Ripley: A Double Life of Crime

Robert Elswit, ASC and Steven Zaillian bring the avaricious imposter back onscreen in elegant black-and-white.

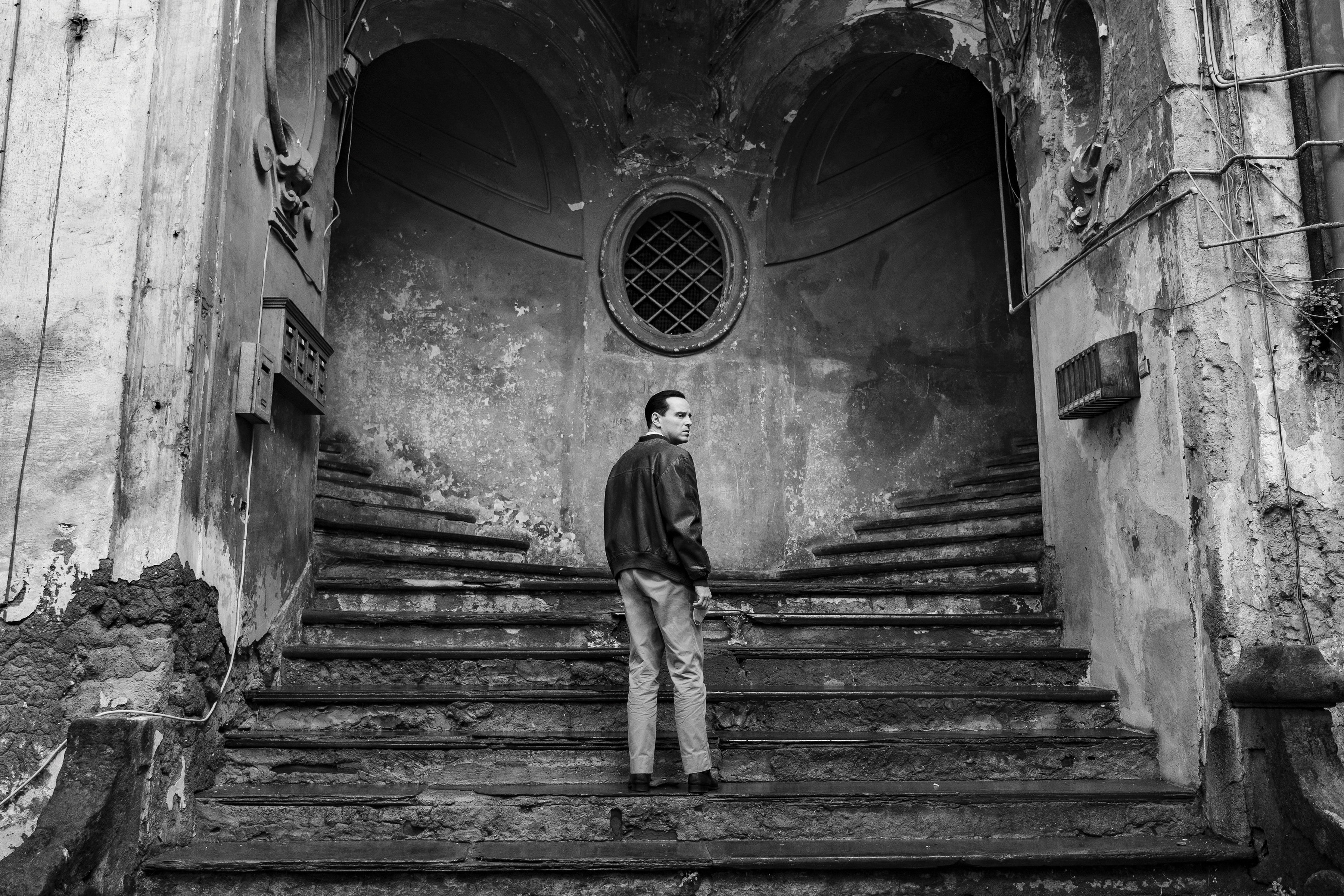

Unit photography by Philippe Antonello, Stefano Cristiano Montesi and Lorenzo Sisti.

