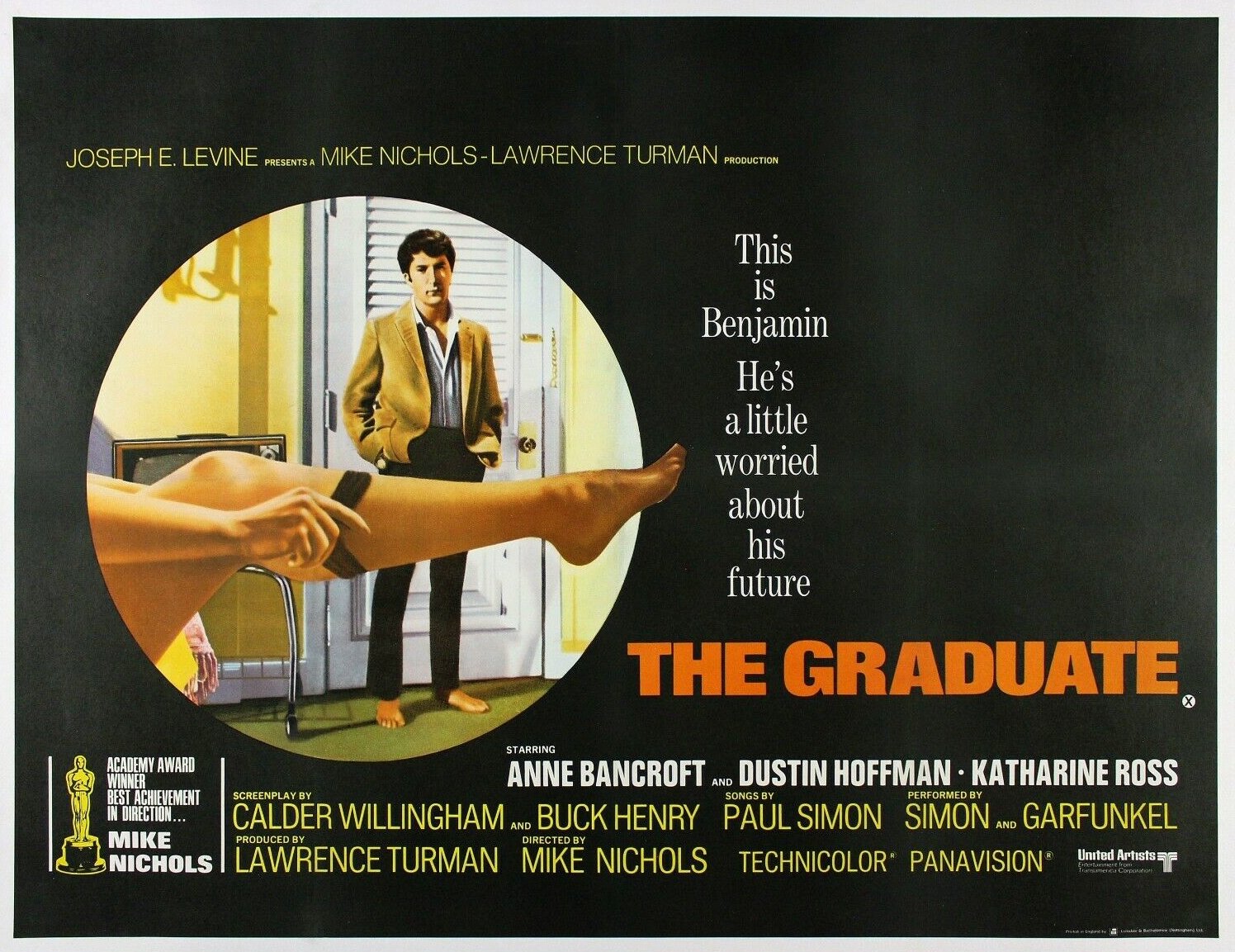

Wrap Shot: The Graduate

Robert Surtees, ASC delivered “rule-breaking mad, Mod visual acrobatics” to this relentlessly unconventional romance.

Veteran cinematographer Robert Surtees, ASC’s camerawork in The Graduate was described by AC editor-in-chief Herb A. Lightman as “rule-breaking mad, Mod visual acrobatics” in his Feb. 1968 article “Cinematographer with a Split Personality.” He went on, describing that the 1967 feature has “been realized on film with a photographic style that defies conventional semantics. Surtees calls it ‘ultra-modern’ but it is something more than that. It has touches of ‘Mod’ and a faint aura of avant-garde, overtones of the ‘underground’ and flashes of cinéma vérité. It even includes one or two sequences of slick ‘glamor’ photography, where the script calls for a sophisticated patina. It breaks almost every rule in the cinematographic textbook to create visual excitement on the screen.”

