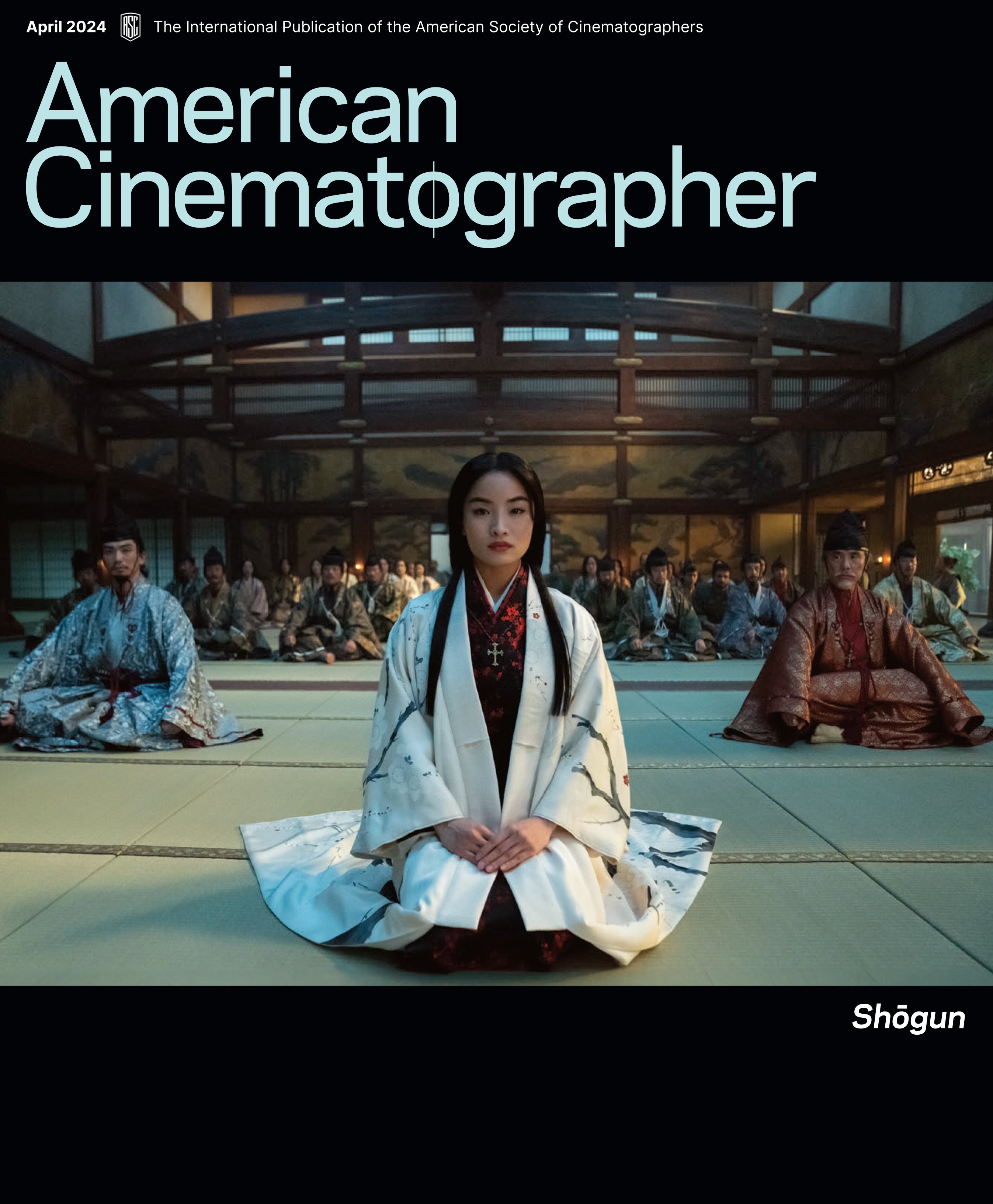

Shōgun: A Stranger in a Strange Land

Sam McCurdy, ASC, BSC; Christopher Ross, BSC; Marc Laliberté, CSC; and Aril Wretblad, FSF re-create the treacherous world of medieval Japan.

