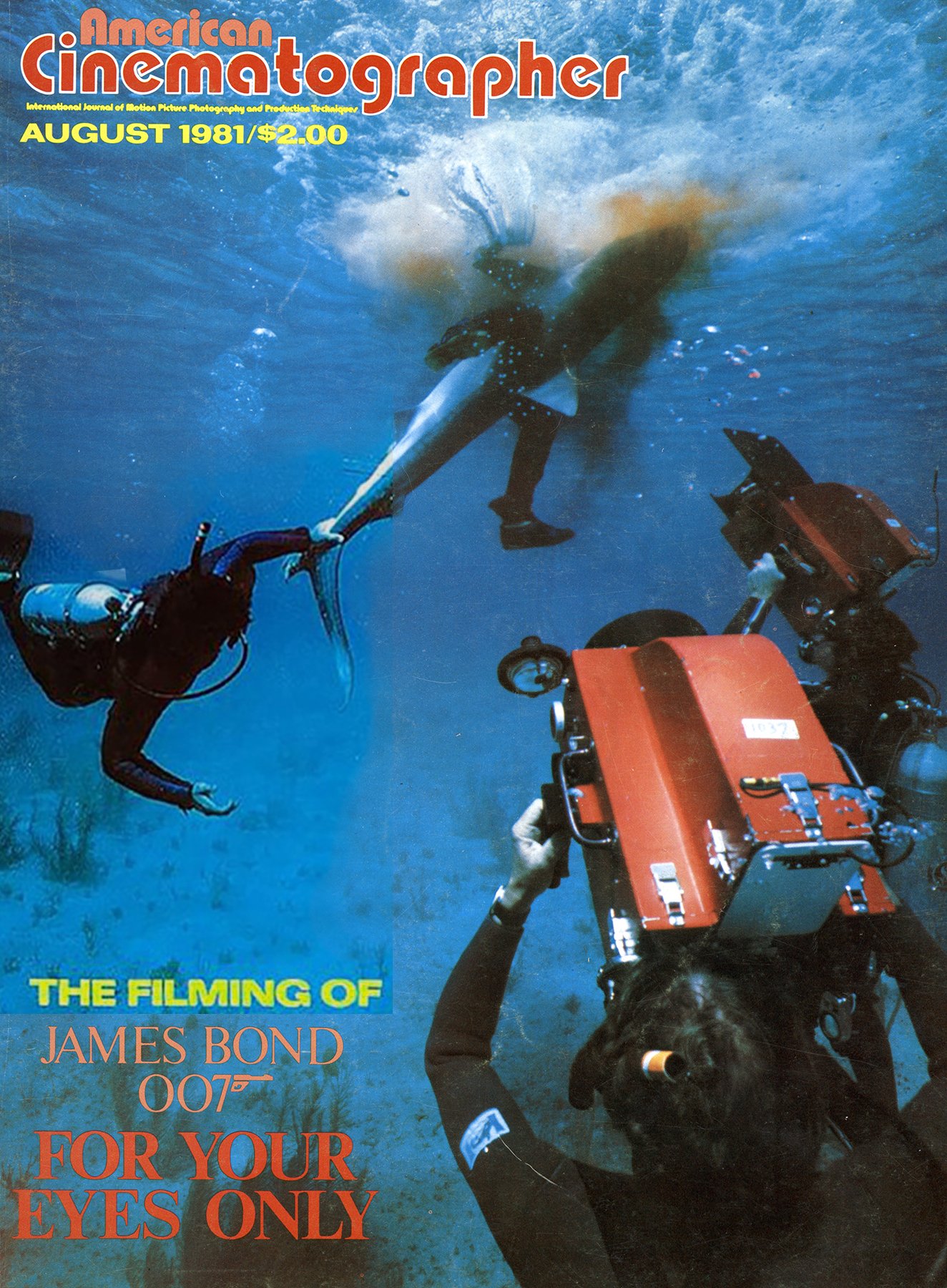

Photographing For Your Eyes Only

For the August 1981 issue of AC, some of those responsible for the filming and production — including Alan Hume, John Glen, Willy Bogner, Paul Wilson and Jimmy Devis — shared their experiences.

By Alan Hume, BSC

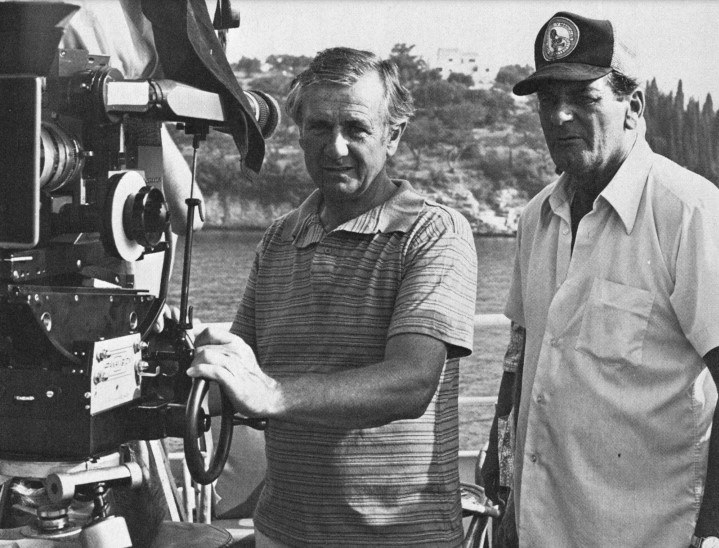

To be given the job of photographing a James Bond picture must be some sort of achievement in itself. That is certainly how I felt when director John Glen and producer Albert “Cubby” Broccoli announced that I was to photograph For Your Eyes Only.

John had already done a lot of thinking about his approach to the logistics of shooting two hours-plus of a fast-moving action film. The final slate number of the main unit alone was 11094, but eventually, the picture was shot by six units, as follows:

- Main Unit

- 2nd Unit - Director/Cameraman Arthur Wooster

- Helicopter Sequence Unit - Director/ Cameraman Jim Devis

- Underwater Unit (Bahamas) - Director/Cameraman Al Giddings

- Special Effects Unit - Director Derek Meddings/Cameraman Paul Wilson.

- Ski-chase Unit - Director/Cameraman Willie Bognor

The schedule was eventually set for 20 weeks of shooting, which broke down to: six weeks on the Greek island of Corfu, two weeks at Meteora in Central Greece, three weeks in Cortina (Italy), and nine weeks at the Pinewood Studios near London, which included underwater filming in the Pinewood tank. An American underwater filming crew was concurrently shooting in the Bahamas.

With all of this lined out, I had to take stock of what my actual functions would be as director of photography and I sort of reckoned that, by order of priority, they would line up something like this:

- Be very close to, and loyal to, my director.

