Large-Format Memories: Brainstorm

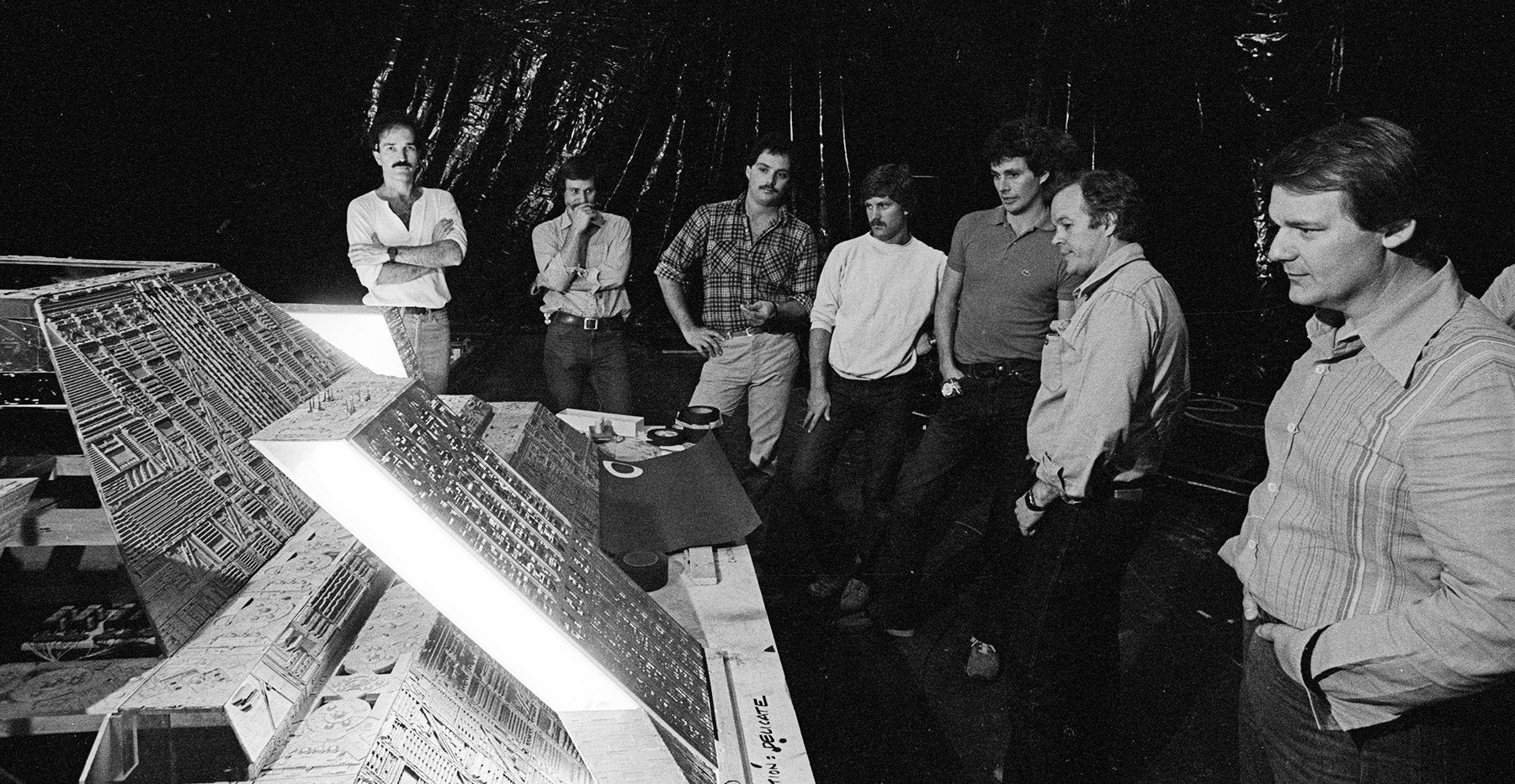

Richard Yuricich, ASC unlocked the potential of mixing 65mm and 35mm for Douglas Trumbull’s science-fiction classic.