Unit photography by Katie Yu. All images courtesy of FX

The cinematographers of Shōgun were tasked with delivering a fresh take on classic source material. That meant simultaneously transporting viewers into the milieu of Edo-period Japan and the perspective of an interloper surviving within it. Christopher Ross, BSC — who shot the 10-part FX miniseries’ first two episodes, “Anjin” and “Servants of Two Masters” — says this approach reflects the “political minefield” at the heart of its drama: “We’re delving into a hierarchical civilization, and how the Japanese view a ‘primitive’ European. We wanted to capture medieval Japanese life through the eyes of a stranger, and, equally, to immerse ourselves in that world and view the stranger as an outsider.”

Inspired by real events and based on James Clavell’s 1975 bestselling novel of the same name, Shōgun is set in Japan in 1600 as a civil war looms and the British and Portuguese compete for a commercial foothold in the country. A council of five regents is tasked with ruling the country until the son of the Taikō (the emperor’s chief adviser) comes of age. But a power struggle between two of them — Toranaga (Hiroyuki Sanada) and Ishido (Takehiro Hira), the latter of whom is supported by the other three regents — sparks constant conflict.

Englishman John Blackthorne (Cosmo Jarvis) enters the fray when the Dutch ship he’s piloting washes ashore in Toranaga’s territory. Toranaga soon realizes the outsider’s talents might prove useful, and he grants Blackthorne a home; a consort, Fuji (Moeka Hoshi); and a translator, Mariko (Anna Sawai). But Toranaga keeps his ambitions close to his chest.

