Three Moods Prevail in Dead Presidents

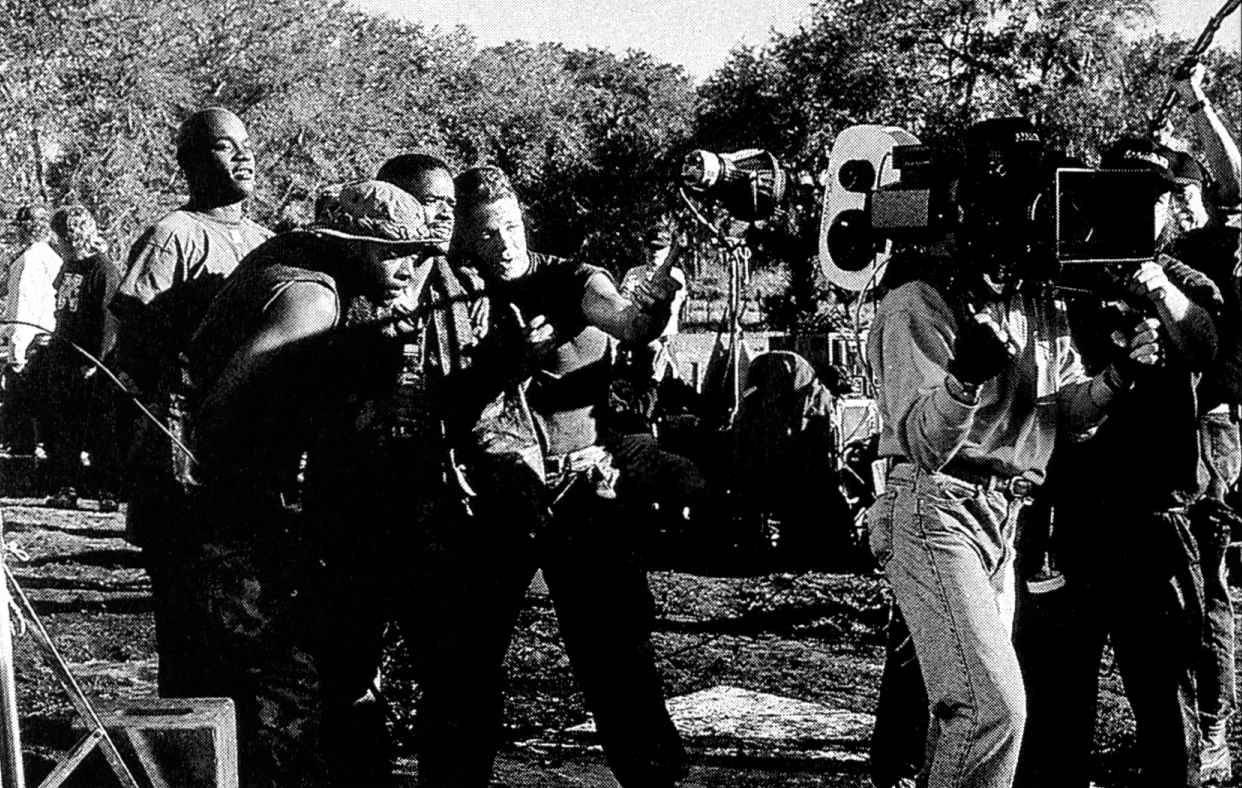

Cinematographer Lisa Rinzler and co-directors Albert and Allen Hughes conspire with danger and darkness in their Vietnam-era heist picture.

This article was originally published in AC September 1995.

Menace II Society (1993), an ambitious and powerful film that broke new ground with its portrayal of a violent African American sub-culture, left critics and audiences electrified with its brave filmic vision — boldly announcing the arrival of co-directors Albert and Allen Hughes. Dead Presidents, the 22-year-old brothers' highly-anticipated second feature concerning the travails of a young black Vietnam vet, continues the promise of their directorial debut, while the images in both films proclaim the talents of cinematographer Lisa Rinzler — demonstrating daring style and the innate ability to tell a story with a camera.

As a young girl, Rinzler had a fascination with drawing and painting; the road to cinematography began more subconsciously. Black-and-white films such as Sunset Boulevard, Johnny Apollo and Madame X left strong impressions, which created a fertile terrain in her imagination. "I took away psychological images from those films," Rinzler recalls. "To see them today they don't look anything like the feeling I remember them creating, but that is what shooting is about — what you perceive something to look like, rather than what it actually does look like."

