THX 1138: Made in San Francisco

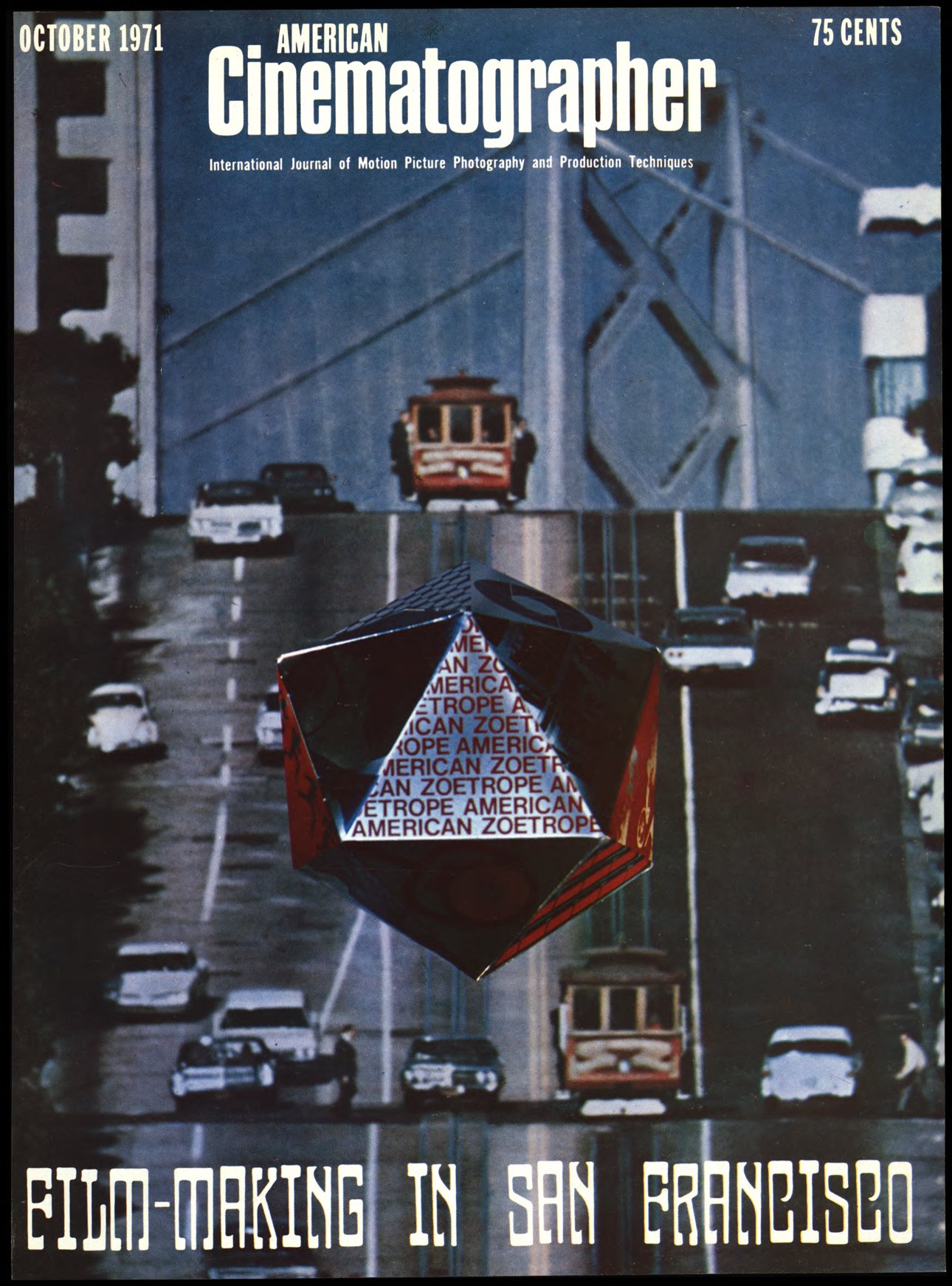

A group of young filmmakers from American Zoetrope, most of whom had never worked on a feature, turn cameras toward a chilling “Brave New World” vision of the future.

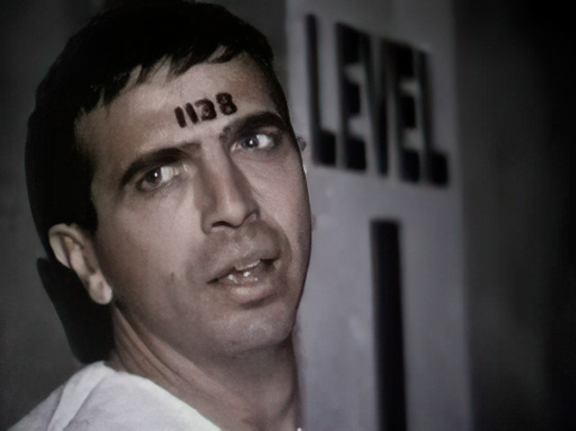

Warner Bros.’ THX 1138 is a mind-bending look into a future century and into a civilization that exists totally underground, its hairless citizens computer-controlled, euphoric with compulsory drugs and having arrived at the ultimate in human conformity under a robot police force.