The name Douglas Trumbull conjures certain enduring images in the minds of movie buffs: the pyschedelic Star Gate sequence from 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), the abstract stellar landscapes of Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979), and the futuristic nighttime canyons of Los Angeles in Blade Runner (1982). As a visual effects artist, his thinking went further and deeper than the screen. “He believed in experimentation and exploring new ideas to see what roads they would lead him down,” says Richard Yuricich, ASC, a visual effects cinematographer and business partner at Trumbull’s Entertainment Effects Group.

Despite his gift for visual storytelling, Trumbull had just two opportunities to direct his own work at the feature level: Silent Running (1972, photographed by Charles F. Wheeler, ASC) and Brainstorm (1983). Silent Running was filmed and distributed in 35mm (and on some 70mm prints), but by the time Trumbull began work on Brainstorm, he was thinking bigger, particularly where the film format was concerned. According to Yuricich, 8-perf VistaVision was a common format for high-end visual effects work in the 1970s and ’80s, but Trumbull saw that 65mm film offered a substantial advantage in resolution when compositing optical effects. He was also interested in the potential for the superior projection quality of 70mm, and with support from Paramount Pictures, began experimenting with higher framerates as a method of enhancing a film’s immersive qualities. This experimental process became known as Showscan.

In Brainstorm, Natalie Wood, Christopher Walken, and Louise Fletcher play research engineers working on a new technology that will revolutionize the field of communications: a brain-to-computer interface that allows the transmission and recording of thoughts and feelings, and even allows the user to control computers with their mind. The premise seemed to Trumbull a perfect opportunity to demonstrate Showscan’s potential, and he asked Yuricich to handle the film’s principal photography.

AC caught up with Yuricich to revisit his work on Brainstorm ahead of its 70mm repertory screenings at The Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria, New York, August 5-7, 2022.

American Cinematographer: How did you end up behind the camera on Brainstorm?

Richard Yuricich, ASC: During the last quarter of Blade Runner’s production, well into filming and compositing the final optical elements, Doug and I activated a “leave early” clause in our contract when Brainstorm received the green light at Paramount. Doug left to prep Brainstorm and I stayed on Blade Runner for about six weeks as visual effects supervisor, along with David Dryer, a successful commercials director who I’d worked for as an assistant cameraman in the late ’60s and early ’70s. He did a great job finishing the show. [All three were nominated for a Visual Effects Oscar for their work on the film.]

We started prepping Brainstorm to be shot in Showscan. That Doug asked me to be his cameraman was quite an honor, but I felt there were many excellent directors of photography who better deserved the job. Being his friend, admirer and partner, I told him as much and passed on the offer — three times! — while promising to still work the film. But Doug wouldn’t accept that. He told me, “You shot the first two Showscan films and understand the many layers, elements, and methodologies that go into this process. It would be a great help to me.” So I finally said yes.

What Showscan films were these?

The first two Showscan films were produced by Future General, our research and development company at Paramount Pictures. The first, This is Showscan — an homage to This is Cinerama — was shot at 72 frames per second. This was the test to see how well the process worked, what we can learn from it, and if successful, produce a proof-of-concept. We rented a Panavision System 65 High Speed camera with a limit of 80 frames per second and traveled around shooting various clips of fast action and beauty: we took it white water rafting on the Stanislaus River, snowmobiling with skiers on Mount Rose in Tahoe, on a roller coaster at Knott’s Berry Farm, and in a plane over the Grand Canyon — all of which Doug cut into a 7-minute trailer. The second film was a narrative short called Night of Dreams, and was shot sync-sound at 60 frames per second with actors, a stage, and a small union crew. We actually ran electroencephalogram tests on people watching our footage at different framerates and noticed that brainwave activity peaked around 60 fps, so that became the norm.

