Walking Dead and Loving It (Part II of II)

Cinematographer Stephen Campbell details his visual approach to the apocalyptic horror drama The Walking Dead.

Director of photography Stephen Campbell — alternating episodes with Michael E. Satrazemis — is currently helping to shape the nightmare world of The Walking Dead, one of the most-watched scripted TV series on television, which boasts legions of fans worldwide.

Recent Walking Dead episodes that were shot by Campbell include “Go Getters,” “Swear” and the mid-season finale “Hearts Still Beating.”

The following is the second half of a lengthy discussion with Campbell that took place before a live audience during the 8th annual Downtown Film Festival in Los Angeles.

(Click here for Part I of this interview.)

American Cinematographer: [To audience] At this point in the discussion, does anybody have questions? Things you want to hear Stephen elaborate on?

Audience Member: You explained how film helps conceal blemishes and other imperfections that are more apparent in the high-definition of digital. I know a lot of people who shoot digitally for independent films — and students, of course — who will use filter effects in post to accomplish the same thing. Since the show is finished digitally, would it not simply be easier to do all of that in post?

Stephen Campbell: We do a huge amount of CGI work on the show and they will make cosmetic corrections after the fact. Often, it’s about erasing something. Or something may be too bright or too dark, which we can fix in color correction. But the interesting thing is that we shoot much of the show on Kodak [Vision3 500T] 7219, which is a 16mm tungsten-balanced film stock that’s rated at 500 ASA. We rate it at 400. But, in daylight, we don't shoot it with [standard 85] color correction. We shoot everything clean, without filters. Before telecine became so sophisticated, we used color-correction filters all the time. We had to correct the tungsten stock because they didn’t offer daylight-balanced stocks back in those days. So you would correct it accordingly while shooting. But, now, we don't use correction filters. Instead, we correct while doing the transfer.

We do this because it allows us to have a uniform base to work with. Maybe we want it to be not as warm or not as cool. So you're taking the raw image and saying, “Well, for this scene, we want it to be less cool than a complete correction would make it." This just leaves our options open for later on.

American Cinematographer: And it takes one more piece of glass out of the equation, because every layer of glass between the image and the film plane is another level of some microscopic distortion.