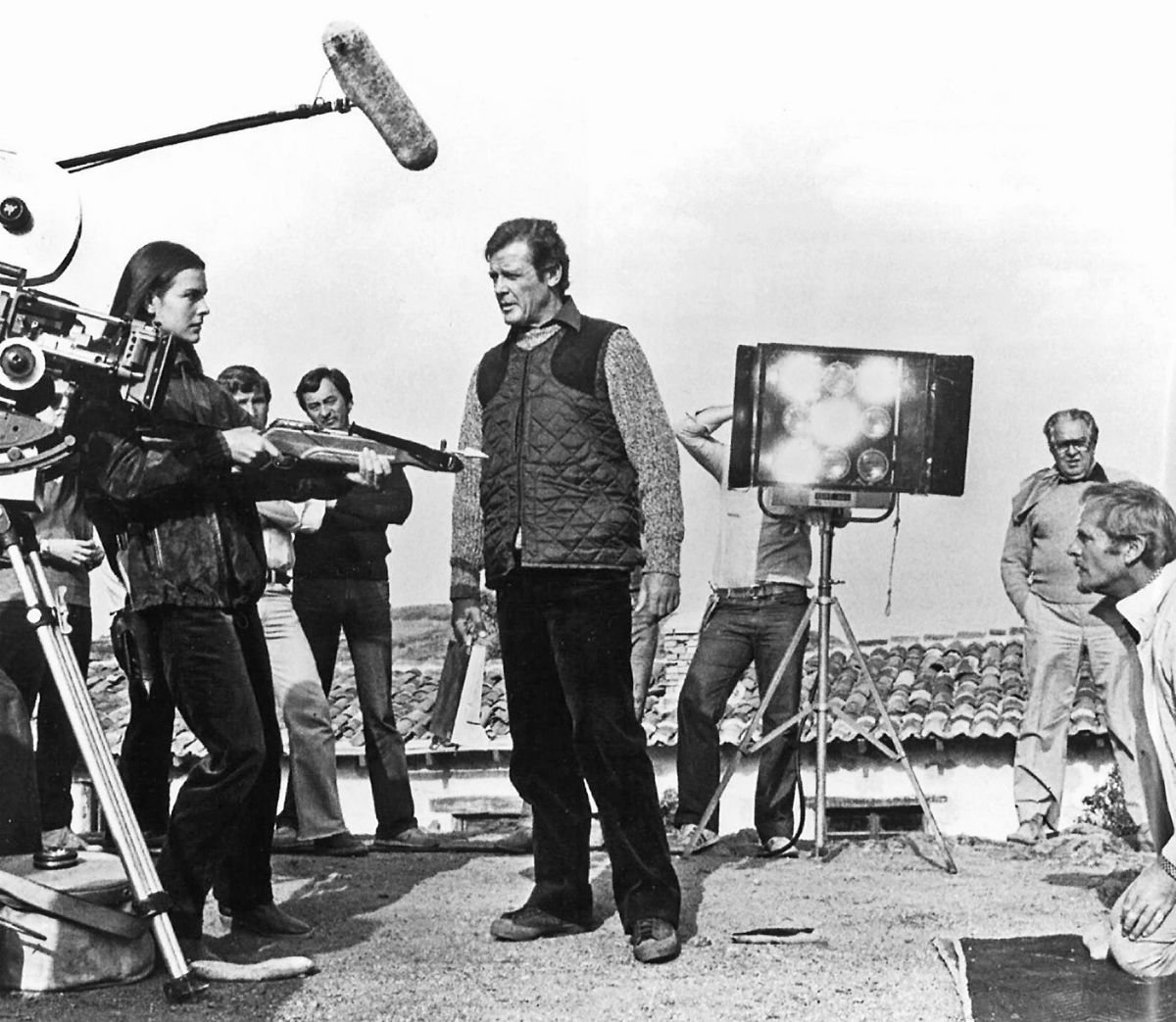

- Always try, my absolute darndest, to be sure that “James Bond” (Roger Moore) looked his immaculate, handsome self, no matter what the circumstances.

- Remember that James Bond pictures are always done with a very “glossy” see-it-all approach, yet with plenty of opportunity for the film to be visually interesting and moody when necessary.

- Be always aware that TIME IS MONEY and that TIME, TIDE, SUN AND RAIN, DAY AND NIGHT, WAIT FOR NO MAN....

- Always make time to listen to, and be helpful to, my fellow cameramen, on the other units... They have just as many problems as I have and, after all, I may even get the credit for some of their wonderful work.

My responsibility lay with the main unit, so I equipped myself to cope with all eventualities likely to occur (having, of course, read the script, but not, unfortunately, having seen the locations). During this preparation time, I was shooting another film, so location reconnaissance, from my angle, was taken care of by Arthur Wooster and my very good and experienced gaffer, John Tythe from Pinewood Studios.

The camera equipment selected was Panavision anamorphic, (supplied by Samuelson's of London). This was all put together by my wonderful assistant, Mike Frift; we have worked together for 12 years, and I have never known him to forget one nut or bolt, let alone a piece of necessary equipment. I stress the word necessary because I certainly don’t believe in carrying around, on expensive locations, unnecessary items. This can only lead to becoming inefficient. After all, equipment can be shipped in and out, of almost anywhere in Europe within 24 hours.

The complement of equipment which we carried with us included: a Golden Panaflex, a Panaflex-X, a hard-front Arri (72 fps) and, in the way of lenses, a 10-to-1 zoom, Panafocal and 20mm, 35mm, 40mm, 50mm, 75mm and 100mm. All of the lighting equipment was supplied by Roma Transporti and was put together by my gaffer, John Tythe, bearing in mind the requirements of both the first and second units. The gear proved to be first-class and the six Italian “sparks” working with us were excellent.

SHOOTING THE FILM

Every day was a different “ballgame” — always has been, always will be. After all, as I have already said, “Time, Tide, Sun and Rain, wait for no man,” and these days, producers and directors don’t seem to like waiting too long for the cameraman and crew, to sort out their problems. Fair enough, Time is Money... so we tried to anticipate every situation, run when needs be, work all reasonable and even unreasonable hours, and still come up smiling with material we could be proud of.

We had our problems. The film started shooting in September, so already the days were getting shorter, the sun lower, the rainy season nearer; nevertheless, we coped. John Glen was always willing to listen to everybody’s problems, and on occasions when I had to ask him “Can I shoot in this, or that direction first?” so as to take best advantage of light conditions, he would almost always agree.

Some of our locations were a little tricky to shoot. One example was shooting in Corfu Casino. It was a night sequence. The Casino interior was quite small, with low ceilings, so it was not possible to “rig” for lighting. All lamps were free-standing and the room was filled to overflowing with extras who had never worked in movies before. They would frequently stand right in front of the lamps, and even turn them around to avoid the glare in their eyes! When working under time pressures, such circumstances make the lighting cameraman’s job a wee bit frustrating.

On the same location, we were shooting exteriors on the Casino terrace, and of course, Sod’s Law being what it is, it chose to rain “cats and dogs” for at least half of the time, so we were forever dashing in and out of cover, re-setting the lamps and props, mopping up water and trying to hang up sheets of plastic to keep the rain off the actors. Oh, the frustration!

We had the same rain problems when shooting the dockside, smuggling and fight sequence — night exteriors, torrential, but intermittent rain — so we were just obliged to keep running for cover, every now and again. Then out we would come when it had stopped, clear up the mess, and start shooting again! This went on for about four nights. Fortunately, we had no problems with the electrical or camera equipment.

Peter Lamont, the production designer, built some super sets, both on location, and in the studio. When making his decisions on “sighting” the sets on location, he would always try to keep in mind and discuss with me, possible lighting problems, knowing that I would be involved infrequently having to match direct “cross-cuts” with studio and location sets, also I would be having to match the work of our other units when it came to shots of principal artists involved in sequences they had covered with “doubles.”

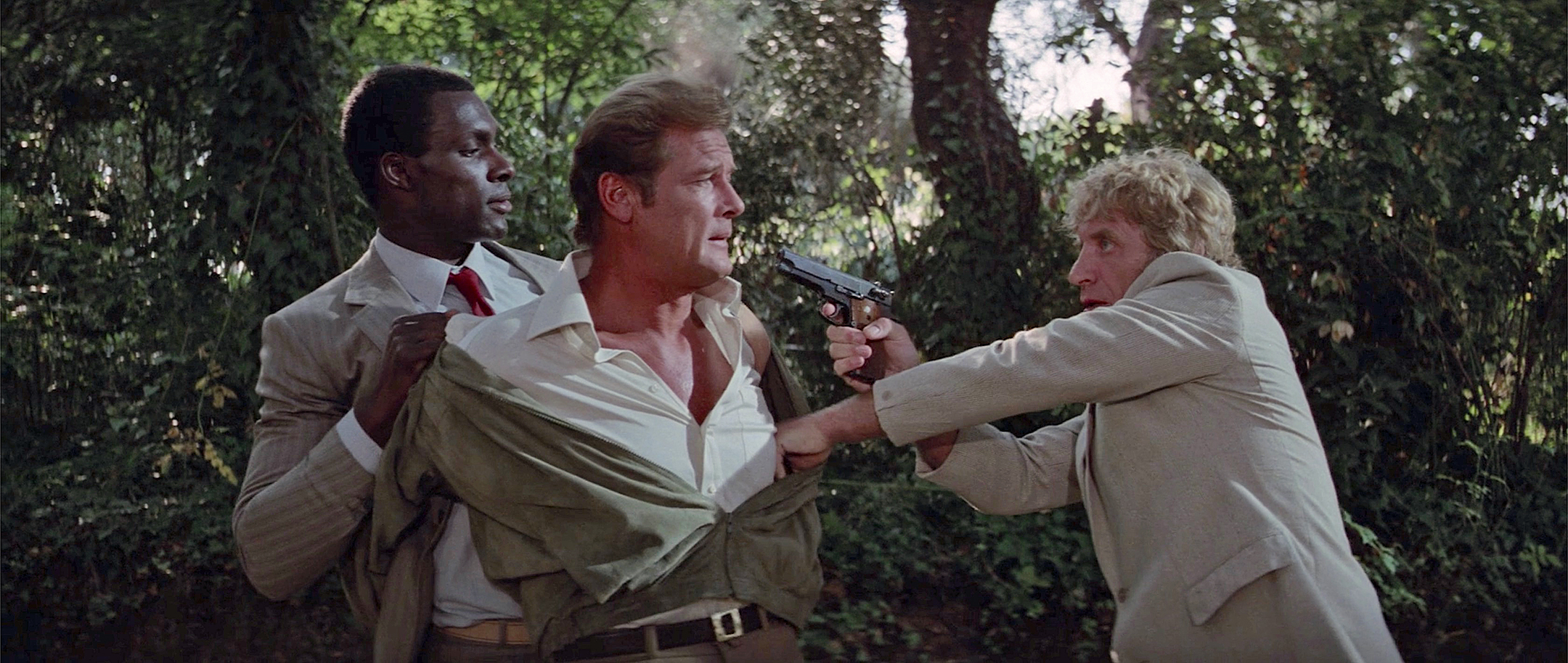

Quite a lot of front projection was involved in the filming, mainly to shoot close shots of Roger Moore and Carole Bouquet for the action sequences. These included a hectic car chase, highly dangerous ski and bobsled run material, as well as shots of Roger hanging onto the outside of the helicopter and eventually climbing into the cockpit to take control. All of the front projection was shot using Roy Moore’s setup, it being particularly small and maneuverable, with sophisticated light intensity and color control, yet capable of producing a picture 30 feet wide to a light level of T4. Front projection was preferred to traveling matte for what I consider to be obvious reasons.