The VistaVision format — 8-perf 35mm run horizontally through the camera — was being used for a lot of visual effects work at the time, due to its larger-than-average format. How is 65mm different?

VistaVision, which has a 1.66:1 aspect ratio, is perfect for non-wide formats, like 1.33:1 or 1.85:1. If you extract 2.33:1 from that, up to 38 percent of the top and bottom negative area is lost. 65mm’s original aspect is 2.21:1, so a 2.33:1 extraction only loses 7 percent of the original frame.

Was 65mm equipment still widely available when you started making Brainstorm?

At Future General, we had access to whatever Paramount had on hand. Anything they didn’t have, we rented, but it wasn’t until we were hired by Columbia to do the visual effects for Close Encounters of the Third Kind [1977] that any 65mm or 70mm gear was procured. In my first week, I purchased nine 65mm cameras — two Fearless Super-Films, two Todd-AO AP-65s, and five Mitchells — plus various parts from a company called Stereovision. We took one and made an animation camera, another was turned into a rotoscope camera, another was turned into a miniatures camera. We used all the parts. The second week, I bought a single-head 65mm optical printer from Fox, made for Hello, Dolly! but not used. Another 65mm camera and 70mm optical projection head was purchased from Pacific Title.

Paramount underwrote a lot of the Showscan research and development, but the film wasn’t produced there. What happened?

A few weeks after I started Brainstorm, Paramount put the project into turnaround when it became clear that the costs associated with retrofitting theaters to run Showscan would be too much for them. We landed at MGM, but sadly, not in Showscan. Doug suggested a change for the film’s release: we would film “reality” in 1:66:1 35mm and switch to 2.21:1 full-aperture 65mm for the virtual-reality POVs.

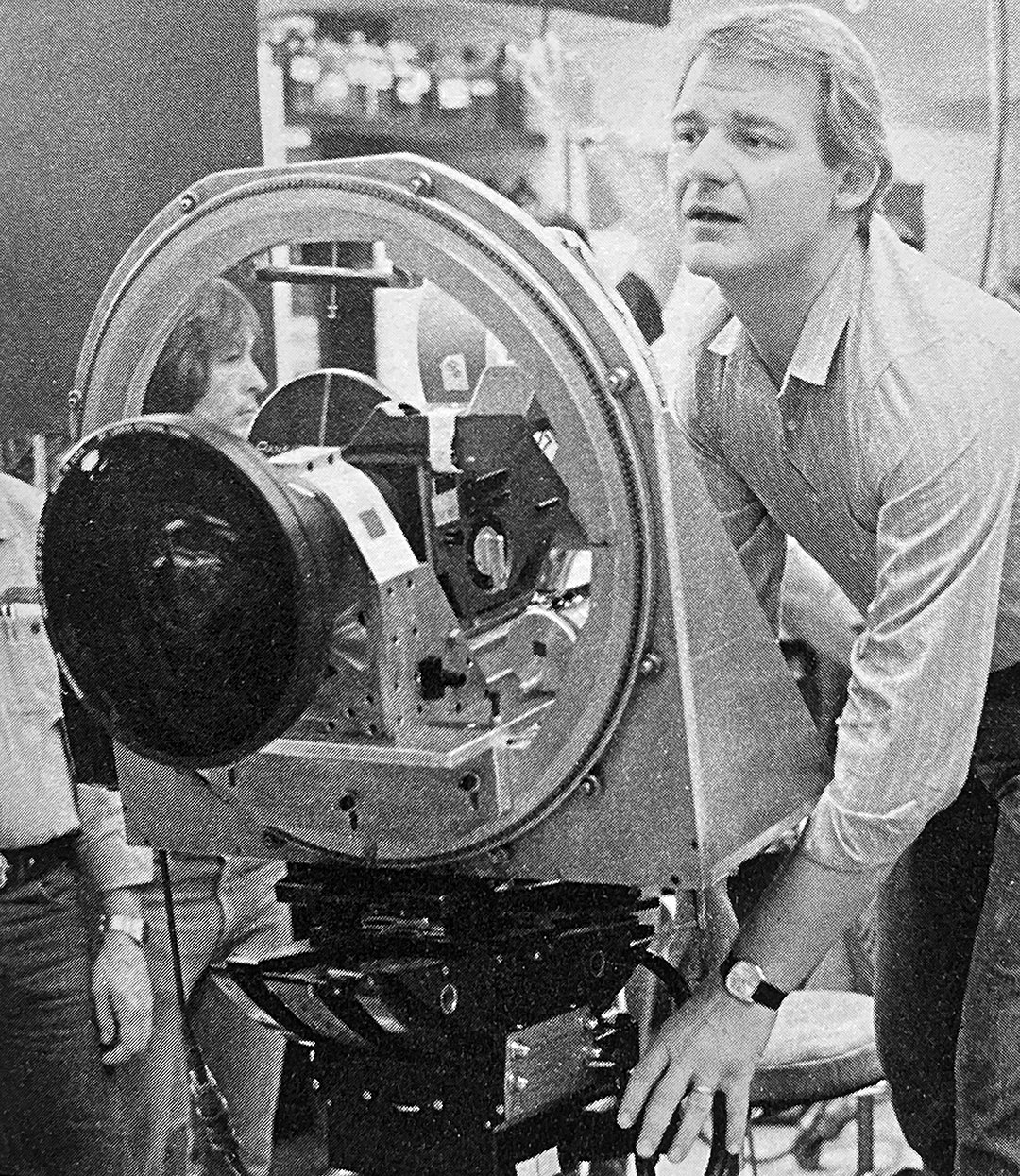

When a contemporary director like Christopher Nolan mixes large and standard formats, it can be done with help from digital post. How did you accomplish this in 1983?

It was decided that the film would have an anamorphic 2.39:1 35mm print, with the 2.21:1 65mm and 1.66:1 35mm photography holding common top and bottom framelines. The east and west borders for the 1.66:1 image were burned-in at the interpositive stage. At the time, MGM Studios had their own lab — their Metrocolor development process was excellent — and it was involved with many large-format projects. They, in conjunction with Panavison, modified cameras, lenses, print blow-up and reduction machines, and even made a number of flat 70mm release prints from the squeezed 35mm master negative.

Optically, the 65mm elements are very different from the 35mm elements. What kinds of lenses did you use?