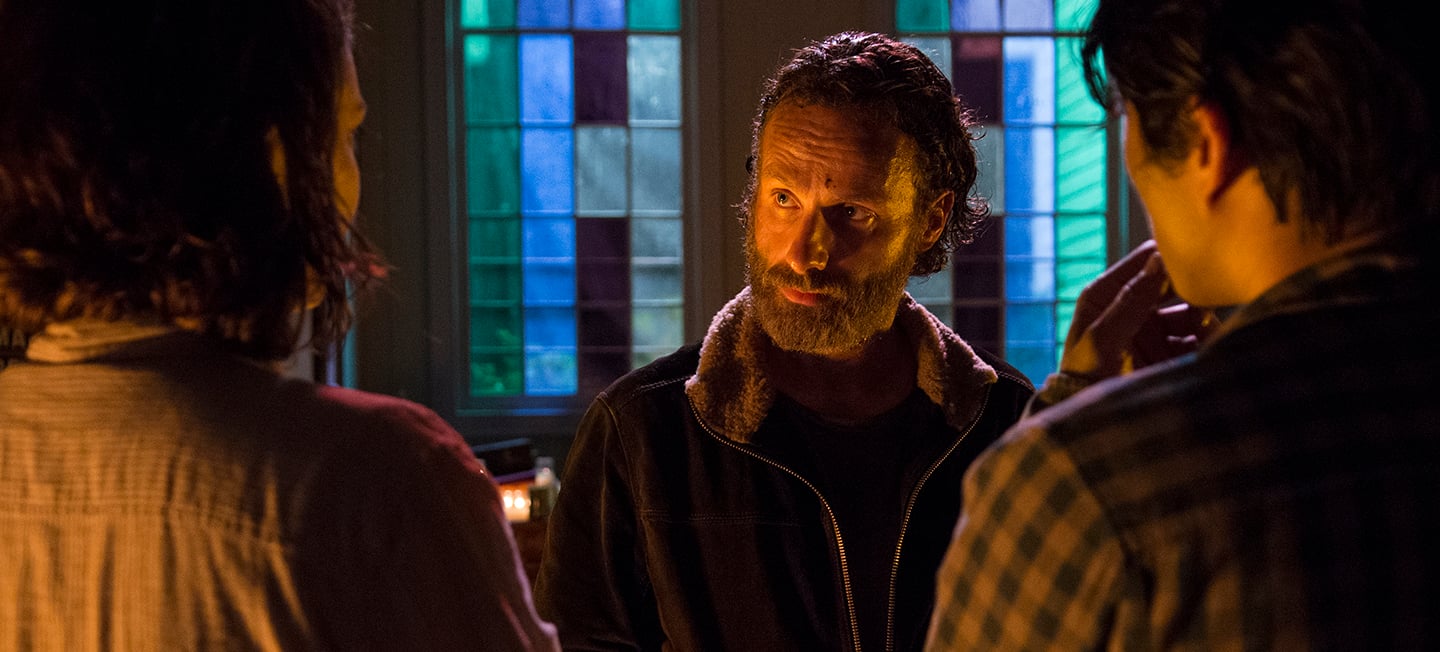

Totally. And we often shoot into the sun, just because we shoot a lot of low-angles. A lot of the show is shot from well below the actors’ eyeline, if you notice, because these are all comic book characters. So we call it “hero-ing them up.” For example, Rick [played by Andrew Lincoln] is never shot above his eyeline. He's always shot as low as we can go. Our favorite tool on the set is called a Lambda head, which allows the camera to work within inches of the ground and still move freely — we can put it on a dolly and track with it. So, that way, we can easily get those low angles on the cast. As a result, we're constantly shooting into the sky and into the sun. Not having additional glass of filters in there is probably the best. That said, we do use a lot of ND filters. Because the 7219 film is rated at 500, when you're outside, it’s way too sensitive. So we have to add a lot of ND filters to bring our stop down, because I usually try to shoot with the lens closer to wide open, which helps control the way you see the image by reducing the depth of field. That directs the audience’s eye to exactly what you want them to focus on.

This show has an amazing amount of digital postproduction. And, as a fan of the show myself, it's remarkable the way the practical makeup effects that Greg Nicotero and his crew put together are combined with digital effects, and how gruesome sometimes it can be. And we're actually going see a clip today one of the show’s most shocking death scenes, which you photographed.

Yeah. We'll watch that. You want to watch something now?

Yes, let’s do that

Okay, I brought three clips from three different episodes and we'll talk about each.

You spent quite a few episodes there in the church. Did you build the whole exterior and interior?