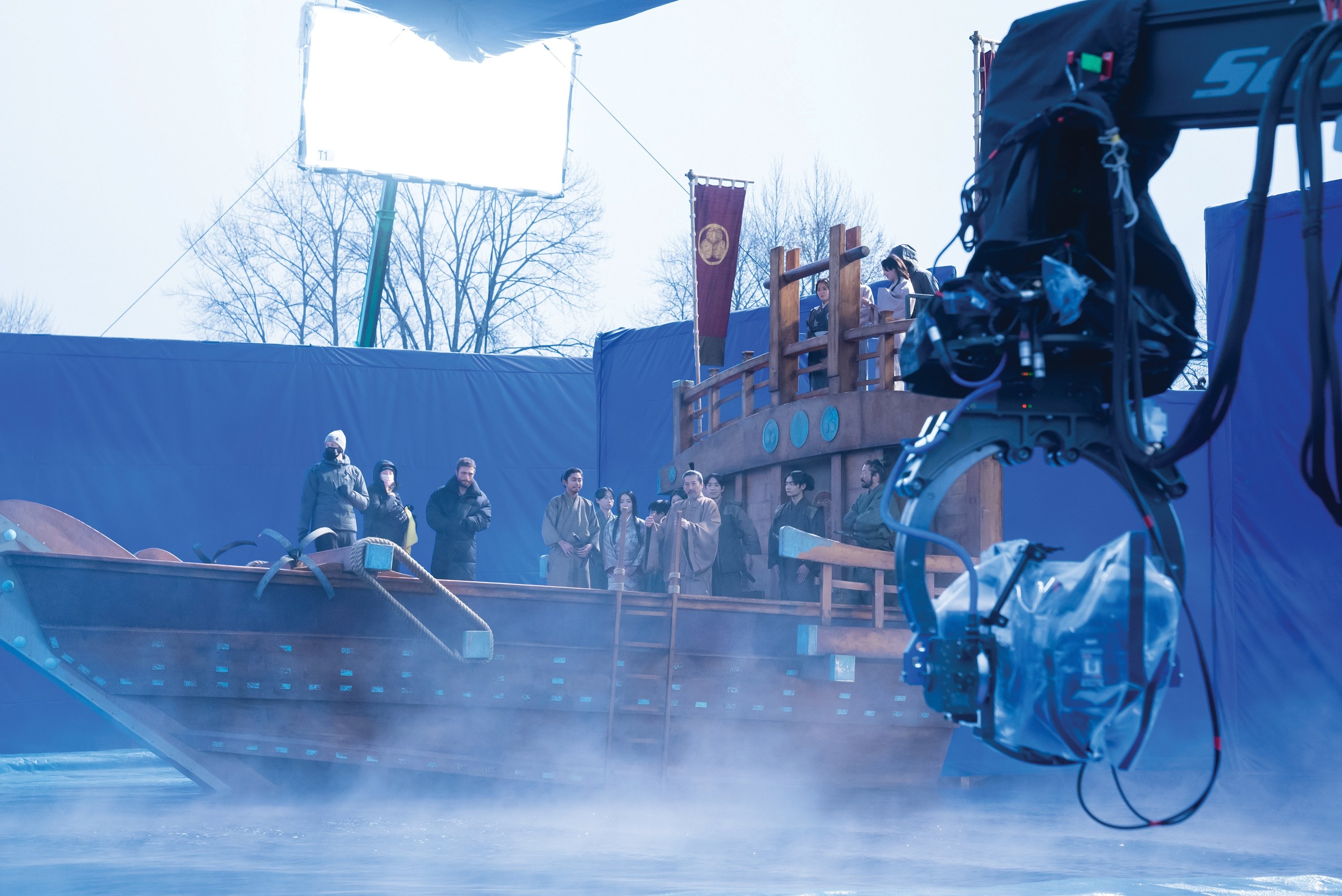

To re-create the story’s feudal-Japan setting, the production set up shop at Mammoth Studios in Burnaby, British Columbia, taking advantage of the region’s forests, fields and coastline. The initial team included Ross, showrunner Justin Marks and director/executive producer Jonathan van Tulleken. Once the crew was fully assembled, Ross shared shooting duties with cinematographers Sam McCurdy, ASC, BSC, (Episodes 4, 5, 7, 9 and 10); Marc Laliberté, CSC (Episodes 6 and 8); and Aril Wretblad, FSF (Episode 3).

Ross notes that van Tulleken, a collaborator since the British superhero series Misfits, likes to prepare a “mood film” for his colleagues that uses film clips to set the tone for the photographic style and editing approach. For Shōgun, scenes from Apocalypse Now figured prominently, as did The Revenant [AC Jan. ’16] for its “rough-and-ready first-person style,” says Ross. “It was about trying to create a robust masculinity and savagery around Blackthorne, who’s viewed as such an outcast.

“There are also elements of The Insider [AC June ’00] in terms of political intrigue and Macbeth [2015] in the way we wanted it to feel intrinsically earthy, with the humans and environment enwrapped in one another. We wanted to create some poetry and connection to nature with the Japanese characters, who are more civilized and at one with the universe.”

Total Immersion

Shōgun’s 21-month shoot began in September 2021, when Ross was coming off of the 2022 feature The Swimmers, which he shot with the Sony Venice. “I loved the way it works in terms of highlights, and I liked it combined with anamorphic lenses, so I was pretty sure that it was the camera for Shōgun,” he says. Tests at William F. White International in nearby Vancouver confirmed his belief.

“[Van Tulleken] and I talked about the granularity we wanted in the wilderness images — the feeling of really being in nature, the smoke and the roughness of medieval life,” Ross continues. “I was drawn to the Hawk class-X anamorphics, particularly for the softness and the falloff of the wider lenses toward the edges of the frame. I thought that served Blackthorne’s first-person narrative well.”

Shooting a previous FX project, Trust, Ross learned that a 2.0:1 aspect ratio was as wide as the network would go and they required a 4K deliverable, so the production shot full 6K and cropped to 4K 2.0:1. “The combination of the class-X and the Sony Venice allowed me to hit the 4K-resolution mandate of the 2.0:1 aspect ratio.

The production also carried a Sony FX3, which was used as a crash camera and to shoot nature inserts, architectural elements and some time-lapse material.

Throughout the shoot, the filmmakers maximized characteristics of the Hawks to emphasize the chaos unfolding in front of the camera. “There’s no blueprint for creating life 400 years ago, so you have to experiment and take a bold leap — you have to grab the audience’s attention,” says Ross.

He shot mostly in a range of T2.3-T2.8, leaning toward open for maximum aberrations and the Petzval-swirl effect. For Blackthorne’s scenes, Ross stuck mostly to 35mm and 45mm focal lengths, occasionally going to 28mm; for scenes in the Japanese court, he favored the 55mm and 80mm. “We didn’t go longer than that in the first two episodes because we were generally close to the characters and photographing over shorter distances,” he explains. Tight framing in Blackthorne’s scenes emphasizes his feelings of alienation.