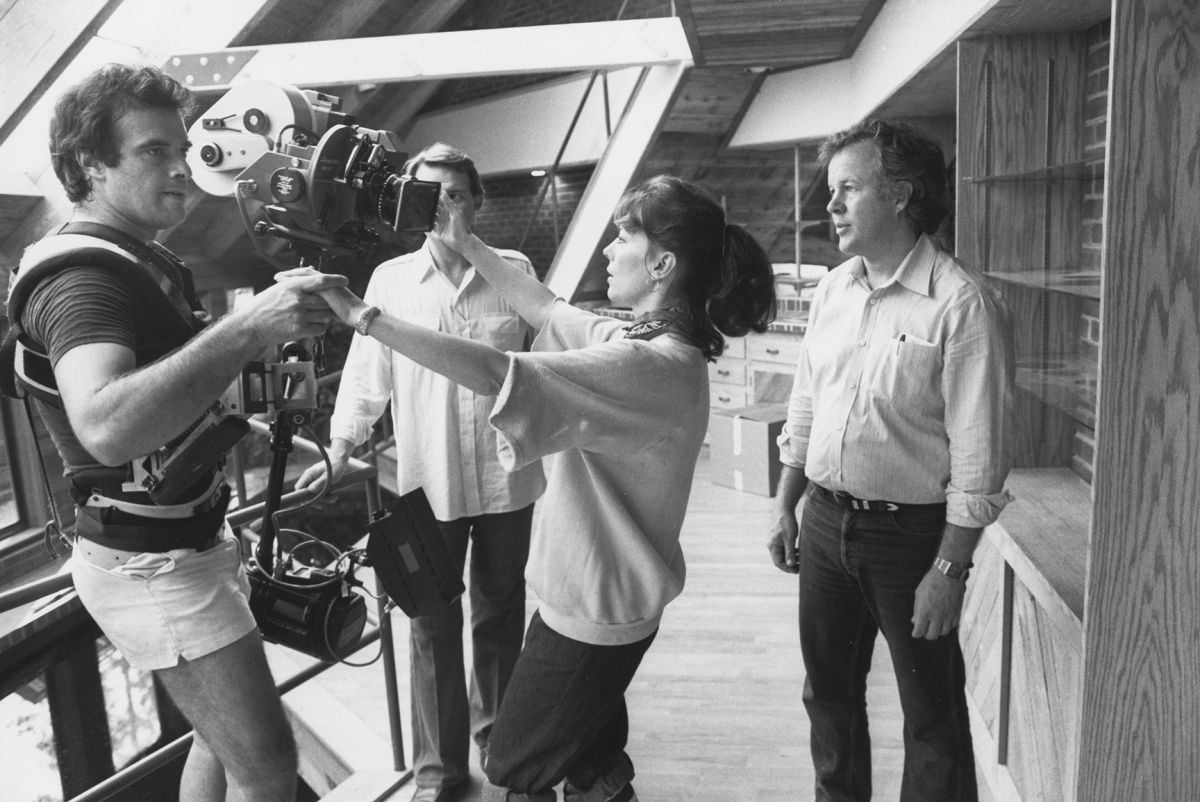

For low-light interiors in 65mm, Douglas wanted to use an 180-degree OmniVision lens designed by Milton Laikin. It was rated at f/2. We mounted it to a base with a bellows, and focus was pulled by a motorized precision lead screw that moved the lens closer to or away from the film plane. Camera assistants Craig Haagensen and Steve Smith called it the “Lotta Lens” as it was larger and weighed more than the Panaflex 65 camera body. A complementary f/5.6 wide-angle lens was used for the exterior 65mm work. We even mounted the whole thing to a Panaglide stabilizer for operator Dan Lerner, which was very useful for POV shots. Craig attached a widescreen monitor to the Panaglide, which made operating much easier.

What other in-camera optical techniques did you use?

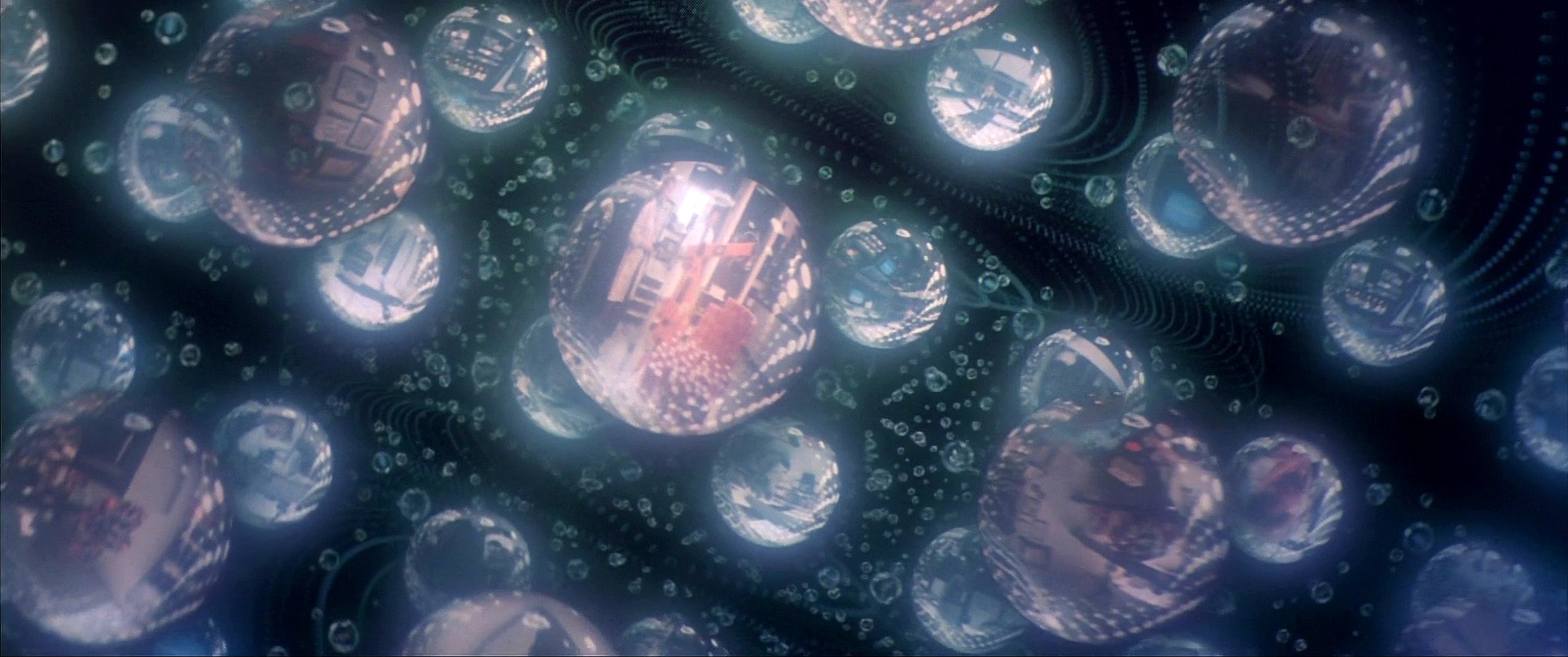

The “memory bubbles” [recorded memories depicted as floating bubbles] were a composite of 35mm, 65mm, and computer-generated elements assembled in COMPSY — a motion-controlled photographic system used for multiple pass photography, developed by EEG engineers Richard Hollander, Evans Wetmore, and Greg McMurry, ASC. Some of it was captured with an 8mm fisheye lens designed for the 16mm format, which we mounted to a 35mm Arriflex so that the entire image completely vignettes in the frame. Second-unit director of photography Bob Haagensen got many of these shots during rehearsals and in production.

Another element was inspired by Japanese Bunraku puppeteering and involved making these “angels” for Louise [Fletcher]’s death tape. Filming took place with a silk dancer in front of a black cloth background in the EEG parking lot at night. The images were burned-in using multiplane photography with COMPSY.

Can you elaborate on the multiplane process?

Disney Studios created the multiplane camera for animation work. It allows for the movement of multiple layers of artwork relative to one another at different speeds to create the illusion of depth. With COMPSY, it’s completely automated. We made multiple passes — sometimes 100 or more — on one frame with the imagery displaced a small amount in each pass.

In a production filled with technical challenges, what stands out?

All of the on-camera video playback imagery in the film was created by animator John Wash and visual effects supervisor Alison Yerxa. At the time, a very popular system for syncing the camera shutter to on-screen video monitors was available for rental from the Columbia Studios Sound Department, but the cost would be considerable for all the monitors on-camera in Brainstorm, so I asked Greg McMurry if he could work out a more affordable solution. I didn’t mind shooting with a 144-degree shutter to sync with the monitors’ roll bar, so Greg designed and built a cost-effective black box system to do just that. After Brainstorm, Greg and his crew bought the system back from EEG and formed a company called Video Image and set the industry standard for on-set video playback. That would make an interesting story, too!

Yuricich and other ASC members offer their insights on the subject of visual effects cinematography in the AC VFX report Visions of Wonder. He also dissects his approach to creating hellish visual effects in the AC article Event Horizon: Scare Tactics.

Extended coverage of the Brainstorm production can be found in Cinefantastique Vol. 14 #2, and Cinefex #14.