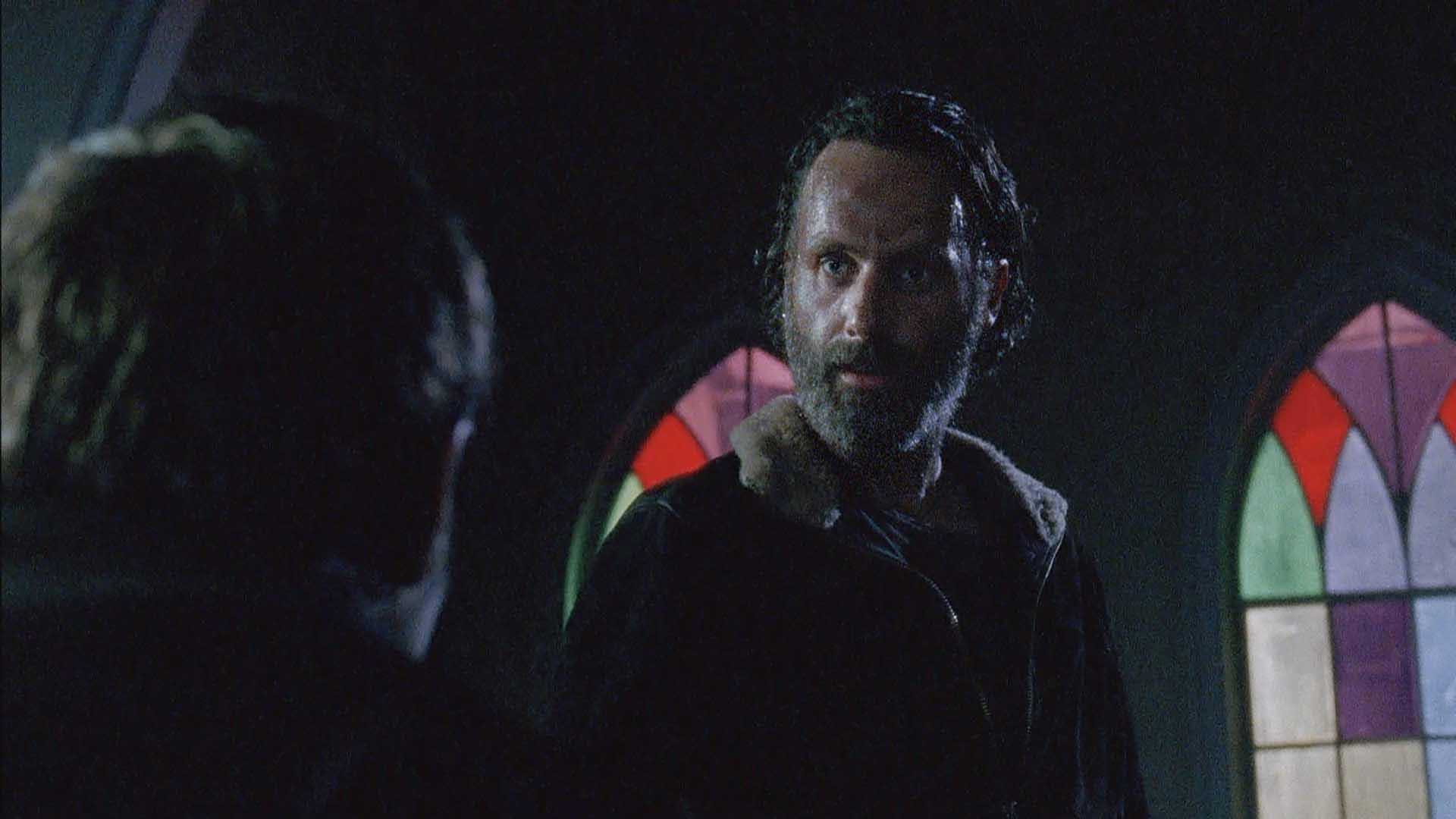

Yes, that location where we built the church has been used for a few different things over the years, but it went up and lasted a season and a half before they took it down. This scene was shot in the daytime, so everything was blacked out. Then I had to add the window light and the source light for it. But this scene plays into what I was talking about before in regard to video assist and making things dark: that moment when Rick comes through those deep shadows and the producer was watching the video assist just didn't believe it was gonna be as dark as I said it would be. Well, it’s pretty dark!

This clip demonstrates those — as you described — “hero-'em-up” shots on Rick.

Exactly. Last year, I was asked to write a little piece about lighting for ICG magazine about my work on the show and the title of the article was “How Low Can You Go?" They had talked to a few cinematographers who shot different formats, specifically about trying to get dark in a scene. [For this scene] I just figured we'd go for it and see how dark we could make it. You know, the 16mm does show some grain, as you could see. That’s just the nature of it. And when you get it this big on a [theatrical] screen like this, you can really see it swimming. But, again, the grain adds to the effect of it being what it's supposed to be. And, this scene in particular, I think came out the way that they wanted it. So, in the eyes of our director, producers and writers, it was a success. That's all I can ask for, right?

Audience Member: What lenses do you use?

Zeiss Ultra Primes. That scene was all shot with primes. The day when we shot that, we had three cameras working. Interestingly, in the primary shot of Rick in front of the stained glass windows, it looks like he's got angel wings. That's what I noticed when I saw the dailies. If you look at some of those frames, he’s got these two little wings behind him, as if he’s coming to save the day. But I don’t think there are any angels who would act quite like that!

American Cinematographer: Well, he's definitely an avenging angel in this case.

Oh, man, Rick’s been through a few things.

Audience Member: Moonlight is a primary source whenever you're shooting nighttime scenes. Is there's a formula that you go by in terms of it’s color or intensity?

I inherited that moon, because it has been with the show for a few seasons. To me, personally, I think it's too blue. Because the moon, when you go out at night, doesn't look like that. I chalk it up to this being a comic book moon. But what I've discovered is, when you mix that color moon with firelight or candlelight, it's a hard thing to work with when you go into color correction. Because you're on opposite ends of the color spectrum — very cool and very warm. Then when you're dealing with skin tones, you have to decide which way to go with it.

So, this year [while shooting season seven], I've been bringing the moon down by taking some of the blue out of it. That extreme color difference just became too difficult to deal with. When you go to color correction, you're always trying to make it look presentable, even for the actors. So, for example, if you have firelight and moonlight in a scene, and you decide, "Well, the firelight's a little too warm" and you bring it down, the moon just turns a completely different color and skin tones are affected as well. So you're totally isolating things.

But this show has always had a blue moon. Because if you look at different shows and different features, the moon's always a different color. And if you go outside on a full moon, what color is it really? I mean, I've done moons that have green in them. You get a green moon. Or you'll have a moon that's white. It just depends on the creative choice for that particular story.

American Cinematographer: I’ve heard other cinematographers talking about sort of the creative tyranny of the blue moonlight.

It's a whole conversation you can have. Because if we all sat outside on a full moon and we asked, "What color is that?" We’d get many answers. It's so subjective.

Well, it all depends on where you are geographically as well.

Right. I mean, I once saw a moon that had magenta in it. And I'm asking myself, "Boy, what is that?" So it's definitely a creative choice. But I found that now, since we mixed a lot of firelight and candlelight with moonlight, that the blue became difficult on that spectrum. So I brought the moon back down. The moon right now is pure blue, which would be what we call our HMI lighting, which is our daylight lighting. So they use the HMIs as a moon source, try to warm that up a bit. So I bring that back with a little bit of color. I put warmth in front of it so it's not quite as blue.

Audience Member: So you’re using gels instead of doing it in post?

Yes. For those here who don’t know, there are two basic kinds of color-correction gels that you use for lighting. You have CTO [color turns orange] and CTB [color turns blue] — the blues and the oranges, each of which some in a variety of intensities — eighth, quarter, half, full — so you can tune the color exactly the way you want. If you're using a tungsten source and you want to make more blue, or cooler, you use CTB gels. I use a color temperature meter and know that that color of the moon is, say, 5500°K, but I want it to be warmer, like 4300°K. So I would put maybe half CTO in front of it and know that color is going to be in line with the direction I want to go. On one particular episode we [wanted a distinct look] so we added a little bit of eighth or quarter green. Because sometimes the moon feels green, you know?

American Cinematographer: And, of course, every time you put some of these color-correcting gels on your lights, you're also reducing their output, so you have to have a careful balance between what kind of output do you need and your creative need for those color differences.

True. And then, for example, when we've had to light Alexandria with full moonlight, sometimes we have to do the large outdoor space. So I’ll often have three lights up in the air creating moonlight. Just because the long throw of the lens is seeing way into the background.

Would you use Condors or balloon lights?

We use balloon lights and we also use Condors, 80-foot and 100-foot Condors with what we call “cube lights.” They're basically boxes made of 12 by 12 diffusion frames. Each has has four light sources inside, and you can combine HMI with tungsten sources so you can bring your color temperature where you want. Since it's a cube, you've got all those areas that the light can come out of. So you say, "Well, I don't want it coming here or here." So you make a choice before it goes up, and you say, "Block that side out and block the back out, 'cause we don't want to light the trees," or whatever.

A balloon light, for people who don't know, is literally a giant balloon that has lights internally mounted so that the entire giant balloon becomes a huge soft source.

And the helium you use is often more expensive than the lights themselves — it has skyrocketed in cost. So they're now going in different directions with the advent of LED lighting, as the manufacturers move away from the old hot lights — which would be HMIs or tungstens. LEDs much more efficient and now have almost as much output, but they're not so hot. But, then, personally, I don’t think they don't have the color value that I’m used to in a tungsten source. It's like going from a tungsten bulb in your house to an LED bulb. And, to me, the tungsten bulbs still have a better feel to them. They're an organic source, while LEDs are electronic. And you can control the color temperature, the dim-ability of them, just by a panel. So now what the guys do is they have an iPad and they walk around the set, and all the lights are controlled remotely by an app. So they say, “We want that to be a different color.” He just dials it in; it goes from warm to cool. Before, you'd have to have a guy go up in the air, change the gel, maybe bring the lights down. So the industry's advancing as quickly as everything else is, technically, because of the fact that everything’s becoming electronic.

On Halt and Catch Fire, we had LED panels rimming the outside of our sets, just banks of them. They're eight feet long. You can gang ’em together and can have daylight; you can have moonlight; you can have early morning — all controlled with a laptop. You just plug in what you want, the outside of the windows will change color, and you're ready to go. So you don't have to say, “Okay, we're going to nights now. Let's change all the gels.” You just push a button and it’s done. So that’s all coming down the pike.

But this particular scene in the church [from “Four Walls And A Roof”], those actors — like Gareth [played by Andrew J. West] — are really, really good. I mean, we've come across some really good actors that unfortunately don't live very long on our show. [Laughter] You wish you could see him more, because he was so like the unnerving “guy next door” who happens to be a cannibal, you know?

Well, that scene, too — not only is it dark, but very monochromatic. So it plays into that feeling of dread. And there toward the end, as Gareth meets his end, it's pretty gruesome, though certainly not the most gruesome thing that's ever been on The Walking Dead.

No.

But we were talking a little bit earlier about things sometimes becoming too gruesome, and that you have to, maybe later, in post, tone it down a little bit.

Yes. And an example of that is a scene we’ll watch next, with Noah [played by Tyler James Williams] and Glenn [Steven Yeun] trapped in the revolving door. That was an episode I shot with [director] Jennifer Lynch, who's the daughter of David Lynch. She's a real sweetheart. What a character. She had the most jokes I've ever heard from anybody in the industry.

As Noah is pulled in by the dead and torn apart, we see a great combination of camera, performance and prosthetic effects. And then there's a little bit of digital layering there. And can you explain why?

We shot that scene without the blood on the glass, so you saw the whole thing happening right before your eyes. Greg [Nicotero]’s company made a complete prosthetic version of Noah and it was an exact-looking replica — with layers of tissue, bone, teeth and everything — so when [the walkers] pulled it apart, it came apart very realistically, in layers. But when I saw the show air, they’d added that splash of blood on the glass [in post] because they probably wouldn’t have been able to air it, otherwise — it was a little too much.

That location we shot the scene was a glass and steel building that was literally all glass on that south side of the structure. We filmed this in October, which meant the sun was going be in the shot the whole time. There was no control over that space to keep it from being way too bright. So we had to black out the whole side of the building. We dropped these 50-foot blacks down from the roof and covered all the glass except for one section that I put just enough light through to hit the revolving door. Generally, I don't get to choose locations. I just showed up and they said, "This is where we're shooting." And I said, "Well, this is like we're shooting outside. We have no control over this at all."

The revolving door was something the art department brought in and installed in the building’s foyer. They didn't even think about the fact that the windows went straight up above it like three stories. Basically, the day we shot it was cloudy — the sun would come out, a cloud would come over, and we’d lose our sun, all day long. If we didn't have control over that, we couldn't shoot for any length of time, so we just took the sun away.

