A Century of Inspiration

ASC members discuss the Society’s list of 100 milestone films from the 20th century.

ASC members discuss the Society’s list of 100 milestone films from the 20th century.

By Jon D. Witmer and Andrew Fish

All images courtesy of the AC Archives

As the American Society of Cinematographers embarks on its second century, an important part of its mission remains the preservation of cinematography’s history. Toward that end, the Society earlier this year released its list of 100 milestone films of the 20th century. Organized by Steven Fierberg, ASC, and voted on by the Society’s active members, the list honors the significant achievements of cinematographers whose artistry changed or furthered the art and craft of the profession, and whose impact continues to be felt in the cinema of the 21st century.

“I believe that as individuals and also members of the ASC, we need to share with the public what influenced and inspired us in our work and our artistry — films we all consider landmarks in our profession,” Fierberg says. “It is our hope that the list will help cinematography to be better understood by the public — the audience — [and to showcase] each of us as an artist who is an essential contributor to the magic of cinema.”

The process of cultivating the 100 films began with ASC members each submitting 10 to 25 titles that were personally inspirational or changed the way they approached their craft. “I asked them — as cinematographers, members of the ASC, artists, filmmakers, and people who love film and whose lives were shaped by films — to list the films that were most influential,” Fierberg explains. A master list was then compiled, and members voted on what they considered to be the most essential 100 titles.

The final list includes a Top 10 that was determined by number of votes; the other 90 titles are unranked. “We are trying to call attention to the most significant achievements of the cinematographer’s art,” Fierberg assures. “We do not presume to call one masterful achievement ‘better’ than another.”

“The milestone films are the ones that change everything,” says Steven Poster, ASC. “When they come out, they are extraordinary influencers.” Newton Thomas Sigel, ASC, adds, “Every one of the movies on this list taught me something, and I have tried to steal from virtually each and every one.”

Here, ASC members share their thoughts on many of the films’ lasting legacies.

ASC MASTER CLASSFor more, read this month's 100th Anniversary issue or subscribe now to American CinematographerSubscribe Now Read Digital Edition |

The Top 10

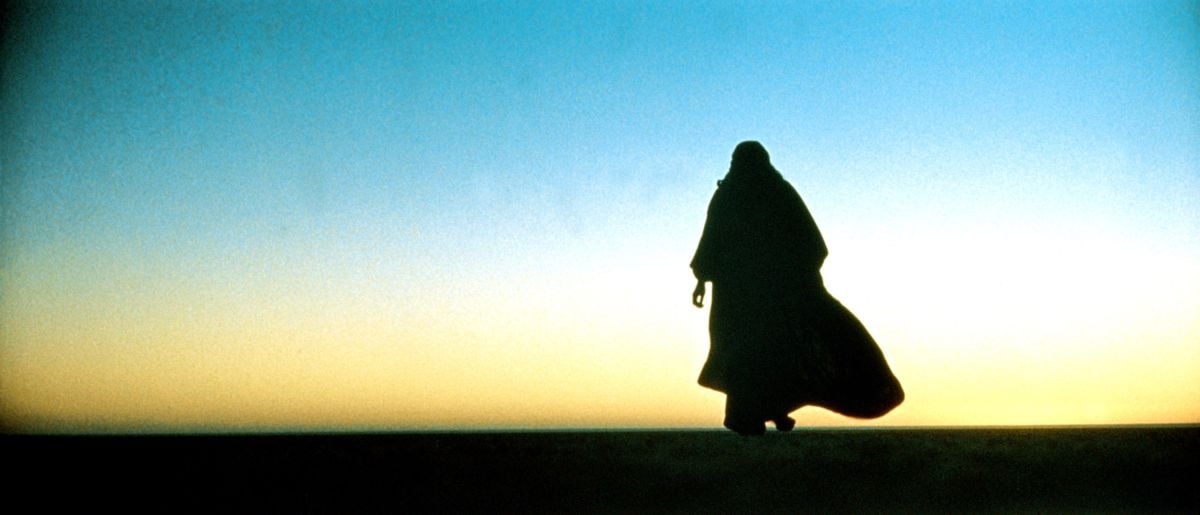

1. Lawrence of Arabia (1962), shot by Freddie Young, BSC (Dir. David Lean)

Phedon Papamichael, ASC, GSC: The first time I saw Lawrence was in the theater in Munich. I was probably 14. I was mesmerized by the epic scope — and although not conscious of any of the technical aspects at that time, I remember how effective it was to have the scenes play out in these stunning wide shots, the characters scaled by the mighty desert. I must have seen this film a dozen times since then, and the power of its cinematic storytelling has not paled. My kids watch it with the same fascination today!

2. Blade Runner (1982), shot by Jordan Cronenweth, ASC (Dir. Ridley Scott)

Daniel Pearl, ASC: Jordan Cronenweth’s [work] totally blew my mind, and it still blows my mind today. I think of it as the turning point, the start of modern cinematography.

Steven Poster, ASC: For years after [its release], everybody referenced Blade Runner. Even if it wasn’t a science-fiction or fantasy movie, that was the reigning style that people wanted, no matter what. I think it influenced an entire generation — not only of filmmakers, but of filmgoers. In every respect, it defined modern film noir. It gave us something to define both the future and the past, all at once. It’s extraordinary to be able to do that.

![In Blade Runner (1982), Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford) finds himself drawn to the mysterious replicant Rachael (Sean Young). One of the identifying characteristics of replicants is a strange glowing quality of the eyes. Cinematographer Jordan Cronenweth, ASC revealed his technique in American Cinematographer: “We'd use a two-way mirror ― 50% transmission, 50% transmission, 50% reflection ― placed in front of the [camera] lens at a 45 degree angle. Then we'd project a light into the mirror so that it would be reflected into the eyes of the subject along the optical axis of the lens. Sometimes we'd use very subtle colored gels to add color to the eyes.”](/imager/uploads/76426/Blade-Runner-1_6c0c164bd2b597ee32b68b8b5755bd2e.jpg)

3. Apocalypse Now (1979), shot by Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC (Dir. Francis Ford Coppola)

Newton Thomas Sigel, ASC: The movie continues to amaze me as much as it did the first time I watched it. It is as current as any film could be. Apocalypse works on every level — aesthetically, dramatically and psychologically. The torture Coppola went through making the movie is seen in every frame.

Mat Beck, ASC: If I had to choose one shot that made me almost want to cry because of how extraordinary it was, it would be from Apocalypse Now, the scene when the upriver camp is under attack. The explosions are going off, and [you can see] the lights on the bridge reflected in the water as the boat accelerates. A beautiful version of hell. It’s one of the most extraordinary visual experiences I can imagine.

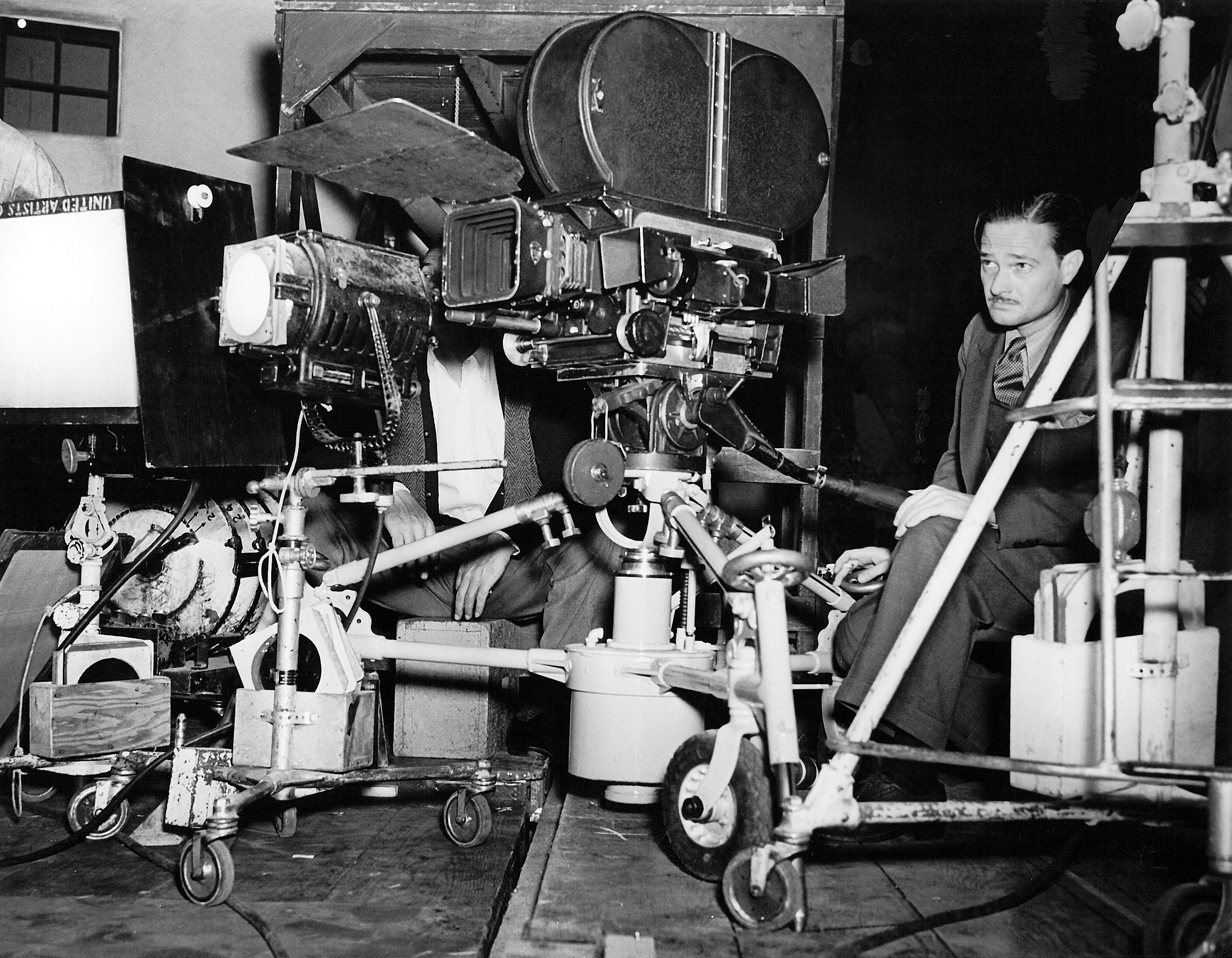

4. Citizen Kane (1941), shot by Gregg Toland, ASC (Dir. Orson Welles)

James Neihouse, ASC: Toland’s work on Citizen Kane has always amazed me. The things he did to achieve those deep-focus images are incredible, and to do it with the film stock, lens technology, and compositing techniques of the early 1940s makes it even more amazing. But there is more to the film than deep focus. The combination of Toland’s composition and camera placement with Welles’ blocking allows the story to play out without the need of cutting. Add to that the innovative way they moved the camera, again allowing the scene to play with a minimum of edits. While not new to filmmaking, all these techniques were masterfully combined and used to move the story along, not just for show. I would have loved to see what Toland and Welles would have done on an Imax screen.

5. The Godfather (1972), shot by Gordon Willis, ASC (Dir. Francis Ford Coppola)

Rachel Morrison, ASC: Believe it or not, The Godfather was a huge influence on Black Panther. The themes overlap — the issue of family and legacy, and the responsibility of power. But of course it’s Gordon Willis’ evocative cinematography that taught me that shadow has as much power as light, and that what is not seen engages the audience in a truly profound way.

Tobias Schliessler, ASC: The Godfather was one of the first movies that showed me the possibility of breaking cinematography’s ‘rules.’ In film school, we were taught to always light an actor’s eyes in order to see their emotions, but Gordon Willis made the artistic choice that perhaps not seeing a character’s emotions was more beneficial to the story. By primarily utilizing toplight, he keeps Marlon Brando’s Don Corleone character mysterious and intimidating. You can’t see what he is thinking or feeling, which enhances the tension and anxiety one might feel in the presence of that character. The Godfather taught how important it is to light for the story, even if that means making an unconventional choice.

Richard Crudo, ASC: Gordon Willis’ work was dark where it needed to be dark. The truth is that parts of his work appear dark because they’re played against other parts which are not. Take, for example, the opening scenes in Don Corleone’s office — dark, foreboding, mysterious. Then, compare it to the bright, overexposed, cheery wedding scene against which the office material is cross-cut. By providing such dramatic and recognizable contrast, each exaggerates the effect of the other. Most important of all, they’re both appropriate within the context of what he was trying to do visually at the time, to help the story along.

Christopher Chomyn, ASC: The Godfather, for me, represents perfect storytelling. No unnecessary dialogue or exposition; all that was necessary to know was revealed in the course of the unfolding drama. The camera movement and lighting perfectly set the tone and kept me engrossed. The bold lighting taught me never to be afraid of the dark, and to use contrast.

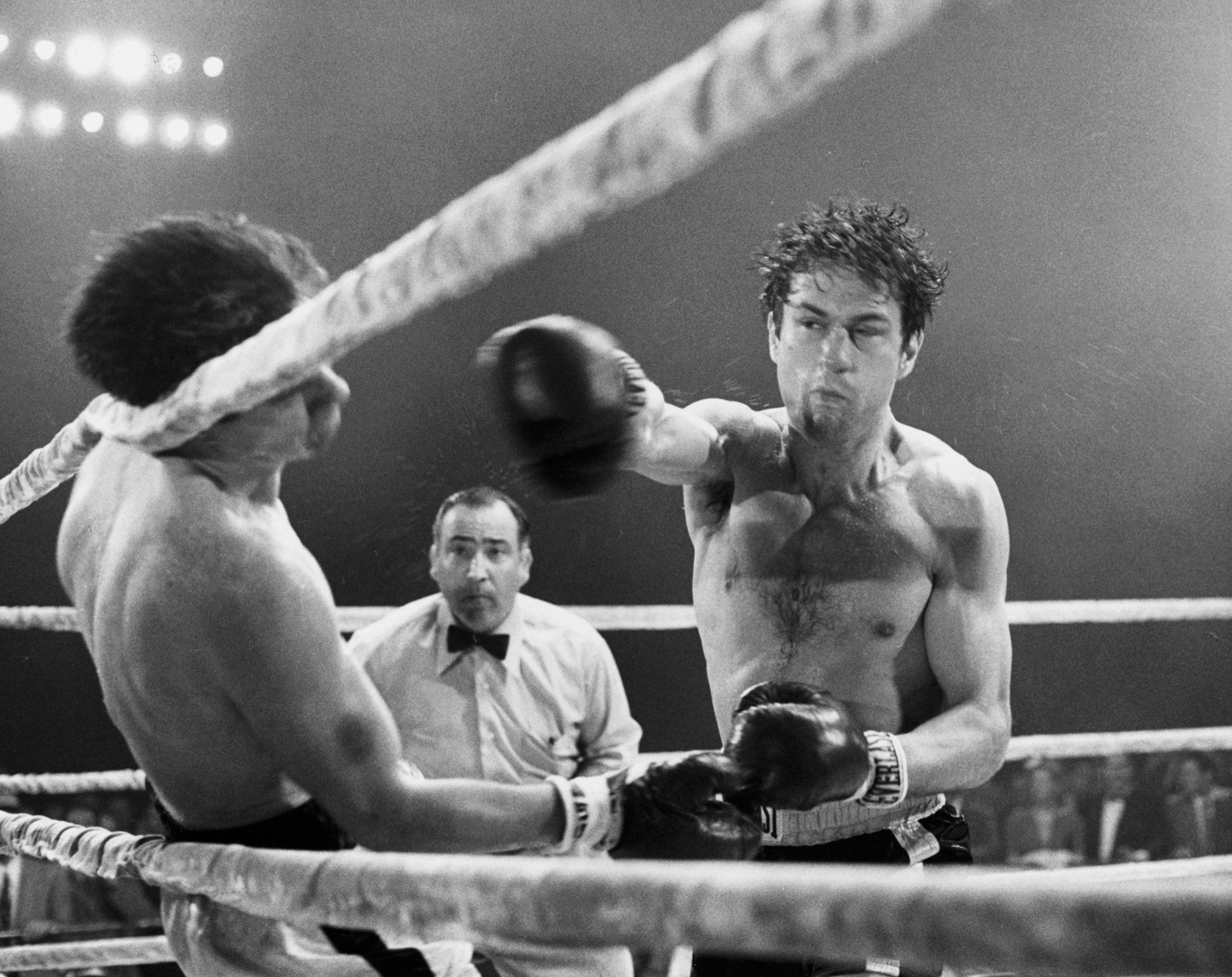

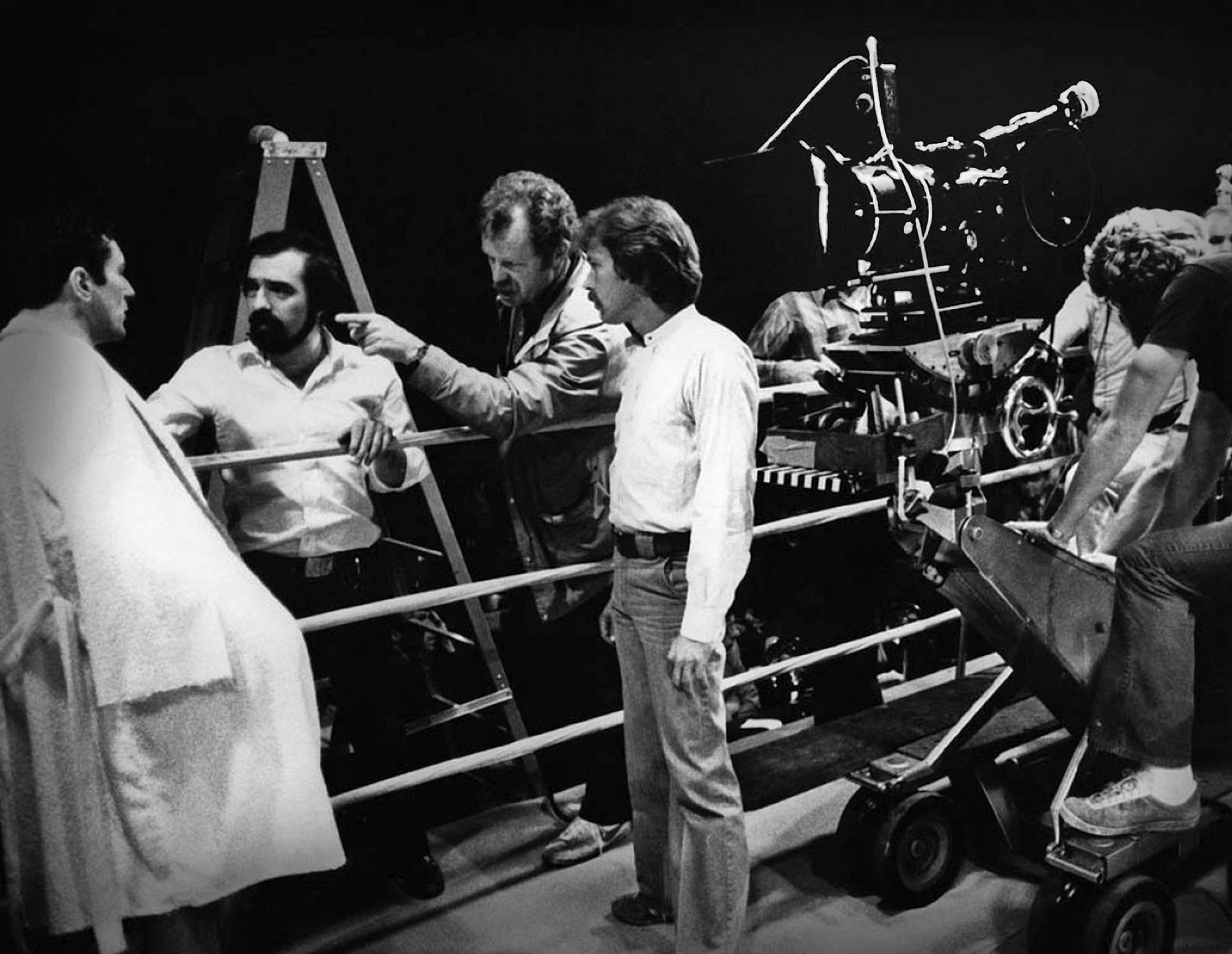

6. Raging Bull (1980), shot by Michael Chapman, ASC (Dir. Martin Scorsese)

Crudo: There’s a tabloid immediacy and a simplicity to Raging Bull that’s fascinating. As cinematographers, everything we try to create comes down to what’s on the page. We’re trying to interpret what the director is thinking, what their approach is to the story. And when you look at the characters in this movie, there’s hardly anyone to identify with. Its themes are hard ones, so the photography is brutal and uncompromising — like a punch in the face, appropriately enough. And Chapman was doing the best job of cinematography just by serving the story. He put the viewer into the narrative in such a way that he made them forget they were watching a movie. He raked up emotion, which is the ultimate success for a filmmaker.

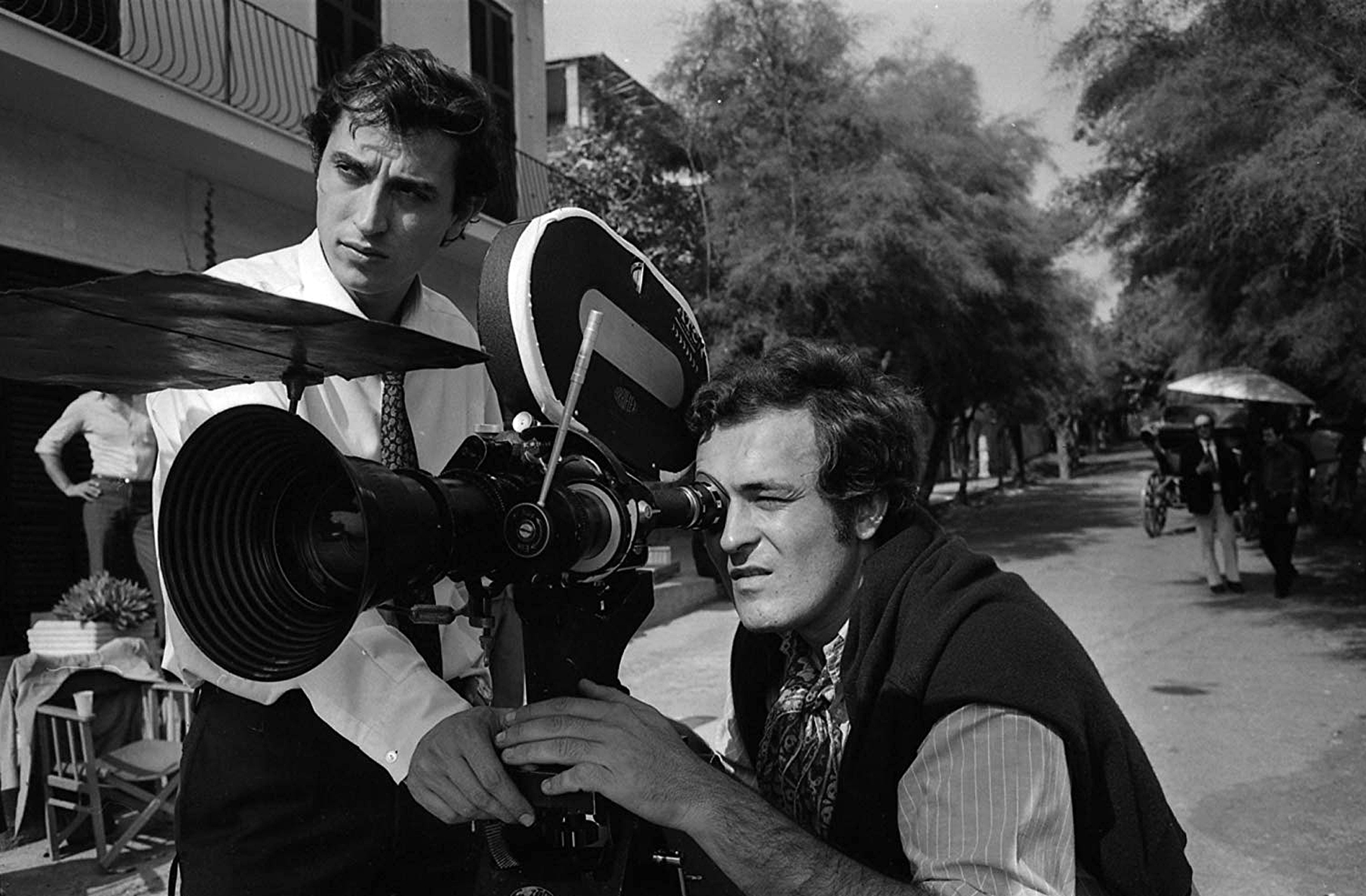

7. The Conformist (1970), shot by Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC (Dir. Bernardo Bertolucci)

Jacek Laskus, ASC, PSC: The Conformist was an eye-opener for me. It threw out everything I knew about cinematography — or everything I thought I knew! It changed the way that I think about cinematography. The use of color, the use of the camera, the movement — it was a tour-de-force for Vittorio. I cannot think of The Conformist being shot any other way.

Papamichael: The Conformist was a key film for me in terms of consciously noticing stylistic lighting, mixing warm practicals with dusky blue day ambience. Vittorio’s use of expressionistic light patterns and painterly, warm sunbeams, and Bertolucci’s wide, composed tracking shots and graphic tableaux, all encouraged me to take risks and attempt bold choices as I was discovering and experimenting, finding a style on my early feature work.

Schliessler: The Conformist has been one of the most influential movies for me and my craft. Every frame is a piece of art that stands alone like a beautiful painting I would want to hang on my wall. I love revisiting this film and drawing inspiration from Storaro’s brilliant use of composition and lighting to enhance the story. His cinematography sets the bar high and encourages me to challenge my own creativity.

8. Days of Heaven (1978), shot by Néstor Almendros, ASC (Dir. Terrence Malick)

Robert Primes, ASC: I was unprepared for the profoundly immersive images that elevated my consciousness into the euphoria generally reserved for Bach or Beethoven. I had always suspected that cinema had the potential to become independent of story and become more like visual music. Days of Heaven, with its minimalist story, felt like being in a gallery of the greatest impressionist masterpieces. It transcended what I had presumed were the apparent bounds of conventional cinema. It moved the art of cinematography from being a supporting player to being the star attraction.

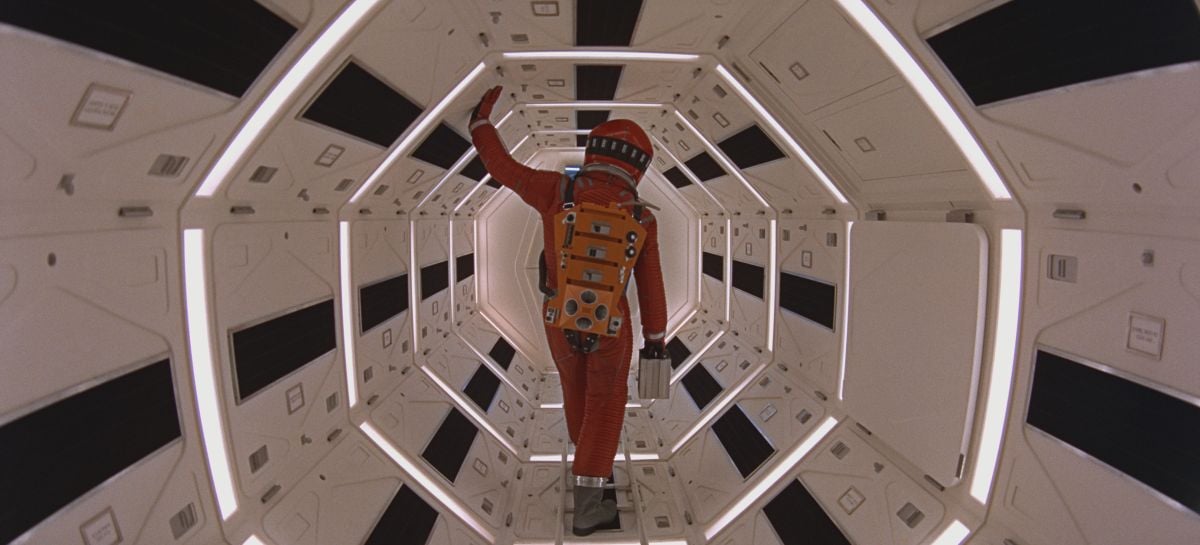

9. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), shot by Geoffrey Unsworth, BSC, with additional photography by John Alcott, BSC (Dir. Stanley Kubrick)

Sigel: I saw 2001: A Space Odyssey as a youngster and had no idea what it was about. But I did know I had been transported to a place only cinema could take me. It was the first time I realized there was an outlet for my compulsion to create.

Steven Fierberg, ASC: I’m so in awe of it, I don’t even know how to discuss it. It’s transcendent. It’s visual poetry on an infinite scale. You have to see it in a theater, either in 70mm or with a really big screen, to see how truly great it is.

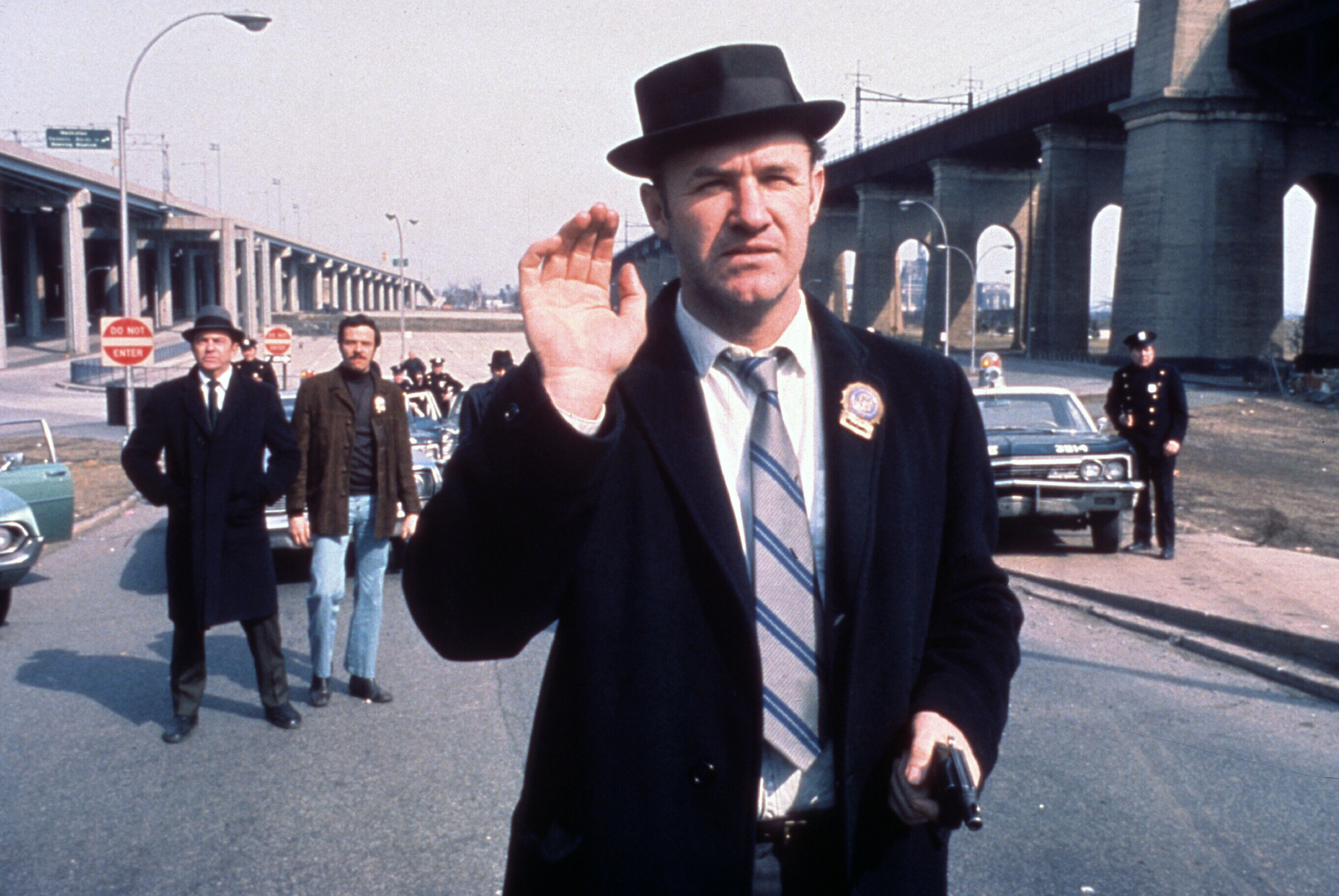

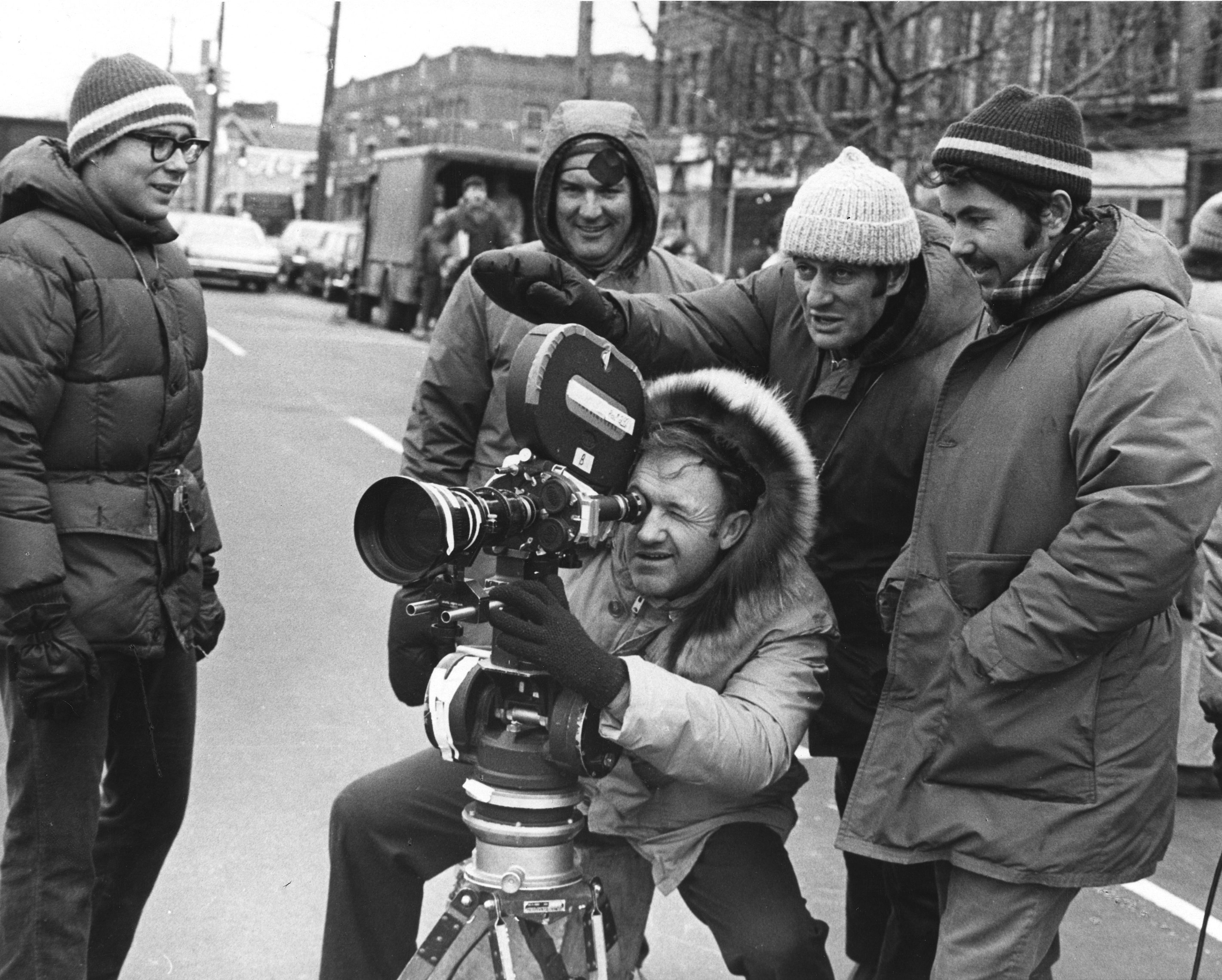

10. The French Connection (1971), shot by Owen Roizman, ASC (Dir. William Friedkin)

Crudo: The French Connection is the leanest form of moviemaking you can imagine. In terms of its visuals, it doesn’t have an ounce of spare fat on it. It gets the information to you absent any sort of artifice. And it’s a cool-toned New York movie. It is such a snapshot of the time. People who didn’t live through it will never know how absolutely faithful to that moment that movie is. Can you imagine being responsible for photographing a major studio motion picture at the time, and the nerve it took to say, ‘You know what? We’re gonna go out and make this thing like real life. Really like real life — not Hollywood backlot real life.’ What an achievement.

Fierberg: The French Connection is supposed to feel ripped from the streets — like, ‘Wow, that really happened. There’s nothing fake here.’ William Friedkin and Owen Roizman, together, were not afraid to do any [kind of] shot. All the things that people are never supposed to do — zoom in, whip-pan, cut across the line — they showed that you could break every rule. And in a story that is really relentless and fast-moving and clearly thought out, it all worked. When you do that kind of cinematography, it makes the movie better because it strengthens it at its core. When you do the kinds of things that Owen Roizman does, it gives an inner strength to the movie in a way that the viewer is unaware of. That’s one of the many reasons I admire him so much.

Titles 11–100

(in order of release)

Metropolis (1927), shot by Karl Freund, ASC; Günther Rittau

Napoleon (1927), shot by Leonce-Henri Burel, Jules Kruger, Joseph-Louis Mundwiller

Sunrise (1927), shot by Charles Rosher Sr., ASC; Karl Struss, ASC

Gone with the Wind (1939), shot by Ernest Haller, ASC

The Wizard of Oz (1939), shot by Harold Rosson, ASC (more here)

The Grapes of Wrath (1940), shot by Gregg Toland, ASC

How Green Was My Valley (1941), shot by Arthur C. Miller, ASC

Casablanca (1942), shot by Arthur Edeson, ASC (more here)

Steven Shaw, ASC: There is one moment in Casablanca when Ingrid Bergman walks into the bar late at night, and it’s closed, and Bogart is there, [wallowing in] the blues, drinking whiskey — and she asks her former lover to give her and her husband a pass to get out of Casablanca and away from the Germans. That close-up, that moment, is, to me, the most beautiful close-up ever shot — it’s beyond beautiful.

I love Casablanca. The trickeries of the lighting — the airport that doesn’t exist. It’s on stage. You feel the airport’s presence, because they’re panning a spotlight through the background. That airport had such a dynamic emotional element to it, and you feel the panic of not being able to escape, and it’s just a spotlight! It’s like magic. It’s one of the great lessons in lighting.

The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), shot by Stanley Cortez, ASC

Black Narcissus (1947), shot by Jack Cardiff, BSC

The Bicycle Thief (1948), shot by Carlo Montuori

The Red Shoes (1948), shot by Jack Cardiff, BSC

The Third Man (1949), shot by Robert Krasker, BSC

Alexander Gruszynski, ASC: I love The Third Man. The camera angles and the lighting are the crucial components of how the story is told. If you take away the visual elements, the story wouldn’t be as powerful — and I think this is a requirement for a milestone of cinematography. This is where all the kudos go to the film’s cinematographer, Robert Krasker, BSC. The famous scene when we first see Orson Welles’ character, Harry Lime, drowned in shadow — you don’t see his face at all, just a pair of shoes and the cat. Then all of a sudden, a neighbor in the building turns on the light and we see Harry Lime for the first time. It’s told with the lighting and the camera. The Third Man is the gold standard for film-noir cinema. It’s the most important film, I would say, in the whole noir genre.

Rashomon (1950) shot by Kazuo Miyagawa

Sunset Boulevard (1950), shot by John Seitz, ASC (more here)

On the Waterfront (1954), shot by Boris Kaufman, ASC

Seven Samurai (1954), shot by Asakazu Nakai

The Night of the Hunter (1955), shot by Stanley Cortez, ASC (more here)

The Searchers (1956), shot by Winton C. Hoch, ASC

The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957), shot by Jack HIldyard, BSC

Touch of Evil (1958), shot by Russell Metty, ASC

Vertigo (1958), shot by Robert Burks, ASC (more here)

North by Northwest (1959), shot by Robert Burks, ASC (more here)

Breathless (1960), shot by Raoul Coutard

Last Year at Marienbad (1961), shot by Sacha Vierny

8 ½ (1963), shot by Gianni Di Venanzo

Hud (1963), shot by James Wong Howe, ASC (more here)

Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), shot by Gilbert Taylor, BSC

I Am Cuba (Soy Cuba; 1964), shot by Sergei Urusevsky (more here)

Natasha Braier, ASC, ADF: There are shots in I Am Cuba that made cinematic history, and the most famous of these is the funeral procession [for a student who had joined the revolution]. I think it [epitomizes] everything that is amazing about this film — how they can do acrobatics with the camera and [accomplish] great technical achievements for that time, but in service to the film’s language, and to a message, and in a way that actually serves the story.

They didn’t have cranes or drones, yet the camera elevates and does all of these acrobatics. They had to create this whole system, where the operator wore a vest with a lot of hooks, and [crewmembers] were hooking him and unhooking him, and lifting him, and making him fly — with very simple means. The sequence starts with the camera on ground level, at a wide angle only a few inches from a young woman, so you really feel like you’re at this ‘human’ level. But then the camera starts to lift up vertically, and then horizontally to enter the third floor of a tobacco factory. It goes through the interior of that floor, and as if the shot wasn’t spectacular enough — especially for the time — the camera travels through [another] window and flies over the street, where you see a top shot of the procession. You’re now three stories high, and you see hundreds of people around the body, walking through the street, and the camera keeps flying above them.

To do all of that in one single take — on film, in the 1960s in Cuba, with such limited technology — is amazing, but it’s not just a technical stunt. The film’s language, acrobatics and camera stunts come together in this shot to tell that story. It touches all the elements that it needs to touch during the shot, going from the individual, to the collective, to the group of workers, to the big collective, which is almost like a wide shot of Cuba itself. It doesn’t make any sense to have a spectacular shot if it doesn’t have a meaning and a purpose behind it.

Doctor Zhivago (1965), shot by Freddie Young, BSC

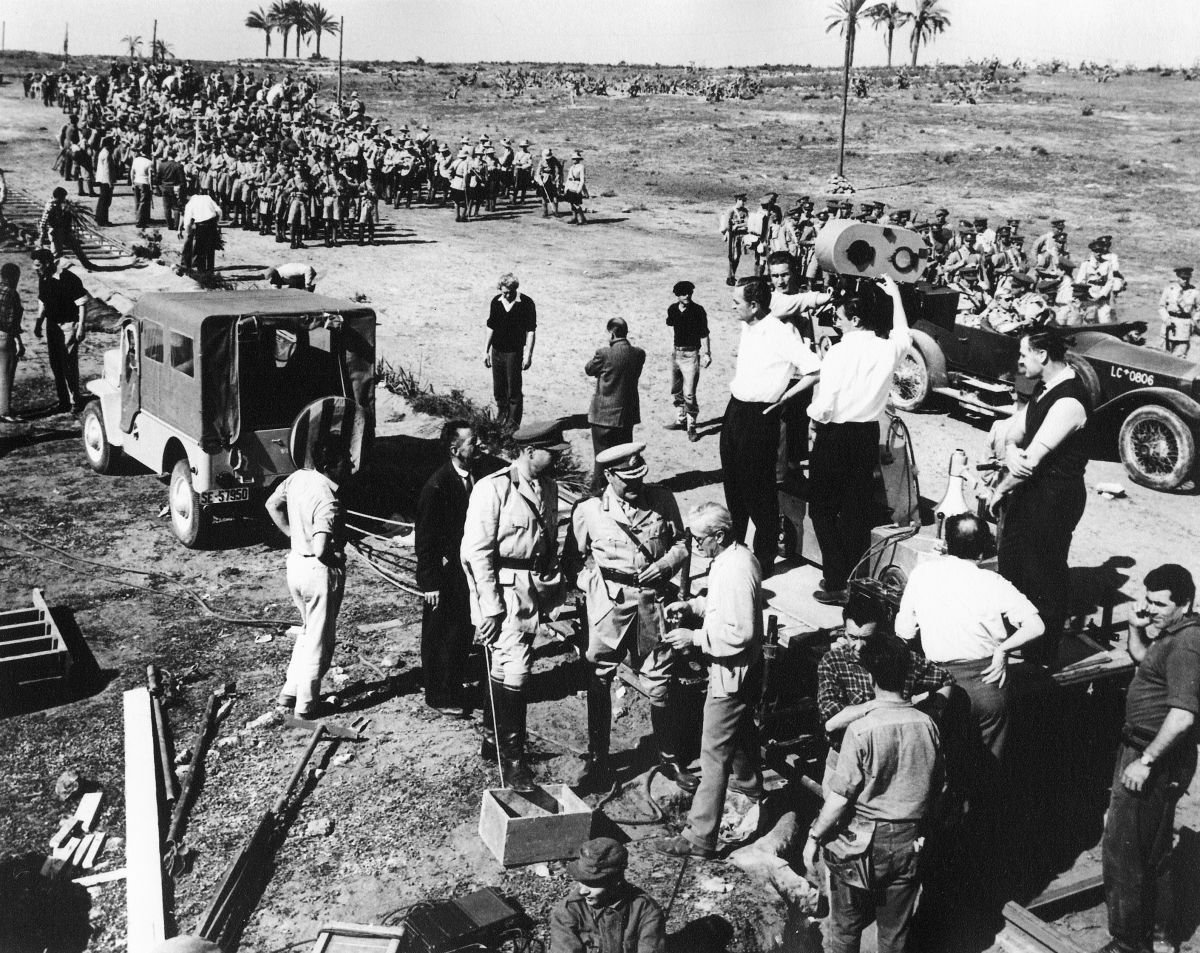

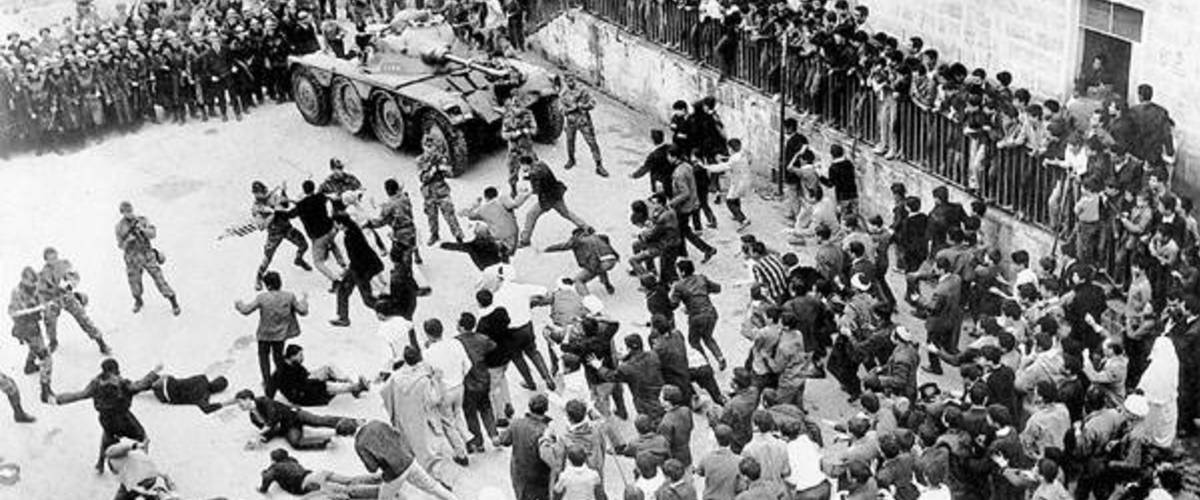

The Battle of Algiers (1966), shot by Marcello Gatti

Chris Menges, ASC, BSC: The Battle of Algiers is a startling and brilliant film about the Algerian war for independence from France. Shot in black-and-white, there are the most amazing re-created scenes of the struggle in the Casbah, the citadel of Algiers, with thousands of extras. There are scenes in which the tension is so powerful, scenes so moving, that you want to cry out. It is filmmaking at its greatest.

Cinematographer Marcello Gatti wheels the handheld camera to catch the moment. [Director] Gillo Pontecorvo lets the shots develop, never using the classical-editing reverse-shot technique. It’s inspired newsreel style: in black-and-white, with documentary-type editing to add to its sense of historical authenticity. The technique is enthralling.

Pontecorvo said, ‘My idea was to give the audience the impression that it was watching a documentary as events happened. We wanted our film to look like newsreel that looked grainy. Using a handheld camera let us spontaneously catch interesting faces and action.’

A superb film — it lives!

Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966), shot by Haskell Wexler, ASC

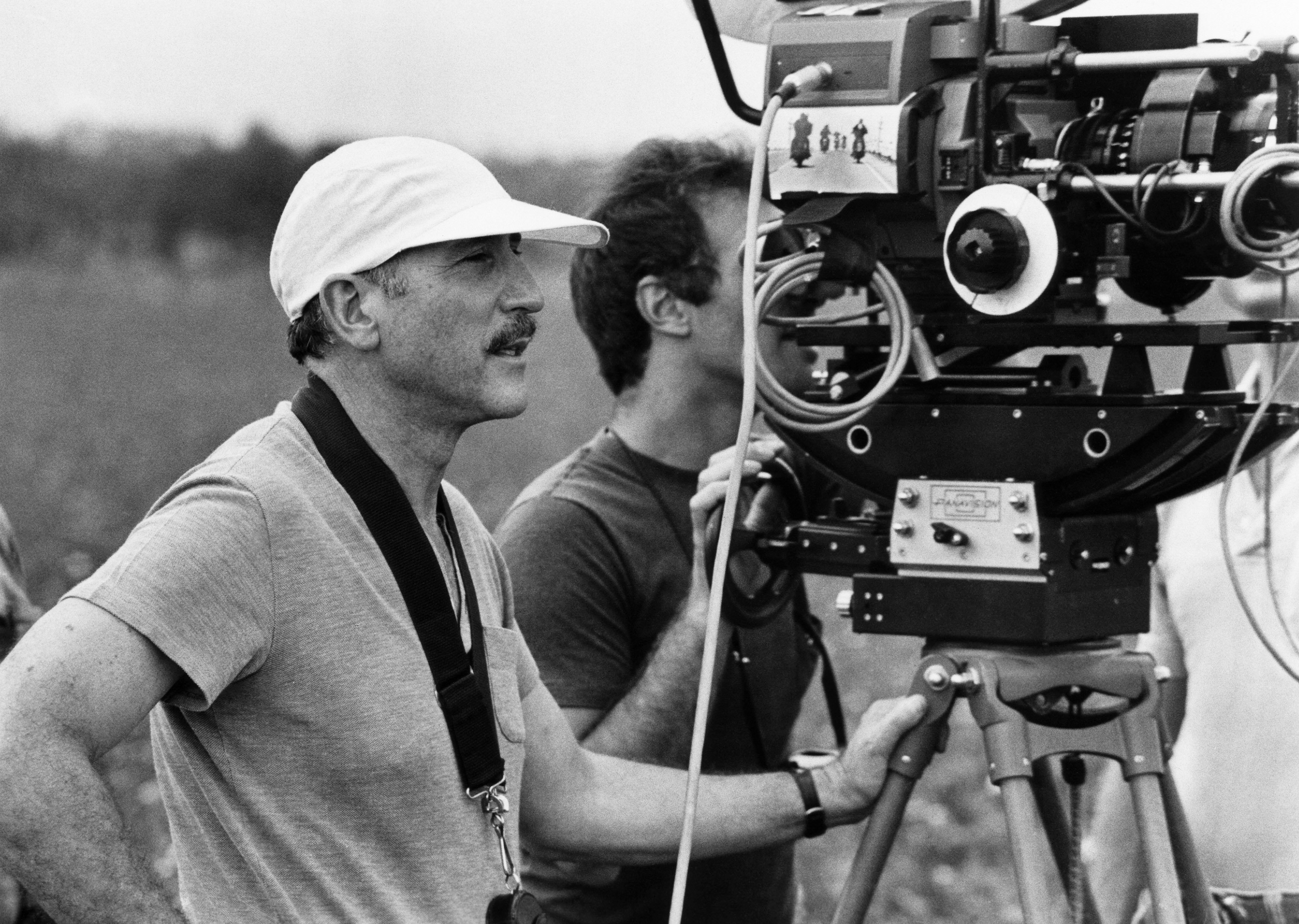

Cool Hand Luke (1967), shot by Conrad Hall, ASC

The Graduate (1967), shot by Robert Surtees, ASC

Michael Goi, ASC, ISC: I saw The Graduate when I was 8 years old, and I couldn’t believe how it made me feel. I realized ultimately that it was the cinematography that did that. Robert Surtees, ASC immediately became my hero. He had been the premier cameraman at MGM, had shot big movies like Ben-Hur, and when technology was changing, when new lightweight cameras were coming, he embraced it — and he worked with all the new, young directors when he was in his 70s.

In Cold Blood (1967), shot by Conrad Hall, ASC (more here)

Once Upon a Time in the West (1968), shot by Tonino Delli Colli, AIC (more here)

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969), shot by Conrad Hall, ASC

The Wild Bunch (1969), shot by Lucien Ballard, ASC

A Clockwork Orange (1971), shot by John Alcott, BSC (more here)

Klute (1971), shot by Gordon Willis, ASC

The Last Picture Show (1971), shot by Robert Surtees, ASC

McCabe and Mrs. Miller (1971), shot by Vilmos Zsigmond, ASC, HSC

Mat Beck, ASC: In terms of my all-time favorite movies, in which the look and sound of the movie carry me into another world, McCabe & Mrs. Miller is such an extraordinary piece of work. When I first saw it, I just loved it — but I didn’t appreciate, as much as I later came to, how beautiful the photography was, and how important it was. It was such an otherworldly experience, and yet so real. It was like an extremely real dream, so I wasn’t thinking too much about how they’d gone about doing it. That movie is a masterpiece, and the photography is of a piece with it, creating a world.

Cabaret (1972), shot by Geoffery Unsworth, BSC

Last Tango in Paris (1972), shot by Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC

The Exorcist (1973), shot by Owen Roizman, ASC (more here)

Chinatown (1974), shot by John A. Alonzo, ASC (more here)

The Godfather: Part II (1974), shot by Gordon Willis, ASC

Barry Lyndon (1975), shot by John Alcott, BSC (more here)

One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1975), shot by Haskell Wexler, ASC

All the President's Men (1976), shot by Gordon Willis, ASC (more here)

Taxi Driver (1976), shot by Michael Chapman, ASC

Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), shot by Vilmos Zsigmond, ASC, HSC

Steven Poster, ASC: Close Encounters of the Third Kind [featured] the largest set ever built indoors for a movie, and Vilmos [Zsigmond, ASC, HSC] — who was a romantic realist, in my opinion — photographed it with such a sure hand, and in a way that no matter what was happening on the set, no matter how difficult the situation was, he pushed forward and did a remarkable job of telling that story. It had a personal quality that, for a movie of that size and complexity, was unprecedented. It was an extraordinary feat.

The Duellists (1977), shot by Frank Tidy, BSC

The Deer Hunter (1978), shot by Vilmos Zsigmond, ASC, HSC (more here)

Alien (1979), shot by Derek Vanlint, CSC (more here, here and here)

All that Jazz (1979), shot by Giuseppe Rotunno, ASC, AIC

Being There (1979), shot by Caleb Deschanel, ASC

The Black Stallion (1979), shot by Caleb Deschanel, ASC

Manhattan (1979), shot by Gordon Willis, ASC

The Shining (1980), shot by John Alcott, BSC (more here)

Chariots of Fire (1981), shot by David Watkin, BSC

Das Boot (1981), shot by Jost Vacano, ASC

Reds (1981), shot by Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC

Fanny and Alexander (1982), shot by Sven Nykvist, ASC

The Right Stuff (1983), shot by Caleb Deschanel, ASC

Amadeus (1984), shot by Miroslav Ondricek, ASC, ACK

The Natural (1984), shot by Caleb Deschanel, ASC

Paris, Texas (1984), shot by Robby Müller, NSC, BVK

Brazil (1985), shot by Roger Pratt, BSC

The Mission (1986), shot by Chris Menges, ASC, BSC

Empire of the Sun (1987), shot by Allen Daviau, ASC

The Last Emperor (1987), shot by Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC

Wings of Desire (1987), shot by Henri Alekan

Mississippi Burning (1988), shot by Peter Biziou, BSC

JFK (1991), shot by Robert Richardson, ASC

Raise the Red Lantern (1991), shot by Fei Zhao

Unforgiven (1992), shot by Jack Green, ASC (more here)

Baraka (1992), shot by Ron Fricke

Schindler's List (1993), shot by Janusz Kaminski

Searching For Bobby Fischer (1993), shot by Conrad Hall, ASC

Charles Minsky, ASC: From the film’s beginning, Conrad Hall, ASC’s cinematography in Searching for Bobby Fischer is warm and intimate. His use of long lenses enhances this interior, personal story and invites the viewer into the complicated relationships between the characters. The camera is always seeking the heart of the story through the heart of the 7-year old boy at its center. Continually moving in and out of the shadows, the close-ups of the boy, his parents and his teachers reveal the boy’s search for a hero to believe in. The camera doesn’t turn away. Through the boy’s eyes, it makes us confront ourselves. From the beginning close-up of the chessboard, reflected in a pair of sunglasses, to the ending close-up of two 7-year-old boys walking arm in arm away from camera, it maintains a personal and intimate involvement in the boy’s life. It makes us understand that the boy is only a boy.

Trois Coulieurs: Bleu (Three Colours: Blue; 1993), shot by Slawomir Idziak, PSC

The Shawshank Redemption (1994), shot by Roger Deakins, ASC, BSC (more here)

Seven (1995), shot by Darius Khondji, ASC, AFC (more here and here)

The English Patient (1996), shot by John Seale, ASC, ACS

L. A. Confidential (1997), shot by Dante Spinotti, ASC, AIC (more here)

Saving Private Ryan (1998), shot by Janusz Kaminski (more here and here)

The Thin Red Line (1998), shot by John Toll, ASC (more here)

American Beauty (1999), shot by Conrad Hall, ASC

The Matrix (1999), shot by Bill Pope, ASC (more here)

In the Mood for Love (2000), shot by Christopher Doyle, HKSC

As more related content regarding the titles on this list are added to our Historicals section, we'll continue to update this article with new links.