Taking a cue from the classic work of Yasujirō Ozu, the filmmakers shot from low angles for interiors that featured Japanese characters seated on the floor. Typically, the A camera was on a Servicevision Scorpio 23' crane while B-camera operator Shane McLeod would look for other moments. “Shane’s work with the B camera was pivotal for sowing the seeds of the intrigue and power play,” Ross says. “While the A camera was telling the scripted Blackthorne-Toranaga narrative in their scenes together, Shane was digging into the subtext and tying up the unwritten eyelines between Mariko and Blackthorne. Without this subtle work in the early episodes, audiences might find that later alliances are harder to get behind.”

An Expanding Scale

Wretblad and director Charlotte Brändström, who had collaborated on the 2021 Swedish miniseries The Unlikely Murder, took over for the series’ third installment, “Tomorrow Is Tomorrow.” Wretblad notes that the story’s scale expands and the pace quickens in their episode, which called for a different visual approach. “We had lots of actors and extras in movement in multiple scenes, and we needed to take that, and fairly long resets, into consideration,” he says.

Consequently, they used up to four cameras for some scenes to get the coverage that was needed. “We’d usually have the A camera, operated by John Clothier, and B camera, operated by Scott Nuttall, covering the main action and the other two cameras capturing reactions and wider shots.” He adds, “We wanted to be physically close to the actors with the cameras, using lenses at the wider end to get the immersive feel that approach lends. But, at times, we would have to sacrifice some of that and step back a little to get all of the camera angles in.”

In one scene, Blackthorne, Mariko and Fuji are escorted out of Osaka after a failed attempt on the Englishman’s life, and they find themselves in a forest after sunset. They suddenly come under attack from a rival faction launching flaming arrows from a nearby ridge. The scene was shot in a nature preserve that restricted the use of certain equipment. Faces were lit by the soldiers’ torches, “which were augmented for close-ups,” Wretblad says. The crew lined the forest edge with condors — which, the cinematographer notes, were “rigged with Dinos, using narrow bulbs and CTB to push cool moonlight through the thick branches” — and floated three Novo Lighting Sphere 9' tungsten balloons between trees for ambient moonlight. “I wanted the balloons blue enough to separate properly from the torches,” says Wretblad. “Novo custom-made a Full Blue ‘gel sock,’ because we wanted to be able to adjust the level while still keeping [the balloons] blue. When dimmed down to the right level, they got a nice blue tone that wasn’t too warm.”

A Muted Palette

McCurdy shot Episodes 4, 5, 9 and 10 (“The Eightfold Fence,” “Broken to the Fist,” “Crimson Sky” and “A Dream of a Dream”) at the direction of Frederick E.O. Toye, with whom he had previously collaborated on Netflix’s Lost in Space. For Episode 7 (“A Stick of Time”), he worked alongside director Takeshi Fukunaga.

McCurdy emphasizes the importance of Carlos Rosario’s costume design, which features blacks, browns, whites and grays. The series’ overall palette is muted; gold and woody hues permeate production designer Helen Jarvis’ period architecture. Against this, the occasional red — such as the kimono and makeup of courtesan Kiku (Yuka Kouri) — stands out. “Carlos’ costumes depict a hierarchy and class system,” explains McCurdy. “The textures, form and colors were sympathetic to the production design and makeup design — and, therefore, to the cinematography. It allowed us to pop lipstick or an oil lamp without fighting against the costume. They were perfect in the rain, sun, moonlight and oil light.”

The cinematographer notes that he was fortunate to participate in the project’s preproduction phase. “Christopher and I go back many years, and I prepped with him and Jonathan, which gave me time to understand the language we were starting with,” he says. “Then, Fred and I discussed how we were going to develop that language and twist it as we got into the center of the story. We would ask, ‘What do we want to push: The scale? The romance? The energy?’”

In Episode 4, they push the romance. McCurdy calls the camera language “gentle, soft and subtle” as the relationship between Blackthorne and Mariko develops — particularly in a scene in which the pair meet on a rocky outcrop, and another at night in a rock pool. “The camera drifts lightly around the rock pool, engaging the characters as they become more comfortable with each other,” he notes. In later episodes, when Mariko’s absent samurai husband, Buntaro (Shinnosuke Abe), unexpectedly returns, the style shifts to a “brutal style of extended shots, firmer cuts and prosaic movement.”

In Episode 7, the filmmakers emphasize the presence of an ominous force, suggested by pervasive mist. After Toranaga’s army has been decimated, he calls on his half-brother, Saeki, for help, and Saeki arrives with his own army and unclear motives.