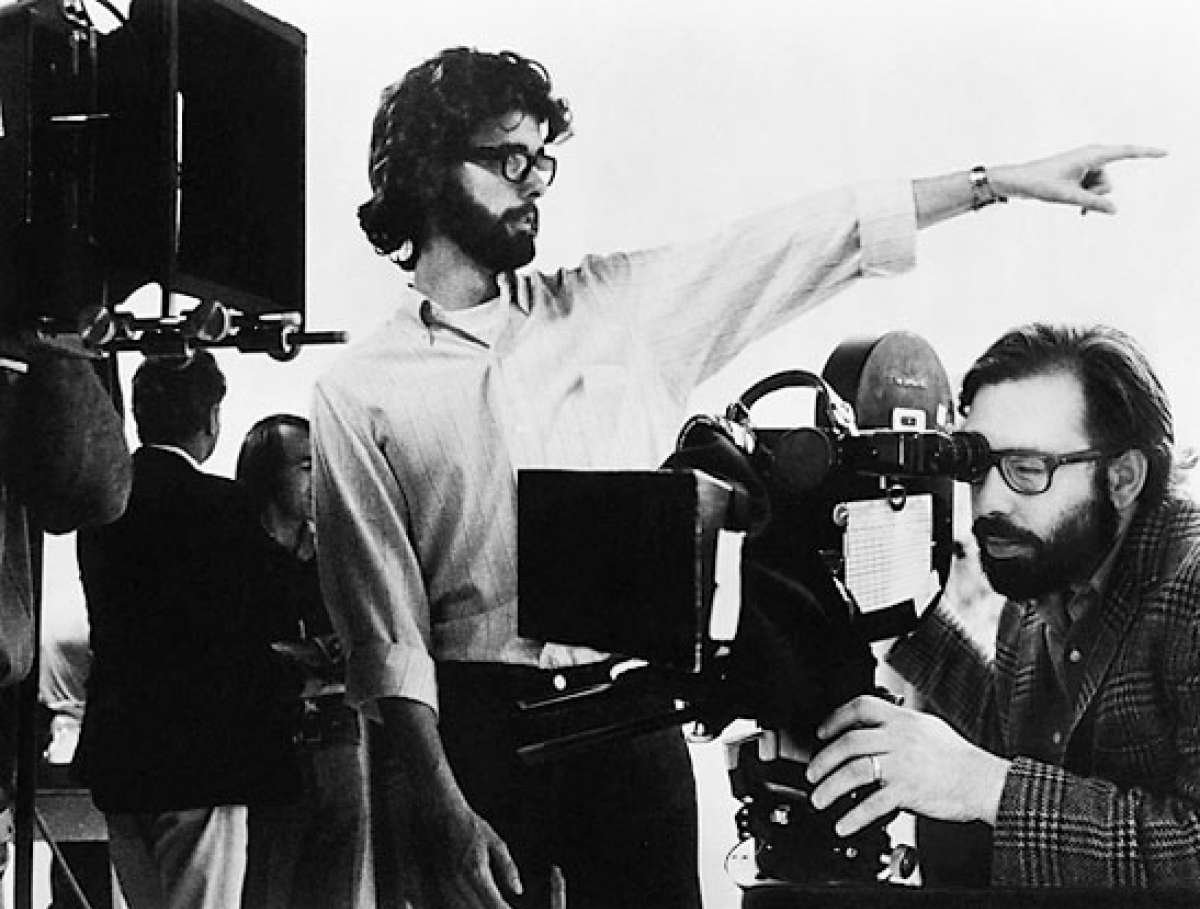

The American Zoetrope production for Warner Bros, release was directed by 25-year-old George Lucas, produced by Lawrence Sturhahn and written by George Lucas and Walter Murch. Francis Ford Coppola, head of American Zoetrope, was the executive producer. The film editor was George Lucas, the art director Michael Haller and the cameramen were Albert Kihn and David Meyers.

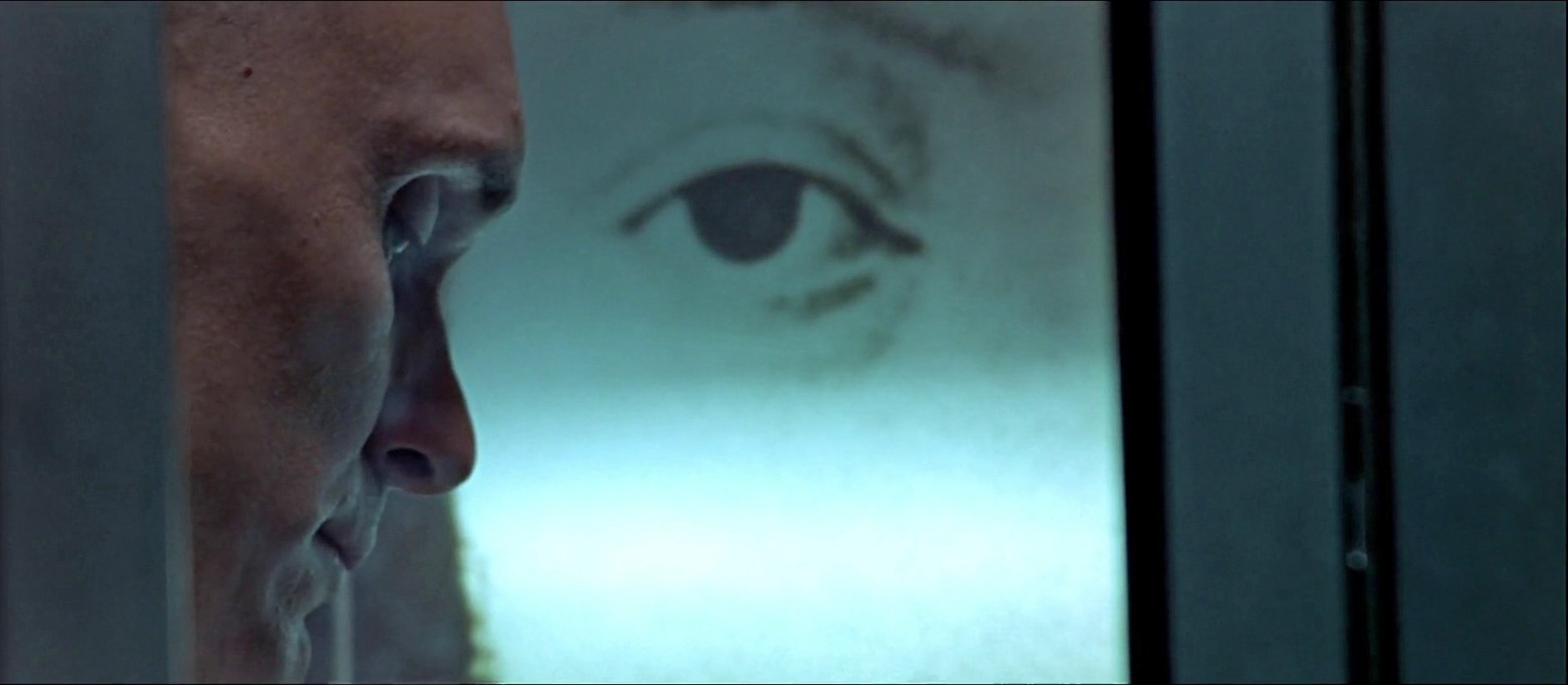

The story is concerned with the efforts of Robert Duvall, who plays THX 1138 in a society where a prefix and a number suffice for a name, to escape his drug-induced state, which leads to love, an unknown and even forbidden emotion in his dehumanized surroundings, and finally his attempt to escape completely from the subterranean world itself.