Rinzler initially pursued art studies at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, where she began to uncover a yearning to express herself through cinematic imagery. "I was painting with motion a lot," she remembers. "Suddenly, light wasn't the only issue. Motion was involved and I couldn't quite get it all in painting. I must have had some dream I don't remember, because one morning I woke up and said, 'That's it! I'm switching to film.'"

Rinzler made her first short at Pratt and then applied to the film program at New York University as her desire grew. "I knew instantly that I wanted to become a cinematographer. Operating the camera felt very natural for me," Rinzler explains.

At NYU, Rinzler had influential experiences that helped to shape her career. As a production assistant on a professional film shoot, she quickly found herself in the camera department, where she gained valuable firsthand training. She also shot two short films for photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, who taught her "lessons about commitment — about being more into your subject than just photographing it," Rinzler observes. "The subject comes first; photographing it naturally, organically, comes second. I was enamored with Robert because of his commitment."

After leaving NYU, Rinzler learned her craft as a camera assistant to director of photography Nancy Schreiber, ASC in documentaries and as second assistant to Fred Murphy, ASC in features. She calls Murphy her "mentor and biggest encourager and supporter. Fred had me diagramming his lighting setups. There was a great beauty in studying someone's work that closely. It made me look at every lighting unit and question what it was doing.

"Fred also taught me about being on the set. He was such a gentleman. A large part of being a director of photography is functioning on the set. It's being diplomatic and dealing with the production aspects, equipment coming and going, with time pressure and people leaning on you. Fred had a very gentle manner, yet he stuck to his needs and fought for them."

Rinzler worked with Murphy on Eddie and the Cruisers and the television film Trackdown: Looking for the Goodhar Killers, and was a first assistant on Death of an Angel, starring Bonnie Bedelia. Her participation as a camera assistant on many documentaries, including Seeing Red and Abortion Clinic, helped hone her technical skills and her ability to work fast under constant pressure. These projects also served to develop Rinzler's burgeoning social conscience.

Rinzler has gone on to shoot a number of documentaries, including Hookers, Prostitutes, Pimps and Their Johns, a Beban Kidron film about prostitution in New York City; No Sense of Crime, Julie Jacobs' film about women involved with men on Death Row; Kitty for Mike Barker, about a circus performer; and Reverse Angle, directed by Wim Wenders. Rinzler intends to continue work in documentaries as well as features. "It is an entrance and education into lives that I otherwise would not have access to," she explains.

After photographing several music videos for Tamara Davis, Rinzler shot the director's first feature, Guncrazy, a contemporary film noir effort starring Drew Barrymore. The film's evocative color and moody, atmospheric lighting help tell the story of an ill-fated young woman.

The cinematographer also photographed Nancy Savoca's first film, True Love, which uses lush saturated hues and naturalistic light to depict the travails of an Italian/American courtship.

Rinzler met Albert and Allen Hughes through her association with Davis. The brothers saw Rinzler's reel, which included rap videos shot for Davis and a black-and-white White Diamonds perfume spot starring Elizabeth Taylor, the latter offering a film noir look with a touch of James Bond elegance. In turn, Rinzler saw The Drive-by, a Super 8 film the Hughes brothers had made together. "It was brilliant," Rinzler recalls. "I just loved the roughness and economy with which it was shot. It was very to the point and I liked the subject because I was working on a lot of rap videos and had been around young black culture, so my eyes and ears were open. I was pulled in by the cleverness with which it was done."

The trio met and Rinzler expressed her admiration for The Drive-by, offering the brothers, "If you ever want to do a Super 8 film, I'll shoot it for you, and if you don't have the money, don't worry about it." Within months, Rinzler received a call that the two had the green light to shoot their first 35mm feature, Menace II Society.

That film began the unique collaboration between the directing duo and Rinzler, which now includes two features and a music video about Marvin Gaye. Rinzler stresses that Allen and Albert direct their films together. "They are a team," she says. "The way the brothers divide it up is that Allen works with the actors and Albert works with me in terms of the camera and the lighting. It's not like Allen would say to Albert, 'I want this actor, that's it!' They discuss, and they agree or disagree, and then they work it out. But they have their areas of focus and that makes it smooth enough for two people to be at the helm. They overlap in terms of having say. They are both directors."