“That episode has its own aesthetic,” McCurdy says. “It’s about something we hadn’t encountered before, and so we made the camera movement and blocking of scenes different. There’s an oppression coming; we had very wide shots that we would try and hold for as long as possible that would press and press in an overbearing way. We would purposefully push the camera into the scene — into the center of the frame, with no lateral movement as we pushed, just straight in. [And these] wide shots would often be at a height where we could feel the world ‘move’ — low down and pushing over land, or high up overhead and pushing straight into the center of the frame and the ground, to feel the weight of the world as we pushed.”

In Episode 9, Mariko, Yabushige and Blackthorne return to Osaka to address Ishido and Lady Ochiba (Fumi Nikaido), the heir’s mother, with whom Ishido has arranged an advantageous engagement. In the great hall, Mariko incurs Ishido’s wrath by telling him Toranaga isn’t ready to surrender, and that she is taking Toranaga’s wife, Kiri (Yoriko Dōguchi), and consort Shizu (Mako Fujimoto), who have been held at the castle, back to him.

The scene was shot in a soundstage and occurs as the sun sets, and McCurdy wanted to show that progression. The castle’s shoji sliding doors were left open to let in as much natural light as possible, as well as illumination from practical braziers in the garden. Because the real buildings’ wood, paper and straw construction was flammable, interior firelight would have to be minimal, so the art department set up just a few oil candles. “All of the light had to feel like it was coming from outside for it to feel natural,” the cinematographer notes. “So, we had to make the sun source as large as we could and make the sky feel like it wrapped the entire studio.”

Keeping the sun source in one spot allowed A-camera operator Daryl Hartwell and B-camera operator Marco Ciccone (who finished the series) to freely move about — for example, following Mariko’s entrance — as long as they didn’t walk in front of the source. That source was an Arri SkyPanel S360-C on an arm pointing into the set, flanked by a 10K on either side, with all three fixtures diffused through Full Grid Cloth. The same lighting combo was used on the backdrop.

“I left it to be slightly overexposed,” McCurdy explains. “We had SkyPanels in the ceiling and on the floor.” He adds that the crew built the “sky” in the ceiling of the studio “out of some 200 SkyPanels with mid-gray diffusion, [and] we feathered the intensity of the SkyPanels in color and brightness. [The SkyPanels] would go from a deep, warm, sunset-orange through to a deep purple-blue at the opposite side — mimicking a real sky at sunset — and [transition] in intensity from about 60 percent at the center to around 4 percent at the sides.”

Turmoil and Uncertainty

For Episodes 6 (“Ladies of the Willow World”) and 8 (“The Abyss of Life”), Laliberté worked with directors Hiromi Kamata and Emmanuel Osei-Kuffour, respectively. He says he was fortunate to collaborate with A-camera operators Clothier (Episode 6) and Steve Krasznai (8). For most interiors, they worked with a remote head on a dolly, but in the regents’ meeting room or on an exterior, the camera was on a Supertechno 50.

Laliberté says he only opted for handheld once, in Episode 8, when Blackthorne, who has been separated from his crew since their capture, encounters one of his men — who has not fared as well — in Edo, and they come to blows. “We said, ‘Let’s just be in with him,’ and it’s down and dirty,” Laliberté recalls. “We’re out of the royal palaces, where we tried to be more composed and lyrical and prescriptive with our camera movement. We felt handheld spoke to Blackthorne’s inner turmoil and uncertainty about his future direction.”

The cinematographer says that when he first arrived on set, he was “blown away” by the work key grip Finn King, gaffer David Tickell and rigging gaffer Jarrod Tiffin had done in setting up 10'x20' SkyPanel soft boxes on overhead circle trusses that could be lowered, raised and rotated 360 degrees.

“If you want a soft sunlight push, the key is to take the soft sources as far away as you can to make it feel like one big source, and that was their solution,” Laliberté says. “Additionally, on each wall, we had soft boxes that could move left or right 20 feet and forward or back 15 feet. So, no matter what direction we were shooting in, I could always say, ‘I want my sun to be just off the back cheek,’ or wherever it was.”

While Laliberté focused on the soft boxes, Tickell would instinctively know what was needed on the floor to fill in any dead spots, often using Arri 18K HMIs, M40s and M90s. As much as possible, they used real candles and LED candles as a key light on faces in night scenes. “If necessary, we would use Vortex lights and SkyPanels with a lot of softening to mimic the firelight,” Laliberté adds.