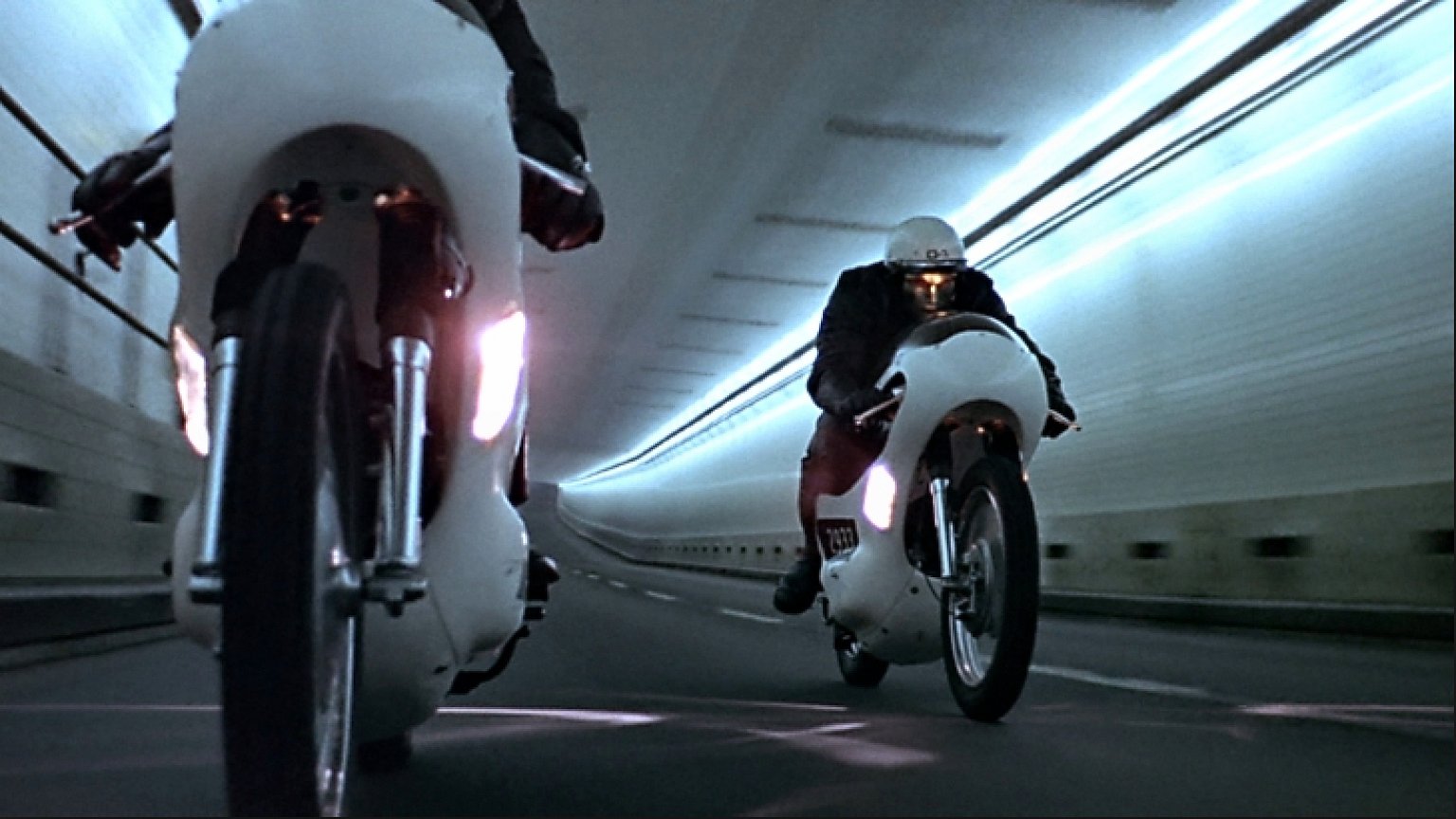

The THX 1138 company traveled to no less than 22 locations in the San Francisco Bay area, filming in such places as the Oakland Coliseum, the San Francisco Pacific Gas and Electric Building, the Marin County Civic Center in San Rafael and the various tunnels and tubes of the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) system, scheduled to go into operation in 1972.

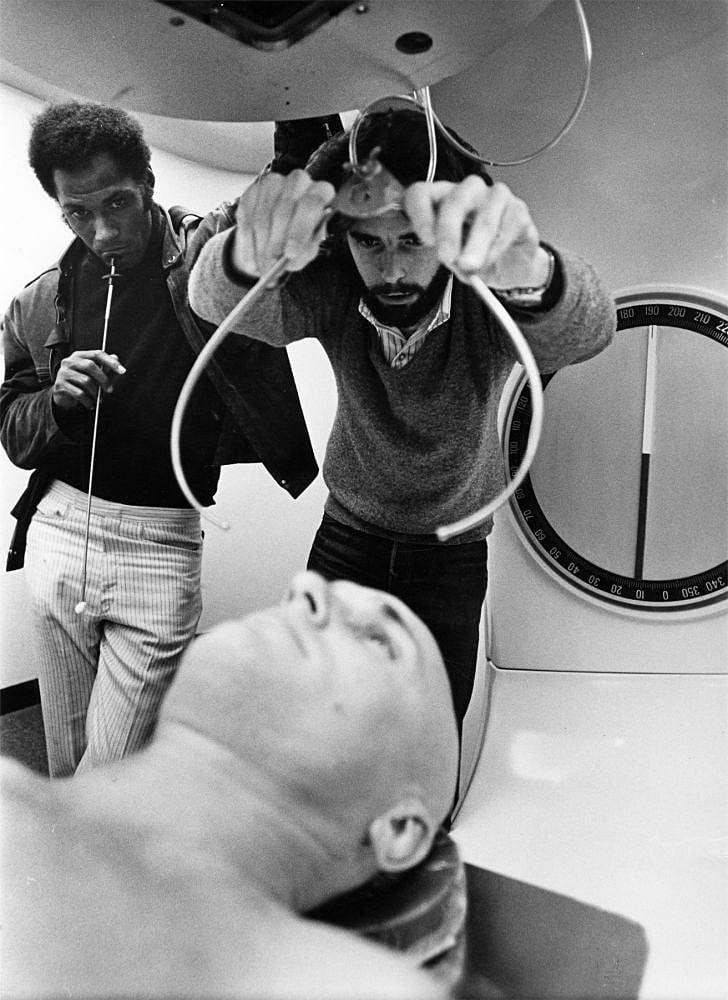

One of the chilling scenes shows Robert Duvall undergoing a medical examination of the future. To simulate this, director Lucas moved the company to a tumor research center in San Jose, where a four-million-volt linear accelerator and a laser treatment machine provided the necessary appearance of the medical machines of centuries hence.