During the two-year span between the release of Menace II Society and Dead Presidents, Rinzler maintained a steady dialogue with the brothers. "Albert and I kept up a big fax relationship: 'Look at this, look at that,"' she explains.

On Dead Presidents, Albert and Allen conferred about the look of the film, while Rinzler and Albert worked together planning and visualizing it. "We made up a shot list, and then two storyboard artists did sketches. Albert and I did an immense amount of preparation," she states. "By the time we got to the set we were pretty much just grunting at one another, nipping and tucking the camera operating and the lighting. There was very little conceptual discussion. Prep is essential."

Looking for period influences during the preproduction period, the filmmakers screened many "blaxploitation" films of the Seventies, such as Superfly, The Mack and Shaft. Rinzler also showed the brothers still photographs to communicate visual style. "It was a quick way to see the lighting and framing in something," she says. Another inspiration was Midnight Cowboy, directed by John Schlesinger and photographed by Adam Holender, ASC. Rinzler recalls, "I was grateful to find out that they also loved Midnight Cowboy, because I was wondering, 'Will a pair of 22-year-old young men relate to this film?' I was really relieved and excited to find out that they did, because to me it was emotionally and visually a synchronous experience."

In fact, Allen and Albert Hughes are rabid cinephiles whose key influences include Martin Scorsese's Taxi Driver and GoodFellas, as well as the films of Sergio Leone. "They love the framing of those two directors," Rinzler notes. "We really referenced them a lot on Dead Presidents."

Dead Presidents is set between 1968 to 1972, beginning as Anthony Curtis, a young middle-class black man played by Larenz Tate (who debuted as O-Dog in Menace II Society) goes off to Vietnam instead of college. When he returns to America, his country is not waiting with open arms. Curtis' reentry is rocky and he and his friends see only one way out: they plot to acquire cold hard cash — which they dub "dead presidents," in reference to the deceased commanders-in-chief on different denominations of bills — by any means necessary.

The visual design of the film was structured around the changes in the characters' lives. "It was like a three-act experience," Rinzler explains. "The scenes before Vietnam are brighter, more saturated and hopeful, with more sun. Vietnam is hot, frenetic, urgent and confusing. Once we come back to America, the look is colder, drabber, more dangerous and mysterious, with more darkness."

As in Menace II Society, Dead Presidents is filled with camera movement that expresses the anxieties and emotions of the characters. Rinzler strove to combine techniques to suit the requirements of various scenes. "There was always a lot of movement in the film," Rinzler says. "You're dealing with a young character who moves a lot. He was meant to be about 18, so there's a lot of energy going on.

"For a scene in a pool room earlier in the film, we had a fairly big shot and we wanted to shoot it handheld, but I thought it might be too rocky in the location. But Dennis Gamiello, the key grip, made a little speed-rail cart, and the operator handheld the camera on the cart; we got the best of both worlds without calling attention to ourselves."

Steadicam work was used "judiciously and sparingly" on Dead Presidents. "In the Vietnam sequence, we used a lot of handheld and a lot of handheld on a dolly. We didn't use any Steadicam at all," Rinzler explains. "In other parts of the film we used Steadicam because it was appropriate. There are times [in today's films] where it's really right, and times where it's overused. It has become a very accessible tool, but I think it will find its place the way zooms have."

The challenge of lighting Dead Presidents was in "using light to help the psychology of the mood come across," Rinzler comments. "We wanted to have the film to feel both natural and somewhat dark at the same time." For a scene in a church, Rinzler effectively matched her lighting style to the dramatic elements in the script. "In the scene, a preacher is asked to join in on a heist," she explains, "so we agreed it was appropriate to go for the master shot in silhouette, and I do mean silhouette — there was no light on the faces in this shot. In the close-ups, of course, Albert and Allen wanted to have enough light to see the faces."

During the production of Menace II Society, studio executives had intimated that the dailies were too dark, but the brothers fought for the look they believed in. "It wasn't a bright world that we were filming," Rinzler states. "The Hughes brothers are great protectors and allies. They said, 'Just keep going.' They're very strong in their own vision. They listen to their own inner guidance. I run the lighting ideas by them, and I run the colors by them. I show them gels. I also run the style and filtration by them. We haven't had any real lighting battles. Sometimes we go at it over camera style — what I think, what they think.