Although historical accuracy was a priority, the filmmakers had to deviate from it in one aspect in order to achieve the best image. “The Japanese advisers told us the shoji screens were always closed,” Laliberté explains. “But that just made it feel like we were on a set the whole time, because there was no depth. Generally, you want to find depth and create layers. We advocated to the advisers that we needed to bend that rule for the sake of how the show was going to look.”

Tech Specs

2.0:1

Cameras | Sony Venice, FX3; Phantom Flex4K; Arri Mini LF

Lenses | Hawk class-X, V-Lite, Vantage One; Angénieux zoom;

Arri/Zeiss Ultra Prime; Laowa; Sigma Cine FF High Speed

Spotlight on Camera Movement | Intimacy and Warfare

Shōgun’s four directors of photography tapped a gamut of gear to move the camera, in keeping with the ebb and flow of the drama.

“I thought the tools were used well with the story, which travels from intimate, dramatic moments to battle scenes and action,” says A-camera operator John Clothier, who worked on Episodes 1-6 and collaborated with all four cinematographers.

Steve Krasznai took over A-camera operating duties for Episodes 7 and 8 and handed off the last two to Daryl Hartwell.

“Even the more ritualistic [Japanese] cultural moments would always have some movement,” notes Clothier. “In situations like that, where we wanted to be slow-moving and formal, we’d use the dolly, while Steadicam would be great for walking and talking.”

Episode 1 scenes in which the Japanese clash with Blackthorne’s crew in their shipwrecked vessel and, later, in a pit in which the foreigners are imprisoned, were shot mostly handheld to underscore the pirates’ rough-and-tumble nature. When Blackthorne climbs out of the pit, two soldiers grab him and force him to the ground, and the Englishman’s disorientation is conveyed by a near-360-degree camera turn executed with a Spacecam M7 Evo remote head on a Supertechno 50.

As a counterpoint, sequences involving Japanese characters were shot with more stable framing and single-axis moves, according to Ross. When the feuding regents discuss what to do with Blackthorne, the drama is conveyed predominantly through facial expressions and head turns; small push-ins underline one regent’s one-upmanship over another.

The Supertechno 50 was also used in some of the bigger interior sets, but Clothier found it especially useful outside on the Taurus four-wheel base, and he praises driver Lyle Contaoe, pickle operator Bryce Shaw, and A-camera dolly grip Chris Jones on the bucket for dealing with challenging terrain.

“We had a lot of West Coast mud to get through,” Clothier says. “But if you think through your shots and put the base in an intelligent spot, it can be very economical timewise, in terms of the amount of movement and flexibility you have with it.”

McCurdy calls Shōgun predominantly a “single-camera show,” but outdoors, he often liked to have a 50' crane and a 30' crane “dance” with one another to develop the movement of a shot. Sometimes the team would conclude that laying track for a dolly was the way to go.

Many mobile high-angle shots were used for scope, and these tapped the Supertechno 100. For example, in Episode 3, when Ishido’s men escort Blackthorne, Mariko and Fuji out of Osaka, a bird’s-eye camera tracks their procession outside the castle grounds, passing over a couple of walls and tilting up to show the group walking over a bridge, revealing distant forests and mountains. (CG elements were added by visual-effects supervisor Michael Cliett and his team).

In similar situations, a drone was sometimes used. Ross used a DJI Inspire 2, whereas Wretblad went with the Freefly Alta X with an Arri Mini LF and a Sigma 20mm T1.5 Cine FF High Speed Prime mounted to a Mōvi Pro.

Several wire-rig assemblies were arranged by key grip Finn King, including one used at the end of Episode 1. A bound Blackthorne disembarks the Portuguese galleon that brings him to the city as the camera sweeps over the harbor and through a busy street and then tilts up to the sky, where it becomes a VFX shot heading to the castle.

“We wanted to be immersed in Blackthorne’s perspective as he’s piecing together how he’s going to keep himself alive amid all this,” Ross says. “[Director] Jonathan [van Tulleken] was always talking about embedding the imagery into the characters’ story.”

Editor’s note: Subsequent to the publication of this article, McCurdy was interviewed by Adam Bricker, ASC for this episode of ASC Clubhouse Conversations: