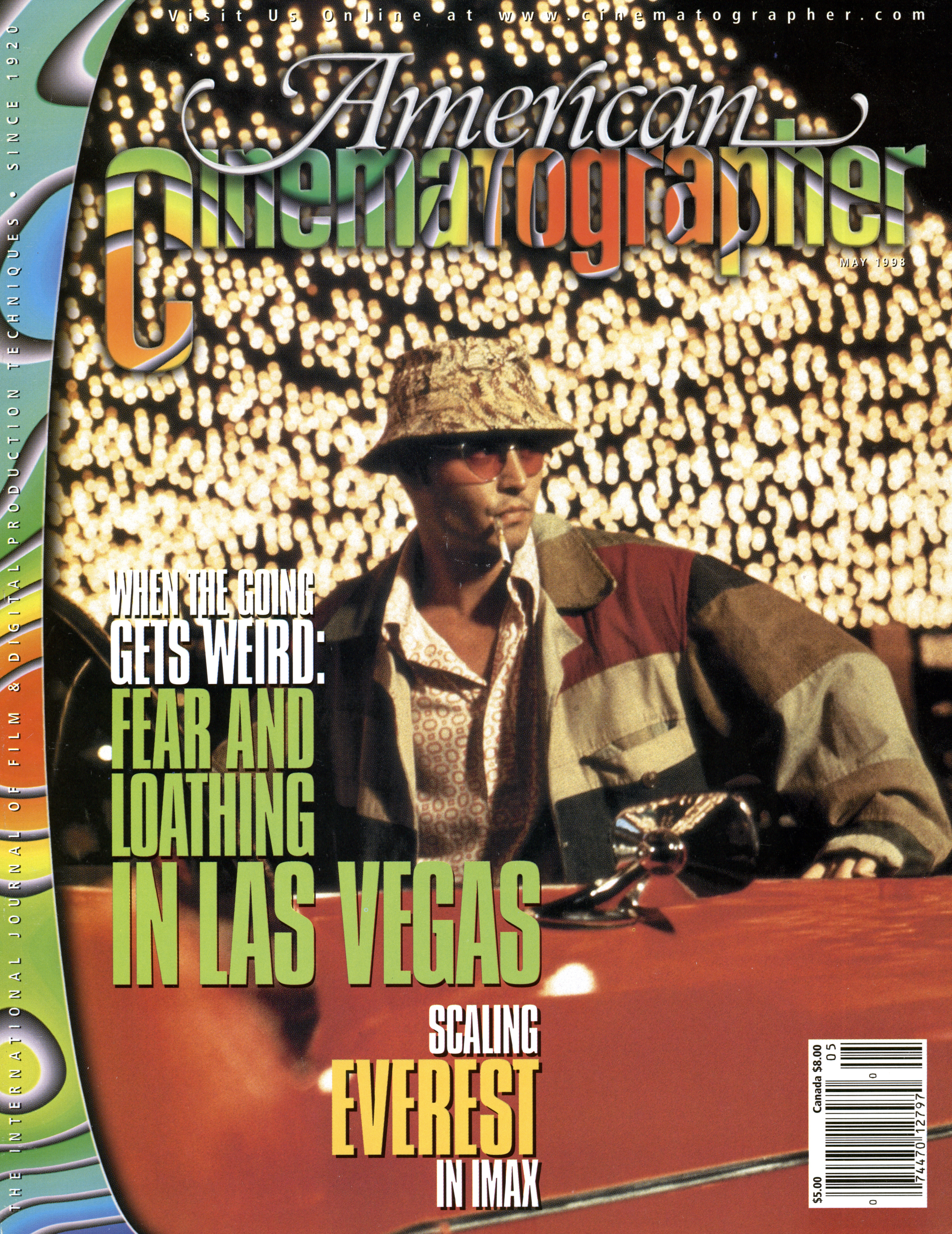

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: Gonzo Filmmaking

Cinematographer Nicola Pecorini heads to the American desert to help director Terry Gilliam unleash a long-awaited film version of Hunter S. Thompson’s counter-culture classic.

Unit photography by Peter Mountain, courtesy of Universal Pictures

Originally published in AC, May 1998

We were somewhere around Barstow on the edge of the desert when the drugs began to take hold. I remember saying something like “I feel a bit lightheaded; maybe you should drive... ” And suddenly there was a terrible roar all around us and the sky was full of what looked like huge bats, all swooping and screeching and diving around the car, which was going about a hundred miles an hour with the top down to Las Vegas. And a voice was screaming: “Holy Jesus! What are these goddamn animals?”

Since its initial publication in 1971, Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas has been the literary equivalent of a bottled genie begging for its cinematic release. The book’s subtitle proclaims it to be “A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream,” and Hunter Thompson’s drug-addled yarn delivers on that promise in spectacularly surreal fashion, whipping up a veritable tsunami of nightmare visions, paranoid rants and fire-and-brimstone diatribes that boil with apoplectic political rage. Within its pages, readers accompany wired but world-weary journalist Raoul Duke and his equally overamped Samoan attorney, Dr. Gonzo, on a non-stop chemical bender through Vegas, the metaphorical nerve center of a nation that has lost touch with the liberating ideals of the 1960s. Rife with elegiacal overtones, the duo's frenzied expedition becomes a demonic cross between Jack Kerouac’s On the Road and Dantes Inferno, rendered in a volcanic torrent of prose that erupts with the impact of a Hieronymus Bosch hellscape.

Although Fear has inspired one previous feature film (the straightforward and largely ignored 1980 adaptation Where the Buffalo Roam), Thompson’s cult following has persistently clamored for definitive screen treatment. With the uncorking of Terry Gilliam’s manic interpretation, the Freaks will finally have their day.

“On my reel, the screen starts out half-black. A friend of mine, director Tommy Schlamme, sits there speaking very highly of me, but he adds, ‘I have to warn you, though, that what you’re looking at right now is what Nicola Pecorini sees, because he has only one eye.’”

— Nicola Pecorini

Universal Pictures’ production of Fear and Loathing represents the culmination of a long and twisted industry saga. Over the past quarter century, the Hollywood rumor mill has rattled off a veritable roll-call of big-name directors (including Martin Scorsese and Oliver Stone) in connection with various aborted attempts to animate Thompson’s comically deranged opus. According to legend, the infamously mercurial — and mercenary — wordsmith helped to delay the undertaking by selling book rights to dozens of unsuspecting investors (some in perpetuity). After protracted bouts of legal wrangling, a go project was finally announced several years ago by producer Laila Nabulsi, with director Alex Cox (Repo Man) slated to take the helm. Cox eventually left the project, however, and was replaced by Gilliam, one of cinema’s most inventive visualists.