"Dead Presidents was predominantly a tungsten film, lit almost entirely with directional bounce light, thereby creating contrast; we flagged everything carefully to keep the light from going where we didn't want it to go, and to make sure it went where it was meant to. The approach was intended to heighten the viewer's sense of reality in a natural, non-obtrusive way."

In comparison to Menace, "We used much less smoke on Dead Presidents, almost none," Rinzler adds. "Smoke is a real tell-tale lighting diagram for the viewer. On a good film, you shouldn't be watching the lighting. The goal on Dead Presidents was to be seamless, to be organic in the camera design and the lighting, and to be somewhat understated. I felt it was very important to achieve the right balance of style and realism. You're not just recording on film; the idea is to express a story and the mood of the characters without calling too much attention to the technique. Some of the most beautiful images in movies, still photography and paintings speak in a quiet way. Loud stripes of light can be appropriate, but often they are imposed. Quiet photography is something to work toward and be comfortable with. As a cinematographer you don't have to say, 'Okay, look at me, I did this.'"

Rinzler was expressive with color when the story lent itself to an interpretive approach. "There is a character called Skip who dies of an overdose," she remarks. "As soon as I read that scene I thought, 'Green is a good color for death by overdose/ and I asked the production designer David Brisbin, 'Could you give me a green lamp?' It had an oval, light-green shade, so we spent a lot of time gelling it darker. That lamp motivated the use of green light.

"We always tried to work with light that was appropriate to the story. There is another scene in which people are planning the heist at a table and they lean in and out of light. The brothers had seen Asphalt Jungle, and they came to me and said, 'We want people to lean in and out of sharp cuts of light.' So we worked with a raw 2K bulb, which is very rough on faces. There was no diffusion on the bulb and no diffusion on the lens. The characters had eye sockets depending on how steeply overhead the light was placed. It was not pretty, but it's not meant to be pretty."

When Tony is arrested and taken off to jail, his sadness is illustrated in his reflection on the window of a prison bus. The scene developed during a ride back from a location scout. Rinzler explains, "We planned to make a series of shots of shackled feet and move up to faces. Dennis Gamiello said, 'Why don't we just do it as an overhead shot?' Albert's ears perked up, and he said, 'Yeah, that would look great!' The top of the bus was literally cut off as if with a can opener, and the bus was parked in a studio. We shot the reflection on location first, saw the dailies and picked which lighting we had to match. The gaffer, Bill O'Leary, set up a bank of 10Ks on one side and nine lights on another. Two electricians ran through the 10Ks with wooden, jerry-rigged items simulating trees so that a moving, broken-up light would go by. A truss bridge was built over the top of the bus that dollied down over the top and to the side at the same time. So this overhead shot that started as a 'what if by Dennis appears to be a simple, unnoticeable shot, yet it took immense time, planning and preparation."

Dead Presidents was Rinzler's first union film. She largely credits the crew with the success of the production. "I was truly blessed," she acknowledges. "Bill O'Leary, the gaffer, works pretty exclusively with Roger Deakins [ASC, BSC], and Dennis Gamiello is a terrific key grip. My biggest desire on Dead Presidents was a softer but contrasty light, and Bill had worked in that style a lot. He had worked on The Hudsucker Proxy with Deakins and the Coen brothers, and on The Shawshank Redemption. Dennis had key-gripped for Scorsese on The Age of Innocence, and for the Coens on Raising Arizona. They both had really been around the block, yet they were very spirited and enthusiastic. It was exciting for me to have that kind of support and collaboration. Dennis was extraordinary at rigging and he had the tightest bunch of grips — rigging grip John Lowry and dolly grip Eddie Lowry — who were skillful, delightful people. The best boy, Bill Moore, was a mastermind at creating little light rigs, like lights on chasers for car rigs. Rigging gaffer Richie Ford also had done huge movies and he could really advance and pre-rig a set. The rigging grip, John Lowry, did great pre-rigs. The camera scenic, Rochelle Edleson, was amazing as well: she could age down a wall within seconds if something was too white or too new. On any film, there's huge pressure, and you need every operation to be as smooth as possible."

Rinzler also had high praise for first assistant Alec Boehme. "Alec was great. It was a hard job for camera. There was a lot of violence in the script. Whenever there's violence, it means multiple-camera coverage. We were working at low fstops, which made for difficult focus-pulling."