All images courtesy of Netflix.

Tom Ripley, author Patricia Highsmith’s psychopathic social climber, is back grifting in Ripley, an eight-episode thriller written and directed by Steven Zaillian and shot by Robert Elswit, ASC.

Hewing closely to Highsmith’s novel The Talented Mr. Ripley, the story unfolds in the early 1960s, following the eponymous New York con man (Andrew Scott) on a fateful mission to Italy, where he attempts to ingratiate himself with wealthy gadabout Dickie Greenleaf (Johnny Flynn). Crimes ensue, and Ripley is soon posing as Greenleaf and cashing his trust-fund checks. Eventually, law enforcement comes calling in the form of Inspector Pietro Ravini (Maurizio Lombardi).

“[During prep] we watched every remarkable black-and-white Italian film from the ’50s and ’60s. In black-and-white, direct sun sometimes is extraordinary, and bright, poppy whites and backgrounds can look amazing.”

— Robert Elswit, ASC

Ripley’s literary debut has proven to be fertile terrain for filmmakers — notably René Clément (Purple Noon, shot by Henri Decaë) and Anthony Minghella (The Talented Mr. Ripley, shot by John Seale, ASC, ACS; AC Jan. ’00) — but telling the story in a series enabled Zaillian to devote more time to the intricate details of the character’s schemes. The Netflix production’s pace is set by many static, long takes that both ratchet up suspense and draw attention to the nuances of the story and performances. “There are sequences I wanted to play out in what felt like real time,” says Zaillian. “I knew it would be challenging, but felt if [that was] done right, it could put the audience next to Tom, even in his mind, and [create] significant tension. I’m interested in visual storytelling, and these long sequences allowed that opportunity.”

The director had a like-minded visual partner in Elswit, with whom he had worked on the pilot for HBO’s The Night Of. “Ours is a very good collaboration that I value very much,” Zaillian says of the cinematographer. “We both believe that while [the photography is] always at the service of the story, [it] should also be interesting, evocative, striking. I know what I’d like the light in a scene to look and feel like, but Robert knows how to achieve it. And he’s fearless. No situation intimidates him.”

“As I was writing the scripts, I became more certain the series should be in black-and-white. Everything was more interesting to me that way — the story, the mood, the settings, even the faces of the characters.”

— Steven Zaillian

Guided by Story

Inspired by the monochromatic chiaroscuro on the cover of his copy of the novel, Zaillian envisioned his project in black-and-white almost from the outset. “As I was writing the scripts, I became more certain the series should be in black-and-white. Everything was more interesting to me that way — the story, the mood, the settings, even the faces of the characters. This is not a pretty, color-postcard kind of story, and the story is what should guide the photography, not the other way around.”

During a scout in Italy with production designer David Gropman in early 2019, Zaillian took thousands of photos on his iPhone and converted them to black-and-white. The outbreak of Covid-19 soon sent them back home, but when travel restrictions eased, they returned to Italy multiple times to scout further.

Principal photography on Ripley commenced in July 2021 and ran through June 2022, and it was followed by about four weeks of inserts and additional photography. Elswit notes that his 10 weeks of prep were critical “because we had 860 pages and had to do block shooting in half a dozen different locations. On top of that, Steven had very specific ideas about pictorial style. He’d fallen in love with a style in Italian Baroque painting, particularly that of Caravaggio. That meant strong, contrasty lighting that would exaggerate the differences between white and black, and he would mold everything around tonal structure and graphic images.”

Zaillian even draws direct parallels between Ripley and Caravaggio, who was prone to violence and a fugitive for murder: The series includes a flashback to the scene of the artist’s crime, which took place in 1606.

That is not to say that Ripley is shrouded in darkness, however. Recalling his prep with Zaillian, Elswit says, “We watched every remarkable black-and-white Italian film from the ’50s and ’60s. In black-and-white, direct sun sometimes is extraordinary, and bright, poppy whites and backgrounds can look amazing.”

In general, the filmmakers sought to create a fresh perspective on Italy by eschewing some of the country’s best-known sites in favor of obscure backdrops in Rome, Naples and Palermo. However, they did lean into the fact that the story unfolds during a golden age of Italian cinema. They filmed some interiors at Cinecittà Studios, where Federico Fellini shot most of his films, and Zaillian even wrote a scene in which Ripley wanders onto the set of La dolce vita during its production. (The sequence was ultimately not shot, but Episode 4 is titled after the film.)

Zaillian and Elswit sometimes embraced the approach Michelangelo Antonioni used in L’Eclisse, shot by Gianni Di Venanzo, AIC: grounding images in architecture. A famous scene in Antonioni’s film shows frenzied activity at the Rome stock exchange, which is housed within an ancient temple. “The columns dominate that space,” Elswit notes. “In every shot, I feel that idea of picture plane and verticals. You never feel like you’re looking up or down because of the nature of the vertical lines. Antonioni and Di Venanzo were doing what Steven wanted to do, as well as emphasizing the structure and shapes of these things.”

Overall, though, Zaillian liked to mix it up. The director says, “I want to be able to stop on any frame and be able to say, ‘That’s a good shot.’ I like graphic angles — wide, high, low. I like to see scenes from other rooms, framing the action within the frame like in a doorway, arch or stairwell.

To me, this focuses our attention on what’s important and also creates the feeling that we’re observing.”

In fact, Ripley is full of observers, albeit powerless ones: The show features numerous cutaways to sculptures and paintings, other inanimate objects, and random animals that witness Ripley’s crimes. Many of these shots were captured by 2nd-unit director of photography Predrag Dubravcic. “The idea was that the only witnesses to Tom’s schemes and crimes are those that can’t testify — a cat, a goat, an owl, a boat, and portraits looking down at him like a silent Greek chorus,” says Zaillian.

Camera, Format and Color Space

Elswit shot on the Arri Alexa LF, which “has a big enough sensor that’s easy to work with,” he says. “I wasn’t going to be able to shoot motion-picture film, so it seemed like the right way to go, and I could control it.”

In addition, “There were going to be a lot of visual effects — painting things out and adding others — because there were set pieces, like train stations, where nothing was period-correct. And for the murder sequence on the boat, we wanted the biggest file we could get so the visual effects would be invisible.”

Elswit shot in the LF Open Gate ArriRaw 4.5K format and framed in 1.78:1 with 5-percent scaling, according to DIT Marco Coradin. Working with supervising colorist and ASC associate Stefan Sonnenfeld at Company 3, the cinematographer set up a LUT that emulated Eastman Plus-X 5231. They monitored in standard Rec. 709 color space.

Originating in color, the filmmakers started off switching between color and black-and-white monitoring, and when that proved inefficient, they set up two simultaneous pipelines: a color version with a washed-out look reminiscent of bleach-bypass, and the monochrome version.

Starting with Rec. 709, the black-and-white version was created through desaturation and contrast correction, with contrast according to Robert’s desire, and the color version was also very desaturated, with similar contrast,” Coradin explains.

Custom Lenses

Elswit paired the Alexa LF with the new Panavision VA larger-format spherical primes. The production’s 1st camera assistant, Erik Brown, notes that a few of Elswit’s favorite focal lengths — 28mm, 40mm and 65mm — were not yet available in the set, so Panavision senior vice president of optical engineering and lens strategy Dan Sasaki, an ASC associate, built them for the production.

“They’re made to look like Super Speeds from the ’70s,” Elswit says of the VAs. “There’s built-in chromatic aberration, and Sasaki designed some spherical aberration into them. There may be a little more vignetting. With the digital sensor, we want lenses with character. They have marvelous falloff. I did a lot of medium close-ups with the 40mm and the 50mm, where the out-of-focus look of the background and people at the sides [of the frame] is really nice.”