Thompson’s apocalyptic tale also lured in a stellar cast. The showy role of Raoul Duke (the writer’s fictional alter ego) was awarded to Johnny Depp, who subsequently spent four months tracking the author’s every move and mapping out his mannerisms. The part of Dr. Gonzo, Duke’s unruly and overweight attorney, was fleshed out (literally) by Benicio Del Toro, who gained close to 50 pounds to approximate the character’s slovenly girth. The picture’s impressive array of supporting players includes Tobey Maguire, Christina Ricci, Ellen Barkin, Gary Busey, Cameron Diaz, Mark Harmon, Katherine Helmond and Harry Dean Stanton.

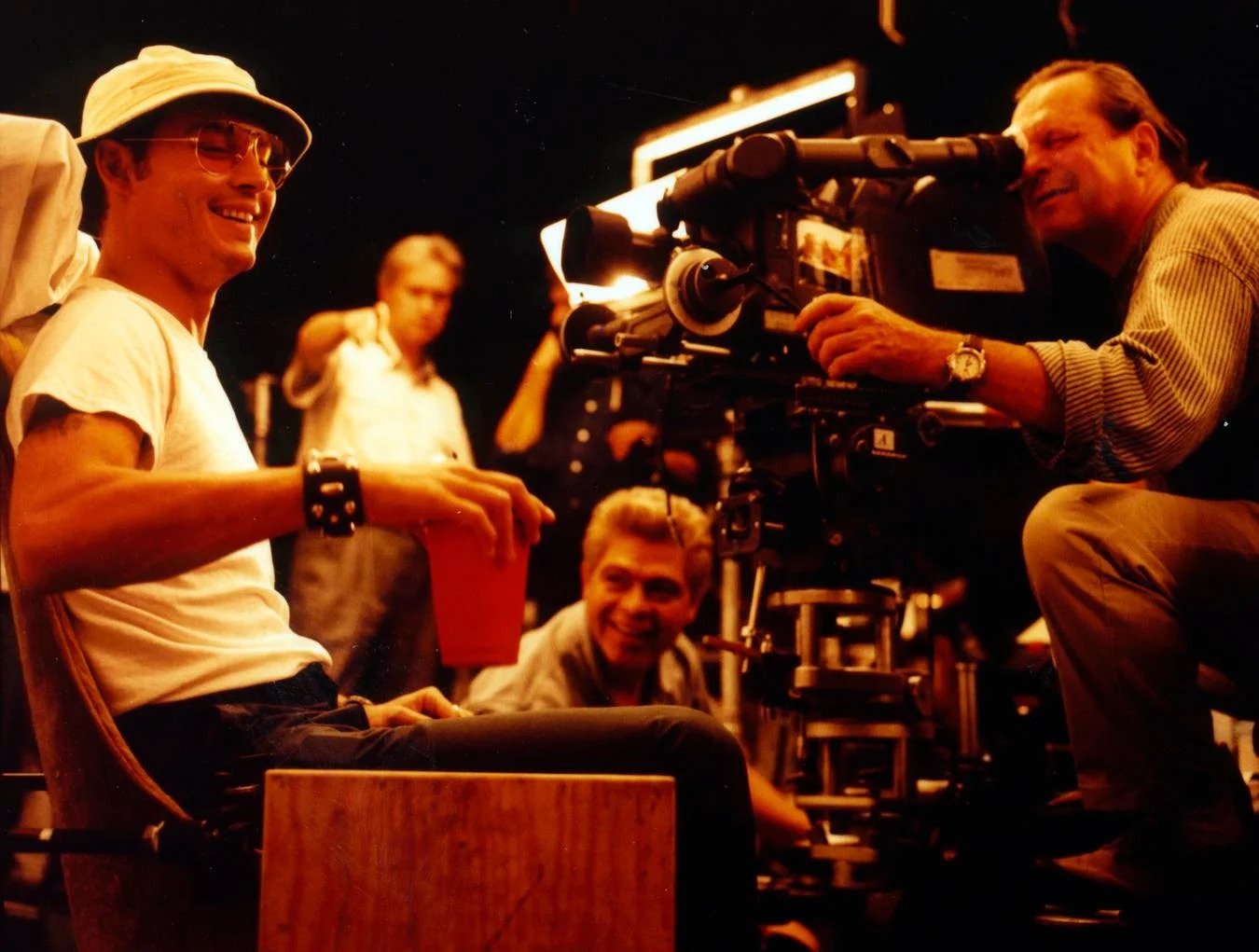

Given this assemblage of talent and the story’s strong visual potential, most cinematographers would have given their eyeteeth to land such a plum assignment. As it turned out, director of photography Nicola Pecorini won the job by amiably acknowledging that he had already sacrificed an eye. Following up on a tip from Depp (whom he had met while shooting footage for the actor’s directorial debut, The Brave), Pecorini sent Gilliam a highly unusual audition reel which made light of the fact that the cameraman has sight in just one of his sockets. “I’ve seen how people look at demo tapes,” says Pecorini, who lost his left eye to retinal cancer when he was just 16 months old. “Usually someone will put the tape in, look at it for 30 seconds, and then start taking phone calls or typing on the computer. On my reel, the screen starts out half-black. A friend of mine, director Tommy Schlamme, sits there speaking very highly of me, but he adds, ‘I have to warn you, though, that what you’re looking at right now is what Nicola Pecorini sees, because he has only one eye.’ Then he stands up and takes a piece of black tape off the lens to show the difference. If you’re watching the reel, you immediately say to yourself, ‘Who is the jerk who sent me this tape?!’ Now that I know Terry, I can understand why he liked it, because the first thing he wants to know about someone new is, ‘Can he laugh?”’

Indeed, Pecorini’s ability to spoof himself convinced Gilliam that he had found his man, despite the fact that the cameraman had previously served as lead cinematographer on only one feature film: the Sundance standout Rhinoceros Hunting in Budapest (see festival coverage in AC April ’97).

In reality, however, Pecorini’s photographic pedigree was far more extensive than that. His grandfather, Fedele Toscani, had been a pioneering photojournalist in Italy during the 1920s, and young Nicola grew up in darkrooms. During his teens, he found work as a fashion photographer but quickly grew bored with the repetitious shoots. His father, a journalist, introduced him to a friend who needed a cameraman to shoot 16mm news footage in Geneva, Switzerland, and Pecorini spent the next three years filming everything “from hockey games to short pieces about the lives of spiders.”

The budding cameraman found these varied experiences to be invaluable but soon sought bigger challenges. During a vacation to the U.S. in 1981, he picked up a copy of American Cinematographer, in which he spotted an ad for one of the first West Coast Steadicam workshops. Upon attending the classes, he instantly fell in love with the revolutionary new filmmaking rig. “All of a sudden I had one tool that would enrich my vocabulary in making motion pictures,” he says. “The great thing about the Steadicam is that you don’t need mediation with anyone else. The dolly is a great tool, and so is the crane, but you always have to rely on more than one man. With the Steadicam, you become one with the camera.”