It would take an experienced cinematographer who actually knew exactly what rules to break in order create something so unusual for The Graduate.

Born in Covington, Kentucky, on September 8, 1906, Surtees became an amateur photographer while in high school and later found work as a photographer and re-toucher at a portrait studio in Cincinnati, Ohio. After studying photography in New York City, he moved to California in the early 1920s, where he shot a number of scenic pictures that were published in Towing Topics, the magazine of the Southern California AAA. The head of the camera department at Universal Pictures, C. Roy Hunter, was so impressed with the photos that he offered Surtees a job.

By the age of 20, Surtees had served as a camera assistant on minor projects for ASC members including Harry Neumann, Jerry Ash and Jackson Rose. His first big-budget picture as an assistant was the Victor Hugo adaptation The Man Who Laughs (1927), photographed by Gil Warrenton, ASC.

As assistant to Charles Stumar, ASC, Surtees then spent 1928-’29 in France, Germany, Switzerland and Italy — working for for Universal and UFA.

Returning to Los Angeles in 1930, Surtees assisted and then operated for Hal Mohr, ASC on numerous pictures at various studios. He also seconded for ASC members Stanley Cortez, Joseph Valentine and George Robinson at Universal.

His first assignment as director of photography was This Precious Freedom (1942), a propaganda film made for the U.S. Army that was only seen by military audiences. After shooting adventurer Frank Buck’s South American expedition picture Jacaré (1942), the cinematographer launched a 20-year tenure at MGM, followed by many more years working as a freelancer.

In that time, Surtees won many awards, including three Oscars — for King Solomon’s Mines (1950; filmed largely in Africa), The Bad and the Beautiful (1952), and Ben-Hur (1959, shot in 65mm Panavision anamorphic 2.76:1 widescreen). He also received Academy nominations for Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo (1944; with Harold Rosson, ASC), Quo Vadis (1951), Oklahoma! (1955; the first film photographed in Todd-AO) and Mutiny on the Bounty (1962).

In short, Surtees was just the seasoned pro Mike Nichols needed for The Graduate.

“What made it such a challenge was that, first of all, [Mike] Nichols regarded the vehicle as an almost surrealistic blend of extremely funny satire and tender pathos.”

— Robert Surtees, ASC

As Lightman described, after his camera duties were complete on his other feature to be released in 1967, the big-budget fantasy project Doctor Dolittle, “Surtees checked onto the Paramount lot to take up his chores as director of photography on The Graduate, which had been adapted from a rather dull and strangely humorless novel dealing with a confused young man's introduction to sex (through the medium of an older woman) and ultimately love (as personified by her daughter). On the surface it seemed like the kind of film that any skilled cameraman could photograph with one eye shut and it might not have interested Surtees except for the fact that it was to be directed by Mike Nichols, whose work in Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? had greatly impressed him.

“Preliminary discussions with Nichols soon dispelled any fears Surtees might have harbored that The Graduate might turn out to be an ‘ordinary’ picture. Quite the contrary. He was later to say: ‘It took everything I've learned in 30 years behind the camera to be able to do the job.’

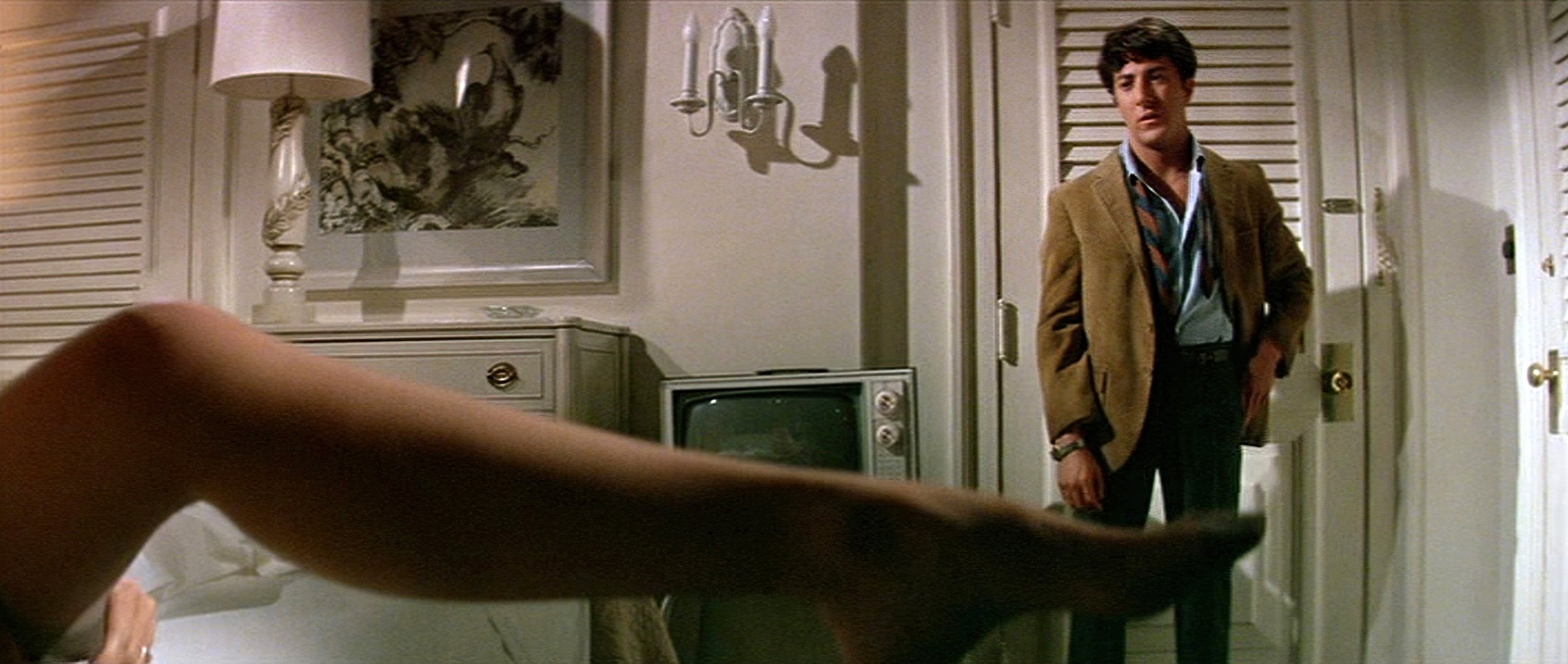

“What made it such a challenge was that, first of all, Nichols regarded the vehicle as an almost surrealistic blend of extremely funny satire and tender pathos. It was to be subjective in the sense that the way things looked should reflect the attitudes of the bewildered non-hero alienated from an affluently hostile world. Such attitudes are not necessarily ‘realistic’ (in the conventional sense) and the photography had to convey this unreality at times — without going all-out psychedelic.

“Big Bob is the most adventurous man I’ve ever worked with. He was absolutely game to try anything. The joy of working with him is that along with his zest, he has so much experience he invariably knows how something is going to look on screen.”

— Mike Nichols

“‘It wasn't long before I realized that to put Mike's concept of the story onto film visually, many of the things that had seemed like good technique over the years would have to be cast aside in favor of a new and different approach,’ Surtees explains. ‘For example, ever since the late Gregg Toland, ASC made us all sit up and take notice with his wonderful photography of Citizen Kane, the standard of excellence in cinematography had come to mean the sharpest possible image and the greatest depth of field. But I had been talking with Nichols about how wonderful it would be to obtain, in certain sequences of this picture, a sense of semi-reality with dramatic overtones in the photography. This meant, of course, that we'd have to sacrifice some of the sharpness and emphasize selective focusing, where we kept the subject we wanted to be sharp in focus and let the foregrounds and backgrounds go out-of-focus. It occurred to me, also, that weird camera angles used for no logical reason would not give the film a new look, but could be a disaster. One can overact with a camera more easily than with an actor.’