Elswit also called on the 24mm and 35mm, and the 65mm was used for macro insert work. Panavision 70 zooms were used to problem-solve, as in a scene for Episode 5 (“Lucio”), in which Ripley takes a car key belonging to Dickie’s suspicious friend Freddie Miles (Eliot Sumner) and tries to find out which car parked outside is Freddie’s. The camera follows Ripley as he crosses the road and approaches the first car. “The challenge was, ‘How do we get across the street and get tight on Tom?’” says Elswit. He suggested to Zaillian that they combine a dolly move with a zoom-in that would end close on Tom’s hand as he tries the key. “I thought Steven’s brain was going to explode at the suggestion,” Elswit recalls with a laugh. “The whole series is prime lenses, and mostly just four of them. We never did the zoom-in again because there was no reason to.”

Otherwise, zooms sometimes came into play in day-exterior crane work, essentially functioning as a variable prime, says Brown. “There were also times when we lined up a crane shot with the zoom and then replaced it with a prime to do the actual shot,” he adds.

Panavision provided larger-format zooms optimized to match the visual characteristics of the VA primes: a custom-made 16-28mm T3, a 28-80mm T3, a 70-200mm T2.8 and a 200-400mm T4.5.

Elswit estimates that 90 percent of Ripley was a single-camera shoot because Zaillian’s compositions were so specific. “Sometimes we could have two cameras, in which case we’d be looking at two different directions, but we never had the cameras side by side to make different-sized shots. Steven was not looking for coverage.”

Elswit operated A camera, as he usually does, and Alessandro Brambilla and Emiliano Leurini split the B-camera work, using an Arri Alexa Mini LF. The crew carried another Mini LF for Steadicam, but Elswit recalls that the rig was seldom used .

The cinematographer usually operated remotely with a Cinemoves Matrix four-axis gyrostabilized head, but he went handheld for certain rough-and-tumble moments, including some shots in the story’s fateful boat ride (Episode 3, “Sommerso”) and when Ripley deals with Freddie’s body in his apartment (Episode 5, “Lucio”). He mostly shot between T2.8 and T4, and for some nighttime shots at T2.

A Dark Road

The most challenging night location was the Via Appia, an ancient, unlit, cobblestone road outside Rome lined with stone-pine trees. In the sequences, which appear in Episodes 5 and 6 (“Some Heavy Instrument”), Ripley leaves Freddie’s body in the latter’s Fiat at the side of the road, and the police later arrive to study the crime scene.

“When you’re in the city, you can create the illusion of ambient lighting from sources such as streetlights and buildings,” says Elswit, “but out there in the middle of nowhere, what can you do but try to make it feel like moonlight?”

The crew set up an Arri 18K Fresnel on a condor hidden by a giant pine to simulate direct moonlight in wide shots and reflect off the wet cobblestones, and another 18K at the other end of the road for a strong backlight. For ambient moonlight, they floated a 30'x20' soft box with 12 Arri SkyPanel S60-Cs behind Light Grid Cloth.

“We wanted to get as much spread as possible on the road where we were shooting the actors,” says gaffer Francesco Zaccaria. “The SkyPanels were set to a low intensity, about 30 percent.” The ambience was amplified by a De Sisti Super LED F14 reflecting off a 12'x12' frame, and more of the same units were hidden behind trees on either side of the road.

Fomex FL1200 flexible LEDs were brought in for close-ups and for contrast to add to the creepy atmosphere. Zaccaria notes the units are “very lightweight and easy to control and use,” and they could be quickly shifted depending on the actors’ positions and movements.

Murder at Sea

Coincidentally, Zaccaria worked as a best boy on Minghella’s The Talented Mr. Ripley. On that production, the filmmakers actually went out to sea to shoot Tom (Matt Damon) and Dickie (Jude Law) on the boat. Capturing the scene for Ripley involved four weeks of work on location as well as onstage.

Shots of Tom and Dickie motoring out were done at a beach in Anzio under partly sunny skies. For the murder, Zaillian wanted ominous overcast skies for both artistic and practical reasons. The production commandeered a large pool outside Rome, which key grip Chris Centrella surrounded with greenscreen hanging from scaffolding that was topped by a large diffusion cloth.