Pecorini soon purchased his own Steadicam, and over the next 16 years, he found an abundance of work in Europe with many renowned cameramen, including ASC members Giuseppe Rotunno and Vittorio Storaro, as well as Tonino Delli Colli. He eventually became a trusted lieutenant to Storaro, who promoted him to B camera operator and second-unit director of photography. "Little Buddha [AC May ’94] was a bit of a turning point for me,” says Pecorini. “The logistics of the shoot were very complicated, so Vittorio delegated quite a bit of work to the second unit. I learned that I could take responsibility, and that’s when I decided to become a cinematographer.”

His first job as a fully-fledged director of photography was a collaboration with Schlamme on the first season of the HBO series Tracy Takes On... in 1995. Pecorini then shot the low-budget Rhinoceros Hunting in Budapest for Michael Haussman. He says that he accepted the assignment for two reasons: “First, I had worked with Michael before as an operator, and we’d gotten along very well; second, I was the only one who would take that little money! It was a small movie, with a budget of about $1.4 million, but the script was good and I thought it had a lot of potential. Creatively, it was a very rewarding experience.”

Pecorini admits that he is still astounded to have landed the Fear and Loathing gig, but he reports that Gilliam’s collaborative nature and team ethic made the transition to a major feature quite rewarding. “Terry is able to put his ego aside on the set, and that makes him a joy to work with,” the cinematographer attests. “Let’s say you have a complicated scene with 25 candles that need to be lit. If things are moving slowly, he may start clapping his hands and saying to the prop man, ‘C’mon, c’mon, what are you doing?’ And the prop guy might get mad and say, ‘I’m lighting the candles for your movie!’

But Terry will reply, ‘Not my movie, our movie.’ That’s a big thing, because it’s very rare to find people like that. When some directors walk onto the set, they won’t even say ‘Good morning.’ But Terry constantly has his sensors attuned to the crew’s mood and state of mind.”

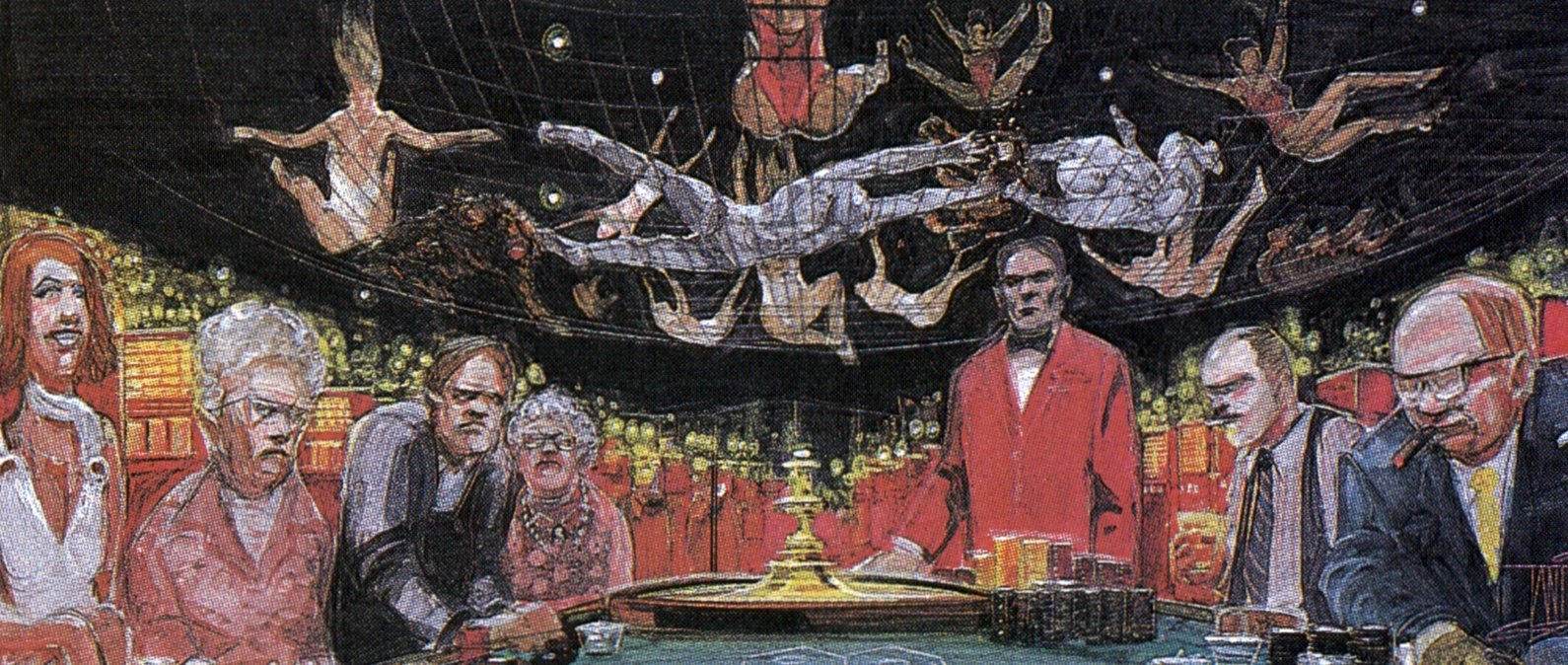

During the duo’s preproduction discussions for Fear and Loathing, Pecorini also discovered that Gilliam had no qualms about doling out creative challenges to his new cinematographer. “He came to me with this book of paintings by Robert Yarber and said, ‘I want the movie to look like this.’ Our production designer, Alex McDowell [The Lawnmower Man, The Crow], introduced Terry to this guy’s work, which is very hallucinatory: the paintings use all kinds of neon colors, and the light sources don’t necessarily make sense.

“I had about two days of panic after Terry told me what he wanted,” Pecorini confesses. “But then I said, ‘If he wants red skies, I’ll give him red skies.’ The way I approached it technically was to use colored gels in front of my lights. We did a lot of tests, mainly with Roscolux and CalColor gels.” Key selections included Roscolux fire (#19), gold rush (20), pistachio (92), chocolate (99), walnut (156), follies pink (344) and Italian blue (370), as well as CalColor red (4660) and pink (4890).

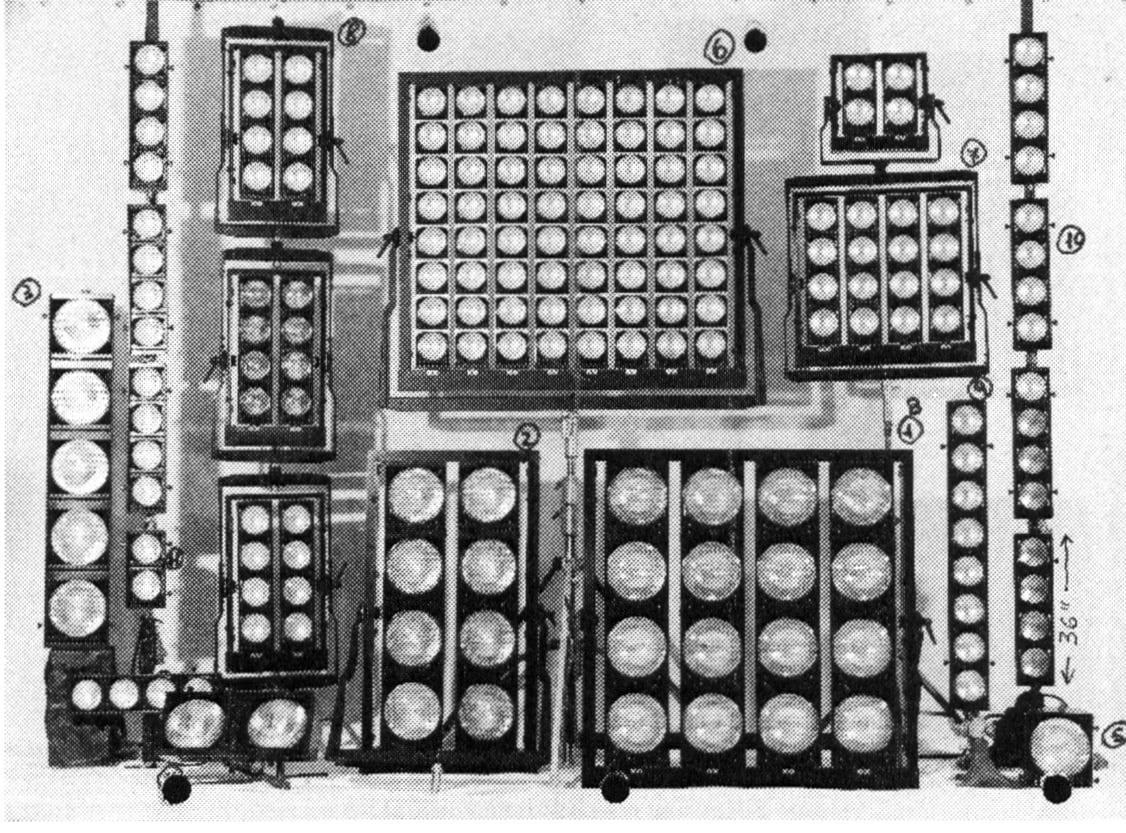

Pecorini mounted his multicolored array of gels in front of a special series of Italian-made lighting units that had been pioneered by Vittorio Storaro. “Some years ago, Vittorio saw these landing lights for airplanes, and he began thinking about using multi-point sources in the same types of frames,” Pecorini explains. “The guy who makes them, Pippo Cafolla, is Vittorio’s longtime gaffer, and his company in Rome is called Iride. Pippo has two sons, Fabio and Daniele, who also work at the company. Fabio has been Vittorio’s console operator for about 12 years; Daniele works more as a spark [electrician], but he gaffed for me on Rhinoceros Hunting in Budapest. Pippo started out by making these units called SuperJumbos, which have 24 [600W or 1,000W] lights in them, and Jumbos, which have 16 lights. There are also Mini-Jumbos, with eight lights, and Tornados, which have smaller fixtures [650W Par 36s]. These various units have a lot of kick, and if you place them at the right distance, you will get only one shadow. The lights work on a dimmer system, though, so you have to keep that in mind when you’re designing your lighting plan.”

“The lights are great, but you have to be careful with them, because it’s easy to blow them out when you turn them on.”

For Fear and Loathing, Pecorini ordered a 200-kilowatt package of the Italian units. “The lights are great, but you have to be careful with them, because it’s easy to blow them out when you turn them on,” he cautions. “You have to bring them up quite slowly with the dimmer console. At the beginning of the show, we lost a few lights! Later on, in the desert, we also had some problems with the sand in the dimmers, so Daniele came to the States to help us out.”

Pecorini used the Iride fixtures for majority of his lighting needs, but he supplemented them with a selection of Kino Flos, Par cans, babies and peppers. “I don’t like the texture of HMI lights,” he states. “They don’t look real to me, especially if you’re trying to simulate the sun. I much prefer putting up a battery of six or seven Jumbos 100 feet away with a ½ blue gel in front of them. On this show, I got my special lighting package from Rome and the rest from the [Burbank, California-based] Hollywood Rental Company, which had just come out of more or less the same experience, on a much bigger scale, with Bulworth [Warren Beatty’s upcoming film, photographed by Storaro, which will be covered in the June issue of AC].”

Given the desert vistas of Fear and Loathing, Gilliam and Pecorini opted to shoot the picture in widescreen Super 35. The cameraman was familiar with the format, having worked as an operator for director of photography Ronnie Taylor, BSC on Italian horrormeister Dario Argento’s 1988 fright-fest Terror at the Opera. “We chose Super 35 over straight anamorphic for several reasons. First of all, with anamorphic, you don’t have a wide enough choice of lenses. And while I love the format, I don’t like the opticality of it. It’s an optical aberration to start with, and it’s an optical aberration to correct it once you project it. The ideal anamorphic would be to have the same morphing lens that you shoot with to project with. Of course, you can’t have the same lens on every projector in the world!

“The other thing is that while there is a 20mm anamorphic lens, it weighs a ton, and to work decently you have to shoot at T5.6 at least. You can forget about having strong backlight with anamorphic. I’ve worked on a lot of anamorphic films, and have endured some terrible experiences with it. You always die during the dailies, and you invariably have to reshoot something purely due to the optical instability of the lenses. I didn’t want to go through that sort of thing on this show, and we didn’t have the money to do it anyway.

“I’d never been in charge of a film shot in Super 35, but I knew most of the problems that came along with it,” Pecorini adds. “Most of those weren’t a factor, because I don’t use zoom lenses, so I couldn’t care less about the vignetting. I don’t like zooms too much; a good focus puller can change the lens in literally 20 seconds, so why bother with a zoom?”

Pecorini did bend his no-zoom rule to achieve one unusual shot which creeps into one of Duke’s eyeballs, where a hallucinatory horde of bats can be seen flapping about. “We needed to stay inside Johnny Depp’s pupil; I tried doing that shot with a macro lens, but it was too difficult. You have to choose the pupil or the iris, and it becomes very tricky; you’re dealing with 1/100 of an inch, and there’s a moment when things become fuzzy. In order to avoid that moment, I needed to use so much light that I was working at a stop of T11 or 16; Johnny was sweating and we couldn’t do it anymore. In the end, we used a 10:1 zoom with diopters. The bats were added later by [visual effects supervisor] Kent Houston at Peerless Films, Terry’s company in London.”

