called me in to do some videos.”

Cronenweth and Romanek subsequently collaborated on clips for the alternative rock bands Eels and Weezer. The duo then tackled NIN’s “The Perfect Drug,” a cut from the Lost Highway soundtrack disc. The director had previously helmed a disturbing video for the NIN tune “Closer,” with camerawork by Savides which was influenced by the images of still photographer Joel-Peter Witkin.

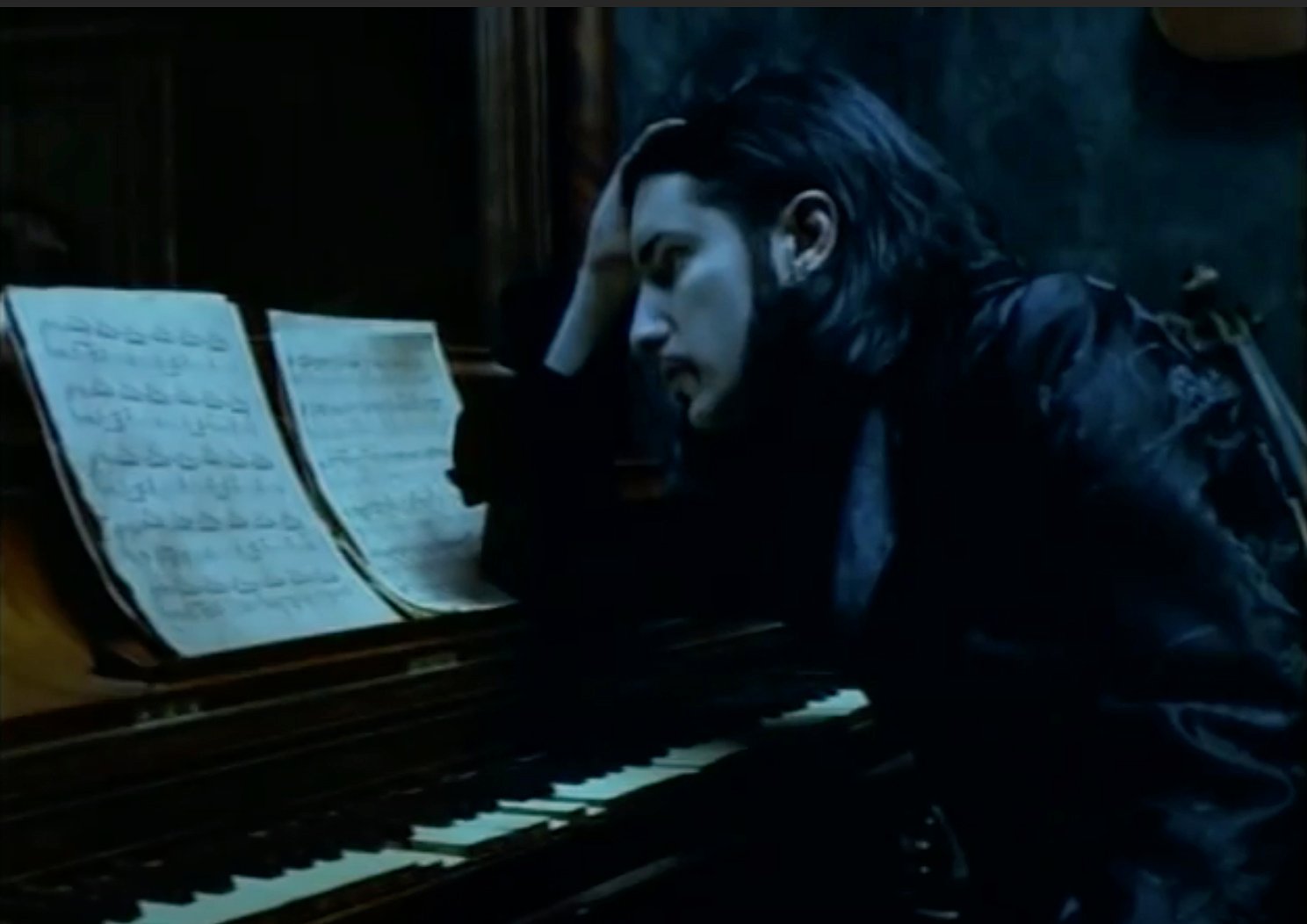

With lyrics expressing the yearning for an addictive love, “The Perfect Drug” video opens with melancholy frontman Trent Reznor and his band performing mechanically in a distressed Victorian salon drenched in gloomy blue hues. Abandoning their instruments, they appear in a succession of carefully choreographed and composed shots set in a Gothic theatrical world of painted skies and oversized props. Backing vocals are delivered by a pair of women, one of whom offers Reznor a bottle of lustrous liquid on a silver tray. Enraged, he produces a dagger forged of ice and advances threateningly — his breath producing clouds of vapor as the ambiance suddenly becomes even colder. Reznor is then seen ceremonially pouring the liquid — revealed to be absinthe — which glows bright green in a glass goblet. After drinking, he is seated in an electrified chair which erupts with white arcs to form a halo around his head. As the drug takes effect, the room explodes in verdant, lightning-like flashes — ultimately returning Reznor to the indigo world where we first found him, albeit now deeper in despair.

Says Cronenweth of the video’s hauntingly baroque style, “Mark is really big on doing image research and using references, so we first studied a series of work done by still photographers in the 1940s and ’50s. The video was always going to be very dark and moody — although, as it turned out, it isn’t as dark as most of our references were. We were both probably a bit more conservative on the set, but of course that could have been altered later during the transfer.