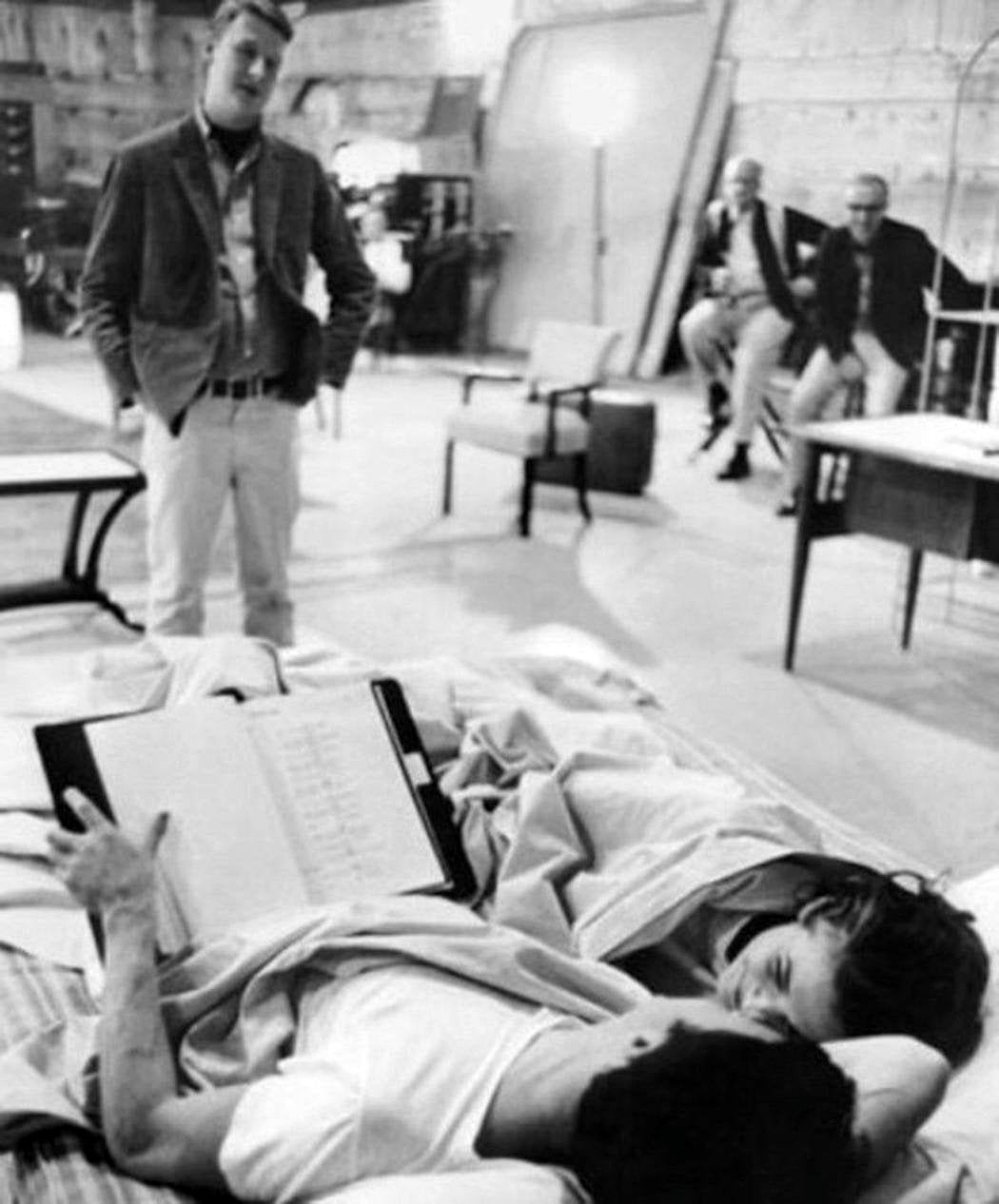

“Having thus established nebulous guidelines for his approach to photographing The Graduate, Surtees sat in on the three weeks of pre-rehearsal which Nichols conducted on an empty sound stage. Art director Richard Sylbert had marked out on the floor the exact configurations of the various sets, using masking tape.

“The actors had memorized the entire script in advance, and now each scene was discussed and thoroughly blocked. During the final week of rehearsal, after movement and inter pretation had been definitely set, the entire picture was pre-planned, cut by cut, and camera angles were selected for each scene.

“Of this unorthodox practice, Surtees observes: ‘Major studios frown on pre-rehearsal because of having to put actors on salary so far ahead of shooting, but, on this picture, it really paid off. All of us, cast and staff alike, had a complete grasp of the picture before we even shot the first scene. We had something to think about and to be prepared for. During the shooting phase that followed I found myself constantly searching for different ways to shoot scenes in order to give them more emotional meaning. I don't claim that what was done photographically was always original, but some of it I had never seen done before during all my years in the business. To get these results, we used hidden cameras, photographed night exteriors using only 'available' light, pre-fogged the negative, pushed development and did just about everything else that's possible in cinematography. It wasn't done because we wanted to be members of a 'new wave,' but because it was the only way that, technically, we could get what we wanted onto film.’

“To achieve the effect of unreality and selective focus in certain sequences, Surtees found himself using lenses of much longer focal lengths than usual. The Big Daddy of them all was a 500mm giant that looked like a telescope. The only drawback was that the depth of field was so shallow that it would have been almost impossible to obtain critical focus unless it were mounted on a reflex camera. Just at that time, Panavision had completed a single working model of its new reflex camera, and Panavision president Robert Gottschalk was prevailed upon to loan it to the company.

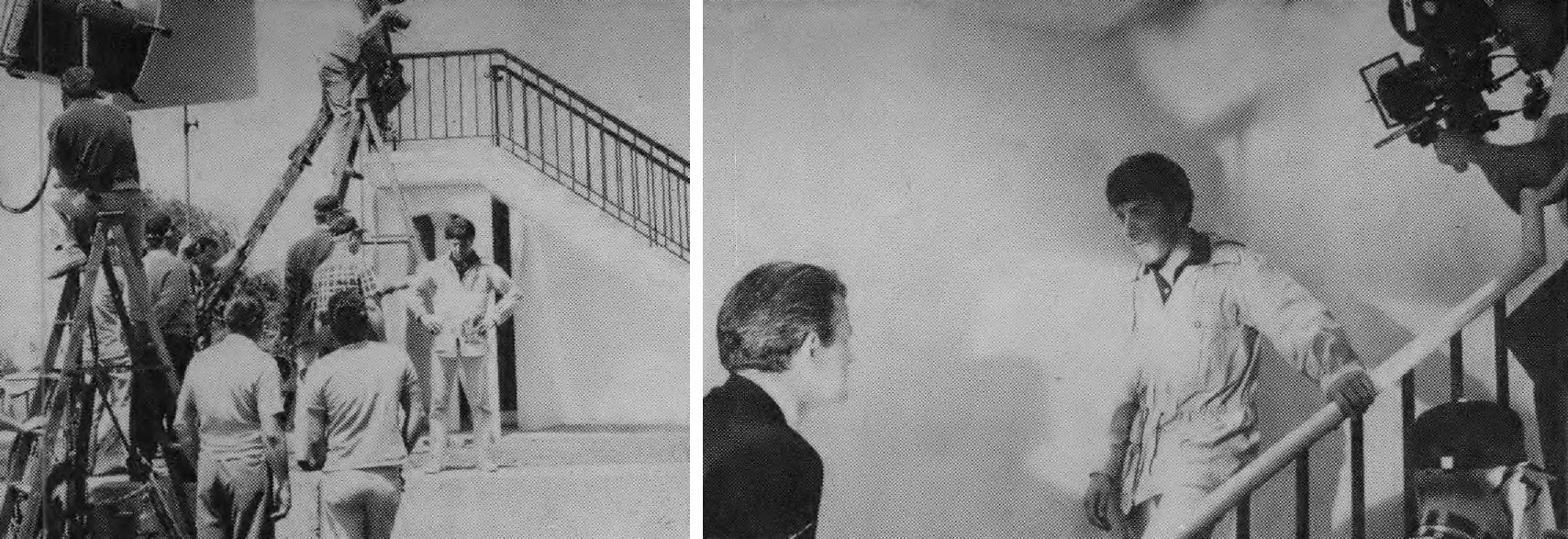

“One of the most spectacular uses of this giant lens was in a dramatic sequence which takes place outside the Whisky-A-Go-Go discotheque on Hollywood’s Sunset Strip. On the Friday night designated for shooting, the Strip teemed with hundreds of hippies and it would have been almost impossible to film a sequence in their midst without unspeakable confusion.

“However, a hidden camera with the 500mm lens mounted on it was set up peering through the window of a gas station on the opposite side of Sunset Boulevard. The lights on the marquee outside the discotheque had been replaced with more powerful lamps so that the Eastman color negative could be exposed, but even at that the negative had to be pushed as far as possible in development. The dialogue of the actors was picked up by wireless lavalier microphones concealed in their clothes. The hippies thronging the Strip were totally unaware that they were part of the action, and the scene has a realistic mood that could never have been achieved on the backlot of a studio.

“Another interesting use of this lens was made in the sequence where the out-of-gas hero is running toward a church to try and prevent the wedding of his True Love to another man. The 500mm lens was used to photograph the boy running straight toward the camera. Because such a long focal length lens condenses compositional planes to an extreme degree, he seemed to be running and running and running without getting any closer surely an accurate representation of his state-of-mind at that particular moment.

“Surtees' decision to pre-fog the color negative for selected sequences and individual scenes stemmed from his efforts to give visual dimension to the half-dream world of the protagonist. The technique has, of course, been used before-most notably by Freddie Young, BSC in his moody photography of The Deadly Affair, but it was felt that it would add a special aura to certain moments of The Graduate.

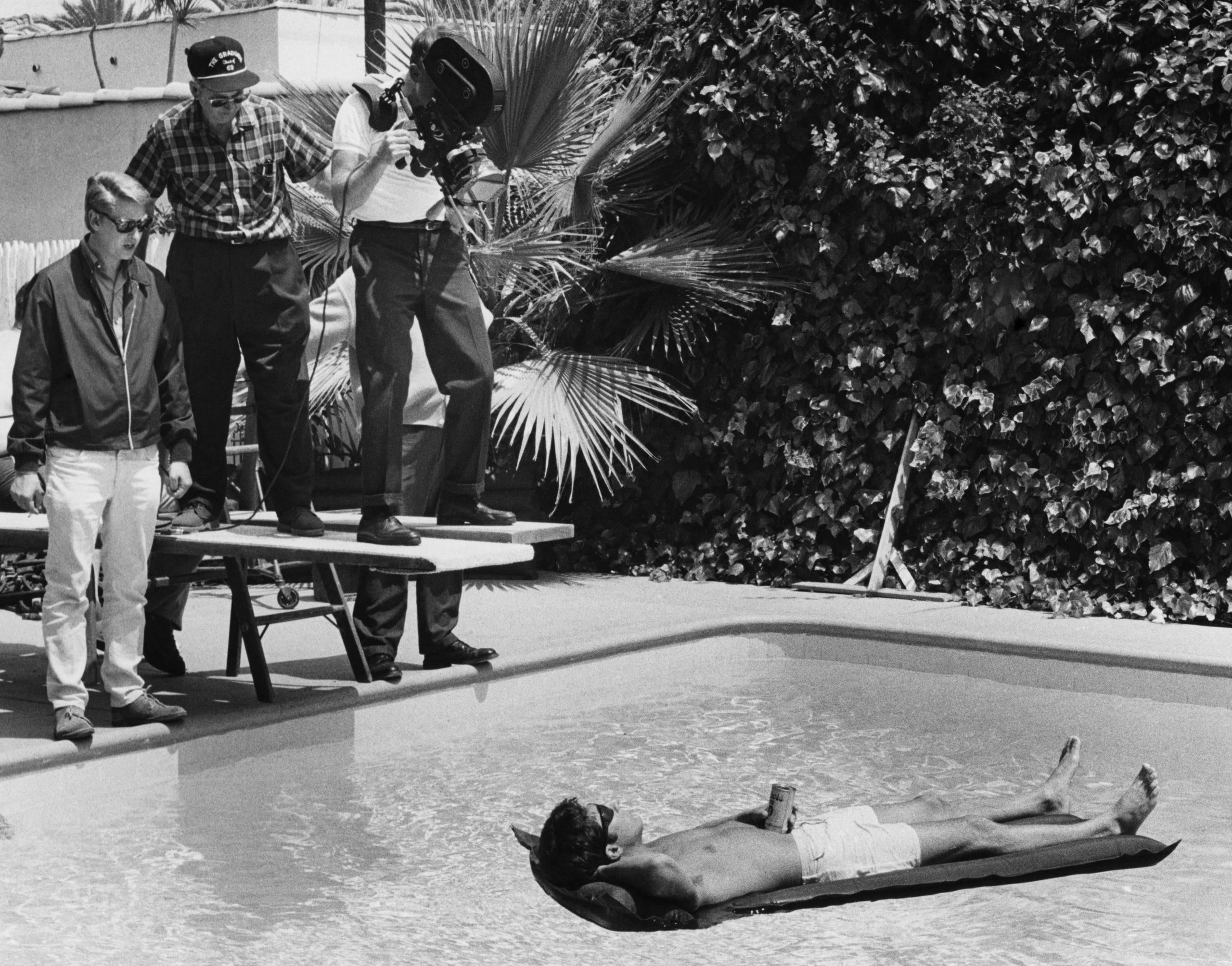

“Tests were made ranging from 10% to 25 % and it was decided that a 17% pre-fog would produce the best effect. Describing that effect is somewhat difficult because it is so subtle, but it is unlike that of the slight graininess achieved through the use of fog filters. The shadows go slightly milky and the highlights shimmer. An especially striking example is a scene at the pool where the boy is lying on his rubber raft and daydreaming.

“There seems to be a slight haze over the scene, stabbed by shards of light reflected from the water. The effect was enhanced through the use of a ‘criss-cross’ diffusion filter over the lens, used in conjunction with the prefogged film.

“To capture the peculiar never-never ambiance of the Sunset Strip discotheque scene, Surtees pre-fogged the film with amber instead of white light. At first, he did his own pre fogging, but when time ran short he turned the project over to the Technicolor laboratory.

“There is a deliberate inconsistency in the various lighting styles employed throughout The Graduate and it is calculated to express visually the confusion in the mind of the protagonist. One of the extremes is manifested in the scenes taking place in the boy's bedroom in Berkeley. It is a small room in a cheap tenement — the kind of room that seems perpetually gloomy, even when the sun is shining brightly outside. To accentuate this effect and create the ‘feel’ of the hot California sun blazing beyond the curtained windows, Surtees poured a tremendous volume of arc light onto the painted backdrops, literally overpowering them with light. Then, disregarding the fact that the script called for daytime, he lighted the interior of the room ‘as if it were the darkest night effect ever photographed.’

“By using the 500mm lens at its widest aperture (F/ 4.5) to expose for the dark interior, the outside view through the windows became a blazing hot, overexposed blur — and it does, indeed, add a special quality to the sequence.

“In shooting on location in the lobby and bar of the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles it became impractical to move in arcs and large incandescent units for lighting the large areas to be photographed. Also, the management would not allow the use of generators because the noise would disturb the guests. Surtees solved the first problem by employing more than 100 quartz-iodine lamps skillfully concealed about the lobby. The current demand was satisfied by tying directly into the main line.

“When shooting on the streets of Beverly Hills the no-generator rule also was enforced. This time sufficient current was provided by installing a pole transformer that could provide almost 500 amps. When even that much proved to be not quite enough, it resolved down to running cables into private homes to draw from the line current.

“Perhaps the greatest lighting challenge came when Nichols decided to include a wild night ride on the freeway, with the hero zig-zagging in and out of traffic. The obvious solution would have been a process screen or a blue-backing matte shot, but the director would have none of these artificialities. It had to be real. Surtees knew that it would take hundreds of arc lights and generators to light several miles of freeway for color photography — even if the police would permit him to blind the motorists with such powerful lights.

“Clearly, an alternative had to be found. Permission was secured to use a completed, but unopened, strip of freeway about a mile in length. The trunk cover was removed from the hero's tiny sports car and an Arriflex was tied down in the trunk space. Four airport landing-strip lights were acquired and two of these were fitted into the headlight wells of the sports car. The remaining bulbs were mounted as headlights on two other cars driving behind the sports car to illuminate the actors. In addition, small lights were mounted on the dashboard to reflect into their faces. All of these lights were powered by extra-strength batteries mounted in the car. Since there was no room for either the director or a camera operator in the car, a switch was rigged so that the actor could turn the camera on himself.

“During an idle philosophical moment, Bob Surtees had said to Nichols: ‘You can add a wonderful feeling of reality to a scene by introducing an element of nature — such as rain or fog or flowers.’

“His words came back to haunt him when, prior to shooting a sequence that called for the hero to drive three blocks through the residential streets of Beverly Hills, Nichols said: ‘We're going to play that sequence in the rain.’

“But how?

“Rigging three blocks of Beverly Hills real estate for manufactured rain was obviously out of the question. ‘The people who live there don't even allow it to really rain,’ comments Surtees. He racked his brain for a way to do it simply and came up with a ‘Mickey Mouse rig’ that, nevertheless, produced a most realistic effect on screen. A water pipe fitted with a special nozzle was mounted over the car in which the actors were to ride, and Special Effects men poured water down on them from a tank carried on the camera insert car. Mounted on the camera for a close two-shot of the actors was a long telephoto lens that threw the background so far out of focus that the lack of real rain was not apparent. There was, however, what appeared to be pouring rain on the windshield and the top of the car — and that made it believable.

“‘Driving down Palm Drive with this jerry-built rig, we must have looked like the Hollywood 8mm Movie Club shooting its Sunday epic," muses Surtees, ‘but it worked!’

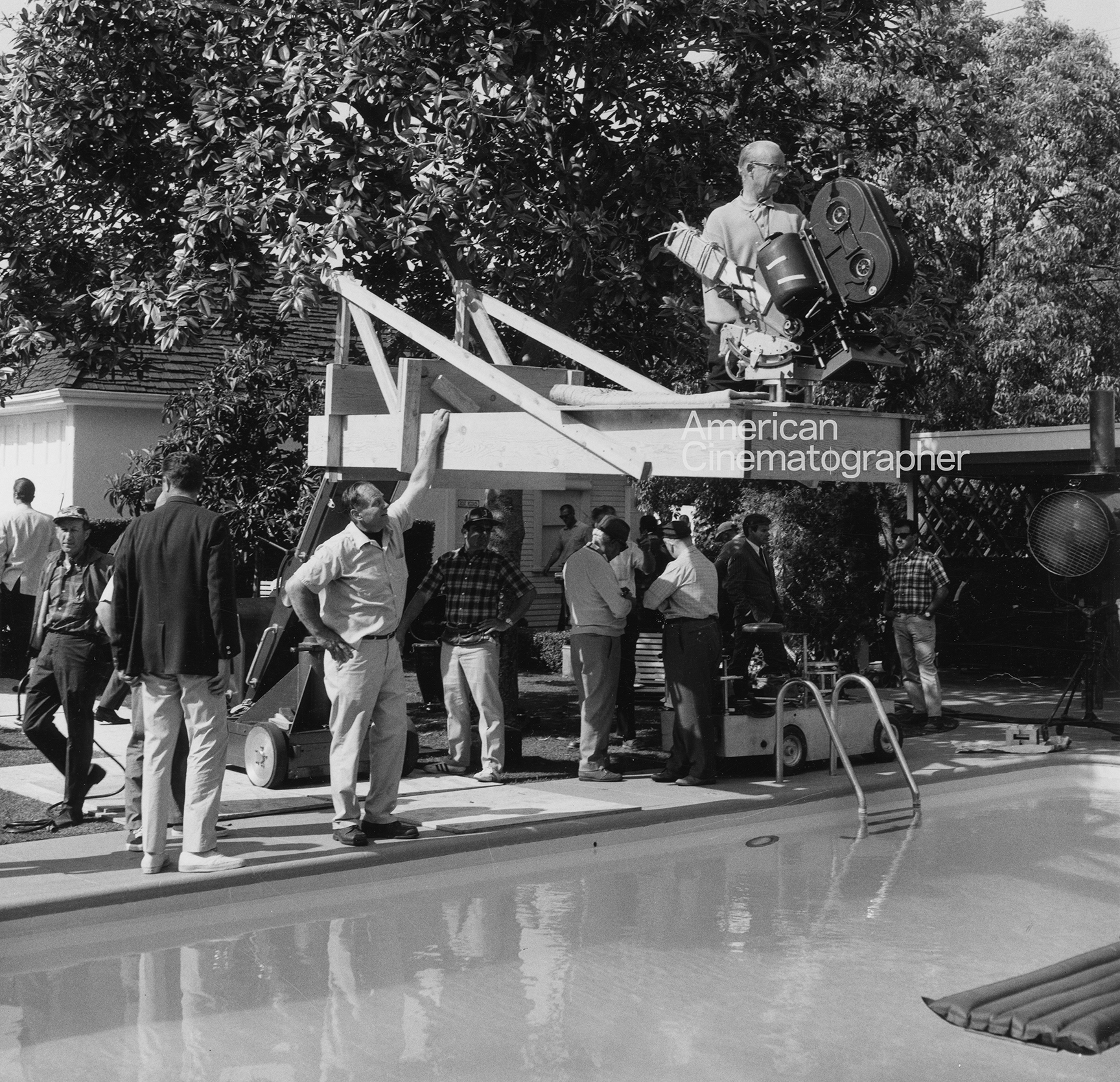

“A sequence notable for its originality and sheer virtuosity of technique is that in which the reluctant hero, having been given a complete scuba diving outfit by his father, is goaded into demonstrating same in the family pool. He is first shown complete with wet suit, air tanks, face mask, fins and spear gun-after which the camera goes completely subjective, assuming his point-of-view as he flaps out of the house and dives into the pool.

“To create the effect, an Arriflex was fitted with rods under the lens to support a face mask of the right size to simulate realistic framing. The camera operator wore fins and several times, as he stomped toward the pool, these huge flippers would come up into the shot. Since the Arriflex was not in an underwater housing, the operator could not actually dive into the water with it, as the script demanded. Instead he walked right up to the edge of the pool, lowered the camera to about six inches from the water, and did a quick swish pan across the surface.

“At this point a quick cut was made to a shot in which the operator, using the Panavision Underwater Camera, repeated the swish pan across the surface and then dived directly into the water. The subjective viewpoint continued as he swam about the pool and then tried to surface, only to be pushed back into the water by the father's hand on the face mask. (Surely some Oedipus symbolism there!)

“By skillfully cutting the two scenes together in the middle of the swish a continuous scene was achieved.

“Surtees comments: ‘On The Graduate, I had to forget all the years of trying for perfect photography. On that film, it was not how beautiful the photography was that counted, but how emotional and exciting it was. For me, this challenge was very stimulating. The days flew by all too fast, and each one seemed like a separate creative life. I was impatient to get to the studio each morning and waited with anticipation to view the dailies each evening. Such enthusiasm can only be inspired by a director like Mike Nichols. I have never seen such a drive for perfection. He has impeccable taste and his knowledge of cinematic technique is amazing, especially since this was only his second motion picture assignment. He has already earned his place as one of our truly great directors.’

“The admiration is not all one-sided. Of Surtees, Nichols says: ‘Big Bob is the most adventurous man I’ve ever worked with. He was absolutely game to try anything. The joy of working with him is that along with his zest, he has so much experience he invariably knows how something is going to look on screen. I had a very complicated visual image which he dug immediately and augmented constantly. He was a revelation. And he has something I had never seen before — a deep unspoken knowledge of what each scene is about. He could always find a visual equivalent for the mood of each scene.’”

The Graduate became a massive hit, capturing the imagination of a new generation of filmgoers while perhaps scandalizing the previous one. Surtees earned an Academy Award nomination for his expressive work in the picture while earning a second nod for his more conventional approach to Dr. Dolittle, directed by the very capable Richard Fleischer. He lost to Burnett Guffey, ASC, whose camerawork in the crime drama Bonnie and Clyde was equally ambitious.

Surtees’ later career included major studio pictures intermixed with smaller pictures that became “New Hollywood” classics, earning additional Oscar nominations for Summer of ’42 (1971), The Last Picture Show (1971), The Sting (1973), The Hindenburg (1975), A Star Is Born (1976), The Turning Point (1977) and Same Time Next Year (1978).

His son Bruce also became an exceptional cinematographer, working for many years with Clint Eastwood on films including The Beguiled, High Plains Drifter, Firefox, Honkytonk Man and Pale Rider.