For the balance of the film, however, Pecorini shot with Zeiss Standard Speed prime lenses. “I love the Zeiss primes: you can have unbelievably violent kicks from backlight, but those lenses just don’t care. That’s a great quality, especially if you work at [a stop of] T2.6 or 2.7, like I do. I drive my focus pullers crazy with those kinds of stops.”

“We were sometimes literally shooting with a 12mm lens three inches away from Johnny Depp’s nose.”

In terms of specific lens choices, Pecorini indulged Gilliam’s preference for wide angles throughout the shoot. “I’d say that we shot about 95 percent of the film with 10mm, 12mm or 14mm lenses; that was our primary range! Sometimes I would check out a shot and say, ‘This is 16mm,’ and Terry would look at me and joke, ‘Are you nuts? That’s a telephoto!’ We were sometimes literally shooting with a 12mm lens three inches away from Johnny Depp’s nose.”

The cinematographer’s main camera of choice was the Arriflex 535, which allowed him to do a few speed changes during the film’s driving scenes. “The speed changes were fairly subtle,” he notes. “We sometimes went from 24 to 20 fps to make the car turn faster or take off faster.” Elsewhere on the show, Pecorini employed an Arri BL-4S and an Arri 35-III.

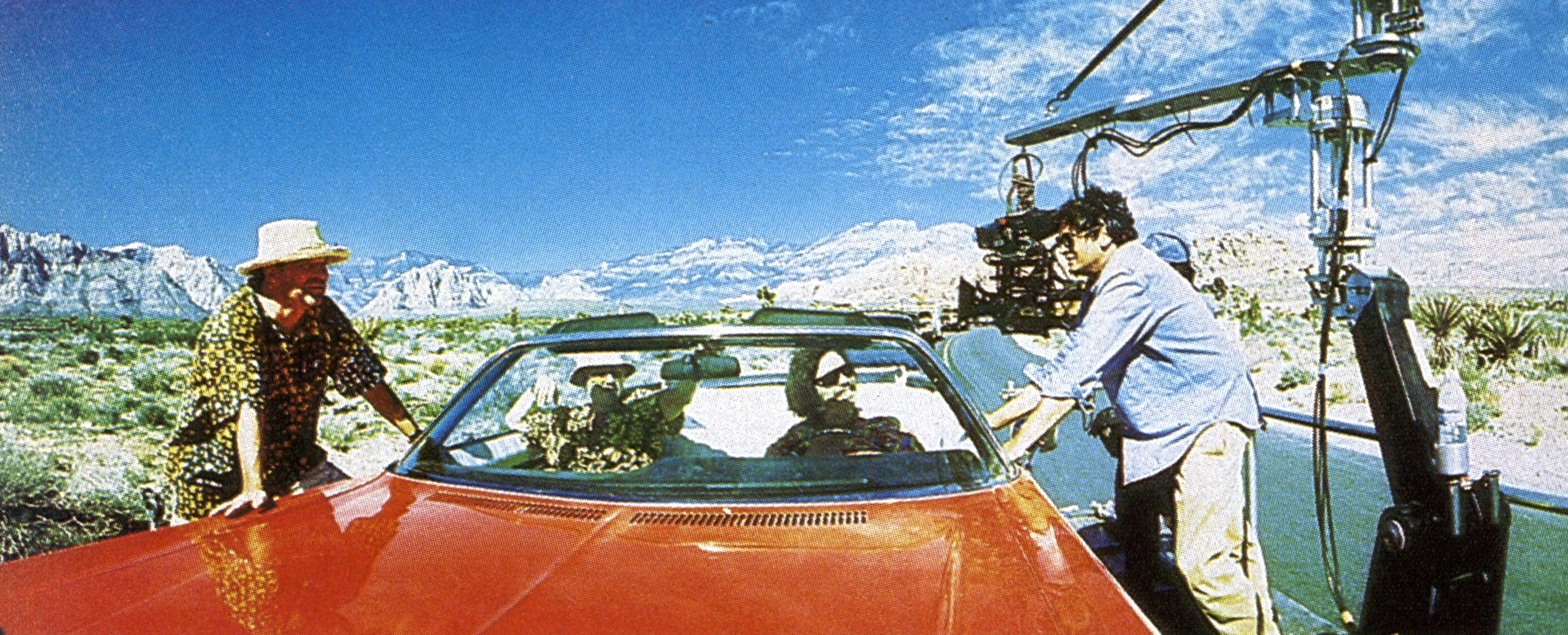

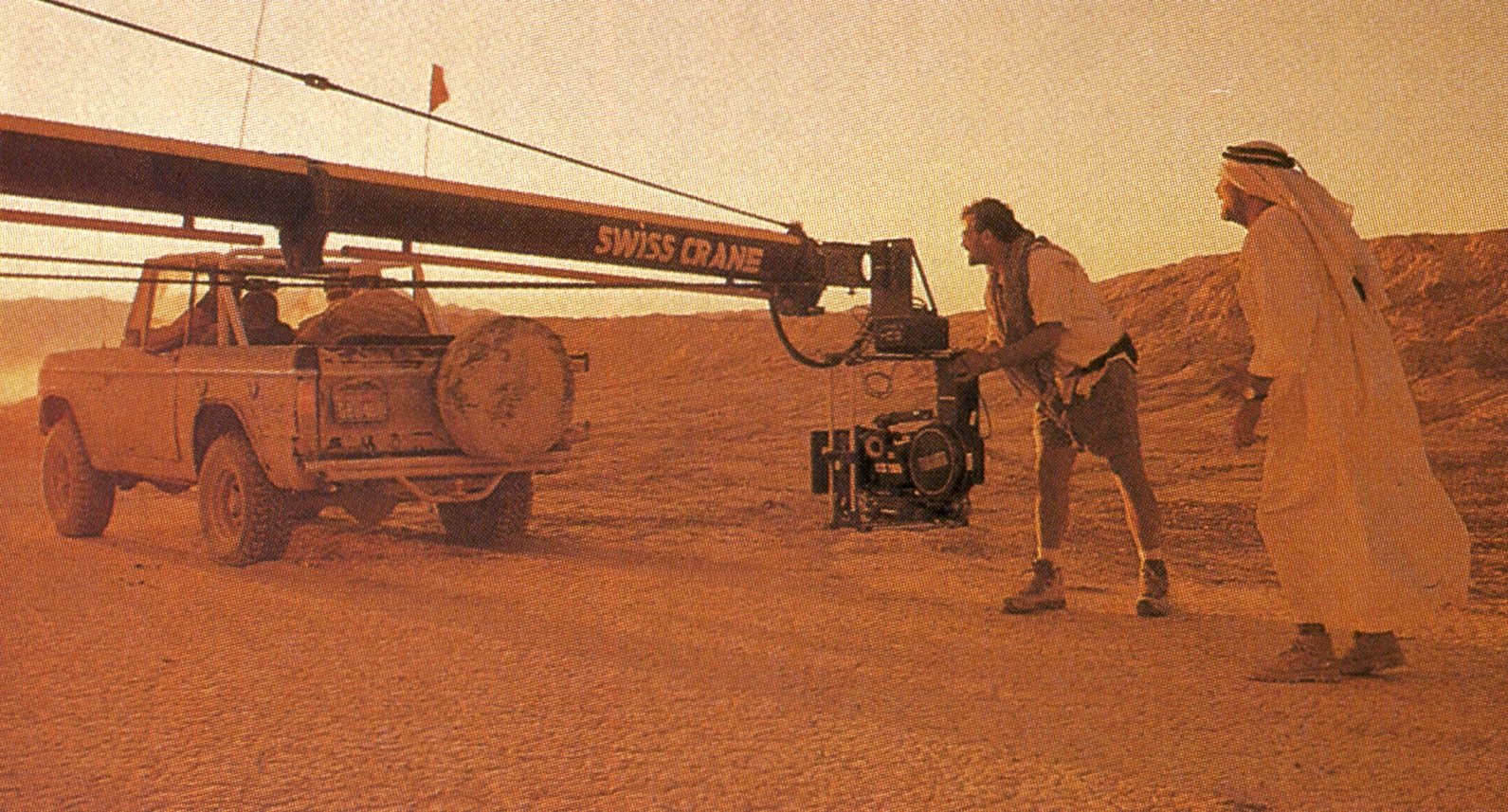

Pecorini shot all of the picture’s exteriors on Eastman Kodak’s 250D Vision 5246 stock, which he found to be well-suited to the early scenes of Duke and Gonzo’s raucous road trip to Vegas in their “Red Shark” convertible. “Vittorio had a batch of 5246 that he was testing on Bulworth, and I really liked it,” says Pecorini, who did some operating on the picture for his old friend. “It has an amazing latitude, especially for overexposure. In the desert, we wanted the images to have a certain undefined quality, without a real horizon anywhere; we wanted it to seem as if you could never really get to the end of the desert. There’s a certain kind of unreality outside the characters’ car because everything that matters to them is within the Red Shark. For that reason, I always used an 85 filter during those scenes, even though we were shooting in daylight. Because of the overexposure, the warmth is readable only in the undertones; the background might be really hot and burned-out, but it doesn’t seem fake. Certain colors would change, though — the greens disappeared completely.

One of the problems we had was that we shot in the desert for three weeks at the beginning of the shoot, but then had to go back during the last week of production, when the desert had a completely different look!” he notes. “It had rained in the interim, so everything was lush and green. The most time-consuming thing we faced in the timing was ‘evening out’ all of our exteriors.”

During that second tour of the desert, Pecorini also faced another, more “hair-raising” dilemma. As fans of Fear and Loathing will recall, Duke and Dr. Gonzo extend some roadside hospitality by picking up a hapless hitchhiker, only to end up terrorizing the poor fool with their drug-crazed antics. “The hitchhiker was played by Tobey Maguire, but we had to shoot his scenes at both the beginning and the end of the schedule,” the cinematographer reveals. “His character is supposed to be almost bald with a few strands of long hair, but Tobey got another job during the ensuing weeks, and grew his hair back. The morning he showed up for his final scenes, we were like, ‘Oh God, how are we going to do this?’ He had to wear a bald headpiece, but you could still see that there was hair underneath. Fortunately, the fact that we had overexposed the earlier scenes helped us a lot, because I could just burn him out a bit. Terry had this idea that the hitchhiker was like the Angel of Life and Death, so he was always a bit brighter than the other two characters. We just lit him a bit more or took light away from the others; since Johnny and Benicio were in the front seat and Tobey was in the back, we could just put a piece of Duvateen on the windshield and it was done.”

“One of the most common mistakes I’ve seen over the years is when people try to fight the sun. That’s why I don’t like HMIs; using them to try to create the sun is a bit like playing God, and I find that to be a bit pretentious.”

The cinematographer reveals that he took an extremely naturalistic approach to the road-trip footage in order to avoid the “equipment overload” that plagues most productions faced with insert-car work. “I never use lights on insert cars,” he maintains. “One of the most common mistakes I’ve seen over the years is when people try to fight the sun. That’s why I don’t like HMIs; using them to try to create the sun is a bit like playing God, and I find that to be a bit pretentious. Every time I’ve seen an insert car lit, it’s never looked real to me. For example, if you’re driving and a truck passes by, the light [outside the car] changes, but your light doesn’t! And if you drive too close to a sign on the road, the bounce off the sign will read inside the car. I try to use the sun alone; if there’s no sun, I use the bounce off the sky. In my opinion, the light source in those situations has to respect a dependence on the real elements, so I always use just mirrors or bounce cards. I might use a piece of headboard cut into a certain shape just out of frame next to the driver’s door, or position four little 1' by 1' mirrors on the car to produce little kicks and fill. I like to use the imperfections that are common to real light, such as certain reflections you get from the chrome of the car or the rearview mirror.”

Pecorini notes that all of the trailer-mounted car scenes were shot either handheld or with a bungee cam [a Pee Wee dolly with an offset head]. More complicated master shots of the Red Shark in motion were achieved with a Shotmaker arm equipped with a remote head.

For scenes that required period Vegas landscapes behind the characters as they drove, the filmmakers found a creative and appropriately retro solution. “We scouted a lot in Vegas, but there’s not much architecture left from the 1970s,” Pecorini notes. “Another restriction was that with our budget [approximately $18.5 million] we couldn’t afford many visual effects. We decided to do a lot of things in camera, so one of our strategies with the car footage was to use rear-projection.”

Fortunately, the film’s Los Angeles base was Warner-Hollywood Studios, which turned out to be a treasure trove of rear-screen resources. “Spelling Television has an archive there with an unbelievable amount of stuff from the old TV show Vegas — including rear-projection plates that had been shot with three cameras from various angles. You could build an entire scene by putting together these different viewpoints! We spent about two weeks selecting various plates from those archives — sunset and dusk scenes, as well as shots of Fremont Street the way it used to be.” The vintage plate shots proved to be an inspired choice, heightening the story’s already otherworldly tone an extra notch.

Some of the film’s more expansive Vegas vistas were created with modern methods by the visual effects company Illusion Arts. A good example is a sequence in which Duke and Gonzo arrive at the registration tent for the “Fabulous Mint 400,” an offroad race which Duke has been assigned to cover for a major sports magazine. The shot begins with a shot of the period Vegas skyline, and then pans down to the bustle of activity on the street below. Notes Pecorini, “We shot the lower part of the scene, and Illusion Arts added the rest digitally.”

Later in the film, Gilliam and company blended traditional and computerized effects techniques to achieve the tale’s most outrageous tableau: a nautically-themed cocktail bar populated by genuinely reptilian “lounge lizards.” The vision of these peculiar patrons is, of course, produced by the abundance of recreational chemicals that Duke has ingested; the lizards themselves were animatronic replicas built by creature creator Rob Bottin (The Thing, Deep Rising). “That scene was quite difficult because we didn’t have enough of the animatronic lizards,” says Pecorini. “We were supposed to get about 25 of them, but we wound up with just seven or eight. As a result, we had to use motion-control techniques to make it look as if we had a whole room full of them. That sequence took two full days to film. We had to do all of these different passes with different costumes on the various lizards to get it right. To make things worse, the set consisted almost entirely of mirrored surfaces, which was a nightmare for me. Hiding the camera, therefore, became a question of using the right shooting angle.

“I didn’t have that much room to move lights around, so I didn’t use the Jumbos to light that sequence; we used either practical or little sources aimed at the things we wanted to see. I used these flashlights called Stream Lights — they’re like big Maglites, but they’re rechargeable. They would last a good hour without recharging. I adapted pepper snoots for them so we could contain them and gel them. That way, we could hide everything without running any cable. We shot it all on Kodak’s 5293 stock, because the footage needed to be manipulated so much that we wanted the most perfect grain we could get.”

Pecorini’s love of the EXR 5293 led him to use it on all of the film’s interiors. “I just love that film stock: the blacks are amazing. I had originally thought about using the ENR process on this film, but I ultimately decided that it wasn’t necessary. Before I shot the movie, I called Vittorio Storaro down in Argentina, where he was shooting Flamenco for Carlos Saura. I asked him very honestly whether he thought ENR was really needed in this day and age; I felt that with the latest stocks, it was possible to achieve those kinds of blacks and densities without such a process. He said, ‘I agree with you, and I don’t think I’m going to be using ENR anymore myself.’

“The latitude [of the 93] really helped us on this show when we were filming scenes in the Mint Hotel suite, because those sequences were extremely dark. I was using minimal lighting and heavy-duty colored gels on the lights — three full Italian blues. A single Italian blue takes away two stops, so we were taking away six; the light that was coming through was nothing. I was exposing at T2.5, and it would read as an error on my meter! The highlights were almost one stop underexposed, so the lowlights were about three stops underexposed. But we still had the actors’ eyes”

“Kodak’s Vision 5279 is also an amazing film stock, but the latitude was too wide [for our purposes],” he opines. “We would have had all kinds of highlights popping out. Sometimes I had to use 79, such as when we shot in real casinos; the limitations imposed upon us required it. We couldn’t use as many lights as we wanted, because the management in those places didn’t want us to bother the gamblers. We had very little time to set up.”

Logistical considerations also came into play during filming of the Mint 400 race sequences, which were staged 30 miles south of Vegas at the Jean Dry Lake Bed. In accordance with Hunter Thompson’s literary depiction of the event, the race eventually devolves into a massive cloud of sand and dust that all but obscures the participants, who barrel over the sun-baked terrain on motorcycles and in dune buggies.

To whip up a dust storm of truly epic proportions, the crew used a jet engine mounted on a truck to blow sack after sack of Fuller’s Earth into the atmosphere. “That scene was just agony to shoot,” Pecorini recalls with a groan. “It was blazing hot, and we had to seal all of the equipment in plastic wrap to protect it. We had this group of about 20 bikers with us for three days, and we were constantly using two or three cameras. We had these amazing moments of total dust, where you would just see a shadow of something passing by. To keep the sand out of the lens, we used a rain deflector that operated with a little tank of air; there were a few hoses that you could mount on the edges of the matte box, and somehow they managed to keep most of the dust from coming in.

“At the height of the chaos, when Duke is aboard a jeep with a photographer named Lacerda, we had to shoot night-for-day because we ran out of time,” he reveals. “It actually wasn’t that difficult, because Fuller’s Earth is the most amazing diffusion that you can have; I just lit up the dust with my Jumbo lights. There were some dailies of that footage that were really funny; sometimes the takes would go on a bit too long, and the special effects guys would cut off the Fuller’s Earth, causing the scene to suddenly go from full sun to complete blackness!”

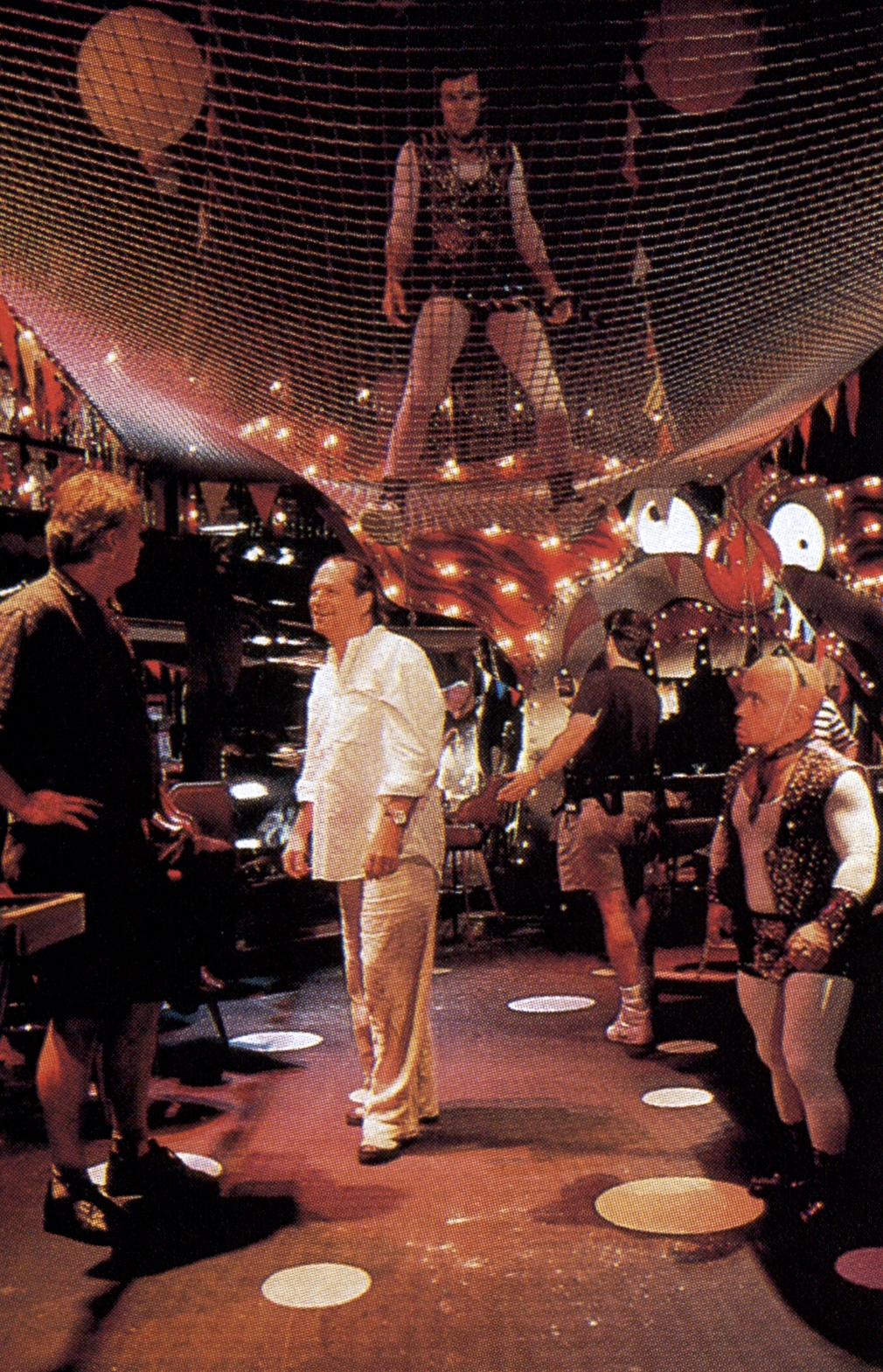

The filmmakers faced an entirely different challenge for stagebound scenes involving Duke and Gonzo’s visit to the Bazooko Circus, a phantasmagorical casino with a big-top theme. In the book, of course, these debauched scenes take place at the Circus Circus, a real-life gambling emporium; not surprisingly, the management of that establishment was less than eager to cooperate with the production, forcing Gilliam’s team to create their own carnival of excess.

Exterior shots of the Bazooko’s cartoonish entrance — a giant clown’s head with a gaping grin — were filmed at the front doors of the Stardust hotel/casino in Las Vegas, while the fictional fantasyland’s elaborate interior was constructed within a Warner-Hollywood soundstage. Production designer Alex McDowell was given free rein to produce a thoroughly over-the-top setting with two separate levels. The ground level consisted of a gambling floor, above which hung a safety net used by a team of aerial acrobats. McDowell’s team also constructed a steep ramp leading up to a separate midway area featuring an array of outlandish carnival games and attractions. “To light the gambling floor, I mainly used rock ’n’ roll truss rigs equipped with Par cans,” Pecorini details. “I also had a few of my Jumbos working. I asked the best boy grip, Vidal Cohen, to mount them on the ends of these big metronome-like devices so that the light would move back and forth, bounce off various mirrors and travel all over the place. Each light had a different-colored gel on it as well, so it was really crazy.

“On the midway level, I put up some Par cans, but that area was lit mainly with practical within each of the booths. I also used a lot of gelled Kino Flos and some China balls. The midway attractions were pre-existing games that we adapted for our own purposes, so there were already some limitations in terms of how we could light those. But I think limitations can be great sometimes because they make your decisions easier!”

Pecorini’s Steadicam expertise came in handy during the filming of the Bazooko scenes. “We didn’t do that much Steadicam work on the rest of the film, but almost everything at the Bazooko Circus was done with Steadicam, because we really wanted to lend those scenes a feeling of craziness. We also didn’t want the extras and all of the surroundings to be limited by the technicalities of the shoot; we never wanted the first A.D., Phil Patterson, and his seconds to have to tell the actors, ‘Don’t step on the tracks.’ The great advantage of using Steadicam is that you can adapt to the shot or save the shot as things happen around you. Over the years, I’ve gotten very good at shoving people out of the way!”

Of course, no big-screen rendition of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas would be complete without the requisite interludes of copious chemical indulgence. In order to effectively convey the various altered states experienced by Duke and Gonzo, the filmmakers prepared a list of “phases” which detailed the cinematic qualities of each drug consumed by its lead characters. These substances include — but are hardly restricted to — ether (“loose depth of field; everything becomes non-defined”), adrenochrome (“everything gets narrow and claustrophobic, move closer with lens”), mescaline (“colors melt into each other, flares with no sources, play with color temperatures”), amyl nitrate (“perception of light gets very uneven, light levels increase and decrease during the shots”), and of course LSD (“expanded consciousness, everything extremely wide, hallucinations via morphs, shapes, colors and sound”).

“We used a lot of moving light during the acid sequences. The lights were always going up and down and flashing and crashing. We also made liberal use of our colored gels.”

The most visual of these drugs, acid, was given some extra visceral impact with the help of some low-tech ingenuity. “We were originally going to use Clairmont Camera’s ‘squishy lens’ for those sequences,” Pecorini explains. “They took two lenses made of some unbreakable material and sealed them at a certain distance from each other, filling the gap with optical liquid and adding three motors that could compress and distort the lens. Unfortunately, that lens wasn’t available to us, so we came up with an alternative. We got some pieces of this material called Lexan, which is like Plexiglas, and the grips cut it into 6" by 6" squares and put it into a 6" by 6" filter frame attached to a swiveling matte box. We then used a gas-powered soldering gun to make dents in the Lexan. The result was an optical flat with a different texture in the middle. When we moved that [over the lens], certain areas of the image — a character’s mouth, for example — would suddenly go soft; everything else would look normal except for that one spot. The idea came to me one day when I was looking at a piece of ordinary kitchen plastic wrap. If you make it really nice and tight it’s like an optical flat, but if you rub your finger on it, it smudges. You can’t control the effect so well with plastic wrap, but you can be very precise with Lexon.

“We used a lot of moving light during the acid sequences,” he adds. “The lights were always going up and down and flashing and crashing. We also made liberal use of our colored gels. For example, the same window might have five different colors hitting it, but never at the same time; they would be fading in and out on the dimmer. Eric Erickson, my dimmer operator, would be playing his machine as if it were an organ! Sometimes we would both be working the dimmer simultaneously. One day we were all watching dailies of those scenes and Terry said, ‘Is there a color we didn’t use?”’

Despite the show’s hell-bent 56-day schedule, frugal budget, and difficult shooting conditions, Pecorini describes his Fear and Loathing experience as “a very important turning point” in his creative career. He emphasizes the fact that he owes a debt of gratitude to both Gilliam and his core crew members (camera operator Frank Perl, first camera assistant Steve Itano, B-camera first assistant Lucas Bielan, second assistant Hilton Goring, gaffer Chris Lyons, dimmer operator Eric Erickson, key grip Peter Chrimes and loader Forrest Thurman), and underscores the importance of staying open to new ideas during a shoot. “In my opinion, if the movie you get in the end is exactly what you thought it would be at the beginning, you didn’t do a good job. A movie should surprise you and go much further than you’ve planned. The unpredictable can always play a wonderful part in a production; many times it will turn out better than you initially thought possible!”

If you enjoy archival and retrospective articles on classic and influential films, you'll find more AC historical coverage here.