Was there any opportunity to possibly shoot that location at night — and do night-for-day — instead of fighting the daylight? Or was it a scheduling issue?

It's all scheduling, and they try to stay away from nights when they can. But the scripts obviously dictate where we're gonna go. I mean, they've changed scenes from night to day just because they knew the costs involved with shooting at night.

What I also liked about this scene was the texturing in the windows and the fact that we had all those reflections, all the muck on the glass and all those featured zombies.

When they bring zombies to the set, they categorize ’em and they're layered in how they're gonna be seen by the camera. “Features” are heroes — the most detailed zombies — then we have “mids” and “mid-backs” and then “deep backs.” [That layering of the zombies is an issue] when Greg’s guys are putting together their list of who's gonna be in three hours of prosthetics — ’cause “features” take about three hours each, depending on how intricate they are.

And elaborate makeup effects — like the Noah kill in this scene — take weeks or maybe months to build.

That scene took five hours to shoot just the kill, because it's done in three layers: it's the actor, then it's the prosthetic and then it's putting the blood in. And the prosthetic Noah took five guys to operate. So just to do one shot like that takes a lotta time. But yeah, Noah went down in history. That’s one of the top-10 best kills on the show.

Audience Member: What techniques were you using to avoid camera reflections through all of those revolving doors?

Oh, we just paid particular attention to it. We had three cameras working to cover that scene, because what we wanted to do was capture that moment when they're all freaking out in one take — so the actors can rely on each other — let them react to what's happening. You know, we filmed the very last shot with two cameras because that's the special one. But when [our actors] Tyler, Steven and Michael Traynor were all reacting to each other, we just found angles where we could use the reflections and see what we're seeing but not see each other.

American Cinematographer: So you didn't use polarizers to reduce reflection?

No, we actually wanted to use those kicks. I was hoping we would've gotten more in one of those shots where you could actually see more zombies around the corner, but we couldn’t make it work. That was all the way it was. We didn't have to remove any [reflections] either. In a situation like that, that's what they would call a “CGI cleanup.” Somebody'll go in and say, "Oh, there's a reflection. Let's paint it out." But, of course, how much does that cost? So we always try to avoid those situations.

That goes back to the joke of "fix it in post," which never costs less money.

Never. I was on a feature called The Reaping. We shot in Louisiana with Hilary Swank. It was not supposed to a big CGI show, and started out with only 90 effects shots. But the project went through some serious turmoil because it just wasn't a good show, and after they tested it, they said, "Oh, this isn't working." By the time the show was finished, it had 450 CGI shots. And all I heard when we were shooting was, "Oh, don't worry; we'll paint it out." And I kept hearing that, because they were rushing. "Hurry, hurry, don't worry. We'll paint it out." And then the producer walked on the set one day and said, "I don't wanna hear that anymore."

He started getting the bills.

Yeah. It costs money to paint things out. That was 10 years ago, and so the advances and what they can do is just phenomenal — even just in the last three years. So after last 10 years, the way they work in post today… I mean, what they used to do in a big suite they're doing on a laptop now.

We have about 15 minutes or so left. Why don't we watch the last clip, and then we'll open it up to additional questions?

Great.

Poor Denise [laughs].

Yeah. So that was [actress] Merritt Wever, who I thought was, again, a great actor who didn't have a long life on the show. But she really brought it. In that episode, when she was on the railroad tracks and she had to tell off Daryl and Rosita, I thought she really brought some acting to that moment, just before she got taken out.

But this scene [in the shop] — I don't know if you could notice it projected on this screen — but this was one of the places where I added a little green to the lights just to give it more of a moldy or septic tank kind of vibe. The floor was all green and moldy and had water on it, and the store was supposed to have a hole in the ceiling. So, again, I was trying to keep it dark, using the prop flashlights as a motivation. We shot that in a practical location in a strip mall in Georgia and [the art department] just took the place over and re-dressed it completely. They brought all that stuff in. Then, Denise finding the [zombie] mom in the back was kind of a moment for her. But that was a fun one to shoot. And it's always fun to shoot with Norman [Reedus]. He's a character and a half.