On Dead Presidents, Rinzler made the transition from running the camera herself to working with an operator. "It was very hard for me not to do the operating," she concedes, "because I can see things more clearly through the camera. The operator has to sort of step aside during the lighting process. As soon as I could I gave the camera to John Sosenko, the camera operator, to practice the moves, but in terms of the lighting, I really need to see it through the frame. I'm not comfortable working with a video monitor. A lot of times during the actual takes I stood at the camera. I would watch a take or two on the monitor for the operating, and I was very specific with John. Backgrounds are important: they are a quiet psychology. It made all the difference whether someone was framed by just a wall behind them, or to move over three inches so you could see the depth of a corridor or the narrow depth of a bar in the background. I would watch the monitor enough to be assured that I was getting what I wanted in the operating, but I also stood by the camera to watch the actors in the light."

Rinzler selected 5298 stock for the interiors and 5293 for exteriors. "We basically used only two stocks. I had toyed with using 5245 for the more bright and cheerful saturated scenes, because it's fine-grained and lovely, but daylight was fleeting because we were shooting in the fall. Our day went from 7:30 to 4:00, and then bam! — the light was done. So we used 5293, which is contrasty, and 5298. We shot Dead Presidents in Super 35mm, and I didn't want to use 5298 for the interiors. I started with 5293, but its 200 ASA rating meant more lights and more crew people, so we wound up going to 5298 because we could use a little less light and have a bit more f-stop.

"We tested a lot of filtration, which I later threw in the garbage," she reveals. "We used the lightest Black ProMist — this was almost a non-filtered film. We worked with Don Donigi and Steve Blakely at DuArt for the dailies. Don oversaw the timing, and he's really an unsung hero. The man is a great synthesis: he knows technique and he knows what people want. I did lighting, contrast and filter tests and asked him to leave the filtration in. Then I asked him to time it out. From seeing the tests, he got a sense of what we were after, and he became a great aesthetic ally. If you're pleased with your dailies, you want your answer print to look like a good set of dailies; they are very critical."

Dead Presidents was shot with Panavision cameras, and Rinzler found the Primo lenses effective for working in Super 35mm. "The Primos are great sharp lenses and they're very good on flare," she states. "For a Super 35mm blowup, you don't want flare and you don't want it soft. I found that longer lenses were better in Super 35mm. A 35mm became the normal lens. The backgrounds become far off in a hurry when you use a wide lens, so a little bit longer lens is good. A 75mm is great for a closeup."

Studio work was accomplished on two stages at Empire Stages in Queens, New York. Production designer David Brisbin worked very closely with Rinzler in designing colors to accommodate the lighting style. "David did a great job on the sets," Rinzler enthuses. "He had a great scenic crew and a great art director, Ken Flardy. His tour de force was the pool hall set. It was really beautiful; it felt old and lived-in. It was a russet orange color with checkered linoleum. David and I discussed the ceilings at length. He wanted a tin patterned ceiling, and I felt we had to have some removable pieces and some beams to hide lights that would occasionally get placed up there. He was very attached to this tin-patterned ceiling, though. While doing some research, he found a pool hall that had a tin patterned ceiling with ducts, so we both got to have our cake and eat it: we used the tin patterned ceiling, and we hid the lights behind the ducts."

Rinzler's list of favorite films is a varied one. She admires the urgency of Mean Streets and Midnight Cowboy, and calls Raging Bull a "synthesis of camera and story." Other films that have left an indelible mark on her are Rainer Fassbinder's masterwork Berlin Alexanderplatz; John Huston's Fat City (photographed by Conrad Hall, ASC), and Wim Wenders' Wings of Desire, Alice in the Cities and An American Friend. (Rinzler collaborated with Wenders when she shot Lisbon's Story before principal photography began on Dead Presidents.) The French Connection, photographed by Owen Roizman, ASC, was an early influence that had resonance on Dead Presidents: "It's not a 'beautiful film,'" Rinzler points out, "but the camera style is a perfect fit with the story. It's gritty and raw. I'm very into being appropriate to the subject matter. I don't want every film to look the same. I want the material to determine the look."

Rinzler's vision of her future includes pursuing projects that she responds to — documentary or feature films that serve a purpose: "I want to stand behind the material and be proud to have my name on it."