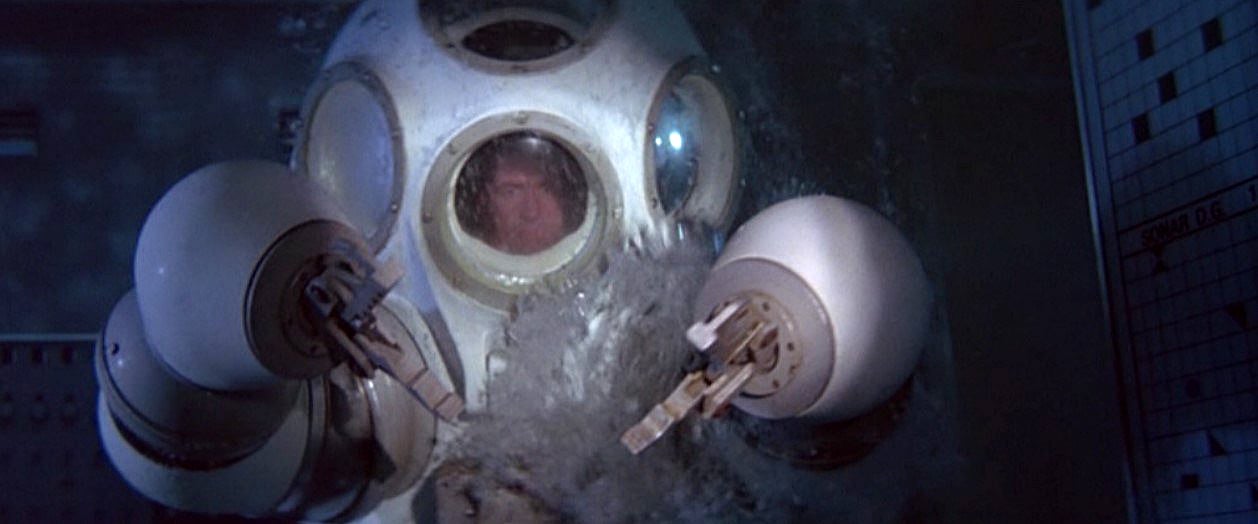

The film also has some very complicated underwater sequences. Obviously one cannot expect principal artists to work underwater, so the close shots of them, were done in the studio, on a nice dry, warm set. To get a realistic effect of hair movement, general slowness and weightlessness, which is so apparent in real underwater material, Derek Meddings shot some tests, running the camera at 120 fps and using strong wind machines to blow the hair upwards and from side to side. Also used were foreground glass fish tanks for bubble effects. Later, more bubbles were superimposed into critical areas of the picture. These tests were very promising and effective, so that was the way we photographed the underwater closeups of James Bond and his girl. Even if I say so myself, these shots proved so effective as to be undetectable from the real thing.

In general, my approach to the photography was very straightforward. I didn’t use anything unusual in the way of filters, just the usual 85 on exteriors and on most interiors a very light fog filter. Being on a Bond picture, I was in no way limited by a shortage of lighting equipment and on most exteriors, we carried four Brutes and six Mini-Brutes, plus all necessary bits and pieces. In the studio at Pinewood, there is never a shortage of lighting equipment, no matter what one requires. If one was to ask me what I found or find most difficult in my position as director of photography, I would say it is being able to visualize and see in my mind’s eye how I want the sequence to look. If it is an interior sequence then it is not so bad, as I can keep total control of the lighting and keep the visual look I have in mind — under control — with only the schedule to bug me!

If, on the other hand, it is exterior shooting, there can be a problem in pursuing a particular effect. In this picture, for example, we had a dawn sequence coming into early morning, then day. This sequence ran for three or four minutes and was scheduled for one day’s shooting — not a series of mornings and evenings — just one straight day, starting with first light and working through mid-day into late night. In order to meet this sort of challenge, it is necessary to try to persuade one’s director to make the shots for the sequence in the order most suitable to the director of photography, even though it might be very difficult continuity-wise. I always try to plan the day’s work so that the director is aware of my problems and, if I have played my cards right, I will usually find him willing to cooperate with me and the lighting conditions.

Through these pages I would like to thank Kodak for giving us such a superb negative to work with and also Technicolour for processing this negative and making the prints so expertly.

About the author: Alan Hume worked busily in films for nearly 50 years. Prior to this film, some of his credits included Gulliver's Travels, The Land That Time Forgot, Cleopatra Jones, and Bear Island. For Your Eyes Only was the first of his three Bond pictures, followed by Octopussy and A View to a Kill. His resume also includes such films as Supergirl, Runaway Train, LIfeforce and Star Wars: Episode VI — Return of the Jedi. He passed away in 2010 at the age of 85.

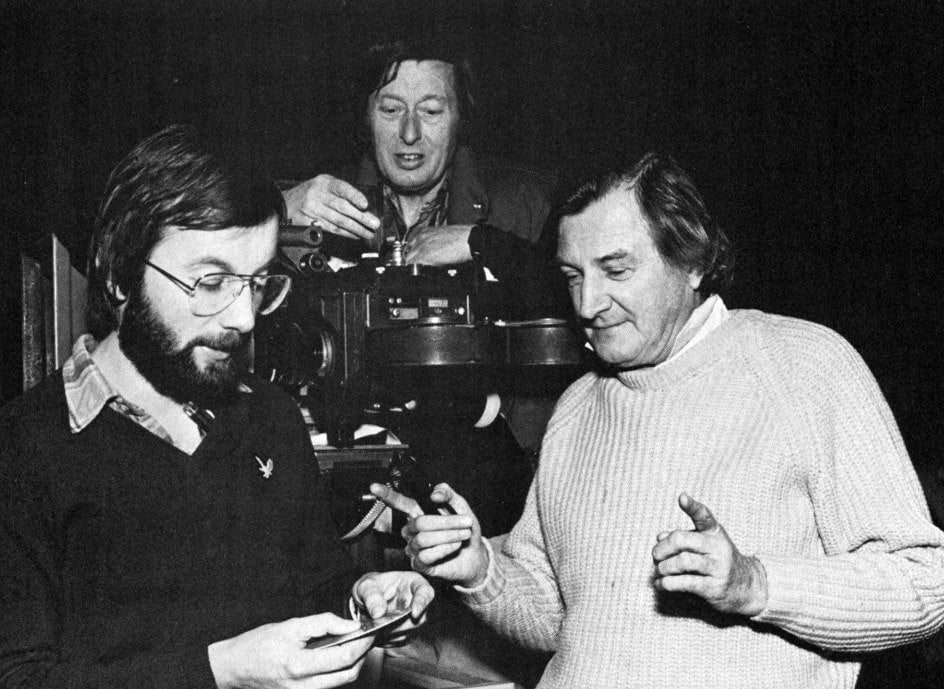

The Director Talks About For Your Eyes Only

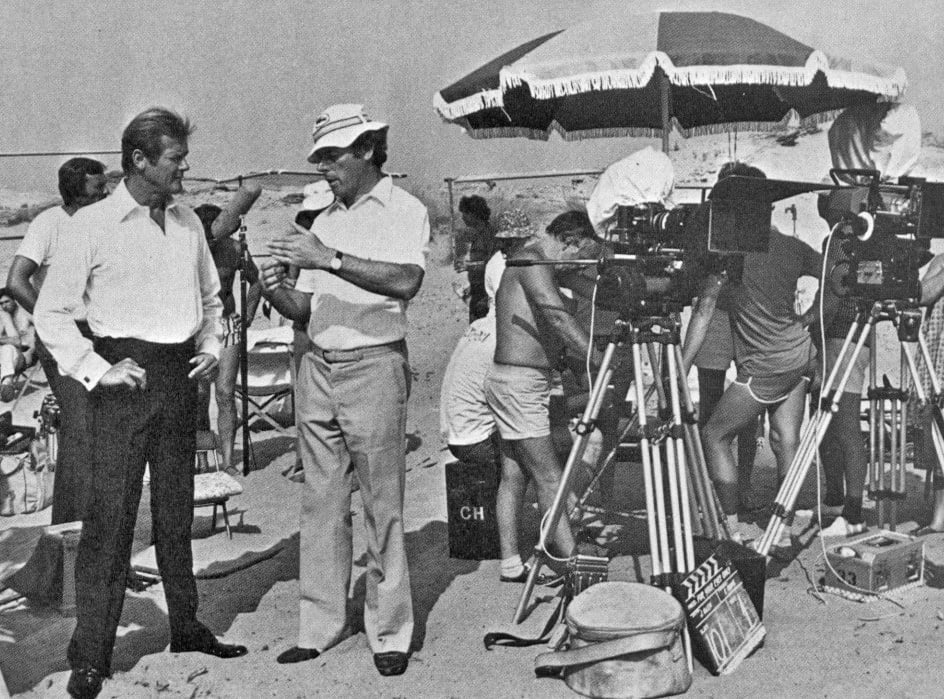

filming of an exciting dune buggy attack sequence.

The editor and second-unit director of four previous James Bond films scores a stunning feature directorial debut on this latest 007 thriller.

By John Glen

After recovering from the initial shock of being asked to direct For Your Eyes Only by James Bond producer Albert R. Broccoli, my thoughts turned to the crewing of this, the 12th in the most successful film series ever.

A natural to succeed Ken Adam as production designer was Peter Lamont, who had been connected with most previous Bonds, both as set dresser and art director. Derek Meddings was another key technician that we were fortunate enough to sign as director of special effects.

My first choice of photographer was Alan Hume, with whom I had worked previously on the highly successful ski parachute jump in The Spy Who Loved Me. Without Alan’s courage in placing the cameras on the precipice of Mount Asgard in Canada’s frozen north, the scene would never have been filmed. I shall never forget him disappearing over the edge and reappearing clutching an enormous rock that was suspended under the tripod to give it stability.

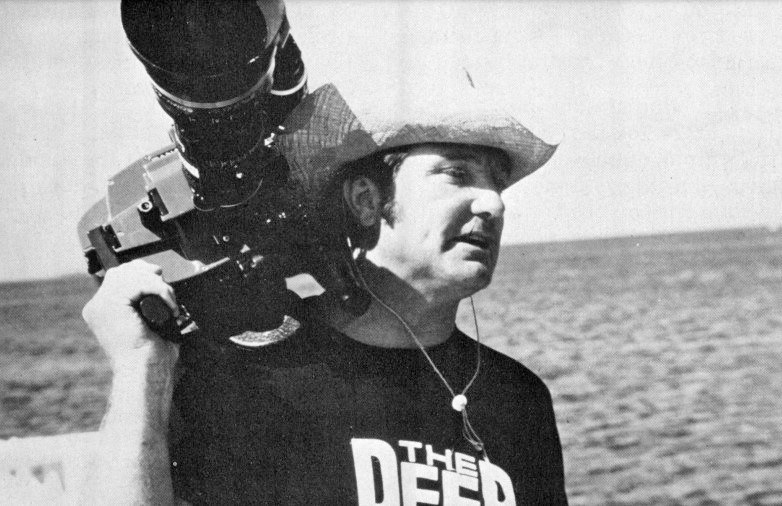

For the three major underwater sequences, Al Giddings, who had filmed underwater scenes for The Deep, was invited from Los Angeles to a conference at Pinewood Studios. Denis Rich, our storyboard artist, had been working on sketches of these scenes for some weeks, so we all planned together the breakdown of the segments to be shared between the four units that would be shooting at the same time in different places.

scenes which will intercut with the underwater footage for the sequence in which Bond and

Melina are “keelhauled” over sharp coral. The T-shirt is a souvenir from a previous assign¬

ment. (Photographs for this article by Walt Clayton/AI Giddings/Ocean Films, Ltd.)

It was divided as follows:

- First Unit: Greece with principal actors. (Surface)

- Underwater Unit: Bahamas. Al Giddings crew with doubles (Below Surface)

- 2nd Unit: Greece. Arthur Wooster and crew with doubles. (Surface)

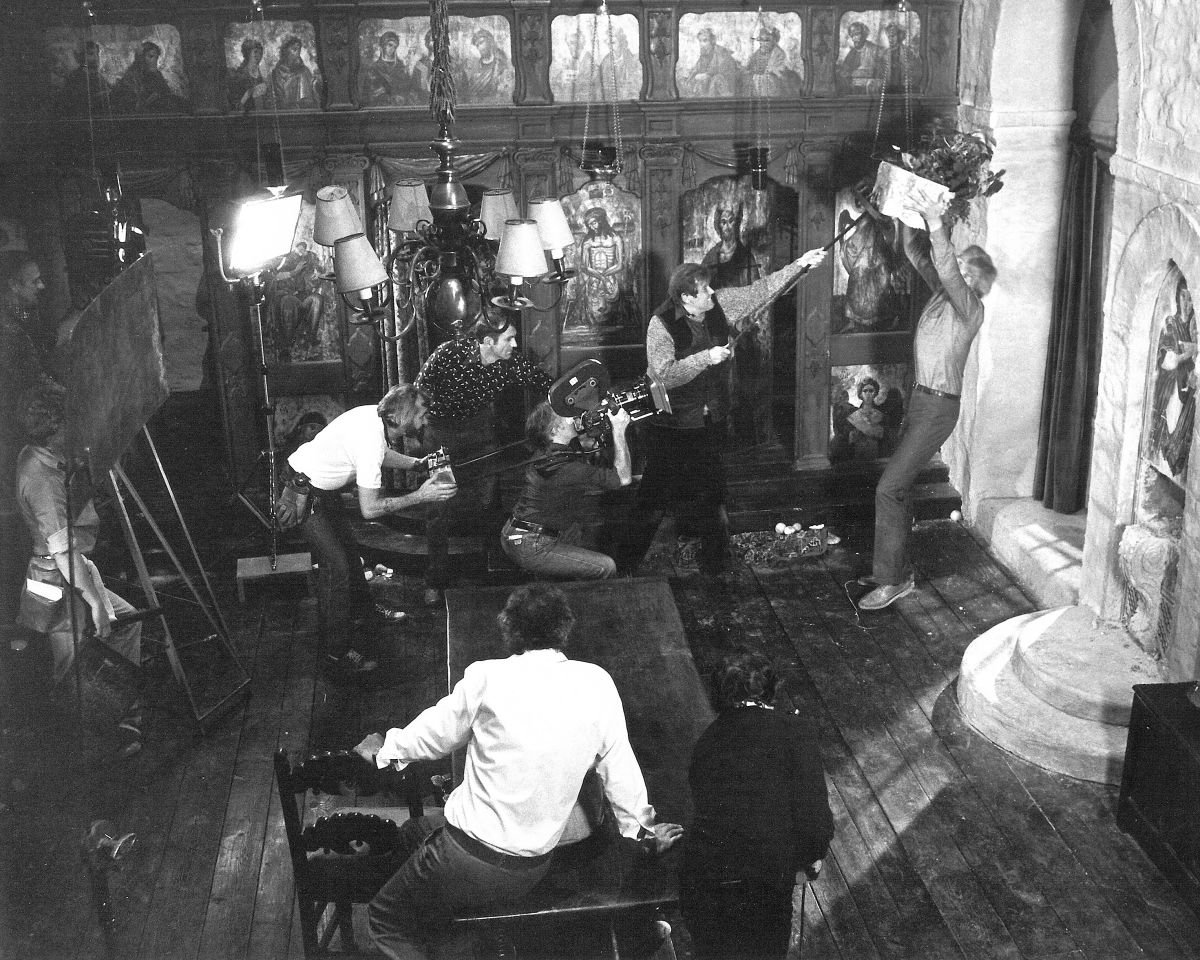

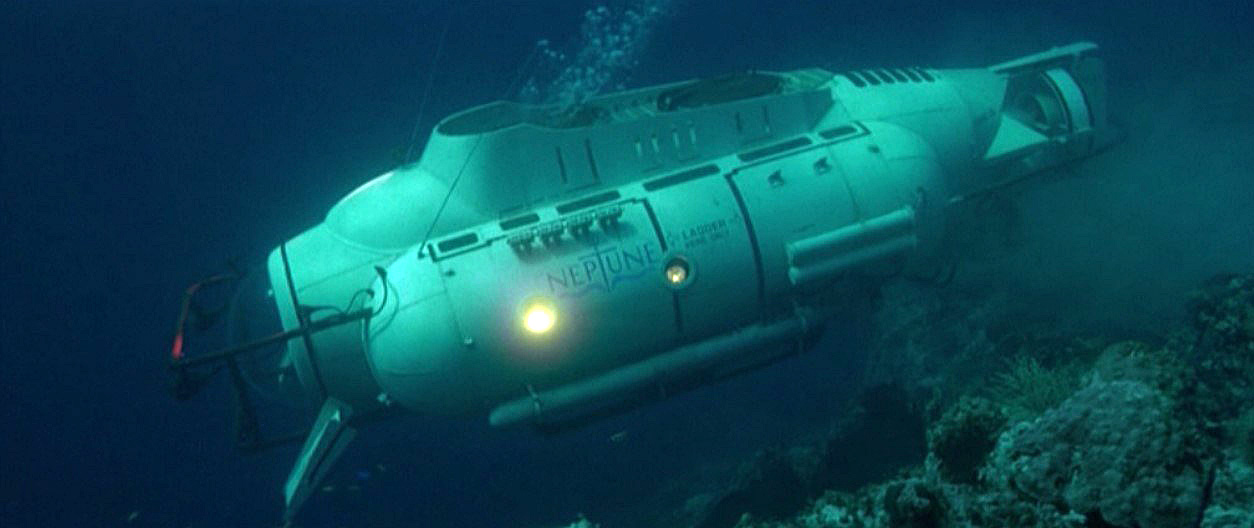

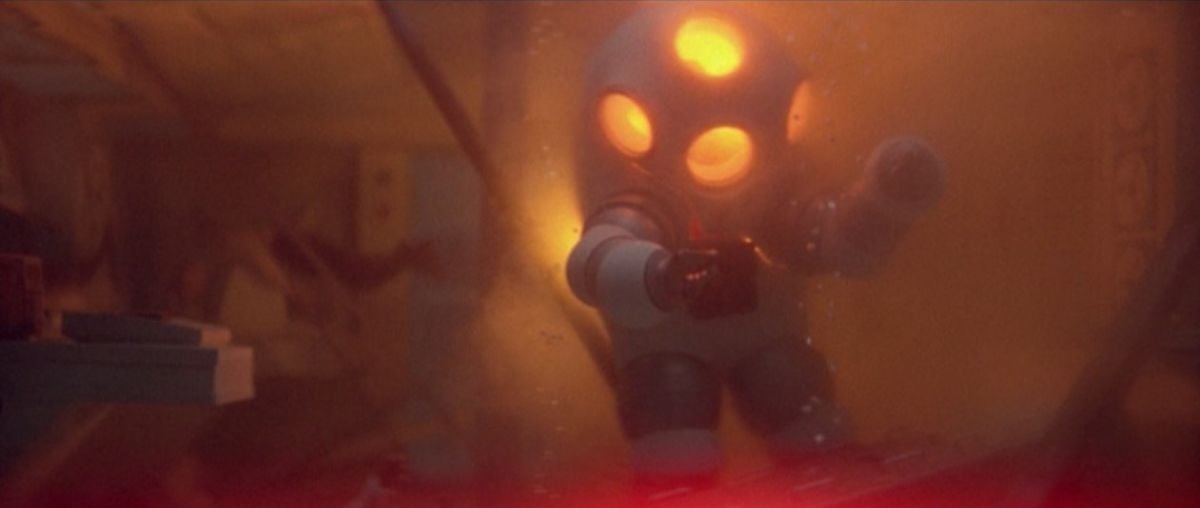

- Studio: Pinewood 007 Stage. Specially adapted tank with domed porthole. Peter Lamont designed this to enable the first unit to attach the interior submarine set externally to see into the tank with the Mantis submersible attacking Bond. By rocking the camera, light effects, C02, jets of water, sparks, and the actors throwing themselves about, a realistic effect was to be obtained.

The special effects team, with cameraman Paul Wilson and director Derek Meddings operating the underwater camera himself, would use the tank for model shots of the submarine approaching the sunken trawler. Secondly, the underwater explosion which rocks the trawler with Bond and Melina narrowly escaping the blast, then on to the Mantis fight which was to be part model and part full-size.

point of view. For other cuts in the keelhauling sequence he directed a powerful towboat

which dragged Bond and Melina just a few feet in front of his 50-500mm zoom. The

bright daylight available made it possible for him to maintain great depth of field.

Arthur Wooster was to follow into the tank to photograph the interior trawler for the sequence where Bond and Melina salvage the A.T.A.C. communicator device and are later attacked by J.I.M.!

The first unit was to shoot the trawler sinking, showing the death of the crew and the futile attempt to destroy the top-secret A.T.A.C. device.

The partially wrecked set was then to be craned out of Studio “C” and lowered into the 007 tank.

The close shots of the principal actors were to be shot “dry” by the first unit, using foreground and background fish tanks. Another technique used involved shooting a video positioning guide with Derek Meddings adding bubbles later, then processing the composite film in the usual way.

Peter Lamont was to design and plan the transportation of a submerged Greek temple for the Bahamas, and two full-size submarines with one practical, Derek Meddings having to duplicate these with models. The doubles, wardrobe and injury continuity was a major planning operation.

The camera operator is probably one of the most underrated technicians in our business. During the shooting, he is probably closer to the director than anyone. On this film, I was lucky in enticing Bond veteran Alec Mills to steer the camera. Alec had set his mind on making the leap to director of photography and it took the combined enthusiasm of Alan Hume and myself, over a pint of beer at the Black Horse pub to convince Alec of the fun he would be missing — and, after hearing most of the ideas for the film, he succumbed. [Mills would eventually take over the franchise DoP reigns starting with The Living Daylights]

One of the main problems we faced was lack of preparation time. At the beginning of June, we had a four-page story outline. The co-writers Richard Maibaum and Michael Wilson (also executive producer) were developing the script. Because of a combination of snow scenes and summer scenes in the story it was essential to start no later than September in Greece. I can remember the startling historic weather pattern for Corfu in September. It showed more rain than Manchester!

than anyone.”

One advantage of sandwiching location surveys with intervals of working closely on the script was the ability to adapt action scenes to fit the locations. Our surveys must have been the shortest on record. For instance, we completed the one in Corfu in two days, finding a dozen different sites. Michael Wilson drove the hired mini-bus and only succeeded in putting us in the ditch at the end of the second day.

The cameras first turned on a mini-location in the North Sea. We picked the best three days in living memory, with blue skies and calm sea. The scene was the sinking of a fishing trawler in the Ionian Sea. I visualized the scene starting underwater revealing the trawler as the camera rose to the surface. The box that the camera crew constructed to house the camera proved too heavy to launch and was soon abandoned in favor of a plastic bag!

Main shooting commenced in mid-September on the island of Corfu and the weather was superb for the first three weeks. Remy Julienne and his team of French stuntmen were hired for the car chase and later the ski/motorcycle chase, whilst Arthur Wooster and his second unit were enjoying themselves turning over cars.

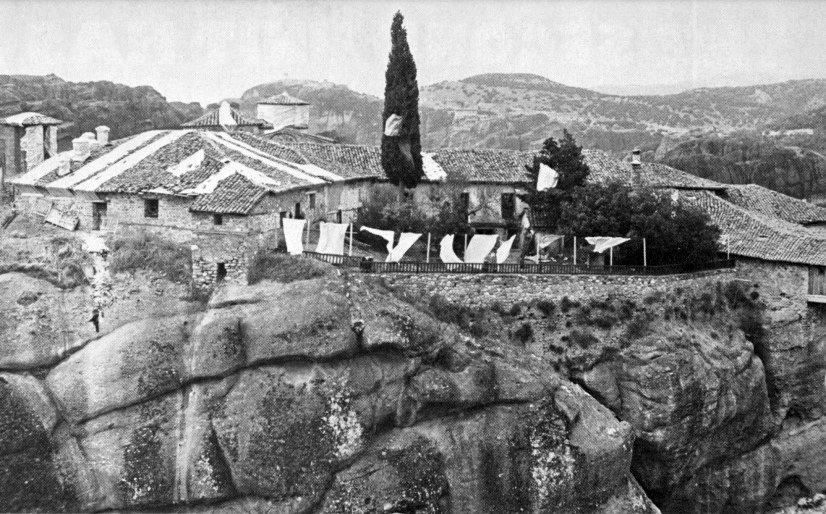

The first unit people were up to their necks in water, shooting the sea locations. Robin Brown photographed from the air. As we approached night work at the old fortress in Corfu Town, the skies opened and the rain continued until we left for the Meteora. The Meteora is a series of volcanic plugs shooting vertically upwards in central Greece. Perched on the peaks are almost thirty monasteries. For the film, we needed the co-operation of the local monks. Previously they had had a bad experience with a film company and were unwilling to cooperate with us. On the contrary, they went to endless trouble to frustrate us. They covered the principal monastery with plastic bunting and flags and placed oil drums to stop us landing by helicopter. However, they had not reckoned with our resourcefulness because, with the use of backlighting and the occasional matte, we completed our shooting. Peter Lamont built a section of the monastery on an adjoining rock which enabled us to film the helicopter landings and the death of the villain. The remainder was achieved by the construction of a beautiful monastery on one of the large stages at Pinewood Studios.

about 600 years ago, the Byzantine monks built their monasteries. Some of the monks

objected to the filming and draped their buildings with sheets to discourage the crew, as seen here.

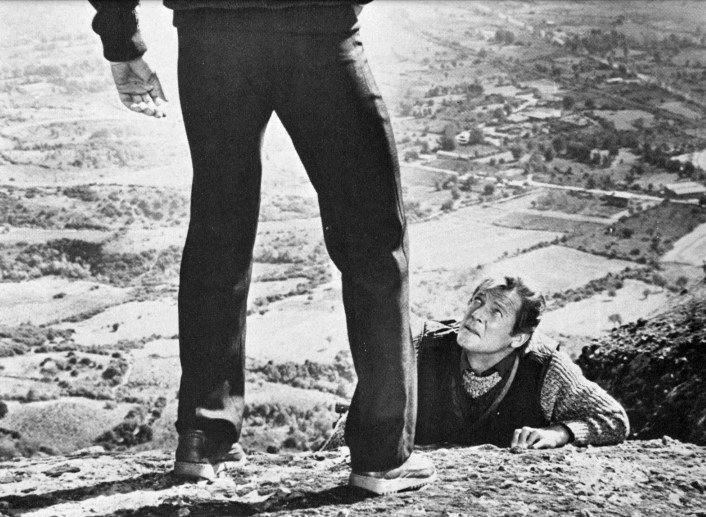

At this time it became obvious that Arthur Wooster’s second unit would be delayed in the Meteora by the foul weather and the monks’ inhospitality. The climbing scenes were becoming more difficult with the rain making the rocks slippery and dangerous.

Rick Sylvester, the ski/parachutist from The Spy Who Loved Me, was preparing for an especially exciting fall. It was decided that a further unit would have to be hired to shoot the pre-title sequence which consisted of a rather unusual helicopter flight. The choice of cameraman/director was made easy by the availability of James Devis who happened to have a three-week slot free. Jimmy and I had worked together on previous action scenes and we were able to communicate freely. Marc Wolff was to fly the helicopter with Albert Werry operating the aerial camera. Derek Meddings and Paul Wilson provided some excellent foreground miniature sets which defy detection.

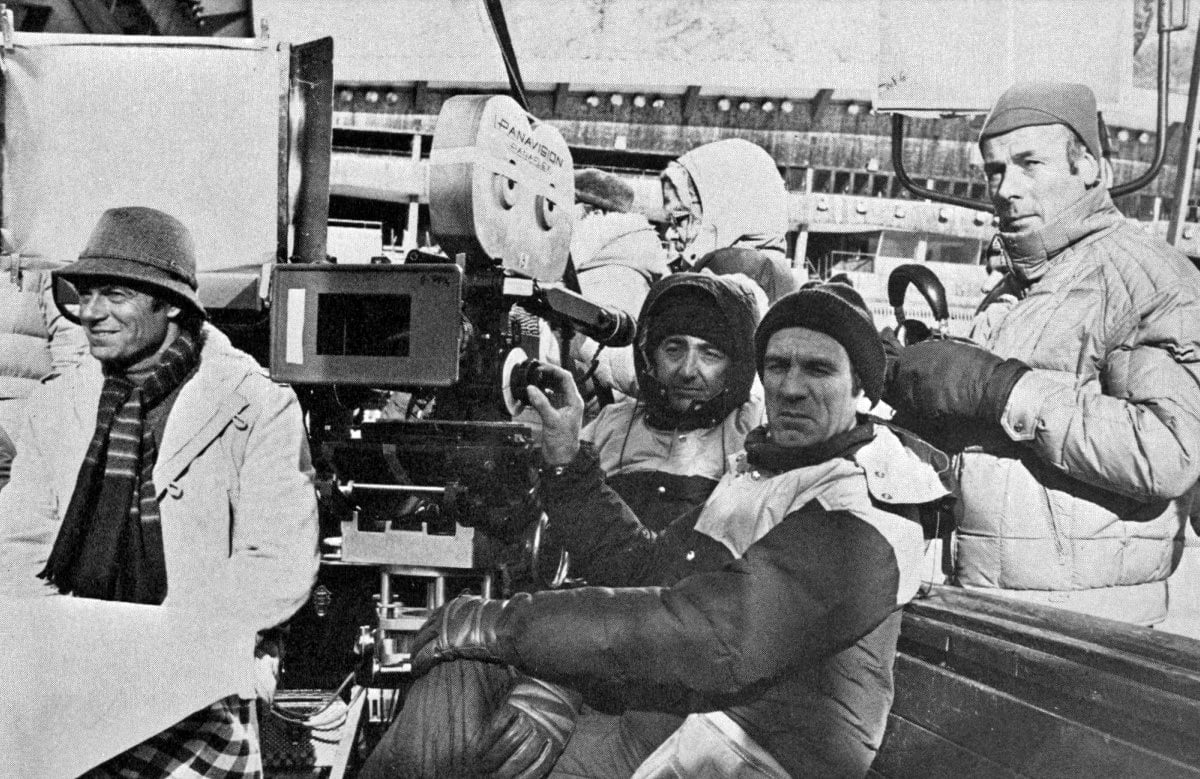

After a relatively comfortable period of studio work, we left for Cortina d’Ampezzo in the Italian Dolomites. Again we were blessed with good weather.

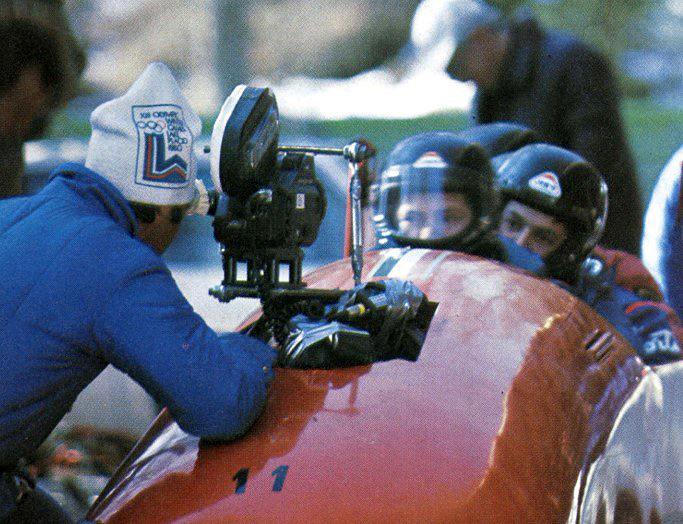

Willy Bogner, the skiing cameraman who had worked with me on On Her Majesty's Secret Service and The Spy Who Loved Me was appointed Ski Unit director/cameraman and, with the assistance of cameramen Peter Rohe and Gerhard Fromm, set about filming the ski chase scenes. The bobsled run presented problems inasmuch as the World Championships were about to take place and, understandably, the authorities frowned on motorcycles cutting up the run, so we had to delay that part of the filming until these events were completed. The daytime temperatures were sometimes as low as -18F. The actors' faces were frozen and playing scenes was not easy for them. The low temperature on the night shooting caused us some problems with definition. I am not sure that we ever found out the reason for the problem.

The locals were becoming increasingly concerned over the lack of snow. We were obliged to transport snow to dress our scenes but the hotels began to lose their real customers — the skiers.

About the author: Director John Glen is no stranger to the Bond saga, for he was editor and second unit director on On Her Majesty's Secret Service, The Spy Who Loved Me and Moonraker. For OHMSS, he directed several of the snow sequences, including the bobsled run and avalanche scenes. For Spy he was responsible for the memorable opening sequence showing the ski chase and the spectacular parachute. Following For Your Eyes Only, Glen would go on to direct four more Bond films; Octopussy, A View to a Kill, The Living Daylights and License to Kill.

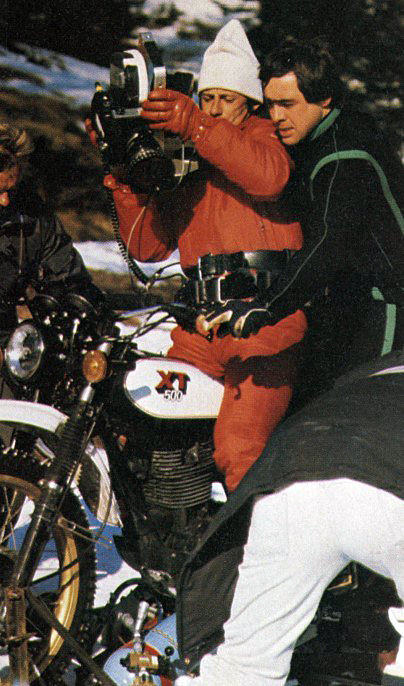

Bogner.

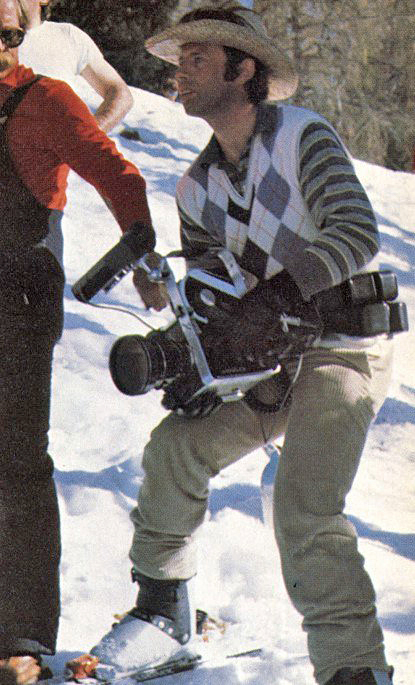

Olympic ski champion/cameraman pulls off some ice-borne aerobatics to capture some of the most exciting action in this 007 epic.

By Willy Bogner

I had done some filming on two previous James Bond pictures, as a special cameraman for the ski sequences of On Her Majesty's Secret Service, and also The Spy Who Loved Me. In this most recent film, For Your Eyes Only, I had the opportunity to both direct and photograph the ski sequences. I also had a chance to write some of the material myself, which was a very pleasant experience.

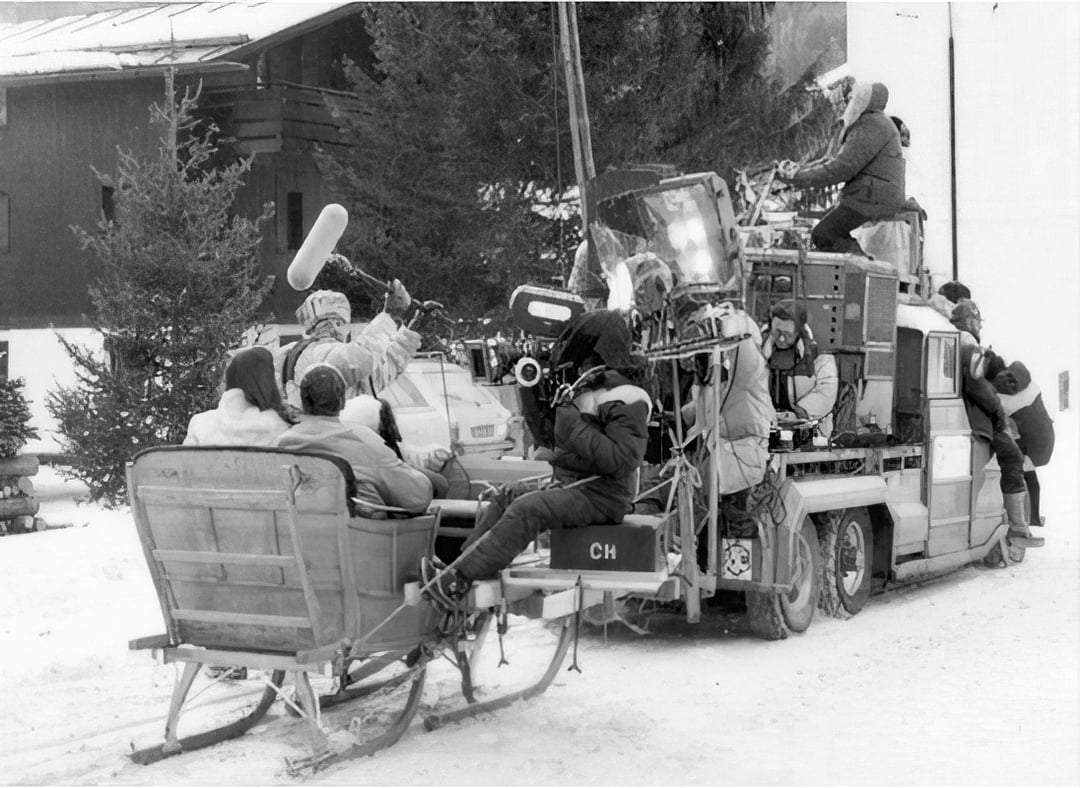

One of the most challenging sequences in this film was a chase involving a four-man bobsled, James Bond on skis and a motorbike pursuing Bond in the bob run at Cortina d’Ampezzo, Italy. The speeds of these chases varied between 35 and 55 miles per hour.

In order to get a very close look at the action and really capture the “feel” of this chase on film, I decided to do some tracking shots on skis in the bob run. I had already skied in a bob run for the previous Bond Film, On Her Majesty's Secret Service, and I knew that the technical aspects of skiing on ice were not too difficult for a good skier. My background as a former member of the German Olympic Ski Team helps me in realizing such shots, but then there were the technical problems of filming the sequence to be considered.

To solve the main problem, I rigged a handheld 35mm Arriflex-III camera with a video camera mounted on the side and a monitor on top. I could hand-hold it during the chase in the bobsled run and, because of the shock-absorbing effect of my knees and arms, it was possible to hold the camera really steady and get a perfectly clear picture, even at the very high speeds of the chase.

The Panavision lens used on the Arri-III was stripped of all unnecessary weight, but, still, with the video monitor mounted on top and two battery belts supplying the power for the Arri and, separately, for the TV unit, the total equipment weighed close to 65 pounds.

As protection against an eventual fall, I was wearing the protective gear of an ice hockey player that we rented in Cortina. Fortunately, I only fell once and, thanks to the protective gear, nothing happened to me or the equipment.

The way the action was planned, the bobsled would be in front, Bond just behind and, in the background, the motorcyclist. I was a little worried about whether the motorcyclist would be able to drive perfectly well on the banks of the bob run, but Remy Julienne, the famous French stunt coordinator for cars and motorbikes, was heading the stunt crew driving the bikes and he prepared the tires with special spikes and selected absolutely the right equipment. He assured me that they would be able to run at speeds up to 50 miles per hour in the bobsled run without major problems. Three young Frenchmen performed the stunts on the motorbikes: Jocote, Bernard Pasqual and Dominique Julienne.

In order to get one particular shot in the bobsled run it was necessary for me to hold the camera in one hand while, with the other hand, holding onto a wire connecting me with the sled. This was required because the sled, with its heavier weight, has a tendency to run away from the skier. In the run, I had to make sure that I kept the perfect distance for a close-up shot of the faces of the crew looking back at their pursuers. For another scene in the same sequence an even closer shot of the bob crew’s faces — I had to hold the camera in both hands, so I fastened the wire that connected me with the bobsled onto a belt, but in such a way that it could release very quickly.

One of the main problems of getting this shot was to select the right kind of wire — thin enough to not show in the picture, yet strong enough to pull the weight of the skier safely — but, after a few tests, we found the right combination and it worked. Of course, one couldn’t hold onto the bobsled for the entire length of the run, but it was enough for a few turns to get the shot I wanted.

For one series of cuts, it was necessary for me to shoot backward through the legs at Bond in a chase sequence around the turn in the bob run. The speed of this passage was approximately 45 miles per hour. For these shots I could mount the monitor of the camera in the rear, so that the center of balance would be right, and I could still have a clear picture of what was going on behind me. The Arri-III turned out to be perfectly balanced for this kind of shooting and we never had any functional problems with it. Also, the video equipment prepared for us by Samuelsons in London worked perfectly well after a few initial problems with the power source, which we overcame by adding a separate source for the TV equipment.

For a closeup in front of the bobsled crew we mounted the camera on a specially prepared sled. Being aware of the problems of extreme vibration in such filming, we constructed a very rigid mount for the Arri-III. When the bobsled arrived at the bottom after this run with the camera, most of the screws and bolts of the mount were shaken loose, but none of the functioning parts of the Arri-III, and we got very good results for our shot.

The script called for me to get a close shot of the motorbikes on a ski slope. This, of course, is more familiar terrain for a skier than for a motorbike and the main difficulty lay in coordinating the bikes with the right terrain. We were lucky because there was not too much snow in Cortina, so the bikes had firm ground to travel on.

on the clutch for the motorbike chase sequence.

The motorbikes had special cannons installed in their direction indicators that turned around mechanically and could fire a rocket at Bond. To photograph this special effect in action, I had to ski very close to the bikes, and the video monitor helped me to get the right framing during that shot.

The free, handheld configuration of the camera allowed me to be extremely flexible in the framing of my shots, especially inserts such as a closeup of the back wheel of the bike, a hand on the clutch, etc. To get the insert of the controls of the bike from above, we had a special bike constructed on a sled that was more easily controllable. Pressurized air drove the wheels of the bike and the sled was guided from behind.

During the chase, when Bond occasionally runs out of snow, his pursuers on the bikes come at him with their spikes dangerously exposed. To get the full impact of this attack we fixed the camera on the ground and the motorbikes ran right over it.

The high-point of the chase sequence is the scene when Bond takes off on a 90-meter ski jump, while a killer tries to knock him off the in-run. To get a safe and controlled shot of this fight on the jump tower, the whole top portion of the tower was reconstructed close to the ground and this enabled me to get an effective tracking shot.

For me it was a great experience working on For Your Eyes Only, especially since we were extremely lucky with the weather, having only two bad days out of seven weeks of shooting. With the great backing of a perfect organization on this Albert Broccoli production, I feel that we were able to film a quite unusual sequence.

In a paradox of filmmaking art, effects are often created on a small scale in order to make them larger than life on the screen.

By Paul Wilson, BSC

My first impression from reading the screenplay of For Your Eyes Only was that it would not present as much of a challenge as Moonraker. There seemed to be far more action centered around places and things that really existed and, therefore, not so much would have to be created on the effects stage.

Except for the sinking of the trawler, St. George, everything was for real, even the two-man sub and the Mantis. But I found that the challenges came about in different areas.

For a start, the trawler could not actually be sunk, even for a Bond film. We had to match the light and sea conditions on the exterior tank at Pinewood that a second unit had experienced in August with the real trawler in the North sea— and shoot in mid-November. No mean task in England that time of year when the sun is so low that there were only two hours in the middle of the day when the surrounding trees weren’t casting shadows on the backing.

Derek Meddings’ team of model makers had to make a good job of the St. George because after it was sunk in the exterior tank, it was raised and used in the 007 Stage, underwater, and shot on very closely.

The destruction of the paper warehouse was to have been shot on the Albanian location, (actually the Greek island of Corfu), but for some reason, this couldn’t happen. The whole harbor and surroundings had to be built in miniature and destroyed at Pinewood.

When a set is scaled down to one-fifth its size, the lamps used to light it should also be scaled down. Theoretically, this is possible. A 10K becomes a 2K, etc. However, to create scale and weight, the scene has to be shot at five times normal speed, especially when explosions are called for. The 10K that has become a 2K needs to remain that size, but have the intensity of a 10K. Any pool of light to be matched from the full-scale location has to be the scaled-down size but of five times the intensity.

To date, the most satisfactory lamps I have found for this purpose are the clip-on Jupiter Quartz units. They are of high intensity, compact and convenient for hiding behind miniature walls and buildings. I used 60 of these on one shot of the warehouse disintegration.

The opening helicopter sequence shot by Jimmy Devis needed our help. While Bond is fighting to gain control of the radio-controlled helicopter, it is seen to enter an abandoned warehouse, fly around and leave again. An elaborate rig was created by special effects for the actual flying inside the building, but the model unit had to show the real helicopter flying in one end of the warehouse and out the other.

Two foreground miniatures were created by the art department and carefully lined up with the real buildings. The helicopter, flying towards and down the side of the real building, appeared to be entering it because of the foreground.

I made it more convincing by pinning a piece of acrylic .6ND window filter at an angle to match the sun, across the fake entrance. The helicopter appeared to fly into a shadow.

The underwater miniature sequence had two main photographic problems, depth of field and the sense of being in very deep water. I overcame both problems with one stroke. I may be repeating Arthur Wooster, but at that depth, there is no light by which to photograph. All you would really see would be the light from the spotlights on the underwater craft. For lack of a better phrase, cinematic license had to be taken. I decided to treat it as day-for-night and underexpose by two stops. Arthur Wooster had been using a rig of sixty 10K lamps supplemented by rows of Malham trough lamps.

When photographing the live-action, full-scale Mantis, and two-man sub, he had used full-blue correction to get the color he was after. The cost-conscious production department asked me if I could use the same rig, and were delighted when I said yes.

Arthur was shooting between T2 and T2.8. I needed at least T4 to get the depth of field required when shooting close to a model. I had all the blue filters removed from the lamps and replaced those at the extremities of the tank with half-blue. By having Technicolor print blue to match Arthur’s material, I was able to get that deep blue in the background that indicated an infinity of water.

The practicals on the Mantis and mini-sub I overran and warmed up with 1/2 CTO filters, bringing them close to Arthur’s. Maybe not as bright, but as we were not close, the match seemed good.

All in all, I would say that I had more problems on For Your Eyes Only than on Moonraker, because I had to match to full-scale, live-action film already shot. What I shot had to be cut into those sequences without being noticed. When no one notices a visual effects cinematographer’s work, he has achieved what he set out to do — fool ’em!

Some of the most spectacular flying and adroit camerawork ever seen on-screen start this James Bond film off with a resounding bang.

By Jimmy Devis

On returning from photographing a film in the USA, I received a telephone call from the James Bond office, telling me that John Glen would like me to direct the For Your Eyes Only opening sequence for him. I had the year before directed the battle scenes on Inchon for Terence Young, one of the earlier Bond directors.

As is usual on all Bond films, to make the unbelievable look believable was a challenge. I set off with the location manager to recce the place chosen by John Glen and the director of photography, Alan Hume, with production designer Peter Lamont, before they left for Corfu.

We arrived at Becton Gas Works, which is situated on the banks of the River Thames in East London. There I met the helicopter pilot, Marc Wolff, and Al Werry, who was the aerial cameraman. They have worked on many films and commercials together and have a unique understanding of each other’s job.

All four of us walked over the course I wanted them to fly and was guided by Marc Wolff on the possibility of flying under and over superstructures, turning on a pin-point, or diving through into buildings. We were using a Bell JetRanger for Bond’s helicopter, and for the camera platform, an Alouette fitted with a Helimount. This could be fitted on either side or anywhere on the skids. Marc and Al had also given me mounts underneath, and a chair on which Al Werry could sit outside of the helicopter. It took some expert flying, with all the drag on one side.

We took about three weeks in all to shoot the sequence, after the first unit and the model unit left. Derek Meddings was in charge of building and shooting the foreground models. Also, he built the mock helicopter inside one of the large derelict buildings on approximately 1,000' of rails, powered by a small engine. He was able to simulate the flying by moving the helicopter up and down and to either side by means of a hydraulic system which he controlled himself.

I had two cameras on the ground and an Arriflex with a 10-to-1 zoom on the Alouette. The first weekend I shot all the front-projection plates so that John Glen and Alan Hume could have time to choose the plates and shoot the closeups on Bond in the studio in case we were held up by bad weather. As it happened, we were extremely lucky and had 75% good weather. Sometimes the wind was too strong and we could not fly, so we shot inserts on the mock helicopter.

As I was shooting in November and early December, the sun was very low and the days were very short. We could only shoot between 8:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m., sometimes 4:30 p.m. when there were no clouds at all, but the sun was very yellow and the shadows very long. There was one particular place where I could only shoot when the sun was at its highest, so each day we had to go back and shoot a piece more.

When Bond gains control of the helicopter by climbing out of the back, and along the skids to the front, he pushes the pilot out (who is dead) and lets him fall from 200'. We did this by rigging dual controls in the helicopter, with Marc Wolff flying it from the left side and a dummy in the pilot’s seat. I covered this with the two cameras and the flying camera, keeping the flying camera well out of the way of the two on the ground by using the long end of the zoom on the helicopter.

The next thing we shot was the wheelchair, which the villain is sitting in, on top of a roof, while flying the helicopter by remote control. John Glen had a good idea of picking up the chair on the end of Bond’s helicopter’s skid and dropping the villain down an unused 300' chimney. Marc Wolff again came to my aid. With his mechanic, they built a special rig, with a bomb-release button inside the helicopter. Marc Wolff did three runs and each time he was spot-on and dropped the wheelchair straight into the chimney. Al Werry shot from the Alouette, tracking and zooming, and eventually by flying the helicopter almost on its side, was able to get right over the top and zoom straight down into the darkness of the chimney, which we used with good sound effects.

We had no trouble with any of the Pan-Arris supplied by Samuelsons whilst flying, even in the very cold winds and early morning frosts.

Martin Grace, Bond’s stunt double, did a fantastic job for me by hanging from underneath the helicopter 500' up, and we were able to shoot on him from all angles on both helicopters because of the interchangeable mounts, made by Marc Wolff’s engineer.

As a cameraman, I found this to be a very enjoyable experience and sincerely wish John Glen and all those involved in the making of For Your Eyes Only great success with the picture.