We talked a little bit about the way the camera always sees Rick in the hero position. Are there varying degrees of that low-angle shot for each of our heroes? Do you shoot Daryl differently than you do Rick?

Yeah. We shoot them all differently. And it depends on the plotline and the story of the show. Because there are moments when Daryl isn't in the hero position, where he's maybe looking very potentially in trouble. So you change the angle based on that particular story. It's part of using the camera to tell the story. And then the girls also — if one of them is taking a hero's position, then you would. But, generally, you don't want to shoot women from underneath, looking up their noses. We try not to do that. But there are certainly moments when hero-up Maggie or Carol or, in the case of this scene, Rosita. But, generally, I'll shoot them so they look good.

One of the ways we also do it is that we always tend to shoot those shots wider and closer. You'll see a lot of shows that just shoot coverage, and they'll just start with a wide shot and then zoom in and get tighter and get tighter all from the same place. So if we were to shoot a scene in here and I was to shoot you and you were here, I would just shoot you here and go tighter and tighter and tighter from here. But what we do on our show is we'll master wide from a distance, see a big space, and then when we do the coverage, we move in closer. And then even closer for close-ups — of, let's say Rick and Daryl — where we might be shooting them within just three feet of their face.

On some other shows, they'll shoot close-ups with a longer lens and compress the image while shooting the same size. Instead of using a 24mm lens, you'd be shooting it with an 85mm. So the image changes, and that changes the whole feel of the frame, because you're no longer in what you would call a “cinematic mode,” because now you're not looking at the whole space. Instead, you're just looking at a section of it by compressing the image.

Well, and the use of the different lenses not only changes the sense of compression of space; it will literally change their bone structure, the shape of their head.

Totally, and that makes a big difference. It has an effect on the emotional sense in the way you're shooting too. Because you could just put the camera in a different place and it changes the whole frame. You could be higher or lower or just move it over. And, again, going back to what I said earlier, as a camera operator, actually looking through the lens, and looking through a film camera, you see the shutter moving, and you're in the moment of someone acting. I've had the opportunity to shoot many of Rick's big speeches in the last few years, and to see it through the lens is just a much more magical thing than watching it on a screen. You know that in that moment, when you get off the camera, that Andrew Lincoln just had an amazing performance.

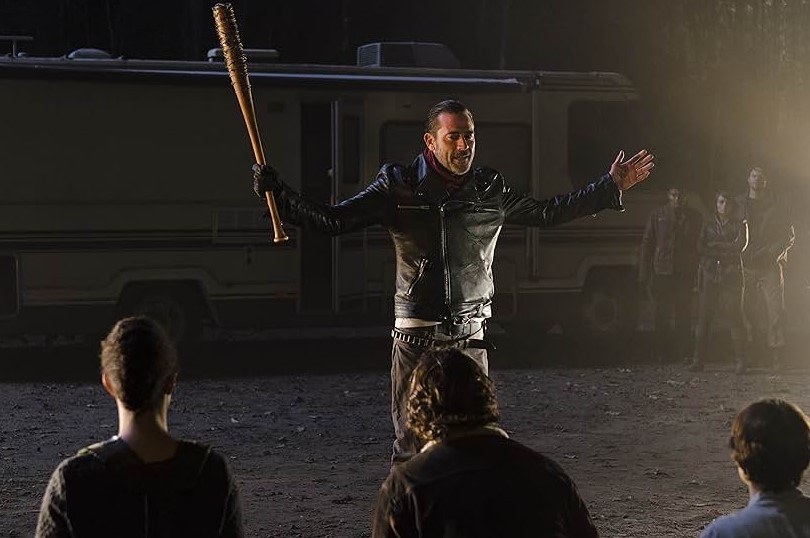

Without spoilers, have you shot a scene yet with Jeffrey Dean Morgan — who plays the villain Negan — and do you have a different way of approaching him?

Well, he's also now in a position of power. He's in control. So he's even more so. He's more “comic book” than anybody. His close-ups are from way down low. We shoot way underneath him, because he's such a dominant character. And Jeffrey [Dean Morgan]'s gonna bring a lot to the story. He's a really good actor. And he's taken the Negan character and gave it a whole new life. It's kinda fun to see.

Audience Member: I was glad that you showed the clip in the church, because that’s my favorite scene of the entire show. I know you can't always control your circumstances, but how much would you say your favorite shots in the show are luck and how many of them are planned?

Well, there were some in there that were planned, but most of the ones that you feel are amazing are luck. Happenstance. They just happen to all come together. One of my favorite shots is in the one clip we saw as Rick's standing over Gareth in front of the stained glass windows. At some point I noticed that the stained glass, to me, looked like the wings of an archangel. But things like that are really about how things come together. And it's just having the preparation in line so that you can handle anything that comes down the pike.

We did some stuff this past week that I thought was just amazing. We just happened to be shooting on a rooftop at sunrise after it rained. And the characters are walking across the roof and there was this big puddle of water. So we had this mirror effect. And we're shooting into the sunrise. In that moment, everything came together for a moment that you could say made some nice pictures, you know? That same day, we ended looking the other way, into the sun. The characters are walking and we got this amazing flare as they come into the shot. We can't plan on those kinds of things.

American Cinematographer: What you're describing, of course, reminds me of the great quote from cinematographer Conrad Hall [ASC], who credited those kinds of happenstance artistry as his “happy accidents.”

Those are happy accidents. Yeah. There's a film called Days of Heaven that was shot almost entirely in existing light by Nestor Almendros [ASC]. But he shot the whole show based on where the sun was. The luxury of that doesn't exist anywhere. It doesn't even exist on features unless you have as much control as a Roger Deakins or as a Conrad Hall used to have. Nowadays, it's often all about schedule, schedule and schedule. And even on big features, I see non-matching shots all the time. It's unbelievable. You'll see a shot where you're having a dialogue scene and someone's talking over there and they're brighter than the guy that they're talking to and they're standing right next to each other. And this is a $100 million feature. This is because you don't have the control you used to have back 20 or 30 years ago.

Cinematographers used to have so much more control. They used to run the set. They would say, "No. I can't shoot today. It's too cloudy. Let's all go home." They actually used to do that. Now, again, it's all about schedule and budget and making your days. And, in my position, if you don't make the days, then your careers are short. Because it's all about being able to say, "I can do this much work in this much time." And if they're constantly not getting their shots, then it becomes, "Why didn't you?"

I mean, for example, we did a scene this past week and shot five masters in the morning — five of the same shots with three cameras. So, think about the volume of film that we’d shot. And all of a sudden, on the fifth one, Andy Lincoln looks at his hand and says, "I'm supposed to have something on my hand." A bandage. And we just shot five takes with three cameras. So those things happen. But they don't happen very often. And if they continue to happen, in our industry, that becomes: "Well, why did it happen?" And then it becomes, "Who's responsible?"

And then, who's not welcome back on set tomorrow?

Exactly. So it's a kind of a brutal industry in that respect. It can be fun. It can be exciting. It's not glamorous at all. And we sweat a lot. We breathe all kinds of weird stuff. And there are very long days. You're really tired on the weekends. But there's some reason why we keep doing it. And, for me, it’s because I've always wanted to do it, right from the beginning. I guess you could say you must be lucky if you can do what you love to do.

Well, we're going have to leave it at that. So, love what you do, and make your days [laughs].

That's it. It's very important to make your days.

So thanks a lot everybody for being here.

Yes. Thank you. Appreciate it. It was good fun.

(Click here for Part I of this interview.)

For access to 100 years of American Cinematographer reporting, subscribers can visit the AC Archive. Not a subscriber? Do it today.