“Our lighting plan is easy to explain in that we wanted everything to be completely artificial and unmotivated. Practicals were practicals, but our setting was very unrealistic. For every setup in each vignette, we needed to create three lighting scenarios: something from the top, something from the front, and then the green lightning effects. It was a long process, because the re-lighting took a lot of time.”

Cronenweth had one lighting day to prepare for the following four shoot days, but Romanek’s terse directorial style also helped keep the production on track. While kinetic and arresting, the video makes minimal use of camera movement. As the cinematographer explains, “The only time the camera moves is in a Steadicam shot that pulls back through an ivy hedge as Trent comes forward. Every other shot is locked off, and that’s something Mark often does. He likes things to be clean, level and symmetrical, which allows the image to be the most important thing since there isn’t any distracting or unnecessary movement. Tom Faden, our production designer, added a lot to that approach; the sets were really beautiful and interesting to shoot.”

“The Perfect Drug” was shot with Panavision cameras and Primo prime lenses on Kodak’s 5277 Vision 320T stock. “In hindsight, I would have used the [500T] 5279, because it gives you more [range in the exposure],” he says. “But I had recently done some second-unit work with Harris Savides for David Fincher on The Game, and we’d used quite a bit of the 320T, so I shot some tests and it looked really good.” A consistently shallow depth of field was achieved by shooting at a stop of T2 to 2.3.

Adding to the clip’s overall surrealistic effect was the strange metallicpatina fleshtones of the video’s performers. “That was a combination of lighting and makeup,” Cronenweth reveals. “Joanne Gair did a fantastic job with the makeup, which reflected a lot of light. Mark had done some visual tests with that effect when we were doing the pre-light. We were using a lot of daylight Kino Flos with full CTB [for the opening and end sequences]. Refracting off the skin, that really brought out a morbid color. A bit more blue was added in the [telecine] transfer, but it was predominately there in the photography.”

Subtle yet effective lighting enhances the sequence in which Reznor attacks with the ice knife. The scene itself was shot in a specially-built refrigerated room constructed on the production’s main stage. “Our freezing units added a lot of humidity to the room, which resulted in a really good [steaming] breath effect,” notes Cronenweth. “It was difficult to get a lot of backlight and crosslight on the breath to make it stand out, especially without also lighting his face, as he was moving so much. We tried to keep Trent very contrasty and side-lit in that shot. We ended up using multiple operated lamps, focusable ellipsoidals like [ETC’s] Source Fours, which produce a very sharp beam. We also used them to backlight the ice dagger Trent was holding.

“You also have to keep in mind that we couldn’t generate any heat in this room. It didn’t take a lot to change the atmosphere in there, which ruined the breath effect. A lot of our lighting — from above and the side — came from outside the [refrigerated] set, which was built with translucent walls made of a hard plastic sheeting.

“It took many, many passes to get those shots right, and it takes an enormous amount of effort to breathe in a way that produces those clouds of vapor, especially while singing. Trent could only do one sentence at a time, and we went through the whole song, which was very difficult for him.”

Clever backlighting again came into play for a shot of the glistening bottle of liquid being offered on a silver tray. As Cronenweth recalls, “Because the woman holding the tray was predominately top-lit and covered so much ground while walking forward toward the camera, it was impossible to keep a light behind the bottle. Instead, we glued mirrors behind it, which reflected the toplight and illuminated the liquid inside. That was a last-minute save we thought of on the set.” Standard backlighting illuminated Reznor’s emerald absinthe cocktail.

The electrical chair upon which Reznor sits was a prop built for the production, but its arcing discharges were merely an illusion. “The only way to do the effect for real is with Tesla coils,” explains Cronenweth, “which could have been used if we had done two camera passes — one with Trent and another for the arcs — and combined them. To save time and money, we instead built a ring of interactive lights — using refrigeratortype bulbs, a dimmer board and relays — into the prop around where his head would be. The arcs themselves were added in post and timed to the firing of the lights.”

Stroboscopic effects for the green-tinted “trip” sequence were realized with Lightning Strikes units. “We usually had five on each setup,” the cinematographer says, “each of them gelled with about six layers of full plus green. And while that did dampen the effect of the lights, it wasn’t as much as you’d think. They’re very powerful, and the sets were small. We also had to have the units very close to our subjects so we didn’t have all kinds of strange shadows. We’d just set them up one by one, and adjust the densities of the flashes, sometimes by using black silks”

Asked for his opinion of the completed “Perfect Drug” clip, the cinematographer enthusiastically offers, “It’s very dynamic, and it was also a terrific song. After four 18-hour days, it gets a bit trying to hear the same song over again, but watching Trent perform was very exciting. Each take was a full rendition with a lot of energy, which really makes a difference.”

At press time, Cronenweth and Romanek had just finished a new video for The Black Crows.

Cronenweth made his feature debut as a director of photography with Fight Club (1999), directed by Fincher, later shooting Romanek’s feature directorial debut, One Hour Photo (2002). Cronenweth’s other features include Down With Love, The Social Network, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, Gone Girl and A Million Little Pieces.

Among many other projects together, Cronenweth and Romanek would re-team to shoot the pilot for the recent sci-fi series Tales From the Loop.

Cronenweth was later invited to become a member of the ASC.

A large version of the composite image at the top of this page can be found here.