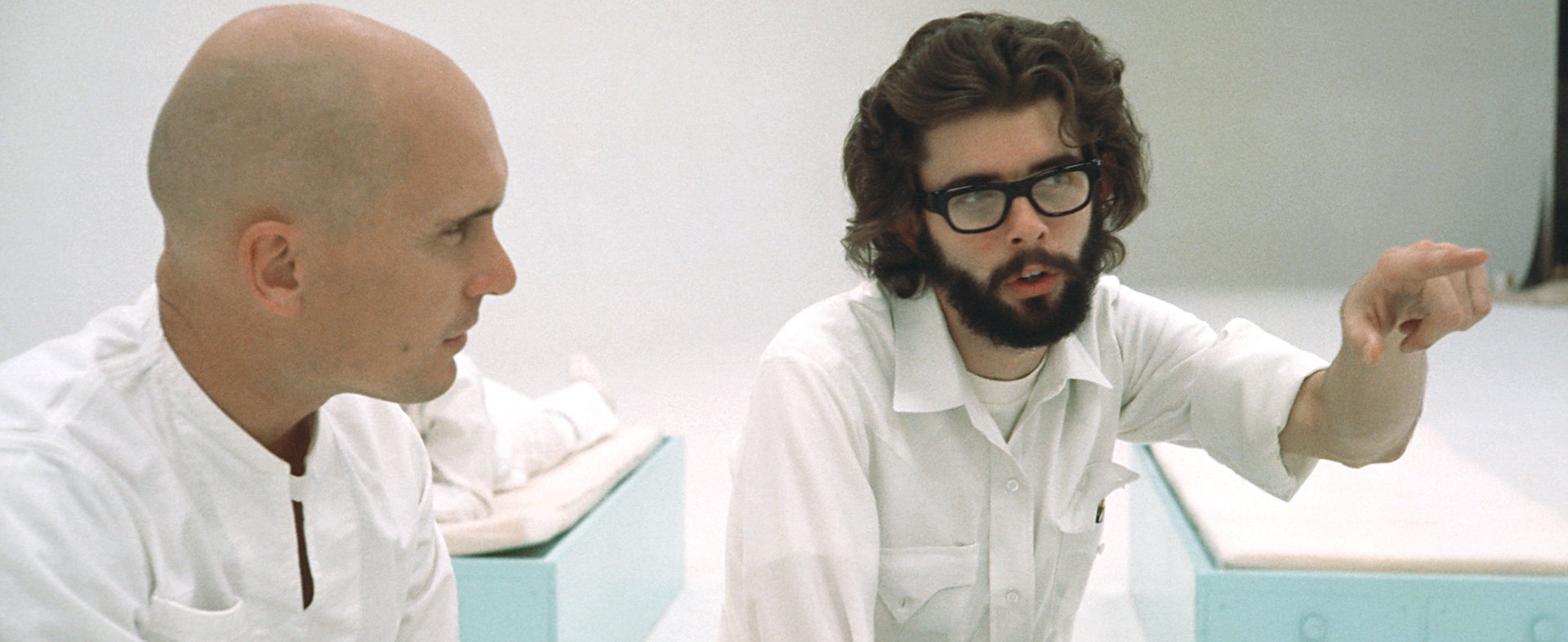

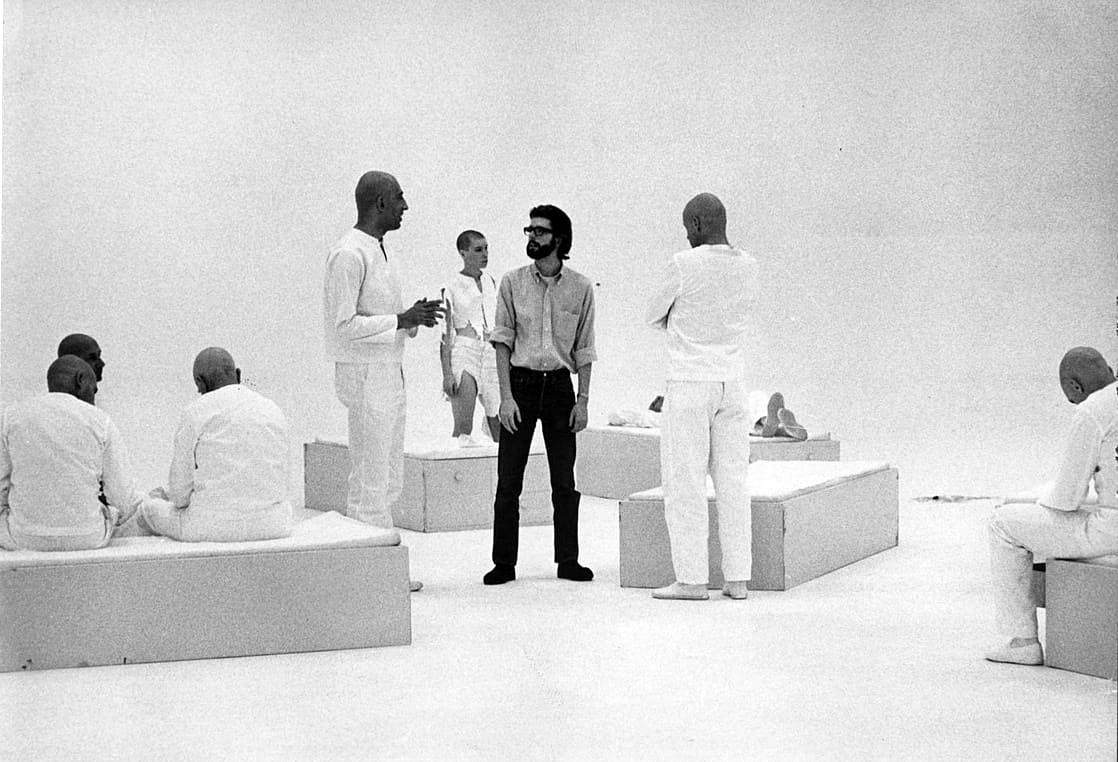

The THX 1138 company left the San Francisco area for one week to film a sequence involving a stark prison of the future without walls. The set, best described as absolute whiteness in all directions, served as a futuristic confinement facility without borders or boundaries.

Director George Lucas grew up in Modesto, Calif., and became interested in films while attending the University of Southern California. THX 1138 is his first feature picture, either as a writer or director, but it is based on a short he made while at USC which took the grand prize at the National Student Film Festival. Lucas has several other films planned for American Zoetrope production. Francis Ford Coppola, the executive producer and creator of American Zoetrope, is only 30 but has had a decade of experience in motion pictures, much of it as a writer. He attended Hofstra University in New York before going to UCLA for his master's degree in filmmaking, where he won first prize in the 1962 Samuel Goldwyn writing competition. He made his professional debut in 1967 as writer and director on the highly acclaimed You’re a Big Boy Now, then directed Warners' Finian’s Rainbow and wrote and directed The Rain People for the same studio. It was while he was in the post-production phases on that film that he realized his "ultimate dream" with the founding of American Zoetrope and its ultra-modern film facility in San Francisco. Coppola won an Academy "Oscar" last year for his screenplay of Patton. He has recently completed co-scripting and direction chores on Paramount's The Godfather and is currently in the process of editing the picture at Zoetrope.

The production of THX 1138 was unique in several significant respects, among which were the following:

(1) Though financed and released by Warner Bros., the film, in its creative concept and execution, was in no way a "major studio production"; on the contrary, it was totally the product of American Zoetrope, the San Francisco-based filmmaking "commune," founded and funded by Francis Ford Coppola for the purpose of attracting, encouraging and utilizing talented young film technicians new to the industry.

(2) Except for a couple of short sequences requiring set elements that did not exist locally, the picture was produced, photographed and completed entirely in San Francisco, with postproduction utilizing the highly sophisticated technical facilities of American Zoetrope.

(3) Only one small "set" (an austere apartment of the future) was actually built for the production. Enormous production value and an atmosphere of great scope were achieved by utilizing carefully selected structures and locations existing in the San Francisco area.

(4) THX 1138 was made by a relatively small crew of primarily young technicians, most of whom had never before worked on a feature film.

(5) The picture, filmed in Techniscope, is highly stylized in its photographic treatment. A distinctive visual aura, perfectly adapted to the subject matter, was achieved by breaking established photographic rules — not haphazardly, but with a high degree of skill and control.

Following are the accounts of several key technicians relating to their respective functions in the production:

THE CONCEPT OF THX 1138

By GEORGE LUCAS

Co-writer/Director

My primary concept in approaching the production of THX 1138 was to make a kind of cinema verite film of the future — something that would look like a documentary crew had made a film about some character in a time yet to come.

However, I wanted it to look like a very slick, studied documentary in terms of technique. I come from a background of graphics, photography, art and painting — and I'm very graphics-conscious. So, I don't believe that a documentary has to look bad because it follows a cinema verite style. It can look good and still look real. Simply stated, that was my approach to every element of the production — the sets, the actors, the wardrobe, everything.

At the same time that I wanted the picture to look slick and professional, in terms of cinematic technique, I felt that the realism of the film's content would be enhanced by having the actors and their surroundings look slightly scruffy, even a little bit dirty, as they might well look in the society depicted. They wore no makeup, which helped to keep them from appearing too slick and clean.

I had in mind a certain "honest" look for the film, which I felt could best be achieved by using documentary cameramen. However, the main approach would be in the lighting. The idea was to not light anything unless it was absolutely necessary. Only if we walked into an area where there was no light at all would we put up a few low-wattage lights here and there. Otherwise, we would just let everything go the way it really was.

Another graphics concept in the film would be very flat lighting, with everything quite two-dimensional. Aside from its stylistic value, I knew that the no-lighting approach would enable us to move very fast in shooting. Obviously, we would have to do something to compensate for the lack of light, and that led to our decision to force-develop practically the entire film. We decided to "push" everything, except for the shots to be used for making opticals. By not pushing those shots, we hoped to achieve a consistency of graininess throughout the film.

I was well aware that there would be those in the audience who would be shocked by the graininess at first, but I was sure that after the first minute or two they would get used to the grain and simply accept it as part of the stylistic concept, the documentary approach.

As I said, I felt that THX should be photographed by someone with a very thorough documentary background, someone who was used to thinking fast and making quick technical decisions — also someone who had a feel for riding focus on unrehearsed action, without having to measure things off.

When production-planning first began on THX, I was living in Los Angeles. Haskell Wexler, ASC, is an old friend of mine from the time when I was going to school at USC. He's a great guy and a real friend of the student. While I was writing the script in L.A. I asked him if he would be interested in photographing the picture and he said that he would be. But by the time we were ready to go into production, I had moved up to San Francisco with American Zoetrope and, because we were a San Francisco company, the decision was made to use only San Francisco technicians.

Later, when we came down to Hollywood on location, Haskell was our standby cameraman. He did some of the shooting (three Directors of Photography, no less!) and helped us out of some of the tight situations that can break you on a low-budget feature. He was always there when we needed advice.

As for our two full-time Directors of Photography, both of whom live in San Francisco — Al Kihn had worked as a TV newsreel cameraman for four or five years and had shot a few documentaries for the USIA. Dave Meyers, who is older than Al, has had a great deal of experience and is highly respected in San Francisco as a documentary cameraman. He shot many of those fine documentary sequences in Woodstock.

We talked to every cameraman in San Francisco and looked at their film. We selected these two primarily because I liked the way they "thought" on the screen and the way they followed the action. They were both obviously good technicians who knew how to make the best of a situation. These things are important because it's tough doing a documentary. It's a real exercise.

As an example of what I mean, when we got into the actual shooting, I would set up a scene and rehearse it maybe once. A lot of the time I didn't rehearse at all. There were no marks and no measurements. The cameramen just had to guess where the actors were, while riding focus blind in a lot of cases. We were shooting at such low light levels and with such a shallow depth of field that it was very hard to keep things in focus, but they did an excellent job. Very often we'd get it in one take, and I almost never shot more than three takes on a scene. This was due mostly to the fact that I had a very professional cast of excellent actors.

If a take was acceptable, but not perfect, I would move the cameras before doing it over, instead of making take after take from the same positions. This gave me a vast number of different angles for each scene. Since I planned to edit the picture myself, I wanted to be able to "make" the film in the editing. The shooting was designed for me to end up with a lot of documentary coverage so that, hopefully, I would be able to cut together a perfect performance in every case.

I got so that I knew which actors gave their best on the first take and which ones needed a couple of takes to warm up. We would zero in on their closeups accordingly, using long lenses, so that the actors literally never knew when they were being filmed in closeup. This resulted in more natural performances, because they were playing to each other all the time (instead of to the camera) and they didn't get uptight, as actors often do when they know they're in a closeup.

While we shot with available light almost exclusively, this wasn't always as difficult as it sounds. We were shooting mostly modern interiors, which usually have 10 times more light than they really need. It's just an architectural phenomenon of the 1960s and ’70s to way over-light interiors.

However, sometimes we'd walk into places where it was so dark that we'd have to turn on a flashlight just to read the needle on the exposure meter. Very often the meter didn't indicate any reading at all, but we didn't let that stop us. Our pet phrase during the entire shooting was: "Just put on your fastest lens, open it up all the way and shoot."

Despite all that, we kept getting back dailies that looked good. Everyone kept saying: "Gee, I never thought we'd get that one." But as long as it kept coming out all right, we kept doing it. We always ordered one-light dailies — never a timed print — and, incredibly enough, almost the entire picture printed on light 12.