Elswit wanted to create a sense of direction for a soft sun, and he used up to three 18Ks positioned above the greenscreen that could be angled as desired, bolstered by De Sisti lights. Several 9K HMIs were positioned at the front to bounce light from the water onto the boat. Elswit credits Wētā FX for their work in compositing skies into the water footage.

Controlled overcast lighting was needed to sell the sense of movement, as the filmmakers planned to use a time-honored technique in the contained space. “The boat was relatively static,” Elswit explains. “We formed a wake behind it and created the illusion of movement with the camera moving toward the boat, and if we wanted the boat to turn sideways, we would have the camera do that.”

In their setup, the lighting doesn’t change, but if the boat were actually moving under a sunny sky, light and shadows would shift, tipping off viewers to what Elswit calls a “transfer-of-motion shot.”

The show’s 2nd camera assistant, Stefano Palla, says the team used up to three cameras mounted on cranes — a 50' Technocrane with an Oculus head, a MovieBird 45 with a Flight head, and a GF-8 with a HydroFlex HydroHead so it could get down in the water — to capture more than 150 shots for the boat killing. “We shot the beginning and the end of the sequence — the fire and the sinking of the boat — on location, in Anzio. We had a crane on a barge in the shallow seawater and we did some handheld shots on the boat. However, the main part of the sequence was done in the swimming pool. The grips built three greenscreen walls around the pool, but the green cloth was also deployed on the pool’s edge and inside the pool itself.

Palla adds, “We did so many camera positions that it was almost hard to keep track of everything, but shooting that way allowed Steven to give the sequence the rhythm he wanted. He could indulge in a pause, or cut the action with as many points of view as he wanted to create more suspense.

Hiding in Plain Sight

For a scene in Episode 8 (“Narcissus”), Ripley lights his environment in a style that channels his newfound Caravaggio obsession. Living the high life in Venice, he has to revert to his actual identity as Tom when Inspector Ravini comes calling — though the officer previously met him while he was posing as Dickie.

Zaillian wrote the scene so that Ripley changes the lighting in his house in an attempt to deceive Ravini, who will visit him at night. The den where they meet has several chandeliers, but Tom only keeps one on above where the inspector will sit. There are also numerous table lamps, but he will only have three on: one near himself, one near Ravini and one in the background. He replaces the bulb in the lamp close to him with a lower-intensity bulb and positions the lamp to cast him in silhouette.

“The idea is he’d light himself in such a way that you wouldn’t see him clearly,” Elswit says. He adds that convincing viewers that Ravini, Elswit and Zaillian infused the series with film-noir ambience. wouldn’t recognize Tom was “the trickiest part of the narrative” and required some additional shooting. Zaillian later decided to further disguise Tom with a beard and wig, which was accomplished in post.

The location was the 15th century Palazzo Contarini Polignac, which presented some lighting challenges. “They wouldn’t let us hang anything off the ceiling,” Zaccaria recalls. “But we could hang a couple of Fomex [FL1200s] on a long pole off a mezzanine over the actors on the main floor.”

Greenscreen was positioned on the balcony outside the windows to facilitate the later addition of a CG view of the glistening canal. Two Fomex units dialed to 10 percent were placed above the windows. Ravini was surrounded by three FL1200s amplifying the practical lamp and chandelier, while the only additional light on Ripley was a less powerful Fomex FL600.

Although Netflix is exhibiting Ripley in black-and-white, the studio also asked the filmmakers to grade a color version. “That was the first time we’d seen it,” Elswit says. “We thought, ‘How do we do this?’ because the whole thing was designed [for black-and-white], and my lighting is very contrasty and shaped. Lighting people’s faces wasn’t about using an LED soft box that feels like ambient daylight from some unknown window — I always had strong shadows. The color version looked like a film shot in 1956!”

Subsequent to talking to AC for this article, Elswit was interviewed by Caleb Deschanel, ASC for this episode of our award-winning interview series ASC Clubhouse Conversations: