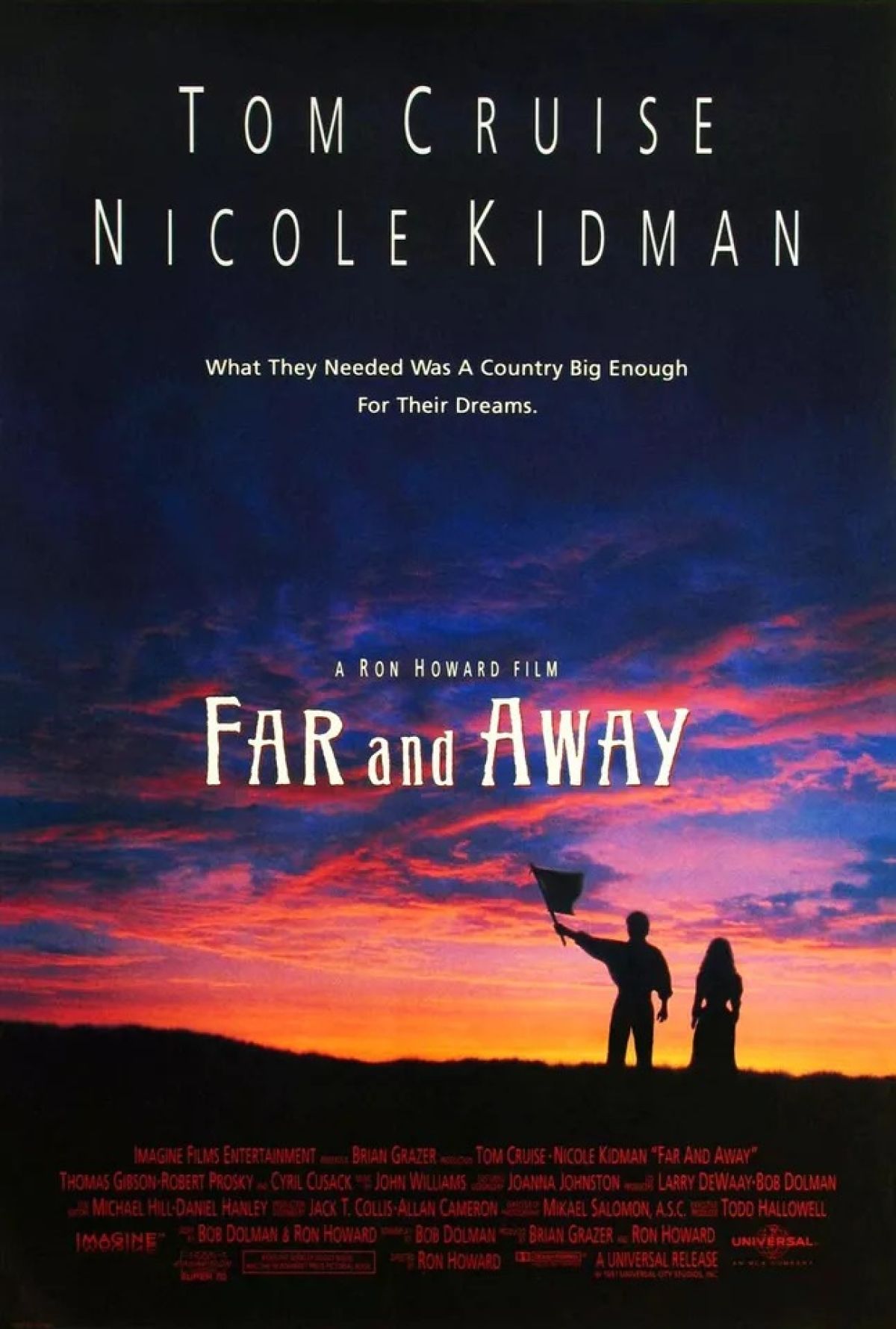

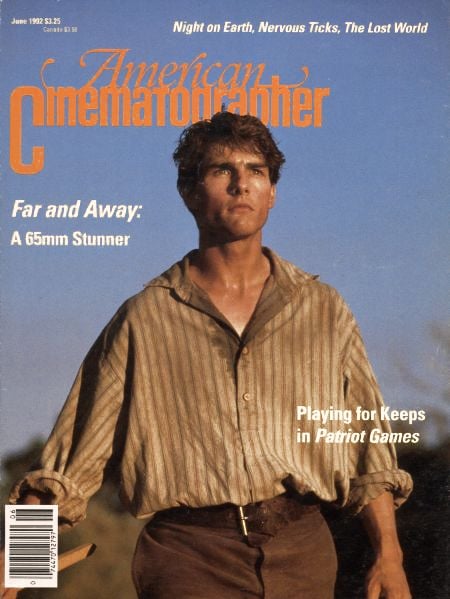

Far and Away: From the Emerald Isle to Big Sky Country

Mikael Salomon, ASC — inspired by the films of his youth — dives into the 65mm pool with the help of Panavision.

Unit photography by Phillip Caruso

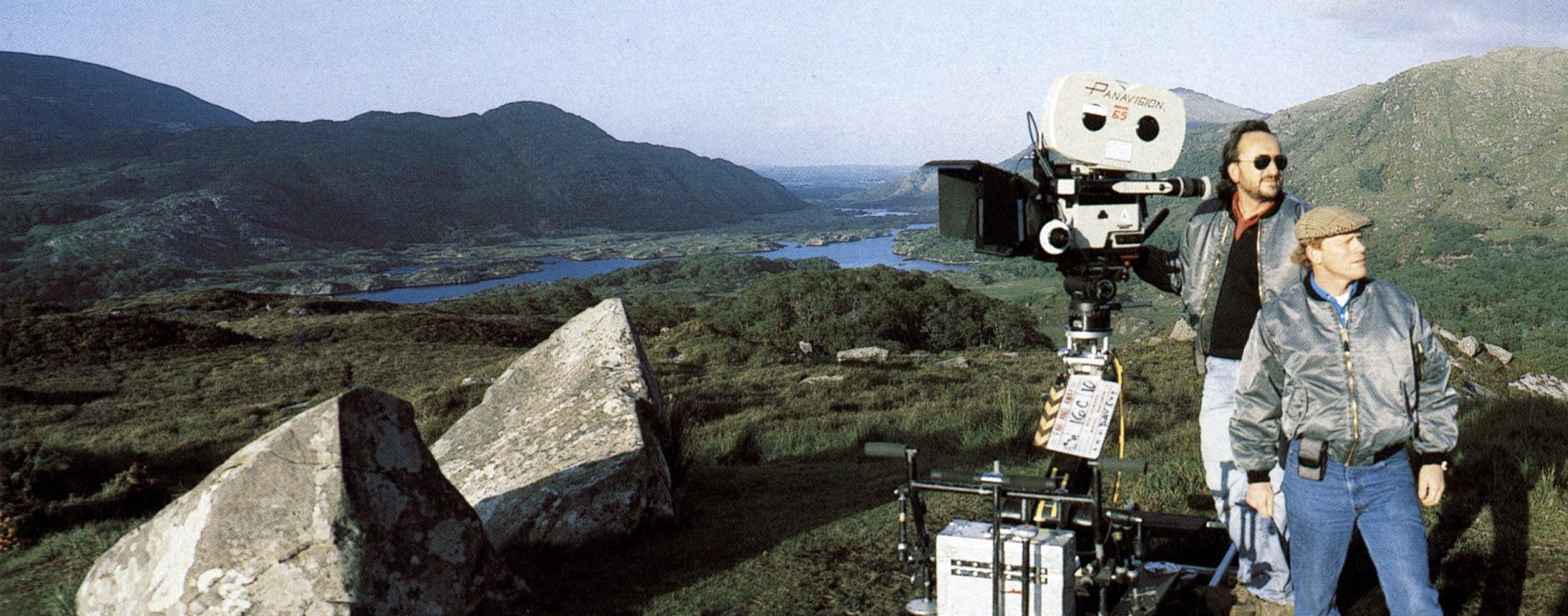

After a hiatus of more than 20 years, the 65mm format is back in theaters with Ron Howard's Far and Away. It's the first theatrical feature produced in the grand format since David Lean and Freddie Young, BSC made Ryan's Daughter in 1969.

Mikael Salomon, ASC has vivid memories of a magical day in 1968 when he and his father traveled from Copenhagen to London for the opening of 2001: A Space Odyssey. A few years later, Young captured Lean's visualization of Ryan's Daughter on film in what turned out to be the last 65mm feature — until now.

For nearly 20 years, “roadshows,” as the large-format films were called, dominated the box office. Between 1952 and 1970, more than 40 wide-format (mainly 65mm) films were produced. In addition to 2001 and Ryan's Daughter, the titles included Oklahoma!, My Fair Lady, Around the World in 80 Days, Lawrence of Arabia, Cleopatra, Ben-Hur, Hello Dolly, The Sound of Music, It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, How the West Was Won, Grand Prix, The Sand Pebbles, Dr. Zhivago, Ice Station Zebra, The Alamo, Exodus and South Pacific.

“Because of the clarity and definition of the 65mm images, I felt we could add a dimension to the story. I believed we could create a more intimate film, which would involve the audience more with the characters and story.”

— director Ron Howard

What went wrong? For starters, there was a nasty recession, and in those days, it cost a lot more to produce films in 65mm format. The cameras were comparatively heavy and cumbersome and the film and lenses were slow. (Prior to Kodak's introduction of a 100-speed color negative film in 1968, the standard color negative had an exposure index of 50.)

Advances in 35mm camera and film technology provided less costly and more flexible alternatives for creating a big-screen experience. Panavision refined high-quality anamorphic lenses that made it possible to squeeze a 35mm image into a widescreen aspect ratio. Around the same time, the image structure of 35mm Eastman color negative film was substantially improved. The result was an ability to shoot in 35mm format and make high-quality 70mm release prints. (Release prints are 5mm wider than the 65mm camera negative in order to accommodate the sound track.)

Ryan's Daughter marked the end of an era, but Salomon never forgot the feeling he had when he saw Stanley Kubrick's 2001. In his heart, the cinematographer believed that he would someday play a part in making films like that again.

“It’s a sweeping adventure story, and I thought the scope of the 65mm film format could add a lot to the way the audience would experience the movie.”

— producer Brian Grazer

During his mid-teens, Salomon worked as a photographer for a youth magazine. When he was 17 a Copenhagen film company asked him if he wanted to shoot a few movies. It was down and dirty work, consisting mainly of industrial and agricultural training films and documentaries. Salomon remembers shooting scenes in barns and stables with a 16mm color positive film that had an exposure index of 16. "You walked onto a set and there were lights everywhere, just to get an exposure," he recalls. "It really made me appreciate what it took for someone like Harry Stradling [ASC] to shoot My Fair Lady.” He segued into features when he was only 20, and compiled some 50 credits during the next several decades, mainly in Scandinavia.

During the mid-1980s, Salomon shot an HBO movie for a U.S. producer he had worked with in Europe. That assignment led to opportunities to shoot Zelly and Me and Torch Song Trilogy, two independent features which attracted critical acclaim. James Cameron then asked Salomon to shoot The Abyss. It was his first big-budget film, and he earned an Oscar nomination for his efforts.

Salomon went on to shoot Always and Arachnophobia, both with Steven Spielberg. "I was content working in Europe," he says. "I wasn't trying to establish myself in the U.S. It just happened."

In 1991, when Salomon was in Chicago working on Backdraft, director Ron Howard told him about a small film he was planning to make about the migration of Irish immigrants to the United States during the 1890s. Howard planned to shoot the film in Europe on a minimal budget, but when Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman were cast in the lead roles, Howard started thinking big.

"I showed him [Salomon] the script, and he loved it," Howard recalls. "Mikael suggested that we shoot Far and Away in 65mm format." How many cinematographers have tried that line on directors during the past 20 years?

Several days after their initial conversation, Howard asked Salomon if there were any drawbacks. Salomon told him it would cost more and that blocking (staging of shots) would have to be more precise to account for the comparatively shallow depth of field inherent to 65mm format lenses.

Howard and producer Brian Grazer, the chairmen of Imagine Films (Splash, Night Shift, Backdraft) mulled it over for a while, then asked Salomon to come up with solid numbers for those additional costs. He conferred with Panavision, Arriflex, Kodak, DeLuxe Labs and other potential vendors. When all the facts were assembled, it turned out that shooting Far and Away in 65mm format would add a small percentage to the overall budget. Next, Salomon shot some tests in 65mm. That was enough to turn Howard and Grazer into true believers.

"I watched Ron and Mikael work together on Backdraft, and it was certainly one of the most visually exciting movies of 1991," Grazer says. "They were doing innovative things with the 35mm camera. I thought they were the right people to make a film like Far and Away in 65mm format. It's a sweeping adventure story, and I thought the scope of the 65mm film format could add a lot to the way the audience would experience the movie."

Howard agrees. "Because of the clarity and definition of the 65mm images, I felt we could add a dimension to the story. I believed we could create a more intimate film, which would involve the audience more with the characters and story. I wanted to totally engross them on a subconscious level."

Howard wanted Far and Away to be an extraordinary film. "I'm a product of the melting pot," he explains. "My ancestors were Dutch, German, English and Cherokee Indian, in addition to Irish. But there has always been something romantic about the Irish part of my heritage." Three of Howard's great-grandfathers had participated in the Cherokee Strip Land Race in Oklahoma in 1893. When he was six, one of his great-grandmothers showed him a scrapbook filled with newspaper clippings and photos of the land race. It made another indelible impression.

In 1983, while Howard was directing a TV movie [Little Shots], he and scriptwriter Bob Dolman discovered they shared a dream about making a film about Ireland. They talked about it for years, but the catalyst turned out to be a casual evening out, where Howard heard a folk group singing traditional Irish songs. He was touched by a tragic lyric about a couple separated when one of them migrated to America, and he started thinking about the experiences his ancestors had when they migrated to the United States.

That's when he decided to make Far and Away. Cruise plays the part of Joseph Donnelly, a tenant farmer's son who attempts to avenge his father's death by killing a landlord he feels is responsible. His plan fails and he becomes a fugitive, linking up with Kidman's Shannon Christie, the daughter of a rich landlord who yearns for adventure and freedom that she believes is hers for the taking in America.

Along with thousands of other Irish immigrants, Joseph and Shannon journey across the ocean to Boston, a city darkened by relentless smoke from coal fires. They share a small room in a boarding house that doubles as a brothel. Joseph ekes out a living by fighting bare-knuckle boxing matches in a social club for working-class Irish immigrants. Eventually, they get caught up in the tide of immigrants flowing west in search of land. The story embraces a spectacular re-creation of the 1893 land race in Oklahoma.

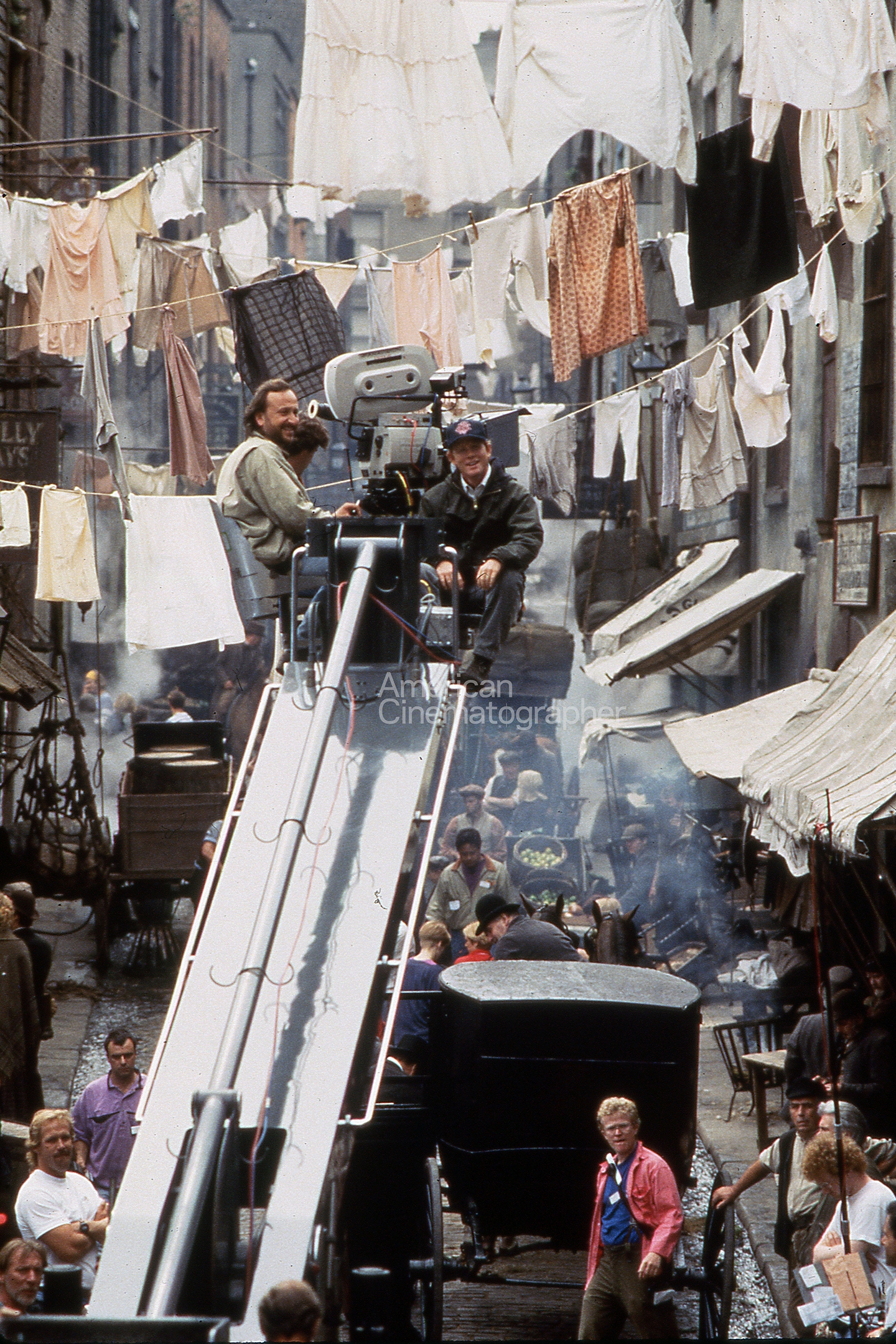

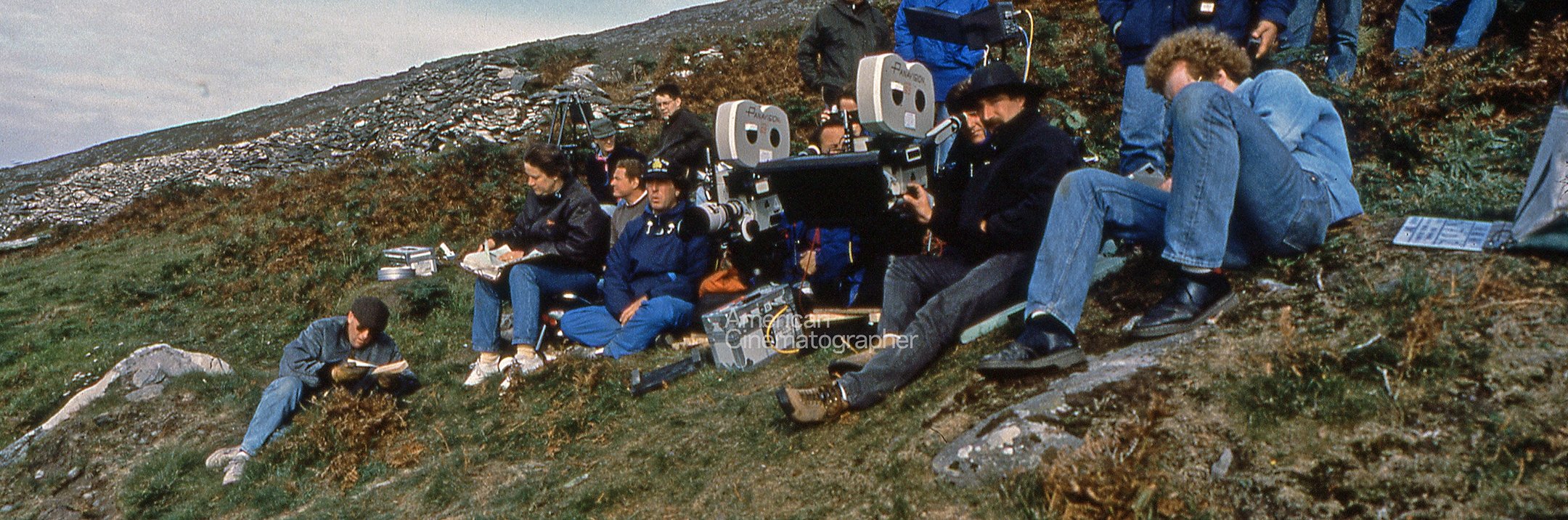

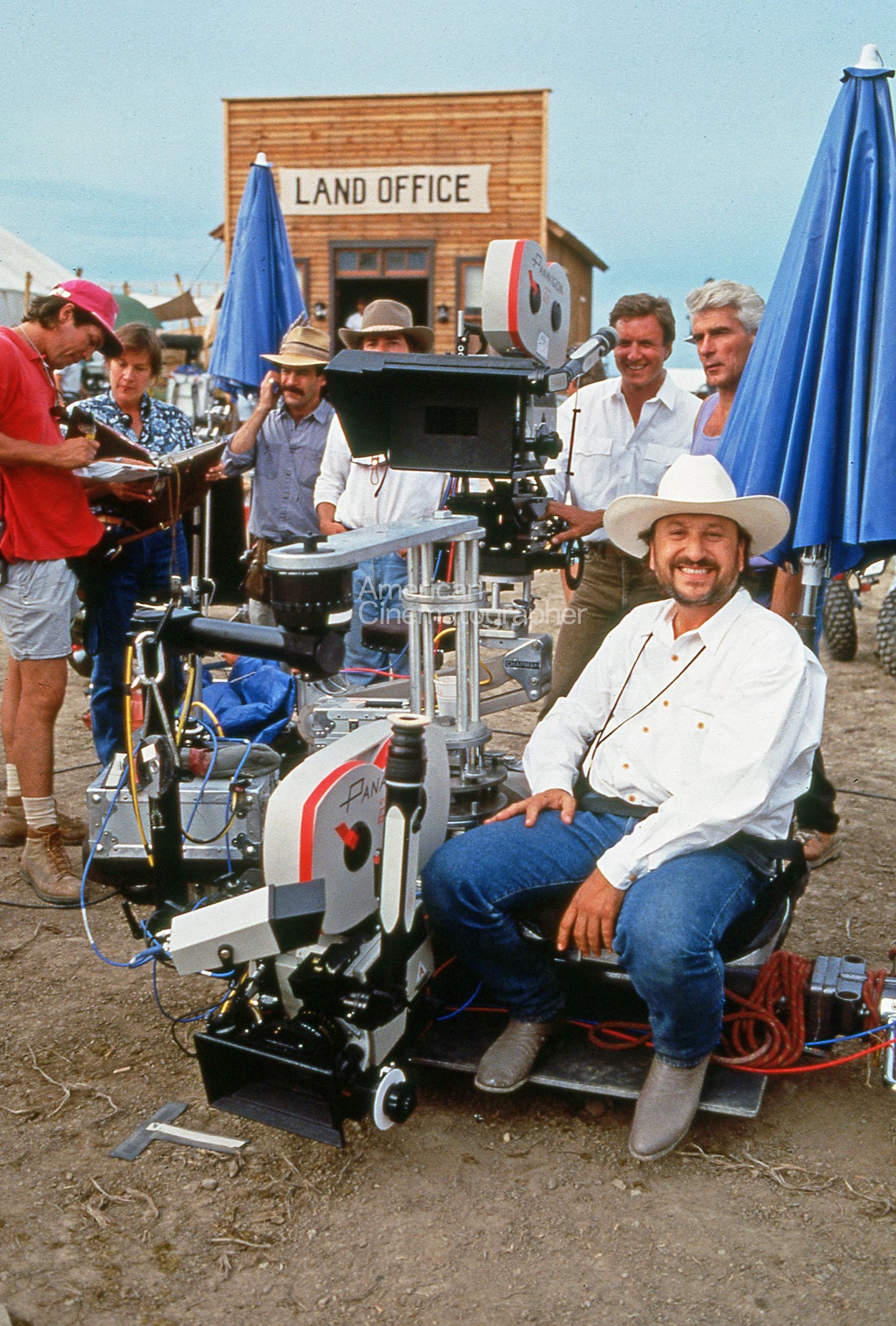

Far and Away was filmed at locations in and around Billings, Montana, and Dublin, Ireland. Montana provided locales with open spaces reminiscent of Oklahoma during the 1890s. A number of interior sets were built in a warehouse. The Ireland scenes and Boston exterior sequences were shot in and around Dublin.

Salomon says that every film defines its own look: "You can't look at what someone else did in 65mm and apply it to another film. You have to be willing to break rules and take chances. That's the only way you can shoot a film that's fresh and interesting."

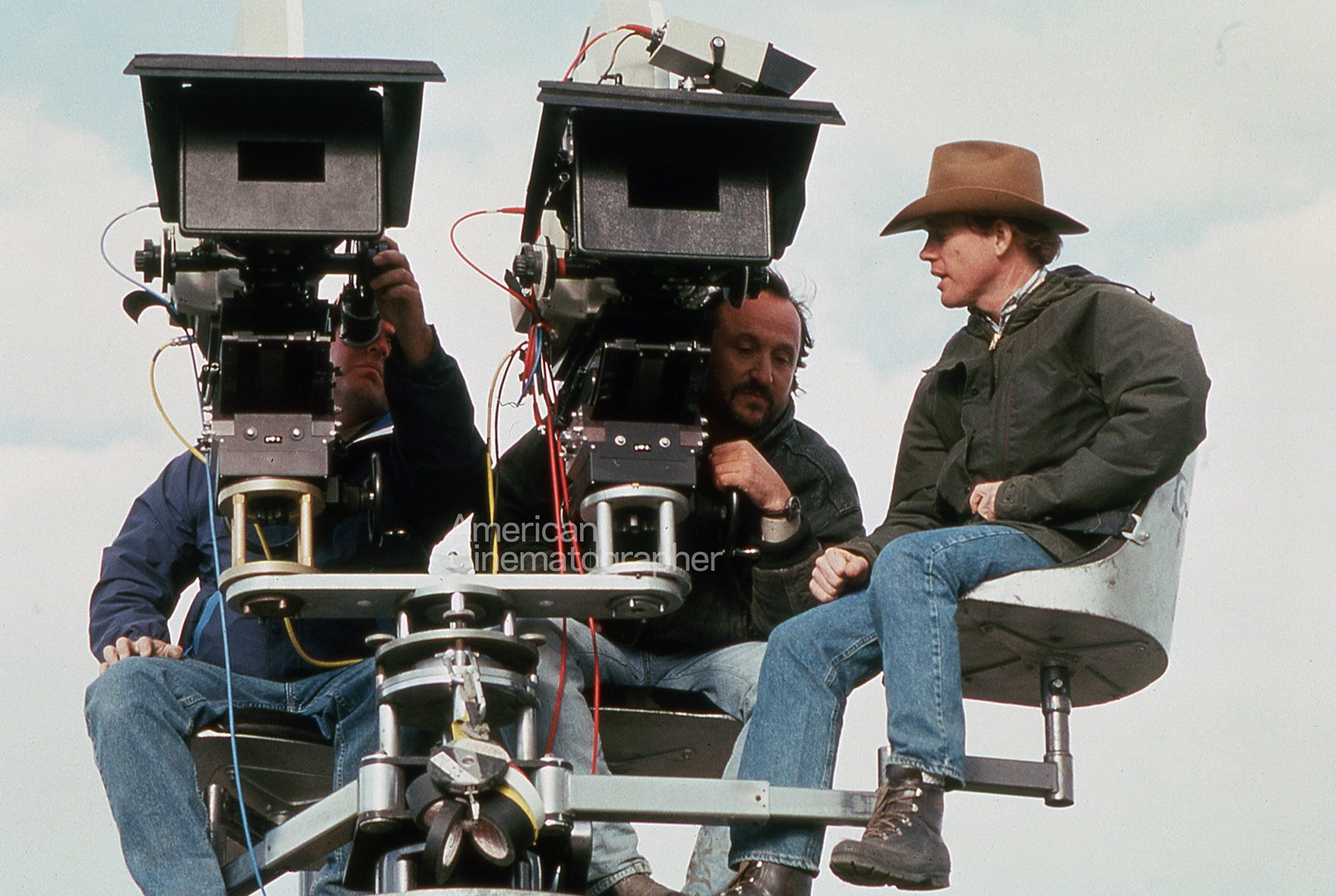

One of the more difficult decisions for Salomon was the choice between the new Arriflex 765 and Panavision Panaflex System 65 Studio camera systems. In addition to the new sound camera, Panavision was able to provide a number of 65mm handheld cameras — lighter-weight retreads from the 1960s. Salomon knew that he would be making frequent use of Steadicams. He needed the handheld cameras for that purpose, and also for additional coverage for scenes he wanted to shoot from multiple perspectives.

Another main consideration was that Panavision is headquartered in Los Angeles, reasonably close to the Montana location where production started. They had technician Don Earl with Salomon from the first through the last day of shooting in Montana. Another Panavision technician was with the crew in Ireland. "I couldn't ask for better support," Salomon says.

Frankly, it wasn't love at first sight between Salomon and the camera. It's a featherweight compared to the 65mm cameras used during the 1950s and 1960s, but it's still 85 pounds with a 1,000-foot magazine on it. In comparison, a 35mm Panaflex camera with a loaded magazine weighs around 36 pounds. "When I first saw it, I thought, 'What a monster. We're going to have to shoot this entire movie at eye level,'" Salomon confesses.

But that concern dissipated. "We had two of the new Panavision 65mm sound cameras, and they were used on dollies most of the time," says Salomon. "There was nothing we couldn't do, no angle we didn't shoot from."

Salomon carried two Steadicam rigs on location and frequently used them with the handheld Panavision cameras to make long tracking shots. Scenes in the social club, for example, were filmed at a practical location in Billings. The fight scenes were claustrophobic: spectators were jammed together shoulder to shoulder, the noise was insistently clamorous, and many people in the crowd were smoking. A murky cloud of smoke hung in the air, diffusing and spreading the light and imprinting a moody texture on the scene

While he covered master shots with a sound camera, one of the handheld cameras was on a Steadicam, which provided a close look at the adversaries. "In those days, fighters stood toe to toe, and hit each other until one of them dropped," Salomon explains. "Joseph had learned how to duck and dodge to avoid blows. That's why he was winning his fights."

Salomon used the Steadicam to pump visual energy into the scene. He moved the camera around and in between the fighters, using the angle of coverage to disguise the fact that the choreographed blows weren't connecting. The mobile camera was operated at up to 72 frames a second, providing a subjective point-of-view in slow motion. A remote camera also looked down on the fight, swooping down when Joseph floored an opponent and rising with him as he got up

Salomon used a broad range of lenses, from 24mm to 800mm. This includes a series of new Panavision 24, 35, 50 75,100, and 150 millimeters, and a 40mm lens that Salomon opted not to use. In addition, there were older 50, 75, 180, 300 and 400mm lenses, along with a Canon zoom lens. In 65mm format, the focal length of a 24mm lens is just about equivalent to a 12mm lens shooting in 35mm format. "One of the locations in Ireland was a mansion, and the only way we could shoot in some rooms was with an ultra-wide lens," he says.

Salomon emphasizes that depth of field is a critical consideration when shooting a 65mm film. The images generally must be crisp and flawless because the audience sees every detail. Films produced in the spherical 1.85:1 aspect ratio in 35mm format don't use some 25 to 30 percent of the 35mm negative area due to the masking. Shorter focal length lenses which offer more depth-of-field can be used. Conversely, the image area on a 65mm film frame is more than four times larger than a 35mm frame. It requires the use of longer focal length lenses with measurably less depth of field.

Salomon generally worked within the range of stop T4 to T5.6. With the zoom lens, which he frequently used, Salomon usually shot wide open at stop T6.3. But there were exceptions. For example, several large night exterior scenes were filmed with the lens opening at T2.8 or 3.5.

"On one big street scene, Ron wanted the audience to see what was happening in the background," Salomon says. "It would have taken an extra half a day to rig enough lights just to give me an extra half-stop. But I was able to shoot with a wider lens opening, hold my blacks, and still pull details out of the shadows in the background. Today's films and lenses gave me the freedom to make those kinds of decisions."

Salomon conjured up distinctly different looks to match the moods and realities of the settings. Ireland was characterized by verdant green foliage and other deeply saturated colors, shot against a background of overcast skies. Boston was dark and moody, lit by kerosene and gas street lights and lanterns, as well as occasional bam fires. Some locations were tacky, dingy and low-key. It was the visual companion to the black mood depicted in that part of the script. Oklahoma was bright, airy and open, with liquid blue skies dressed up by puffs of pure white clouds. The backgrounds seem endlessly deep; it literally looks like the promised land.

Salomon was never tempted to craft a stylized period look. Instead, he relied on costumes, production design, and the use of realistically motivated light sources to recreate the aura of the 1890s in these three distinctly different settings.

Part of the set of the small room that Joseph and Shannon shared in the Boston brothel was a long hallway with many doors, which made the walls heavy and cumbersome to move. A ceiling helped establish the reality of the location, but meant that Salomon had to light through windows, motivated by the moon and sun, and by a single kerosene lamp on the set.

In Ireland, Salomon did it all, shooting day-for-night, and in artificial rain, snow and fog. "Sometimes, we had to adjust to nature," he says. A scene where some tenant farmers are digging a ditch in a torrential rainstorm was shot on one of the few days in Ireland when the sun shone brightly and persistently. If David Lean or Akira Kurosawa were shooting this film 20 years ago, they might have the clout to wait for rain, or for clouds to block the sun. Salomon was much more pragmatic. He used smoke to mask the sunlight, and shot the scene in artificial rain.

For a night exterior scene filmed in an artificial snowstorm on the grounds of a mansion in Ireland, "there were no street lights, and there's no moonlight in a storm. But in the real world, it's rarely totally dark. There's almost always some ambient light in the darkest setting. We created a general ambient light, and printed way down until we could just barely see faces."

Salomon matched four different 65mm film stocks to specific production situations. For example, in a night scene early in the film which takes place in a huge expanse of woods where Joseph is stalking a landlord, Salomon used the Eastman EXR 100T film 5248 without a number 85 filter on the camera lens instead of lighting for a night shot. This gave a colder, darker tone to the film. He also enhanced the effect by underexposing the film by a stop-and-a-half, and by using both smoke and diffusion. There were no obvious sources for motivating light. Normally, Salomon says he would have used the sun as backlight in this situation, but intermittent clouds blocked the sun at random intervals, so Salomon used smoke to mask the sun and created his own backlight.

He generally used the 250-speed Eastman 5297 film for shooting daylight interiors, the 50D film 5245 for daylight exteriors, and the 500T film 5296 for night and darker exterior and interior scenes. At various times, Salomon subtly altered the quality of images with either Harrison LC or Tiffen special effects filters on the camera lens. Big daylight exteriors were generally shot without diffusion.

Those types of decisions require a delicate combination of instinct and experience. "I avoid talking about film speed, because it varies depending on how you read the light meter," he says. "The important thing is the printer light at the lab. I always try to stay in the low 40s. That's how you get rich blacks and a wide range of tonality."

Salomon, with considerable help from Panavision, did a little free-form innovating with the use of lenses. He had a 35mm lens and a 45mm lens modified so he could physically shift the direction of the focal plane from side to side to front to back, and vice versa. This slant focus lens, similar to a split diopter, allowed him to keep both Kidman and Cruise in focus when one was in the foreground and the other in the background without the blurry line that you would get when using a split diopter.

"With a normal lens, shooting in that situation, the foreground or background with either Tom or Nicole would have gone noticeably soft," Salomon says. Use of this lens required precise blocking and flawless execution by the cast. "The alternative is composing scenes with the actors always on the same horizontal plane, and that would have been visually boring."

At other times, Salomon used selective focus as part of the visual grammar of the film. In a small bedroom scene in Boston, Shannon is in the foreground behind a screen looking at Joseph, who is seen full-figure in the background. Both are in crisp focus. Salomon allowed part of the room to go a little soft in order to focus attention on the interaction between the characters.

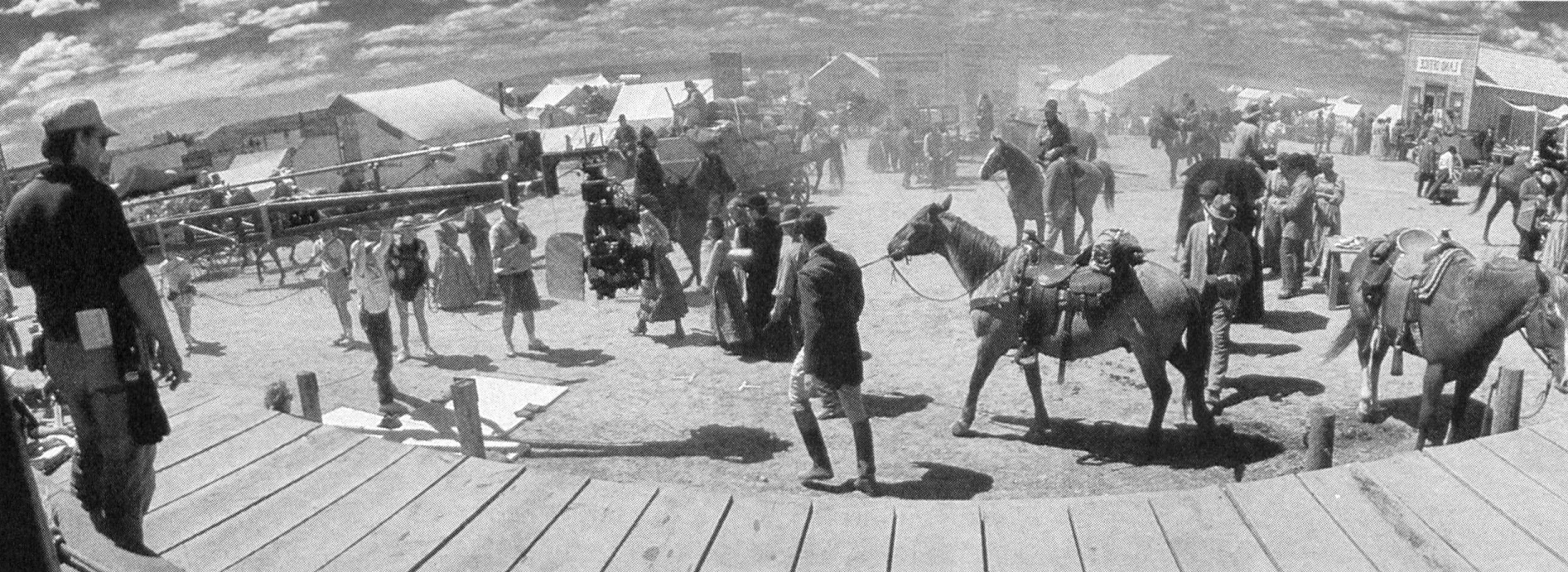

The most talked-about scene in the film, the land race, was photographed with nine cameras, including one on an 80'-high tower, a VistaVision camera on a helicopter, and two on Steadicams on a camera car, which allowed the operators to move smoothly with the flow of the action. A number of Eyemo 35mm cameras with anamorphic lenses were buried in the path of the horses and wagons with only the lenses were above ground to provide a ground-level view of the race.

Salomon used the Arriflex 765 camera to record images at the rate of 100 frames per second in this scene. The VistaVision images were blown up to 65mm format for blending with images from the other cameras.

The crowd of extras participating in this scene stretched over a quarter of a mile. Many of them were re-enactors — people who spend their summer vacations re-creating the 1893 land race in which Howard's ancestors participated. They came with their own horses, wagons and costumes. There were 200 wagons, 400 horses, and even people riding bikes. In all, in addition to the cast, there were 800 extras in the scene, which took only two minutes to shoot. There was a second take later in the day, but it didn't match the energy and spontaneity of the first.

Another scene moviegoers are sure to remember was shot in Montana during the golden hour, at the tail end of daylight, when the air itself is painted with a reddish-golden hue. The scene was impossible to shoot in one day and had to be pieced together from matched footage shot over a number of days. It opens with a fairly tight shot of Cruise. The camera, at the business end of a Python arm on a Titan crane, very gradually moves up and away, leaving the audience with a spectacular bird's eye view of the setting. Suddenly, the camera comes sweeping back to Cruise. In flight, the frame rate adjusts smoothly from 24 frames a second to six. As the camera comes in closer there's another seamless transition back to 24 frames a second. Finally, the camera returns to its original close-in perspective, with the dialogue continuing.

The Panavision 65mm camera can be programmed to synchronize shutter angle and frame rate. This allows the cinematographer to simultaneously change the frame rate and the shutter angle of the camera, making it possible to imperceptibly change exposure during the shot. It's as smooth as silk, and it happens so subtly that the audience is never aware that the images have been manipulated.

"Shooting a 65mm film is like comparing a compact laser disc to a vinyl record," he says. "You are getting a lot more fidelity out of the image. It's so pristine that you feel like you can step up to the screen and right into the picture. It's a different experience. But I don't think there is much that I would do differently if I were shooting the same film again."

Photography for Far and Away was completed on schedule in 103 days, stretching over four months. Salomon shares credit with his crew, including operator Greg Lunsgaard and assistants Ian Fox, Josh Bleibtreu, Steve Hiller, David Luckenback and Danny Teaze. He also has elaborate praise for Dash Morrison at Deluxe Labs, and for the various people at Panavision who participated behind the scenes in the making of this film.

Far and Away opened in at least 200 theaters in 70mm format and another 1,500 in 35mm format. Is it a nostalgic reminder of a magical time when movies were truly bigger than life? Or is it a new beginning? A lot will probably depend on how successful Far and Away is at the box office.

Grazer has an idea about that. "People ask me if it cost more to produce this film in 65mm. It didn't add much to our overall budget. We are fiscally responsible people. If you enhance the entertainment value of a film, you bring more people to the boxoffice, and add to the net revenues earned by the movie. Audiences are challenging us to make better films. We all have to dig deeper inside ourselves."

The effort represents much more than the revival of a once-elegant aspect of the filmic art. It's an effort to dig deeper inside the soul of the filmmaker, and give contemporary audiences a different type of experience.

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.