I wanted to shoot THX in a widescreen format because it is, basically, an environmental film and I felt it was essential to get it as big as possible. I chose Techniscope over the available 35mm anamorphic processes because we could use faster lenses and our Eclair cameras could easily be switched over to the Techniscope format. Also, while the Eclairs normally carry 400' magazines (which are awkward for the shooting of a feature), the Techniscope format gave us the equivalent of an 800' load of straight 35mm. I wasn't afraid of the blow-up involved, because I had shot a lot of 16mm that had been blown up to 35mm. To me, Techniscope is just another form of Super 16. Or maybe "Super-duper-16" is more like it.

There was one sequence in the picture that we went all out to light completely. That was the "cathedral" sequence near the end of the picture that was actually shot in a TV studio. They had all of these lights electronically controlled by push buttons so that we could do whatever we wanted in the way of lighting. We sort of ran amuck with back-lighting and everything else we could think of. It was a lot of fun, and it relieved the frustrations of the gaffer. It gave him a chance to actually light something.

No film ever ends up exactly as you would like it to, but, with minor exceptions, THX 1138 came out pretty much as I had visualized it, thanks to some excellent assistance — and a whole lot of luck.

SHOOTING THX 1138 WITH (ALMOST) NO LIGHT

By DAVE MEYERS

Co-director of Photography

There has been considerable comment that the photography in THX 1138 has a unique look to it, a distinctive texture. If so, that can be credited to George Lucas. George has a terrific sense of graphics. He knew what he wanted and it was, fundamentally, his style. It wasn't something I dreamed up or Al Kihn dreamed up. We collaborated with him in order to get it onto film, but I was personally very much impressed with his graphic sense. It resuled in a very interesting visual style.

We shot practically everything in the picture with two cameras. That's the way it was set up. They wanted two cameras operated by two people who could sort of wing it individually. I suppose that's why they hired documentary cameramen. George would tell Al and me what the scene was to be and we'd decide which lenses were to go onto the two cameras. Then each one of us would wing it through the scene on our own. Surprisingly, this method worked out very well.

We were tied down to using equipment owned by American Zoetrope. That included Eclair CM-3 cameras, which I'd never operated before. I knew that Haskell Wexler owns one and that he likes it — but he had also worked his over considerably. I was basically against using that particular camera because it is noisy and hard to blimp, but after a while I became quite fond of it. The basic camera is good, the finder is great, and it is fairly easy to adapt to the Techniscope format. Blimping was a problem, but we had a couple of blimps custom-made by Carroll Ballard, and they worked out quite well.

We used an Angenieux 25mm-to250mm zoom lens (T-stopped to 4.2) a very small percentage of the time. For most of the shooting we used a complement of Nikkor prime lenses ranging from 21mm to 300mm — the same lenses made for Nikon still cameras. They have remarkably sharp resolution, good color correction and are very consistent with each other. The only annoying characteristic is that the helix is exactly the opposite of that of the zoom lens. I would find myself instinctively flipping in one direction, but going completely the wrong way. It was very hard to get used to.

We used available light as much as possible in shooting the location interiors, working at as low a light level as was feasible in order to get the required effect. Often we'd go to a location and George would show us the action and the shot he wanted. I'd say to myself, "We're going to have to light this one." But then we'd get to figuring around and wind up using nothing but an edge light from behind a door or a small quartz light to pick up faces as the actors came through.

We did have the advantage of scouting most of the locations beforehand and making some tests. We knew we were going to be working on the ragged edge of the available light and it was mainly just a matter of getting used to working on the ragged edge. Like the sequences shot in the BART tunnels, for example — you'd swear you couldn't get an exposure, shooting it the way it was lighted, but by the time we got around to filming it we knew we could. They use something like mercury arc lights spaced about 50 yards apart along the sides of the tunnel, and we were able to set up a couple of 2000-watt quartz lamps to get a rim light and a bit of definition where it went completely black — but we shot sequences under conditions where you couldn't have gotten an exposure with a Leica at 1/10th of a second, using ASA 500 film. It was unbelievable.

That we were able to get it at all was mainly due to the fact that the effects George wanted, graphically, were the effects you normally get when shooting at an extremely low light level, with very little modification. In other words, he wasn't asking the impossible; he was simply exploiting aesthetically the low light level that existed. The same conditions could be exploited by other people, too — except that they don't have the aesthetic sensibility to visualize the effect—or they don't believe it can be done, especially if they come from a studio background. I do documentary filming most of the time and I'm used to shooting in places like the subway, so I knew what we could do. Plus the fact that we had 5254 negative to work with and the Technicolor lab processing it.

I don't think you can beat the Technicolor lab when it comes to consistent quality. I don't remember any dailies that were off. There was always that consistency of quality in the dailies.

In the prison sequence, George wanted to have the faces, and practically nothing else, show up against a stark white void — an extreme limbo effect. We shot this in the studio against a huge white cyclorama, with every skypan we could get mounted overhead. Even though the corners of the eye were rounded, there was still slight definition in the background, so we poured more light into the corners.

It was my educated guess that, in order to get the flat white void George wanted, we would have to overexpose the sequence by about two and a half stops. We made some tests, bracketing with various exposures, and it turned out just that way. In the actual filming, the set was lighted for F/11, and we shot it just cracked open from F/5.6. The natural reflective quality of the white eye added almost 1/2-stop more of exposure. I believe we pushed it a bit, too, in the processing, just to add to the unreal effect.

Shooting that sequence was a real challenge — trying to follow-focus with a 200mm lens on actors coming from deep background up into closeup, with nothing but the face floating against that limbo white. It's a sort of freakout. You feel as though you're going blind. A couple of times I stopped shooting because I thought I'd lost the focus completely, even though I still had it—everything had simply turned into a blur.

We shot a sequence in the BART headquarters control room, before it went into operation. We hit them just at the right time, because we could never get in there again. It had this fantastic control panel and looked like a million-dollar set. There was fluorescent overhead lighting. We made some pretty careful tests in there — lighting it completely, augmenting it with both tungsten and daylight-compensated light, then shooting it with the existing light plus some gel corrections. The absolute optimum combination for the effect we wanted would have been — as it turned out — the existing light plus something like an 85A filter, but it was so slight a correction that it wasn't worth the trouble, and we just shot it straight.

We had some interesting experiences shooting the sequences where the robot police, on motorcycles, chase Duvall's car through the tunnels at high speed. I guess some people might think this was done by means of trick photography or special effects, but the car chase was actually very straightforward. The only gimmick was that we did some of the closeups with both the camera and the car mounted on a trailer.

However, the rest of it was for real — as I found out when photographing it. I started out by shooting from the camera car. Then I made it into the racing car and got some shots while roaring through the tunnel at 140 miles per hour. Feeling kind of brave by then, I said to myself: "I'm really getting in there now — so I'll just try that motorcycle.”

They had a low-bed racing sidecar on one of the motorcyles — which was the loudest, meanest-sounding machine I'd ever heard. They sat me on the sidecar with the camera tied down on a high-hat about two inches off the ground. That tunnel was two or three miles long, and the guy driving the motorcycle took off down it, accelerating all the way up the range. Every time he shifted gears, I thought he couldn't possibly accelerate any more or go any faster, but he kept going right on up from gear to gear, faster and faster. When he reached top speed (130 miles an hour, he told me later), the damned high-hat came loose and I started to slide off the back end. The noise was so deafening that I was actually in pain from it.

I was shooting sort of through the front wheel and for me it was like being projected into orbit. I just barely managed to hang on until we made it out the other end of the tunnel. Later, when I saw the scene on the screen, it all went by so fast and the walls were so uniform that it looked like some kind of process shot made in the studio. It didn't look like anything — but, man, what a trip!

PHOTOGRAPHING A FIRST FEATURE: THX 1138

By Albert Kihn

Co-Director of Photography

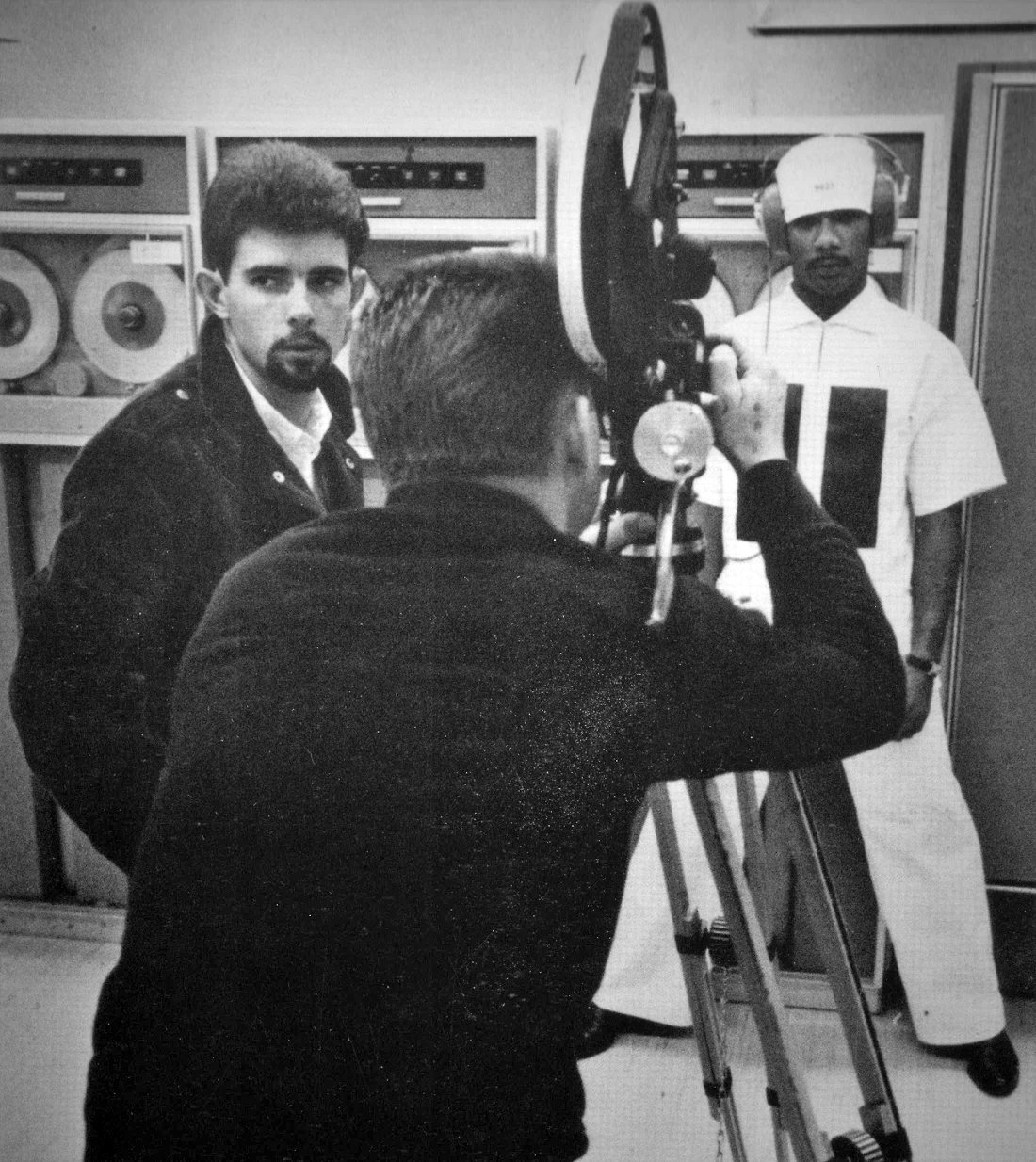

THX 1138 was not only the first feature I'd ever photographed (as it was, also, for Dave Meyers), but I'd only been freelancing for less than two years. Before that, I'd been doing news and documentary work exclusively, at a TV station in San Francisco — and their requirements were not awfully sophisticated, to say the least. I had also made some documentary and industrial films but they weren't too demanding either.

The major difficulty in switching from documentary to feature filming was getting used to the new experience of working with a sizable crew. It's a totally different world that you find yourself in. When you're doing a documentary, you work with a four-man crew — which is still rather large for that kind of operation. On THX 1138 we had 15 people, more or less, around all the time — a very small crew by Hollywood standards, but a lot more people than work on a documentary.

The size of the crew very definitely affects your working style. When you have a lot of technicians who have to be geared and synchronized to work together smoothly and comfortably on a project, it becomes a huge machine. So, to me, the crew size was the biggest change and, in a way, it was the biggest problem, too — trying to fit myself into it and see where it was going. Also, your human relationships are totally different from those of a documentary situation where you talk every day with a small group of people. George Lucas is, himself, a very talented photographer. This tended to take away some of my initiative, because George knew exactly what he wanted as a cameraman, as well as a director, and he was fully responsible for the photographic style of the film.

Before we started shooting, George had a wall full of stills, some of which he had taken, some of which Walter Murch had taken, and others simply clipped out of magazines, that represented pretty much the style of the film. For instance, George decided that, whenever possible, we would shoot the film with available light, capitalizing on the ugliness of blue and white and green fluorescence that just destroys the features of people and their humanity. This was exactly what George wanted and he let us know that was what he wanted.

Many people consider THX to be a work of graphic art. I'd say that a good part of that was George's doing. He felt that Dave's eye and mine saw somewhat like his, or as close as he would find in San Francisco. He was very specific in what he wanted in the way of framing.

One thing that applies to the whole film is that what gives it a lot of its quality are the rules that were broken. It was not the things that were taken advantage of, but the things that were not done that made the film. The people at Technicolor must have been tearing their hair out because this film with this strange light quality would be coming in to them. Whenever you read photographic magazines or Eastman's pamphlets on how to get good color, they tell you how to get this precise control of color quality. We did everything that would "uglify” the color. Instead of just putting on filters and searching desperately to find some way to counteract the available fluorescent lighting, we'd shoot it. If there were some sunlight spilling into it, we wouldn't correct it. We'd let it go blue.

That was all part of the format, which made it easier for us in the sense that we could use anything that was available and, therefore, take advantage of the fact that people walk around in a lot of ugly light. If you go and sit down in any restaurant you're in THX as you eat your donut and coffee.

Working with Dave Meyers was both easier for me and not easier. It was complex. For one thing, this type of film was a new project for me and I was glad there was another man like Dave there. That was a help to me, and yet it was complicated, too, because with two men you weren't quite sure who was doing what and it could get complicated. And then with two cameras you have the problem of having to make a sacrifice in the quality of your shot. Quite often I felt that there would be only one prime shot. We would be running two cameras and you would get one shot that wasn't what a cameraman would want. And yet, for George's purposes, it was right because he wasn't always after the prime shot or the fancy shot. He wanted a very restrained kind of thing where the camera would sacrifice polish to get, not only a documentary quality, but a quality of something almost automated.

As he told us before we started, he wanted it to look as though everything were being observed by hidden television cameras, such as those which would have been used in that underground society. And he did as much as he could to see that Dave and I didn't do the little fancy things that cameramen will do to polish things or to protect themselves with a little gimmickry. He wanted to take away those opportunities and that drive, and the two-camera thing helped him do that.

Like myself, most of the people on the picture actually had never worked on a feature before. Kenny Phelps, the gaffer, had, and a few of the others. Although I hadn't worked on a Hollywood feature before, I didn't feel that this constituted a problem. In fact, I had the feeling that this, being a new experience, by and large, for the crew was a good thing. It fit in with the fact that it was George's first feature directing experience, that it was all part of the Zoetrope scene of doing something new, and using new people. I never felt any strain in the crew due to their not having had a lot of experience in features, because they all functioned smoothly. Technically things got done and moved along quite well.

THX 1138 had very little handheld photography. We wanted the sense of the camera being anchored and having to struggle to get your shots with a heavy, automated machine. The cameras we used were Eclair CM3s. They are terribly noisy and, unfortunately, they had to go into blimps, which just "grounds” them. That was one thing I found most difficult about doing a feature, having to work with the camera in a blimp. I disliked it intensely because it insulates you from your camera and, if you're used to news and documentary work, your camera becomes part of you because you can handhold it. To then adapt to something that weighs as much as a blimped 35mm camera takes some time, and I'm still not comfortable with the blimp.

In the photography of the chase there were two spectacular car crashes. The photography of these scenes was always covered by two, and sometimes three, cameras. There were many occasions of all-night shooting in cold, damp places — exhausting, bleak places that affected the crew and put everybody down. It got really tiring. We'd go and spend the whole night, say, at the Caldecot tunnel, in order to get what would be just a few seconds or minutes of film for the chase. It had to be a combination of many tunnels to get the final effect, to capitalize on all of that available scenery.

In lighting all those tunnels — the Caldecot, the one going out to the Golden Gate Bridge, the tunnel going out to Fort Cronkhite, and the Broadway Tunnel — we used only available light. The only extra thing added was a little light Bill Maily put inside Bob Duvall's racing car. The racing car was on the truck bed and then the cameras, two cameras always, would be on the truck bed alongside the car. Sometimes we'd clamp onto the car with one of the really fine devices that Kenny Phelps had built.

The scene of the car and the motorcycle flying up was both planned and unplanned. The shot itself, as far as the accident was concerned, had been planned. The policeman was supposed to come zooming up and then be destroyed and the stunt man was going to take a fall there. However, he had not figured on taking the kind of fall that you see in the film. We had no idea he would fly so far. A little ramp was made in the dirt there, after the car had spun out, and when the stunt man came up, he was supposed to go into the dirt. Instead he flew that incredible distance into the car and the instant he hit the car we all stopped shooting. I remember one of the assistants leaping out of the car, because we had a third camera there, and he made a shot of the fellow flying through the air as seen from Bob Duvall's point of view. We were calling an ambulance, while that stunt man just lay on the ground on his back. Most of the fender of the car and the headlight were knocked off where he'd bashed into it. And then, a minute later, he opened his eyes and said, "How was that?'' We all got at him when he said, "Well, you wanted me to play dead, didn't you?" He got up and walked away. So that part was definitely not planned. It was incredible.

A lot of the film was pre-recorded. In other words, you see a lot of it on television screens in the next dimension back. Most of that was done with the 16mm Eclair and it was done more quickly. We knew it was to be the television monitor footage and so we didn't put quite as much effort into it, hoping we could save a little time. Often one of us would be shooting a 35mm scene while the other would be shooting with the 16mm Eclair. Sometimes we would both be working with the Eclair. There was quite a bit of footage that was to be seen on monitors and so the Eclair was there for that purpose.

The photographic procedure for shooting the television screens was very basic, almost exactly as you would do it in a documentary. There was no effort to counter any shutter bar effect and, as you know, cameramen will go to great lengths to get rid of those, as in The Andromeda Strain. They went to incredible lengths to eliminate them, because the monitored images were to play such a large part in that film. But we didn't; we let it go and found that we could get by quite acceptably for our purposes because it was to look almost like an amateurish kind of television-monitoring system. In the whole film, instead of a polished future of total technical control, it was a sloppy future of technical know-how in the hands of people who weren't quite complete. Things were sloppy, and so it fit in. It was to be part of their human environment; they have technology, but they're not so polished. Crude things happen in that technological environment, so all we did was take readings on the TV monitors and it called for our shooting pretty wide open. We'd shoot at F/2.8 roughly, or F/2, and with our film speed, we could handle that comfortably. So the lighting was very, very minimal in the control rooms. We filmed those sequences at KGO-TV and at KTLA in Los Angles.

The following short film — directed by Lucas — was released as part of the studio’s promotion for the project: